Abstract

Outdoor recreational activities offer critical benefits to youth development, yet their impacts have been insufficiently synthesized. This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the effects of outdoor recreation on children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 years. Significant improvements were observed in psychological well-being, social connectivity, and environmental awareness, emphasizing the multidimensional benefits of such activities. Challenges such as urbanization and reduced access to green spaces highlighted the need for prioritizing outdoor engagement to counteract the growing detachment from nature. This study followed PRISMA guidelines and included 21 studies published between 2014 and 2024. A random-effects meta-analysis revealed positive effects on mood, anxiety reduction, interpersonal relationships, and environmental responsibility. However, significant heterogeneity reflected variability in study designs and contexts. The GRADE framework assessed evidence certainty, rating psychological benefits as moderate, social connectivity as high, and environmental awareness as low. Limitations included reliance on self-reported data and exclusion of pandemic-era studies. These findings emphasized the role of outdoor activities in addressing modern challenges such as urbanization and climate change by fostering holistic youth development. Policymakers and educators should be encouraged to integrate outdoor programs into curricula and community initiatives to promote mental health, social cohesion, and environmental stewardship.

1. Introduction

Outdoor recreation has been extensively studied for its psychological, social, and environmental contributions to well-being (Puhakka, 2021; Zwart & Ewert, 2022). These activities fostered physical and emotional health, promoted social interactions, and cultivated a sense of environmental stewardship (Manferdelli et al., 2019; Zafeiroudi & Hatzigeorgiadis, 2014). However, as urbanization accelerated, and children spent less time in natural settings, it became increasingly urgent to reconnect young people with outdoor environments to counteract the growing detachment from nature and its associated consequences on health and development (Loebach et al., 2021; Sefcik et al., 2019). The reduction in green space availability limits opportunities for outdoor engagement, contributing to a growing detachment from nature and its associated consequences on health and development.

Outdoor recreation encompasses a diverse range of activities, including structured and unstructured engagements with natural environments (Meeks & Mauldin, 1990). Structured outdoor activities, such as guided environmental education programs, organized adventure courses, and team sports, involve planned, goal-oriented participation. In contrast, unstructured outdoor play—such as free play in green spaces, exploration, and spontaneous social interactions—allows for more self-directed engagement with nature (Dankiw et al., 2020). Structured play provides goal-oriented benefits, helping children develop specific skills, discipline, and teamwork through organized activities such as sports and guided learning programs (Lee et al., 2020). In contrast, unstructured play fosters creativity, independence, and social negotiation by allowing children to explore and engage in spontaneous, self-directed activities (Zafeiroudi, 2021; Zafeiroudi & Kouthouris, 2021). While structured play ensures skill development in a controlled environment, unstructured play enhances emotional resilience, problem-solving, and adaptability, making both essential for well-rounded development. Additionally, unstructured play encourages a deeper connection with nature, as children freely explore their surroundings, fostering environmental appreciation and potentially promoting sustainable behaviors (Lee et al., 2020).

Outdoor activities such as hiking, nature exploration, and environmental education offer unique, multidimensional benefits that extend beyond physical health (Kiviranta et al., 2024). It has been demonstrated that these activities have the capacity to support psychological resilience by mitigating stress and anxiety through restorative interactions with natural settings (Buchecker & Degenhardt, 2015). Furthermore, they foster social cohesion, with structured group activities enhancing teamwork, communication, and interpersonal relationships (Cooley et al., 2015; Roux & Janse Van Rensburg, 2019). Importantly, outdoor engagement also cultivates environmental stewardship, instilling pro-environmental attitudes and sustainable behaviors critical for addressing contemporary ecological challenges (Harbrow, 2019; Zafeiroudi, 2014). Despite these potential benefits, existing research is fragmented, with significant variability in study designs, populations, and outcomes, creating barriers to a comprehensive understanding of their impacts. In recent years, studies examining outdoor recreation across different geographical and cultural contexts have contributed to the understanding of its diverse impacts. However, there remains a gap in synthesizing these findings to identify potential variations and commonalities in how outdoor activities influence youth development. Addressing this gap is essential for developing globally relevant policies and interventions that promote outdoor engagement across diverse populations. This emphasizes the need for a precise synthesis of evidence to elucidate the psychological, social, and environmental contributions of outdoor recreation to youth development and to inform evidence-based interventions and policies.

This study focused on children and adolescents, a group uniquely positioned at a formative stage of life. Childhood and adolescence represented critical periods for developing habits and attitudes that often persisted into adulthood (Lawler et al., 2017). Evidence suggested that outdoor activities during these years improved mental health, fostered social skills, and instilled environmental responsibility (Fromel et al., 2017; Grigoletto et al., 2022). Despite this, existing research often lacked a comprehensive synthesis of the diverse benefits of outdoor recreation across varied contexts and populations, leaving gaps in understanding its full potential.

The importance of the present review and meta-analysis was further highlighted by contemporary challenges. Increasing urbanization led to a decline in accessible green spaces, reducing opportunities for outdoor engagement. Simultaneously, the effects of climate change demanded adaptive approaches to ensure outdoor activities remained safe and accessible (Schneider et al., 2024). Addressing these challenges required a systematic understanding of how outdoor activities benefited young people and how such benefits could be maximized through informed policies and educational programs.

The present study aimed to fill these gaps by synthesizing the existing literature on the psychological, social, and environmental benefits of outdoor recreation for children and adolescents. By examining studies across diverse contexts and employing robust methodological criteria, it sought to provide actionable insights for educators, policymakers, and researchers. Specifically, the review addressed three core questions:

- What psychological benefits did outdoor activities offer?

- How did they foster social connections?

- And what role did they play in promoting environmental awareness?

By answering these questions, this study contributed to the broader understanding of outdoor recreation’s multifaceted impact on youth development, offering a foundation for future research and practical applications in education and community planning.

2. Materials and Methods

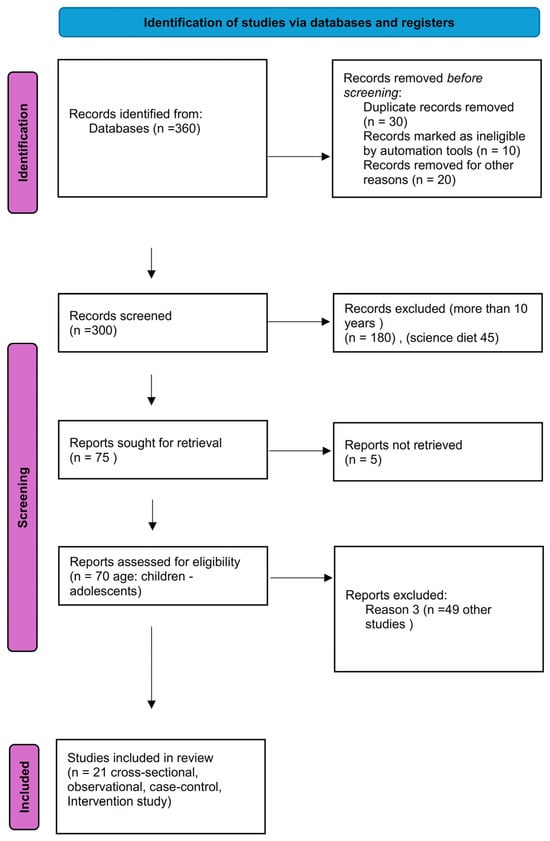

This systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to ensure a rigorous and transparent process (Frumkin et al., 2017). A detailed PRISMA flow diagram was used to document the identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion stages. The review was registered with PROSPERO under ID 636831 on 10 January 2025.

The literature search was performed across three major online databases: PubMed, Google Scholar, and EBSCO. These databases were selected for their extensive coverage of biomedical, social science, and interdisciplinary research. The search included studies published between January 2014 and April 2024. A combination of keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms was used, including “outdoor recreation”, “adolescents”, “social benefits”, “mental health”, “environmental responsibility”, and “well-being”. For example, (“outdoor recreation” OR “nature engagement”) AND (“children” OR “adolescents”) AND (“psychological well-being” OR “mental health” OR “social connectivity” OR “environmental responsibility”) was used for Google scholar. The search strategy was iteratively refined through pilot searches to ensure comprehensive retrieval of relevant studies. Additionally, the reference lists of included articles were screened for further relevant studies.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were meticulously developed to ensure the selection of studies aligned with the research objectives and maintained high methodological standards. The eligibility criteria for this systematic review were structured using the PICOS framework to ensure clarity and consistency in study selection. The population included children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 years, reflecting the target demographic for understanding the benefits of outdoor recreational activities during formative developmental stages. The interventions considered were outdoor recreational activities such as hiking, nature engagement, green space usage, team sports, and environmental education programs. To facilitate meaningful comparisons, the comparators included groups not participating in outdoor activities, alternative interventions such as indoor activities or other wellness programs, or no intervention.

The outcomes of interest were categorized into three key areas: psychological benefits, such as improved mood and reduced anxiety; social connectivity, including strengthened interpersonal relationships and group dynamics; and environmental awareness, exemplified by sustainable behaviors and deeper connections with nature. Regarding the study design, only quantitative or qualitative studies published in peer-reviewed scientific journals between 2014 and 2024 were eligible, provided they were written in English.

Studies were excluded if they focused exclusively on clinical populations or specific medical cases, as these groups fell outside the scope of the general youth population. For this study, clinical populations were defined as individuals diagnosed with psychiatric, neurological, or chronic physical conditions requiring specialized medical interventions. This exclusion was made to ensure that the findings reflect the effects of outdoor recreation on the general youth population rather than interventions specifically designed for therapeutic or rehabilitative purposes. Additionally, review articles, theoretical and unpublished papers, and non-empirical studies were excluded to maintain a focus on primary data. Studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022) were also excluded to avoid confounding variables related to lockdowns and altered methodologies, such as remote surveys or retrospective reporting.

3. Results

The study selection process followed the PRISMA guidelines to ensure a transparent and systematic approach. The process included the identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion stages, as outlined below (Figure 1). First, a comprehensive search was conducted across databases. This search initially identified a total of 360 records. After removing duplicate entries, 270 unique records remained eligible for further assessment.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

In the second step, the titles and abstracts of the 270 unique records were screened for relevance. Studies were excluded if they did not focus on outdoor recreational activities, did not involve children or adolescents as the primary population, or lacked data on psychological, social, or environmental benefits. This screening narrowed the pool to 70 articles regarded potentially eligible for inclusion.

In the final step, full-text versions of the 70 articles were retrieved and evaluated against predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. To be included, studies had to focus on children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 years, provide empirical data or theoretical insights on the psychological, social, or environmental benefits of outdoor activities, and be published in English in peer-reviewed journals between 2014 and 2024. Articles were excluded if they focused on clinical populations or specific medical cases or if they lacked sufficient data on the outcomes of interest. The reasons for exclusion were meticulously documented. Ultimately, 21 studies met all criteria and were included in the systematic review (Figure 1).

For each included study, data were systematically extracted to ensure comprehensive and consistent analysis. General information was collected, including the authors, year of publication, and the country where the study was conducted. Study characteristics, such as the study design, sample size, population demographics, and context, were also recorded. Detailed descriptions of the outdoor recreational activities and the tools or metrics used to assess outcomes were noted under interventions and measurements. Finally, key findings related to the psychological, social, and environmental benefits observed in participants were extracted.

The quality of the selected studies was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool, which focused on several domains to ensure rigor. These included the appropriateness of the randomization methods, the completeness and transparency of data collection processes, the management of incomplete data and mitigation of potential biases, and the clarity and comprehensiveness in reporting results. Based on these assessments, studies were categorized as having a low, moderate, or high risk of bias. Only studies identified as low-risk were included in the quantitative analysis to ensure reliability and validity.

The analysis integrated both quantitative and qualitative approaches to provide a holistic understanding of the data. For the quantitative analysis, statistical methods were conducted using JASP 0.19.0 software. A random effects model was applied to synthesize the quantitative data and calculate overall effect sizes. Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran’s Q and Higgins’ I2 indices (Table 1), with findings indicating significant heterogeneity among the studies included.

Table 1.

Estimates of residual heterogeneity.

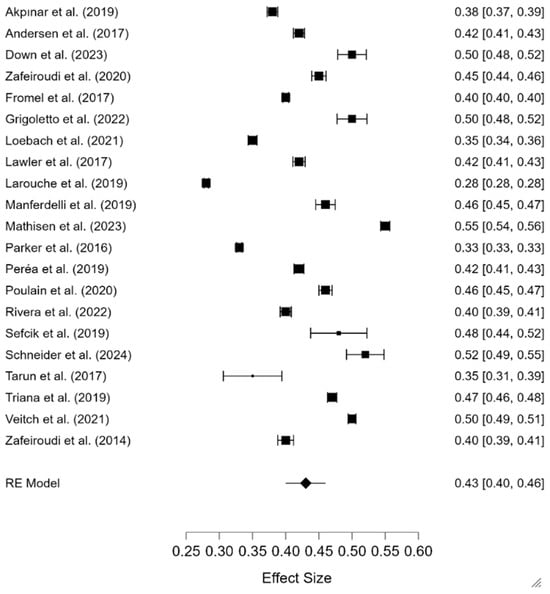

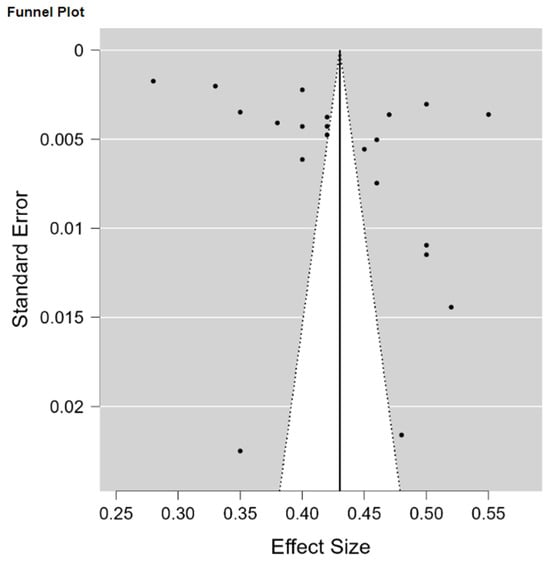

The quantitative analysis focused on calculating the overall effect size using a random effects model to synthesize findings. Statistical heterogeneity was thoroughly evaluated to ensure the reliability of the meta-analysis. Cochran’s Q was calculated at 9614.110 (df = 21, p < 0.001) (Table 2), indicating significant heterogeneity among the included studies. Similarly, Higgins’ I2 was calculated at 99.688%, suggesting that variations in effect sizes were primarily attributable to methodological and contextual differences. Additionally, τ2 (Tau-squared) was estimated at a high value, further confirming the heterogeneity of the data. These results suggested variability among the studies included in the meta-analysis. To assess publication bias, a Funnel Plot was generated, which demonstrated symmetry, indicating a low likelihood of bias in the selection and reporting of studies. The Forest Plot (Figure 2) further supported these findings by illustrating a convergence of effect sizes around the overall estimate, reinforcing the homogeneity and reliability of the meta-analysis results.

Table 2.

Statistical results of fixed and random effects models.

Figure 2.

Forest Plot: Effect sizes and confidence intervals.

For the qualitative analysis, a thematic approach was used to organize findings into key themes. These themes included psychological well-being, focusing on reductions in anxiety and improvements in mood; social connectedness, emphasizing strengthened interpersonal relationships and enhanced group interactions; and environmental awareness, highlighting a deepened connection with nature and the fostering of sustainable behaviors. By integrating both analytical approaches, this methodology ensured a comprehensive synthesis of evidence on the benefits of outdoor recreational activities for children and adolescents.

The results for the fixed and random effects models are presented in Table 2. Cochran’s Q test (Q = 9614.110, df = 21, p < 0.001) indicated significant heterogeneity, which highlighted variability among the included studies. The Omnibus test of Model Coefficients is statistically significant (Q = 824.334, p < 0.001), confirming the overall significant effect of the factor tested. This suggested that the random effects model was appropriate for synthesizing the data (Table 2).

Table 3 provides the estimates of the coefficients derived from the meta-analysis. The overall effect size was calculated at 0.430 (95% CI: 0.401–0.460), with a p-value of <0.001, indicating a statistically significant positive impact. The low standard error (0.015) highlighted the precision of the estimate, while the high z-value (26.711) further affirms its statistical robustness. Collectively, these results substantiate the reliability and validity of the findings.

Table 3.

Coefficients of the meta-analysis.

The Forest Plot (Figure 2) presents the effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals for each study included in the analysis. The analysis indicates significant heterogeneity (I2 = 99.688%), as evidenced by the wide dispersion of effect sizes around the overall estimate. This variability highlights the diversity in study contexts and methodologies, reinforcing the need for careful interpretation of the data.

The Funnel Plot (Figure 3) presents the distribution of effect sizes about their standard errors. The plot demonstrates symmetry, which suggests a low likelihood of publication bias. The clustering of data points around the line representing the overall effect size (0.43, 95% CI: 0.40–0.46) further reinforces the credibility of the meta-analysis results.

Figure 3.

Funnel Plot: assessment of bias.

The certainty of evidence for each key outcome was assessed using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) framework. This approach evaluated evidence based on study design, risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, and imprecision. Each outcome was rated as high, moderate, low, or very low certainty. GRADE assessments were applied to ensure transparency and reliability in synthesizing the evidence for psychological, social, and environmental outcomes.

This meta-analysis demonstrated that outdoor activities exerted a significant positive impact on the psychological and social well-being of children and adolescents. The calculated overall effect size of 0.43 (95% CI: 0.40–0.46; p < 0.001) indicated a moderate yet meaningful contribution of outdoor activities in improving mood, reducing anxiety, and fostering emotional stability. These findings were consistent with the existing literature that highlighted the multidimensional benefits of nature-based engagement.

The presence of significant heterogeneity (Cochran’s Q = 9614.110, df = 21, p ≤ 0.001; Higgins’ I2 = 99.688%) highlighted substantial variability across the included studies, suggesting that variations among results were influenced by methodological and contextual differences. Furthermore, the Tau-squared (τ2) estimate of 0.001 supported the high variability among study outcomes, warranting careful interpretation of the synthesized results. The symmetrical distribution observed in the Funnel Plot indicated minimal publication bias, further enhancing the robustness of the findings. The Forest Plot reinforced these conclusions, depicting consistent effect sizes that were widely dispersed but converged around the overall estimate of 0.43 (95% CI: 0.40–0.46).

A thematic approach was used to categorize the qualitative findings into three primary sections (Table 4):

Table 4.

Complication of the selected studies in the meta-analysis.

Psychological and Health Well-Being: Outdoor activities demonstrated substantial benefits in reducing anxiety, improving mood, and enhancing emotional stability. Mechanisms for these improvements include the calming effects of natural settings and the physiological benefits of physical activity, such as endorphin release. Schneider et al. (2024) reported that outdoor athletic activities helped protect adolescents from climate-related health risks, fostering emotional resilience. Similarly, Veitch et al. (2021) demonstrated how park accessibility and quality positively influenced psychological well-being. Akpınar (2019) highlighted the significant role of green spaces in reducing psychological distress among adolescents, while Mathisen et al. (2023) showed that engaging in outdoor spaces improved emotional stability through increased physical activity. Lawler et al. (2017) emphasized the psychological motivation linked with team sports, particularly among boys. Fromel et al. (2017) noted the positive effects of outdoor activities on both health and emotional well-being. Parker et al. (2016) highlighted how active commuting and outdoor play significantly improved well-being by reducing BMI and waist circumference. Finally, Manferdelli et al. (2019) referred multiple benefits for health and society from outdoor physical activities. Larouche et al. (2019) connect to public health and epidemiology by examining how outdoor time influences childhood obesity, physical activity, and sedentary behavior across diverse socioeconomic and climatic contexts, offering insights into global health trends. Additionally, it explores psychological well-being, emphasizing that outdoor play fosters resilience, self-regulation, and coping skills, which contribute to improved mental health in children.

Social Connectedness: Outdoor activities fostered interpersonal relationships and group dynamics by encouraging teamwork, communication, and leadership skills. Collaborative initiatives, such as community projects and team sports, were particularly effective. Down et al. (2023) described how structured outdoor programs promote self-awareness and social bonding. Similarly, Triana et al. (2019) found that group-based outdoor initiatives, such as open street events, fostered community engagement and stronger social ties. Loebach et al. (2021) highlighted the importance of green spaces in fostering physical activity and social connections, while Rivera et al. (2022) explored the complex relationship between activity type and social interaction. Peréa et al. (2019) emphasized the role of youth leadership and community ownership fostered through park advocacy and assessments.

Environmental Awareness: Engagement with nature promoted sustainable behaviors and a deeper connection to the environment. Outdoor activities combined with urban renewal or environmental education were especially effective in cultivating environmental responsibility. Zafeiroudi and Hatzigeorgiadis (2014) found significant improvements in environmental beliefs among adolescents participating in outdoor pursuits. Similarly, Grigoletto et al. (2022) emphasized how green spaces and outdoor physical activities encouraged sustainable practices. Sefcik et al. (2019) observed that perceptions of green environments promoted responsible behaviors, while Andersen et al. (2017) showed how urban renewal initiatives improved outdoor engagement and environmental stewardship. Poulain et al. (2020) highlighted how green spaces positively impacted activity and environmental use. Finally, Tarun et al. (2017) examined how outdoor school environments influence sustainable behaviors and promote physical activity through better infrastructure and safety features. Zafeiroudi (2020) demonstrated that outdoor activity programs improve teamwork and foster collective environmental responsibility.

The GRADE framework was applied to assess the certainty of evidence for the primary outcomes:

Psychological Benefits: Evidence for improved mood, reduced anxiety, and emotional stability was rated as moderate certainty. This rating reflected consistent findings across studies but is limited by reliance on self-reported measures and variability in study designs.

Social Connectivity: The evidence for strengthened social bonds, enhanced group dynamics, and improved interpersonal relationships was rated as high certainty, supported by consistent results across diverse contexts and robust study designs.

Environmental Awareness: Evidence for fostering environmental responsibility was rated as low certainty due to reliance on indirect measures, variability in assessment tools, and inconsistent findings across studies.

4. Discussion

Engaging in outdoor activities has been shown to significantly enhance psychological well-being, social connectivity, and environmental awareness among children and adolescents. The findings of this systematic review reinforce existing evidence while highlighting fresh insights into the multifaceted benefits of outdoor recreation. This section delved deeper into these dimensions, integrated theoretical frameworks, and discussed broader implications for educators and stakeholders.

The psychological benefits of outdoor activities are profound and multifaceted. Activities such as hiking, cycling, and nature exploration stimulate endorphin release and reduce cortisol levels, resulting in mood enhancement and stress alleviation (Delucchi, 2021; Lou et al., 2023; Sharma & Shyam, 2023). These findings aligned with established theories in environmental psychology, such as the Biophilia Hypothesis, which posits that humans possess an innate affinity for nature that promotes mental restoration (Gaekwad et al., 2022). The reviewed studies consistently reported reductions in anxiety and depression, further supporting the restorative effects of natural environments. Moreover, the role of outdoor activities in fostering resilience in children and adolescents deserves attention, as early engagement with nature may help cultivate coping mechanisms essential for ongoing mental health (Bowen & Neill, 2016).

Outdoor activities also play a crucial role in fostering social connections and enhancing interpersonal skills. Group-based activities, such as team sports, collaborative environmental projects, and adventure challenges, promote communication, teamwork, and leadership (Zafeiroudi, 2014). These benefits are particularly significant during adolescence, a developmental stage marked by a heightened need for peer interaction and identity formation. The reviewed studies highlighted how structured outdoor programs, such as environmental education initiatives, not only strengthened group dynamics but also instilled a sense of collective responsibility. These findings align with Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory, which emphasizes the importance of social interactions within immediate and broader contexts for healthy development (Ryan, 2001).

Outdoor activities are instrumental in cultivating environmental awareness and fostering sustainable behaviors (Prince, 2017; Zafeiroudi, 2020). Experiences such as gardening, wildlife conservation, and nature observation create emotional connections to the environment, leading to sustained attitudinal and behavioral changes (Hughes, 2013; Mawdsley et al., 2009; Wang & Clark, 2017). These findings resonated with frameworks like the Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) theory, which emphasized the role of personal values and beliefs in driving pro-environmental actions (Ghazali et al., 2019). The reviewed studies revealed that integrating outdoor recreation with environmental education amplifies these effects, emphasizing the need for immersive, hands-on experiences in fostering environmental stewardship among youth.

The application of the GRADE framework revealed varying levels of certainty across the evaluated outcomes. The moderate certainty of evidence for psychological benefits highlighted the need for more objective measures, such as physiological biomarkers, to enhance reliability. In contrast, the high certainty for social connectivity highlighted the robustness of group-based interventions in fostering interpersonal relationships. However, the low certainty for environmental awareness pointed to a gap in direct and consistent measurement of pro-environmental behaviors, suggesting opportunities for methodological improvements in future research.

The findings of this study corroborated those of previous systematic reviews, reinforcing the psychological, social, and environmental benefits of outdoor recreation (Eime et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2025; Holland et al., 2018; Noseworthy et al., 2023). However, unlike prior studies that primarily focus on Western populations, this review synthesizes evidence from diverse geographical and cultural contexts, enhancing the generalizability of its conclusions. While previous research has largely emphasized the physical health benefits of outdoor activities, the present study expands on these findings by demonstrating the significant role of outdoor engagement in fostering social connectedness and environmental responsibility. Additionally, this review highlighted key variations in outcomes across cultural and socioeconomic contexts, suggesting that adolescents in urban environments with limited green spaces may face distinct challenges and benefits compared to their rural counterparts. These findings underline the importance of designing interventions that account for contextual differences. Future research should include underrepresented populations, such as children with disabilities or those from marginalized communities, to ensure that outdoor recreation programs are inclusive and applicable across diverse settings.

Customized interventions are essential to ensuring that the benefits of outdoor activities are accessible to underserved communities. Collaborative approaches involving community organizations, schools, and public–private partnerships could address local needs effectively. For example, leveraging schools as hubs for outdoor engagement, deploying mobile recreation units, and offering subsidized access to equipment could make outdoor activities more inclusive. Community-driven programs that integrate activities such as gardening, sports, and environmental education into daily routines have the potential to foster participation and engagement. These interventions not only enhance physical and mental health but also strengthen social cohesion and environmental awareness.

Existing cultural and socioeconomic programs provide valuable models for designing such interventions. Successful initiatives include Bogotá’s Ciclovía, which transforms urban streets into recreational spaces, and Nordic outdoor schools that emphasize year-round, nature-based learning (Remmen & Iversen, 2023; Triana et al., 2019). Other programs, such as Eastern European school initiatives that integrate outdoor education into curricula and long-term nature excursions, have demonstrated success (Becker et al., 2018). Additionally, the Rock Eagle 4-H Center in Georgia provides environmental education programs that use outdoor settings as interactive learning environments, offering experiential learning opportunities for students (Meighan & Fuhrman, 2018). Community gardening initiatives in the U.S. demonstrate how outdoor activities can be adapted to diverse cultural and environmental contexts (Loebach et al., 2021). These studies emphasize the importance of collaboration, inclusivity, and cultural relevance in creating sustainable and impactful outdoor recreation opportunities.

4.1. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

The present study indicated that outdoor activities enhance the psychological, social, and environmental well-being of children and adolescents. However, several limitations must be considered when interpreting these results. While systematic reviews do not generate new primary data, they provide a comprehensive synthesis of existing research, reducing bias and offering a broader perspective on outdoor recreation’s impact. However, insights from educators who implement outdoor programs could add valuable knowledge. Future research should consider incorporating qualitative approaches, such as interviews or focus groups with practitioners, to complement these meta-analytical findings and explore the practical applications of outdoor learning in more depth. Future research should integrate qualitative methods, such as educator interviews or focus groups, to complement these quantitative findings. This approach would bridge the gap between research and practice, providing deeper insights into the application of outdoor education programs.

Many studies relied on participants’ assessments, which could impact the accuracy of the findings. Participants may overestimate or underestimate their experiences and activities, leading to potential bias and affecting the reliability of the results. One limitation of this study is the exclusion of studies that relied solely on self-reported assessments. While self-reported data provide helpful knowledge into personal experiences, they may introduce biases related to perception and recall. By focusing on studies with more objective measures, this review enhanced the reliability of its findings. Future research could complement this approach by integrating mixed-method designs that combine self-reported data with observational or physiological measures to offer a more comprehensive perspective.

The diversity of samples and geographical contexts in the studies restricted the generalizability of the findings. Most research focused on specific population groups or regions, making it challenging to apply the results to broader populations. Furthermore, several studies employed cross-sectional designs, which did not allow for causal inferences. The lack of comparative control groups and longitudinal data limited study’s understanding of the long-term impact of outdoor activities. Existing studies did not adequately address cultural and socioeconomic variations, which may influence the results and their applicability across different social settings.

To overcome these limitations, future research should focus on experimental designs and the collection of objective data, such as biometric indicators, to assess physical activity and well-being. Additionally, exploring the effects of outdoor activities across various cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds is crucial for understanding differences in participation and benefits.

The exclusion of pandemic-era studies, while methodologically justified, may limit the scope of the findings. These studies often reflect unique circumstances, such as restricted outdoor activity and altered behaviors, which could provide valuable insights into outdoor recreation’s role during crises. Studies published between 2020 and 2022 were excluded to minimize the potential confounding effects of COVID-19 restrictions, which significantly altered outdoor recreation behaviors and accessibility (Arundell et al., 2022; Bernat et al., 2022; Ferguson et al., 2023; Hansen et al., 2023). The pandemic led to widespread lockdowns, variations in outdoor policies, and increased remote participation, which could distort findings regarding the long-term benefits of outdoor activities under normal conditions. A comparative analysis of pre- and post-pandemic trends would be valuable for future research to assess how COVID-19 influenced outdoor engagement and its associated benefits.

While this review identified significant heterogeneity among the included, subgroup analyses and meta-regression were not performed to explore potential sources of variability. The absence of these analyses limits the ability to identify specific moderators that may influence the observed outcomes, such as participant demographics, intervention types, or study methodologies. Future research could use these approaches to better understand the factors contributing to variability and refine recommendations for practice. Subgroup analysis could explore differences based on age groups, intervention formats, or geographical contexts, while meta-regression could assess the impact of study-level variables such as intervention duration or outcome measurement tools.

Future research should focus on designing interventions that consider climate impacts, ensuring outdoor activities remain safe and accessible despite these challenges. Furthermore, integrating outdoor activities into educational programs could play a pivotal role in promoting environmental awareness and the physical well-being of children and adolescents. Investigating the development and implementation of such programs across diverse social and educational settings will help maximize their impact and reach.

4.2. Applications and Actionable Recommendations

The findings of this study highlighted significant implications for education and community programs. Incorporating outdoor activities into school curricula enhanced students’ mental health and social skills. Policies encouraging outdoor space use, particularly in urban areas, reduced stress and improved social cohesion. Local schools, authorities, and policymakers were encouraged to promote outdoor programs that foster physical activity and interaction.

Adolescents’ distinct developmental needs made outdoor activities such as team sports, group hikes, and adventure challenges ideal for social bonding. Hands-on environmental education projects, including community gardening and wildlife conservation, deepened their engagement and sense of responsibility. Climate change necessitated adapting outdoor activities for safety and accessibility. Strategies like shaded areas, hydration stations, and seasonal scheduling ensured participation despite rising temperatures and extreme weather. Seasonal activity variations, such as water-based options in summer and nature exploration in cooler months, also improved engagement. Outdoor activities also fostered teamwork and social interaction, encouraging collaboration, leadership, and communication. Group projects, such as cooperative environmental initiatives, enhanced social bonds and emotional well-being.

Policymakers and educators must prioritize outdoor activities to promote youth development and environmental stewardship. Climate-adapted programs featuring shaded areas and seasonal scheduling ensured safety and inclusivity. Investment in accessible green spaces with amenities like hydration stations and pathways catered to diverse populations and abilities. Schools integrated outdoor recreation into curricula through initiatives like “Eco Lifestyle” to teach sustainability interactively. Hands-on projects, such as gardening and wildlife observation, reinforced ecological responsibility and well-being. Gamification further engaged adolescents by transforming outdoor activities into exciting, tech-driven experiences.

Evaluating outdoor programs through participation rates, diversity metrics, and environmental outcomes—such as increased recycling or reduced waste—ensured impact and sustainability. Surveys and focus groups assessed psychological and social benefits, while longitudinal studies provided insights into lasting effects on well-being and behavior. By implementing these strategies, stakeholders and educators could create inclusive, sustainable outdoor programs that positively impacted youth development and resilience. Collaboration and continuous evaluation ensured these initiatives remained effective and adaptable for future generations.

4.3. Integrating Outdoor Activities into School Curricula: A Holistic Approach

Outdoor activities have the potential to significantly enhance educational experiences, aligning with core goals such as promoting physical health, fostering teamwork, and cultivating environmental stewardship. By embedding outdoor activities within school curricula, educators could provide students with opportunities to engage with nature while achieving academic and developmental objectives. Structured outdoor programs could complement traditional classroom learning, creating a well-rounded and dynamic approach to education.

To maximize the impact of such initiatives, professional development opportunities for teachers are essential. Equipping educators with the skills and knowledge to design and lead effective outdoor education programs could ensure the delivery of meaningful and impactful experiences. Teacher training programs should focus on practical strategies, safety protocols, and methods for integrating outdoor lessons into diverse subject areas.

Schools must also focus on inclusivity when developing outdoor learning spaces. Creating environments that accommodate the needs of all students, including those with physical or learning challenges, is vital to ensuring equal access and participation. Thoughtful design, such as wheelchair-accessible paths and sensory-friendly zones, can foster a sense of belonging and inclusion for every student.

Collaboration with local organizations, such as parks, environmental groups, and community leaders, could enhance the effectiveness of outdoor education initiatives. These partnerships provide schools with valuable resources, expertise, and opportunities for students to engage in real-world projects. By working together, schools and communities create a stronger foundation for environmental education and community involvement.

Outdoor education also offers unique opportunities for fostering holistic student development. Activities such as team-based challenges, nature exploration, and cooperative projects teach essential soft skills like resilience, leadership, and problem-solving. These skills are not only crucial for academic success but also prepare students for life beyond the classroom, equipping them to navigate complex social and professional environments.

Moreover, integrating outdoor activities with sustainability practices, such as gardening, wildlife conservation, or recycling projects, could instill pro-environmental values in students. These experiences nurture a lifelong sense of responsibility towards the environment and inspire behaviors that contribute to sustainable living.

Incorporating outdoor activities into school curricula represents a powerful strategy for fostering physical, emotional, and intellectual development. With proper training, inclusive practices, community collaboration, and a focus on sustainability, schools can create transformative educational experiences that benefit students and society as a whole.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review demonstrated evidence of the psychological, social, and environmental benefits of outdoor activities for children and adolescents. Activities such as hiking, cycling, outdoor camp and nature exploration were associated with reduced anxiety and depression, improved mood, strengthened social connections, and enhanced environmental responsibility. These findings emphasized the critical role of outdoor activities in promoting holistic development and well-being during formative years.

However, the review revealed disparities in access and outcomes influenced by socioeconomic, cultural, and geographical contexts. Urban youth with limited access to green spaces faced distinct challenges compared to their rural counterparts, underlining the need for targeted interventions. Furthermore, outdoor activities demonstrated potential in addressing climate adaptation challenges by fostering environmental education and equipping youth with the knowledge and skills needed to develop sustainable lifestyles.

Incorporating outdoor activities into school curricula and community programs may enhance mental health, promote social cohesion, and instill environmental stewardship among youth. Educators and policymakers should create accessible green spaces and design adaptive outdoor programs that consider climate variability, ensuring equitable participation and sustainability. By fostering collaborative efforts between educators, researchers, and policymakers, the benefits of outdoor recreation could be maximized, contributing to the development of healthier, more resilient, and environmentally conscious future generations.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data, code, and materials used in this systematic review are not publicly available. Researchers interested in accessing these materials are encouraged to contact the corresponding author for further information. This systematic review is registered in PROSPERO under the registration number CRD42025636831.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akpınar, A. (2019). Green exercise: How are characteristics of urban green spaces associated with adolescents’ physical activity and health? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(21), 4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, H. B., Christiansen, L. B., Klinker, C. D., Ersbøll, A. K., Troelsen, J., Kerr, J., & Schipperijn, J. (2017). Increases in use and activity due to urban renewal: Effect of a natural experiment. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53(3), e81–e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arundell, L., Salmon, J., Timperio, A., Sahlqvist, S., Uddin, R., Veitch, J., Ridgers, N. D., Brown, H., & Parker, K. (2022). Physical activity and active recreation before and during COVID-19: The our life at home study. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 25(3), 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, P., Humberstone, B., Loynes, C., & Schirp, J. (Eds.). (2018). The changing world of outdoor learning in Europe. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bernat, S., Trykacz, K., & Skibiński, J. (2022). Landscape perception and the importance of recreation areas for students during the pandemic time. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 9837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D. J., & Neill, J. T. (2016). Effects of the PCYC catalyst outdoor adventure intervention program on youths’ life skills, mental health, and delinquent behaviour. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 21(1), 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchecker, M., & Degenhardt, B. (2015). The effects of urban inhabitants’ nearby outdoor recreation on their well-being and their psychological resilience. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 10, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, S. J., Burns, V. E., & Cumming, J. (2015). The role of outdoor adventure education in facilitating groupwork in higher education. Higher Education, 69(4), 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankiw, K. A., Tsiros, M. D., Baldock, K. L., & Kumar, S. (2020). The impacts of unstructured nature play on health in early childhood development: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 15(2), e0229006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delucchi, L. (2021). Hiking and well-being: Does hiking with headphones influence positive affect and attention restoration? Prescott College. [Google Scholar]

- Down, M., Picknoll, D., Piggott, B., Hoyne, G., & Bulsara, C. (2023). “I love being in the outdoors”: A qualitative descriptive study of outdoor adventure education program components for adolescent wellbeing. Journal of Adolescence, 95(6), 1232–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eime, R. M., Young, J. A., Harvey, J. T., Charity, M. J., & Payne, W. R. (2013). A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: Informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M. D., Lynch, M. L., Evensen, D., Ferguson, L. A., Barcelona, R., Giles, G., & Leberman, M. (2023). The nature of the pandemic: Exploring the negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic upon recreation visitor behaviors and experiences in parks and protected areas. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 41, 100498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromel, K., Kudlacek, M., Groffik, D., Svozil, Z., Simunek, A., & Garbaciak, W. (2017). Promoting healthy lifestyle and well-being in adolescents through outdoor physical activity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(5), 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frumkin, H., Bratman, G. N., Breslow, S. J., Cochran, B., Kahn, P. H., Jr., Lawler, J. J., Levin, P. S., Tandon, P. S., Varanasi, U., Wolf, K. L., & Wood, S. A. (2017). Nature contact and human health: A research agenda. Environmental Health Perspectives, 125(7), 75001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaekwad, J. S., Sal Moslehian, A., Roös, P. B., & Walker, A. (2022). A Meta-analysis of emotional evidence for the biophilia hypothesis and implications for biophilic design. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 750245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z., Chee, C. S., Omar Dev, R. D., Liu, Y., Gao, J., Li, R., Li, F., Liu, X., & Wang, T. (2025). Social capital and physical activity: A literature review up to march 2024. Frontiers in Public Health, 13, 1467571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, E. M., Nguyen, B., Mutum, D. S., & Yap, S.-F. (2019). Pro-environmental behaviours and value-belief-Norm theory: Assessing unobserved heterogeneity of two ethnic groups. Sustainability, 11(12), 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoletto, A., Loi, A., Maietta Latessa, P., Marini, S., Rinaldo, N., Gualdi-Russo, E., Zaccagni, L., & Toselli, S. (2022). Physical activity behavior, motivation and active commuting: Relationships with the use of green spaces in Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A. S., Beery, T., Fredman, P., & Wolf-Watz, D. (2023). Outdoor recreation in Sweden during and after the COVID-19 pandemic–management and policy implications. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 66(7), 1472–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbrow, M. (2019). Visitors as advocates: A review of the relationship between participation in outdoor recreation and support for conservation and the environment. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Visitors-as-advocates%3A-a-review-of-the-relationship-Harbrow/ac03548b6cde95624a1e7c476781ba6347281da1 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Holland, W. H., Powell, R. B., Thomsen, J. M., & Monz, C. A. (2018). A systematic review of the psychological, social, and educational outcomes associated with participation in wildland recreational activities. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership, 10(3), 197–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K. (2013). Measuring the impact of viewing wildlife: Do positive intentions equate to long-term changes in conservation behaviour? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(1), 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiviranta, L., Lindfors, E., Rönkkö, M.-L., & Luukka, E. (2024). Outdoor learning in early childhood education: Exploring benefits and challenges. Educational Research, 66(1), 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larouche, R., Mire, E. F., Belanger, K., Barreira, T. V., Chaput, J. P., Fogelholm, M., Hu, G., Lambert, E. V., Maher, C., Maia, J., & Olds, T. (2019). Relationships between outdoor time, physical activity, sedentary time, and body mass index in children: A 12-country study. Pediatric Exercise Science, 31(1), 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, M., Heary, C., & Nixon, E. (2017). Variations in adolescents’ motivational characteristics across gender and physical activity patterns: A latent class analysis approach. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R. L. T., Lane, S., Brown, G., Leung, C., Kwok, S. W. H., & Chan, S. W. C. (2020). Systematic review of the impact of unstructured play interventions to improve young children’s physical, social, and emotional wellbeing. Nursing & Health Sciences, 22(2), 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebach, J., Sanches, M., Jaffe, J., & Elton-Marshall, T. (2021). Paving the way for outdoor play: Examining socio-environmental barriers to community-based outdoor play. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, H., Liu, X., & Liu, P. (2023). Mechanism and implications of pro-nature physical activity in antagonizing psychological stress: The key role of microbial-gut-brain axis. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1143827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manferdelli, G., La Torre, A., & Codella, R. (2019). Outdoor physical activity bears multiple benefits to health and society. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 59(5), 868–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathisen, F. K. S., Torsheim, T., Falco, C., & Wold, B. (2023). Leisure-time physical activity trajectories from adolescence to adulthood in relation to several activity domains: A 27-year longitudinal study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 20(1), 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawdsley, J. R., O’malley, R., & Ojima, D. S. (2009). A review of climate-change adaptation strategies for wildlife management and biodiversity conservation. Conservation Biology, 23(5), 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeks, C. B., & Mauldin, T. (1990). Children’s time in structured and unstructured leisure activities. Lifestyles, 11, 257–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meighan, L. G., & Fuhrman, N. E. (2018). Defining effective teaching in environmental education: A Georgia 4-H case study. Journal of Research in Technical Careers, 2(2), 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noseworthy, M., Peddie, L., Buckler, E. J., Park, F., Pham, M., Pratt, S., Singh, A., Puterman, E., & Liu-Ambrose, T. (2023). The effects of outdoor versus indoor exercise on psychological health, physical health, and physical activity behaviour: A systematic review of longitudinal trials. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, N., Atrooshi, D., Lévesque, L., Jauregui, E., Barquera, S., Taylor, J. L. y., & Lee, R. E. (2016). Physical activity and anthropometric characteristics among urban youth in Mexico: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 13(10), 1063–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peréa, F. C., Sayles, N. R., Reich, A. J., Koomas, A., McMann, H., & Sprague Martinez, L. S. (2019). “Mejorando nuestras oportunidades”: Engaging urban youth in environmental health assessment and advocacy to improve health and outdoor play spaces. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(4), 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulain, T., Sobek, C., Ludwig, J., Igel, U., Grande, G., Ott, V., Kiess, W., Körner, A., & Vogel, M. (2020). Associations of green spaces and streets in the living environment with outdoor activity, media use, overweight/obesity and emotional wellbeing in children and adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, H. E. (2017). Outdoor experiences and sustainability. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 17(2), 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhakka, R. (2021). University students’ participation in outdoor recreation and the perceived well-being effects of nature. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 36, 100425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remmen, K. B., & Iversen, E. (2023). A scoping review of research on school-based outdoor education in the Nordic countries. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 23(4), 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, E., Veitch, J., Loh, V. H., Salmon, J., Cerin, E., Mavoa, S., Villanuella, K., & Timperio, A. (2022). Outdoor public recreation spaces and social connectedness among adolescents. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, C. J., & Janse Van Rensburg, N. (2019). The effect of an outdoor adventure programme with selected team-building and cultural activities on the personal effectiveness of students. African Journal for Physical Activity and Health Sciences (AJPHES), 25(1), 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, D. P. (2001). Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory. Retrieved October, 7, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, S., Niederberger, M., Kurowski, L., & Bade, L. (2024). How can outdoor sports protect themselves against climate change-related health risks?—A prevention model based on an expert delphi study. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 27(1), 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefcik, J. S., Kondo, M. C., Klusaritz, H., Sarantschin, E., Solomon, S., Roepke, A., South, E. C., & Jacoby, S. F. (2019). Perceptions of nature and access to green space in four urban neighborhoods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(13), 2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A., & Shyam, V. (2023). From stress buster to mood elevator: Role of mother nature in well-being. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(4), 474–478. [Google Scholar]

- Tarun, S., Arora, M., Rawal, T., & Benjamin Neelon, S. E. (2017). An evaluation of outdoor school environments to promote physical activity in Delhi, India. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Triana, C. A., Sarmiento, O. L., Bravo-Balado, A., González, S. A., Bolívar, M. A., Lemoine, P., Meisel, J. D., Grijalba, C., & Katzmarzyk, P. T. (2019). Active streets for children: The case of the Bogotá Ciclovía. PLoS ONE, 14(5), e0207791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J., Rodwell, L., Abbott, G., Carver, A., Flowers, E., & Crawford, D. (2021). Are park availability and satisfaction with neighbourhood parks associated with physical activity and time spent outdoors? BMC Public Health, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Z., & Clark, P. B. (2017). The environmental impacts of home and community gardening. CABI Reviews, 2016, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafeiroudi, A. (2014). Physical education & environmental education: The influence of an outdoor activities program on environmental responsibility. Inquiries in Sport & Physical Education, 11(3), 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Zafeiroudi, A. (2020). Enhancing adolescents’ environmental responsibility through outdoor recreation activities. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 9(6), 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafeiroudi, A. (2021). Exploring outdoor play in kindergartens: A literature review of practice in modern Greece. Journal of Studies in Education, 11(3), 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafeiroudi, A., & Hatzigeorgiadis, A. (2014). The effects of an outdoor pursuit’s intervention program on adolescents’ environmental beliefs. International Journal on Advances in Education Research, 1(3), 106–118. [Google Scholar]

- Zafeiroudi, A., & Kouthouris, C. (2021). Teaching outdoor adventure activities in preschools: A review of creativity and learning development. International Journal of Learning and Development, 11(2), 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwart, R., & Ewert, A. (2022). Human health and outdoor adventure recreation: Perceived health outcomes. Forests, 13(6), 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).