Family Diversity from the Perspective of Early Childhood Education Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

Family Diversity According to Children’s Perspective

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Section 3 (girl version) of “Questionnaire for Children on Family Diversity (Peregrina et al., 2021)”

- How do I perceive family diversity? Answer the following cuestions:

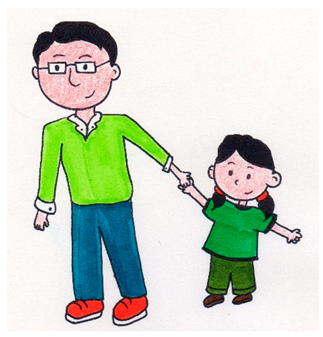

- Family type 1

- Is this a family?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- How happy is the girl in the picture?

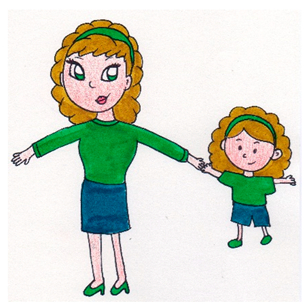

- Family type 2

- Is this a family?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- How happy is the girl in the picture?

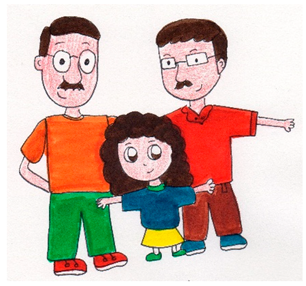

- Family type 3

- Is this a family?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- How happy is the girl in the picture?

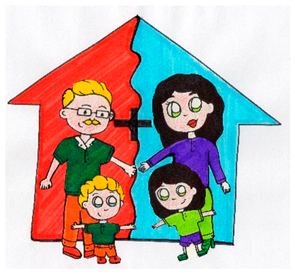

- Family type 4

- Is this a family?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- How happy is the girl in the picture?

- Family type 5

- Is this a family?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- How happy is the girl in the picture?

- Family type 6

- Is this a family?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- How happy is the girl in the picture?

- Family type 7

- Is this a family?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- How happy is the girl in the picture?

- Family type 8

- Is this a family?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- How happy is the girl in the picture?

- Family type 9

- Is this a family?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- How happy is the girl in the picture?

- Family type 10

- Is this a family?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- How happy is the girl in the picture?

- Family type 11

- Is this a family?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- How happy is the girl in the picture?

- Family type 12

- Is this a family?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- How happy is the girl in the picture?

- Family type 13

- Is this a family?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- Family type 14

- Is this a family?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- Family type 15

- Is this a family?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- Family type 16

- Is this a family?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

- Family type 17

- Is this a family?

- ○

- Yes

- ○

- No

References

- Adam, H., Murphy, S., Urquhart, Y., & Ahmed, K. (2024). Where are the diverse families in Australian children’s literature? Impacts and consideration for language and literacy in the early years. Education Sciences, 14(9), 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado, L. (2010). Escuela inclusiva y diversidad de modelos familiares. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 56(3), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, A., & Prades, S. (2015). ¿Qué es la familia? La percepción de los niños de 5 años sobre las familias [Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Jaume I]. Available online: http://repositori.uji.es/xmlui/handle/10234/137345 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Alemán, A. (2021). Diversidad familiar en el contexto escolar. Revista DELOS, Desarrollo Local Sostenible, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA. (2018). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. Rules and procedures. Ethics Committee of the American Psychological Association. Available online: https://www.apa.org/ethics/committee-rules-procedures-2018.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (2003). La construcción social de la realidad. Amorrortu. [Google Scholar]

- Bertram, T., Formosinho, J., Gray, C., Pascal, C., & Whalley, M. (2016). EECERA ethical code for early childhood researchers. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 24(1), 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosisio, R., & Ronfani, P. (2016). ‘Who is in Your Family?’ Italian children with non-heterosexual parents talk about growing up in a non-conventional household. Children & Society, 30, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buendica, G., Díaz García, S. M., Marmolejo, N., & Ospina, M. (2017). ¿Influye la tipología familiar en su dinámica relacional? Textos y sentidos, 17, 11–32. Available online: https://revistas.ucp.edu.co/index.php/textosysentidos/article/view/62 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Bustos Delgado, X., & Arenas Yáñez, T. (2023). Familias monomarentales: Desafíos de las madres trabajadoras estudiantes en Educación Superior, Chile. In C. Hamodi Galán, & L. Álvaro Andaluz (Eds.), El género y su transversalización en la educación (formal y no formal), en la familia y en el deporte (pp. 569–574). Universidad Técnica Federico Santa María. [Google Scholar]

- Cantón, J., Cortés, M. R., & Justicia, M. D. (2002). Las consecuencias del divorcio en los hijos. Psicopatología Clínica, Legal y Forense, 2(3), 47–66. Available online: https://masterforense.com/pdf/2002/2002art16.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Capano, A., González, M. L., & Massonnier, N. (2016). Análisis de ideas de docentes de educación primaria sobre diversidad familiar. Propósitos y Representaciones, 4(2), 15–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Comas-d’Argemir, D. (2018). Bienestar infantil y diversidad familiar. Infancia, parentalidad y políticas públicas en España. Revista de Políticas Sociales Urbanas, 2, 173–194. Available online: https://revistas.untref.edu.ar/index.php/ciudadanias/article/view/537/502 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Correa, L. V., Vargas, E. D., & Gallego, A. M. (2016). El niño y su imaginario de familia. Simposio de Investigación Ustamed. [Google Scholar]

- Crisol, E., & Romero, M. A. (2018). Intervención psicoeducativa en educación infantil. Síntesis. [Google Scholar]

- Crisol, E., & Romero, M. A. (2021). Familia y funciones básicas. Revisión bibliográfica y reformulación teórica. In G. Alba, G. Álvarez, A. Benavides, & A. Justicia (Eds.), Investigaciones y avances en el estudio social y psicoeducativo de las familias diversas (pp. 17–28). Dykinson. [Google Scholar]

- Dessen, M. A., & Campos, P. C. (2010). Niños de edad preescolar y sus concepciones de la familia. Paidéia, 20(47), 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eerola, P., Paananen, M., & Repo, K. (2023). Ordinary and diverse families. A case study of family discourses by Finnish early childhood education and care administrators. Journal of Family Studies, 29(2), 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Llera, R., & Muñiz, M. (2012). Colegios concertados y selección de escuela en España: Un círculo vicioso. Presupuesto y Gasto Público, 67, 97–118. Available online: https://digibuo.uniovi.es/dspace/handle/10651/11028 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Golani, N., Nasie, M., & Carmel, O. (2024). Families come in many forms: Attitudes and practices of Israeli kindergarten teachers towards diverse families. Early Child Development and Care, 194(5–6), 753–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedberg, L., Venzo, P., & Young, H. (2022). Mums, dads and the kids: Representations of rainbow families in children’s picture books. Journal of LGBT Youth, 19(2), 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, O. (2021). Acercamiento a los diferentes tipos de muestreo no probabilístico que existen. Revista Cubana de Medicina General Integral, 37(3), 1–3. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/mgi/v37n3/1561-3038-mgi-37-03-e1442.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Herrera, P. (2000). Rol de género y funcionamiento familiar. Revista Cubana de Medicina General Integral, 16(6), 568–573. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/mgi/v16n6/mgi08600.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). (2023). Cifras oficiales de población resultantes de la revisión del Padrón municipal. Año 2023. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736177010&menu=resultados&secc=1254736195526&idp=1254734710990 (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Irueste, P., Guatrochi, M., Pacheco, S., & Delfederico, F. (2018). New family configurations: Types of family, functions and family structure. Revista de Psicoterapia Relacional e Intervenciones Sociales, 41, 11–18. Available online: https://www.redesdigital.com/index.php/redes/article/view/44 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Jeffries, M. (2024). ‘The standard system… is heteronormative’: Deconstructing the (re)production of ‘family’ in schools using a binary lens. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, F., Díez, M., Morgado, B., & González, M. M. (2008). Educación infantil y diversidad familiar. Revista de Educación, 10, 111–122. Available online: https://rabida.uhu.es/dspace/bitstream/handle/10272/2145/b15480057.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Mota, R., Hamburguer, J., & Vidal, F. (2018). La modernidad de una sociedad familiar. Informe Familia 2017. Padres y Maestros, 374, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, C., Moreno, C., Rivera, F., & Jiménez-Iglesias, A. (2018). ‘Adolescents’ perceptions of family relationships in adoptees and non-adoptees: More similarities than differences’. British Journal of Social Work, 49(1), 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peregrina, P., Caurcel, M. J., & Crisol, E. (2021). Cuestionario para menores sobre Diversidad Familiar. (Unpublished manuscript).

- Peregrina-Nievas, P., Caurcel-Cara, M. J., & Crisol, E. (2023). Analyzing family diversity in the educational context: A systematic review. International Journal of Diversity in Education, 23(1), 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poveda, D., Jociles, M. I., & Rivas, A. M. (2011). Single-parenthood by choice: Children’s socialization processes into a nonconventional family model. Athenea Digital, 11(2), 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, E. (2018). The heterogeneity of family: Responses to representational invisibility by LGBTQ parents. Journal of Family Issues, 39(18), 4204–4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendón-Macías, M. E., Zarco-Villavicencio, I. S., & Villasís-Keever, M. Á. (2021). Métodos estadísticos para el análisis del tamaño del efecto. Revista Alergia México, 68(2), 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Chaves, B., Esteban-Mora, J., & Granero-Andújar, A. (2025). Binarismo de género en el material didáctico de editoriales de educación infantil: Análisis axiológico de contenido. Revista del Laboratorio Iberoamericano para el Estudio Sociohistórico de las Sexualidades, 13(2), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urdiales, I., Caurcel, M., & Crisol, E. (2021). La Diversidad Familiar desde la perspectiva de los futuros docentes de Educación Infantil: Necesidades formativas. Revista Complutense de Educación, 32(3), 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, D., & Neves, M. F. (2019). A diversidade familiar em contexto educativo [Family diversity in education context]. Exedra, 1, 144–165. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7304930 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- World Medical Association (WMA). (2013, October 19). Declaration of Helsinki ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. 64th General Assembly, Fortaleza, Brazil. Available online: https://www.wma.net/es/policies-post/declaracion-de-helsinki-de-la-amm-principios-eticos-para-las-investigaciones-medicas-en-seres-humanos/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Yucra Quispe, T., & Bernedo Villalta, L. Z. (2020). Epistemología e investigación cuantitativa. Revista Igobernanza, 3(12), 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Family Types | No | Yes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| A male and female couple with children | 7 | 4.50 | 149 | 95.50 |

| A male and female couple with children and grandparents | 8 | 5.10 | 148 | 94.90 |

| A male and female couple from different nationalities with children | 11 | 7.10 | 145 | 92.90 |

| A male and female couple with adoptive children | 12 | 7.70 | 143 | 92.30 |

| A female couple with children | 45 | 28.80 | 111 | 71.20 |

| A male and female couple | 45 | 29.00 | 110 | 71.00 |

| A male couple with children | 47 | 30.10 | 109 | 69.90 |

| A male and female couple from divorced couples with children | 49 | 31.60 | 106 | 68.40 |

| A female couple | 65 | 41.70 | 91 | 58.30 |

| A woman with children | 65 | 41.70 | 91 | 58.30 |

| A male couple | 71 | 45.50 | 85 | 54.50 |

| A man with children | 76 | 48.70 | 80 | 51.30 |

| A male and female divorced couple with children | 85 | 54.50 | 71 | 45.50 |

| A person with a pet | 88 | 56.80 | 67 | 43.20 |

| A teacher and her students | 92 | 54.40 | 63 | 40.60 |

| A group of children | 97 | 62.20 | 59 | 37.80 |

| A person alone | 121 | 77.60 | 35 | 22.40 |

| Family Types | M | SD | Mo | % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||

| A male and female couple with children and grandparents | 4.17 | 0.60 | 4 | 1.30 | 0.00 | 3.20 | 71.20 | 24.40 |

| A male and female couple from different nationalities with children | 4.13 | 0.69 | 4 | 0.60 | 1.90 | 8.30 | 62.20 | 26.90 |

| A male and female couple with children | 4.12 | 0.80 | 4 | 3.20 | 1.30 | 2.60 | 65.60 | 27.30 |

| A male and female couple with adoptive children | 4.08 | 0.67 | 4 | 1.30 | 0.60 | 9.00 | 67.10 | 21.90 |

| A teacher and her students | 4.05 | 0.76 | 4 | 0.60 | 4.50 | 9.00 | 61.30 | 24.50 |

| A male and female couple from divorced couples with children | 3.97 | 0.87 | 4 | 2.00 | 3.30 | 17.00 | 51.00 | 26.80 |

| A female couple with children | 3.92 | 0.81 | 4 | 1.90 | 4.50 | 12.20 | 62.80 | 18.60 |

| A group of children | 3.88 | 1.05 | 4 | 5.80 | 5.80 | 9.00 | 53.50 | 25.80 |

| A woman with children | 3.87 | 0.81 | 4 | 2.60 | 3.80 | 12.80 | 65.40 | 15.40 |

| A male couple with children | 3.86 | 0.85 | 4 | 1.90 | 6.50 | 12.30 | 61.70 | 17.50 |

| A man with children | 3.78 | 0.93 | 4 | 3.20 | 7.10 | 16.00 | 55.80 | 17.90 |

| A male and female divorced couple with children | 3.61 | 0.99 | 4 | 5.80 | 7.10 | 20.00 | 54.80 | 12.30 |

| Family Types | Age | N | M | SD | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A man with children | 3 | 19 | 0.79 | 0.42 | 7.138 | 0.000 * | 0.108 |

| 4 | 43 | 0.70 | 0.47 | ||||

| 5 | 76 | 0.38 | 0.49 | ||||

| 6 | 18 | 0.33 | 0.48 | ||||

| A woman with children | 3 | 19 | 0.89 | 0.31 | 7.291 | 0.000 * | 0.097 |

| 4 | 43 | 0.74 | 0.44 | ||||

| 5 | 76 | 0.43 | 0.50 | ||||

| 6 | 18 | 0.50 | 0.51 | ||||

| A male couple with children | 3 | 19 | 0.68 | 0.48 | 5.587 | 0.001 * | 0.046 |

| 4 | 43 | 0.88 | 0.32 | ||||

| 5 | 76 | 0.67 | 0.47 | ||||

| 6 | 18 | 0.39 | 0.50 | ||||

| A male and female divorced couple with children | 3 | 19 | 0.79 | 0.42 | 6.651 | 0.000 * | 0.116 |

| 4 | 43 | 0.56 | 0.50 | ||||

| 5 | 76 | 0.38 | 0.49 | ||||

| 6 | 18 | 0.17 | 0.38 | ||||

| A male and female couple from divorced couples with children | 3 | 19 | 0.89 | 0.31 | 4.426 | 0.005 * | 0.077 |

| 4 | 43 | 0.81 | 0.39 | ||||

| 5 | 76 | 0.60 | 0.49 | ||||

| 6 | 18 | 0.50 | 0.51 | ||||

| A teacher and her students | 3 | 19 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 2.966 | 0.034 * | 0.050 |

| 4 | 43 | 0.44 | 0.50 | ||||

| 5 | 76 | 0.39 | 0.50 | ||||

| 6 | 18 | 0.17 | 0.38 | ||||

| A group of children | 3 | 19 | 0.68 | 0.48 | 5.391 | 0.001 * | 0.090 |

| 4 | 43 | 0.49 | 0.51 | ||||

| 5 | 76 | 0.28 | 0.45 | ||||

| 6 | 18 | 0.22 | 0.43 | ||||

| A person alone | 3 | 19 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 11.361 | 0.000 * | 0.173 |

| 4 | 43 | 0.30 | 0.47 | ||||

| 5 | 76 | 0.13 | 0.34 | ||||

| 6 | 18 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| A person alone with pets | 3 | 19 | 0.74 | 0.45 | 4.591 | 0.004 * | 0.062 |

| 4 | 43 | 0.52 | 0.50 | ||||

| 5 | 76 | 0.32 | 0.47 | ||||

| 6 | 18 | 0.39 | 0.50 |

| Family Types | Age | N | M | SD | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A man with children | 3 | 19 | 4.26 | 0.45 | 3.435 | 0.019 * | 0.107 |

| 4 | 43 | 3.18 | 1.01 | ||||

| 5 | 76 | 3.72 | 0.95 | ||||

| 6 | 18 | 3.33 | 0.84 | ||||

| A male and female divorced couple with children | 3 | 19 | 3.79 | 0.71 | 5.005 | 0.002 * | 0.082 |

| 4 | 42 | 3.90 | 0.76 | ||||

| 5 | 76 | 3.57 | 1.01 | ||||

| 6 | 18 | 2.89 | 1.28 |

| Family Types | Location | N | M | SD | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A male and female couple from divorced couples with children | Beiro | 37 | 0.86 | 0.35 | 10.75 | 0.00 * | 0.109 |

| Zaidín | 44 | 0.82 | 0.39 | ||||

| Externa | 74 | 0.51 | 0.50 | ||||

| A teacher and her students | Beiro | 37 | 0.62 | 0.50 | 8.68 | 0.00 * | |

| Zaidín | 43 | 0.19 | 0.50 | 0.011 | |||

| Externa | 75 | 0.43 | 0.50 |

| Family Types | District | N | M | SD | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A male and female couple with children and grandparents | Beiro | 37 | 4.24 | 0.80 | 6.00 | 0.003 * | 0.165 |

| Zaidín | 44 | 4.39 | 0.75 | ||||

| External | 75 | 4.01 | 0.26 | ||||

| A man with children | Beiro | 37 | 3.38 | 1.26 | 5.63 | 0.004 * | 0.262 |

| Zaidín | 44 | 4.05 | 1.12 | ||||

| External | 75 | 3.83 | 0.45 | ||||

| A woman with children | Beiro | 37 | 3.51 | 1.26 | 6.43 | 0.002 * | 0.199 |

| Zaidín | 44 | 4.14 | 0.73 | ||||

| External | 75 | 3.89 | 0.42 | ||||

| A male couple with children | Beiro | 37 | 3.54 | 1.26 | 8.23 | 0.000 * | 0.219 |

| Zaidín | 42 | 4.26 | 0.77 | ||||

| External | 75 | 3.80 | 0.49 | ||||

| A female couple with children | Beiro | 37 | 3.70 | 1.18 | 4.48 | 0.013 * | 0.218 |

| Zaidín | 44 | 4.20 | 0.26 | ||||

| External | 75 | 3.85 | 0.23 | ||||

| A male and female couple from different nationalities with children | Beiro | 37 | 4.11 | 1.02 | 14.66 | 0.000 * | 0.246 |

| Zaidín | 44 | 4.55 | 0.50 | ||||

| External | 75 | 3.89 | 0.42 | ||||

| A male and female couple with adoptive children | Beiro | 37 | 4.11 | 0.94 | 6.29 | 0.002 * | 0.152 |

| Zaidín | 44 | 4.34 | 0.68 | ||||

| External | 74 | 3.91 | 0.41 | ||||

| A male and female couple from divorced couples with children | Beiro | 37 | 4.35 | 0.89 | 10.75 | 0.000 * | 0.319 |

| Zaidín | 44 | 4.11 | 1.13 | ||||

| External | 72 | 3.69 | 0.52 | ||||

| A teacher and her students | Beiro | 37 | 3.95 | 1.08 | 4.92 | 0.009 * | 0.217 |

| Zaidín | 44 | 4.34 | 0.83 | ||||

| External | 74 | 3.92 | 0.40 | ||||

| A group of children | Beiro | 37 | 3.35 | 1.48 | 8.61 | 0.000 * | 0.281 |

| Zaidín | 44 | 4.27 | 1.11 | ||||

| External | 74 | 3.91 | 0.53 |

| Family Types | Public (n = 119) | Public–Private (n = 37) | t | p | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| A male and female couple with children | 0.97 | 0.16 | 0.89 | 0.32 | 2.15 | 0.034 * | 0.316 |

| A man with children | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 2.27 | 0.024 * | 0.429 |

| A male and female couple from divorced couples with children | 0.63 | 0.49 | 0.86 | 0.35 | −2.76 | 0.006 * | 0.540 |

| A teacher and her students | 0.34 | 0.48 | 0.62 | 0.49 | −3.13 | 0.002 * | 0.577 |

| Family Types | Public (n = 119) | Public–Private (n = 37) | t | p | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| A man with children | 3.91 | 0.77 | 3.38 | 1.26 | 3.10 | 0.002 * | 0.508 |

| A woman with children | 3.98 | 0.57 | 3.51 | 1.26 | 3.17 | 0.002 * | 0.481 |

| A male couple with children | 3.97 | 0.64 | 3.54 | 1.26 | 2.71 | 0.007 * | 0.430 |

| A male and female couple from divorced couples with children | 3.85 | 0.83 | 4.35 | 0.89 | −3.13 | 0.002 * | 0.581 |

| A group of children | 4.04 | 0.81 | 3.35 | 1.48 | 3.64 | 0.000 * | 0.578 |

| Family Types | Upbringing Family | N | M | SD | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A male and female couple with children | Nuclear | 138 | 0.96 | 0.19 | 4.44 | 0.013 * | 0.002 |

| One-mother | 8 | 0.75 | 0.47 | ||||

| Divorced | 10 | 1.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| A male and female couple with children and grandparents | Nuclear | 138 | 0.96 | 0.61 | 3.70 | 0.027 * | 0.001 |

| One-mother | 8 | 0.75 | 0.35 | ||||

| Divorced | 10 | 1.00 | 0.52 | ||||

| A male couple with children | Nuclear | 138 | 0.73 | 0.44 | 4.59 | 0.012 * | 0.022 |

| One-mother | 8 | 0.25 | 0.46 | ||||

| Divorced | 10 | 0.60 | 0.51 | ||||

| A male couple | Nuclear | 138 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 3.71 | 0.027 * | 0.024 |

| One-mother | 8 | 0.13 | 0.35 | ||||

| Divorced | 10 | 0.40 | 0.51 | ||||

| A female couple | Nuclear | 138 | 0.62 | 0.49 | 4.80 | 0.010 * | 0.033 |

| One-mother | 8 | 0.13 | 0.35 | ||||

| Divorced | 10 | 0.40 | 0.51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peregrina-Nievas, P.; Caurcel-Cara, M.J.; Crisol-Moya, E.; Cid-González, C. Family Diversity from the Perspective of Early Childhood Education Students. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040456

Peregrina-Nievas P, Caurcel-Cara MJ, Crisol-Moya E, Cid-González C. Family Diversity from the Perspective of Early Childhood Education Students. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(4):456. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040456

Chicago/Turabian StylePeregrina-Nievas, Paula, María Jesús Caurcel-Cara, Emilio Crisol-Moya, and Christian Cid-González. 2025. "Family Diversity from the Perspective of Early Childhood Education Students" Education Sciences 15, no. 4: 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040456

APA StylePeregrina-Nievas, P., Caurcel-Cara, M. J., Crisol-Moya, E., & Cid-González, C. (2025). Family Diversity from the Perspective of Early Childhood Education Students. Education Sciences, 15(4), 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040456