1. Introduction to a Pedagogy of Hospitality

What does it mean to integrate a migrant person into ‘our’ culture? As professionals or volunteers who teach the national language to migrants, we must ask ourselves why: are we going to focus solely on the economic dimension, or are we willing to embrace broader social, cultural, and ethical perspectives? Do we conceive of language integration as a process of assimilation, where migrants must conform to a pre-existing norm? Or can we envision language teaching as a dialogue of knowledge, an intercultural process, or even an ethic of miscegenation?

Approaching language education from a pedagogy of hospitality requires us to rethink the teaching of the national language not as a unidirectional transmission of knowledge but as a process of decolonization—one that invites the narratives, experiences, culture, and daily life of migrants into the learning space. In this way, language learning becomes a dialogical translation, allowing newcomers to explore the host culture from a critical perspective. This perspective not only helps them navigate the complexities, codes, and symbols of their new environment but also enables them to recognise both the challenges and opportunities hidden within them.

Language is not merely about speaking; it is about thinking. Learning a new language involves more than mastering vocabulary and grammar—it is an act of meaning-making, a way of interpreting and reinterpreting the world. Through a pedagogy of hospitality, language education can move beyond mere functionality to become a transformative experience, fostering empowerment, mutual recognition, and true intercultural dialogue.

A pedagogy of hospitality that stems from diverse philosophical, educational, and ethical traditions that reflect on welcoming, otherness, and teaching as an act of openness to otherness. It draws on the concept of the ethics of hospitality inspired by

Lévinas (

1972) and

Derrida (

2000), both of whom emphasize responsibility toward others and unconditional openness to strangers. They point out that hospitality is not only an act of generosity but an ethical obligation. In the field of education, its influences are found in critical pedagogies (

Giroux, 1988;

McLaren, 1994), in the promotion of liberatory education based on dialogue and

Freire’s (

1970) awareness-raising, and in the recognition of the reality of others in contexts of exclusion to promote their empowerment. Furthermore, studies on intercultural education (

Kramsch, 1993;

Walsh, 2009;

Aguado, 2010) emphasize the need for pedagogical models that value linguistic and cultural diversity and avoid forced assimilation to foster coexistence and mutual respect. Hence,

UNESCO (

2016,

2019) promotes, based on the right to education, inclusive educational models for migrants and refugees where language teaching is not only a linguistic tool but a means for social integration and the exercise of citizenship (

García & Otheguy, 2020).

The ethics of hospitality, when it means the recognition of diversity, intercultural dialogue, the overcoming of us-them dichotomies when it supposes a weakening of strong and even murderous identities when it seeks to eliminate structures of domination and exclusion based on cultural, ethnic or linguistic differences (

Stavenhagen, 2001) when it is hosted between justice and equity, we find that the fundamental ingredient for this ethic is the mixture, the mestizaje (

Glissant, 1997;

Anzaldúa, 1999). A mestizaje that is not only a biological or cultural phenomenon, but also an ethical stance that recognizes the interdependence between different cultures, and identities, following the reflections of weak thought (

Vattimo & Zabala, 2012), is neither fixed nor homogeneous, it is a dynamic process that is enriched by interaction and exchange. The ethics of miscegenation that requires a pedagogy of hospitality is a philosophical and social approach that promotes the appreciation of cultural diversity and the encounter between different identities, highlighting the importance of dialogue, coexistence and the construction of shared knowledge from the mixture of knowledge, traditions and perspectives (

Fornet-Betancourt, 2005).

Before setting out to think about how to teach the national language to a migrant person, we must ask ourselves how we are going to relate to them. What is in his own language, in his memory, surely there is room for much more than in the suitcase in which he had to abstract all his past. Cultures are formed over millennia through the transmission of knowledge, values and practices (

Geertz, 1973). His legacy shapes each person from childhood, embedding a system of references to their familiar world. Yet, it now leaves them feeling like an outsider—disconnected, like Ulysses at the start of the Odyssey, sitting before us with a story to tell about a journey that has only just begun. As Stendhal said in Red and Black, in every life, there is a novel that deserves to be written. This idea is particularly relevant in the context of migration, where every person carries a unique story shaped by displacement, adaptation, and resilience. Behind the gaze of someone who does not understand us and whom we do not understand, there is not only a language barrier but a world of experiences, emotions, and aspirations waiting to be acknowledged. Language learning, therefore, is not just about acquiring communicative skills; it is about creating spaces for these stories to be heard. It is through this recognition that we can foster a migrant citizenship capable of participating—as a guest—in the commons, in the community, by connecting, engaging, and co-constructing new collective narratives (

Price, 2024).

Imagining the journey from an ethic to a pedagogy of hospitality in the teaching of the host language requires the art of conversation, that education be a dialogue of knowledge which, according to

De Sousa Santos (

2009), is a process of interaction between different forms of knowledge that seeks to overcome the hierarchy imposed by the epistemology that hosts. This approach promotes horizontal and respectful linguistic exchange. A dialogue that implies the recognition of linguistic diversity for the collective construction of knowledge based on respect, participation, and the recognition of the plurality of ways of inhabiting this small blue marble that we share (

Mignolo, 2000;

Castro-Gómez & Grosfoguel, 2007). In summary, philosophical hospitality materialized in the teaching of languages to migrants by transforming the classroom into a space of reception, recognition and construction of citizenship. Language becomes not only a means of communication but also a bridge for dignity and social inclusion.

Hospitality, from a historical and philosophical perspective, has been a central principle in many societies and traditions. Concepts such as Xenia in ancient Greece, hospitality in religious traditions (Christianity, Islam, Judaism), and the ethics of welcome in contemporary philosophy (

Derrida, 2000;

Lévinas, 1972) underline the moral obligation to receive and recognize the other. From this perspective, hospitality is not only a gesture of welcome but also an ethical and political commitment to the stranger. In the context of language teaching to immigrants, this philosophical vision of hospitality translates into pedagogical practices that go beyond instrumental language learning. Learning a language in a host country is not only a matter of communication, but also an act of integration, recognition, and empowerment. The Pedagogy of Hospitality proposes a teaching approach based on relationships of equality and dialogue, fostering a dialogue of knowledge where the experiences and native languages of immigrants are valued and respected. It creates safe and welcoming spaces so that language teaching is not merely a transmission of grammatical rules, but rather a building of trust where the identity and culture of immigrants are recognized (

Manfreda et al., 2024). The Pedagogy of Hospitality opposes the instrumental view of language as a mere economic tool, promoting an education that considers language as a human right and a path to community participation. It is a pedagogy that adapts teaching methods to the real needs of immigrants, considering their previous experiences, literacy levels, and specific challenges (

Green & Price, 2024).

2. Language Teaching from the Point of View of a Pedagogy of Hospitality: The Dialogical Construction of Migrant Citizenship

Pedagogy imagines education as the art of overcoming phobias with philias. Understanding the relationship between curiosity and danger leads us to ask why we call our home Earth when it should be called Ocean. Three parts of this planet are water, and the same proportion is in our own body. More important than the wheel was the discovery of swimming and navigation. Thanks to these discoveries we broke the limits set by our own genetics. We were not born to swim, as if our destiny was to remain on land. We didn’t stay on land, we took the plunge out of curiosity, because it is in our nature to learn to overcome our fears. At least a hundred thousand years ago the Neanderthals of the Grotta dei Moscerini dived to depths of five metres to collect clams. Swimming and then sailing allowed us to get to know the world and to recognise each other. From the sharing of dangers arose the laws of hospitality, and from shared passions, compassion was born. Xenia, understood as the law of hospitality in Ancient Greece, established standards of welcome and respect between hosts and foreigners, a principle documented in Homeric literature and analyzed by classical studies (

Benveniste, 1969).

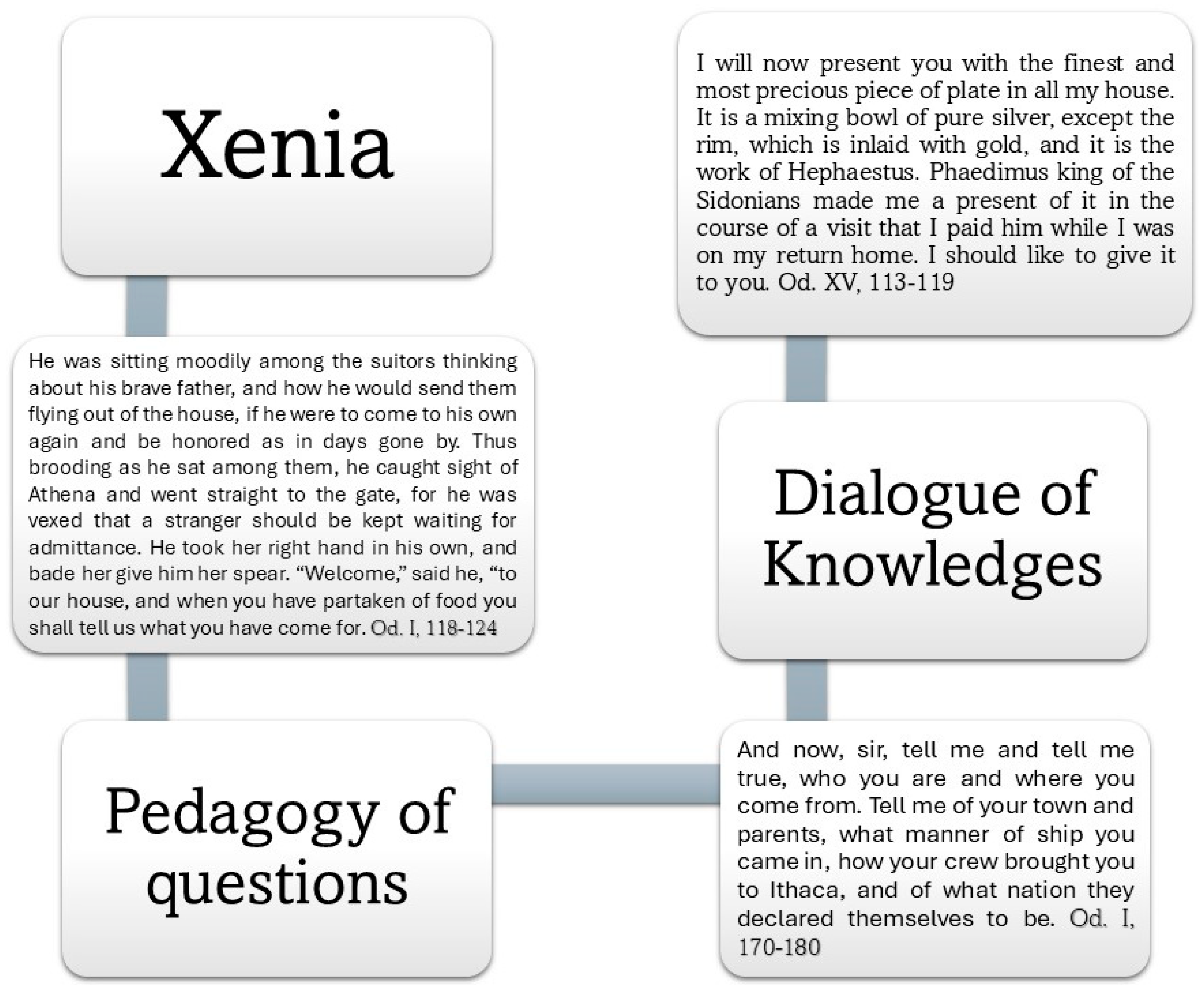

Hospitality or a feeling of welcome among peoples who shared the fear of shipwreck, that ancestral putting oneself in the place of the other that is reflected in the Odyssey or in Homer’s Iliad. A custom shared by all the cultures that inhabit the memory of the place we call Europe and which, without the same borders, has become a ‘democratic’ community due to migratory movements and the influence of a myriad of cultures. Hospitality was called Xenia, a bond of hospitality, and friendship between guests. Its etymology derives from the noun

xénos which means foreigner, guest. In other words, xenophobia does not only mean hatred of the foreigner, but it is also an antagonistic position towards hospitality. Xenia (

Figure 1) was so important that, even though it was not institutionally regularised, it was recorded in a ritual with a series of clearly differentiated steps that are reflected in the following songs of the Odyssey: first the welcome; the roof and the food, second the interest in the other, a kind of pedagogy of questions (

Brass et al., 1985) and a third step the exchange of gifts as a dialogue of knowledge (

Velasquez-Pérez et al., 2019).

As professionals or volunteers who are going to play a leading role in hospitality by teaching the national language, we need to ask ourselves and ask questions, in the way Socrates founded his maieutic. To translate interculturally, i.e., to bring the Xenia—which founded Europe as a home for migrant cultures—into the present through a diatopic hermeneutics, so that we plan the teaching of the national language through the phases of the ritual of hospitality—as vertices of a pedagogy of hospitality—(

Kearney & Fitzpatrick, 2021). We call diatopic hermeneutics the need to understand the other without if he or she has the same self-knowledge and basic knowledge as us. We assume that we must overcome a distance, within a broad tradition, between two human topoi, between two places of understanding the world, and between two or more cultures that have not developed their models of understanding between them (

Panikkar, 2007).

Xenia, from this diatopic hermeneutic, means a cultural exchange through the linguistic teaching-learning process of reception. Making migrants feel at home requires professionals and volunteers to show respect and curiosity toward their native language, culture, experiences, and identity.

Freire (

1970) emphasizes that genuine dialogue, based on mutual learning and respect, is essential for fostering meaningful relationships and empowering marginalized communities. Similarly,

Vygotsky (

1986) highlights the role of language in shaping thought and identity, stressing that recognizing migrants’ linguistic backgrounds facilitates both personal and social integration.

Cummins (

2000) reinforces this idea by demonstrating that valuing a person’s first language enhances self-esteem and academic success in second-language learning. Additionally,

Derrida (

2000) challenges traditional notions of hospitality, arguing that true hospitality means embracing the “other” without conditions, recognizing their language and culture not as barriers but as enriching contributions. By adopting these perspectives, professionals and volunteers can go beyond mere tolerance, fostering spaces where migrants feel genuinely welcomed, respected, and included.

But in addition to a critical respect for the migrating culture, there is a necessary critical review of our own culture, the one that hosts it. What elements of our cultures are we going to convey through the teaching of the national language? Choosing content from a critical perspective implies a questioning of our society, not only to offer significant contributions from the different disciplines that make up our knowledge but also to warn about the menaces that arise from our inequalities and miseries. Offering the complexity of hosting and, at the same time, empowering the person who arrives. To design a curriculum so that the teaching of the national language becomes an epistemology of consequences that generates knowledge as an intervention, an indispensable step towards the construction of migrant citizenship (

González Pérez & González Novoa, 2021).

The political nature of education as a process of transformation of people for the transformation of the world requires a brief review of what is necessary—as a

conditio sine qua non—for democracy, i.e., citizenship. The construct of citizenship that emerges in Greece between Homer and Socrates is configured on three points: negative freedoms that have to do with those aspects that the State must respect and protect, positive freedoms that refer to the duty of each person to participate politically in the community, in the commons, and social rights that guarantee a dignified life for all (

Figure 2).

The challenge as professionals or volunteers is also to understand the evolution of the concept of citizenship from the Greek model to the liberal model of the American and French revolution, passing through the socialist proposals of community citizenship, the republican version, differentiated citizenship, multicultural and post-national citizenship that make up the European Union, in order to understand that all our versions throughout history are based on two elements that make it difficult to be welcomed as a host (

Bellamy, 2015).

The ius solis and

ius sanguinis—which underpin our models of citizenship (

Figure 3)—require being born in a specific territory or being the child of parents who are from a specific territory (

Banerjee & Suchowlansky, 2013).

Migrant citizens need to be educated, through language teaching, to understand the elements of the host culture that hinder intercultural processes. If education, specifically the teaching-learning of the host language, does not serve to build citizenship, then it is a process of acculturation, subjugation, segregation, a colonisation of knowledge that does not want the newcomer to participate except as a stranger, with limited rights and duties, something like the free version of the applications that are multiplying on the Internet (

González Novoa et al., 2024).

Constructing migrant citizenship by educating and learning requires an ethic of miscegenation. Strong, national, impermeable identities do not mix, and the pedagogy of hospitality needs to blend, making migrant protagonists and participants in the teaching-learning process of the host language through their words, their memory, their experience, and their culture. This is a Copernican shift like what Rousseau proposed in relation to the teacher and the child who needs, following the ritual of Xenia, a pedagogy of questions and a dialogue of knowledge.

What do we mean by dialogue of knowledge? Environmental rationality links us to an intercultural dialogical relationship, starting from what

Leff (

2004) proposed. We need to introduce elements of the pedagogy of questions from Socrates to Freire, thus generating an entrance porch, a hallway where to promote a substantial exchange of cultures through words, because we think words and teaching also imply teaching to think of another way of inhabiting the world.

It implies a dialogical relationship of exchange, in both directions, on the part of the professional or volunteer to offer significant contents, elements of the host culture that represent it in its complexity, that offer its splendour and its contradictions, that result in a vivid portrait capable of containing the ethical and the aesthetic in balance. What contents are we talking about? It is a question of widening the narrow corridor of useful knowledge to create a space where incalculable knowledge, excluded by the techno-scientific pact that colonises knowledge, can offer hospitable epistemologies, where otherness can be recognised, feel part of it, belong. It is not up to us to decide which ones, surely, we share many of these references that make up our cultural canon, from the arts to the sciences, we can compose a curriculum that invites migrants to learn the new language as a door to the memories that tell us about sharing the world (

Vila, 2014). A case in point is the vital and then written work of Nuccio Ordine (a teacher who read short texts of the classics in any subject with the intention of making students discover the particularity of their existence within those works which, the teacher sighs, he would one day read in order to live better and feel part of something greater than the self).

We skipped, in the last paragraphs, the second vertex which is a fundamental condition for the third, the dialogue of knowledge. The strategy of the inn, which is reflected in the beginnings of the Decameron and in the Canterbury Tales, typical of migrant cultures, is shaped as a pedagogy of questions. We must ask ourselves what it means to ask questions. To underline that Freire intuited curiosity in the body of a question and that knowledge seemed to him to come from the art of questioning (

Figure 4).

To ask is to want to understand, different from understanding—as Ortega y Gasset thought -, to understand is to want to know the other person, an express desire to break down prejudices, to break down archetypes, to dismantle myths and, with the generosity of someone who feels like a guest in the world, to invite the migrant person to learn the new language from their words and their narratives through questions. What do we know about the migrants who need to learn the language of the host country? How many writers have we read? Do we know about their representative works of art? Do we know about their beliefs or their daily lives? Do we feel we can learn from those who come to learn? What can we learn by teaching the national language to those who are learning it?

To ask ourselves questions and to ask questions is to share a place of passage and encounter, like the architecture of hospitality, to exchange cultures while learning words. And it is important because

traduttore and

traditore, words that do not mean the same thing, have contexts that must be narrated and listened to. Does dignified life mean the same thing here as there? Do we speak of the same thing when we pronounce the words friendship, family, wealth, happiness, and fear? Each word, with each experience, is filled with unique meanings that allow for unique encounters, teaching the language to the migrant should be an event where the past is recognised in the present that hosts it. A sort of migrant narratives that promote an intercultural translation of knowledge (

Olk, 2009;

Sepúlveda Varas & Valderrama Aguayo, 2023).

The dialogue of knowledge, as the third vertex of a pedagogy of hospitality, means being cultural ambassadors of welcome, listeners, in the application of Xenia, of the migrant’s story; in other words, questioners who learn the other in order to be able to teach not mine, but ours, and also to travel through all the knowledge, the useful and the useless, so that all identities are found in the words they learn. When we ask at the beginning, ‘What travels in silence?’ we project in the professional or volunteer the seed of curiosity to understand who arrives terrified, without family ties, without knowledge of customs, symbols, rules, unprotected and vulnerable, and not to succumb to paternalism, to put ourselves in the other’s shoes without forgetting that they are not ours in order to promote an education linked to this model of migrant citizenship that allows them to know their rights, their duties and commit themselves to participate in the common, in the community (

González Novoa & Perera Méndez, 2023). As Aristotle stated, the common; the

koinos, is produced when citizens deliberate together to determine what is good for the community, and what is right to do, living together does not mean grazing together, nor does it mean putting everything in common, but rather putting words and thoughts in common, it means producing, through deliberation, similar customs and rules of coexistence that apply to all those who inhabit this tiny blue marble floating in the ether. Can we imagine teaching the national language to a migrant person in terms of the common?

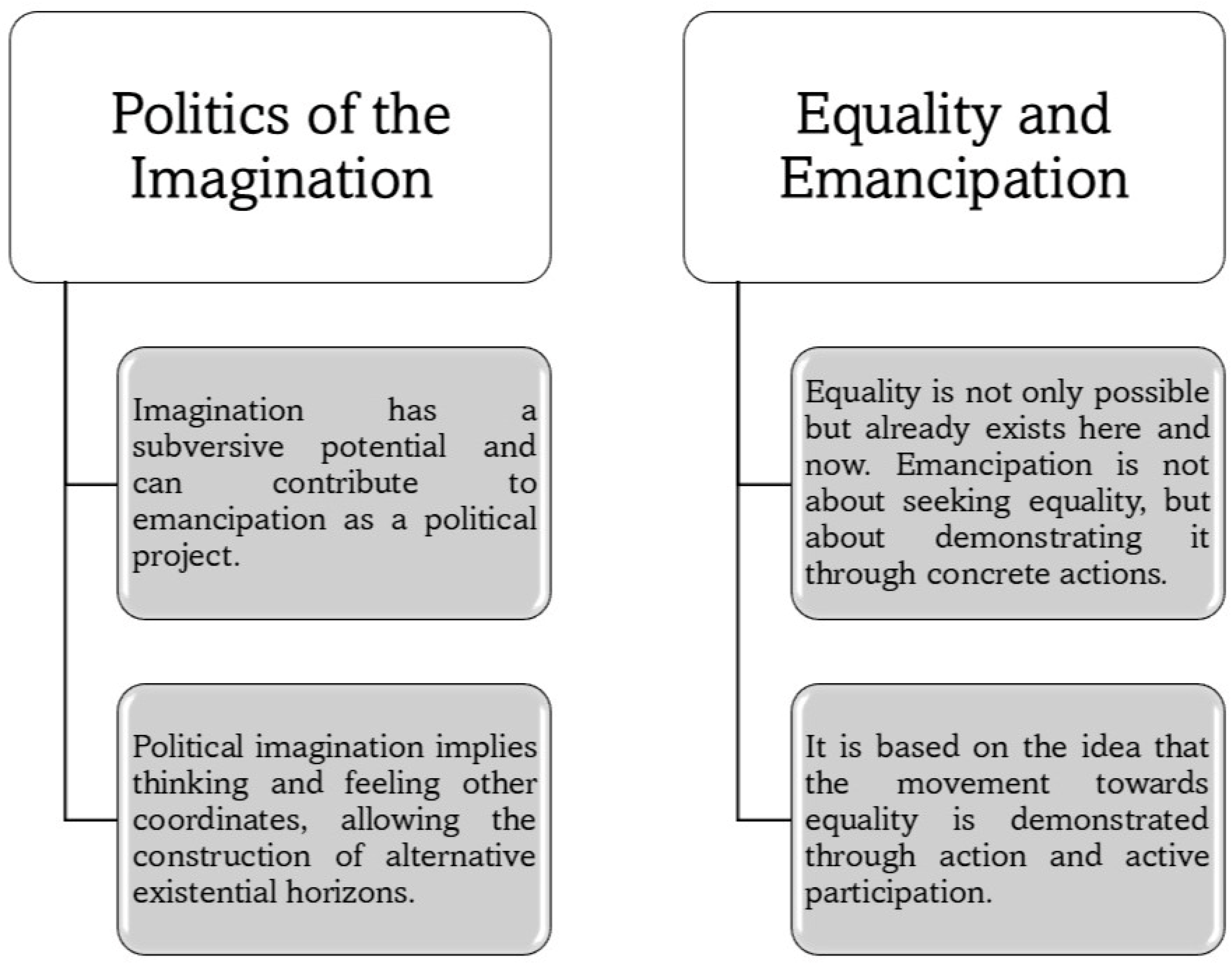

Let us recapitulate: starting from that liquid law that founded the ritual of hospitality; Xenia, we need a pedagogy of questions that invite us to a dialogue of knowledge with the express will to establish, in the processes of teaching and learning the host language by migrants, an ethics of miscegenation that builds models of migrant citizenship and, for this, we need what Jacques Rancière argued, that the political imagination is a possibility of the world that questions the evidence of the given reality, an imagination that favours emancipatory powers by allowing us to think and feel other coordinates beyond the logics of domination (

Castillo, 2021).

Emancipatory political imagination (

Figure 5) is a concept that refers to the ability to imagine and conceive of a world different from the present one, one that challenges power structures and seeks the liberation of oppressed people. This idea suggests that imagination is not only creative but also political, as it can challenge established norms and open space for new possibilities. In other words, political imagination allows us to think beyond the limits imposed by general theories and universal ideas and invites us to consider transformative alternatives for society (

Anastasova, 2023). By imagining an emancipated world, we can transcend constraints and work towards a more hopeful and liberating existential horizon.

An emancipatory political imaginary that we cannot conceive, no longer or with great difficulty, of a narcissistic, in our case, Eurocentric or Occidentalist, point of view. We therefore need to learn to ask hard questions such as: why are there so many different principles on human dignity and social justice, all supposedly unique, but often contradictory, or what degree of coherence should be demanded between the principles, whatever they may be, and the practices that take place in their name? Or is the process of secularisation considered one of the most distinctive achievements of occidental modernity irreversible? What, if anything, could religion contribute to social emancipation? Or is the concept of nature as separate from society, so embedded in Western thinking, sustainable in the long run? Or is there room for utopia in our world? (

Santos, 2019) Questions that involve us beyond our particularities, whatever they may be, that summons us to play a leading role in the process of teaching a language, to play a leading role in a dialogue of knowledge where we need to break with the role of teacher-host and embody the spirit of the guest who inhabits it, for example, in Italo Calvino’s Castle of Crossed Destinies, wherein a common space there is an exchange of rationalities and emotionalities, of migratory narratives that rewrite with many hands and many voices a present with the intention of a future (

De Sousa-Ferreira & Alonso Riveiro, 2023).

The astronauts who saw our common home for the first time contemplated a fragile blue marble floating in the ether and felt that all the conflicts we face on a daily basis, all those apparent differences of language, skin, and culture, are made invisible by the perspective that this marble is the only home in which we can live in the present and imagine a future. A limited and fragile space that needs our care. To think of education of any kind without this change of perspective only seems to feed what we understand as suicidal capitalism. The challenge to build migrant citizenships that are neither ascribed to nor contained by physical and cultural borders requires learning a critical language that dialogues and problematises the realities that are in transit, from an intercultural translation of those words that summon us towards an ecology of knowledge. A pedagogy of hospitality underpinned by an ethics of miscegenation and an emancipatory politics that imagines migrants as potential friends, not potential enemies, willing and available to participate with intersubjective responsibility and to engage in the care of what Carl Sagan fondly called the Pale Blue Dot. An overview effect to exchange the good life or capitalist binge for the art of good living, or better still, good coexistence (

Voski, 2020).

“Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves. The Earth is the only world known so far to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment the Earth is where we make our stand. It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known”.

3. Language Rights and Human Rights: International Commitments to the Educational Rights of (Adult) Refugees and Migrants

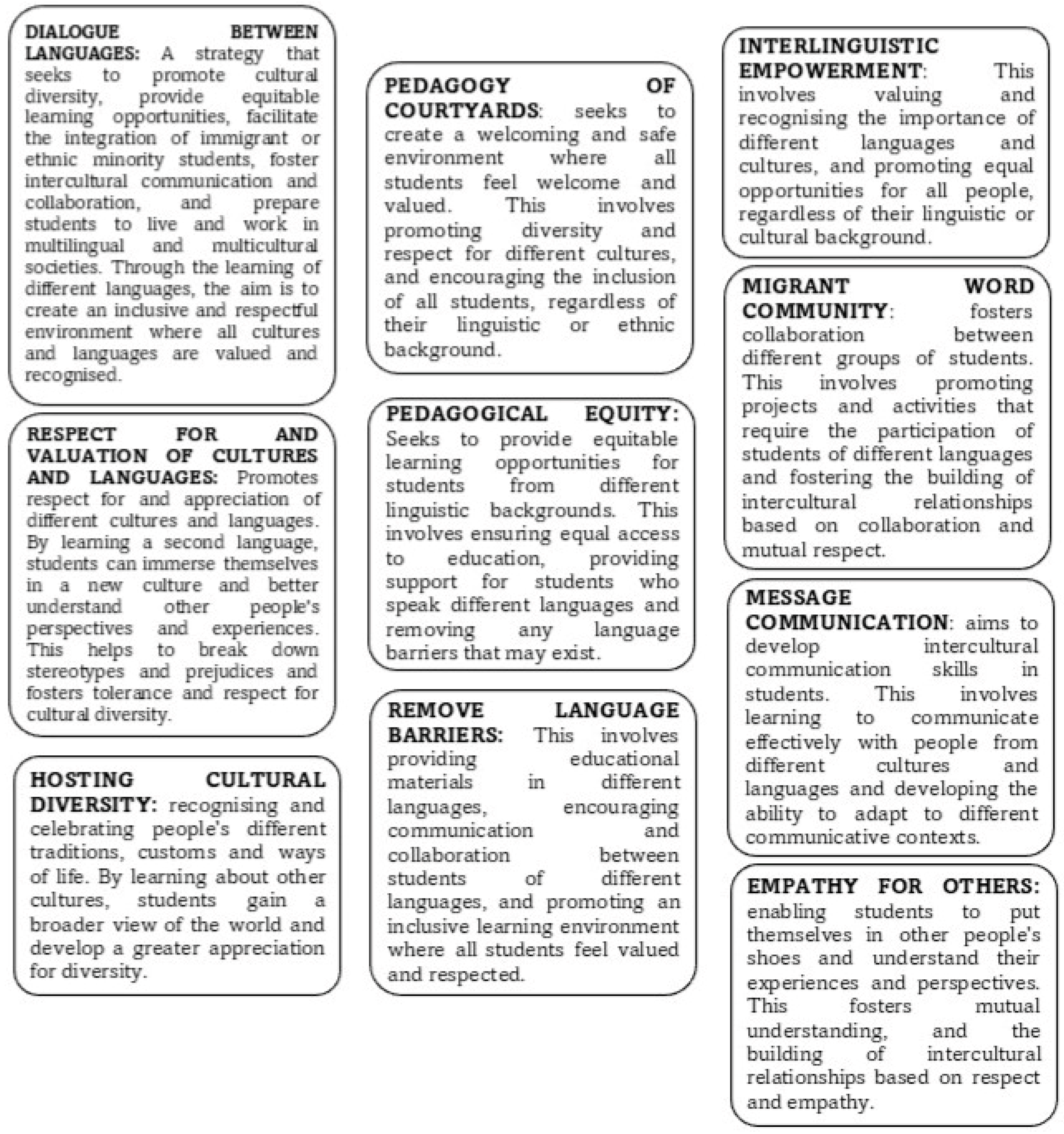

How can teaching the host language contribute to empowering immigrants to participate in society, promoting integration, intercultural dialogue, and building a more cohesive, just, and supportive community? Achieving meaningful intercultural dialogue requires a combination of linguistic sophistication, intercultural competence, and an understanding of different modes of communication. Key strategies to achieve this include fostering plurilingual competence by leveraging students’ linguistic repertoires and promoting translanguaging practices (

García & Otheguy, 2020), as well as creating spaces where students can move freely between languages without rigid restrictions. It is also important to develop intercultural sensitivity by explicitly teaching the pragmatic norms and cultural frameworks that influence communication (

Kramsch, 1993) and reflecting on one’s own linguistic and cultural biases to avoid imposing a monolingual or ethnocentric view. Using multimodal texts, such as images, gestures, and sounds, can enrich communication as these resources complement verbal expression and help construct meaning in multilingual contexts. Finally, designing authentic interaction activities, such as debates and collaborative projects, allows students to use their linguistic and cultural repertoires, while also exposing them to authentic materials in various languages and registers to improve their communicative competence.

Migration in Europe has been a central issue in recent decades, driven by conflict, economic inequalities, and climate change. This constant flow of people presents a series of challenges and opportunities that require an approach based on human rights, hospitality, and respect for human dignity, and all that this represents. The human rights framework seeks to protect migrants, but its effective implementation is influenced by the complexity of the legal system that regulates these rights. In this context, language rights and the promotion of interculturality play a crucial role in the daily life of every migrant (

UNESCO, 2005). While in theory they promote a vision of language rights and interculturality as pillars of inclusion and equity, in practice we encounter barriers that prevent their full realization. To close this gap, it is necessary to implement more effective policies, train teachers with intercultural awareness, and promote a change of mentality in society that values all languages and cultures equally.

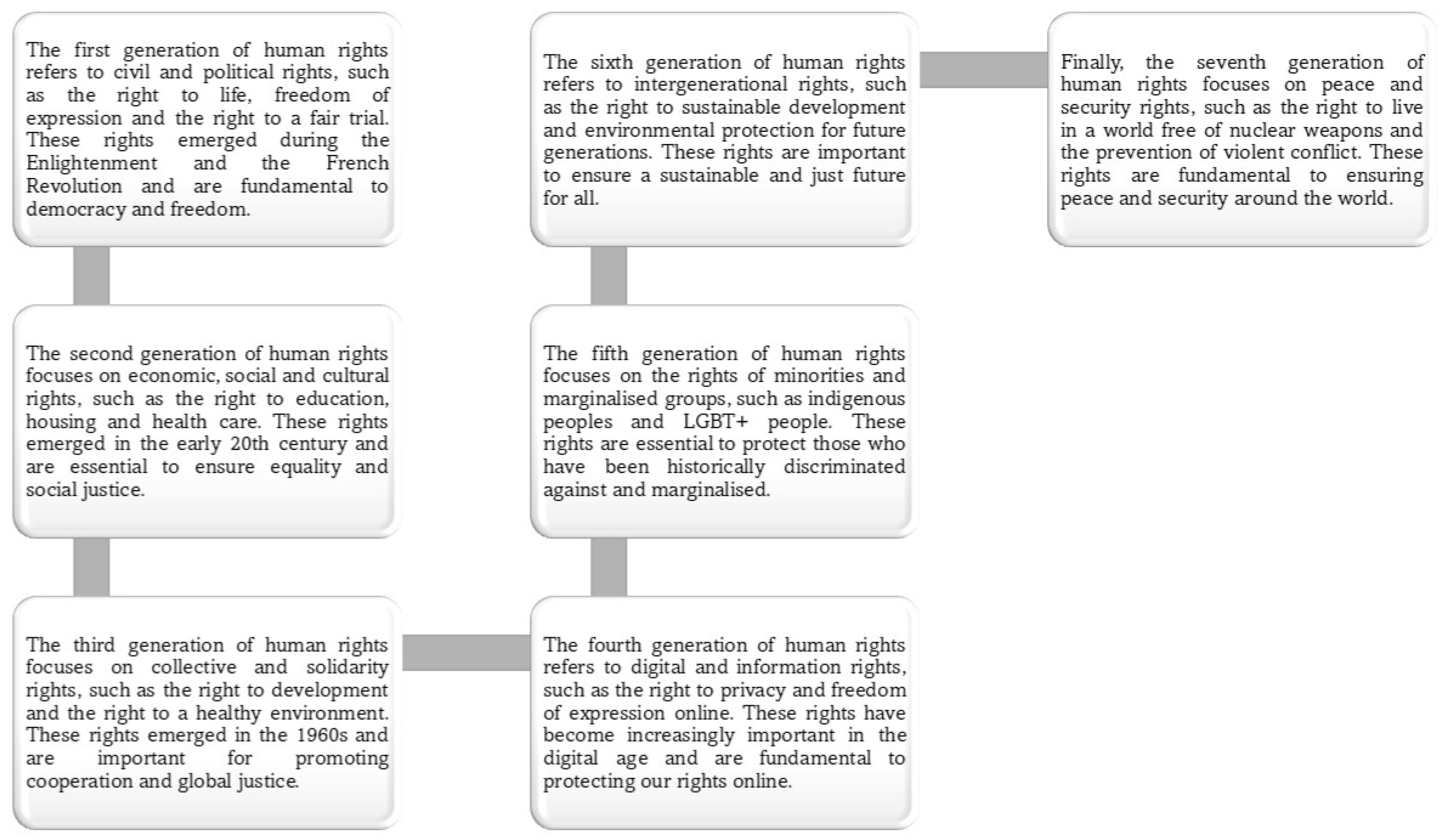

Human rights belong to everyone, regardless of nationality or migration status. Documents like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention on Migrant Workers’ Rights highlight the dignity and respect all migrants should receive, emphasizing basic rights such as life, security, non-discrimination, and equality before the law (

Figure 6).

Global legal frameworks have evolved into a network of treaties and agreements aiming for common rules and cooperation between nations. However, their success depends on the political will of democratic systems.

It’s important to distinguish human rights from legal systems. Human rights are universal and unchanging (

Figure 7), while legal systems are human-made and can change based on political decisions. Legal systems decide which rights are prioritized and set limits on their application (

OHCHR, 2017;

Domaradzki et al., 2019).

This process recognises legacies of more authoritarian or absolute models, but since the installation of democratic structures, debate and the formulation of negotiations and consensus on what rights to include and when to include them has developed. However, this does not mean that all rights are “born” with their formal recognition, especially those linked to human dignity, which are inherent—natural—to human existence itself.

Modernity, with its ideals of “liberty, equality, and fraternity” promoted during the Enlightenment and exemplified in events like the French Revolution, aimed to create just, equitable, and rational societies. These principles led to the development of universal human rights and democratic systems designed to protect individual rights and ensure citizen participation. However, this promise remains largely unfulfilled.

While technological and scientific advancements have been significant, power structures and social inequalities persist and, in some cases, have worsened. Global capitalism and globalization have led to wealth concentration, leaving many in poverty and challenging the ideals of equality and social justice. Political systems often prioritize economic stability and national security over social justice, resulting in policies that marginalize vulnerable groups and maintain structural inequalities.

This situation reflects a gap between the universal principles of modernity and the reality we face. Ongoing conflicts, discrimination, migration crises, and climate change highlight the limits of modernity’s promises. The ideals of modernity remain aspirational, emphasizing the need to reform social, political, and economic systems to bridge the gap between theory and practice (

Cloquell-Lozano & Novella-García, 2022).

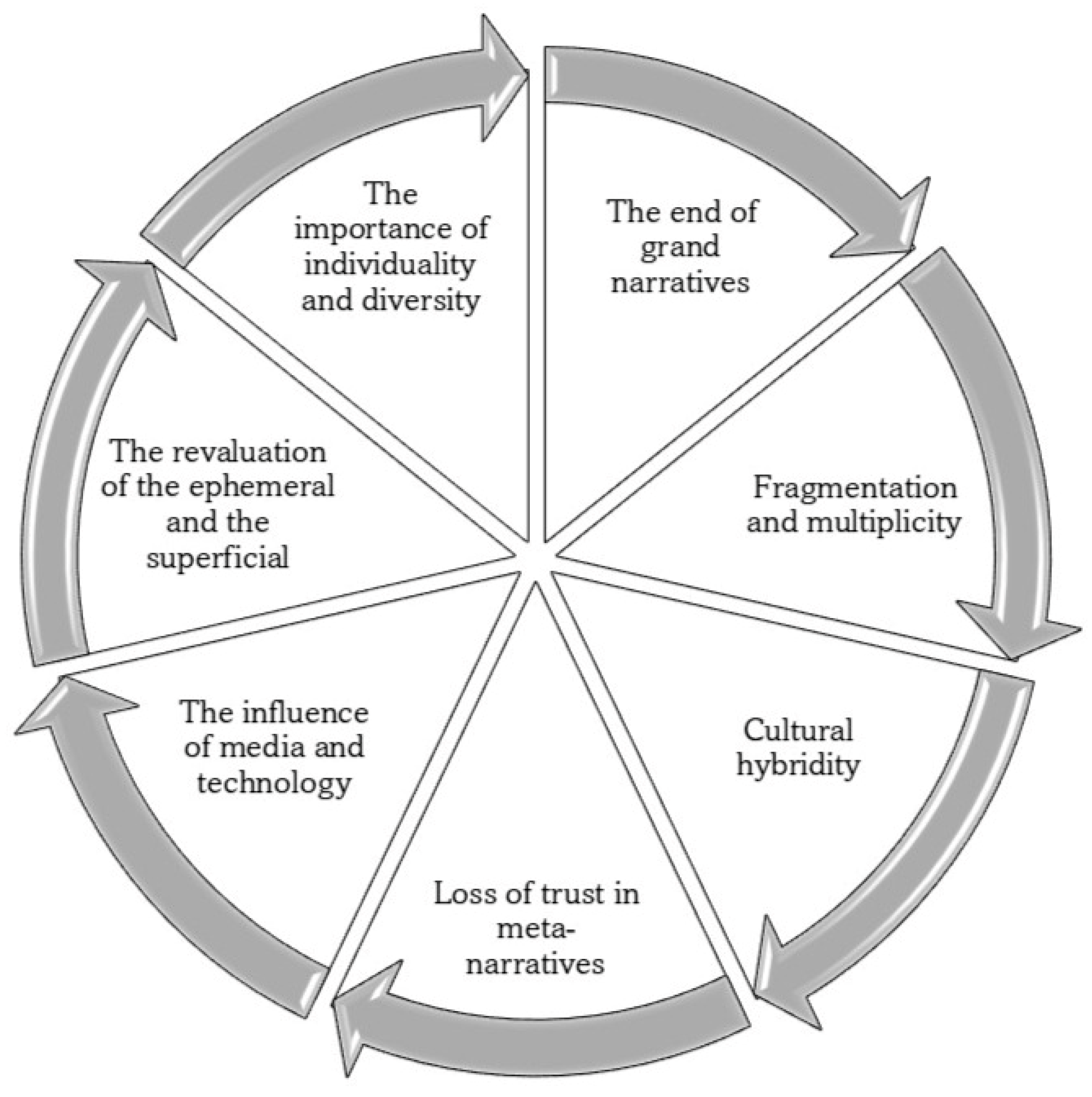

In the postmodern era (

Figure 8), shaped by globalization and hyper-connectivity, we face the challenge of turning the promise of a more inclusive society into reality. To achieve this, institutions must adapt to an increasingly interdependent world. International cooperation and political will are essential to transforming legal frameworks into concrete actions that guarantee human rights for all.

In this context, language teaching plays a crucial role. It not only helps individuals understand legal and social norms but also empowers them to defend their own rights and those of others. Learning a language provides access to essential information about healthcare, education, employment, and social services. It also facilitates communication with neighbours, colleagues, teachers, and local authorities, fostering social and cultural integration. Furthermore, it increases opportunities for civic and political participation, enables individuals to negotiate working conditions, and improves access to legal services.

However, effective communication (

Figure 9) goes beyond learning a language. Decision-making, critical thinking, and the defense of one’s rights require more than just mastering linguistic codes. Understanding and using a language is only the first step—what truly matters is enabling individuals to express themselves, actively participate in society, and build meaningful connections that strengthen social cohesion (

MICIC, 2016;

Brown et al., 2021).

What has already been pointed out in previous sections, and what will continue to be pointed out in subsequent sections, is developed here. The importance of understanding teaching processes as a bidirectional, even multidirectional reality; diverse by nature and therefore in need of a share born in subjectivity. This requires questions, spaces, notions that welcome ways of life, and not only give presentations of a single model. It requires social openness to interculturality, which overcomes the idea of static grouping of cultures, of mere tolerances.

“The two principles of justice are as follows: a. Each person has an equal right to demand a fully appropriate scheme of basic and equal rights and liberties, a scheme which is compatible with the same scheme for all; (…) b. Social and economic inequalities are justified only by two conditions: first, they will be connected with positions and offices open to all (…); second, these positions and offices must be exercised to the maximum benefit of the least privileged members of society”.

From these lines, it is understood that it is possible to overcome this duality by adopting a holistic and systemic approach that recognises the interconnection between individual action and social change at the collective level. Starting from critical reflection on teaching practice, educators should be encouraged to reflect critically on their role in promoting social change and equity in education. This involves questioning assumptions, examining implicit biases and constantly seeking ways to improve and adapt teaching practice to more effectively address social and cultural challenges. It is distilling the data that shapes the dominant narrative from real and current information. It is about integrating collective action into the curriculum so that, from a communal vision of the same class group, the identification and tackling of palpable social and community problems is jointly addressed. This not only fosters the development of collaborative and teamwork skills but also teaches students the importance of collective action for meaningful change.

Gradually, educational action will build partnerships with the host community (community organisations, activist groups and other change agents) to identify needs and opportunities for joint action. This can help to extend the impact of teaching and learning beyond the classroom and create meaningful connections between the school and the community. It is to use a strategy from partnership with the immediate to the collective and common. It is to create a community that influences, creates and supports personal and social transformation. It starts with the recognition that social change (of opinion, action, politics, etc.) begins at the individual level, in this case, and with educators and their students. Of course, this strategic objective must fit in with an approach to language teaching based on sensitivity to the linguistic and cultural diversity of each immigrant and underline some important aspects from a didactic point of view, but the fundamentals cannot be lost sight of (

Lorenz et al., 2021).

In the end, we have a personal and collective goal while combining a multitude of subjective and singular facts that make up a classroom, ten classrooms, a hundred classrooms and a lot of migrants belonging to a shared time and space to make a common future (

WCED, 1987).

“The demand for recognition in these latter cases is given urgency by the supposed links between recognition and identity, where this latter term designates something like a person’s understanding of who they are, of their fundamental defining characteristics as a human being. The thesis is that our identity is partly shaped by recognition or its absence, often by the misrecognition of others, and so a person or group of people can suffer real damage, real distortion, if the people or society around them mirror back to them a confining or demeaning or contemptible picture of themselves. Nonrecognition or misrecognition can inflict harm, can be a form of oppression, imprisoning someone in a false, distorted, and reduced mode of being”.

Linguistic rights are a fundamental aspect of human rights, as they are closely related to cultural identity, social inclusion and equal opportunities. However, the boundaries of these rights for groups that have migrated to another territory are blurred and often depend on the “particular” rights of the host society. The host’s fear of losing an identity is pitted against the fear of losing the memory of those who have moved. It is an unequal struggle that has a very difficult outcome, if not a solution.

We almost always focus on the teaching of the mother tongue as a facilitator of the integration of migrants into the territory, generating a real acculturation of migrants. Often this language training is not even bilingual, much less in the recognition of minority or foreign languages, which would be “typical” strategies of a state that protects the languages existing in its territories (

Council of Europe, 2024).

“Recognition’ has become a key word of our time. A venerable category of Hegelian philosophy, recently revived by political theorists, this notion is proving central to work to conceptualise current debates about identity and difference. Whether the issue is indigenous land claims, carework, homosexual marriage or Muslim headscarves, moral philosophers increasingly use the term ’recognition’ to uncover the normative bases of political claims”.

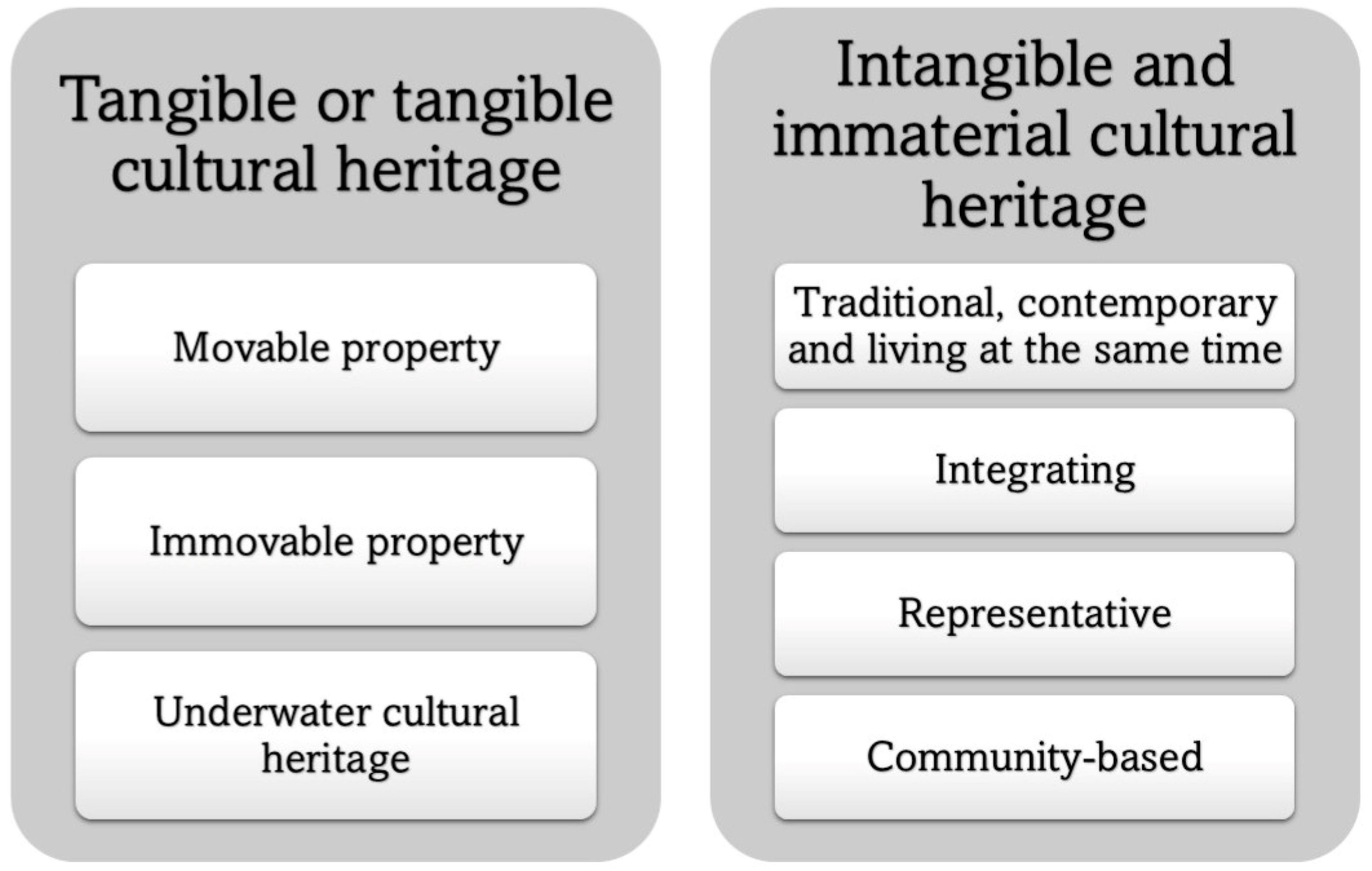

The preservation, development and expression of cultural and linguistic reality and heritage is, in turn, the expression and maintenance of one’s own identity (

Figure 10). The language teaching of the host country language should not only facilitate integration into the new society but also respect and value their previous cultural and linguistic identity (

Errington, 2008). Bidirectional language learning acknowledges that the integration process is not a one-way process but involves a dynamic interaction between migrants and the host society. Migrants bring their unique experiences, knowledge and perspectives, thus enhancing the cultural and linguistic fabric of the host community. At the same time, learning the language of the host country empowers migrants to participate fully in the social, economic and political life of their new community, thus exercising their right to self-determination in an intercultural context (

Lynch, 2023).

To close this section, we come to the practical dilemma of National Language teaching the crucial role played by the teacher and how essential it is for the development of each person to recognise their mother tongue. It is a continuous pulse between the promotion of integration in society, access to educational and employment opportunities and the generation of a cultural identity of one’s own, shaping integral persons and ratified by endless legislation and international treaties.

Is it to present the typical programming of bilingual education and its benefits but also its deficits when the culture “left behind” is seen as surpassed, both by cultural aspects of the destination, as well as by the personal histories of the people?

In the end, teachers focus on improving “digital competence” and focus on a multitude of pedagogical and didactic strategies that often, even when they achieve an inclusive, respectful and safe environment, fail to highlight the value of linguistic diversity due to the pressure of an environment that is always hostile to foreigners.

The very lack of a home where the direct hostility of the environment is dissipated in close relationships, spaces of respite from total immersion while not opening places in educational institutions to allow and even encourage the use of the mother tongue makes the work of migrants and their teachers a difficult mountain to climb (

Kung et al., 2013).

Spaces need to be found in which the challenges faced by teachers, such as lack of training in intercultural education, limited resources, or restrictive education policies, can be discussed. Spaces in which to complain and at the same time explore opportunities to improve language education, such as in-service teacher training, the development of inclusive teaching materials and collaboration with language communities (

Young, 2024;

Gerlach, 2021).

4. From the Pedagogy of Hospitality to Critical Teaching of the National Language

Given the fundamental role of teachers in language teaching, it is important to ask: what type of training should they receive to address both the pedagogical aspects and the cultural and linguistic challenges of intercultural education? This question as a space for reflection invites us to look into the mirror of the other, to imagine language learning as a vehicle of singular transformation—emancipation—and plural—alignment with the common good. Recalling that the Greeks had two words in this regard, for the person who aligns his or her singular emancipation process with the common good they called politikos, and for the person who prioritises his or her personal interest over the community they called idiotas. The singular transformation and its alignment with the common good -koinos- calls us to think about how the teaching and learning of a language can mean an intercultural projection, political co-responsibility and social commitment, and an openness to intercultural synergies in relation to diversity. What selection of resources and/or activities and experiences of meaningful learning do we need? What do we understand by meaningful learning? What contents do we imagine to be meaningful for critical training and awareness of the language teacher? Following the narrative of Ordine in L’utilità dell’inutile, if aliens were to arrive at this little blue marble floating in the universe, attached to the principle of utility, perhaps we would present humanity from the urinal but, surely, other creations come to mind that, equally, do not represent it with greater dignity.

What should education be for? Any process of education (and the process of teaching languages to immigrant populations is one) always involves a project of subjectivation, not just learning. Learning is something that always happens, per se, in any human being: if these migrant populations were left alone in the host national contexts, would they not end up learning the rudiments of the language, even if they did not want to?

Therefore, what is important, when we consider undertaking any educational process, is not the question of how to promote more and better certain learning (in this case, learning the language), but how to contribute to this process of subjectivation that calls for education (how to become a subject, an agent of oneself, within the framework of the host culture and state).

This is neither the time nor the place to delve into the theorization of the conceptual universe underlying the previous statements. Suffice it to note that this project of subjectivation, which requires education, is particularly relevant in the context of language teaching for migrants, as it seeks to empower learners to exercise the freedom inherent in their human dignity. As

Rühlmann (

2023) suggests, subjectivation is a dynamic process through which individuals shape themselves while actively interacting with the social structures that define their existence. In this sense, language education plays a fundamental role in fostering critical agency among migrants, enabling them not only to acquire linguistic skills but also to navigate and challenge the discourses that shape their identities, opportunities, and social integration. Through language, migrants can assert their voices, participate in society, and claim their rights, transforming language learning into a key tool for personal and collective empowerment.

Managing one’s own freedom is a complex aspiration that has essentially been redefined in two ways: the freedom to be able to be and the freedom to want to be.

Berlin (

1958) explains this through his distinction between negative liberty, which is the absence of external obstacles, and positive liberty, which is the ability to shape one’s own life. In this sense, true freedom requires not only the removal of barriers but also the power to make one’s own decisions. The freedom to be refers to having the necessary resources and opportunities to live a dignified life, such as access to education, healthcare, and financial stability. The freedom to want to be, on the other hand, relates to the ability to make personal choices and pursue aspirations without external constraints, emphasizing autonomy and self-determination.

For instance, in the context of language education, a student has the freedom to have access to quality language learning resources, qualified teachers, and an inclusive learning environment. Meanwhile, a student with the freedom to want to be can choose which language to learn based on personal interest or career aspirations rather than being forced by economic or societal pressures.

The freedom to be implies, among other things, having the means of life that facilitate access to options and alternatives. This always involves a more egalitarian distribution of material goods that enable subsistence and well-being, equality in recognition, and equality in the possibility of participating in community decisions. In short, it brings us back to the idea of equality and, behind it, to the pursuit of social justice.

The role of education understood then as a lever of social justice (a political tool), is to contribute to developing in learners the capacities (competencies) that enable them to access, within the framework of complex societies, the distribution of goods (mainly through a qualification that allows access to the labour market) and a homologated status of citizenship (mainly through socialisation based on the recognition of respective identities and an understanding of the structures of citizen participation). By integrating these principles into language education, learners are not only acquiring linguistic skills but also gaining the freedom to navigate and shape their social realities in an equitable and autonomous manner (

Hossain, 2024).

The freedom to want to be is more related to processes of ethical self-construction. It implies having constructed oneself not only with a determined, freely chosen identity but having done so within the framework of a problematising analysis of the legitimate moral options available and having internalised those that are considered most appropriate to serve one’s own ends and the common good. This second aspect of what emancipatory development implies is, perhaps, the most educational and, beyond educational policies, looks directly at the way in which the educational relationships that allow each learner to become a subject are shaped and developed.

Education is a process of ethical self-construction and emancipation, influenced by the cultural context and guided by an educator (

Southwell & Depaepe, 2019). The ultimate result of this process should be the transformation of the subjects being educated in such a way that they are able to define their own good (i.e., ethically oriented) life project, aligned with the common good (

UNESCO, 2015).

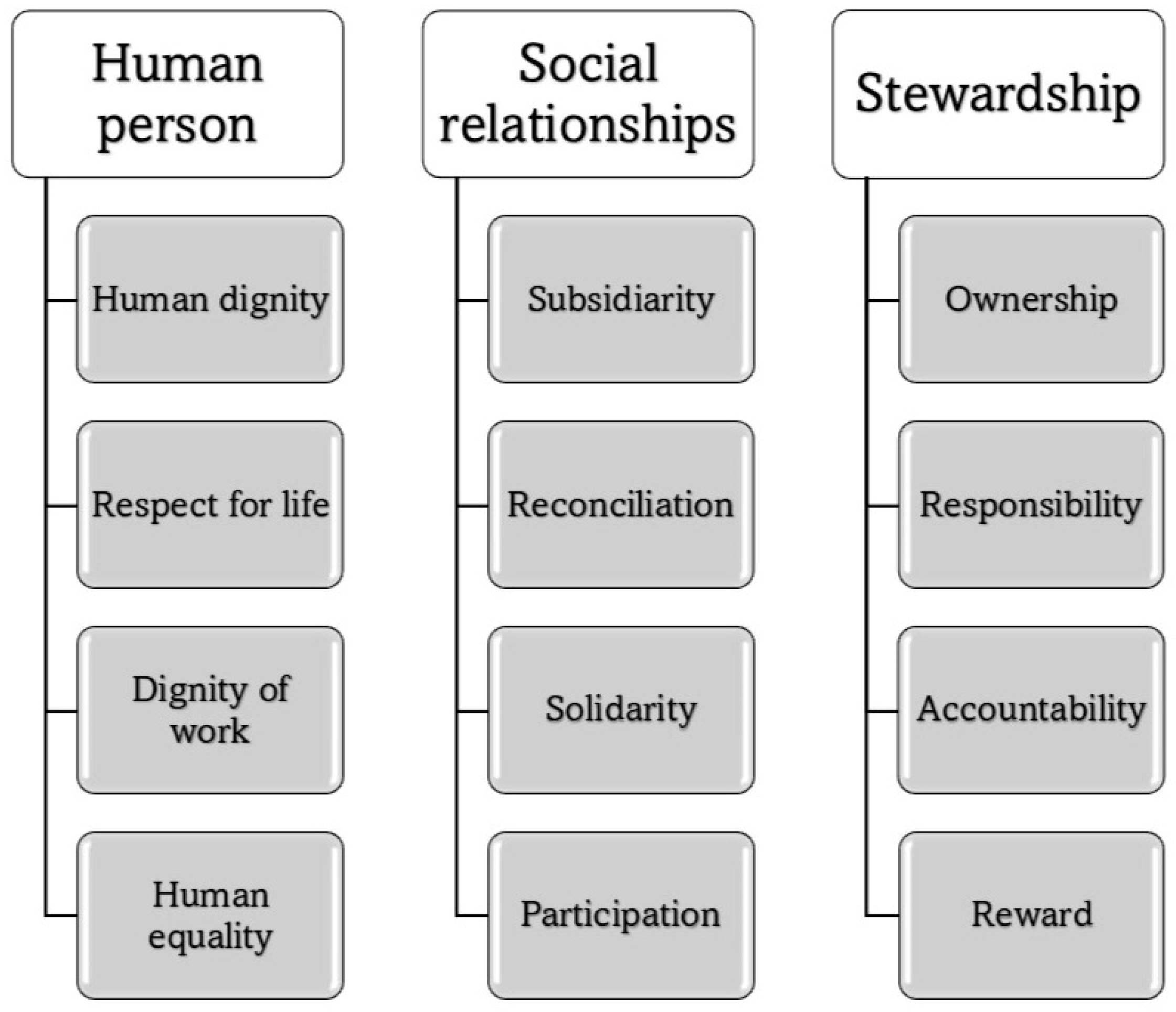

What does it mean to ‘align with the common good’ (

Figure 11), in the framework of an emancipatory educational relationship? In the 21st century, it is essential to establish links between what happens in society and what is taught in the classroom. In other words, we are committed to a humanist vision of education in which the social context is always considered (

Bounds, 1994).

Education is never neutral: it is conditioned by social, cultural, economic and political circumstances. Education is always based on a particular worldview of social life, responds to interests and pursues objectives. Based on this consideration, there are pedagogies that seek to promote conformist subjects and tend to the reproduction and permanence of existing structures (

Corbett & Guilherme, 2021). These are conservative pedagogies, abstracted from the surrounding realities, which tend to emphasise the introjection of predominant values, seek to maintain the status quo and, in essence, seek to limit themselves to training ‘good workers.

In the face of these, critical pedagogies (with which this proposal is aligned) emerge, interested in developing subjectivities committed to social transformation, justice and equality. Critical pedagogies aim to develop pedagogical alternatives that consider the experiences and realities of learners, stimulate their critical spirit and promote the development of attitudes and skills that enable them to commit and act in favour of their own emancipation and social justice For

Giroux (

2022), fostering critical consciousness in language education means creating learning spaces where migrants can reflect on their experiences, question dominant narratives about migration, and develop the linguistic and critical skills necessary to advocate for themselves and their communities. In this way, language education becomes a tool for liberation, equipping learners not only with linguistic proficiency but also with the confidence and agency to shape their own futures.

The difference between Critical Pedagogy and Critical Consciousness can help clarify the concepts further. Critical Pedagogy is an educational approach developed from Paulo Freire’s ideas, aiming to transform education into a tool for social emancipation (

Nugraha et al., 2024). It critiques traditional teaching models that impose knowledge in a vertical and passive manner, advocating for an education based on reflection, questioning power, and the transformation of social reality through dialogue and action. It considers the student an active subject in their learning, capable of critically analyzing their context and acting to change it.

On the other hand, Critical Consciousness refers to the state of deep thought and understanding that enables an individual to question and critically analyze their social, political, and cultural reality. This consciousness develops through education, dialogue, and experience. According to Freire, critical consciousness is the highest level of “conscientization,” where individuals not only understand their context but also seek to transform it. It is an objective of critical pedagogy, as this pedagogical approach aims to form subjects with critical consciousness who can act to generate social change (

Figure 12) (

Jemal, 2017).

What is the role of the teacher in this process and how should he/she deal with it? To facilitate the emergence of critical consciousness, the role of the teacher is fundamental. Not only to point out those aspects that the learner should problematise (the moral options available) but also to encourage him or her to do so. In this process, the analysis of the ethical aspects is as important as the aesthetics of the educator, which must be the result of previous work on himself/herself, which has allowed him/her to internalise and understand his/her role as an educator.

Critical pedagogy conceives teachers as transformative intellectuals, as opposed to the conception of the teacher as a mere executor of the curriculum. Thus, teachers are seen as independent, reflective and critical professionals, aware of the political and social implications of their work (i.e., in turn, as teaching subjects). They are, in short, active agents committed to the construction of the curriculum in their classes, seeking to foster the capacity and critical awareness of the student-subject, always starting from the position of empowerment and emancipation of their students (

Brinegar et al., 2018).

How does this process begin? Where does it start? The fundamental gesture, from which a pedagogical link is established that can lead to a relationship scheme compatible with the idea of a critical pedagogy, always starts with recognition. The idea of recognition is complex and, in essence, requires the renunciation of the conception of the educational relationship understood as an asymmetrical relationship, dominated by the educator, understood as an agent transmitting a predetermined cultural selection (a curriculum), decontextualized, alien to the interests and concerns of the learner and which, above all, is not questioned.

On the contrary, the idea of recognition as an essential basis in any authentically educational relationship (and even more so in the context of language teaching to migrants), requires conceptualising the educational relationship as a meeting of two subjectivities (that of the teacher and that of the learner) in development (the process of subjectivation is never complete) which are committed, each in their own role, to the process. It is not possible to develop a pedagogical process aimed at generating critical conscience if, first, this encounter and recognition do not take place.

Who is the learner who summons us to this relationship? Where does he/she come from? Why does he/she come? What is his/her background? What is he/she like? What does he/she believe in? What does he/she want to do with his/her life? These questions, and others like them, are the ones that should preside over and underline the pedagogical relationship that is established between educator and learner. Asking these questions, moreover, should not be the result of a merely ‘informative’ interest (collecting data), aimed at ‘better adjusting the curricular proposal’ (a kind of initial diagnostic evaluation). On the contrary, what should motivate these, and other questions should be a genuine and authentic interest in knowing and understanding our interlocutor (

Skliar, 2017). This interest represents the essential gesture of welcome that forms the basis of what is known as the pedagogy of hospitality.

This hospitable relationship also involves asking oneself, the educator, who am I in this relationship? Who do I want to be? How do I want to be in this relationship? Why am I in it? What do I want? What do I believe about migrants? These and other reflections must also be made explicit within the framework of the relationship, generating a space of mutual recognition, of reciprocal understanding that allows the foundations of an emancipating pedagogical relationship to be established: a horizontal relationship, which is built on dialogue, seeking a genuine understanding of the other.

This ‘openness’ to the others, seeking their essential recognition, does not imply uncritical affirmation of the other (unconditional acceptance of their beliefs and positions), but can and should sometimes lead to a critical and problematising dialogue that forces the other to rethink issues or aspects that can and should be questioned. In other words, what we are talking about here is not an indulgent, easy pedagogy, oriented towards always overprotecting the learner. Rather, it is a committed pedagogy, which accepts the other in his or her actual being, but which is also committed to his or her transformation.

The role of the teacher/educator in this sense should be very similar to that of a cultural ambassador, of one’s own culture, the welcoming one, towards the immigrant subject, representative of another cultural reality. The educator, with the refinement and respect of an ambassador, must show his or her values and beliefs, without trying to impose them, but simply to problematise them, explain them and reinterpret them in the light of the viewpoint of the immigrant teacher, who comes from another cultural reality. In no case should this relationship be conceived as a process of cultural indoctrination or of inducing a process of replacing one’s own beliefs and values with those of the host culture (or those of the teacher/educator) (

Coda, 2012;

Gjurčinova, 2022).

How far have/have the above ideas developed in the field of language teaching? In the field of foreign language teaching and learning, critical pedagogy is a more recent phenomenon than in general education, although there is an increasing number of studies and educational practices that fall under the umbrella of critical pedagogies. Critical pedagogy invites language teachers to make explicit in the classroom the connections between language and its wider social context, thus exploring the socio-political implications of language education and knowledge production.

In applied linguistics and sociolinguistics, the term ‘critical’ refers to types of approaches that question prevailing arguments and perspectives: they take a sceptical view of assumptions and ideas that have become natural. One focus of critical research in language education in recent years has been to examine the influence of neoliberalism—the latest mutation of capitalism—on foreign language teaching and learning.

Various studies have indicated that neoliberalism has promoted a view of language as economic capital, prioritizing its instrumental value over its cultural and social dimension (

Block et al., 2012). In this sense, language policies in many countries have favoured the teaching of English as a resource for employability, while relegating minority languages to the background (

Heller, 2010). The impact of neoliberalism is also visible in the conception of learners as entrepreneurs and consumers, and of teachers as mere providers of language skills. Moreover, the neoliberal nature is very much present in language textbooks, which highlight individualism, entrepreneurship and consumerism in their content and activities, as studies of foreign language teaching materials demonstrate.

Which methodological or didactic approach seems the most appropriate, in view of the above? Any physical framework and any methodological format can be valid if it is done from a dialogical and non-horizontal position, based on recognition. However, the counter-hegemonic and transformative teaching conception of critical pedagogy imagines a dialogue of knowledge that allows for an interlinguistic pedagogy of reception or hosting (

Figure 13). A pedagogy without hosts that conceives the teacher as a guest, thus breaking with the traditional separation between theory and practice in the field of education.

It consists of understanding teaching as a process of shared discovery, an encounter between travellers in an inn, and a process of conversation between subjectivities, for the improvement of educational practice through the art of living together. It is a subjective and interventionist approach to the educational process (

Brew & Saunders, 2020).

A

didaxis of interculturality, i.e., the methodology stemming from a pedagogy of hospitality, is an interlinguistic method of hosting that requires teacher training in cultural competence, with a greater emphasis on the actual concept of cultural humility (

Lekas et al., 2020).

A very appropriate way of establishing relations between classroom teaching and what is happening in society is using real texts dealing with current issues; social literature, selected filmography, analysis of works of art, plays… In this way, students will be encouraged to reflect on the contents and share criteria collectively, to improve their critical capacity. This favours students’ awareness of the social transformations that need to be carried out in the world and encourages them to assume an active and critical role as active citizens of the 21st century. Consequently, emphasis is placed on the transformative power of education, and therefore, in addition to the importance given to didactic aspects, the role of education as a socialising tool is highlighted.

What contents, competencies or skills can be the referents for the design of activities that structure the pedagogical relationship? (

Figure 14) To get to know different social realities, it is necessary to base teaching on social competencies among which communication, cooperation, leadership, influence and conflict resolution stand out.

At all times, students should be invited to delve into the socio-political and cultural context in which the educational process takes place to foster a relationship between what is taught in the classroom—or in other pedagogical meeting places—and what is happening in society. This goes hand in hand with education for global citizenship, which implies openness to social realities other than one’s own and awareness of individual responsibility in different social aspects, including social justice.

An educational approach based on a pedagogy of hospitality or interlinguistic hosting helps us to become aware of the social inequalities that exist today, to make it visible that many people are deprived of rights and of being active citizens in this globalised world, to pay attention to people who are currently oppressed and to all forms of social injustice. Thus, there is an opportunity to design activities that enable pupils to advance as global citizens and, at the same time, to deepen the importance of interculturality.

When teaching language classes, when teaching a new language, we consider it essential to work with these resources that allow us to introduce social issues that help migrants and professionals who work with them, to deepen their knowledge of different realities and different socio-cultural issues, as well as to share their own life experiences, their journey, their uprooting, their expectations, their cultural heritage. This will give us the opportunity to work with key concepts for coexistence, such as power, ideology and discourse. These types of activities and resources will allow us to go deeper into the context to which they refer and to establish relationships between the discourse used and the social reality in which it is framed.

What kind of resources should be used? Is it important to choose textbooks specifically oriented towards a canonical knowledge of the language or should communicative competence, based on the issues underlying the educational relationship, take precedence? The resources used and recommended should not only improve the level of acquisition of a new language by migrants, encouraging the study of specific vocabulary related to intercultural aspects but also favour the acquisition of social competencies such as cooperation between people or communication; empathy and respect for diversity are also enhanced. Multimodal texts help to observe how meanings are expressed through different modes of communication. In this way, forms of literacy different from traditional grammaticalisation (morphology and syntax without semantics) are promoted, including in teaching the use of images and other modes of communication and transmission of educational content close to the learner’s reality and provoking new centres of interest and motivation. Consequently, it is stressed that language evolves due to social changes, i.e., language is a system of meanings that allows people to select between different options, considering the objectives of communication, always influenced by the social context.

We believe that it is essential to base teaching on social content so that pupils can broaden their vision of social realities other than their own and can work on skills related to respect for diversity.

Every multimodal text, every artistic-cultural creation, fulfils a symbolic function closely linked to the process of shaping cultural memory, insofar as it not only creates information but is able to store, save and accumulate it in its structure throughout its uninterrupted dialogue with culture; thus, meaningful texts and other resources become cultural symbols and the foundational memory of a shared culture.

Establishing relationships between text and context (by text we mean any chosen learning tools, readings, writings and/or shared viewing), helps learners to consider active social engagement that contributes to transforming unjust social realities.

Power relations present in the chosen resources or activities, such as the exploitation of Southern countries by Northern countries or power relations between women and men, must be deconstructed. This is related to promoting cross-cutting themes in the classroom such as those related to cultural aspects or gender issues (the reality of the countries of the North and the South, armed conflicts, the struggle for territories, forced displacements, the situation of refugees, the unfair distribution of wealth, the ecological crisis, discrimination based on race, religion or gender… themes related to development cooperation or human rights) as these themes contribute to raising students’ awareness of shared realities, common histories in diverse geographies. And, where necessary, it facilitates the questioning of morally unacceptable beliefs, practices or cultures, from a basic human rights perspective.