The results of the online questionnaire survey among teachers and the responses from the interviews are summarized below.

3.2. Answers to Questions

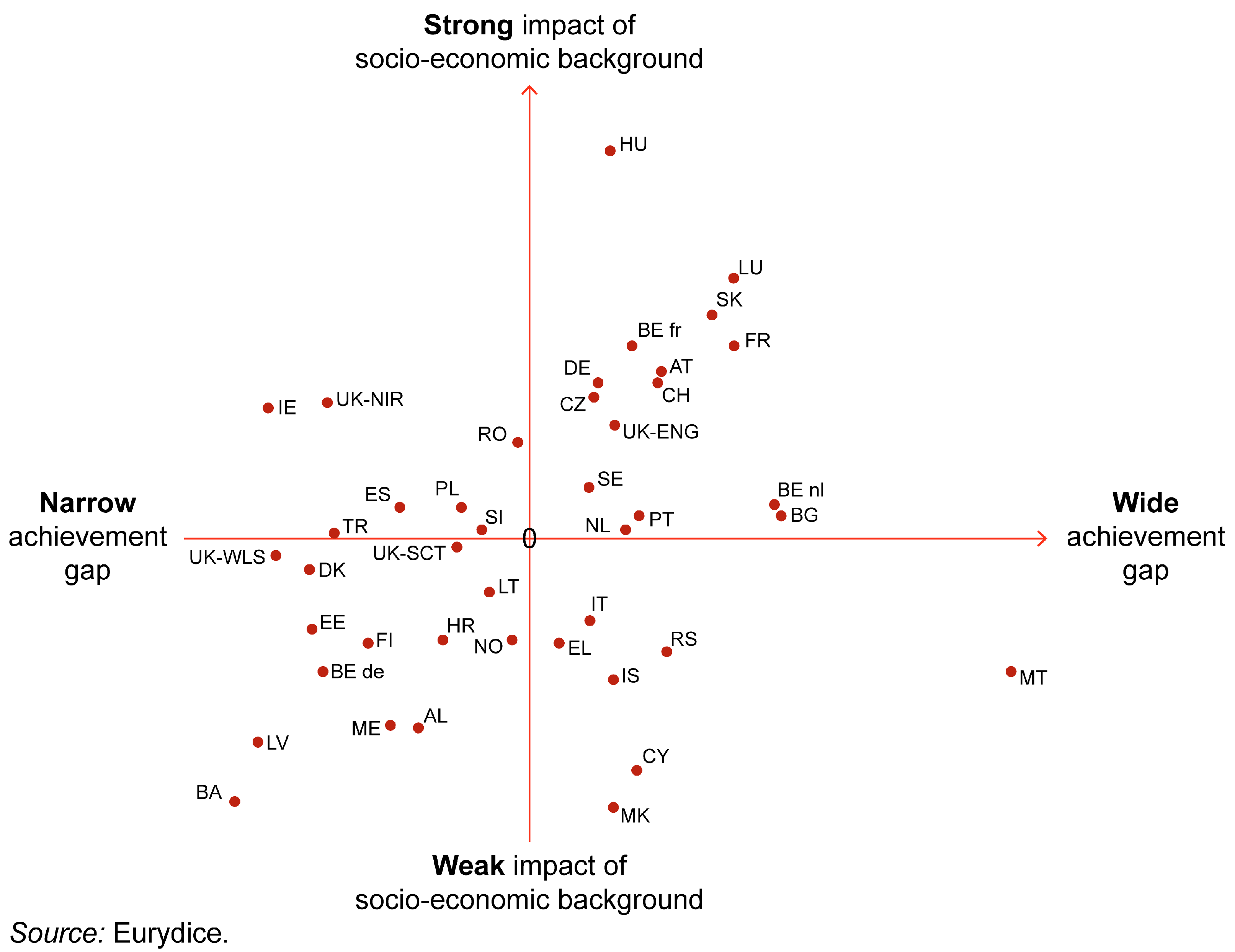

The first item (Item 1,

Figure 4) shown below aimed to explore teachers’ general opinions on whether Roma students are capable of completing school.

Item 1.

- ➢

The majority of Roma students are unable to graduate from lower secondary school. - ➢

Roma students can complete lower secondary school just like students from the majority society.

|

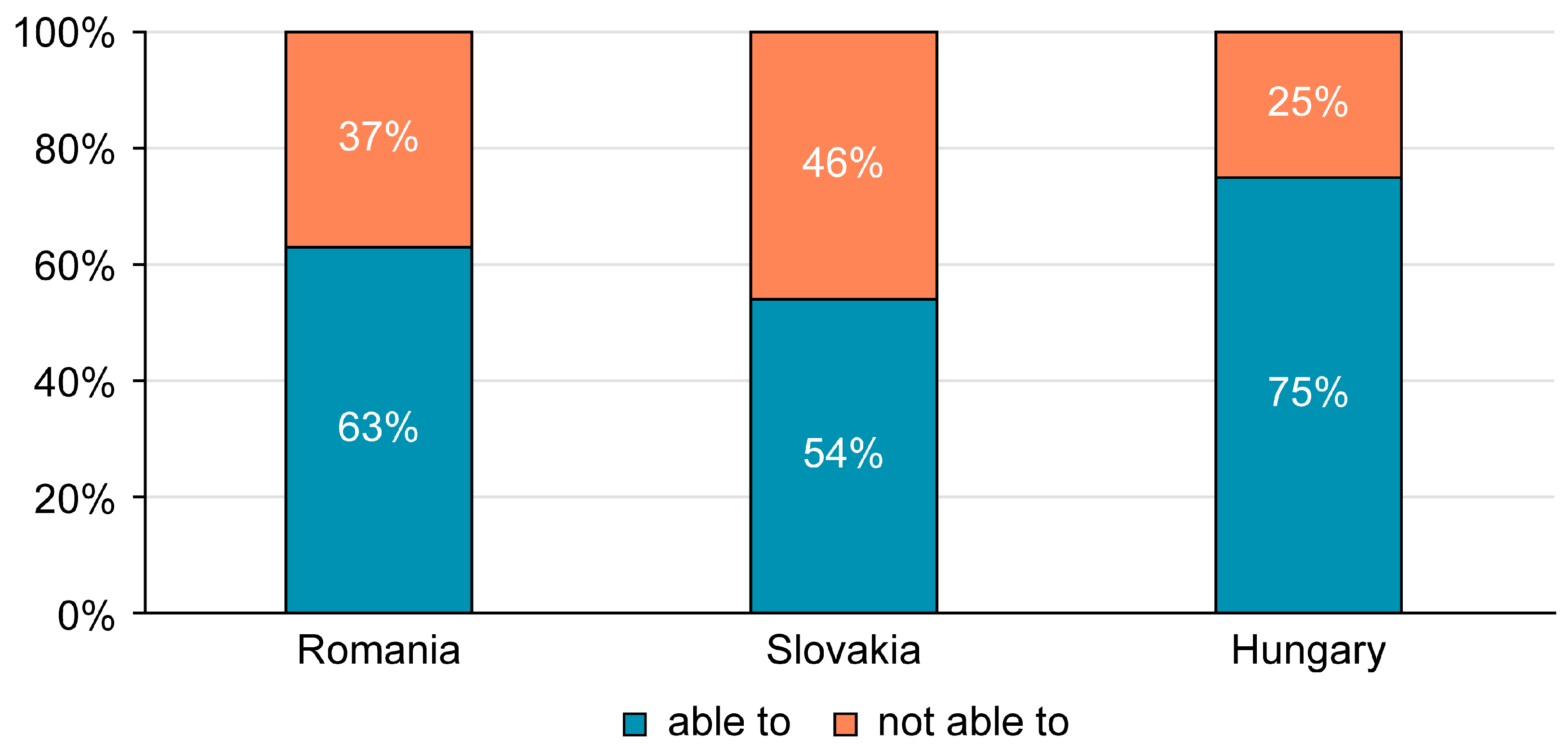

On average, only 65% of the respondents believed that Roma youth are capable of completing lower secondary school. However, this perception varied by country. In Romania, where the Roma population exceeds 10%, 63% of the respondents believed that Roma students could complete school. In Slovakia, where the Roma population is around 13%, this figure dropped to 54%. In Hungary, which has the smallest Roma population of the three countries (7%), 75% of the respondents considered it possible for Roma students to finish at least lower secondary school.

Here, we highlight a trend: countries with a higher proportion of Roma in the population (such as Slovakia and Romania) tend to be less optimistic about Roma students’ ability to complete lower secondary school. However, these responses reflect the general conditions in each country rather than the situation in the respondents’ own schools.

We believe that in schools where Roma students are not segregated, teachers have firsthand experience that encourages them to think that Roma students can complete at least lower secondary education.

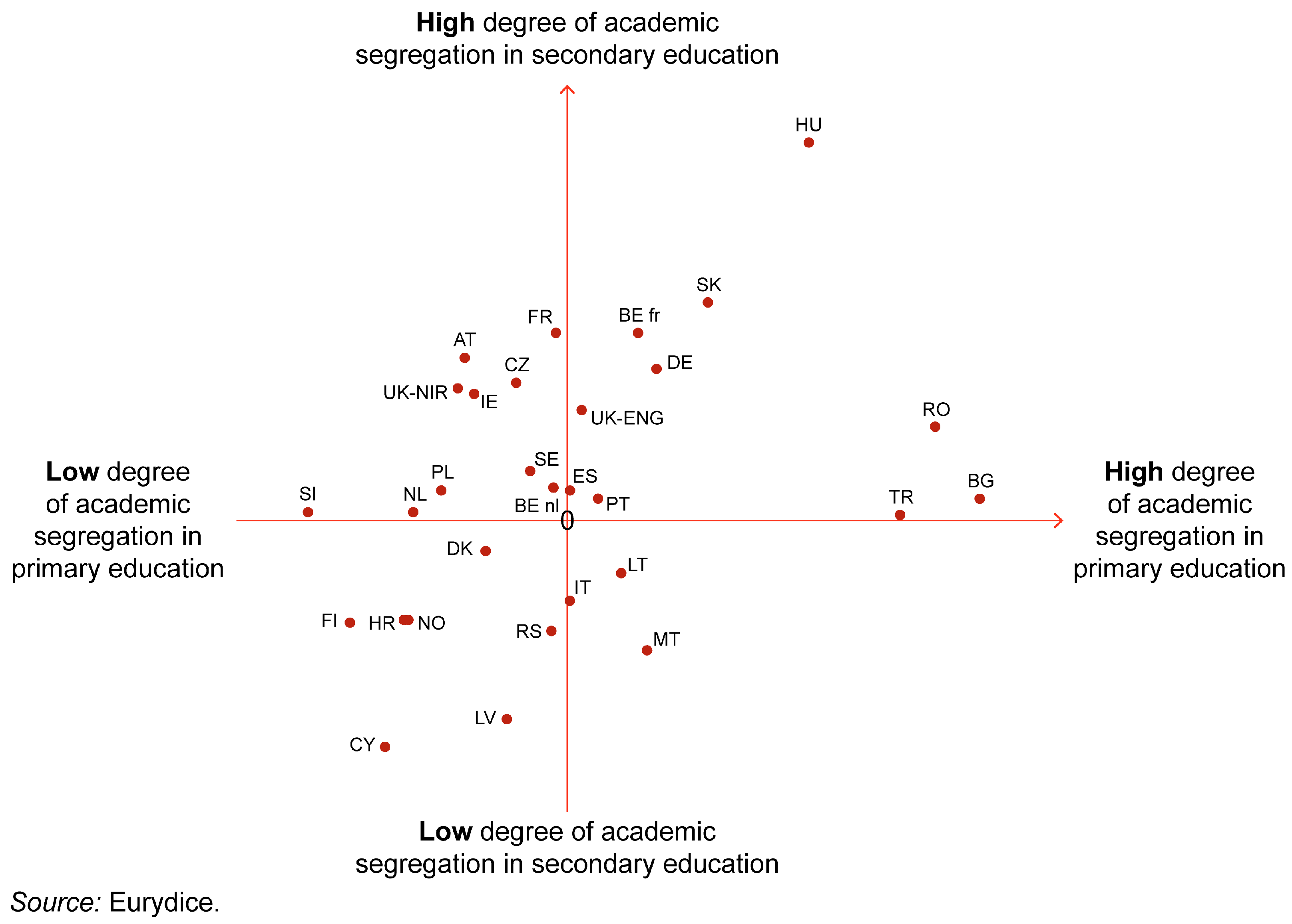

Figure 5 shows that the number of young Roma people entering the labor market decreases significantly when it comes to completing upper secondary education.

Since there were no significant differences in the responses to the additional questions across the three countries examined, the data were analyzed collectively rather than separately by country.

The next item (Item 2) on the multiple-choice questionnaire (response analysis 2–5) concerns the school performance and academic success of Roma students.

Item 2.

- ➢

Roma students hinder high-quality teaching. - ➢

Roma students do not hinder high-quality teaching.

|

We consider it important to highlight that 84% of the teachers in the schools with non-segregated Roma students believed that these students did not struggle to achieve successful education. This indicates that the presence and teaching of Roma students in the classroom are not seen as problematic by most teachers.

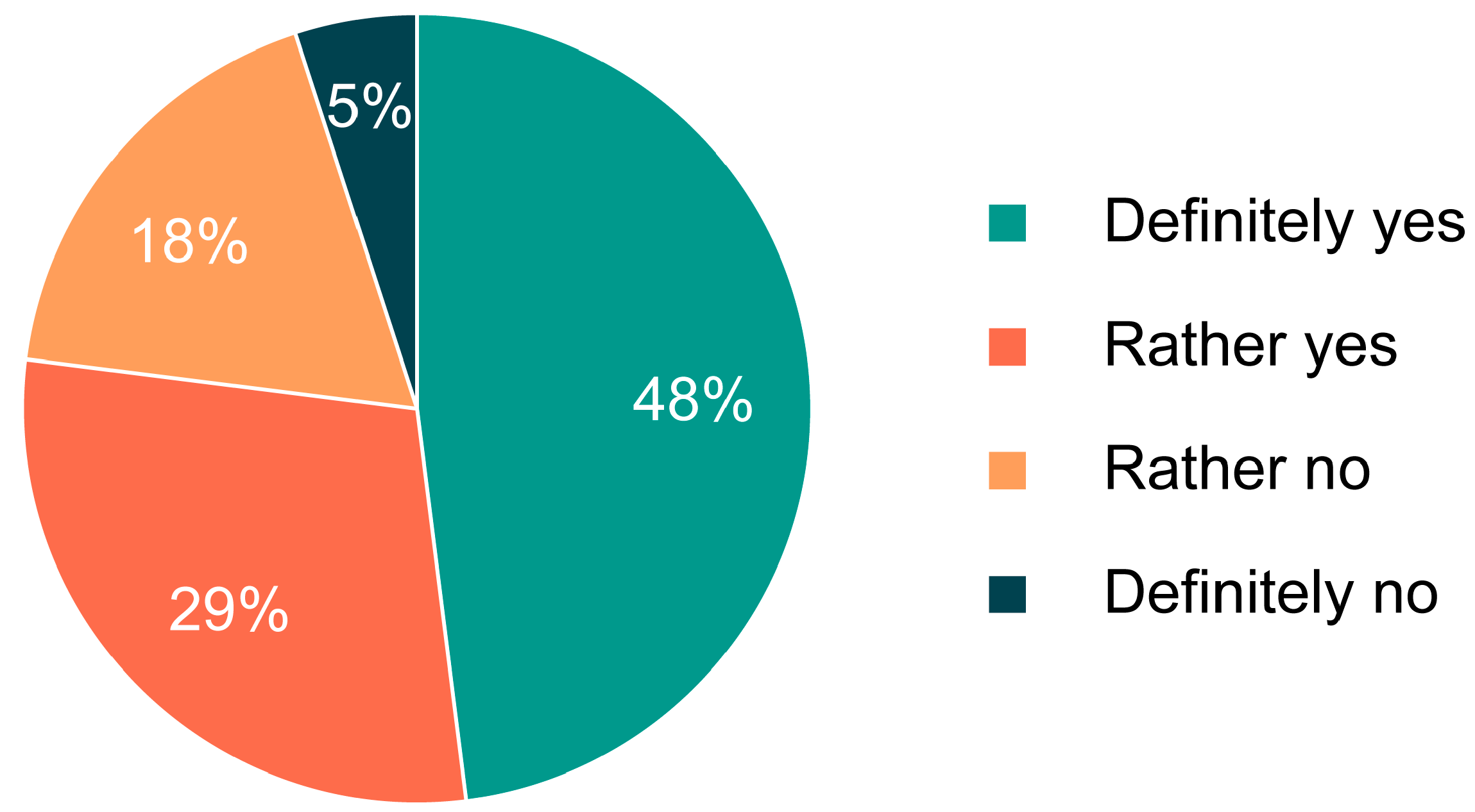

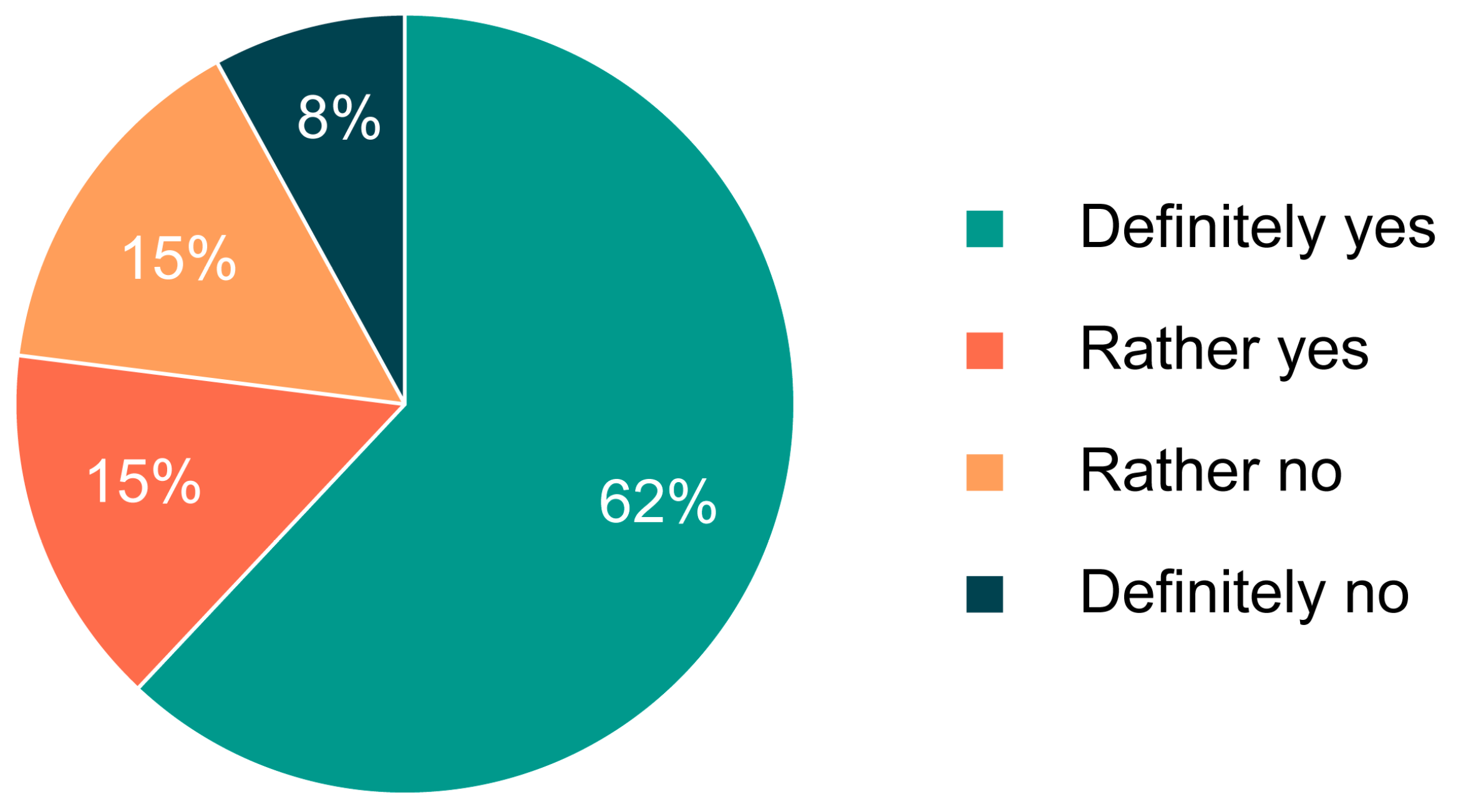

The next item (Item 3,

Figure 6) of the multiple-choice questionnaire also concerns the school performance and academic success of Roma students. For this item, we used a four-point Likert scale: “definitely yes”, “rather yes”, “rather no”, and “definitely no”.

Item 3.- ➢

Schools should do everything possible to ensure that learning for Roma students goes smoothly.

|

About half of the teachers agreed that schools should make every effort to help Roma students learn more effectively. This suggests that in schools where the proportion of Roma students is within reasonable limits, teachers can take their presence into consideration and “manage” it. By “managing”, we mean implementing positive discrimination (e.g., extra lessons) and organizing work in a way that addresses individual needs. We would also like to highlight that nearly a quarter of teachers disagreed with this statement, meaning that they believed that Roma students did not need additional help to achieve adequate performance.

The next item (Item 4,

Figure 7) of the multiple-choice questionnaire concerns families. We used a four-point Likert scale: “definitely yes”, “rather yes”, “rather no”, and “definitely no”.

Item 4.- ➢

Roma students and their families must ensure that their children complete their secondary education. The secondary school has no responsibility in this regard.

|

According to the majority of the respondents (77%), it is primarily the responsibility of Roma families to support their children in successfully completing their studies. However, some of the teachers also believed that schools share this responsibility. Based on the responses, we assume that teachers working with Roma students in non-segregated settings teach Roma students from families whose parents can adequately support their children in further education.

The next item of the questionnaire (Item 5) concerns the requirements placed on Roma students. We asked the teachers to respond with “yes” or “no” to the following question.

Item 5.- ➢

Roma students must meet the same requirements during their studies as their non-Roma peers.

|

We did not create a graph for this response because almost all respondents (95%) opposed reducing the requirements for Roma students. This opposition suggests that the respondents did not perceive any issues with the education of Roma students.

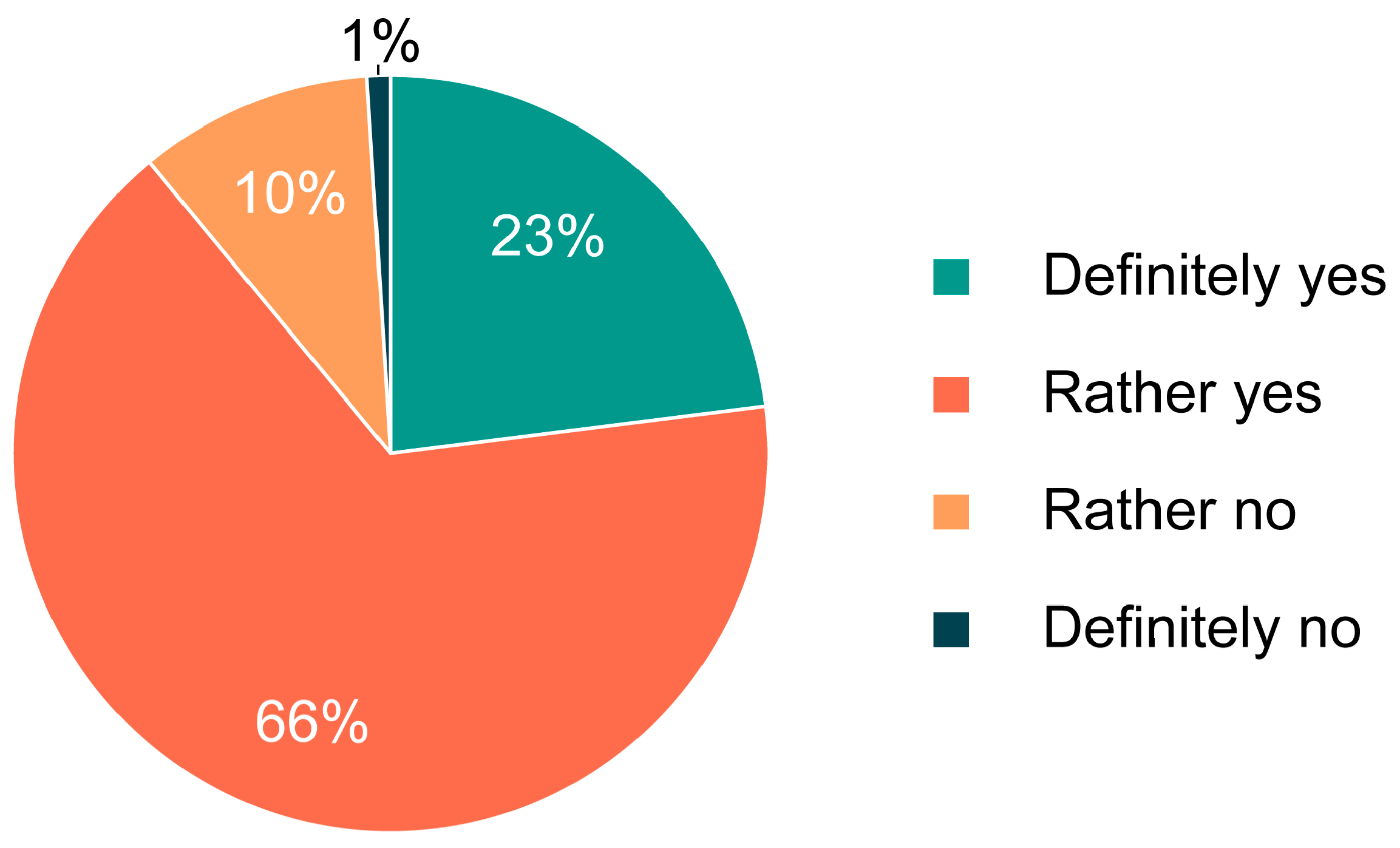

The next item (Item 6,

Figure 8) of the multiple-choice questionnaire concerns the appropriate preparation of teachers. We use a four-point Likert scale: “definitely yes”, “rather yes”, “rather no”, and “definitely no”.

Item 6. - ➢

The teachers are prepared to adequately teach the Roma students.

|

The 89% positive response rate (23% “definitely yes”, 66% “rather yes”) to the above question indicates that the teachers who felt prepared to teach Roma students, i.e., where the proportion of Roma students was not over-represented, did not find their presence problematic.

The next item (Item 7) of the multiple-choice questionnaire was an open question concerning the need for teacher support.

Item 7.- ➢

In which areas do you need help teaching Roma students?

|

The respondents were asked to select multiple areas in which they required assistance for teaching Roma students. The three most frequently mentioned areas of support were the following:

- -

Methodological help—The teachers expressed a need for effective teaching methods that could better address the specific challenges of Roma students;

- -

Access to specialist literature—Many of the respondents highlighted the importance of having resources tailored to the unique needs of Roma students;

- -

Experiential teacher training—The respondents emphasized the value of training courses that offer practical, hands-on experience, helping them to improve their teaching strategies for Roma students.

These areas were identified as crucial for ensuring the successful education of Roma students and for enhancing the teachers’ effectiveness in the classroom.

3.2.1. Summary of Answers to Online Questions

The questionnaire covered three main topics, with the first focusing on the teachers’ perceptions of Roma students’ ability to complete primary education. The results suggest that in countries with a higher Roma population, teachers have more reservations, and a significant portion of teachers believe that Roma students’ presence hinders high-quality teaching, reflecting potential biases or concerns.

The second section of the questionnaire examined teachers’ perspectives on the treatment of Roma students. Most of the teachers did not see difficulties in teaching Roma students, though some viewed their presence as a challenge, possibly due to biases or structural issues. Opinions were divided on whether schools should provide extra support, with some emphasizing the need for additional help, while others advocated for equal treatment. The teachers also highlighted the importance of family involvement in education, and while the majority opposed lowering academic standards, this did not necessarily mean that they believed Roma students could succeed without extra support.

Most of the teachers felt confident and well prepared to teach Roma students, but it remains unclear whether their preparedness fully addresses the unique cultural and educational needs of these students or if additional training and support are needed.

Although many of the teachers felt prepared to teach Roma students, they emphasized the need for methodological support, specialist literature, and training to effectively address the specific challenges that these students may face.

3.2.2. The Pedagogical Culture of Principals: Summary of Answers to Interview Questions About Roma Students

The survey was conducted with six principals from eight schools (two Romanian, one Slovak, and three Hungarian).

A thematic analysis was carried out to identify key themes emerging from the principals’ responses. This method involved systematically categorizing data.

The coding process followed these steps:

Initial coding—The responses were broken down into meaningful segments and assigned preliminary labels based on key topics (e.g., “extra work”, “integration challenges”, “positive discrimination”, and “teacher training”);

Axial coding—Connections between codes were established, grouping related themes into broader categories (e.g., “educational challenges”, “support strategies”, “attitudes toward positive discrimination”);

Selective coding—Core themes were identified, summarizing the overall narrative provided by the respondents.

The majority of the respondents indicated that educating Roma students did not require extra work, and the teachers felt adequately prepared to teach them in these schools. The principals stated that they had the necessary training and resources to manage diverse classrooms, which included teaching Roma students. They emphasized that, for the most part, Roma students integrate well into the regular curriculum without additional challenges. This smaller proportion of Roma students means that educators can offer individual attention to those who may need it without overwhelming their workload.

Moreover, the principals who expressed concerns noted that the challenges that they faced were not unique to Roma students but were common in any diverse classroom. They said that Roma students benefit from a structured approach and clear expectations. In cases where difficulties arose, the principals reported addressing them through additional support such as tutoring, adjusted teaching methods, or collaboration with specialized staff. However, these measures were not viewed as extraordinary but rather as part of regular teaching practices aimed at ensuring all students succeed. Overall, the responses suggested that the education of Roma students is seen as an integral part of the school system, not requiring additional resources or extraordinary effort beyond what is typically needed for students.

The respondents generally believed that schools provide Roma students with the necessary conditions to complete their studies smoothly, ensuring equal access to education. They pointed out that Roma students are included in the same educational programs and have the same resources as other students. The principals felt that, with appropriate support, Roma students are capable of completing their studies without positive discrimination. However, several of the principals mentioned that teachers do not differentiate between students in their teaching methods or assessments, treating all students equally regardless of background.

These principals said that this lack of differentiation may sometimes overlook the unique challenges faced by Roma students, such as language barriers or socio-economic disadvantages. Some of the respondents argued that a more individualized approach, rather than one-size-fits-all methods, could help to address the specific needs of Roma students more effectively. Others believed that positive discrimination, such as targeted support or additional resources, may not be necessary as long as the educational system continues to provide equal opportunities for all students. Despite this, there was recognition that Roma students might still face obstacles that could be mitigated with more tailored interventions. Overall, while Roma students can succeed within the existing educational framework, additional support could enhance their educational experience and outcomes.

According to the principals, teachers play a crucial role in fostering mutual acceptance between Roma and non-Roma students through the didactic methods employed in the classroom. They also highlighted the importance of joint programs and activities outside the classroom, such as collaborative projects or extracurricular events, to build relationships and promote understanding between students of different backgrounds. These initiatives, they noted, help students to learn to respect each other’s differences and cultures and work together in a positive environment. However, the principals acknowledged that the time-consuming nature of sensitization presents a significant challenge. They pointed out that changing students’ attitudes towards Roma students is not an immediate process and may take years to achieve meaningful results.

The principals emphasized the importance of taking a step-by-step approach. Teachers are encouraged to integrate sensitization efforts into their daily routines and lessons to gradually shift attitudes in a positive direction. This methodical approach is seen as essential in creating a school culture in which Roma students feel accepted and supported. Furthermore, the principals stressed the need for ongoing training and professional development to equip teachers with the tools and strategies necessary for effectively integrating Roma students. They believed that fostering an inclusive environment requires continuous effort from both teaching staff and the school community as a whole. The overall goal is to create a school culture in which all students, regardless of their background, can integrate seamlessly and successfully complete their studies.

The respondents’ opinions on the usefulness of training courses aimed at educating Roma students varied significantly. Six of the principals felt that the teachers were adequately prepared to teach Roma students, believing that they possessed the necessary knowledge and skills to educate them effectively. These principals emphasized that the teachers were already using a range of strategies to meet the needs of Roma students, including differentiated instruction and targeted support. They believed that additional training courses may not be essential, as the teachers were already equipped to handle the challenges of teaching Roma students.

However, two of the principals expressed uncertainty about the effectiveness of the current teacher preparation. These respondents could not decide on whether the teachers’ existing knowledge was sufficient for teaching Roma students and were unsure of what new opportunities or strategies training courses might offer. They suggested that while the teachers may have basic knowledge, specialized training could provide them with more specific insights into the cultural and educational challenges that Roma students face. They believed that targeted training courses could help the teachers refine their approaches and deepen their understanding of Roma students’ needs. Overall, there was a split opinion regarding whether additional training was needed, with some of the principals (four out of six) feeling confident in the teachers’ abilities, and others advocating for more specialized support to enhance Roma students’ educational experience.

According to the interviews, the principals generally viewed Roma student integration as part of their regular teaching duties rather than as an additional burden. Opinions were divided on whether targeted support was necessary, with some emphasizing equal treatment and others acknowledging the need for more individualized interventions. Most of the respondents believed that the teachers were sufficiently trained, but some suggested that additional specialized training could improve educational outcomes for Roma students. Emphasis was placed on fostering an inclusive school culture through structured sensitization and extracurricular activities. This structured coding provided a comprehensive understanding of how Hungarian-language secondary school principals perceive the education of Roma students.