1. Introduction and Background

Thus far, the 21st century has witnessed rapid technological development (

Spring, 2012). Practitioners and educators are now frequently reminded of the incompatibility of traditional teaching methods with modern students, as they contradict both the new generations’ expectations of school and the requirements of the contemporary workforce, which is heavily influenced by technological advancements.

In English education, beyond the conventional basics of reading and writing, future generations must be equipped with ‘multiliteracies’ to understand and express meaning with various modes alongside linguistics (

Cope & Kalantzis, 2009;

Mills & Exley, 2014;

Rowsell et al., 2015) as well as ‘new literacies’, which emerge from the ubiquity of new technologies (

Lankshear & Knobel, 2011;

Nichols & Johnston, 2020) in order to address future challenges in communication, education and work. Moreover, technology integration has become a significant trend in English language teaching (ELT) (

Beach et al., 2010;

Wissman & Costello, 2014). Many have urgently called for more extensive teacher education and professional development programmes in digital literacy (

Hobbs & Coiro, 2019). Seeing the need to foster students to be literate in a 21st-century sense (

Jenkins, 2007;

Trilling & Fadel, 2009), many ESL teachers have reconsidered their initially negative views on technology integration (

Nazari et al., 2019;

Rauf & Suwanto, 2020) and have begun to incorporate technology into their practices. Consequently, many technological innovations in teaching have been noted. For example, ESL teachers have been inspired to use various digital tools to teach oral skills (

Zhang & Deng, 2015) and writing skills (

Bai et al., 2021;

Park & Wang, 2019), and they were empowered to conduct online teaching (

Moorhouse & Kohnke, 2020) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, they have explored the affordances of the Metaverse platform to provide learning opportunities for students (

Kurniawan et al., 2023), and they have leveraged English learning websites and chatbot text-chatting services to bolster students’ development in vocabulary, sentence structure and interpersonal communication (

Tseng, 2018).

However, in daily practice, ESL teachers routinely avoid using technology in their teaching. In fact, in some educational settings, extrinsic contextual factors (

Ertmer, 1999), such as limited access to technology and technical difficulties (

Abbasi et al., 2021;

Tosuntaş et al., 2019), discourage teachers from incorporating technology into their standard practices. Still, even in teaching contexts with higher levels of technology access and technical support, ELT frequently exhibits a low level of technology integration (

Dwiono et al., 2018;

Jude et al., 2014;

Shi & Jiang, 2022;

Tseng, 2018;

Webster & Son, 2015).

It is evident that a positivist mindset when it comes to overcoming extrinsic contextual challenges may not be sufficient to effectively ameliorate the current situation. This is because technology integration in education is a social endeavour that requires human participation and openness of teachers to adopt a new mindset (

Lankshear & Knobel, 2006).

Tosuntaş et al. (

2019) pointed out that when external barriers are eliminated, there are still other decisive teacher-related factors that influence successful technology integration. These factors are usually typically not readily understood in the natural sciences (

Robson & McCartan, 2016).

Earlier research has highlighted that ‘teachers are active, thinking decision-makers, who play a central role in shaping classroom events’ (

Borg, 2006, p. 1): they are the key factor behind technology integration in teaching (

Chen, 2008) because what they ‘think, know and believe’ (

Borg, 2006, p. 1) essentially mediates the integration. Recent research has ascertained that ESL teachers’ resistance to change stems from negative attitudes towards and beliefs in technology (

Shi & Jiang, 2022;

Singh et al., 2018;

Tosuntaş et al., 2019) and their lack of digital competence and pedagogical knowledge regarding the use of technology in lesson design (

Merç, 2015;

Tosuntaş et al., 2019;

Yunus et al., 2013). Just as

Borg (

2013) argued that language teachers’ attitudes, beliefs and knowledge are interconnected and interdependent, policymakers believe that equipping ESL teachers with suitable technology integration knowledge and skills can inspire them to use technology in a way that improves their teaching and will make them more ready and confident to bring technology into their practices.

With an emphasis on addressing teachers’ needs for technology-integration-related knowledge and skills, the Hong Kong government invested over 10 billion HKD to implement four 5-year IT in education (ITE) strategies in order to promote e-learning (

EDB, 2015). The aims of this initiative are to provide teachers with training and install up-to-date infrastructure across the territory’s schools. Nonetheless, while schools’ infrastructure has been upgraded, the standalone and technological-knowledge-focussed training workshops fell short when it came to equipping teachers with suitable knowledge and skills to use technology effectively in teaching. Local ESL teachers are still struggling and feeling anxious about adopting technologies in practice (

Chiu & Churchill, 2016).

For example,

Park and Son (

2020), using semi-structured interviews to study pre-service ESL teachers’ experiences using technology in their teaching practicum during their first year of full-time teaching, found that teachers who were digitally fluent still encountered difficulty bringing technology into their teaching due to limited pedagogical knowledge, time constraints, tight teaching schedules and school policy and culture.

Moorhouse’s (

2021) qualitative online survey-based study, which investigated novice English teachers’ technology-integration practices during the COVID-19 pandemic, indicated that a lack of pedagogical knowledge limited teachers’ ability and competence to achieve effective technology integration in teaching.

Bai and Lo (

2018), who surveyed 36 in-service primary school English teachers from different schools in Hong Kong, reported similar findings regarding barriers to technology integration in teaching.

These studies indicate that inexperienced ESL teachers are prone to being affected by external contextual factors. Moreover, the factor of pedagogical knowledge regarding the incorporation of technology into teaching significantly affects not only pre-service and novice ESL teachers but also experienced ESL teachers. This observation was further confirmed by

Shiu’s (

2024) recent study on online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic, which found that existing institutional and contextual factors could be addressed more readily with proper financial support. However, ESL teachers’ limited technological and pedagogical knowledge (TPK), which stemmed from their limited understanding of affordances of different technologies and their disability to repurpose digital tools for pedagogical use, prevented ESL teachers from successfully incorporating technology into their practices.

In a context with significant efforts to provide suitable infrastructure but unfocussed training, it is pivotal to provide ESL teachers with TPK so that they will be ‘skilled at choosing and using the right technologies in their lesson plans’ (

Leong & Yunus, 2024, p. 196). Despite the pressing need to equip ESL teachers with appropriate knowledge, there has been a dearth of research on the practical knowledge necessary for ELT. Tackling this key research gap, this paper, as part of a large study for the author’s unpublished doctoral thesis (

Shiu, 2020), examines the technology-integration practices of three ESL teachers who played a leading role in promoting IT in English education at their respective schools in Hong Kong to conceptualise a typology covering the features of different types of commonly used technological tools and their various pedagogical affordances. This typology aims to inform practitioners’ practices and serves as a reference point for teacher educators and workshop developers to design targeted and optimised training. Moreover, as new insights and contributions beyond those of the original, larger study, this paper synthesises an improved TPACK–ELT framework from the findings to provide deeper understanding of the relationships between the characteristics of digital tools and their pedagogical affordances when it comes to technology integration in ELT.

2. The TPACK Framework

As highlighted by

Mishra and Koehler (

2006), effectively using technology to teach a subject with suitable pedagogy requires teachers to acquire technological, pedagogical and content knowledge (TPACK), a form of knowledge stemming from and transcending the synergy of content, pedagogy and technology.

The conceptualisation of TPACK was based on

Shulman’s (

1986) notion of pedagogical and content knowledge (PCK). It comprises:

Content knowledge (CK)—‘knowledge about the actual subject matter that is intended to be learned or taught’ (

Angeli et al., 2016, p. 15).

Pedagogical knowledge (PK)—‘knowledge about the processes and practices or strategies about teaching and learning’ (

Angeli et al., 2016, p. 15).

Pedagogical and content knowledge (PCK)—‘knowledge of pedagogy that is applicable to the teaching of specific content’ (

Koehler & Mishra, 2008, p. 14).

Technological and content knowledge (TCK)—‘a deep understanding of the manner in which the subject matter (or the kinds of representations that can be constructed) can be changed by the application of technology’ (

Koehler & Mishra, 2008, p. 16).

Technological and pedagogical knowledge (TPK)—‘an understanding of how teaching and learning changes when particular technologies are used [and] a deeper understanding of the constraints and affordances of technologies and the disciplinary contexts within which they function’ (

Koehler & Mishra, 2008, p. 16).

TPACK is a kind of ‘contextualised and situated synthesis of teacher knowledge’ (

Angeli et al., 2016, p. 16) that provides for learner diversity when teaching specific content using technology. The framework has significantly bolstered educators’ understanding of effective technology integration and is now widely used to assess teacher knowledge and promote professional training in the subjects of maths and science (e.g.,

Baran et al., 2016;

Mouza, 2016;

Polly & Orrill, 2016). However, its application in ESL/EFL classrooms is still limited (

Bugueño, 2013;

Leong & Yunus, 2024;

Shi & Jiang, 2022).

Some earlier uses of the framework in ESL include

Hughes and Scharber’s (

2008) study comparing the difference in TPACK development between pre-service and experienced English teachers. It concluded that a lack of real teaching contexts to enable authentic pedagogical and technological considerations in teaching has hindered pre-service teachers’ TPACK development. Addressing the unfavourable situation,

Asik (

2016) and

Wang (

2016) separately conducted their mixed-method studies, which leveraged the creation of digital stories as an intervention for ELT, and found that such stories improved pre-service ESL teachers’ instructional design capabilities as well as their TPACK. Moreover,

Wu and Wang’s (

2015) mixed-method study on the TPACK of 22 Taiwanese in-service primary school ESL teachers found that the teachers’ TPACK development was hampered by a lack of TK. Additionally, their use of technology was strictly limited to motivational purposes, falling short of meaningful integration. In essence, earlier research has indicated that ESL teachers’ development of TPACK is reliant on situated practice to teach subject content with their TK and TPK.

Recent research has largely adopted self-reporting-based data collection strategies, such as questionnaires and interviews, to understand school and university English language teachers’ TPACK (e.g.,

Cahyono et al., 2016;

Leong & Yunus, 2024;

Nazari et al., 2019). The findings highlight the need to provide teachers with lists of useful technologies and their corresponding applications to enhance their decision-making pertaining to the choice of suitable tools for specific pedagogical purposes (

Cahyono et al., 2016). Moreover,

Shi and Jiang (

2022), by surveying and interviewing teachers, found that ‘TK was the key source’ (p. 7) affecting the conceptualisation of ‘TPK and TCK and ultimately, TPACK’ (p. 7) in their practices. They concluded that ‘technological training should be integrated with CK and/ or PK’ (p. 13) with ‘educative examples’ (p. 13) to exemplify how technologies can be pedagogically leveraged to teach different elements of subject content. With the same concern,

Nazari et al. (

2019) suggested that training focussed on the use of TPACK in classroom settings should be implemented by teacher preparation courses as well as in-house professional workshops. Evidently, the recent literature offers insight into means of improving technology integration, including through helping ESL teachers to obtain the skills necessary to operate technological tools and to understand the relationship between tools’ fundamental functions and educational affordances for pedagogical use within real classroom contexts.

The existing literature demonstrates that the TPACK framework is a promising research framework for providing a theoretical understanding of how ESL teachers’ technology integration practices are framed by their knowledge of technology, pedagogy and content across various teaching contexts. It also serves as a practical tool for analysing ESL teachers’ technology-integration practices alongside the interplay of the three forms of teacher knowledge (

Hamilton et al., 2016). Existing studies on TPACK in ELT have relied heavily on self-reporting data collection strategies in both quantitative and qualitative research. Therefore, there is a need to broaden the understanding of the topic by examining qualitative data ‘through collecting teachers’ lesson plans, observations, stimulated verbal and written reports, and reflective journals’ (

Nazari et al., 2019).

3. The SAMR Model

Aside from the TPACK framework, another framework that has garnered popularity in research on technology integration is the SAMR model developed by

Puentedura (

2006). This model, ‘as a ladder, is a four-level approach to selecting, using, and evaluating technology’ (

Hamilton et al., 2016, p. 434). These four levels are substitution, augmentation, modification and redefinition. The model serves as an analytical tool for evaluating levels of technology integration in learning tasks.

In an ELT context, the SAMR model facilitates an understanding of how technology can enhance or transform language learning activities. For example, when technology is used at the substitution level in an English language learning activity, it is replacing traditional tools without providing any functional improvement. One example of substitution is when students use the camera application on their cell phones to create videos for speaking assignments (

Gromik, 2012). In this case, the technological tool has substituted traditional means of completing assignments with a convenient means of practice.

At the augmentation level, technology is used to replace traditional tools in a way that offers functional improvement in a learning task.

Chen’s (

2013) study found that tablets, which offer various helpful functions for English learners and enable them to look up new words, learn pronunciation and have their grammar checked, enhanced informal language learning. In this case, the tool provided a functional improvement, augmenting the learning process outside of the classroom.

At the modification level, language tasks are redesigned by incorporating technology. One example of modification may be found in students in a speech and debate course being empowered with personalised learning opportunities by various mobile social media applications, including ‘Facebook, LINE (a social networking site from Japan), WeChat, Google Hangouts, and YouTube’ (

Wang et al., 2013). In this case, the tools not only offer flexible resources, time and space to learn outside of the classroom but also facilitate interconnectivity among learners.

At the redefinition level, technology facilitates the creation of new tasks that cannot be realised without technology.

Liu and Tsai (

2013) conducted an exploratory case study to examine the effects of a self-developed augmented-reality (AR) application on Chinese students who learned to write in English using the application on their cell phones, which leveraged GPS to get information in English about different things around them. In this case, the tool afforded them a personalised, situated and information-connected learning style (

Romrell et al., 2014). This kind of learning experience would be inconceivable without the support of technology.

It should be noted that while substitution and augmentation enhance language learning activities, modification and redefinition have the potential to transform learning (

Puentedura, 2006). The SAMR model assists researchers in understanding how technology empowers teachers to design or redesign learning tasks (e.g.,

Budiman et al., 2018;

Romrell et al., 2014). The model has been employed more often in higher education studies than at the school level. For example, in a multi-case study that employed a mixed-methods approach to collect self-reported data,

Muslimin et al. (

2023) used the SAMR model to examine six English lecturers’ levels of digital literacy competence (DLC) and technology integration. They found that the teachers perceived themselves as having a high level of DLC. However, their teaching practices pertaining to technology mainly reflected substitution and augmentation. Comparable results were reported using the SAMR model by

Cepeda-Moya and Argudo-Serrano (

2022), who evaluated technology integration among 31 university professors’ teaching practices and 34 university students’ learning practices. This low integration level was also widely observed in pre-service English teachers’ technology-integration practices (e.g.,

Boonmoh & Kulavichian, 2023;

Harmandaoğlu Baz et al., 2018;

Howlett et al., 2019). This dynamic has prompted a need to integrate the SAMR model into an ESL teacher preparation course and curriculum (

Harmandaoğlu Baz et al., 2018). Some have suggested that skilful and experienced mentors and coaches should be involved in professional training to provide specialist insights and specialised perspectives on how to use technology at higher levels in language learning activities to facilitate pedagogical improvement (

Howlett et al., 2019). The low level of technology integration was also found in the few recent studies that have been conducted at the school level (e.g.,

Cheung, 2023;

Özkan & Aşık, 2023).

Meaningfully integrating technology to promote pedagogical improvement in ELT requires teachers to acquire the knowledge and skills necessary to coherently blend content, pedagogy and technology. Moreover, considering their specific teaching and learning contexts, teachers may use technology to achieve different pedagogical purposes. The TPACK framework offers an insightful understanding of the interplay of technology, pedagogy and content knowledge in ELT, and the SAMR model offers useful perspectives on how technology enhances and transforms language learning tasks in ELT. Therefore, this paper employs the TPACK framework and the SAMR model as analytical frameworks through which to interpret the teaching practices of ESL teachers in Hong Kong schools.

5. Findings

5.1. Comparison of the Three Teachers’ Technology Use in Their Practices

This paper’s findings show that all three of the considered teachers used technology at both lower and higher levels. The lower levels of technology use for substitution and augmentation included using technologies for classroom management, organising teaching activities, motivating students, supporting students’ emotional needs, providing authentic teaching materials and promoting the efficiency and effectiveness of teaching. The use of higher levels of technology was mainly for the purposes of modification, which entailed using technologies to scaffold learning in more effective ways, conduct research, tailor teaching materials to learner diverse, foster students’ research skills and collaboratively create multimodal texts and learning products.

Examining the common technological tools used by the three teachers (e.g., Kahoot!, PowerPoint, YouTube, Google Search, engine and websites) revealed that their practices exhibited similar patterns of substitution, augmentation and modification in pedagogical needs (see

Supplementary File S8).

However, evaluating the different technological tools used by the three teachers revealed different patterns in the teachers’ teaching practices. Wendy used the highest number of distinct tools. The analysis showed that her integration of these tools supported the use of augmentation and modification (with an emphasis on the former). Moreover, Wendy used these tools to teach both conventional and contemporary literacies. For example, she used Quizlet, Nearpod, GoodNotes and Random Name Picker to assist her in conventional literacy instruction. Moreover, enhancing students’ consumption of contemporary literacy, she adapted the affordances of Nearpod and Edpuzzle to introduce students to this kind of literacy and teach them how to interpret and use it. Finally, the analysis indicated that Wendy’s technology-integration practices mainly emphasised the enhancement of individual students’ learning. From the observational data, there was only one occasion on which she adapted YouTube to support collaboration and communication in a jigsaw listening activity (see

Supplementary File S8).

As for Jack’s case, he used the lowest number of distinct tools in his teaching but exhibited the highest number of occasions on which he used those tools for modification to enhance students’ learning of contemporary literacies and develop the 21st-century skills of digital literacy, communication, critical thinking, collaboration and creativity. For example, Jack used Adobe Spark to create websites tailored to students’ abilities for their research. He relinquished control of technology to students so that they could create their multimodal texts collaboratively using Google Slides for presentations and discussions. This indicated that Jack’s practice in contemporary literacy instruction was focussed on students’ consumption of contemporary literacy as well as their creation of contemporary literacy. Moreover, supported by technology, his project-oriented teaching emphasised students’ collective intelligence rather than their individual intelligence (see

Supplementary File S8).

Liz’s practice of technology integration resembled those of Wendy and Jack. She used a higher number of distinct tools than Jack and adapted them for both augmentation and modification (with a focus on the former) to support classroom management and bolster the effectiveness of her teaching. The tools that Liz chose to use in her teaching consisted mainly of digital platforms, namely Padlet, Google Classroom, Quizizz and Mentimeter, enabling her to manage teaching logistics, create learning activities, track students’ progress and provide them with instant feedback. Supported by technology, she sought to teach conventional literacy (as per the curriculum) while infusing contemporary literacy into it alongside formal classroom instruction. For example, apart from allowing students to consume contemporary literacy by searching for useful online materials (e.g., websites, YouTube videos and websites), Liz appealed to students’ critical thinking, encouraging them to delve into the underlying messages of online videos and digital texts. She also prompted students to engage in online discussion and collaborative writing for the drama production. In her teaching, she focussed on students’ individual intelligence as well as their collective intelligence (see

Supplementary File S8).

The following subsections provide a succinct description of each participant’s teaching of a unit of work as well as three teaching episodes showing their higher-level technology use, presented and explained through the within-case analysis. Next, this paper interprets the findings of the cross-case analysis and offers a conclusion.

5.2. Wendy’s Teaching Practice

Wendy taught a module titled ‘Environmental Conservation’, covering nine lessons in her Secondary Three class. It introduced the four language skills (i.e., reading, writing, listening and speaking) and grammar. She employed textbooks and a school-based booklet for instruction. In the unit, students read a leaflet about global warming and wrote a speech with the following message: ‘Save the earth’. The grammar item, the third conditional sentence, was also introduced. (For a more detailed overview of the unit’s content, see

Supplementary File S4.)

Before teaching the unit, Wendy used Quizlet to create flashcards and a matching exercise for students to self-learn the target vocabulary related to the concept of environmental conservation. Wendy used a song on YouTube to gauge students’ prior knowledge about reducing, reusing and recycling (the 3Rs) to begin the unit. She then engaged the students in a discussion about which ‘R’ was the easiest to promote in Hong Kong. Wendy also employed a YouTube video about the 3Rs to design a jigsaw listening activity. The mobility and autonomy offered by iPads enabled students to watch and listen to particular parts of the video and then exchange information within groups.

Moreover, Wendy used the Nearpod digital platform to design mini-learning tasks for guiding the students when reading the leaflet about global warming and encouraging their participation in voting and answering comprehension questions. Embedding a hyperlink to a website about carbon footprints on the platform, Wendy taught her students to use the website in order to calculate their carbon footprints. As for teaching the grammar item of the third conditional sentence, Wendy used PowerPoint to craft a presentation and a Kahoot! multiple-choice game for consolidation.

Finally, Wendy encouraged her students to use technology to research the problem of pollution as well as potential solutions for it and to organise their writing ideas for a ‘Save the Earth’ speech using a digital mind-map on Popplet.

5.2.1. The First Episode: A Jigsaw Activity for Promoting Listening Comprehension

Wendy leveraged the mobility of iPads (TK) to design a jigsaw listening and speaking activity to boost her students’ listening skills (TPACK), which had been identified as part of their language needs. She selected a YouTube video titled ‘Reduce, Reuse and Recycle to Enjoy a Better Life’ (TCK) as the listening material. The contemporary digital text promoted learning through authentic discourse and fostered development of the ‘speed of delivery, accent, and formality of language’ (

Hedge, 2000, p. 246).

Wendy used iPads to enable students to work in different groups (TK). She first divided the class into four large groups. Each group listened to one of four parts of the video and completed a portion of the video script by filling in the blanks on a worksheet. In this case, iPads afforded the students the autonomy to listen for specific information at their own pace in each group, thereby revamping the traditional teaching practice of whole-class listening (

Ahmed & Nasser, 2015;

van Olphen, 2008). After completing this task, the students were regrouped into small groups of four. Without being able to show their worksheets to one another, the students in each new group exchanged information by asking and answering questions to complete the video’s entire script.

Classroom listening instruction tend to be one-way and teacher-centred, with the teacher holding authority to control the entire process by offering instructions, playing recordings, checking answers and providing feedback. Individual students are expected to respond accordingly to various listening tasks in a passive manner within given time limits. Students often feel helpless when they cannot keep up with the speed of the recording or become stuck on some difficult question, and they are often demotivated by the tedious learning tasks and the monotonous learning pattern. Using technology, Wendy successfully modified and redesigned the traditional listening activity in a way that enhanced students’ participation at their own pace and encouraged collaboration to complete the task (

Puentedura, 2006).

5.2.2. The Second Episode: A Nearpod Reading Activity

Wendy made use of the Nearpod digital platform (TK) to design three miniature reading tasks (TPK) in order to guide students through a leaflet on ‘carbon footprints’ (TPACK). Working on their iPads, the students first answered an open-ended question ‘What is a carbon footprint?’ to retrieve their prior knowledge before reading. Next, to guide students towards reading and checking their comprehension, Wendy asked them to conduct a poll on the digital platform for suitable means of consuming different resources while reading. In the first two mini-tasks, Wendy used the digital platform to encourage the entire class’s participation, assess her students’ reading comprehension and provide instant feedback (TPK).

In the final mini-task, Wendy asked the students to click an embedded hyperlink on the ‘parkcitygreen.org’ website. Students were asked to read the web page’s instructions to calculate their carbon footprints (TCK). Afterwards, Wendy took one of the students’ digital reports of carbon footprint reports as an example and explained how to interpret the details. The experience of navigating a website for information and reading the digital report to understand its implications (TCK) gave students a better understanding of the concept of carbon footprints (TPACK), exposed them to authentic and contemporary literacies (TCK) and connected their learning in school to real life.

Overall, technology enabled Wendy to enhance a conventional and monotonous reading activity, which required students to read a text and answer related comprehension questions individually in a textbook. The augmented activity provided an interactive textual reading environment with various mini-tasks and instant feedback to engage students’ learning experience (

Puentedura, 2006). In addition to fostering a purposeful reading process (

Hedge, 2000), it also engaged students with meaningful use of contemporary literacies to motivate learning (

Lankshear & Knobel, 2006).

5.2.3. The Third Episode: A Digital Mind-Map Construction and Research Activity

Wendy employed a digital mind-map, Popplet (TK), on iPads to help students generate and organise their ideas before writing a speech on ‘environment conservation’ (TPACK). This tool allowed students to use various multimodal modes (

Cope & Kalantzis, 2009) such as typing words, downloading images, drawing and taking photos to represent their ideas (TK). Wendy emphasised that constructing a mind-map enabled students to brainstorm more ideas by reflecting on their prior knowledge (

Hedge, 2000) and to express themselves in different ways.

Moreover, the affordances of iPads with WiFi encouraged students to research relevant information online and self-learn new vocabulary related to the writing topic through the use of Google Translate (TPACK).

In this episode, Wendy integrated technology to augment a conventional writing task (

Puentedura, 2006) and empowered her students with technology (TPK) to facilitate their active construction of knowledge. Her decision to delegate control of technology to the students also encouraged active learning and self-directed learning. Overall, her technology-integration practice focussed on improving traditional and conventional teaching practices by leveraging technology to augment and redesign existing learning activities in a manner that yielded pedagogical improvements (

Puentedura, 2006).

5.3. Liz’s Teaching Practice

Liz’s work unit was a module titled ‘Wonderful Asia and Travelling to Asia’, which covered 11 lessons in her Secondary Two class. It consisted of three texts for reading: a poem titled ‘Across Asia’, a travel guide titled ‘Discover Asia’ and an email about a travel experience. Her students were tasked with creating a travel plan and writing an email inviting a friend to join them on a trip to Asia. To facilitate the learning of grammar, the unit made use of the future tenses. Liz also conducted drama rehearsals in two English language arts lessons during the observation period. (For a more detailed overview of the unit’s content, see

Supplementary File S5.)

To prepare her students for the module, Liz assigned them a pre-unit project in which students researched a country that they would prefer for a study tour and designed a physical pamphlet about a seven-day overseas study tour in that country. Through this project, the students became familiarised with vocabulary, content and text types relevant to traveling.

In her teaching, Liz incorporated various digital tools, namely Mentimeter, Quizizz and Kahoot!, to motivate her students, gauge their prior knowledge and introduce them to different travel attractions. She then covered the three reading texts and engaged her students in several textbook comprehension tasks. For the writing lessons, Liz employed two YouTube videos about travelling in Hong Kong and prompted her students to think critically about the videos’ delivered information and potential hidden messages, teaching them how to critically interpret information from online resources prior to selecting useful information for the writing component. Students then posted their writing plans on Padlet to receive peer feedback before drafting their invitation emails (the core writing task). Liz used PowerPoint to facilitate direct instruction and Kahoot! to teach the grammar element through consolidation. During the language arts lessons, Liz adopted a flipped-classroom approach that leveraged her students’ technological knowledge and skills to co-construct most of the preparation work for a drama production in an online environment; this included creating sound effects with an iPad to enhance a drama rehearsal.

5.3.1. The First Episode: Kahoot! For Grammar Learning Informed by Noticing and Hypothesising

In the grammar lesson, Liz provided no explicit instruction on grammar rules. Instead, she encouraged students’ ability to notice and hypothesise the underlying grammar rules (

Hedge, 2000) surrounding the use of five conjunctions ‘though’, ‘even though’, ‘although’, ‘despite’ and ‘in spite of’ using a game-like multiple-choice quiz designed on Kahoot! (TK and TPK). The digital game was followed by a constructive discussion on the use of conjunctions before Liz presented the grammar rules (TPACK).

Liz expressed that the ‘self-realisation’ of grammar rules is important because it enables students to internalise both the functions and forms of the target language. She indicated that the use of technology aided her in promoting the co-construction of knowledge (

Kim, 2001). Although the design of the digital multiple-choice questions resembled that of traditional questions, they were augmented by the Kahoot! Quiz’s instant feedback and timed questions (

Puentedura, 2006). Moreover, the use of technology enabled peer interaction, modifying the original teacher-centred instruction and elevating students’ passive learning into active inquiry (

Puentedura, 2006) and collaborative knowledge construction (

Vygotsky et al., 1978).

5.3.2. The Second Episode: Enhancing the Process of a Drama Production Through Technology

Liz leveraged Google, Google Docs and Google Classroom (TK) to enhance the scriptwriting and backdrop designs for a drama production through online collaboration and co-construction among students (TPK) engaged in the production (TPACK). Due to the limited lesson time in which to prepare the drama production during class, Liz flipped the classroom, requiring students to complete some of the preparation tasks outside the classroom. For example, she used Google Docs to enable students to collaboratively compose a script. She asked students to use Google Images to search for the production’s backdrops a day before class. The students then voted on the best images for the scenes and painted the corresponding backdrops in class. In this case, Google Classroom provided the students’ online workstations, housing their collaborative preparatory work. Thus, during the lesson observation when most of the logistics were ready, students in different groups for various aspects of drama production preparation work could make good use of the limited lesson time to finish painting all the backdrops efficiently for the rehearsal held during the next drama lesson.

Liz used technology to significantly redesign the traditional scriptwriting task (

Puentedura, 2006), enabling her students to collaborate in real-time using Google Docs to provide instant comments on the script and engage in online dialogues to discuss writing ideas. Additionally, they could access online resources for quick material searches when designing the backdrops. Consequently, students’ participation and collaboration were enhanced by their ability to work both asynchronously—as they contributed ideas at different times and from different locations.

5.3.3. The Third Episode: The Preparation of the Writing Process

The writing topic for the unit was composing an email to invite a friend on a trip to Asia. Liz adopted the process-based writing approach (

Harmer, 2001) to scaffold the learning. Understanding that her students’ writing abilities were relatively low and recognising that they were usually short of writing ideas, Liz put more focus on the pre-writing stage and carefully guided her students to make a travel plan by conducting online search for useful travel-related information and soliciting peer feedback on preliminary writing ideas before writing the first draft of the email.

During the pre-writing stage, Liz first shared her personal travel experiences with her students and invited them to share theirs. She then engaged the students to examine the content of two YouTube videos, titled ‘HK Vacation Travel Guide’ and ‘Top 15 Things to Do in HK’ and asked them to analyse how westerners and locals see Hong Kong differently. Finally, she led students in a discussion of the hidden commercial purposes of the videos produced by YouTubers. The purpose of the activity was to equip students with critical literacy skills for consuming online resources when they later conducted their research on the writing topic (TCK).

Liz then demonstrated how to search travel information about accommodation and flight fares on the website Skyscanner (TCK), after which she relinquished the technology to her students to conduct their online research (TPK) on various travel websites (TCK). They were tasked with learning useful, authentic details about travel destinations, accommodations and plane air tickets for their planned Asian trips (TPCK). In this way, Liz used the open and fluid digital media space to provide authentic, contemporary reading materials for writing. Students’ technological skills and knowledge of new literacies were extended as they conducted online research with critical thinking.

Afterwards, Liz asked students to synthesise the collected information to outline their individual travel plans using bullet points and post them on Padlet. Padlet was used not only for public sharing of writing ideas (TPK) but also as a platform for peer feedback (TPK). Students were given time to read others’ travel plans and provide comments to improve their classmates’ writing ideas before starting to draft their emails individually. To conclude, Liz leveraged the affordance of a combination of technology and authentic online resources to enhance students’ writing process (TPCK). It was observed that Liz’s writing lesson emphasised collective intelligence and that the students, being well prepared, were able to complete their first draft of the email by the end of the lesson.

Liz used technology to redesign the traditional writing task (

Puentedura, 2006) by challenging students to synthesise information from various online sources to create a new text. Students were granted significant autonomy to determine the content of their writing by consuming an array of contemporary digital texts and exercising their critical thinking to interpret and evaluate the information before using it. Moreover, Liz used Padlet for class-wide outline sharing and peer learning. Students were encouraged to provide feedback on classmates’ writing ideas, fostering a more participatory pre-writing process compared to traditional methods. Overall, Liz’s technology-integration practice focussed on improving traditional teaching and incorporating contemporary literacies using technology to augment and modify existing learning activities in a manner that yielded pedagogical improvements (

Puentedura, 2006).

5.4. Jack’s Teaching Practice

Jack’s lessons were part of his school’s Primary Five English curriculum, which centred on the teaching of English language arts and speaking skills. His lessons were designed using a project-based approach with a focus on integrated language skills. The observed project was titled ‘Inventions’ and covered four lessons. First, students read a reader titled ‘The Inventions of Thomas Edison’, giving them a concise historical understanding of some of Edison’s inventions. They were then tasked with conducting online research using one of four contemporary inventions: Google, mobile phones, Pokémon Go or Facebook. Students had to collaboratively create a PowerPoint in which they presented the findings of their research. (For a more detailed overview of the project’s content, see

Supplementary File S6.)

To introduce the project’s topic and pique the students’ interest, Jack showed them digital images of Steve Jobs and modern-day inventions. He then showed YouTube videos on Thomas Edison to help his students visualise the historic inventions, and he further helped them to understand the principles of those inventions using simple explanations in a group jigsaw reading task. Later, Jack used Kahoot! to create a digital game that assessed students’ understanding of the reader’s content. The game also promoted collaboration with a group work task and encouraged competition with other groups to answer questions about the reader. Afterwards, Jack shifted the focus from early inventions to contemporary ones. Again, he divided the students into groups to research contemporary inventions on tailor-made websites. Each group then created a presentation using Google Slides to present their research on one of four contemporary inventions.

5.4.1. The First Episode: Enhancing Reading Between and Beyond the Lines

When Jack reflected on the strategy he used to teach the same reader from the same project the previous year, he concluded that his prior teaching approach had been teacher-centred, emphasising class reading led by him as well as paired and silent reading by students to complete comprehension exercises. From his students’ performance in those lessons, he concluded that the traditional way of teaching readers and assessing student understanding was monotonous, demotivating and ineffective. Therefore, in this study when he once again taught the same project with the reader, Jack designed a jigsaw reading activity for students in groups to watch different short video clips about Edison inventions before reading the text about one invention. Next, the students were regrouped to exchange information about different Edison inventions. After the lesson, they were to finish the whole reader within a week, reading on their own time at home.

To assess students’ understanding of the reader’s content after home reading, Jack designed a competitive group game supported by Kahoot!’s multiple-choice function (TK and TPK). In groups of four, the students were prompted by the digital game-based (TPK) activity to collaboratively skim and scan the text for clues to answer multiple-choice questions (TPCK). The observation indicated that the students were greatly motivated in the competitive game. The constructive noises in the classroom indicated that they were highly engaged and deeply absorbed in the activity. Each group worked collaboratively to discuss the questions and look for correct answers from the reader. From the observations of the students’ performance in the game, most groups could answer the questions correctly. Jack discussed the more challenging questions with the whole class and prompted them to arrive at the correct answers with explanations.

To extend students’ learning from the factual information of Edison’s old inventions to appreciate the scientist’s insightful quotation about the value of hard work in achieving success, Jack showed a short video clip about Edition’s life story (TCK) embedded on Kahoot! (TPK) and challenged his students’ critical thinking to explain the underlying meaning of Edison’s famous quote: ‘Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration’. From the observation of the whole-class open-floor discussion, students demonstrated their eagerness to express their ideas and opinions. It was found that Jack possessed sound TPK and was able to leverage various affordances of Kahoot! to promote collaboration and critical thinking (TPCK).

By redesigning a traditional reading comprehension activity—one which focussed on print texts and individual intelligence—in a way that involved technology (

Puentedura, 2006), Jack extended the original curriculum of learning English subject content to incorporate contemporary literacy, which is digital and multimodal in nature (

Lankshear & Knobel, 2006). He enlivened the reading activity by leveraging the affordance of Kahoot! to provide gamified elements and engaged students with collaborative literacy, which prompted them to co-construct meaning through peer discussion and peer feedback (

Jenkins, 2009).

5.4.2. The Second Episode: Preparation for an Online Research Activity

Jack was determined to give his students opportunities to gain experience in conducting online research by visiting websites to read for useful information. Anticipating the difficult language used on authentic websites, which might overwhelm primary students, as well as the possibility that students might encounter inappropriate information online, Jack used Adobe Spark to construct four websites about four contemporary inventions, the Pokémon Go online game, mobile phones, Facebook and Google (TCK), for students to research (TPK). Age-appropriate language was used in those websites to suit his students’ language proficiency. During the project’s preparation stage, each group researched one of the four contemporary inventions by reading and extracting useful information from the tailor-made websites (TPCK). The research activity was scaffolded by a worksheet containing core questions that prompted students to search for information about each invention.

In the activity, Jack leveraged technology to produce suitable learning materials for students to conduct online research instead of engaging in a traditional library book search. With the fluid nature of online texts and multimodal features such as videos and audio resources found on websites (

Cope & Kalantzis, 2009), the activity was further modified to encourage students’ non-linear thinking and self-directed learning while enhancing their learning of contemporary literacies, digital literacy (

Lotherington & Jenson, 2011) and critical thinking as they researched information relevant to their research presentations (

Puentedura, 2006).

5.4.3. The Third Episode: Students’ Knowledge of Technology, Creativity and Critical Thinking

After collecting enough information about the four targeted contemporary inventions to answer the core questions, students collaboratively created a PowerPoint for their research presentations (TPK), having learned the skilled to do so from Jack’s demonstration of Google Slides (TK). During the lesson observation, it was found that technology supported Jack’s students in their delivery of creative presentation and inspired them to think critically about their use of certain inventions (TPCK). For example, one group designed a sketch to demonstrate how to conduct a book report on Pokémon; their goal was to present its online game. They also used various digital images to create the backdrop of their sketch during their presentation. Another group, during their question-and-answer session, discussed how to protect underage children from creating Facebook accounts by falsely claiming to be over 12, exhibiting critical thinking regarding technology consumption. These presentations reflected students’ collaborative (

Kalantzis & Cope, 2015) and collective intelligence (

Lankshear & Knobel, 2006).

Overall, the learning activity significantly restructured the traditional learning mode in which students are posed as passive learners (

Puentedura, 2006). The redesigned activity bolstered learning by doing as well as student collaboration (

Puentedura, 2006). Students worked together in teams to construct and co-edit a Google Slide with feedback provided by Jack. The final open-floor class question and answer session after each research presentation inspired students’ creativity, critical thinking and inquiry skills.

5.5. A Typology of Technologies Used in ESL Classrooms

Based on the identified fundamental affordances, the technological tools used by the teachers were analysed, and a typology of five types of technologies commonly used in local ESL classrooms was created. (For a summary of the analysis of the five types, see

Supplementary File S7.)

The first type are tech-based texts, which provide either texts of various written genres or multimodal texts. In addition to their function as teaching resources (e.g., YouTube videos, websites, blogs, digital images), tech-based texts also serve as teachers’ tools for presentation (e.g., PowerPoint, GoodNotes) and the creation of learning materials (e.g., Adobe Spark). Moreover, they are students’ collaborative presentation tools (e.g., Google Slides) and visual thinking tools for organising ideas (e.g., Popplet). In all three cases, technology provided educational resources for presentation in teaching. It enabled Jack to create learning materials tailored to his students’ language abilities. Moreover, the tools enhanced the learning process for students in Wendy’s case, who created a digital mind-map to organise writing ideas. Technology also enabled collective intelligence (

Lankshear & Knobel, 2006), as exhibited by the students in Jack’s case, who created a collaborative PowerPoint presentation.

The second type are tech-based functions via apps or online websites, most of which allow one function, but these may not inherently provide educational affordances. They enable teachers to collect students’ ideas for sharing (e.g., Padlet, interactive digital map) as well as their learning products in the forms of images or videos (e.g., the camera app). They also provide technical support through shortcuts to websites (e.g., QR codes) or alternative means of selecting students (e.g., Random Name Picker). In all three cases, the teachers used the tools to substitute existing pedagogical practices in an attempt to promote teaching and learning processes (

Puentedura, 2006). The three teachers also leveraged the tools to encourage students’ participation and foster their collective intelligence (

Lankshear & Knobel, 2006).

The third type are tech-based environments and activities via digital platforms (e.g., Kahoot!, Nearpod, Quizlet, Edpuzzle, Quizizz, Mentimeter, Google Classroom), which serve multiple pedagogical functions to enable assessment, feedback, idea sharing and collaboration. Tec-based environments and activities not only help teachers to manage and organise their teaching practices; they also enable teaching and learning processes by gauging students’ prior knowledge and assessing their progress. Moreover, they facilitate self-paced learning and foster collaboration and creativity. Indeed, both Wendy and Liz adopted such tools to manage teaching logistics and design various digital tasks to teach different language skills and grammar. Moreover, Liz used them to promote creativity in drama production. Jack leveraged the tools to encourage both collaboration and creativity while tasking students with conducting research and presenting their topic. Critically, the tools enabled the teachers to extend learning beyond the classroom, with students engaging in the learning process both before and after class with the support of technology.

The fourth type are tech-based searching tools, which enable online research (e.g., Google Search) to engender different learning dynamics in classrooms. For example, the tools empowered students in Wendy’s and Liz’s classes to learn in a self-directed and autonomous manner throughout the writing process. They also allowed Jack’s primary students to conduct research with the help of tailor-made online materials and collaboratively create a multimodal text for presentation.

Finally, the fifth type is tech as content, which refers to the use of technological tools as teaching aids or topics for research and discussion. For example, Liz used an iPad as a prop in a drama scene, infusing ideas about how technology influences contemporary life into the production’s plot. Similarly, Jack used an iPad to introduce a class project about modern technology which resulted in Jack’s students thinking critically about how technology influences their lives. Following their presentations, they discussed with their classmates how to address the drawbacks of contemporary technologies.

5.6. Three Main Domains of Pedagogical Purposes Afforded by Technology

After examining the fundamental features, the technological tools used for the language-learning activities in each teacher’s lessons were analysed and evaluated to identify their pedagogical affordances. The pedagogical affordances of the technological tools in each case were then compared and contrasted with one another. Ultimately, three main domains of pedagogical purposes achieved through technology in ESL classes were identified. (For a summary of the analysis of the three domains of pedagogical purposes, see

Supplementary File S8.)

The first domain is achieving general pedagogical purposes. This refers to a teacher combining their technological and general pedagogical knowledge (

Shulman, 1986) to manage the class, organise teaching materials, encourage student participation and cater to learner diversity.

The second domain is teaching English language subject content, which refers to a teacher integrating technology to effectively promote students’ learning of English language content, language skills for communication and cultural and linguistic elements. This domain can be further subdivided into two areas. One is teaching conventional literacies, which refers to the use of technology to bolster the teaching and learning of various language skills as well as content in the curriculum for high-stakes testing. The other is teaching contemporary literacies, which refers to the teaching and learning of ever-changing literacy practices stemming from developments in technology and changes in culture. Examples of such literacy practices include those related to popular culture, English language arts, multiliteracies and new literacies.

The third domain is practising generic skills to promote teaching and learning, which refers to a teacher incorporating technology to create a learning space in which learners can use their English language knowledge by practising generic skills, such as critical thinking, creativity, collaboration and communication.

Figure 2 summarises the study’s findings, illustrating a typology of technology commonly used in ELT. The findings are further conceptualised to form a TPACK framework within ELT, thus demonstrating the interplay of ESL teachers’ TK, TPK, CK and TCK (as shown in

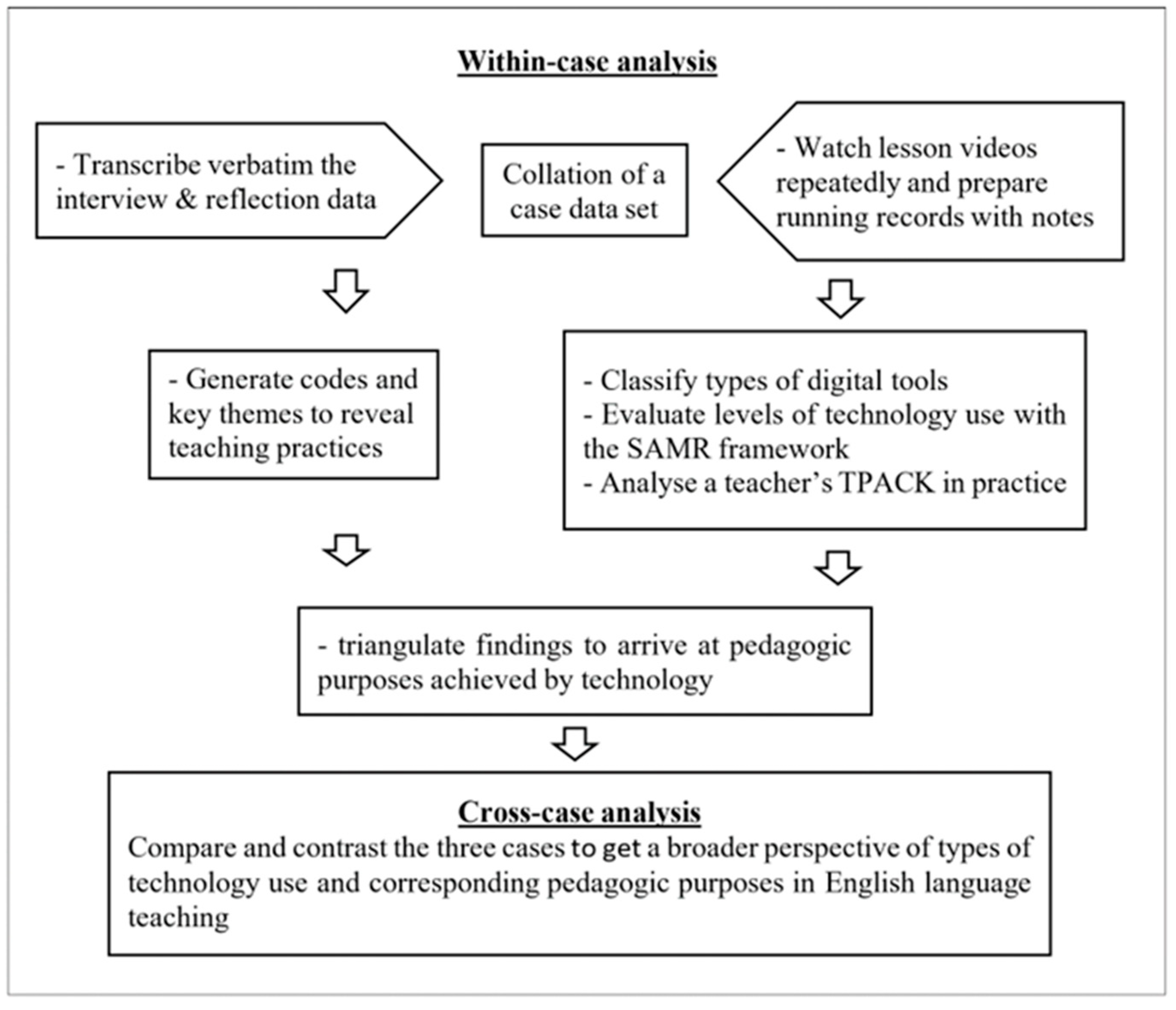

Figure 3).

6. Discussion

This study examined the technology-integration practices of three lead ESL teachers in three different Hong Kong schools to conceptualise a typology covering the features of five different types of commonly used technological tools (tech-based texts, tech-based functions via apps or online websites, tech-based environments and activities via platforms, tech-based searching tools and tech as content) and three domains of their pedagogical affordances (achieving general pedagogic purposes, teaching English language subject content and teaching conventional literacies). Based on the findings that stemmed from this typology, an improved TPACK-ELT framework was synthesised to deepen practitioners’ and researchers’ understanding of the relationship among various pieces of knowledge and skills when it comes to technology integration in ELT. The following subsections discuss the three domains of the pedagogical affordances in the typology, exploring their implications for teaching and learning the English language.

6.1. Technology Achieves General Pedagogical Purposes

The findings of this study show that technology was frequently used for general pedagogical purposes, such as motivating students, managing teaching logistics and encouraging participation. These results align with those of earlier studies (e.g.,

Boonmoh & Kulavichian, 2023;

Cepeda-Moya & Argudo-Serrano, 2022;

Dwiono et al., 2018;

Harmandaoğlu Baz et al., 2018;

Howlett et al., 2019), indicating that ESL teachers commonly integrate technology for relatively low-level purposes to replace conventional ways of organising teaching (

Puentedura, 2006).

Although this pedagogical purpose is inherently related to low-level technology integration (

Puentedura, 2006), it entails significant values in teaching and learning. The ethnographic findings of the three teachers’ cases indicate that this kind of technology integration can enhance the processes of teaching and learning in multiple ways. For example, a more technology-dense classroom setting can save class time by enabling teachers to more effectively organise classroom routines, such as taking attendance, following up on assignments and administering assessments (

Bebell & O’Dwyer, 2010). As a result of this increased logistical efficiency, more class time can be spent on other learning activities.

Moreover, as teachers increase the accessibility of learning materials (

Bax, 2003) and promote a more flexible educational environment (

Sung et al., 2016), students can obtain learning materials anytime and anywhere. Students’ different learning needs can be further catered to if teachers use technology to provide a tailored learning environment and enhance self-directed learning (

Golonka et al., 2014). Finally, educational technologies with appealing audio-visual effects and multiple interactive functions can make students more engaged and motivated to participate in learning activities (

Puentedura, 2013).

Therefore, on the one hand, ESL teachers in professional training workshops must be explicitly informed of the value of upgrading educational technologies for general pedagogical purposes. By explaining to ESL teachers how to manipulate the fundamental functions of useful technological tools, and by providing them with practical tips on how such manipulated functions achieve pedagogical effectiveness and efficiency across various situations in ELT contexts, workshop leaders can help teachers pick up the associated skills more quickly. Moreover, they would appreciate the time saved and the extended synchronous and asynchronous space for more meaningful learning activities both in and out of the classroom.

One the other hand, teachers must be urged to think critically about the use of technology and must be made to understand that its use is justified only for substitution of outmoded conventional pedagogical practices. Because developing teachers’ ability to use technology meaningfully is of paramount importance, training should also develop teachers’ knowledge and skills to integrate technology into teaching practice at higher levels of SAMR. For example, informed by Liz’s and Jack’s cases, teachers could design a collaborative project on a topic and teach students to use a combination of platforms and digital tools for online discussions and feedback before collaboratively writing online and constructing a PowerPoint presentation. Furthermore, to transform the traditional way of teaching reading and writing—for example, on a learning theme such as planets—instead of focussing on reading comprehension and writing by modelling, teachers can utilise virtual reality (VR) to let students interact with planetary objects and explore relevant details about planets through reading in a non-linear manner, thereby extracting useful information about a chosen planet to be used in a writing assignment (

Ahmet & Cavas, 2020).

In short, it will be beneficial for ESL teachers to know how to teach effectively in a technologised classroom and use technology to achieve pedagogical improvement.

6.2. Technology Enhances the Teaching of English Language Content

The findings show that technology facilitated the teaching of conventional literacies, thus aligning with the findings of prior studies (e.g.,

Bai et al., 2021;

Beach et al., 2010). For example, Wendy and Liz used online materials as teaching resources to facilitate students’ learning processes for various language skills. They also used various educational platforms and applications to teach vocabulary and grammar, assess students’ learning, provide feedback and track students’ progress.

The findings from the three cases revealed that multimedia resources contribute significant educational value in the form of engaging, interactive, meaningful and multimodal language resources. They offer students ‘a complex multi-sensory experience in exploring our world through the presentation of information through text, graphics, images, audio and video’ (

Thamarana et al., 2016, p. 15). Their affordances not only enrich the textbook-based curriculum in local contexts but also cater to students with different learning needs (

Muhartoyo & Aryusmar, 2022).

Moreover, the findings aligned with those of previous studies in that technology was used to introduce contemporary literacies, such as multiliteracies (

Kalantzis & Cope, 2015) and new literacies (

Lankshear & Knobel, 2006), that emerge from socio-cultural sources to link school learning to students’ real lives (e.g.,

Beach et al., 2010;

Wissman & Costello, 2014). For example, Jack infused contemporary texts (e.g., digital images, YouTube videos, websites) into a project-based module. He involved his students in consuming digital texts, prompting them to research tailor-made online resources and produce their own multimodal texts. Students learned actively by researching and co-constructing new knowledge about their research topics to be publicly shared and discussed further building on their critical thinking.

In fact, infusing new technologies and contemporary literacies into ESL education curricula can provide immense learning opportunities both in and out of the classroom. Innovative learning activities, such as digital games (e.g.,

Sykes, 2018), digital storytelling (e.g.,

Li, 2019), online comics (e.g.,

Saputri et al., 2021), video-making (e.g.,

Riyanto, 2020) and FanFiction (e.g.,

Bahoric & Swaggerty, 2015) can ‘provide transformative learning experiences for students in order to prepare for the changing socio-economic demands resulting from advances in information technology; these demands include the interpretation, use and production of materials for pleasure, study and work in the English medium’ (

CDC, 2017, p. 17).

The above discussion strongly suggests that schools and educators should review the content of existing ESL curricula in their schools, which are currently heavily reliant on the predetermined content of textbooks. They should concurrently revise and refine these curricula to align them with students’ evolving needs and interests. Additionally, some researchers have suggested that more multimedia resources should be used to provide thoughtful experiences to help students learn English. To enhance listening practice, for example, teachers can use online resources, such as YouTube videos and movie clips, to provide authentic listening materials with topics related to students’ lives (

Chhabra, 2012;

Pratama et al., 2020). They can also encourage students to listen to podcasts and revisit them at their own pace (

Yoestara & Putri, 2019) and even assign students to create collaborative podcast projects (

Ma’rufah et al., 2024) and vlogs (

Anrasiyana et al., 2023) to practice speaking.

Useful and user-friendly educational content authoring platforms, such as Canva, Google Sites and Book Creator, and digital teaching material builders, including Quizzes, Kahoot! and Google Forms, should be leveraged by ESL teachers and students to create teaching and learning materials (

Tomlinson, 2023). Moreover, new literacy practices, such as online comics and webpages, should be infused into English language curricula to offer opportunities for students to consume and produce modern, real-life literacies (

Lankshear & Knobel, 2006).

Moreover, as technology is integrated into ESL curricula, it must be meaningfully and purposefully embedded to ensure that teaching practices are effective and result in pedagogical improvements in learning (

Golonka et al., 2014). Finally, to ensure that ESL teachers are successful in their use of technology in teaching, schools should invest more resources in high-quality and consistent in-house professional development workshops to equip teachers with the knowledge and skills needed to teach with technology.

6.3. Technology Enhances the Practice of Generic Skills to Promote Teaching and Learning

Developing the generic skills of collaboration, communication, creativity and critical thinking is highly relevant to those learning the English language (

Trilling & Fadel, 2009). Under the methods of communicative language teaching (CLT) and the task-based language teaching (TBLT), ESL teachers aim to develop communicative competence (CC) (

Canale & Swain, 1980) among students to communicate effectively in their second language. To help students develop CC apart from fostering their grammatical competence (i.e., the ability to comprehend and use grammatically correct utterances in speech), ESL teachers also need to develop their sociolinguistic competence (i.e., the ability to use language appropriately across various social contexts), discourse competence (i.e., the ability to connect utterances to produce coherent speech or text) and strategical competence (i.e., the ability to use verbal and non-verbal resources and coping strategies to prevent breakdowns in communication). By designing language learning activities that encourage students to use generic skills, ESL teachers can help them to develop CC and prepare them for real-world challenges that they will encounter in the English language (

CDC, 2017).

This study’s findings show that technology enabled students to effectively work with one another through communication and collaboration, both in and out of the classroom. Through thoughtfully designed and technology-supported learning tasks, students were able to apply their critical thinking and creativity to learning processes. For example, Liz extended students’ learning out of the classroom to engage them in preparation work for a drama production. She leveraged technology to let her students engage in asynchronous online discussion, which also involved critical thinking in the process of decision-making. This after-class communication and collaboration heightened creativity during in-class preparation of scene backdrops as well as rehearsals of the drama production in the following lessons. This finding makes sense, as mobile internet access has been shown to significantly facilitate collaborative learning and enhance collective intelligence (

Lankshear & Knobel, 2006). Moreover, internet-enabled connectivity allows ESL teachers to design communicative and collaborative learning tasks both in and out of the classroom.

Although technology offers great affordances to aid ESL teachers in the development of students’ generic skills alongside their grammatical competence to enhance CC, it also requires teachers to be innovative and creative when designing suitable learning activities, and to ensure careful arrangement and supervision of the learning process. Lecture-based professional training may not be sufficient to help teachers develop the skills necessary to effectively incorporate generic skills into teaching. Thus, in-house learning communities should be established where teachers can meet regularly to share their teaching ideas and receive input from their colleagues and guest speakers. This kind of professional training enables exchanges between educators and grounded discussions about the actual implementation of activities.

To conclude this section, the use of technological tools to achieve different pedagogical aims pertaining to the teaching and learning of the English language depends on teachers’ pedagogical needs and vision of teaching. It also hinges on teachers’ creativity in lesson planning. This study offers a mere glimpse of the current uses of technology in ESL classrooms. More meaningful and constructive uses of technology may be seen in future teaching efforts as teachers obtain deeper knowledge about pedagogy and skills for technology integration.

8. Conclusions

As part of a more extensive study, this qualitative inquiry investigated the different types of technological tools used and their pedagogical purposes across the practices of three ESL teachers in Hong Kong classrooms. The study’s findings have notable pedagogical implications on which ESL teachers can reflect to consider how best to integrate technology into their teaching for various pedagogical purposes. In addition, the findings shed light on how new technologies can be incorporated into online education to enhance ELT in the post-COVID-19 period. It is hoped that the findings will help ESL teachers understand how to effectively leverage technology to achieve pedagogical improvements.

Despite its educational significance, this study features three significant limitations. First, data collection was limited to only one unit of work taught by each of the three teacher participants. Thus, the investigation of each teacher’s practices may not have been sufficiently thorough. Second, the study lacked students’ perspectives on the use of technology for pedagogical purposes. Therefore, future research should consider how both teachers and their students use technology for educational purposes with a longitudinal and ethnographic orientation (

O’Reilly, 2005;

Silverman, 2006). Doing so would provide a more holistic perspective on the use of technology to achieve pedagogical improvements. Third, this study was conducted in Hong Kong, a context with unique educational policies and cultural norms that limit its generalisability. However, its study context nonetheless provides valuable insights to understand how other similar high-stakes and exam-oriented education systems in Asia, such as Singapore, China and Taiwan, integrate technology in English language education. The findings of this study can also provide significant insights into how cultural and contextual factors, including teacher attitudes, student readiness and access to technology, influence technology integration in ELT. Therefore, comparative studies about technology integration in ELT across different regions are recommended to further illuminate universal principles and other context-specific challenges.