1. Introduction

Grade retention, the practice of requiring a student to repeat a grade, is a controversial topic in educational policy and practice. Commonly implemented to force those who do not comply with an educational system’s desired academic benchmarks to reach the desired competencies, it remains a practice whose effectiveness and consequences continue to be debated. Likewise, its application largely depends on the perceptions about grade retention of those who decide how to manage heterogeneity within educational systems and schools.

Within schools, student heterogeneity comes from different abilities, motivations and personal objectives, which can be related to different sociocultural backgrounds. In light of this, education systems worldwide use different practices to manage this heterogeneity within schools and classrooms (

Dupriez et al., 2008;

Hermann & Kopasz, 2021).

The practices most often used to manage heterogeneity worldwide are tracking, ability grouping, personalized teaching practices and grade retention (

Hermann & Kopasz, 2021;

Mons, 2007). Tracking and grouping allow students to be classified by ability, motivation or other variables, creating more homogeneous groups. In theory, this improves the chances for low- and high-performance students to receive appropriate teaching for their learning level (

Deunk et al., 2018). Individualized teaching practices imply teachers’ dedication of more time and attention to students with lower achievement levels (

Demanet & Van Houtte, 2019;

Dupriez et al., 2008). In contrast, Grade retention artificially decreases the degree of heterogeneity within classes by holding back students who do not meet a minimum required standard of achievement or maturity (

Hermann & Kopasz, 2021).

It is necessary to highlight that the current literature has identified earlier retention, low achievement scores, the number of years being retained, behavioral problems, the degree of parental involvement, low attendance, being male, and socio-economic situation as some of the main factors that increase the probability of repeating a grade (

Huang, 2014;

Jimerson, 2001;

Jimerson et al., 1997;

Meriño-Montero, 2021;

Valbuena et al., 2021). Similarly, the research on grade retention has supported a variety of perspectives regarding the effects associated with this mechanism, ranging from claims of short-term academic improvement to long-term detriments to emotional and motivational well-being and reduced likelihood of university enrolment. (

Díaz et al., 2021;

Goos et al., 2021;

Valbuena et al., 2021;

Van Canegem et al., 2024;

Vandecandelaere et al., 2016), as well as no effects or differences from their promoted peers (

Pipa et al., 2024). Likewise, academic retention would significantly impact students’ lifelong outcomes and future societies, considering that it is directly associated with a lower probability of entering university (

Santos et al., 2023a;

Van Canegem et al., 2024).

Considering the wide variety of empirical findings, the importance of understanding grade retention practice, its impact on students, and the factors and perceptions that shape its implementation cannot be understated.

As educational systems globally struggle to balance policy and practice that maintain standards while supporting student growth, educator perspectives on grade retention play a significant role in shaping policy and practice. For this reason, it is important to highlight that empirical research has found that teachers’ beliefs can significantly influence the application of national educational policies and new regulations, shaping how they interpret and implement reforms (

Cipriano & Martins, 2021;

Fives & Buehl, 2016).

The literature makes it clear that educators’ beliefs about grade retention not only reflect personal experiences and biases, but also respond to the broader educational context (

Santos & Monteiro, 2024;

Tomchin & Impara, 1992;

Walton, 2018). Teachers’ beliefs are particularly important, as they directly influence retention decisions and interact with systemic factors that may determine or increase the probability of grade retention (

Feathers, 2020;

Kerr, 2007;

Walton, 2018;

Young et al., 2019). Exploring these beliefs in greater depth can provide valuable insights into the mechanisms that shape grade retention practices within an educational system.

Building on this foundation, our study’s main objective is to adapt and validate a scale to assess 4th-grade teachers’ perceptions of the impact of grade retention on educational trajectories, focusing on measuring their beliefs about the consequences of grade retention. The scale was developed based on items selected from the Grade Retention Survey originally developed by

Manley (

1988). Additionally, we aim to examine how teachers’ beliefs about grade retention, as measured by the new scale, are influenced by individual and school-level variables (e.g., gender, administrative dependence, socioeconomic status, among others). By doing so, we seek to provide insights into how these beliefs shape and are shaped by the Chilean educational and institutional context, particularly to implement inclusive policies.

Challenging Traditional Perspectives: How a New Public Policy Seeks to Shift Beliefs on Grade Retention in Chile

In Chile, renewed attention to grade retention practices has emerged with the recent implementation of Decree 67 (

MINEDUC, 2018). This Decree has brought a heightened examination of existing practices and the potential effects of this policy shift. In 2018, with the calling of the bill that “Approves minimum national standards on evaluation, qualification and promotion” (Decree 67,

MINEDUC, 2018), a new conceptual framework for grade retention was established, which began to take effect from 2020 onward and, for the first time, eliminated automatic grade retention. For nearly a century, Chile’s education system maintained a largely unchanged set of rules on retention and promotion, even as student evaluation standards evolved over time (

Allende et al., 2024b).

The new Decree 67 does not explicitly prohibit grade retention but specifies that it should be employed only as an exceptional measure by principals and/or director teams. Unlike previous decrees, which mandated automatic criteria for grade retention, the new decree requires a more comprehensive approach. It emphasizes that all relevant information about the students must be considered during the decision-making process, with a primary focus on their well-being. The decree stipulates that the final decision should account for the student’s learning progress and the extent of their learning gaps, as well as the perspectives of teachers, parents, and students.

Schools must develop assessment, grading, and promotion regulations detailing how they will handle situations where students do not achieve the required knowledge or development, focusing on their well-being and comprehensive development (

MINEDUC, 2019). This shift highlights a broader commitment by the government to fostering inclusive and supportive learning environments that address both academic and socio-emotional needs (

Valenzuela & Allende, 2023).

However, this new regulation contrasts with the empirical evidence about teacher beliefs in Chilean schools, where most teachers blame school failure on the students themselves and their parents (

Román, 2013;

Treviño et al., 2016;

Meyer, 2022). Only a very low percentage of teachers relate failure to how knowledge is delivered by them and the school, or with the quality of teaching in the classroom (

Román, 2013). Additionally, there is a prevailing belief or ideology of “demandingness

” (

García-Huidobro, 2000), in which a “good teacher” is perceived as one who fails a larger number of students, while a “bad teacher” is seen as someone who promotes everyone.

This educational system has historically promoted and positively valued the administration of exclusionary practices (

López et al., 2024), such as grade retention. At the same time, many families do not view learning or comprehensive education as the primary goal of schooling. Instead, they value student promotion regardless of whether actual learning is taking place (

García-Huidobro, 2000).

The new Decree is introduced in an educational system where grade retention has been made almost invisible by the authorities by failing to provide easy-to-access data about the magnitude of this practice, the factors associated with the likelihood of repeating a year, and the associated effects.

In terms of magnitude, average grade retention rates in primary education have remained below 5% since 2002, reaching a historic low of under 2% in 2022. In secondary education, retention rates have generally stayed below 10% since 2002, with the exception of 2006 and 2011, when massive demonstrations caused a temporary spike. These rates then continuously declined, reaching approximately 3.5% by 2022. However, a broader perspective emerges when examining the cumulative percentage of students who have repeated a grade during their educational trajectory. By 2022, approximately 6% of students in the first cycle of primary education (1st–4th grade) and 12% in the second cycle (5th–8th grade) had repeated at least one grade, compared to 18% across Latin America (

UNESCO, 2021). In secondary education, 21% of students in 2022 had repeated a grade, lower than the 23.2% reported for Chile in the PISA test but significantly higher than the OECD average of 11% (

OECD, 2020).

All of this shows us that schools, as well as teachers, could be predisposed to continue with this practice, simply out of habit. As

García-Huidobro (

2000) mentions, “The functioning of the school cannot be understood without the adhesion of its members and users. Since there is a deep-rooted cultural conviction about the advantages of grade retention, it would not be effective to abolish retention by decree. Before that, it is necessary to wage an important cultural fight to change the prevailing perceptions among us” (p. 6).

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

We adapted and analyzed a questionnaire that gathered perceptions about grade retention from elementary school teachers. Our research team submitted the questionnaire applied to the “Call for Researchers to Propose Questions for Quality and Context of Education Surveys” for the 2023 Chilean school system’s standardized tests (Sistema de Medición de la Calidad de la Educación [SIMCE]). SIMCE is a national test that assesses academic achievement in reading and mathematics. It is applied every year to fourth-grade students and alternately to sixth-, eighth-, and tenth-grade students (

Allende et al., 2024a), this includes complementary questionnaires for teachers, principals, families, and students.

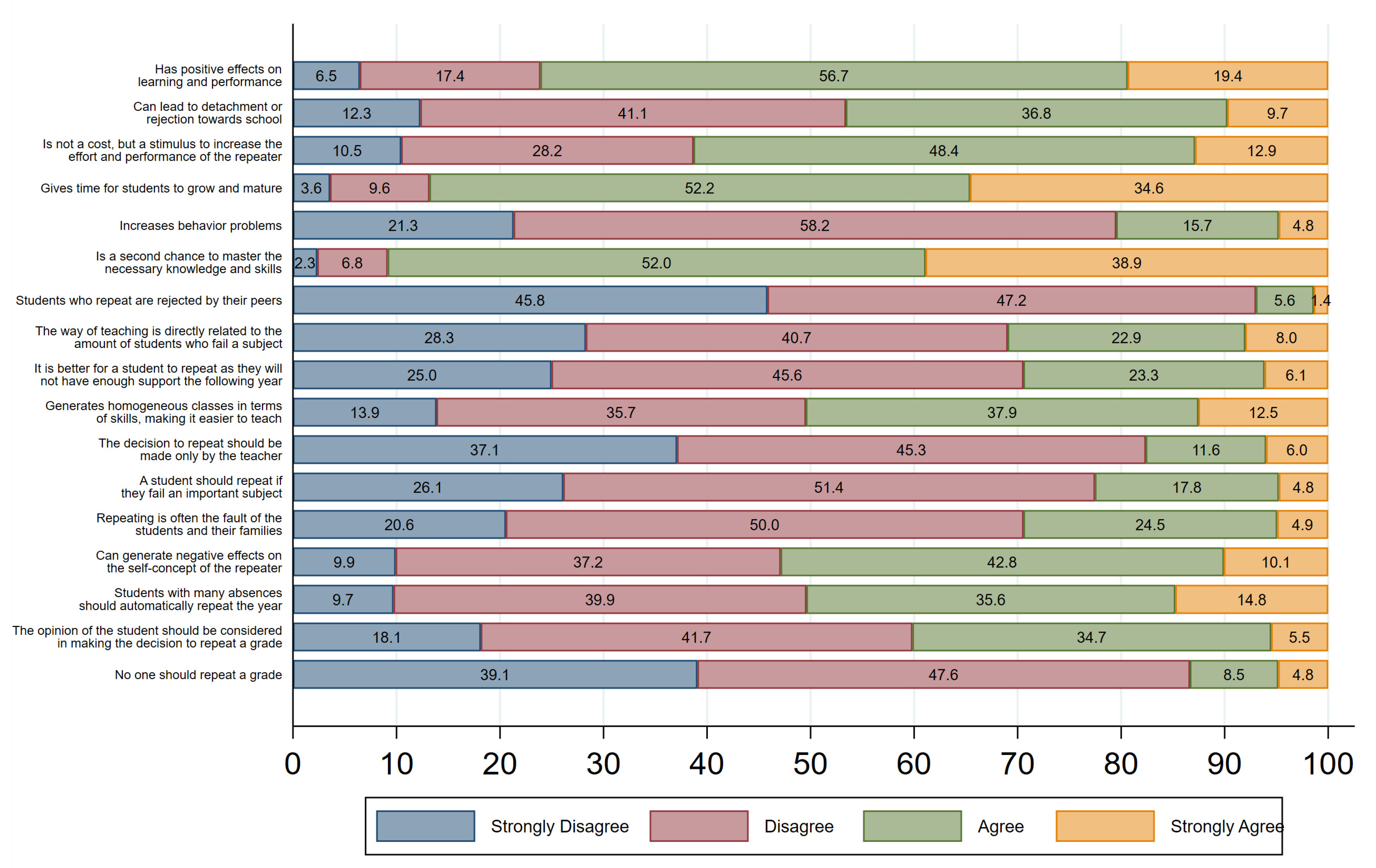

The project titled “Perceptions of School Repetition in the Context of Implementing Decree 67” was selected for this purpose, allowing us to include 17 items in the complementary questionnaires for teachers of 4th grade applied in person together with the SIMCE national test during November 2023.

3.2. Participants

The Education Quality Agency administered the questionnaire to all Chilean head fourth-grade teachers as part of the complementary teachers’ survey conducted alongside the SIMCE 2023 national test. To access the public databases, a formal request must be submitted through the official website of SIMCE (See Data Availability Statement). The total number of surveyed teachers who completed the items on perceptions of grade retention was 4297 observations.

According to the State of Chile’s protocols for handling personal data, all datasets used had a blind personal identifier provided by the Education Quality Agency. The identifier allows blind access to the responses of all teachers, safeguarding the confidentiality of the information used. At the same time, this dataset allows cross-referencing such data with data at the school level existing in Chile.

3.3. Instrument

The survey instrument used was an adaptation of The Grade Retention Survey, originally developed by

Manley (

1988). This instrument was selected primarily because it has been widely used in numerous studies over time since its publication (e.g.,

Feathers, 2020;

Kerr, 2007;

Richardson, 2010) but, to the best of our knowledge, has never undergone a formal validation process.

This survey originally consisted of 35 items on teachers’ perceptions and beliefs about grade retention, measured using a six-option Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”, with a reliability of 0.72 measured by Cronbach’s Alpha (

Manley, 1988). For the present study, we selected a series of items from the version of this questionnaire applied by

Feathers (

2020), which consisted of 27 items, where some questions were rephrased from the original version of the survey. We include 14 items from the original scale. The selected items were focused on the perceived consequences of grade retention and perceptions regarding who should bear the responsibility for applying this type of sanction.

In addition to the selected 14 items from the original questionnaire, 3 items relevant to the Chilean context were added. These questions specifically addressed whether teachers associate their teaching methods with the number of students who repeat a grade and their perceptions of who is responsible for academic failure. These specific questions are relevant to the Chilean reality, considering that the limited research available for Chile has shown that only a very low percentage of teachers relate failure to how knowledge is delivered by them and the school or with the quality of teaching in the classroom (

Román, 2013;

Meyer, 2022). Likewise, it is important given the meritocratic discourse in Chile, where they are led to believe that their personal effort is the sole explanation for educational success and school failure (

Peña & Toledo, 2017). Additionally, teachers were asked whether the availability of complementary support could determine grade retention, as the new Decree 67 explicitly states that students repeating a grade must receive academic support.

The selected items were initially translated, rephrased, and reviewed by the research team. This translation was reviewed by three educational research experts, who validated the initial translation. Additionally, a third review was conducted by the staff of the Education Quality Agency, which administered the final questionnaire. Both revisions provided us with suggestions to improve understanding and application of the questionnaire. This process refined the wording and enhanced the phrasing of some questions when translated into Spanish, ensuring the correct application of the new questionnaire.

The original scale was adjusted to a four-option Likert scale (Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Agree, Strongly Agree). This avoids neutral responses and forces teachers to choose an option concerning the provided alternatives.

Table A3 in

Appendix A.2 shows all the items included in Spanish, and

Table A4 in

Appendix A.2 provides a direct English translation of the items.

3.4. Data Analysis

First, a descriptive inspection of the items was carried out to determine their level of discrimination. This was done to confirm whether the item-scale relationship was above 0.3 for all considered items, the minimum threshold to ensure sufficient discrimination (

Robinson et al., 1991, p. 13). The reliability of the scale was assessed by calculating Cronbach’s Alpha with standardized items and McDonald’s Omega, using the polychoric correlation matrix to account for the ordinal nature of the items (

Flora, 2020;

Hayes & Coutts, 2020). Values greater than 0.8 for both Cronbach’s Alpha and McDonald’s Omega were considered indicative of a robust measurement instrument (

Intimayta-Escalante et al., 2025;

DeVellis, 2017;

Reise et al., 2013;

Robinson et al., 1991, p. 13). Additionally, this inspection verified that all items had the same direction; if this condition was not met, the direction of the variable in question was reversed.

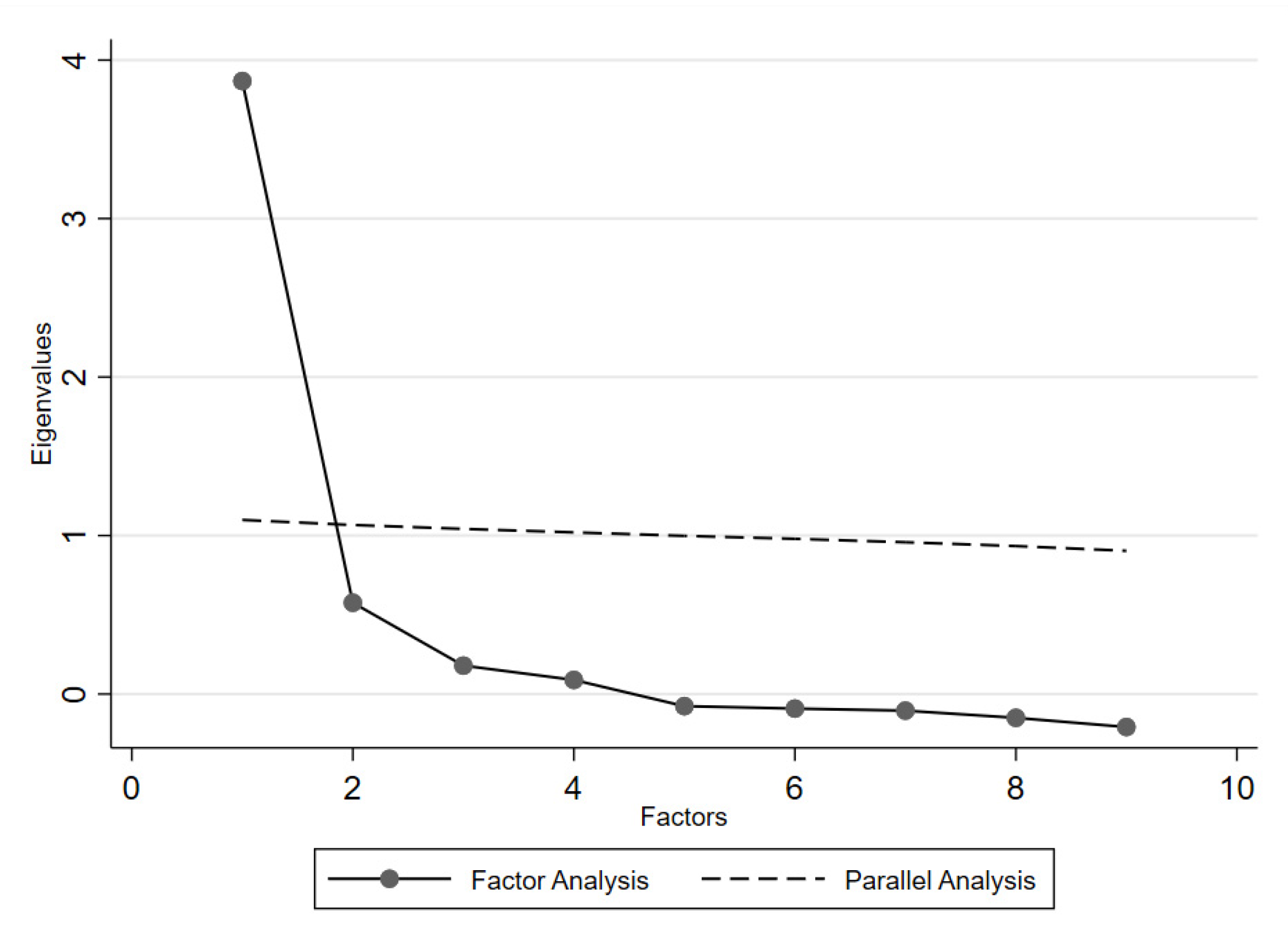

Subsequently, the methodology followed is the EFA within CFA framework (E/CFA) proposed by Jöreskog (

Brown, 2015;

Jöreskog, 1969;

Sanders et al., 2015;

Sullivan & Davila, 2022). Jöreskog’s E/CFA methodology begins with estimating an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), which in this case, was conducted using the principal factor method. For this analysis, we consider only the 14 items that belong to the original scale developed by

Manley (

1988).

Then, since all the items considered were categorical, the Polychoric correlation matrix is used in the analysis to obtain robust estimates (

Kolenikov & Angeles, 2009). The number of factors selected is determined through the parallel analysis method (

Humphreys & Montanelli, 1975). Then, to define the type of rotation to use, the correlation matrix between the items is checked to see whether it showed high correlations (

Tabachnick et al., 2019). The matrix displayed moderate and high correlations among many variables (see

Appendix A.3,

Table A5), leading to the decision to use oblimin rotation (

Hair et al., 2019).

Next, the variables associated with each factor were selected based on the obtained factor loadings, selecting those with loadings greater than 0.5. This follows the recommendations of

Hair et al. (

2019), ensuring that each factor explains at least 25% of the variance for each variable included in it, which, according to the authors, practically guarantees the significance of the factor loadings.

Finally, the structure found was tested using a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to verify whether the fit indices obtained met the ranges considered acceptable according to the literature: CFI and TLI very close to 1; RMSEA less than 0.06; SRMR close to zero and never exceeding 0.08; likewise, with chi-square to degrees of freedom ratios generally less than 3 (

Brown, 2015;

F. Chen et al., 2008;

Hair et al., 2019). The diagonal weighted least squares (DWLS) method was used to estimate the CFA parameters. This method produces robust standard errors and adjusts for the lack of normality in the Likert scale used.

To assess cross-validation, which aims to evaluate whether the model obtained is robust and generalizes well to new data, thus preventing overfitting (

Brown, 2015) and additionally enabling us to refine the final model and confirm its validity. The model was initially trained on a subset consisting of 50% of the sample (training set; N = 2148) and subsequently tested (validated) on the remaining 50% (test set; N = 2149). The model’s structure was first estimated using the EFA on the training set, followed by the final CFA estimation on the test set. Once the final model was validated, it was re-estimated using the entire sample of fourth-grade teachers (model retraining). With more observations, the goal was to achieve greater robustness in the final estimations.

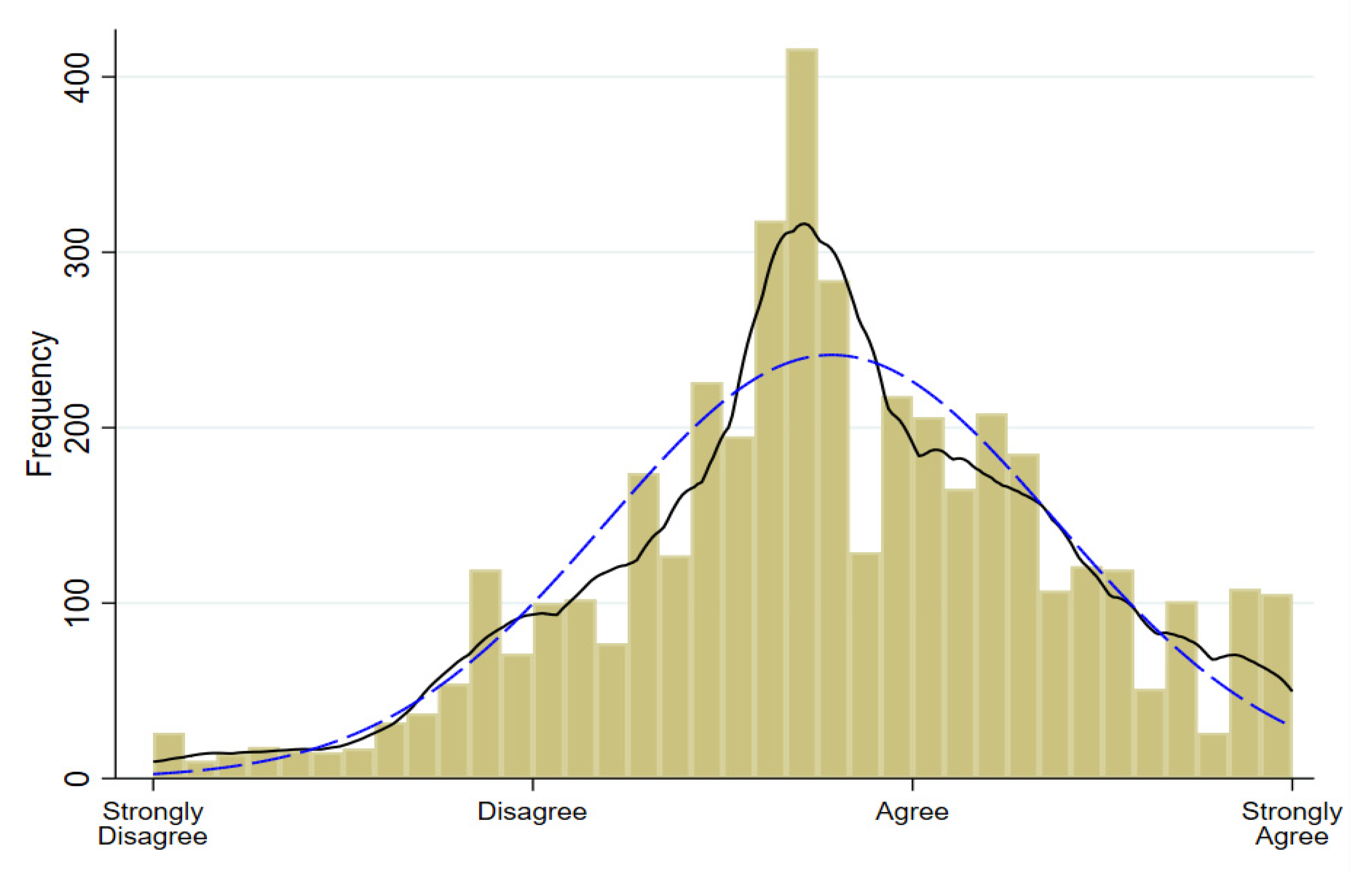

The factor scores were subsequently predicted from the CFA model for the entire sample of fourth-grade teachers. These scores represent teachers’ perceptions of the effects of grade retention on students, which from now on will be referred to as the Beliefs on Consequences of Retention scale (BCR scale), in order to make construct validation clearer, in terms of what the instrument is actually measuring. The final scale was standardized to have a minimum of 1 and a maximum of 4, aligning it similarly with the Likert scale used for all the items (1 “Strongly disagree”; 2 “Disagree”; 3 “Agree”; 4 “Strongly agree”). A higher score on the scale implies that teachers’ perceptions of grade retention are more positive. In other words, it will indicate whether teachers view grade retention mostly as an opportunity for improvement and growth over time. On the other hand, lower scores will indicate whether they perceive it as an experience that could negatively affect emotional well-being, school trajectories, or the connection with the school.

To test measurement invariance, we employed Multigroup Confirmatory Factor Analysis (

Cheung & Rensvold, 2002;

Hair et al., 2019). This involved testing for configural, metric, and scalar invariance, as “support for scalar invariance is required if any comparisons of relative construct level (e.g., mean scores) are made across groups. That is, scalar invariance allows the relative amounts of latent constructs to be compared between groups” (

Hair et al., 2019, p. 739), which was the final comparison conducted in this study.

We evaluated changes in model fit using multiple indicators, including differences in CFI (ΔCFI), RMSEA (ΔRMSEA), SRMR (ΔSRMR), and TLI (ΔTLI). Measurement invariance was assessed based on the following cut-off criteria: ΔCFI ≤ 0.010, ΔRMSEA ≤ 0.015, and ΔTLI ≤ 0.010. For ΔSRMR, the thresholds were ≤0.03 for metric invariance and ≤0.01 for scalar invariance (

Intimayta-Escalante et al., 2025;

Khademi et al., 2023;

Tian et al., 2022;

F. F. Chen, 2007;

Cheung & Rensvold, 2002).

Finally, after estimating the BCR scale, the predicted index was analyzed in relation to individual and school variables through ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) to determine potential associations between the constructed scale and other variables. The ANOVA method was used to assess whether there were statistically significant differences in the BCR scale across different groups based on individual and school variables.

Among the individual variables, the analysis included gender (a dichotomous variable coded as 1 for female), beliefs about the relationship between grade retention and teaching methods, the presence of support or companionship, and the perception that grade retention is the responsibility of parents and families. As previously described, these variables were measured on a four-option Likert scale (Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Agree, Strongly Agree).

The school-level characteristics considered included administrative dependence (i.e., public, private-subsidized, and private paid), the socioeconomic level scale constructed by the Education Quality Agency based on family characteristics (i.e., Low, Middle-Low, Middle, Middle-High, High), and the grade retention rate in the first cycle of primary education (grades 1 to 4), which was incorporated into the estimations using tertiles of the school grade retention rate.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to validate the selected items from the SIMCE questionnaires on teachers’ perceptions of grade retention, included under the project “Perceptions of School Repetition in the Context of Implementing Decree 67”. For this purpose, 14 items were initially considered, and it was possible to determine the existence of a single unidimensional construct composed of six items, which adequately represent the Beliefs on Consequences of Retention (BCR scale) for elementary school teachers in Chile.

The reliability, discrimination measures, and validation of the internal consistency of the items considered confirm that the estimated construct has strong properties and can serve as a reliable scale for measuring the beliefs on the consequences of grade retention. Additionally, the unidimensional structure was tested through a CFA, which demonstrated a good fit for the items comprising this construct.

The results obtained regarding the BCR scale showed that contextual factors such as school retention rates, administrative dependence, and socioeconomic status significantly shape teachers’ beliefs about grade retention. Our results regarding contextual factors strengthen the validity of the BCR scale, confirming the results obtained in previous research.

In particular, teachers working in schools with higher grade retention rates or serving lower socioeconomic communities tend to hold more negative beliefs about grade retention. This may reflect teachers’ greater reliance on grade retention as a measure to manage heterogeneity within different classrooms, a result consistent with findings documented in the literature (

Cipriano & Martins, 2021;

Santos et al., 2023b). In contrast, teachers in schools with low retention rates may have less supportive perceptions of retention, possibly due to a stronger focus on alternative educational strategies to manage student heterogeneity. As mentioned by

Protheroe (

2007) some of these alternatives could include enhancing teacher effectiveness by supporting them in diversifying their instructional approaches to meet the needs of lower-performing students and extending learning opportunities through supplementary programs, such as weekend classes, after-school sessions, and summer schools.

Conversely, we show that teachers in lower socioeconomic schools tend to have more negative perceptions of grade retention, suggesting that they may be more aware of the broader challenges faced by students from disadvantaged backgrounds. This result is also consistent with findings in the international literature (

Santos et al., 2023b;

Walton, 2018), which highlights how socioeconomic factors could influence teachers’ views about grade retention, as they are more likely to recognize the role that sociodemographic conditions play.

Regarding administrative dependence, our results show that teachers in public schools hold more negative beliefs about grade retention. This disparity in viewpoints between various types of schools demonstrates the influence of institutional context on teachers’ attitudes towards grade retention, a result that has also been supported in the literature (

Santos & Monteiro, 2024;

Walton, 2018). Specifically, it is likely that teachers in public schools may view grade retention more critically, possibly reflecting differences in student populations, resources, or institutional approaches to managing student heterogeneity.

The BCR scale showed significant gender differences in teacher beliefs, with female teachers showing more positive beliefs about the effectiveness of grade retention than their male counterparts, a finding that has also been reported in the international literature (

Santos & Monteiro, 2024). This result suggests that male and female primary educators may adopt different approaches when dealing with students with performance issues. These differences in perception could, in turn, influence their classroom practices and decision-making regarding how to support struggling students.

Concerning the items that sought to explore the Chilean reality, we found that the teachers’ beliefs about responsibility for student outcomes play a pivotal role in shaping their retention views. Our results could indicate that when teachers believe they don’t have any relation with poor student outcomes, they reveal much more positive beliefs toward grade retention. Thus, teachers who do not directly associate student retention with their actions and attitudes but rather with factors beyond their control hold more positive perceptions of grade retention. This could be because they consider grade retention as something beyond their control or something they cannot directly influence, thus reinforcing the belief that grade retention is an effective tool for managing student performance.

These findings align with the meritocratic discourse that prevails in the Chilean educational system, where individual effort plays a key role in students’ success or failure (

Peña & Toledo, 2017). This perspective not only places full responsibility on students and their families for academic failure but also removes accountability from schools and teachers. In line with the notion of negative reinforcement, teachers operating under this logic may overlook the potentially negative consequences of grade retention, such as emotional distress, disengagement from school, and damage to self-esteem (

Valbuena et al., 2021;

Kearney, 2008;

Goos et al., 2021;

Van Canegem et al., 2021).

On the other hand, belief systems applied to education are the ideas that teachers, students, or institutions hold about teaching, learning, and knowledge (

Wolf & Brown, 2023). These systems influence how teachers teach and interact with students, how students learn, and how the educational environment within the classroom is structured (

Muijs & Reynolds, 2002;

Sabarwal et al., 2022). Furthermore,

Santos et al. (

2023b) highlighted that teachers’ beliefs about grade retention are deeply intertwined with their broader psycho-pedagogical perspectives. These beliefs are embedded within a complex system encompassing views on learning, intelligence, assessment, and educational fairness.

Teacher beliefs, as defined by

Kagan (

1992), are a form of personal knowledge generally described as teachers’ implicit assumptions about students, learning, classrooms, and the subject matter to be taught, which are instrumental in determining the quality of interactions among teachers in a given school.

These beliefs—both implicit and explicit—that teachers hold about their students’ abilities and potential can affect how they interact with them, shaping classroom dynamics and influencing student outcomes (

Muijs & Reynolds, 2002). Thus, teacher beliefs become a fundamental part of the design and implementation of public policies, as they directly influence how the educational environment is structured (

Fives & Buehl, 2016;

Sabarwal et al., 2022).

Teachers’ perceptions are crucial when attempting to modify or change specific practices, like grade retention, because perceptions can lead to resistance to change. Since teachers are typically responsible for understanding and implementing the requirements of educational reforms, the impact of a progressive policy like Decree 67 could be diminished or even nullified if teachers’ perceptions do not align with the inclusive and progressive normative imposed by Decree 67.

The implementation of Decree 67, which aligns with global educational trends that seek to move away from punitive approaches to student failure, needs to consider these belief systems that exist in a more profound way, and more specifically, teachers’ beliefs about implementing the law. The decree should also emphasize the importance of robust support mechanisms and political consensus to ensure the successful integration of inclusive educational practices. Moreover, the challenges associated with its implementation underscore the need for sustained advocacy, comprehensive support systems, and cross-sectoral collaboration from the government to achieve its objectives. Additionally, it should prioritize the development of intervention strategies that focus on personalized support to guide teachers in making informed decisions, reducing reliance on intuition or personal beliefs.

By recognizing that grade retention should be an exception rather than the norm, Chile is aligning its policies with contemporary views on education that prioritize equity and the holistic development of students, taking their well-being into account rather than focusing solely on educational outcomes. To do this, it is necessary that all those involved in implementing this regulation align their beliefs, something that has not yet been achieved in Chile, as our results showed.

Finally, this study has produced a concise, validated instrument for assessing teachers’ beliefs about grade retention and its consequences. The instrument is a valuable tool for monitoring public policies aimed at reducing grade retention. It can provide insights into how teachers’ beliefs may influence the implementation and effectiveness of such policies and help assist in designing programs or interventions within schools to improve the implementation of these public policies.

The main drawback of this research is the potential presence of selection bias, as schools with high or low grade retention rates may also have distinct student populations, implement different programs, or be located in different geographical areas. These differences could lead to unobserved factors affecting the beliefs of teachers about grade retention. To partially address this issue, E/CFA with fixed effects at the school level could control for unobserved, time-invariant characteristics. However, the limited number of observations per school—since the survey was only completed by 4th-grade head teachers—does not allow us to carry out this estimation. Furthermore, we do not have a geographical grouping (e.g., neighborhood) sufficiently small to enable a fixed-effects model that adequately controls for unobserved variables at the geographical level. It is also important to note that this approach would not eliminate selection bias arising from non-random differences between groups.

We recommend that future research validates this instrument in secondary schools, as well as in other countries, to enhance its applicability and ensure its reliability across diverse educational contexts. Such efforts would ultimately contribute to more informed and inclusive approaches in education.