Abstract

Numerous studies support that the development of digital teaching competence is essential in 21st century schools. This paper examines Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) to gain a deeper understanding of ICT integration in teaching. By assessing TPACK, we uncover opportunities to enhance teacher competencies and, consequently, improve student learning. This research evaluated the initial TPACK of primary school teachers from a public school in the Colombian Caribbean. Eight teachers participated in a professional development program based on the Lesson Study (LS) methodology. Adopting an interpretive qualitative approach and a case study for the operational analysis of LS, the findings indicate that teachers, in self-reports and performance-based assessments, highlight high competence in the PK, CK, and PCK domains. This demonstrates their ability to select and adapt effective teaching strategies. They excel in guiding learning and understanding academic content, showcasing a remarkable capacity to adapt to the diverse socioeconomic realities of their students. However, these findings also highlight areas for improvement in developing the technological components of TPACK, specifically TK, TPK, TCK, TPCK, and XK.

1. Introduction

In the field of teacher training for the integration of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), three main challenges have been identified. Firstly, the incorporation of ICT in education initially promoted the creation of theories focused on pedagogical practices involving technologies. However, this process revealed a significant conceptual and practical disconnect, highlighting the gap between theoretical frameworks and their practical application in classrooms [1] Secondly, there has been a tendency to overvalue technical skills at the expense of pedagogy, the essential element of teaching [2]. This overemphasis on technical capacity undermines the importance of pedagogical strategies that are crucial for effective teaching [3]. Lastly, the curricular structures of teacher training programs often fail to align with the realities of school environments and the practical intentions of teachers. This misalignment results in a concerning disconnect between theory and practice, making it difficult for teachers to apply what they have learned in real-world classroom settings [4].

These findings underscore the necessity of developing a transversal model of ICT integration that harmonizes various theoretical perspectives and responds to the evolving demands of the educational context. Such a model would ensure that teacher training programs are both theoretically sound and practically relevant, bridging the gap between research and practice [5].

Significant contributions from researchers such as [6,7,8,9,10], have culminated in the development of the Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) model. This theoretical framework delineates the essential knowledge that teachers need to effectively integrate technology into their teaching practices. Since its inception, TPACK has become one of the most comprehensive models for assessing teaching competencies and understanding the dynamics of technology-mediated instruction. It maintains its relevance in contemporary education by offering a robust framework for the professional development of teachers, ensuring they are equipped with the skills necessary to navigate and utilize technological advancements in their teaching.

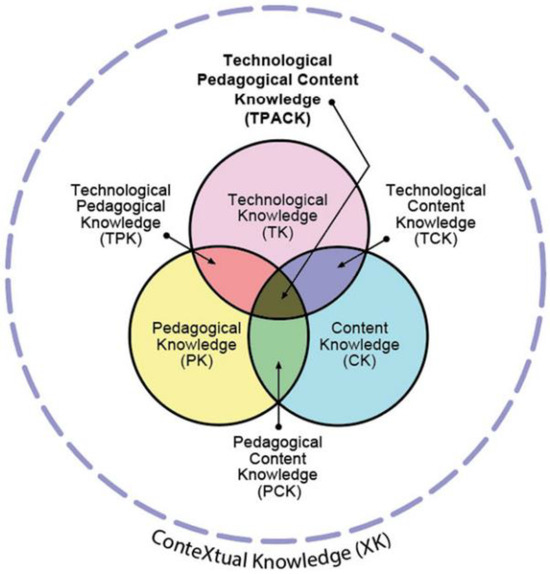

Mishra and Koehler structured the TPACK model into seven domains essential for effective teaching with technology [6]. This knowledge framework rests on three primary components: Pedagogical Knowledge (PK), encompassing a teacher’s ability to design meaningful learning environments; Content Knowledge (CK), referring to the teacher’s disciplinary expertise; and Technological Knowledge (TK), involving the selection and use of ICT. Additionally, the model incorporates four hybrid knowledge domains formed at the intersections of these components: Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK), Technological Pedagogical Knowledge (TPK), Technological Content Knowledge (TCK), and Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK). These hybrid domains describe how to effectively integrate technology into teaching. Furthermore, Mishra [11] included Contextual Knowledge (XK), associated with social, cultural, and institutional factors, which plays a crucial role in the effective application of the TPACK model (Figure 1). This knowledge ensures that technology integration is relevant and responsive to the specific needs of the learning environment.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of TPACK [11].

TPACK is most often assessed through self-report questionnaires [12]. These instruments are classified as general TPACK or specific to a particular technology, pedagogical approach, or content domain. To date, the literature distinguishes different types of instruments to measure TPACK that can be divided into two broad categories, namely, self-reports and those based on teacher performance [13]. In the first category, we find questionnaires (open and/or closed questions), evaluation scales, and interviews, which provide a detailed look at the teacher’s perception of their level of competence, their skills, identify their knowledge, and determine their challenges in relation to the integration of technologies into educational practice. On the other hand, performance-based assessments include the planning, implementation, and reflection of the process of teaching content. This implies the observation of teachers in real teaching situations. This may involve classroom observation, evaluation of recorded classes, interpretations of group discussions about evidence from a class, or review of digital portfolios showing examples of teaching activities with technology.

Some teacher training models have proven to be flexible and compatible with the different ways of assessing teachers’ TPACK [14,15]. In this context, LS emerges as a complementary approach that allows the development of the complexity and multidimensionality of technological competence. This training model not only allows a holistic assessment of TPACK but also offers educators the opportunity to develop skills and knowledge collaboratively, reflectively, and situated in the teacher’s own practice. This model contemplates several moments for the study of teaching and learning in which techniques and instruments can be used to assess TPACK from different dimensions.

The LS model, originally from Japan, encourages collective reflection and knowledge exchange among educators. This approach structures teacher learning in three crucial stages: collaborative lesson planning, which includes defining educational goals, choosing pedagogical strategies, deliberately incorporating technology, and considering contextual and student circumstances; the implementation and observation of teaching, where an educator applies the planned teaching strategies and technology while colleagues analyze the class and collect data on student experience and learning; and post-teaching reflection, focused on evaluating successful aspects and those that can be improved. This process culminates in the reconfiguration of lesson planning, providing a significant opportunity for TPACK advancement with the potential to enrich both teaching practice and student learning.

In the international context, LS in combination with TPACK has been used to assess and develop the integration of technologies in the classroom in pre-service, in-service, and continuing teacher education. For example, in Indonesia, there are works aimed at the development of TPACK in chemistry teachers for the teaching of electrolytes and non-electrolytes through LS [16]; in Thailand, LS combined with TPACK have been used to promote STEM education and 21st-century skills [17]; in the Philippines, research has been conducted on the effects of classroom study from active and passive microteaching (MLS) through the incorporation of technologies [18]; in Ireland, Marron and Coulter [19] aimed to evaluate TPACK through the use of iPads in the area of physical education. Huang et al. [20] appealed to the development of TPACK through an intercultural online LS between China and Australia; it was based on the expansive learning theory to examine the progress of teachers through various activities. These studies show the opportunities to learn to teach with technology; their importance lies in practical, reflective, collaborative development, instant feedback, and mutual learning among teachers.

In the post-pandemic context of Colombia, it is imperative that educators actively participate in a dynamic process of knowledge construction, motivated by the need to address emerging challenges. During the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers were forced to quickly adapt their teaching methods through the integration of information and communication technologies (ICT). However, the extent to which teachers and educational institutions responded to these challenges remained uncertain. Therefore, it has become essential to assess the state of TPACK to identify alternative and coherent strategies that improve technology-mediated pedagogical practices, facilitating the understanding of the structural concepts and knowledge that influence the ways of thinking and the practices of ICT integration by the teacher. Thus, the evaluation of TPACK in this study highlights various theoretical and methodological issues to answer the research question: What is the state of TPACK in a group of elementary school teachers?

This study focused on the evaluation of TPACK of elementary school teachers in an educational institution in the Colombian Caribbean. The objective was to evaluate TPACK to deepen the understanding of how ICT integration improves teaching. Through the combined use of TPACK and LS, opportunities to enhance teachers’ pedagogical skills are identified, which in turn contributes to the improvement of the students’ learning process.

The work context is the Edgardo Vives Campo District Educational Institution, a public entity established in 1954 as Escuela Libertador, located in locality 2: Rodrigo de Bastidas, Santa Marta, Colombia. During the 2023 academic period, the institution housed nearly 1500 students in three educational shifts. The school’s mission is to provide formal education that fosters the recognition and practice of universal rights and values, essential for social participation. In addition, it offers a specialization in tourism information, reflecting Santa Marta’s identity as a tourist destination. Socioeconomically, the educational community shows a medium level of vulnerability, with a diverse student population that includes Afro-Colombians, immigrants from neighboring countries, and students from dysfunctional families. This heterogeneity underscores a commitment to diversity and interculturality, while pedagogical methodologies promote an environment of respect and tolerance.

This study addresses a relevant gap in TPACK research by evaluating this framework in primary school teachers within a specific context of the Colombian Caribbean, characterized by a population in a situation of social vulnerability, diversity, and interculturality. While previous research exists on TPACK and Lesson Study, this study distinguishes itself by combining performance assessments and self-reports to evaluate the initial state of TPACK in in-service teachers. This approach provides a deep understanding of the strengths and areas for improvement in technology integration into pedagogical practice in this particular context. The scarcity of similar studies in the region and the need to identify coherent strategies to enhance technology-mediated pedagogical practices in vulnerable contexts highlight the relevance and necessity of this research.

2. Materials and Methods

This qualitative research adopted an interpretative perspective [21] to examine teaching within authentic classroom contexts. This approach is justified by the need to deeply understand teachers’ perceptions, experiences, and the meanings they attribute to integrating technology into their pedagogical practice. To achieve the research objectives, we implemented a collective case study design [22].

The collective case study design allows for a detailed and contextualized analysis of the TPACK phenomenon within a specific group of teachers, considering the particularities of their educational environment and the interactions that occur within it (see Appendix A). Combining the interpretative perspective and the case study design enables a holistic approach to the research subject, moving beyond mere data description and achieving a profound understanding of the dynamics underlying TPACK development within the specific context of primary schools in the Colombian Caribbean.

The relevance of case studies in research on teacher professional development and TPACK is supported by empirical evidence [19,20,23]. These studies demonstrate the usefulness of this approach for assessing and enriching teachers’ TPACK in real teaching and learning contexts.

The characterization of the case study, according to Stake’s [22] considerations, includes the following organization:

2.1. Case Selection

The collective case in this research was identified with the Greek letter Θ (capital theta) [22]. This case points to the interest in understanding and interpreting the initial state of the TPACK of a group of elementary school teachers based on their participation in a training strategy based on Lesson Study. On the other hand, the thematization is presented according to the knowledge of the TPACK as follows: ϑCK, ϑPK, ϑTK, ϑPCK, ϑTCK, ϑTPK, ϑXK, and ϑTPCK.

2.2. Unit of Analysis

This study aimed to gain an in-depth understanding of the TPACK knowledge of elementary school teachers at the IED Edgardo Vives Campo, adopting Stake’s [22] case study approach. All eight teachers at the school participated: seven women and one man, aged between 35 and 50, representing the entire elementary teaching staff. The selected curricular area was Spanish Language Arts, with the theme “narrative sequence” as the focus of the LS. Inclusion criteria considered teacher availability, academic qualifications, teaching experience, and knowledge of the social and institutional context. No teachers were excluded. Data collection primarily occurred through LS sessions, with teachers serving as primary sources of information, as suggested by Stake [22].

2.3. Techniques and Instruments

During each LS cycle, we employed various data collection techniques to evaluate teacher performance in relation to TPACK, including participant observation: we conducted systematic observations of LS planning and implementation sessions, documenting teacher interactions and decisions regarding technology use, pedagogy, and curricular content [22]; interviews: we conducted semi-structured individual interviews with each teacher, using a TPACK-based protocol to explore their perceptions of the model, their LS experience, and the challenges they faced; focus groups: we organized focus group sessions at the end of each LS cycle, involving all teachers (N = 8), to promote collective reflection on implemented practices and lessons learned; document analysis: we analyzed lesson plans, teaching materials, and student work generated during the LS, seeking evidence of TPACK in teaching practice; audiovisual recording: all LS planning, implementation, and reflection sessions were video recorded, focusing on teacher discussions and decisions as well as classroom activity implementation.

We systematically and coherently analyzed the data collected from these diverse sources. Audiovisual recordings, observation notes, interviews, and focus groups were transcribed and coded using a TPACK-based system. Document analysis focused on identifying TPACK-related evidence in lesson plans and teaching materials.

Data triangulation involved comparing and contrasting findings from different information sources, validating results, and gaining a deeper understanding of TPACK development in teachers throughout the LS cycle. Additionally, we used the adapted and validated TPACK questionnaire by Schmid et al. [10] to complement and triangulate qualitative findings, enriching data interpretation and offering a holistic view of the phenomenon. This questionnaire, comprising 32 items distributed across the eight TPACK knowledge domains (PK, TK, CK, PCK, TCK, TPK, TPCK, and XK), facilitated qualitative findings triangulation. The contextual component (XK), considered crucial by Mishra [11], was included in the analysis. The adapted questionnaire’s reliability was confirmed through Cronbach’s alpha (0.930) and McDonald’s omega (0.920).

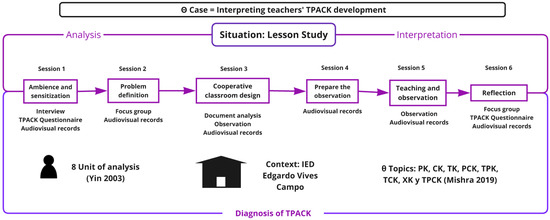

This approach, combining various techniques, ensured research rigor and validity, providing a comprehensive and contextualized understanding of TPACK development in participating teachers (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of the case.

2.4. Data Analysis and Interpretation

Within the interpretive framework, we employed Stake’s [22] categorical aggregation. Transcribed data from diverse sources (interviews, observations, focus groups, audiovisual recordings, and document analysis) were segmented and numbered into episodes. Following Perafán’s [24] definition, an episode represents the smallest unit of meaning extracted from teachers’ discourse, specifically a text fragment or recording related to TPACK knowledge. NVivo (version 14) was used for coding. We checked the correspondence of each defined code (PK, CK, TK, PCK, TPK, TCK, TPACK, and XK) with episodes derived from participants’ actions and discourse. Episodes were subsequently grouped into categories to analyze the status of each TPACK knowledge domain (see appendices). To organize, classify, and facilitate code identification, we established a specific nomenclature: Lesson Study cycle (cycle x), source instrument (interview), and episode number (episode x), forming a structure like “cycle 1/interview/episode 1.” For instance, an episode related to pedagogical knowledge could be coded as “cycle 1/interview/episode 7: ‘When we plan a class, the first thing we do is ensure that the strategies are didactic, interesting, and motivating for the students.’” Triangulation of data obtained through qualitative instruments was crucial for corroborating the coincidences and relevant findings during the episodes of the research experience.

Additionally, we conducted a descriptive statistical analysis of the TPACK questionnaire data using SPSS (version 25). We used the questionnaire results complementarily to enhance the rigor of the qualitative findings. This software generated tables displaying means and standard deviations, which we used to examine teachers’ perceptions in detail. We classified the results into descriptive levels based on the mean: superior (4.5 to 5), advanced (3.8 to 4.4), intermediate (3 to 3.7), basic (2.0 to 2.9), and insufficient (1 to 1.9), following Creswell [25].

2.5. Operational Process Combined Use of TPACK-LS

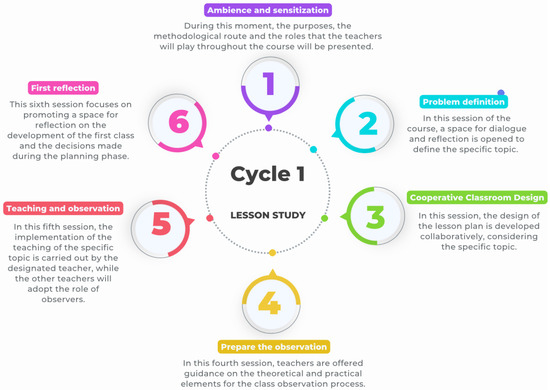

The operational process that included the combined use of LS presents the following training sessions with the teachers: 1. Setting and awareness; 2. definition of the problem; 3. cooperative lesson design; 4. prepare the observation; 5. teaching and observation; and 6. reflection: (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cycle 1 of the Lesson Study [26].

The initial session focuses on introducing the project to teachers and fostering discussion. It provides a platform for collective reflection on the challenges encountered when teaching specific content, identifying their root causes, and exploring potential solutions. In the second session, participants define the specific topic, which serves as the core content for lesson planning. In this instance, the chosen topic was narrative sequences. An inductive approach, aligned with the research context, is adopted, enabling teachers to identify, experience, and seek resolutions to relevant situations. Additionally, initial interviews and the TPACK questionnaire delve into the teachers’ academic backgrounds, professional experience, and perceptions regarding technology integration in education. The third session centers on collaborative lesson planning based on the specific topic. It encourages dialogue among teachers to establish curriculum criteria, assess student learning, and assign roles such as classroom observer and facilitator [26].

In the fourth session, a collective and dialectical analysis is carried out focused on observation and the identification of optimal strategies to document the crucial elements of the class. This stage seeks a mutual understanding of the methodology to comprehensively and meaningfully record the teaching experience. The fifth session is dedicated to the development of the class by the selected teacher, while the rest of the teaching staff is in charge of observing, listening, and collecting the relevant evidence of the session. Finally, the sixth session encourages critical reflection on the progress of the class and the strategic decisions made during planning, using an active discussion group that asks questions about the educational experience [26].

3. Results

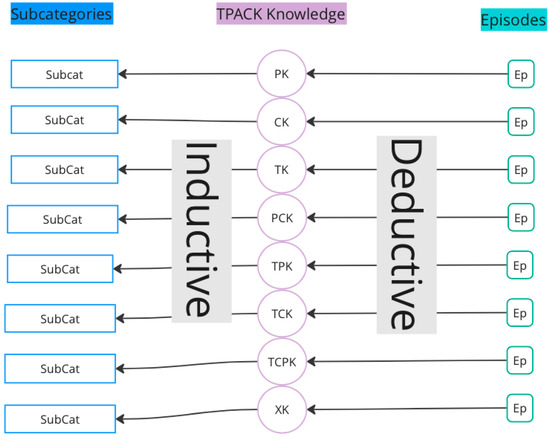

The initial analysis of teacher TPACK focuses on the evaluation of educators’ understanding and competencies regarding the incorporation of technology in their teaching during a cycle of LS training sessions. This process is crucial to discern strengths and detect possible improvements in TPACK. Through a panoramic review of the global data obtained from the episodes and the descriptive analyses of the TPACK questionnaire, together with a more exhaustive scrutiny of each TPACK knowledge in which emerging subcategories associated with these bodies of knowledge emerged (see Figure 4), the initial state of TPACK was interpreted.

Figure 4.

Interpretation process of subcategories.

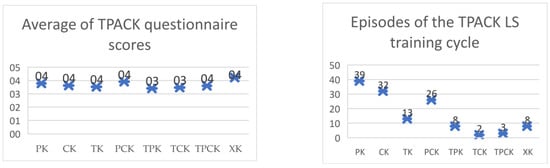

Figure 5 provides an overview of the participating teachers’ TPACK proficiency. It compares results from two data sources: first, the count of episodes related to TPACK knowledge domains, extracted from teacher performance assessments (interviews, observations, focus groups, document analysis, and audiovisual recordings); and second, the mean scores obtained from the TPACK questionnaire. This combined data analysis offers a panoramic view of the level of TPACK development in the participating teachers.

Figure 5.

Panoramic reading of the initial state of TPACK.

In the performance-based assessments during the LS training cycle (interviews, observations, focus groups, document analysis, and audiovisual recordings), we observed PK most frequently (39 episodes), followed by CK (32 episodes) and PCK (26 episodes). On the other hand, in the TPACK questionnaire results, teachers reported advanced levels in PCK and PK, with mean scores of 3.9 and 3.8, respectively. CK and TPCK followed closely with a mean score of 3.6. These two perspectives on the results highlight PK, CK, and PCK as the distinctive knowledge domains in the initial overall TPACK analysis.

The results indicate that the teachers’ TPACK is characterized by a repertoire of pedagogical competencies essential for the effective teaching of narrative sequences. These competencies include identifying relevant theories that underpin their teaching practice, applying diverse instructional strategies, designing curricula, structuring content, fostering students’ social-emotional development, and utilizing critical reflection for professional growth. We observed these competencies in specific episodes, as illustrated below:

PK: Cycle 1/interview/episode 19: “Well, I have read a lot about Emilia Ferreiro and Ana Teberosky’s work on the evolution of children’s written language, as well as Piaget’s stages of writing development.”

PCK: Cycle 1/interview/episode 11: “There are many didactics that one uses so that they can develop all their communication skills. Play is important, learning songs will give the child security, not only in acquiring knowledge but also in expressing their emotions and opinions.”

CK: Cycle 1/audiovisual recording/episode 2: “The sequence is very clear and that will lead them to discuss little, so we must think of something more complex.”

Significant variations are also observed associated with their competence in the management of various aspects of TPACK, with 39 episodes in PK, 32 in CK, and 26 in PCK, particularly in the teaching of narrative sequences. However, a marked disparity is detected in the knowledge associated with technology, evidenced by thirteen episodes in TK, only two in TCK, eight in TPK, and three in TPCK, which suggests an insufficient integration of technology in the pedagogical strategies of teachers.

Interpreting teachers’ initial knowledge necessitates a thorough exploration of the TPACK model components, identifying skills, competencies, and perceptions related to teaching narrative sequences in primary education. This analysis not only reveals the developmental level of PK, PCK, and CK but also allows us to pinpoint emerging subcategories in their teaching practice. Thus, we achieve a more comprehensive and detailed understanding of the teachers’ strengths and areas for improvement in content delivery.

Below are some results related to the most predominant knowledge and their distinctive subcategories:

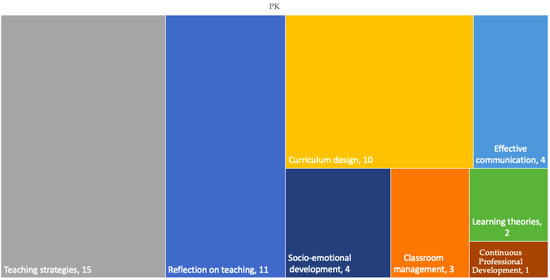

3.1. PK

During the LS training cycle, PK emerged as the most frequently cited component of the TPACK model, evident in 39 episodes, as shown in Figure 6. This pattern suggests that the teachers possess a strong theoretical and practical foundation, reflected in their competency in implementing teaching strategies (15 episodes), reflection skills (11 episodes), and curricular design abilities (10 episodes), all of which facilitate the learning of narrative sequences. Shulman [27] emphasizes the importance of educators understanding and applying effective instructional and curricular tactics that promote learning.

Figure 6.

PK subcategories.

Teaching strategies, integrated into teachers’ PK, are aligned with a collaborative approach and socio-critical pedagogy. This approach promotes the interconnection between critical reflection, effective collaboration, and socio-affective development, fundamental elements for the learning process. During the planning of the initial session, collaborative work was prioritized as an essential teaching strategy, reflecting the educators’ commitment to facilitating an environment that allows students to exhibit their competencies through participation in the proposed dynamics. Below are some episodes related to these approaches:

Cycle 1/interview/episode 15: “It would be didactics supported by the collaborative work approach because when we put them to work cooperatively we also strengthen other skills of the socio-affective part of the teamwork part when roles are assumed. That didactic in that Socio-critical approach in which this didactic of collaborative work is carried out is important, because using it currently, this teaches them to manage their role, to share with the other, to respect the opinion of the other, to lean on the other person.”

Cycle 1/interview/episode 5: “The way you present the activities and strategies in a didactic way that can be in the simplest theme, but if you present it to the student in a striking and meaningful way, they will feel motivated and learning will be more meaningful. So there are many strategies, but I say that the most important thing is to move the emotional part in the student.”

Episode “cycle 1/interview/episode 5” coincides with item PK 2 of the TPACK questionnaire (see Table 1); here it highlights how important it is for teachers to adapt their teaching style according to the characteristics of the students. This advanced level suggests a high predisposition to adjust their teaching strategy in a contextualized and flexible way. The standard deviation of 0.756 indicates that, although there is consistency in the responses, there are some teachers who assume the development of teaching in a generalized way without focusing on the particularities or individual differences of the students. Shulman [27] emphasizes that a key aspect of PK is the ability of teachers to adjust planning around the individual and collective needs of students.

Table 1.

PK results.

The initial PK analysis of teachers underscores the relevance of integrating collaborative and active methods into the educational environment. Strategies such as predicting learning and implementing songs and games are shown as didactic pillars. In addition, the assessment of errors and the emotional management of students, together with the random assignment of activities to encourage participation, emerge as distinctive elements in teacher reflections. Careful classroom management and meticulous planning, which include attention to the details of available resources, are essential. This set of factors related to PK reveals a systemic perspective that transcends the mere transmission of information, aspiring to develop emerging and contextualized strategies that lead to the training of analytical students committed to their education.

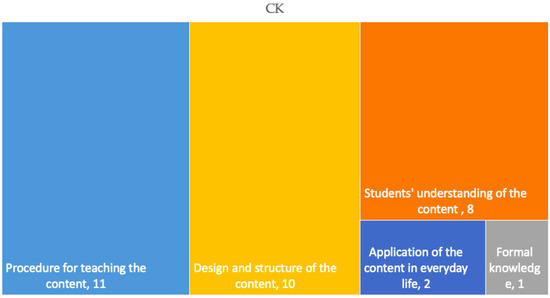

3.2. CK

Thirty-two episodes were identified within the CK component of the TPACK model, as shown in Figure 7. The subcategory “Procedures for teaching content” recorded the highest frequency with eleven episodes, followed by “Content design and structure” with ten. These findings indicate a tendency for educators to focus on the details and attributes of content during their teaching planning. Additionally, the subcategory “Students’ understanding of content” accounted for eight episodes, reflecting a significant interest in student perceptions of instructional material. According to Grossman [28], it is imperative that teachers have a deep and consolidated knowledge of the content to facilitate its transmission and ensure student understanding.

Figure 7.

CK subcategories.

The structuring of teaching content is crucial in the analysis of CK, highlighting the ability of teachers to adapt and organize activities linked to narrative sequences. This facilitates the creation of meaningful contexts that allow students to demonstrate their understanding, both orally and in writing. An illustrative episode of this process is the teacher planning on how to articulate the content of a narrative sequence for pedagogical purposes.

Cycle 1/interview/episode 8: “The narrative sequences, I evaluate the way in which the child coherently organizes the vignettes that are going to be presented to him or that he also has to generate an idea from the situation. That way of working would be both oral and written.”

The need to structure educational content in a meaningful way, as postulated by Ausubel [29], is fundamental for students to assimilate new knowledge. The prediction and evaluation by teachers of the organization of narrative sequences by students contributes to creating an environment conducive to the understanding of the teaching material. This perception of competence, reflected in the expressions of teachers during interviews, is aligned with the results of item CK 1 of the TPACK questionnaire (see Table 2), which indicates a self-recognition of an advanced level in the knowledge of the subject taught. According to Shulman [27], having a deep knowledge of the content taught in elementary education is crucial for effective teaching.

Table 2.

CK results.

Meticulous attention to detail in content design is a reflection of the teacher’s commitment to creating enriching educational experiences. The choice and presentation of visual and textual material during the educational process constitute crucial factors that influence students’ understanding of narrative sequences. Campo et al. [30] argue that an optimal configuration of content can enhance students’ understanding, providing complementary support to the verbal information provided by the educator, a perspective that teachers value when considering the impact of visual and textual resources in the construction of narrative sequences by students.

The CK of teachers is related to a comprehensive understanding of the varied structural aspects of educational content. This understanding is manifested in the ability to organize and present the content in a didactic way, which represents a significant facet of CK. It constitutes a critical moment for educators to anticipate and reflect on the impact that the structure and design of content have when interacting with students. Such a process involves the integration of practical experiences and life situations of the students, transcending the simple transmission of data. These considerations encourage teachers to critically evaluate their conceptual mastery of curricular content, an essential element that arises from reflection and is fundamental to the enrichment of teaching practice.

The analysis of the initial PK of teachers highlights the relevance of integrating collaborative and active methods in the educational environment. Strategies such as the anticipation of learning and the implementation of songs and games are shown as didactic pillars. In addition, the assessment of errors and the emotional management of students, together with the random assignment of activities to encourage participation, emerge as distinctive elements in teacher reflections. Careful classroom management and meticulous planning, which include attention to the details of available resources, are essential. This set of factors related to PK reveals a systemic perspective that transcends the mere transmission of information, aspiring to develop emerging and contextualized strategies that lead to the training of analytical students committed to their education.

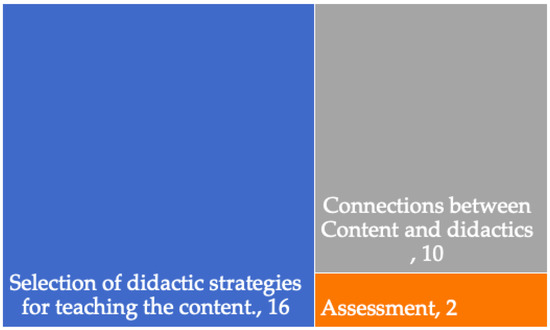

3.3. PCK

PCK accounted for 26 episodes (see Figure 8), emerging as a crucial TPACK component during the teaching of narrative sequences. The subcategory “Selection of instructional strategies for content delivery” stands out with 16 recorded episodes, suggesting teachers’ substantial dedication to choosing and applying pedagogical methods and approaches for teaching narrative sequences. Following closely, the subcategory “Connections between content and pedagogy” has 10 episodes, indicating a significant focus on teachers’ expressions and actions in relating the specific topic to classroom instruction. However, the subcategory “Evaluation” presents only two recorded episodes, potentially indicating less attention from teachers towards evaluation processes concerning narrative sequences.

Figure 8.

PCK subcategories.

Considering these points, we observed the teachers’ PCK through diverse strategies and approaches aimed at diversifying content delivery. Shulman [27] emphasized the importance of teachers adapting their instructional strategies to specific content for student comprehension. During planning, teaching, and reflection, some episodes highlight collaborative work, creative strategies, continuous assessment, and reflection on implemented strategies. We noted that teachers tend to organize academic work through student groups, promoting discussion and collaboration in organizing narrative sequences, as shown in the following episode:

Cycle 1/audiovisual recording/episode 1: “They can start right away with collaborative work. Each group receives a packet so they can include the texts that are on small pieces of paper, so they can order the sequence.”

This episode aligns with the advanced level of PCK 1 in the questionnaire, suggesting teachers’ strong ability to select appropriate teaching strategies for the classroom experience. Additionally, the standard deviation (0.354) indicates consistency in teachers’ perceptions when designing such activities during lesson planning. According to Shulman [27], this demonstrates a significant level of PCK development, enabling teachers to act critically when establishing creative strategies that lead students to decision-making—that is, thinking to apply their knowledge and learning (see Table 3).

Table 3.

PCK results.

Teachers’ thinking and actions in defining assessment activities also reflect a consistent PCK, as evidenced by their advanced level in item PCK 4 of the TPACK questionnaire. However, during performance-based assessment, we only found two episodes related to PCK assessment. In these episodes, teachers apply strategies to assess student comprehension, such as using formative assessment. This approach demonstrates pedagogical awareness tailored to teaching needs based on student understanding [27], as detailed below:

Cycle 1/observation/episode 5: “During individual work: We observed great willingness on the part of the children, their enjoyment of the work while handling materials and/or resources, and monitoring by the teacher. The teacher gave instructions for the activity, and although there was no paraphrasing by the children to ensure some level of understanding of what they were going to do, the objective of this first part was achieved.”

In the first cycle, PCK is characterized by teachers’ ability to apply strategies that facilitate understanding and assessment of learning. Teachers mention designing and implementing “creative” strategies, collaborative work, and motivation for participation to ensure uniformity and educational quality. They assess learning comprehension through games and songs, adopting a playful approach. Planning emerges as a key moment for discussion and reflection on variables and situations arising during interactive teaching.

3.4. TCK

Two significant episodes linked to TCK were detected, as shown in Figure 9. The first of these episodes affects the adaptation of technology to educational content, reflecting the ability to shape it to enrich pedagogical narratives. The second addresses the design of educational technology activities, implying a meticulous process of planning and developing technological tasks effectively. The scarcity of episodes in these categories suggests an opportunity for teacher professional development in the understanding and application of TPCK. This competence encompasses not only knowledge of technologies per se but also their ability to transform and improve the presentation of educational content, as stated by Koehler and Mishra [6].

Figure 9.

TCK subcategories.

The results obtained are aligned with the responses of all the items in the questionnaire associated with TCK, placing them at an intermediate level. Item TCK1 is notable, as seen in Table 4, which relates to teachers’ understanding of the influence of technological advances in their teaching area. This trend suggests a moderate recognition by teachers of the impact that new technologies have on educational content. Furthermore, a standard deviation of 0.463 reflects a homogeneous perception among teachers regarding this phenomenon.

Table 4.

TCK results.

It was observed that the implementation of narrative audios, specifically through the song “Chivita-Chivita,” facilitated the introduction of sequential concepts in the class. The students were induced to order events in which different animals were involved, thus promoting their initial understanding of sequences. According to the Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPCK) framework, the incorporation of this technological resource not only optimizes the transmission of information but also enhances the learning process [6]. A representative episode, extracted from the observation notes, is detailed, which illustrates the teacher’s use of the song to start the class activity.

Cycle 1/observation/episode 1: “The teacher uses a speaker to play the song “Chivita-Chivita” and the children sing with claps, some students present the animals of the song. It is evident that the students enjoy the moment, everyone sings the song.”

The implementation of auditory technologies in education offers an alternative methodology that facilitates learning through the reproduction of sound content, such as the song “Chivita-Chivita.” This strategy can provide multiple pedagogical advantages, including sensory stimulation and improvement in information retention through different perceptual channels, thus contributing to a more interactive and participatory learning environment. The episodes also show the need to design and adapt educational content implicit in songs for introductory activities, which shows a deficiency in TCK during teaching practices in the teaching of narrative sequences. It is urgent that educators develop skills to select and use technologies strategically, integrating them into all phases of the educational process, aligning them with learning objectives, and adjusting them to the specific needs and moments of teaching. According to Mishra and Koehler [6], strengthening TCK is crucial for a technologically integrated approach that is pedagogically meaningful. An episode is presented in which the teachers, during reflection, express the impact of having selected an inappropriate image found on the internet.

Cycle 1/focus group/episode 8: “Image number 5 had a difficulty, that image rotated here and there in the sequence, the students did not know where to put it. If that image had not been there, all the children would have done the sequence excellently, but this image that we took on a WEB was the one that we attached at the end and it influenced me a lot in the class.”

3.5. TPCK

TPCK was manifested in three episodes, which suggests limited integration and application of pedagogical, technological, and content knowledge in teaching practices, as illustrated in Figure 10. These episodes were classified into the subcategories of “pedagogical opportunities and limitations of technology” (two episodes), which reflect teacher awareness to identify obstacles in the adoption of technology in teaching and learning, and “design of learning environments with technologies” (one episode), which demonstrates how teachers apply their ability to design or structure learning situations enriched with ICT. Although these subcategories contribute to the enrichment of technological environments, the scarcity of related episodes in this cycle needs improvement in the teaching of narrative sequences. Koehler and Mishra [6] have highlighted the importance of TPCK for effective technology-based instruction, noting that current findings offer a formative opportunity for the professional advancement of educators. By recognizing the relevance of integrating this knowledge, essential elements for technological training are highlighted, allowing teachers to master the pedagogical use of technology in the classroom.

Figure 10.

TPCK subcategories.

Episodes identified within the LS cycle concerning TPACK correlate with the use of devices such as tablets and computers. However, the limited availability of these resources emerges as a significant constraint. This situation evidences a restricted understanding of TPCK by teachers, who often limit the technological integration in teaching to the use of computers and similar devices. It is necessary to overcome this gap, addressing technological barriers to maximize the use of all digital and non-digital tools in the educational process. In the following episode, it is observed that teachers’ understanding of TPCK is crucial for the effective teaching of narrative sequences, highlighting the importance of the use of technologies and interaction with digital activities.

Cycle 1/interview/episode 1: “Well, to teach with technology in a classroom, for me the ideal is that each child, at least, has a tablet or some computers. There they could interact because there are thousands of narrative sequences, there are thousands of interactive chips that they can work with. There are games, so I would say that the biggest limitation is the lack of technological resources, because as I told you before, we limit ourselves to the use of the video beam practically.”

Regarding teachers’ perceptions of TPCK, all items obtained an intermediate level (see Table 5), which indicates that teachers to some extent claim to have basic skills to use and apply technologies in order to improve teaching and learning. However, the high standard deviation suggests little consistency in teachers’ perceptions, given that possibly some teachers feel more confident and knowledgeable to be able to use technologies efficiently in the classroom.

Table 5.

TPACK results.

From a theoretical perspective, there is a correlation between the manifestations of TPCK in educators and Puentedura’s SAMR model [31]. The latter postulates that the goal of providing each student with technological devices corresponds to the Modification and Redefinition levels, which symbolize the most advanced phases of technological integration in education. Likewise, the adoption of innovative methodologies and technological tools underlines the commitment of teachers to the creation of learning environments that encourage active participation and interconnection with prior knowledge, crucial elements for the development of meaningful knowledge. It is important that these conceptual aspirations materialize in pedagogical practice appropriately and in accordance with the specific educational environment [32].

4. Discussion

The findings suggest that while teachers demonstrate a solid understanding of content and pedagogical strategies, the integration of technology into their teaching practice remains in its early stages. This gap in TPACK highlights the need to strengthen teacher training in the effective use of technology to enrich the learning experience. Adopting pedagogical strategies that incorporate technology more effectively could significantly enhance teaching and learning in contemporary educational settings [33].

The analysis of PK underscores the importance of incorporating collaborative and dynamic methods in education. Strategies such as anticipating learning, using songs and games, providing constructive feedback on errors, managing students’ emotions, and randomly assigning tasks to encourage participation are essential didactic foundations. Detailed classroom management and comprehensive planning, meticulously considering available resources, are crucial. Previous studies have emphasized the importance and diversity of actions that distinguish teachers’ PK during Lesson Study (LS), highlighting rich collaborative discussions on didactics and curriculum [16,23].

Regarding CK, it is observed that teachers’ deep understanding of the diverse structural aspects of educational content is vital. This understanding translates into the ability to organize and present content didactically, a crucial component of CK. Educators must consider and reflect on how content structure and design influence student interaction. Huang et al. [20] note that these actions not only prevent student misconceptions but also enhance teachers’ CK and contribute to the development of Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK), Technological Content Knowledge (TCK), and TPACK.

The distinction in teachers’ PK and CK knowledge during the experience fostered significant PCK development, enabling them to efficiently integrate didactic and disciplinary aspects for teaching narrative sequences. This approach demonstrates pedagogical awareness in tailoring instruction to students’ needs and understanding [27]. Reflection on the strategies used reveals significant aspects of teachers’ PCK, particularly when they recognize the importance of rethinking and adjusting instructional strategies based on content attributes, as evidenced in discussions about image selection and the need to redesign specific activities for deeper comprehension.

During the Lesson Study (LS) training cycle, aimed at answering the research question about the state of TPACK in in-service elementary school teachers, we detected few instances of teachers adapting educational content through technology use. This lack of technological integration in planning negatively impacted pedagogical effectiveness during the LS cycle and limited the development of a comprehensive TPACK vision. This situation is associated with the scarce findings related to technological knowledge: thirteen TK episodes, two TCK, eight TPK, three TPCK, and eight XK, reflecting insufficient contextual integration of the technological component in teachers’ pedagogical practice. A study by Monsalve-Suárez et al. [34] in Colombia also identified teachers’ difficulties in effectively integrating technology into curricular and didactic actions during the first LS cycle. However, in our experience, we observed a shift in the teachers’ mindset towards greater openness to technology during the reflection process.

The study findings reveal a significant area for growth in the development of the technological components of TPACK (T, TK, TCK, TPK, and TPACK) within the studied group of teachers. To foster improvement in these areas, we suggest implementing a new Lesson Study (LS) cycle. This cycle should promote the exploration and experimentation with various technological tools, along with their effective integration into lesson planning and execution, as indicated by Pérez and Soto [26]. Creating collaborative and reflective spaces for teachers, where they can update their technological and pedagogical knowledge and are encouraged to combine them creatively and innovatively in their teaching practice, will ultimately enrich the teaching and learning process for students.

In conclusion, our study underscores the need to assess TPACK holistically to enrich understanding and deeply identify teachers’ training needs. This approach profoundly unveils the distinctive attributes of each of the TPACK knowledge, validating the elements highlighted in the teachers’ performance assessment with the results of the TPACK questionnaire. These findings align with previous research contributions by several scholars [6,7,8] that highlight this complementary approach as the most comprehensive approach to assessing teacher competencies and understanding the dynamics of technology-mediated teaching in contemporary education.

This study underscores the importance of comprehensively assessing TPACK, particularly in educational settings with vulnerable and diverse populations. Our findings suggest that while teachers may possess strong pedagogical and content knowledge, the effective integration of technology into teaching remains a challenge. This highlights the need for future research to explore effective strategies for teacher professional development in technology, tailored to the specific needs and realities of these contexts.

Future Research Questions and Methods

What approaches to teacher professional development are most effective in enhancing the technological component of TPACK in vulnerable and diverse educational contexts?

How do specific contextual factors, such as the availability of technological resources and students’ socioeconomic levels, influence the development and implementation of TPACK in teaching practice?

What strategies can educational institutions implement to foster a culture of effective and sustainable technology integration in teaching?

Future research could employ mixed methods, combining questionnaires, observations, interviews, and product analysis (e.g., lesson and unit plans) to gain a deep understanding of TPACK development processes and their impact on teaching practice and student learning. Longitudinal studies would also be valuable for assessing the sustainability of professional development interventions and their long-term impact on technology integration in teaching.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Á.J.S. and J.O.I.; methodology, A.P.-R.; software, Á.J.S.; validation, Á.J.S., J.O.I. and A.P.-R.; formal analysis, J.O.I.; investigation, A.P.-R.; resources, Á.J.S.; data curation, A.P.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.O.I.; writing—review and editing, A.P.-R.; visualization, J.O.I.; supervision, Á.J.S.; project administration, J.O.I.; funding acquisition, Á.J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Vice-Rector’s Office for Research at the Universidad del Magdalena: “Desarrollo del TPACK en profesores en servicio: curso de formación docente TPACK-LS:” VIN2023188.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participants approved an informed consent and data transfer document.

Informed Consent Statement

It was governed by ethical principles to guarantee the social welfare of the teachers involved. Fundamental aspects such as acquiescence, trust, confidentiality, and protection of information against possible risks were considered. In addition, informed consent was obtained, reflecting the voluntary acceptance of the teachers, who were duly informed of the details of the study and the activities involved.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors of this article declare that they have no financial or personal conflicts of interest in relation to the work presented.

Appendix A

| Code | Episodes | Episode Nomenclature | Number of Episodes Identified |

| PK | “When we plan a class, the first thing is to make sure the strategies are didactic, interesting, and motivating for the students.” | Cycle 1/interview/episode 7 | 39 |

| CK | “The children socialized their sequences and read the labels. The teacher insistently stated that there was no problem if they made a mistake.” | Cycle 1/observation/episode 2 | 32 |

| TK | “The educational platforms, which provide us with a whole range of tools for teachers and which continue to be explored, such as Word, which other one was the one I used? Those were the ones I used the most: Quizziz, which is also a tool to make evaluations or to give feedback, and Youtube, which uses videos.” | Cycle 1/interview/episode 1 | 13 |

| PCK | “This could be a suggestion to rethink the strategies, that they put together puzzles, but from the text of the narrative sequence, without an image to see how much they understood.” | Cycle 1/focus groups/episode 4 | 26 |

| TPK | “Projecting stories on videos so that they can understand and stimulate the answers to certain questions regarding the story.” | Cycle 1/interview/episode 2 | 8 |

| TCK | “The teacher plays the song chivita- chivita and the children sing along with clapping, some students present the sequence of the animals in the song.” | Cycle 1/observation/episode 1 | 2 |

| TPCK | “Well, to teach with technology in a classroom, for me the ideal is for each child to have at least a tablet or to see computers, so that each child has access to a computer. Then they could interact with the narrative sequences through games” | Cycle 1/interview/episode 1 | 3 |

| XK | “During teamwork: the classroom area made it somewhat impossible to organize the teams.” | Cycle 1/observation/episode 2 | 8 |

| Explanation code: represents the TPACK knowledge domain to which the episode is associated (PK, TK, CK, PCK, TCK, TPK, TPACK, XK). Episode: contains the textual or audiovisual description of the fragment related to the TPACK knowledge. Episode nomenclature: follows the format “cycle x/instrument/episode x” for precise identification. Number of episodes: counts how many similar episodes were identified in the cycle. | |||

References

- Angeli, C.; Valanides, N. Epistemological and methodological issues for the conceptualization, development, and assessment of ICT–TPCK: Advances in technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK). Comput. Educ. 2009, 52, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquerizo Álava, V.; Fernández-Márque, E.; Morales Cevallos, M.B.; López Meneses, E. Digital organizational culture and online digital educational coaching: A meta-analysis study in the field of Social Sciences. Innoeduca Int. J. Technol. Educ. Innov. 2024, 10, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabero-Almenara, J.; Guillén-Gámez, F.D.; Ruiz-Palmero, J.; Palacios-Rodríguez, A. Teachers’ digital competence to assist students with functional diversity: Identification of factors through logistic regression methods. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2022, 53, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, J.M. El conocimiento tecnológico pedagógico de contenido (TPCK): Un análisis a partir de la relación e integración entre el componente tecnológico y conocimiento pedagógico de contenido. Tecné Epistem. Y Didaxis TED 2020, 47, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Tena, R.; Barragán-Sánchez, R.; Gutiérrez-Castillo, J.J.; Palacios-Rodríguez, A. Análisis de la competencia digital docente en Educación Infantil. Perfil e identificación de factores que influyen. Bordón. Rev. De Pedagog. 2024, 76, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M.J. Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2006, 108, 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doering, A.; Veletsianos, G.; Scharber, C.; Miller, C. Using the technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge framework to design online learning environments and professional development. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2009, 41, 319–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tee, M.Y.; Lee, S.S. From socialisation to internalisation: Cultivating technological pedagogical content knowledge through problem-based learning. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2011, 27, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Niess, M.L. Introduction to teachers’ knowledge-of-practice for teaching with digital technologies: A technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) framework. In Teacher Training and Professional Development: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; Management Association, Ed.; IGI Global: Boston, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 145–159. Available online: https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/introduction-to-teachers-knowledge-of-practice-for-teaching-with-digital-technologies/203175 (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Schmid, M.; Brianza, E.; Petko, D. Developing a short assessment instrument for Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK.xs) and comparing the factor structure of an integrative and a transformative model. Comput. Educ. 2020, 157, 103967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P. Considering Contextual Knowledge: The TPACK Diagram Gets an Upgrade. J. Digit. Learn. Teach. Educ. 2019, 35, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabero-Almenara, J.; Pérez-Díez De Los Ríos, J.L.; Llorente-Cejudo, C. Estructural equation model and validation of the TPACK model: Empirical study. Profesorado 2018, 22, 353–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisser, P.; Voogt, J.; van Braak, J.; Tondeur, J. Measuring and assessing Tpack (Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge). In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Technology; Spector, J.M., Ed.; 2015; pp. 489–492. Available online: https://sk.sagepub.com/reference/the-sage-encyclopedia-of-educational-technology/i6628.xml (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Ladrón, L.; Almagro, B.; Cabero Almenara, J. Cuestionario TPACK para docentes de Educación Física. Campus Virtuales 2021, 10, 173–183. Available online: https://idus.us.es/bitstream/handle/11441/104715/1/TPACK.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Jiménez, Á.A.; Ortega, J.M.; Cabero-Almenara, J.; Palacios-Rodríguez, A. Development of the teacher’s technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) from the Lesson Study: A systematic review. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1078913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anci, F.F.; Paristiowati, M.; Budi, S.; Tritiyatma, H.; Fitriani, E. Development of TPACK of chemistry teacher on electrolyte and non-electrolyte topic through lesson study. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2021; Volume 2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamrat, S.; Apichatyotin, N.; Puakanokhirun, K. The use of high impact practices (HIPs) on chemistry lesson design and implementation by pre-service teachers. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 1923, 30009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danday, B.A. Active vs. Passive microteaching lesson study: Effects on Pre-service Teachers’ Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2019, 18, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marron, S.; Coulter, M. Initial teacher educators’ integrating iPads into their physical education teaching. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2021, 40, 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lai, M.Y.; Huang, R. Teachers’ learning through an online lesson study: An analysis from the expansive learning perspective. Int. J. Lesson Learn. Stud. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, F. Metodos Cualitativos de Investigación sobre la Enseñanza. [Recurso electrónico]/F. Erickson; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1989; Available online: https://indaga.ual.es/discovery/fulldisplay/alma991001577849704991/34CBUA_UAL:VU1 (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Stake, R. Investigación con Estudio de Casos; Universidad de Zaragoza: Morata, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Paristiowati, M.; Yusmaniar Fazar-Nurhadi, M.; Imansari, A. Analysis of Technological Pedagogical and Content Knowledge (TPACK) of Prospective Chemistry Teachers through Lesson Study. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1521, 042069. [Google Scholar]

- Perafán, G. Pensamiento Docente y Práctica Pedagógica: Una Investigación Sobre el Pensamiento de los Docentes; Editorial Magisterio: Bogotá, Colombia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; University of Nebraska–Lincoln: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; Available online: https://repository.unmas.ac.id/medias/journal/EBK-00121.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Pérez, Á.I.; Soto, E. Lesson Study, Investigación acción cooperativa para formar docentes y recrear el curriculum. Rev. Interuniv. De Form. Del Profr. 2015, 84, 138. Available online: http://www.aufop.com/aufop/uploaded_files/revistas/127929800810.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Shulman, L.S. Those who understand: Knowledge Growth in teaching. Am. Educ. Res. Assoc. 1986, 15, 4–14. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1175860 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Grossman, P. The Making of a Teacher: Teacher Knowledge and Teacher Education. J. Teach. Educ. 1991, 42, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausubel, D.P. Psicología Educativa. Un Punto de Vista Cognoscitivo; Ed. Trillas: México, Mexico, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Campo, R.; Hernandez-Serrano, M.J.; Renes-Arellano, P.; Lena-Acebo, F.J. Los Recursos Educativos Abiertos adaptados a estilos de aprendizaje en la enseñanza de competencias digitales en educación superior. Revista de Estilos de Aprendizaje. 2023, 15, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puentedura, R. Building Transformation: An Introductionto the SAMR Model. 2014. Available online: http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/2014/08/22/BuildingTransformation_AnIntroductionToSAMR.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Palacios-Rodríguez, A.; Guillén-Gámez, F.D.; Cabero-Almenara, J.; Gutiérrez-Castillo, J.J. Teacher Digital Competence in the education levels of Compulsory Education according to DigCompEdu: The impact of demographic predictors on its development. Interact. Des. Archit. (S) J.-IxDA 2023, 57, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Cruz, I. Effect of virtual teaching on university academic performance: A Difference in Difference regression analysis. Pixel-Bit. Rev. De Medios Y Educ. 2024, 70, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsalve-Suárez, J.C.; Polo-Rueda, S.P.; Ruiz-Lacouture, A.C.; Ortega-Iglesias, J.M. Modelo TPACK y la Lesson Study para desarrollar la comprensión lectora en la básica primaria. Folios 2024, 59, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).