Abstract

Both the profession and education of graphic design have embraced the sustainability trend. However, in emerging contexts like Mexico, the focus on environmental issues often overshadows the social dimension of sustainability. This study, unique in its focus, examines, from the students’ perception, the influence of social sustainability (SS) practices in design professionals on the SS orientation of graphic design students. Using a Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Model (SEM-PLS) for non-parametric statistical analysis, data from n 136 university students were collected. The results reveal a positive influence of SS professional practices on student orientation toward general sustainability and SS. Notably, this study identified a significant indirect relationship, underscoring the importance of integrating a socially sustainable perspective into academic training. This finding supports the notion that students, when exposed to socially responsible practices in their professional environment, cultivate a culture of sustainability that encompasses the social and community aspects of the discipline.

1. Introduction

Sustainability has evolved as a fundamental approach for the integral development of societies and organizations, integrating economic, environmental, and social dimensions (Hutchins & Sutherland, 2008). However, the social dimension of sustainability needs to be addressed more than the economic and environmental aspects, even though it is essential for community well-being and the development of equitable and just relationships (Gladwin et al., 1995). This situation is especially evident in fields of education such as graphic design, where sustainable practices and values have tended to focus on the environmental impact of design, mainly neglecting the social implications of this discipline (Lee, 2021). Graphic design education has shown efforts to include sustainable approaches but with a bias toward the ecological. At the same time, social sustainability—vital for an inclusive and community-oriented practice—remains a peripheral dimension (Corsini & Moultrie, 2021).

Social aspects within graphic design are not new; some studies have already addressed social empowerment and inclusion from approaches other than sustainability, prioritizing art as a tool for urban regeneration and community cohesion. For example, Gamba (2023) analyzed projects such as Tracce Urbane and Pigmenti in the suburbs of Bergamo, where graphic design and murals transformed public space by addressing inequality, historical memory, and marginalization. These projects engaged international artists and vulnerable groups, such as immigrants and people with disabilities, promoting shared narratives and a sense of belonging. Unlike social sustainability, which integrates equity and rights from a structural perspective, this approach is based on direct action and the co-construction of the urban landscape through community participation.

In this sense, one of the main challenges to the evolution of graphic design teaching toward a socially sustainable approach lies in educational programs’ institutional and disciplinary inertia. Many curricula still prioritize technical and creative training without sufficiently linking this knowledge to social and ethical issues (Findeli, 2001). In addition, the structure of design teaching in various institutions lacks interdisciplinary integration mechanisms, which limits the development of critical competencies in students. Collaboration with other disciplines, such as sociology, economics, and anthropology, could be key to broadening the understanding of graphic design as part of a broader social and economic system. However, implementing these changes requires a transformation in teacher training and how learning is assessed in design, promoting more reflective and participatory methodologies (Arno et al., 2022).

In Nguyen and Mougenot (2022), it is argued that integrating collaborative methodologies into design amplifies its impact and transforms how its teaching is conceived. Through the analysis of multidisciplinary teams, they identified that the participation of designers in interdisciplinary processes fosters a more holistic understanding of the social and economic context in which they operate. In this sense, incorporating diverse perspectives in the teaching of graphic design allows students to acquire critical tools to address social problems from a more comprehensive vision. However, they also warn that the fragmentation of knowledge and methodological differences between disciplines can represent challenges in implementing this approach, underscoring the need to develop pedagogical strategies that promote effective collaboration and systems thinking in the training of designers.

Although design education has begun to integrate sustainability into its programs in emerging contexts such as Mexico, a limited understanding of social sustainability prevails. This reinforces the need for a holistic vision in the teaching of graphic design, in which competencies are promoted that allow students not only to create products with a lower environmental impact, but also to design with a focus on social welfare and justice (Ceylan & Soygeniş, 2019; Hong et al., 2020). Social sustainability implies recognizing and responding to fundamental needs for social justice, equity, and community cohesion; this becomes relevant in a profession as influential as graphic design, which has the potential to shape cultural perceptions and consumption patterns (Kazamia & Kafaridou, 2019). However, one of the critical areas of opportunity lies in the limited incorporation of practices and theories that directly address the social impact in graphic design education, both in educational projects and in the professional interaction that students can observe and emulate (Keynoush & Daneshyar, 2022).

The challenges to integrating social sustainability in the teaching of graphic design range from the need for conceptual clarity to the scarcity of practical and structured methodologies that allow its effective implementation in educational programs. Although there are theoretical frameworks such as social capital, stakeholder theory, and corporate social responsibility (CSR) that have been applied in social sustainability studies, these approaches often privilege corporate goals over integral social welfare, which limits their usefulness in educational contexts that require a more student-centered perspective (Foladori, 2005; Hutchins & Sutherland, 2008). In addition, as (Liu et al., 2017) pointed out, the lack of a global consensus on what constitutes social sustainability makes it difficult to establish uniform pedagogical indicators and strategies that can be applied in the training of graphic design students. However, various studies have highlighted that graphic design education must evolve toward an approach that fosters technical and creative skills and addresses complex social problems through design (Zarghami et al., 2017).

The objective of this study is, from the students’ perception, to analyze the relationship between sustainable practices in the professional field of graphic design and the formation of a culture of social sustainability among students of this discipline. Through a Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Model (SEM-PLS), we aimed to determine if there is a direct relationship between the practices observed in the professional environment and the perception and culture of social sustainability developed by students. The empirical statistical methodology used, based on a structured survey applied to 136 university students, provides a basis for examining the influence of these practices on the construction of sustainable values in future graphic designers. The potential impact of our findings on the future of graphic design education is significant, as it could pave the way for a more holistic and socially conscious approach.

The contribution of this article focuses on four central aspects: (i) an innovative perspective by prioritizing the social dimension of sustainability in graphic design, which, in other studies, tends to focus on environmental issues; (ii) unlike traditional studies in the sector, which are often based on simple qualitative or correlational approaches, this work uses a second-generation statistical analysis, SEM-PLS, to analyze the direct and indirect effects of SS practices in professionals on student guidance; (iii) it also uses a theoretical and conceptual approach that has not been previously used in this field, which allows for a deeper understanding of how these values influence students’ commitment to integral sustainability; and (iv) by being carried out in the emerging context of Mexico, it also addresses a gap in the literature, thereby enriching the applicability of its findings to regions where SS in design is still in development.

This manuscript is organized into sections that develop upon key issues to address the proposed objective. First, a literature review will address the social dimension of sustainability and its relevance in design teaching, analyzing the relevant theoretical approaches and backgrounds. In the third section, the theoretical framework and hypotheses based on the institutional theory, the capabilities approach, and the orientation approach in social sustainability, which underlies the empirical research, will be presented. Subsequently, the methodology section will explain the details of the research design, participants, measures, and statistical analysis. The results will be presented in the fifth section, followed by a discussion that will contrast the findings with the existing literature. Finally, the conclusions and educational implications will offer recommendations to strengthen the teaching of social sustainability in graphic design, and this will be followed by a reflection on the limitations and possible lines of future research.

2. The Social Dimension of Sustainability: Concepts, Indicators, and Approaches

2.1. Community Development Approach

The community development approach to social sustainability focuses on strengthening social cohesion and equity in specific communities, aiming to preserve their structure and promote their members’ integral well-being. This approach has been widely implemented in rural areas, where social sustainability is critical for maintaining demographic and socioeconomic functions in vulnerable communities (Jones & Tonts, 1995). The evaluation of SS in these contexts usually includes indicators such as equity in access to resources, quality of life, citizen participation, and the capacity for self-organization (McKenzie & Hawke Research Institute, University of South Australia, 2004). In studies conducted in Australia, for example, these indicators have been applied to assess the impacts of agriculture on the social cohesion and sustainability of farming communities. This approach highlights the importance of social justice, equitable distribution of resources, preservation of cultural identity, and strengthening community interaction. In this context, SS is understood as a necessary condition for sustainable development as it allows communities to subsist and thrive in a resilient and sustainable manner (Dempsey et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2017).

2.2. Corporate Development Approach

The corporate focus on social sustainability addresses the responsibility of organizations to promote fair working conditions and contribute to the well-being of the communities linked to their operations. This approach, supported by theories of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and stakeholders, considers that companies must go beyond profit maximization to include practices that favor social development (Hutchins & Sutherland, 2008). The corporate approach encompasses various dimensions, from workplace equity and occupational health to philanthropy and investment in community programs. For example, CSR studies in the manufacturing and supply sectors have highlighted the importance of occupational justice and safety indicators for creating an organizational culture that promotes social well-being (Mani et al., 2016). In this sense, SS in the corporate sphere involves building relationships of trust and collaboration between the company and the community, ensuring that business practices not only respect, but also benefit the society in which they operate (Corsini & Moultrie, 2021; Lee, 2021).

2.3. Human Development Approach

The human development approach to social sustainability emphasizes the satisfaction of fundamental needs and individual flourishing, which are understood as essential components of social well-being. This approach, common in developed regions, considers social sustainability to promote equitable access to fundamental rights such as health, education, cultural participation, and emotional well-being. Some studies, such as those by Rogers et al. (2012), have proposed models that measure SS regarding access to resources and conditions that allow for a dignified and healthy life, focusing on social inclusion and equal opportunities. At the educational level, this approach has been applied to promote design competencies in students, allowing them to incorporate social justice and human rights values in their work (Kazamia & Kafaridou, 2019). In this way, SS based on human development involves designing policies and programs that facilitate access to essential goods and services, ensuring an environment that promotes the integral development of people and a culture of respect and social support (Pakravan et al., 2022).

2.4. Design, Architecture, and Urbanism-Based Approach

The focus on design, architecture, and urbanism explores how these disciplines contribute to social well-being through practices that foster inclusion, accessibility, and a sense of community. In graphic design, social sustainability is manifested through visual projects that promote values such as cultural diversity and social commitment (Ceylan & Soygeniş, 2019). Architecture and urban planning, on the other hand, address SS through the design of spaces that promote social cohesion, safety, and citizen participation, as in the case of projects that integrate urban agriculture to improve the quality of life in urban contexts (Keynoush & Daneshyar, 2022). Key indicators in this approach include accessibility, the physical attractiveness of spaces, equity in the distribution of services, and the ability of built environments to facilitate social interaction. On the other hand, the urban approach examines SS in contexts of urbanization, where the design of cities and spatial distribution impact the social well-being and cohesion of inhabitants. This approach considers equity in access to housing, infrastructure, and the quality of public spaces, influencing the cohesion and quality of urban life (Colantonio & Dixon, 2011; Hong et al., 2020). The studies by (Dempsey et al., 2011) highlight the importance of urban environments fostering social participation and a sense of belonging, establishing SS as a tool for evaluating the effectiveness of inclusive urbanization policies. Thus, this multidimensional approach underscores that both graphic and architectural design and urban planning play a fundamental role in the construction of a culture of social sustainability, where well-being and community empowerment are promoted through inclusive and accessible visual and spatial practices (Corsini & Moultrie, 2021; Hong et al., 2020).

3. Social Sustainability in Design Education

The educational role of social sustainability in graphic design focuses on how this discipline can contribute to social cohesion and well-being through projects that promote inclusion and social justice. In graphic design, social sustainability is integrated through visual messages that promote social awareness and respect for cultural diversity in architecture and public space design projects that are increasingly oriented toward accessibility, safety, and community participation (Ceylan & Soygeniş, 2019; Corsini & Moultrie, 2021). This approach suggests that graphic designers and architects are responsible for building a culture of social sustainability into their practices, addressing issues such as emotional well-being, sense of belonging, and social interaction in the design of physical and visual environments. Educational and professional experiences in this field foster a holistic vision that incorporates indicators of social sustainability, such as equitable access to resources, the development of inclusive spaces, and the strengthening of cultural identity, which are all essential aspects for training professionals who actively contribute to sustainable social development (Kazamia & Kafaridou, 2019; Keynoush & Daneshyar, 2022).

Therefore, sustainability in the education of graphic design and architecture students has gained importance in recent years due to this discipline’s significant impact on the environment and society. As a visual communication tool, graphic design can influence social behaviors and perceptions, making training in this area crucial to promoting a culture of social sustainability among future professionals (Zarghami et al., 2017). However, in many educational programs, a bias toward the environmental approach persists, while elements of social sustainability remain peripheral (Ceylan & Soygeniş, 2019; Hong et al., 2020). This imbalance in design education limits students’ ability to integrate values of social justice, equity, and community well-being into their projects and practices, which are essential for a complete understanding of sustainability (Pakravan et al., 2022).

The interest in integrating the social dimension in teaching design has resulted in various educational proposals that seek to promote social responsibility in students. Social sustainability is defined as the ability to meet current needs without compromising the opportunities of future generations, focusing on social justice, equity, and quality of life (Corsini & Moultrie, 2021). This approach highlights the importance of teaching students to recognize the value of social relationships, cultural diversity, and citizen participation in building sustainable communities. An example of this type of approach is the “Graduate Design Studio” pedagogy, which was implemented in Turkey, where urban agriculture was integrated into architectural design to improve urban quality of life and psychological well-being, promoting a sense of belonging and community interaction in graduate students (Keynoush & Daneshyar, 2022; Pakravan et al., 2022). Likewise, design projects must include participatory and collaborative dimensions that, according to (Corsini & Moultrie, 2021), foster social resilience and strengthen the commitment of future designers to the well-being of their communities.

Regarding the indicators of social sustainability applied in design education, an approach that integrates multiple dimensions, such as physical and emotional health, accessibility, gender equity, and the sense of safety in public spaces, has been proposed (Ceylan & Soygeniş, 2019). These indicators reflect the need for students to acquire technical skills and develop competencies to evaluate and promote social welfare through their projects. Recent studies have underscored the importance of “question pedagogy” as an educational strategy to foster a critical mindset in students, motivating them to question how their designs can contribute to solving pressing social problems and promoting inclusive and equitable values (Kazamia & Kafaridou, 2019). This comprehensive perspective in designer education aligns with the growing recognition of social sustainability as essential for responsible and transformative professional practice in graphic design.

4. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Support

4.1. Theory and Conceptual Framework

Institutional Theory, which was formulated by (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983), proposes that actors within an institutional field tend to imitate the norms and practices established by other organizations due to isomorphic pressures of a coercive, mimetic, or normative type. This process of mimicry is especially relevant in the educational context, where graphic design students, as stakeholders of their academic institutions, can adopt social sustainability practices by observing their implementation in the professional field (Jennings & Hoffman, 2021). This theory is applicable in the education of future graphic designers, who, influenced by the culture of sustainability of professionals in the sector, tend to incorporate these values into their practices, reinforcing an orientation toward social justice and equity in their work (Colantonio & Dixon, 2011; Dempsey et al., 2011).

On the other hand, Amartya Sen’s (Sen, 1993) Theory of Capabilities states that people’s sustained well-being depends on their ability to generate and maintain conditions conducive to their development. In this sense, Sen stresses that aspects such as education, gender equality, decent work, and health are essential elements for long-term social empowerment. Applied to the context of social sustainability in graphic design, this theory suggests that educational programs should promote not only technical competencies, but also capacities to respond to social challenges of equity and well-being, enabling students to contribute meaningfully to sustainable development (Kazamia & Kafaridou, 2019; Pakravan et al., 2022). This approach is reinforced in urban and architectural design, where SS is understood as a critical dimension that fosters accessibility, inclusion, and collective well-being (Ceylan & Soygeniş, 2019; Keynoush & Daneshyar, 2022).

This work is based on the premise that the teaching of graphic design has a collaborative and multidisciplinary nature that goes beyond its technical and commercial training, aligning itself with empirical approaches that have evidenced the limitations of its social impact. While some studies highlight its potential in urban regeneration and inclusion (Gamba, 2023), the poor integration of social dimensions in educational programs restricts the development of critical competencies in students (Findeli, 2001). Collaboration with disciplines such as sociology and economics could broaden this perspective; however, methodological differences and fragmentation of knowledge continue to represent barriers to its implementation (Nguyen & Mougenot, 2022). Rethinking design pedagogy requires questioning the role of the designer and his or her social responsibility, promoting interdisciplinary approaches that foster a more critical and systemic vision of the profession.

Some important distinctions were made from the conceptual framework proposed by (Marshall et al., 2015). On the one hand, there is the distinction between sustainability and social sustainability. Sustainability frames the joint vision of the triple bottom line (environmental, social, and economic); on the other hand, social sustainability is related to human and community well-being. Likewise, (Marshall et al., 2015) identified three levels of sustainability mainstreaming (guidance, basic practices, and advanced practices). These concepts are relevant to this study since two levels of the conceptual framework were applied to measure our variables: “Orientation” and “Practices”. “Orientation" implies an awareness of the importance, although it does not necessarily imply practice. The concept of “Practices” entails a progression in the adoption of actions, which, in this case, is related to sustainability.

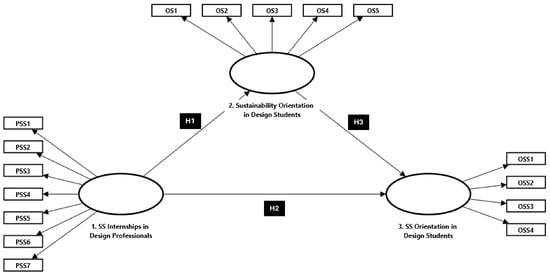

Based on the conceptual framework indicated, when we talk about the latent variable “1. Sustainability Practices in Design Professionals”, it refers to the student’s perception of the social sustainability practices they observe in the practice of design professionals (such as, for example, their teachers). Our variable, “2. Orientation on sustainability in design students” explores the self-perception that university students have about their awareness of the importance of sustainability (triple result). Finally, our variable, “3. Orientation toward social sustainability in design students” explores the self-perception that university students have about their awareness of the importance of sustainability on social issues. The proposed theories and conceptual approaches offer a solid basis for understanding how design students can develop an orientation toward SS and evolve toward more profound practices that positively impact society.

4.2. SS Practices and Sustainability Orientation

By observing the sustainable practices implemented in the professional sector, students develop an orientation toward sustainability, which refers to the cognitive acceptance of the importance of these practices for sustainable development (Marshall et al., 2015). In the design field, practices that integrate values of equity and social justice promote an ethical orientation in professionals and model a culture of sustainability that students tend to imitate (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Jennings & Hoffman, 2021). In addition, various studies indicate that students exposed to sustainability practices in graphic design assimilate values of social responsibility and justice, thus recognizing the interdependence of the social, environmental, and economic aspects in design (Ceylan & Soygeniş, 2019; Kazamia & Kafaridou, 2019). This initial orientation process aligns with the theoretical approach of (Marshall et al., 2015), who argue that orientation toward sustainability is a predictor that can facilitate the implementation of more advanced practices. Institutional Theory, as well as the approach based on community development in SS, suggests that the academic and professional environment promotes a cultural integration of these values, consolidating the orientation to sustainability in students (Dempsey et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2017). Therefore, the first hypothesis of this work can be deduced:

H1.

A positive relationship exists between Social Sustainability Practices in design professionals and Sustainability Orientation in design students.

4.3. SS Practices and SS Orientation

Amartya’s (Sen, 1993) theory of capabilities reinforces the idea that, to foster sustainable student engagement, an environment where education in social justice, gender equity, and labor rights is actively promoted is essential. Studies have highlighted how indicators of SS in design, such as inclusion and gender equity, shape students’ perception of the importance of these values in their future professional practices (Corsini & Moultrie, 2021; Lee, 2021).

Likewise, the observation of sustainable professional practices impacts the development of a specific orientation toward social sustainability, where dimensions such as community well-being, social cohesion, and inclusion are valued, and critical issues in the education of graphic designers who seek to apply their work to real and complex contexts (Kazamia & Kafaridou, 2019; Keynoush & Daneshyar, 2022). Marshall et al. (2015) support this approach by establishing that the orientation toward social sustainability is a crucial facilitator for implementing socially sustainable practices, which is evidenced by students’ interest in promoting social justice in their projects. This commitment is also observed in urban and community design environments, where sustainability is directly related to the design of accessible and equitable spaces (Colantonio & Dixon, 2011; Dempsey et al., 2011). Therefore, the second hypothesis of this work can be deduced:

H2.

There is a positive relationship between the Social Sustainability Practices of design professionals and the Orientation to Sustainability in design students.

4.4. Sustainability Orientation and SS Orientation

According to (Marshall et al., 2015), the orientation toward general sustainability can serve as a basis for developing a more specific orientation toward social sustainability, allowing students to integrate values of justice and equity into their practices. Studies that underscore the importance of an initial orientation toward sustainability to foster deeper commitments in terms of SS (Missimer et al., 2017; Vallance et al., 2011) support this progressive relationship.

The human development approach to SS is also relevant here as it highlights how the sustainability orientation can evolve to include values of human rights and integral well-being, primarily when it is based on foundations of social justice (Hong et al., 2020; Pakravan et al., 2022). Therefore, this initial orientation catalyzes graphic design students to assume an ongoing commitment to SS and translate it into their future professional practices. By promoting an orientation toward sustainability, the educational and professional context makes it easier for students to delve into inclusion and equity, which are critical topics in graphic design education and are necessary to address current sustainability challenges (Corsini & Moultrie, 2021; Opp, 2017). Therefore, the third hypothesis of this work can be deduced:

H3.

There is a positive relationship between Sustainability Orientation and Social Sustainability Orientation in the design student.

Figure 1 graphically represents the hypothesis relationship model.

Figure 1.

A relationship model of the hypothesis.

5. Methodology

The present research adopted an empirical, statistical, and cross-sectional approach. According to (Wacker, 1998), this methodology allows, through large samples, to establish specific generalizations about the relationship between variables, which is essential for theorizing about the phenomenon studied in the current context. The findings obtained from these generalizations contribute to verifying the relationships that have been suggested in theoretical models that were previously explored by posterior methods in detailed case studies.

5.1. Participants

Data were collected through an electronic survey distributed through WhatsApp and applied to graphic design students and related disciplines, with the support of their contact networks and professors. The snowball and convenient sampling methods allowed for a sufficient and adequate sample, although not strictly representative, to explore the orientation toward social sustainability in design students (Sekeran2013p, 2013). The survey used a 5-point Likert scale (0 = do not at all agree; 4 = strongly agree) to measure the students’ perception of social sustainability in their education. An essential condition for participating in this survey was that they were university students in a design-related career. Table 1 presents a breakdown of the characteristics of the sample (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample (n = 136).

As can be seen, in total, the sample was composed of 136 participants selected from different universities, with a predominant presence of students from the Autonomous University of Tamaulipas, the Faculty of Higher Studies Acatlán (UNAM), and the Institute of Higher Studies of Tamaulipas (IEST Anáhuac)—who made up the highest frequencies in the university profile. Regarding geographical distribution, the participants were primarily concentrated in Tampico, Mexico City, and Reynosa. Most respondents, mainly first- and second-year students, were in the initial stage of their bachelor’s degree studies in graphic design.

5.2. Measures

The measures for this study were developed from an exhaustive review of the literature on social sustainability in design based on preexisting theoretical and conceptual frameworks such as Marshall et al.’s model (Marshall et al., 2015) and Amartya Sen’s Theory of Capabilities (Sen, 1993). Following these approaches, the instrument was designed to capture three main dimensions of social sustainability in the educational context of graphic design: SS Practices in Design Professionals (PSS), Sustainability Orientation in Design Students, and SS Orientation in Design Students.

5.2.1. Section SS Internships in Design Professionals (PSS)

This dimension assesses student perception of the frequency and relevance of social issues in the professional design projects in their region. Based on the perspective of (Sen, 1993) and the degrees of involvement with social sustainability proposed by (Marshall et al., 2015), this construct reflects critical aspects of social performance. The items that make up this dimension include issues such as health, emotional well-being, social security, human rights, gender equity, inclusion, and social cohesion, all of which are considered essential components of social sustainability in design (Kazamia & Kafaridou, 2019; Vallance et al., 2011). Health and safety issues are assessed in the design context for their impact on quality of life (Ceylan & Soygeniş, 2019), while equity and human rights reflect a fundamental concern for social justice in design practice (Sen, 1993).

5.2.2. Orientation to Sustainability in Design Students

This dimension measures student attitudes toward sustainability, focusing on developing knowledge and integrating sustainable practices into their work. The items cover both environmental and social aspects, allowing us to evaluate the degree of understanding of sustainability concepts and their application in design projects. This approach is based on the stages of sustainability incorporation proposed by Marshall et al., where developing an orientation toward sustainability is considered crucial in forming professional competencies (Corsini & Moultrie, 2021; Opp, 2017).

5.2.3. Orientation to SS in Design Students

This last dimension examines the specific knowledge that students possess about social sustainability. The items include the differentiation between environmental and social sustainability, access to sufficient information, and the ability to explain social sustainability in the design field based on social justice and well-being (Marshall et al., 2015; Vallance et al., 2011). This dimension seeks to analyze how students integrate the social approach to sustainability in their training and professional practice. The final instrument consists of 3 dimensions and 17 items, and it is found in its full version in Table A1. The items were reviewed to ensure their adequacy to the Latin American educational and cultural context. They followed expert recommendations to avoid ambiguities and ensure conceptual and terminological clarity in each dimension.

5.3. Statistical Analysis

For this research, the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) technique based on Partial Least Squares (PLS) was used and implemented with SmartPLS 4 software (Ringle et al., 2024). The choice of PLS-SEM allows us to analyze little-explored contexts and examine multiple causal relationships between latent variables. According to (Hair et al., 2019b), PLS-SEM is suitable for exploratory research to predict constructs and extend theories to new contexts. This technique is instrumental in studies involving complex constructs, such as analyzing social sustainability practices and their influence on student orientation toward these topics (Kazamia & Kafaridou, 2019). The philosophy of PLS-SEM focuses on maximizing the explained variance of the final constructs and evaluating their predictive capacity against the variables that affect them (Marshall et al., 2015). The model was evaluated in three stages: (1) Analysis of the reliability of the indicators and convergent and discriminant validity. (2) Measurement of the structural model with path coefficients and explanatory power. (3) Evaluation of the out-of-sample predictive power by bootstrapping, following the recommendations of (Chin, 1998) in using 10,000 resamplings. This validation process provided a robust basis for interpreting the proposed relationships and their relevance to social sustainability in design education.

6. Results

6.1. Validation of the Measurement Model

To assess the individual validity of the items, SmartPLS 4 (Ringle et al., 2024) and the recommended external load threshold (λ ≥ 0.70) from (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988; Hair et al., 2019b) were used. In this study, the loads ranged from 0.457 to 0.945; some items, especially in “SS Practices in Design Professionals (PSS)”, did not reach the ideal value. However, in social sciences, retaining items below the threshold is acceptable as long as they do not affect the composite or discriminant validity of the model (Hair et al., 2019b, 2021, 2019a), thereby allowing conceptually relevant items to be retained without compromising reliability. The dimensions of “Orientation to Sustainability” and “Orientation to SS in Design Students” presented satisfactory loads (0.718–0.945), showing adequate reliability in the measurement model (Table 2).

Table 2.

Individual item reliability and convergent construct validity.

Table 2 also contains the results of the evaluation of the consistency and convergent validity of each construct in the measurement model using the metrics of composite reliability (), composite reliability (), and average extracted variance (), which were chosen according to the recommendations of (Hair et al., 2019b). The values ranged from 0.843 to 0.938, and meeting the threshold of ≥0.708 ensures adequate internal consistency for the constructs. The RR presented values between 0.875 and 0.950, exceeding the threshold of 0.70, thus confirming the scales’ internal consistency (Hair et al., 2021). Regarding convergent validity, the AVE values were between 0.505 and 0.826; however, the construct “SS Practices in Design Professionals (PSS)” presented an AVE of 0.505, which exceeded the threshold of 0.50, thus allowing its inclusion in the model.

The discriminant validity of the latent variables was evaluated using the heterotrait–monotrait criterion () of correlations, which allows for verifying that the constructs are empirically different from each other. This criterion, recommended for reflective models, is based on the average correlations between indicators of different constructs, and it was compared to the correlations within the same construct, thus ensuring that each construct was unique and distinct (Hair et al., 2019b; Henseler et al., 2015). This study met the thresholds, guaranteeing discriminant validity in the structural model (Table 3).

Table 3.

The heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio of the correlations’ criterion.

After validating the individual reliability of the reflective items, the internal consistency of the constructs, and the convergent and discriminant validity, the measurement model was concluded to be reliable. This allowed us to proceed with the evaluation of the structural model, test the hypotheses raised, and analyze the causal relationships between the constructs.

6.2. Results of the SmartPLS Structural Model

The analysis of the structural model was carried out using SmartPLS 4 (Ringle et al., 2024), and, firstly, it was verified that there were no collinearity problems with variance inflation factors () below 3.3, which means it was in compliance with the criterion of (Hair et al., 2019b). Next, the significance and relevance of the path coefficients () were evaluated to validate the strength of the relationships within the structural model. The standardized values of the path coefficients varied between −1 and +1, with those close to +1 representing stronger and more positive relationships, which was consistent with the accepted hypotheses of the present study.

To evaluate the predictive power of the model, the values of the dependent variables were analyzed: “Sustainability Orientation in Design Students” ( = 0.26) and “SS Orientation in Design Students” ( = 0.28). These values indicate a moderate level of predictive power within the context of social sciences, where values of 0.750, 0.500, and 0.250 were interpreted as substantial, moderate, and weak, respectively (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988; Falk & Miller, 1992). Additionally, the size of the effect was evaluated, with values of 0.35 for the relationship between “SS Practices in Design Professionals” and “Sustainability Orientation in Design Students”, indicating a significant effect and an value of 0.211 for the relationship between “Sustainability Orientation” and “SS Orientation in Design Students” (which corresponds to a moderate effect). These metrics allow us to understand that each construct’s magnitude influences the other within the model (Hair et al., 2019b).

Table 4 presents the results of the structural model, including the values of path coefficients (), t-values, and p-values. As can be seen, the Hi1 and Hi3 hypotheses are supported by significant and positive relationships. The Hi1 hypothesis (PSS -> OS) showed a path coefficient of 0.509 (t = 7.796; p < 0.001), while the Hi3 hypothesis (OS -> OSS) had a coefficient of 0.453 (t = 6.347; p < 0.001). However, the Hi2 hypothesis (PSS -> OSS) did not reach statistical significance ( = 0.127; t = 1.507; p = 0.132), so it was not supported in this model. The results confirmed the acceptance of the Hi1 and Hi3 hypotheses, which show a positive and significant relationship between the constructs studied, as established by the criterion of (Chin, 1998) for structural models.

Table 4.

Summary of the results for the hypothesis testing of the measurement model.

7. Discussion

7.1. Theoretical Discussion

The results of the structural model show a significant relationship between social sustainability (SS) practices in design professionals and orientation toward sustainability in students (Hi1, = 0.509, p < 0.001). This finding is consistent with the Institutional Theory of (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983), which suggests that the norms of the professional environment influence the values that the students adopt in their training. In addition, an alignment with the Capabilities Approach of (Sen, 1993) was observed, emphasizing that developing competencies such as equity and inclusion is vital to long-term well-being in the educational and professional spheres, therbey providing a solid foundation for developing a culture of SS in graphic design.

7.2. SS Practices and Sustainability Orientation

The Hi1 hypothesis also reinforces the notion that SS professional practices influence sustainability orientation among design students, which aligns with the work of (Marshall et al., 2015) (who highlighted how observing social justice practices inspires students with a culture of sustainability). The values for “Sustainability Orientation in Design Students” (0.26) and the effect size (0.35) indicate a moderate predictive power and a strong effect of SS practices on sustainability orientation. These findings confirm that design professionals’ engagement with SS can significantly influence the development of sustainable values among students.

7.3. SS Practices and SS Orientation

Although the direct relationship between SS practices and SS orientation in students was not confirmed (Hi2, = 0.127, p = 0.132), the indirect impact is relevant when considering the influence of the general orientation to sustainability on the development of a specific orientation to SS (Hi3, = 0.453, p < 0.001). This result is aligned with the Capabilities Approach of (Sen, 1993), which highlights the importance of an educational environment that fosters values of social cohesion and well-being. The indirect influence observed on the orientation toward SS suggests that the initial commitment to general sustainability can facilitate the focus on social aspects, as shown by previous research (Corsini & Moultrie, 2021; Lee, 2021).

7.4. Orientation to Sustainability and Orientation to SS

The positive and significant relationship between sustainability orientation and SS orientation in students (Hi3) underscores the importance of first developing a general orientation toward sustainability and then strengthening a more specific focus on SS. The values of (0.28) and the effect (0.211) show that general orientation has a moderate impact on SS orientation, aligning with the studies of (Marshall et al., 2015) and (Missimer et al., 2017). These results highlight that students, by deepening their understanding of overall sustainability, also advance their engagement with issues of equity and social justice in design (Pakravan et al., 2022).

These findings reflect the persistent connection between graphic design teaching and contemporary societal challenges, suggesting a gap that has already been pointed out in the literature (Arno et al., 2022; Findeli, 2001). Although graphic design has the potential to act as an agent of change, its teaching continues to prioritize a technical and commercial approach, leaving aside critical dimensions such as inclusion, equity, and social justice. This gap translates into a fragmented pedagogy, where social issues may exist within graphic design education but are not necessarily linked to sustainability.

As suggested by (Nguyen & Mougenot, 2022), graphic design operates within a broader socioeconomic system. However, its disciplinary delimitation restricts the possibility of integrating interdisciplinary frameworks that favor a holistic understanding of its social impact. Cases such as those documented by (Gamba, 2023) show that, in urban environments, design can generate community cohesion through participatory strategies. However, this requires a rethinking of teaching that transcends the visual domain to engage with systemic issues. However, the evolution of this pedagogy faces structural resistance, such as curricular rigidity and the lack of spaces for collaboration with disciplines such as sociology or economics, which limits the ability of designers to assume a broader social responsibility. Faced with these challenges, graphic design education must critically question its role and redefine the competencies it prioritizes in the training of future professionals, ensuring that they communicate messages and understand and transform their environment from a sustainable and equitable perspective.

8. Conclusions

This study, from the perception of graphic design students, shows that design professionals’ social sustainability (SS) practices positively influence student orientation toward sustainability in general and SS in particular. The findings highlight that observing professional practices generates, in students, a predisposition to integrate aspects of social justice, inclusion, and well-being into their projects. Although no significant direct relationship was found between professional practices and a specific orientation toward SS, the indirect impact of general orientation to sustainability on SS underscores the relevance of first fostering a broad focus on students. These results are aligned with the theories of (Sen, 1993) and (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983), underlining the importance of an academic and professional environment that promotes social responsibility in the training of future designers.

The findings of this study reinforce the need for a transformation in the teaching of graphic design, particularly in its link with social sustainability. Despite the growing recognition of the role of design in inclusion, equity, and urban regeneration, educational structures continue to prioritize technical and commercial approaches, limiting the training of designers with a critical and systemic perspective. This disconnect suggests that pedagogical evolution requires profound changes, not only in integrating interdisciplinary frameworks, but also in a redefinition of the essential competencies designers need to operate within complex socioeconomic systems. Thus, the challenge lies in incorporating content on social sustainability into the curricula and rethinking the role of graphic design as a discipline that, beyond visual communication, must assume an active responsibility in social transformation and sustainable development.

9. Educational Implications and Prospects

This research suggests that design programs should integrate an explicit SS approach into their curricula, promoting exposure to actual and simulated practices involving social justice, equity, and social cohesion. Educational institutions can adopt pedagogical strategies that promote collaborative projects with design professionals, allowing students to observe and assimilate SS practices. Additionally, promoting competencies in social sustainability could be addressed in subjects of professional ethics and community development, integrating theories such as (Sen, 1993) to support a culture of social empowerment from academia.

The findings of this study open several lines of research, such as exploring how social sustainability (SS) practices in design adapt and vary in different cultural and educational contexts and assessing the stability of relationships observed in other countries. In addition, comparing the impact of SS practices taught by teachers versus those observed in professionals is suggested to identify which are more effective in forming socially sustainable values. Longitudinal research would also be helpful to understand how these orientations evolve in design students over time and at what point SS values are consolidated, as well as the role of educational technologies, such as simulation, in strengthening the development of a culture of sustainability in design.

10. Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, it was based on a geographically limited sample, which can affect the generalizability of the results. In addition, using a cross-sectional design limits the ability to observe how orientations toward sustainability develop over time. Future research could take a longitudinal approach and expand the sample to other regions or countries to assess whether these relationships hold in diverse cultural and educational contexts. Finally, although the relevance of the general orientation in sustainability was demonstrated, it would be valuable to explore other factors, such as the role of teachers, in developing a culture of SS in design students.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B.-G. and M.R.-C.; methodology, D.B.-G., B.L.D.-M., and M.R.-C.; software, M.R.-C.; validation, B.L.D.-M., E.A.-S., L.A.B.-G., and A.G.-G.; formal analysis, M.R.-C., B.L.D.-M., and E.A.-S.; investigation, D.B.-G.; resources, B.L.D.-M., E.A.-S., L.A.B.-G., and A.G.-G.; data curation, M.R.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, B.L.D.-M., E.A.-S., L.A.B.-G., and A.G.-G.; writing—review and editing, E.A.-S., D.B.-G., and M.R.-C; visualization, M.R.-C.; supervision, B.L.D.-M., E.A.-S., L.A.B.-G., and A.G.-G.; project administration, D.B.-G. and M.R.-C.; funding acquisition, B.L.D.-M., E.A.-S., L.A.B.-G., and A.G.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Not available. The managers interviewed agreed to respond under confirmation that the information would be kept confidential.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Instrument.

Table A1.

Instrument.

| 1. SS practices in Design Professionals (PSS) |

|---|

| 1.1. Health is a recurring theme in design projects in my region. |

| 1.2. Emotional care is a recurring theme in design projects in my region. |

| 1.3. Social security is a recurring theme in design projects in my region. |

| 1.4. Human rights is a recurring theme in design projects in my region. |

| 1.5. Gender equity is a recurring theme in design projects in my region. |

| 1.6. Inclusion is a recurring theme in design projects in my region. |

| 1.7. Social cohesion is a recurring theme in design projects in my region. |

| 2. Orientation to Sustainability in Design Students (OS) |

| 2.1. The issue of sustainable development is crucial. |

| 2.2. My projects are more and more related to sustainability issues. |

| 2.3. I understand the concepts of sustainability more and more. |

| 2.4. My design concepts have exceptional attention to environmental aspects. |

| 2.5. My design concepts have exceptional attention to social aspects. |

| 3. Orientation to SS in Design Students (OSS) |

| 3.1. I clearly understand the difference between the concept of environmental sustainability and social sustainability. |

| 3.2. I have sufficient information about social sustainability in the field of design. |

| 3.3. I have a clear notion about social sustainability in the design sector. |

| 3.4. I have sufficient information to explain social sustainability in my profession. |

References

- Arno, V. G., Affifi, R., Willis, A., & Hildmann, J. (2022, November 2–4). Design, storytelling, and our environment: Critical insights from an empirical study with storytellers [Conference session]. Design for Adaptation: Cumulus Conference Proceedings (pp. 42–53, Lazet, A., Ed. ), Detroit, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, S., & Soygeniş, M. D. (2019). A design studio experience: Impacts of social sustainability. Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research, 13, 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling (Vol. 295, pp. 295–336). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colantonio, A., & Dixon, T. (2011). Social sustainability and sustainable communities: Towards a conceptual framework (pp. 18–36). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsini, L., & Moultrie, J. (2021). What Is Design for Social Sustainability? A Systematic Literature Review for Designers of Product-Service Systems. Sustainability, 13, 5963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N., Bramley, G., Power, S., & Brown, C. (2011). The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustainable Development, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R. F., & Miller, N. B. (1992). A primer for soft modeling (pp. 103–xiv). University of Akron Press. [Google Scholar]

- Findeli, A. (2001). Rethinking design education for the 21st Century: Theoretical, methodological, and ethical discussion. Design Issues, 17, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Foladori, G. (2005). Advances and Limits of Social Sustainability as an Evolving Concept. Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue Canadienne d’études Du Développement, 26, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamba, S. (2023). Participatory public art and creative workshop: Murals in Bergamo’s suburbs. Documenti Geografici, 2, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladwin, T. N., Kennelly, J. J., & Krause, T. S. (1995). Shifting paradigms for sustainable development: Implications for management theory and research. Academy of Management Review, 20, 874–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Castillo Apraiz, J., Cepeda Carrión, G., & Roldán, J. L. (2019a). Manual de Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) (Segunda Ediciόn). OmniaScience. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Ringle, C. M., Gudergan, S. P., Apraiz, J. C., Carrión, G. A. C., & Roldán, J. L. (2021). Manual avanzado de Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). OmniaScience. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019b). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S. W., Kim, H., Song, Y., Yoon, S. H., & Lee, J. (2020). Effects of Human Behavior Simulation on Usability Factors of Social Sustainability in Architectural Design Education. Sustainability, 12, 7111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, M., & Sutherland, J. (2008). An exploration of measures of social sustainability and their application to supply chain decisions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 16, 1688–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P. D., & Hoffman, A. J. (2021). Three paradoxes of climate truth for the anthropocene social scientist. Organization & Environment, 34, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R., & Tonts, M. (1995). Rural restructuring and social sustainability: Some reflections on the western australian wheatbelt. Australian Geographer, 26, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazamia, K. I., & Kafaridou, M. (2019). The integration of social issues in design education as a catalyst towards social sustainability. European Journal of Sustainable Development, 8, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keynoush, S., & Daneshyar, E. (2022). Defining a pedagogical framework for integrating buildings and landscapes in conjunction with social sustainability discourse in the architecture graduate design studio. Sustainability, 14, 4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. (2021). A Systematic Review on Social Sustainability of Artificial Intelligence in Product Design. Sustainability, 13, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Dijst, M., Geertman, S., & Cui, C. (2017). Social sustainability in an ageing chinese society: Towards an integrative conceptual framework. Sustainability, 9, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, V., Agrawal, R., Sharma, V., & Kavitha, T. (2016). Socially sustainable business practices in Indian manufacturing industries: A study of two companies. International Journal of Logistics Systems and Management, 24, 18–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, D., McCarthy, L., McGrath, P., & Claudy, M. (2015). Going above and beyond: How sustainability culture and entrepreneurial orientation drive social sustainability supply chain practice adoption. Supply Chain Management, 20, 434–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, S., & Hawke Research Institute, University of South Australia. (2004). Social sustainability: Towards some definitions. Hawke Research Institute, University of South Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Missimer, M., Robèrt, K. H., & Broman, G. (2017). A strategic approach to social sustainability—Part 1: Exploring the social system. Journal of Cleaner Production, 140, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M., & Mougenot, C. (2022). A systematic review of empirical studies on multidisciplinary design collaboration: Findings, methods, and challenges. Design Studies, 81, 101120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opp, S. (2017). The forgotten pillar: A definition for the measurement of social sustainability in American cities. Local Environment, 22, 286–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakravan, S., Keynoush, S., & Daneshyar, E. (2022). Proposing a pedagogical framework for integrating urban agriculture as a tool to achieve social sustainability within the interior design studio. Sustainability, 14, 7392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J. M. (2024). SmartPLS 4. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Rogers, D., Duraiappah, A., Antons, D., Munoz, P., Bai, X., Fragkias, M., & Gutscher, H. (2012). A vision for human well-being: Transition to social sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 4, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekeran2013p. (2013). Research methods for business: A skill-building approach. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 34, 700–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. (1993). Development as Expansion of Capabilitie I O desenvolvimento como expansão de capacidades. Lua Nova: Revista de Cultura e Política. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallance, S., Perkins, H., & Dixon, J. (2011). What is social sustainability? A clarification of concepts. Geoforum, 42, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacker, J. G. (1998). A definition of theory: Research guidelines for different theory-building research methods in operations management. Journal of Operations Management, 16, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarghami, E., Fatourehchi, D., & Karamloo, M. (2017). Impact of daylighting design strategies on social sustainability through the built environment. Sustainable Development, 25, 504–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).