Abstract

The professional efficacy and health perceptions of physical education (PE) teachers, along with school characteristics, significantly impact their ability to navigate remote teaching challenges, maintain student engagement, and deliver inclusive, effective instruction. Remote teaching has become a widespread instructional method, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, but it also presents unique challenges for PE educators, requiring specialized pedagogical strategies and technological adaptation. This study aims to evaluate the professional efficacy, health perceptions, and pedagogical approaches of PE teachers in the context of remote teaching. Employing an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design, we conducted a cross-sectional web survey (N = 757) followed by in-depth interviews (N = 15). Participants were selected from a list provided by the Israeli Ministry of Education, with inclusion criteria requiring at least one year of PE teaching experience. Quantitative data analysis included chi-square tests, t-tests, Pearson correlation, and multiple regression analyses, while qualitative data were analyzed using conventional content analysis to identify emergent themes. Our analysis reveals that female with higher levels of education, research skills, and advanced knowledge in teaching technologies exhibit significantly greater teaching professional efficacy in remote settings. These findings suggest that educational institutions should develop tailored training programs that account for gender and educational differences, thereby equipping PE teachers with the necessary skills to excel in remote teaching environments. This proactive approach will better prepare PE educators to navigate future challenges in the ever-evolving landscape of education.

1. Introduction

Remote teaching has become a widely adopted mode of instruction, particularly in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Heng & Sol, 2021; Glaser et al., 2022). However, beyond medical emergencies, various other circumstances can necessitate school closures, including natural disasters (e.g., severe weather, fires), technological crises (e.g., hazardous material accidents), and human-made emergencies (e.g., wars, active shooter situations). Against this backdrop, it is critical to examine the factors that influence the effectiveness of remote teaching, especially for physical education (PE) teachers (Mercier et al., 2021). Remote teaching—often called online learning—presents educators with unique opportunities and distinct challenges (Leech et al., 2020). It enables students to engage in learning activities without being physically present, facilitates self-paced learning, and leverages digital resources to accommodate diverse learning styles. However, delivering PE remotely requires specialized skills, strategies, and support systems (Mercier et al., 2021). PE teachers face particular challenges when teaching in an online setting. These include difficulties with curriculum planning, assessing student performance, ensuring accountability, and maintaining safety—all of which can significantly impact the quality of remote PE instruction and learning outcomes (Gobbi et al., 2021; Giladi et al., 2021).

Among the factors that influence PE teachers’ remote teaching ability is their self-efficacy. Self-efficacy and work engagement were relevant to mastering the challenges of PE teaching during the pandemic and beyond (Gobbi et al., 2021). Bandura (1986) defined self-efficacy as “a person’s judgment of his or her abilities to organize and execute courses of action necessary to achieve designated types of performances” (Giladi et al., 2021). Teacher self-efficacy is the belief in one’s ability to teach and engage students in a learning environment effectively. Teachers with a strong belief in their teaching capabilities will achieve higher goals. In contrast, those with a weak belief in their capabilities grapple with a fear of failure (Hussain et al., 2022). Educators with high levels of self-efficacy are more likely to accept challenges and implement effective teaching strategies while those with low levels of self-efficacy are more likely to feel ineffective and dissatisfied with online learning (Fauzi & Sastra Khusuma, 2020). Professional efficacy, which encompasses the confidence and competence of PE teachers in delivering quality PE lessons through online platforms, has a crucial role in the effectiveness of remote teaching practices and student learning outcomes (Cardullo et al., 2021).

The integration of technology into physical education brings both opportunities and challenges and requires educators to adapt their pedagogical approaches and embrace new digital tools (Wallace et al., 2022). The rise in online physical education has been further accelerated by recent global events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which necessitated the rapid transition to remote learning environments (Chiu et al., 2021). During this time, many teachers have experienced both difficulties and successes, highlighting the importance of understanding these experiences to improve the online implementation of physical education programs (Daw-as & Magat, 2022). The sudden shift to online learning has forced teachers to re-evaluate their teaching methods and adapt to the unique demands of the digital world (Sato et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2025).

One of the biggest challenges in online physical education is maintaining student engagement and motivation (Mohnsen, 2012). To promote meaningful engagement in online environments, teachers must utilize various strategies and instructional practices that encourage active participation and collaboration (McKeithan et al., 2021). The success of online physical education depends on teachers’ ability to use technology effectively to deliver engaging and interactive learning experiences. Physical education teachers need to improve their digital teaching skills. This includes technical knowledge, a deep understanding of the pedagogical potential of digital tools, and the ability to analyze and respond to student feedback (Zhang et al., 2025). Establishing clear communication channels and providing timely feedback are essential components for fostering connection and support in virtual learning environments (Sato et al., 2023). To improve their effectiveness in distance teaching, PE teachers should actively work with available technological resources and acquire skills in using digital platforms that support communication, collaboration, and assessment processes. The integration of information and communication technologies (ICTs) into teaching practice requires that teachers are provided with meaningful opportunities for professional development in digital pedagogy (Rakisheva & Witt, 2022). With the increasing prevalence of virtual learning environments, students are demonstrating higher levels of engagement and immersion in relevant online learning experiences (Dang et al., 2024).

Health perception is another key factor which affects PE teachers’ job performance; PE teachers’ health perceptions also have a significant role in their ability to effectively perform their job duties (Bartholomew et al., 2014). Teacher health and well-being are vital to creating a conducive learning environment and positively impacting student experiences (Benevene et al., 2020). Health perception refers to how teachers subjectively evaluate their overall health status and encompasses physical, mental, and emotional well-being (Ben Amotz et al., 2022). The health and well-being of teachers, in general and especially during emergencies, play a crucial role in their job performance (Centeio et al., 2021; Whalen, 2020). Teachers who experience high levels of stress or face physical or mental health challenges may develop a negative perception of their health. This negative health perception can harm their ability to carry out their teaching responsibilities effectively. Conversely, when teachers perceive themselves as healthy, they are more likely to possess high levels of self-efficacy and be more energetic, engaged, and effective while teaching (Lee et al., 2024; Su et al., 2022).

In addition to teachers’ professional efficacy and health perception, various school characteristics can influence the effectiveness of remote teaching among PE teachers (Jeong & So, 2020). Factors such as the type of school, teaching experience, and school management practices can significantly impact teachers’ confidence and competence in delivering remote PE lessons (Hussain et al., 2022). Demographic parameters, such as gender and education level, can also have implications for teachers in the remote teaching of PE (Bortoleto et al., 2020). Creating an inclusive and supportive environment in remote teaching is essential, as PE teachers consider their students’ diverse needs, interests, and preferences, and tailor activities, learning objectives, feedback, and assessment methods accordingly (Monteiro et al., 2021).

In line with the above, using a mixed-methods approach, the current study aimed to evaluate the professional efficacy, health perceptions, and pedagogical approaches of PE teachers in the context of remote teaching.

This study aimed to evaluate the professional efficacy, health perceptions, and pedagogical approaches of physical education (PE) teachers in the context of remote teaching, by addressing the following research questions: (1) What are the levels of remote teaching professional efficacy and health perception among PE teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic? (2) Are there significant differences in professional efficacy based on teachers’ demographic, educational, and school characteristics? (3) What is the relationship between PE teachers’ health perceptions and their professional efficacy in remote teaching? (4) What factors predict higher levels of professional efficacy in remote instruction? (5) How do PE teachers describe their experiences, challenges, and successes with remote teaching?

2. Materials and Methods

This section describes the methodological framework of this study, including the research design, participant selection, data collection procedures, and ethical considerations. We used a mixed-methods approach combining a quantitative cross-sectional survey with qualitative interviews to gain a comprehensive understanding of PE teachers’ experiences of distance education.

The data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, ensuring relevance to real-world pedagogical challenges. This study adhered to strict ethical standards, including informed consent and anonymity, to ensure the integrity and reliability of the results.

2.1. Study Design

We employed an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design, consisting of a quantitative cross-sectional survey followed by in-depth qualitative interviews. This design allowed for a comprehensive exploration of physical education teachers’ experiences with remote teaching, combining the strengths of both quantitative and qualitative approaches. The research design and data collection procedures adhered to high reporting standards for mixed-methods studies (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2017; O’Cathain et al., 2008).

2.2. Participants and Procedure

Data were collected in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, when school teaching was conducted remotely. A survey questionnaire measuring professional efficacy was distributed to potential participants. We employed a convenience sampling approach using a list of physical education (PE) teachers provided by the Israeli Ministry of Education.

The sampling frame consisted of 800 PE teachers randomly selected from regular and special education schools across Israel. Inclusion criteria required participants to have at least one year of PE teaching experience and to provide informed consent. The exclusion criterion was PE teachers with less than one year of teaching experience.

The final study population comprised 757 PE teachers, of whom 65.7% were female. The mean age was 46.96 ± 10.20 years, with an average of 17.37 ± 11.09 years of teaching experience. The majority taught at the elementary school level (n = 392, 51.5%), and the most common school type was the general (secular Jewish) public school system (n = 537, 70.5%).

A letter was sent to the selected teachers, explaining this study’s objectives and the significance of their participation. The participating teachers completed online questionnaires between May and June 2020, and responses were collected anonymously by the lead researcher.

We then approached 30 physical education (PE) educators from our sampling frame within the Ministry of Education, of whom 15 agreed to participate in a qualitative interview. Two college students from the university’s Department of Social Sciences served as research assistants and conducted semi-structured interviews with the 15 PE teachers via the Zoom platform.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: Minimum teaching experience: participants had to have at least one year of experience in teaching physical education. Selection process: The Israeli Ministry of Education provided a list of eligible physical education teachers and 30 teachers were initially contacted. Of these, 15 agreed to participate. Consideration of diversity: Care was taken to ensure that the participants were as diverse as possible in terms of gender, school type (public, religious, special school), and grade level (elementary, middle school, and high school). Experience with distance learning: Participants had experience with distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, ensuring relevant insights into the focus of this study.

Before the interviews, participants were explicitly informed that any information they considered confidential would not be documented or recorded. Additionally, they were given the option to decline answering any questions that made them uncomfortable. The audio recordings of the interviews were subsequently transcribed to facilitate data analysis.

This study received approval from the Ariel University Institutional Review Board (IRB) to ensure compliance with ethical guidelines. Participants were provided with comprehensive information about the research objectives and voluntarily agreed to participate.

Before completing the survey, participants signed an informed consent form, confirming their voluntary participation. They were assured of their right to withdraw from this study at any time, that their responses would remain confidential, and that the survey data would be analyzed anonymously.

2.3. Independent Variables

Socio-demographic variables included sex (female, male), age, family status (single, in a relationship, divorced, widowed), religion (Jewish, Muslim, Christian, Druze, other), level of religiosity (secular, traditional, religious; measured by self-definition), education level (senior teacher, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, doctoral degree), and years of seniority at the school.

Teaching-related variables included the religious sector affiliation of the public school, as designated by the Ministry of Education (secular Jewish, Orthodox Jewish, Arab, Druze), and school type (elementary, middle, high school).

The policy regarding remote teaching was assessed using items from the European Federation of Adapted Physical Activity (EUFAPA) survey. One item stated: “In my workplace, there are clear guidelines regarding the usage of remote teaching and remote communication”. Responses were recorded on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Remote teaching media usage was also measured using items from the EUFAPA survey. Sample questions included: “What media do you use daily to communicate with students and colleagues?” and “What media do you use for remote teaching in PE lessons?” In the current study, the internal reliability of the scale was determined to be good, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.85.

2.4. Dependent Variables

Health perception—Participants’ health was self-rated in response to the following question: “How would you describe your health during the past year?” Answers were scored on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (poor) to 6 (excellent). The self-rated scale is a standardized indicator widely used in diverse health research studies (Wu et al., 2021).

Professional efficacy—The questionnaire consists of 11 items (for example: “I must succeed in conveying content in physical education via distance learning”) on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”. Higher scores indicate greater self-efficacy in distance learning. The scores were used as both continuous and categorical variables (those with a score below and above the median score of 39). In addition, participants who scored 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 3 (“average”) were categorized as having low to average professional efficacy, while those who scored 4 (“agree”) and 5 (“strongly agree”) were categorized as having high professional efficacy. The questionnaire has been validated in several studies and has both content and predictive validity (Chen et al., 2001). In the present study, the scale demonstrated good internal reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.83.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

In the quantitative section of this study, statistical analyses were performed using two software programs. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for Cronbach’s alpha calculations, descriptive statistics, chi-square (χ2) tests, independent t-tests, and Pearson correlation analyses. MedCalc statistical software was employed for multiple regression analysis.

2.5.1. Study Participants’, Demographic, Teaching, and School Characteristics

Demographic, teaching, and school characteristics were described using descriptive statistics (n, percentage, mean, and standard deviations). Differences in prevalence of the categorical variables were examined using chi-squared tests.

2.5.2. Teachers’ Remote Teaching Professional Efficacy and Health Perception Differences

The prevalence of teachers with poor-to-average professional efficacy and high efficacy on each of the scale’s 11 items was calculated and compared using chi-square tests. In addition, the association between professional efficacy and health perception was examined using Pearson’s correlation. In the next step, differences in remote teaching professional efficacy between participants with different perceptions of their own health status were compared using One-Way Analysis of Variance with Tukey–Kramer post hoc tests. These results are also presented using a box-plot figure.

2.5.3. Factors Influencing Variations Between Participants with Different Levels of Remote Teaching Professional Efficacy

The Pearson correlation coefficient examined the associations between participants’ professional efficacy and continuous variables (age and seniority). The mean scores of the professional efficacy of participants with different characteristics were then compared using a t-test (dichotomous categorical outcomes) or One-Way Analysis of Variance (three- and four-level categorical outcomes). In the One-Way Analysis of Variance, the Tukey–Kramer post hoc test was used.

2.5.4. Factors Predicting Remote Teaching Professional Efficacy

A multiple binary logistic regression was performed to determine how basic demographic, teaching, and school characteristics can predict binary categorical variables, namely, presenting below- or above-median professional efficacy. In this respect, the dependent variables were coded as 0 (i.e., presenting below-median professional efficacy) and 1 (i.e., presenting above-median professional efficacy). For continuous variables, only variables whose correlation with teachers’ professional efficacy were statistically significant were entered into the model. Similarly, for categorical variables, only variables whose statistically significant ability to differentiate between participants with different levels of professional efficacy were entered into the model.

2.5.5. Power Analysis

Post hoc power analysis for the regression model was conducted using the mean remote teaching professional efficacy of individuals with different demographic, teaching, and school characteristics. The alpha error probability was set at 0.05 for the power analysis calculation. Additionally, effect sizes between groups were calculated to assess the magnitude of differences. Cohen’s d was used to measure effect size, calculated by dividing the difference between group means by the pooled standard deviation.

All the statistical analyses, except for power analysis, was performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 29 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), where the level of significance was set to p < 0.05 (2-tailed). Power analysis was calculated using G*Power software 3.1.9.4.

The qualitative analysis of the interviews was performed using Microsoft Excel software to aid in conducting conventional content analysis, following the approach outlined by Hsieh and Shannon (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). This method facilitated data categorization and examination. The two authors independently coded the text responses, identifying keywords, labeling high-frequency words, and categorizing them. Through continuous comparative analysis and revisiting the categories, themes specific to PE teachers emerged. To ensure rigor, a third investigator reviewed and coded the text independently, and any discrepancies among the team were resolved through a final discussion session (Popping, 2015).

2.5.6. Qualitative Data Were Managed and Analyzed Using NVivo, Version 11

The entire dataset, including the complete responses of all participants, was coded by one author (Castleberry & Nolen, 2018). During coding, content relevant to the research aims was specifically identified. A descriptive phenomenological approach was employed to ensure the accurate representation of the data analysis results.

The coded data corresponding to the quantitative variables in the measures, including the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) and the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5), were extracted and compared between the two groups. The teachers’ extracted narratives were translated into English.

3. Results

This section presents the results of this study in line with the research objectives. The quantitative findings focus on identifying factors that influence PE teachers’ professional effectiveness in distance education, examining differences in effectiveness based on demographic variables, and exploring the relationship between professional effectiveness and perceptions of health. The qualitative findings provide deeper insights into the experiences and challenges physical education teachers face in transitioning to distance education and highlight issues such as adaptability, preparation, and gender differences in professional effectiveness. Taken together, these findings contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the factors that shape effective distance PE teaching and inform strategies to support PE teachers in future online teaching scenarios.

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.1.1. Study Participants’, Demographic, Teaching, and School Characteristics

Of the 757 PE teachers participating in this study, 65.7% were female, and the mean age was 46.96 ± 10.20. The mean number of years the participants had been teaching was 17.37 ± 11.09 years; most taught at the elementary school level (n = 392, 51.5% of the sample). The most prevalent school type was the general (secular Jewish) public school system (n = 537, 70.5% of the sample). For additional information, refer to Table 1.

Table 1.

Study participants’ demographic, teaching, and school characteristics (N = 757).

3.1.2. Teachers’ Remote Teaching Professional Efficacy

Statistically significant differences were observed in the prevalence of teachers with poor-to-average professional efficacy and those with high professional efficacy on all 11 questionnaire items (chi-square range: 68.41 on item 10 to 758.12 on item 3; p < 0.001). More specifically, concerning five items, most study participants exhibited high professional efficacy (items 2, 3, 6, 7, and 8), while on six items, most study participants exhibited poor-to-average professional efficacy (items 1, 4, 5, 9, 10, and 11). For a description of the items and additional information, see Table 2.

Table 2.

Teachers’ remote teaching professional efficacy (N = 761).

3.1.3. Remote Teaching Professional Efficacy: Health Perception Differences

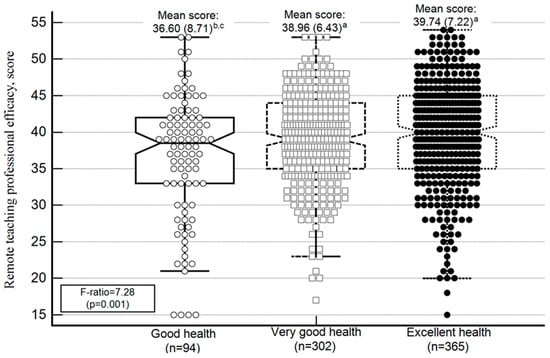

As seen in Figure 1, all study participants reported an overall good health perception. However, in comparison to those with “good health”, participants with “very good health” and “excellent health” had a statistically significantly higher remote teaching professional efficacy (mean scores: 36.60 ± 8.71, 38.96 ± 6.43, and 39.74 ± 7.22, respectively; F-ratio = 7.28, p = 0.001). Similarly, statistically significant positive correlations were observed between the remote teaching efficacy score and health perception (r = 0.22, p < 0.001). Higher remote teaching professional efficacy scores were associated with better general health perceptions.

Figure 1.

Remote teaching professional efficacy: health perception differences. Note: The central box represents the interquartile range (25th–75th percentiles), with the vertical line covering the full data range. Outliers are shown as separate points, defined as values beyond 1.5 times the interquartile range. The central line represents the median.

3.1.4. Factors Influencing Variations Between Participants with Different Levels of Remote Teaching Professional Efficacy

- Demographic Characteristics

No statistically significant correlations were observed between remote teaching professional efficacy and age (p > 0.05). Similarly, no between-group differences in professional efficacy were observed between participants of different religions (t = 3.45, p = 0.06) and family status (f = 3.30, p = 0.07). However, compared to males, females were found to have a statistically significantly higher teaching professional efficacy (mean scores: 37.52 ± 7.30 and 40.82 ± 7.00, t = 17.92, p < 0.001). Similarly, participants with higher educational levels (master’s and doctoral degrees) presented a statistically significantly higher remote teaching professional efficacy than those with lower levels of education (a senior-qualified certificate and bachelor’s degree; 40.69 ± 6.69 and 38.54 ± 7.53, respectively, t = 4.79, p = 0.02). For additional information, see Table 3.

Table 3.

Differences in remote teaching professional efficacy based on categorical socio-demographic, teaching, and school characteristics (N = 761).

- Teaching and School Characteristics

No statistically significant associations were observed between remote teaching professional efficacy and number of years of teaching (p > 0.05). However, as seen in Table 3, teachers in the lower grades (elementary and middle school) presented a statistically significantly greater teaching professional efficacy than those at a higher grade level (high school; f = 3.08, p = 0.04). Statistically significant differences were also observed between participants teaching in different types of schools. More specifically, participants teaching in the state public Jewish schools showed a statistically significantly greater remote teaching professional efficacy than those teaching in Arab schools (f = 3.08, p = 0.04). Finally, teachers teaching in the central and the northern part of the country presented a statistically significantly higher remote teaching professional efficacy compared to teachers teaching in the eastern region of the country (f = 4.38, p = 0.005; Table 3).

- Factors Predicting Remote Teaching Professional Efficacy

Table 4 presents the binary logistic regression results for predicting remote teaching professional efficacy. The regression model explained 17% of the variability in professional efficacy in teaching (chi-squared = 37.44; p < 0.0001; Nagelkerke R2 = 0.17). Factors predicting remote teaching professional efficacy were sex, education level, school type, and school district. More specifically, in comparison to male teachers, female teachers exhibited greater professional efficacy in teaching (coefficient = 0.87, odds ratio = 2.38, p = 0.02); having master’s and doctoral degrees predicted greater professional efficacy vs. having a bachelor’s degree or being a certified senior teacher (coefficient = 1.15, odds ratio = 3.17, p = 0.01). In comparison to teachers in Arab schools, teachers in the Jewish schools exhibited a higher remote professional efficacy (coefficient = 2.01, odds ratio = 0.13, p < 0.001), and finally, teachers in schools in the central and northern part of the country showed greater professional efficacy than teachers in the eastern part of the country (coefficients: 1.70 and 0.99, respectively; odds ratio: 5.48 and 2.69, respectively; p < 0.001 and 0.04, respectively).

Table 4.

Summary of binary logistic regression analysis to predict remote teaching professional efficacy (N = 761).

In Figure 1, the central box is representative of the values from the lower quartile to the upper quartile. The vertical line extends from the minimum value to the maximum value while excluding the outliers (which are displayed as separate points). An outlier was defined as either (1) a value lower than the lower quartile minus 1.5 times the interquartile range, or (2) a value higher than the upper quartile plus 1.5 times the interquartile range. The middle line is representative of the median.

- Teaching Professional Efficacy: Gender Differences

An analysis of teaching professional efficacy scores identified a statistically significant difference between males (n = 258) and females (n = 503). Specifically, females re-ported significantly higher efficacy scores than males (40.82 ± 7.00 vs. 37.52 ± 7.30, respectively; t = 17.92, p < 0.001).

- Power Analysis

Post hoc power analysis for the regression model was conducted with 10 predictors, a sample size of 761, and a mean effect size d of −0.05 (range: −0.03 to 0.38). Using these parameters and setting the alpha error probability at 0.05, the power achieved was 0.99. This indicates that this study had a high likelihood of detecting statistically significant effects, if present, given the sample size and the effect sizes observed.

3.2. Qualitative Results

Three main themes emerged from the in-depth analysis of the responses to the six open questions posed to 15 PE teachers: the rapid transition from face-to-face to distance education; professional efficiency in distance education is a critical element for teaching with technology; and successes and challenges in distance education in physical education.

3.2.1. The Rapid Transition from In-Person to Remote Teaching

During the pandemic, circumstances could change daily, raising many questions regarding remote PE lessons. The Ministry of Education sent instructions directly to the school principals who delivered them to the PE staff. Teachers reported that the instructions were often unclear. The swift shift from in-person to distance learning significantly impacted teachers’ professional efficacy with respect to remote teaching. The sudden change presented challenges such as adapting to online platforms, integrating technology, and maintaining student engagement. Initially, teachers may have experienced uncertainty and self-doubt. However, with time and support, their professional efficacy in remote teaching developed, especially for those who sought professional development opportunities and embraced a growth mindset.

The pandemic forced us to switch to remote teaching immediately. There were teachers for whom the transition was easy and those for whom it was not. There are teachers in high schools who teach PE who have been trained in digital tools, mainly to teach theoretical material. For them, the transition was relatively easy (PE teacher, 45 years old, male).

In contrast, a 50-year-old female PE teacher said, “Undoubtedly, it was a dreadful experience–akin to a teacher attempting to conduct a class trip over Zoom. It simply doesn’t align well. PE, for instance, thrives on social interactions, like engaging in ball games together”.

3.2.2. Professional Efficacy in Remote Teaching Is a Crucial Element for Teaching Using Technology

In the interviews, the PE teachers emphasized that advanced knowledge, specialized training, and higher academic degrees contributed to increased confidence and competence in their ability to engage in remote PE teaching successfully. They highlighted their ability to effectively apply theoretical frameworks and research-based strategies to address diverse student needs.

“With my master’s degree in PE, I have the tools to create meaningful learning experiences in teaching PE online and I apply research-based strategies to do so, which increases the efficacy of my remote teaching” (PE teacher, 47 years old, female).

Another teacher said, “My doctoral studies gave me a broad understanding of effective PE teaching in both traditional and remote settings. This knowledge empowers me to implement evidence-based strategies, increasing my professional efficacy in remote PE teaching”. (PE teacher, 40 years old, female).

PE teachers also claimed that their professional efficacy was the key factor in dealing with technology. Teachers felt that when they had confidence in their ability to deliver an online lesson, they tended to engage more actively in their teaching, such as setting clear objectives and actively looking for useful resources.

3.2.3. Successes and Challenges in Remote Teaching of PE

The quantitative analysis revealed gender disparities among elementary school teachers. The qualitative data shed light on the professional efficacy of female PE teachers. Female PE teachers expressed their ease in utilizing technology for PE classes, demonstrating creative approaches to distance learning, and feeling confident in delivering online PE lessons during the pandemic, compared to their male counterparts. They described their ability to establish strong relationships with students, creating a supportive and inclusive learning environment for the remote teaching of PE. This is seen in the remarks of one female PE teacher, “I see that my students are engaged during the remote lessons, leading me to believe that they resonate well with them”.

Managing a remote PE lesson has been a challenge for the PE teachers. Some of the teachers joined classes with their camera turned off. According to Ministry of Education policy, students were not required to turn their cameras on, which made it difficult for PE teachers as instructors. This was a source of stress among teachers. The cameras that were off were problematic since it prevented teachers from performing the following: 1. tracking attendance, 2. instructing properly, and 3. providing feedback to students when they performed the exercises and praising them. One male PE coordinator said, “I find that remote PE instruction very difficult and frustrating and therefore, I prefer the traditional way”.

4. Discussion

This study utilized a mixed-methods design to delve into the challenges faced by PE teachers in distance learning. Regarding the first objective, the quantitative analysis revealed a positive association between higher remote teaching professional efficacy and better general health perception among PE teachers. Many teachers successfully transitioned to remote teaching while simultaneously managing their mental and physical well-being, caring for vulnerable family members, and even handling their children’s homeschooling (Kim & Asbury, 2020). Previous research on teachers’ professional efficacy during emergency situations highlighted the significance of eLearning system quality and teacher professional efficacy in their willingness to continue online practices (Centeio et al., 2021; Guoyan et al., 2023). Other studies have also shown that higher professional efficacy among teachers is associated with adopting positive educational practices (San-Martín et al., 2020). Our results show a strong relationship between PE teachers’ efficiency in distance learning and their perceived health, with higher efficiency associated with better well-being. While distance learning brought challenges—such as adapting activities and managing technology—it also opened up opportunities for innovative pedagogy. Teachers who already had experience with digital teaching were better able to adapt, highlighting the need for technology training. In addition, female PE teachers reported having more confidence in distance learning than their male counterparts. Strengthening teachers’ digital competencies, institutional support, and well-being can improve distance learning in physical education and turn challenges into opportunities for improved teaching effectiveness and engagement.

The qualitative data provided additional support and showed how the sudden transition from face-to-face to distance learning impacted the professional effectiveness and performance of distance PE teachers during the pandemic. Several PE teachers had difficult experiences and were unable to deliver PE lessons effectively via Zoom. Most teachers had not received adequate professional training for distance education before the pandemic. Remote teaching raises serious questions about the ability to effectively engage in relationships based on caring, well-being, and connectedness in a context that is unpredictable and unknown (Baker et al., 2022; O’Brien et al., 2020).

Recently, remote teaching has become increasingly prevalent in education systems worldwide (Motamedi, 2001). The shift to remote teaching was not by choice and presented numerous challenges, stress, uncertainty, and complexity. However, what pleasantly surprised us was that during these difficulties, some teachers embraced the situation with a positive outlook (Ferri et al., 2020). They viewed the rapid transition to remote learning as an opportunity to explore new pedagogical approaches, foster unique connections and engagement with learners, challenge prevailing knowledge and perceptions among teachers, and adopt a teaching approach that acknowledged and aligned with the shared social realities of that time. These optimistic perspectives highlight the potential for growth and innovation in remote teaching, encouraging a proactive and positive approach to addressing future challenges (Lambert et al., 2024).

The qualitative data supported the need to provide technical knowledge and practice for PE teachers. PE teachers who had the opportunity to practice remote teaching prior to the pandemic had better experiences and reported higher teacher professional efficacy. PE teacher education should include PE remote teaching so that teachers can have the opportunity to gain knowledge, use digital tools, and embrace the new pedagogy. Technology enables adopting flexible and democratic teaching and learning approaches, granting students increased autonomy and control over their learning process, and fostering the development of cognitive competencies and comprehension (Buckingham, 2013). This refers to the extent to which teachers should feel confident in their ability and capable of effectively engaging and educating students in PE remote learning environments by building relationships in an online space. This is a foundation for cultivating a learning community and committing to a process of self-actualization that requires mutual participation and promotes teachers’ and students’ well-being (Luguetti et al., 2022). Teachers should prioritize individualized attention to students’ needs and interests to enhance online teaching and learning, promote collaboration, and nurture creativity. By adapting teaching methods to the digital environment, educators can create an engaging and inclusive virtual classroom experience (Tari et al., 2022).

Moreover, in light of our findings, it is essential to consider the impact of remote teaching on teachers’ health perceptions and well-being and understand the relationship between remote teaching and professional efficacy. Teachers’ health perception can provide valuable insight into the factors that contribute to successful remote teaching practices while also ensuring the overall well-being of PE teachers. By examining this relationship, educational institutions may develop strategies and support systems that prioritize both effective teaching and the well-being of PE teachers, ultimately leading to improved educational outcomes, satisfaction, and professional efficacy.

Gender disparities in teaching professional efficacy have been a topic of interest in educational research. Our study explored demographic factors and found differences between the genders (female and male teachers) regarding their attitudes toward remote teaching. Additionally, female PE teachers demonstrated higher remote teaching professional efficacy and more positive attitudes towards remote learning than male PE teachers. These disparities in teaching professional efficacy may be influenced by societal expectations, gender stereotypes, and differential experiences in the teaching profession (Gray & Leith, 2004; Tiedemann, 2002). Understanding the nature and extent of gender disparities in teaching professional efficacy is crucial for promoting equity and supporting the professional development of all teachers (Bortoleto et al., 2020). While several studies have reported no significant gender differences in teaching efficacy, others have found that female teachers tend to demonstrate higher levels of professional efficacy and confidence in their teaching abilities than their male counterparts (Brandon, 2000; Horvitz et al., 2015).

5. Limitations

There are several limitations to consider regarding the findings of this study. Firstly, this study employed a cross-sectional design with a convenience sample, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Secondly, it is important to conduct further research with larger and more diverse samples, encompassing different geographical locations to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between remote teaching efficacy, health, and school characteristics among PE teachers. Thirdly, the use of a relatively small sample size in this study may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Including larger samples in future research endeavors would enhance statistical power and increase the robustness of the conclusions drawn from the data. Addressing these limitations through future research will contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the complex dynamics between remote teaching efficacy, health perception, and school characteristics among PE teachers. By employing more rigorous methodologies and larger and more diverse samples, and by conducting studies in various contexts, we can advance our knowledge and make informed decisions to optimize remote teaching practices in PE lessons.

6. Conclusions

This study examined PE teachers’ professional efficiency, health perceptions, and pedagogical approaches of physical education teachers in distance learning. The results show that advanced digital teaching skills and research skills significantly increase the effectiveness of distance education, with female teachers showing more confidence than their male counterparts. While perceived health was not the strongest predictor, the qualitative findings suggest that teachers with positive well-being and previous online teaching experience felt more capable and effective. The findings highlight the need for targeted professional development that focuses on technological pedagogy and research skills and is tailored to teachers’ backgrounds. Training programs should equip all physical education teachers with the necessary skills to effectively deliver distance education. In addition, integrating the practice of distance education into physical education’s teacher education programs can increase confidence and preparedness for emergency response. While these findings are based on the Israeli context, they also have broader implications for global education systems seeking to improve distance education preparation and support the professional development of physical education teachers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B.A., K.N., A.Z. and R.T.; methodology, S.B.; software, S.B. and G.G.; validation, S.L., A.G. and A.Z.; formal analysis, A.M.; investigation, R.B.A.; data curation, G.J.; writing—original draft preparation, R.B.A., A.Z., R.T., G.G. and S.B.; writing—review and editing, K.N., A.M., G.J. and S.L.; visualization, A.Z.; supervision, R.T., G.G. and A.Z.; project administration, R.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by grants from the Chief Scientist of the Ministry of Education. Funding number: 483/21.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Ariel University (AU-HEA-RT-20211007).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EUFAPA | European Federation of Adapted Physical Activity |

| PE | Physical Education |

References

- Baker, S., Anderson, J., Burke, R., De Fazio, T., Due, C., Hartley, L., Molla, T., Morison, C., Mude, W., Naidoo, L., & Sidhu, R. (2022). Equitable teaching for cultural and linguistic diversity: Exploring the possibilities for engaged pedagogy in post-COVID-19 higher education. Educational Review, 74(3), 444–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action (pp. 94–106). Englewood Cliffs. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew, K. J., Ntoumanis, N., Cuevas, R., & Lonsdale, C. (2014). Job pressure and ill-health in physical education teachers: The mediating role of psychological need thwarting. Teaching and Teacher Education, 37, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Amotz, R., Green, G., Joseph, G., Levi, S., Manor, N., Ng, K., Barak, S., Hutzler, Y., & Tesler, R. (2022). Remote teaching, self-resilience, stress, professional efficacy, and subjective health among Israeli PE teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education Sciences, 12(6), 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benevene, P., De Stasio, S., & Fiorilli, C. (2020). Editorial: Well-being of school teachers in their work environment. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortoleto, M. A. C., Ontañón Barragán, T., Cardani, L. T., Funk, A., Melo, C. C., & Santos Rodrigues, G. (2020). Gender participation and preference: A multiple-case study on teaching circus at PE in Brazilians schools. Frontiers in Education, 5, 572577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, D. P. (2000). Self-efficacy: Gender differences of prospective primary teachers in Botswana. Research in Education, 64(1), 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, D. (2013). Media education: Literacy, learning and contemporary culture (1st ed.). Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cardullo, V., Wang, C.-H., Burton, M., & Dong, J. (2021). K-12 teachers’ remote teaching self-efficacy during the pandemic. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 14(1), 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleberry, A., & Nolen, A. (2018). Thematic analysis of qualitative research data: Is it as easy as it sounds? Currents in Pharmacy Teaching & Learning, 10(6), 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeio, E., Mercier, K., Garn, A., Erwin, H., Marttinen, R., & Foley, J. (2021). The success and struggles of physical education teachers while teaching online during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education: JTPE, 40(4), 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4(1), 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T. K. F., Lin, T., & Lonka, K. (2021). Motivating online learning: The challenges of COVID-19 and beyond. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 30(3), 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, T. D., Phan, T. T., Vu, T. N. Q., La, T. D., & Pham, V. K. (2024). Digital competence of lecturers and its impact on student learning value in higher education. Heliyon, 10(17), e37318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daw-as, D. M., & Magat, S. M. C. (2022). Lived experiences of physical education instructors in facilitating distance learning education. International Journal of Physical Education Fitness and Sports, 11(4), 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, I., & Sastra Khusuma, I. H. (2020). Teachers’ elementary school in online learning of COVID-19 pandemic conditions. JURNAL IQRA, 5(1), 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, F., Grifoni, P., & Guzzo, T. (2020). Online learning and emergency remote teaching: Opportunities and challenges in emergency situations. Societies, 10(4), 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giladi, A., Koslowsky, M., & Davidovitch, N. (2021). Effort as a mediator of the relationship between English learning self-efficacy and reading comprehension performance in the EFL field: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Higher Education, 11(1), 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, M., Green, G., Zigdon, A., Barak, S., Joseph, G., Marques, A., Ng, K., Erez-Shidlov, I., Ofri, L., & Tesler, R. (2022). The effects of a physical activity online intervention program on resilience, perceived social support, psychological distress and concerns among at-risk youth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Children, 9(11), 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, E., Bertollo, M., Colangelo, A., Carraro, A., & di Fronso, S. (2021). Primary school physical education at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic: Could online teaching undermine teachers’ self-efficacy and work engagement? Sustainability, 13(17), 9830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C., & Leith, H. (2004). Perpetuating gender stereotypes in the classroom: A teacher perspective. Educational Studies, 30(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guoyan, S., Khaskheli, A., Raza, S. A., Khan, K. A., & Hakim, F. (2023). Teachers’ self-efficacy, mental well-being and continuance commitment of using learning management system during COVID-19 pandemic: A comparative study of Pakistan and Malaysia. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(7), 4652–4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, K., & Sol, K. (2021). Online learning during COVID-19: Key challenges and suggestions to enhance effectiveness. Cambodian Journal of Educational Research, 1(1), 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvitz, B. S., Beach, A. L., Anderson, M. L., & Xia, J. (2015). Examination of faculty self-efficacy related to online teaching. Innovative Higher Education, 40(4), 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, M. S., Khan, S. A., & Bidar, M. C. (2022). Self-efficacy of teachers: A review of the literature. Multi-Disciplinary Research Journal, 10(1), 110–116. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, H.-C., & So, W.-Y. (2020). Difficulties of online physical education classes in middle and high school and an efficient operation plan to address them. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L. E., & Asbury, K. (2020). “Like a rug had been pulled from under you”: The impact of COVID-19 on teachers in England during the first six weeks of the UK lockdown. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(4), 1062–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, K., Hudson, C., & Luguetti, C. (2024). What would bell hooks think of the remote teaching and learning in Physical Education during the COVID-19 pandemic? A critical review of the literature. Sport, Education and Society, 29(6), 667–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. S. Y., Fung, W. K., Daep Datu, J. A., & Chung, K. K. H. (2024). Well-being profiles of pre-service teachers in Hong Kong: Associations with teachers’ self-efficacy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Reports, 127(3), 1009–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, N. L., Gullett, S., Howland Cummings, M., & Haug, C. (2020). Challenges of remote teaching for K-12 teachers during COVID-19. Journal of Educational Leadership in Action, 7(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luguetti, C., Enright, E., Hynes, J., & Bishara, J. A. (2022). The (im)possibilities of praxis in online health and physical education teacher education. European Physical Education Review, 28(1), 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeithan, G. K., Rivera, M. O., Mann, L. E., & Mann, L. B. (2021). Strategies to promote meaningful student engagement in online settings. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 9(4), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercier, K., Centeio, E., Garn, A., Erwin, H., Marttinen, R., & Foley, J. (2021). Physical education teachers’ experiences with remote instruction during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education: JTPE, 40(2), 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohnsen, B. (2012). Implementing online physical education. Journal of Physical Education Recreation & Dance, 83(2), 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, V., Carvalho, C., & Santos, N. N. (2021). Creating a supportive classroom environment through effective feedback: Effects on students’ school identification and behavioral engagement. Frontiers in Education, 6, 661736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamedi, V. (2001). A critical look at the use of videoconferencing in United States distance education. Education, 122(2), 386–394. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, W., Adamakis, M., O’ Brien, N., Onofre, M., Martins, J., Dania, A., Makopoulou, K., Herold, F., Ng, K., & Costa, J. (2020). Implications for European physical education teacher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-institutional SWOT analysis. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Cathain, A., Murphy, E., & Nicholl, J. (2008). The quality of mixed methods studies in health services research. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 13(2), 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popping, R. (2015). Analyzing open-ended questions by means of text analysis procedures. Bulletin de Methodologie Sociologique: BMS, 128(1), 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakisheva, A., & Witt, A. (2022). Digital competence frameworks in teacher education—A literature review. Issues and Trends in Learning Technologies, 11(1), 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Martín, S., Jiménez, N., Rodríguez-Torrico, P., & Piñeiro-Ibarra, I. (2020). The determinants of teachers’ continuance commitment to e-learning in higher education. Education and Information Technologies, 25(4), 3205–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S. N., Condés, E., Rubio-Zarapuz, A., Dalamitros, A. A., Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R., Tornero-Aguilera, J. F., & Clemente-Suárez, V. J. (2023). Navigating the new normal: Adapting online and distance learning in the post-pandemic era. Education Sciences, 14(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J., Pu, X., Yadav, K., & Subramnaiyan, M. (2022). A physical education teacher motivation from the self-evaluation framework. Computers & Electrical Engineering: An International Journal, 98, 107772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tari, F., Javadipour, M., Hakimzadeh, R., & Dehghani, M. (2022). Identifying and modeling the successful educational experiences of elementary school teachers in the e-learning environment during the Corona era. Technology of Education Journal (TEJ), 17(1), 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiedemann, J. (2002). Teachers’ gender stereotypes as determinants of teacher perceptions in elementary school mathematics. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 50(1), 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J., Scanlon, D., & Calderón, A. (2022). Digital technology and teacher digital competency in physical education: A holistic view of teacher and student perspectives. Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, 14(3), 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, J. (2020). Should teachers be trained in emergency remote teaching? Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2), 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C., Fritz, H., Bastami, S., Maestre, J. P., Thomaz, E., Julien, C., Castelli, D. M., de Barbaro, K., Bearman, S. K., Harari, G. M., Cameron Craddock, R., Kinney, K. A., Gosling, S. D., Schnyer, D. M., & Nagy, Z. (2021). Multi-modal data collection for measuring health, behavior, and living environment of large-scale participant cohorts. GigaScience, 10(6), giab044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Gao, J., Zhao, L., Liu, Z. Q., & Guan, A. (2025). Predicting college student engagement in physical education classes using machine learning and structural equation modeling. Applied Sciences, 15(7), 3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).