Prompting Theory into Practice: Utilizing ChatGPT-4 in a Curriculum Planning Course

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How do PSTs leverage ChatGPT-4 to link constructivist theory to practice in CP?

- (2)

- What are PSTs’ perceptions regarding the incorporation of ChatGPT-4 into CP?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Generative AI and Curriculum Planning

2.2. Research Context—Translating Constructivist Theory to Practice in a Curriculum Planning Course

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Part 1: Prompting Constructivist Theory into Practice

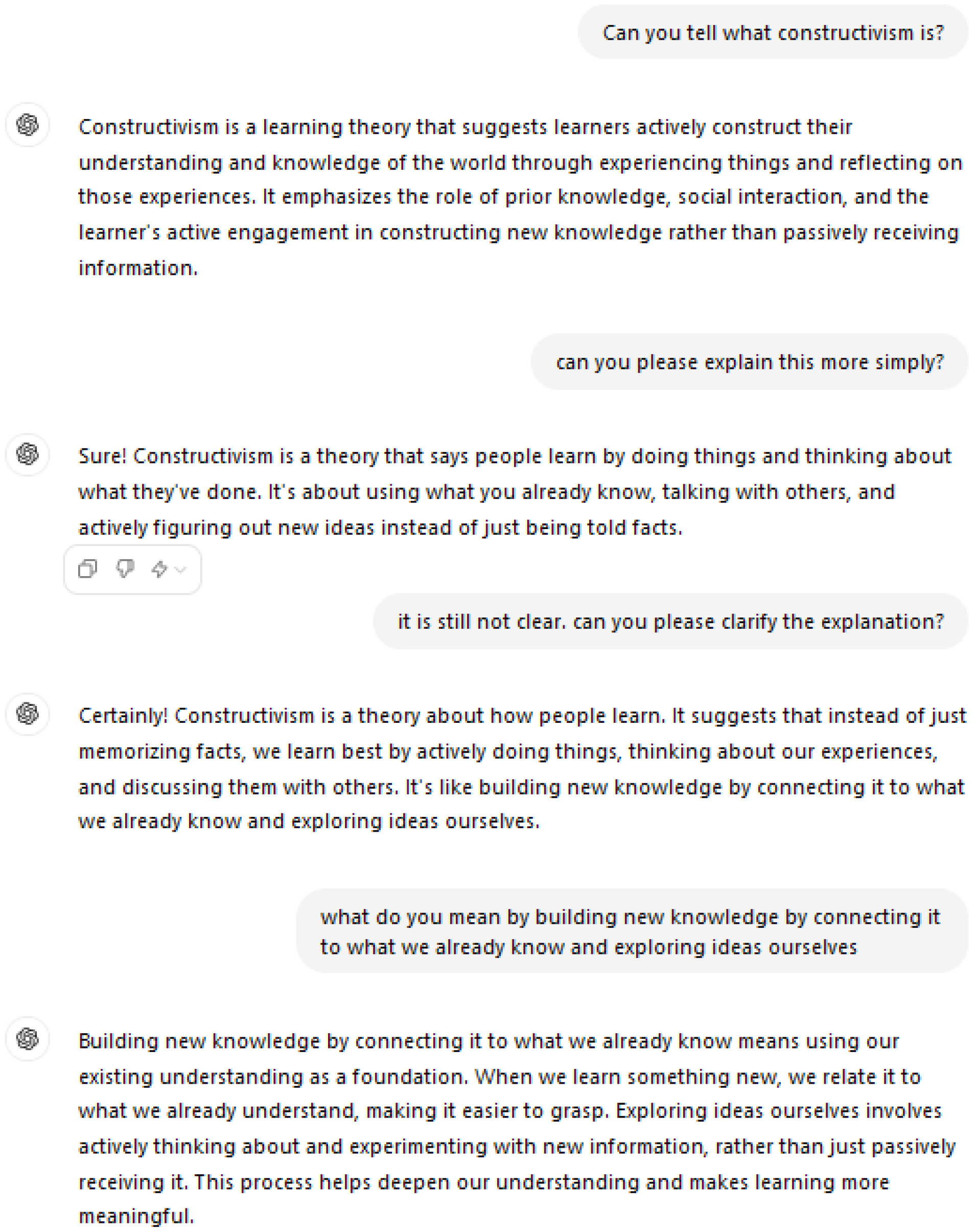

4.1.1. Simplifying Theory

I think that the power of ChatGPT is to explain complicated ideas simply and very clearly, so that everyone can understand (Interview 3).

I found it very difficult to understand constructivism. The articles we had to read were also complex. I felt that ChatGPT explained the theory in clearer words for me (Reflection 12).

I felt like I was talking to a real person who made things clear and used understandable language so I could understand it [constructivism] in the best way possible (Interview 7).

To be honest, asking the ChatGPT [about constructivism] didn’t really help me; it actually confused me. So I relied less on this tool and more on the course materials (Interview 5).

I find constructivism too abstract. Having a framework or checklist could serve as a guide to see if my curriculum planning reflects constructivist ideas (Interview 6).

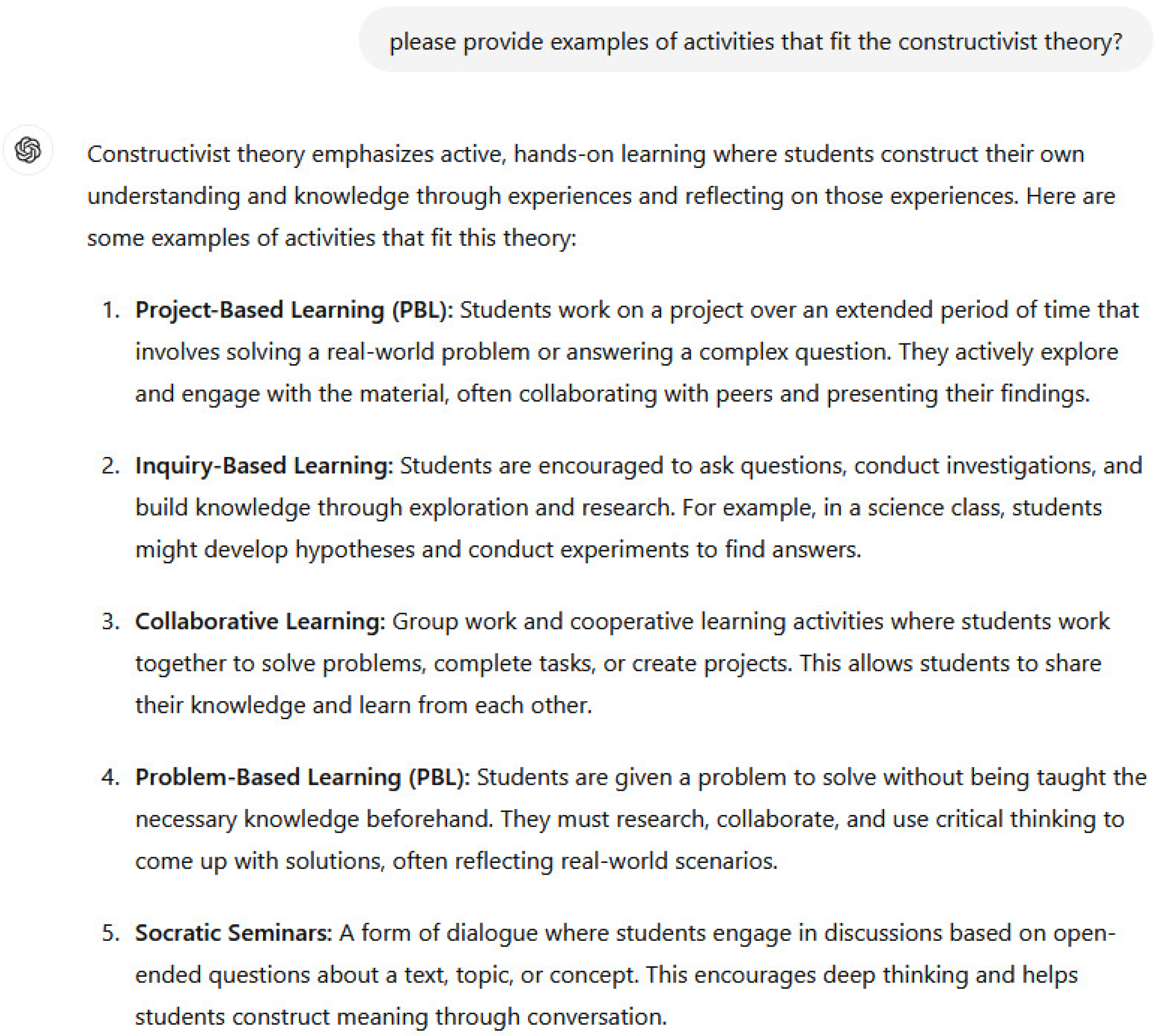

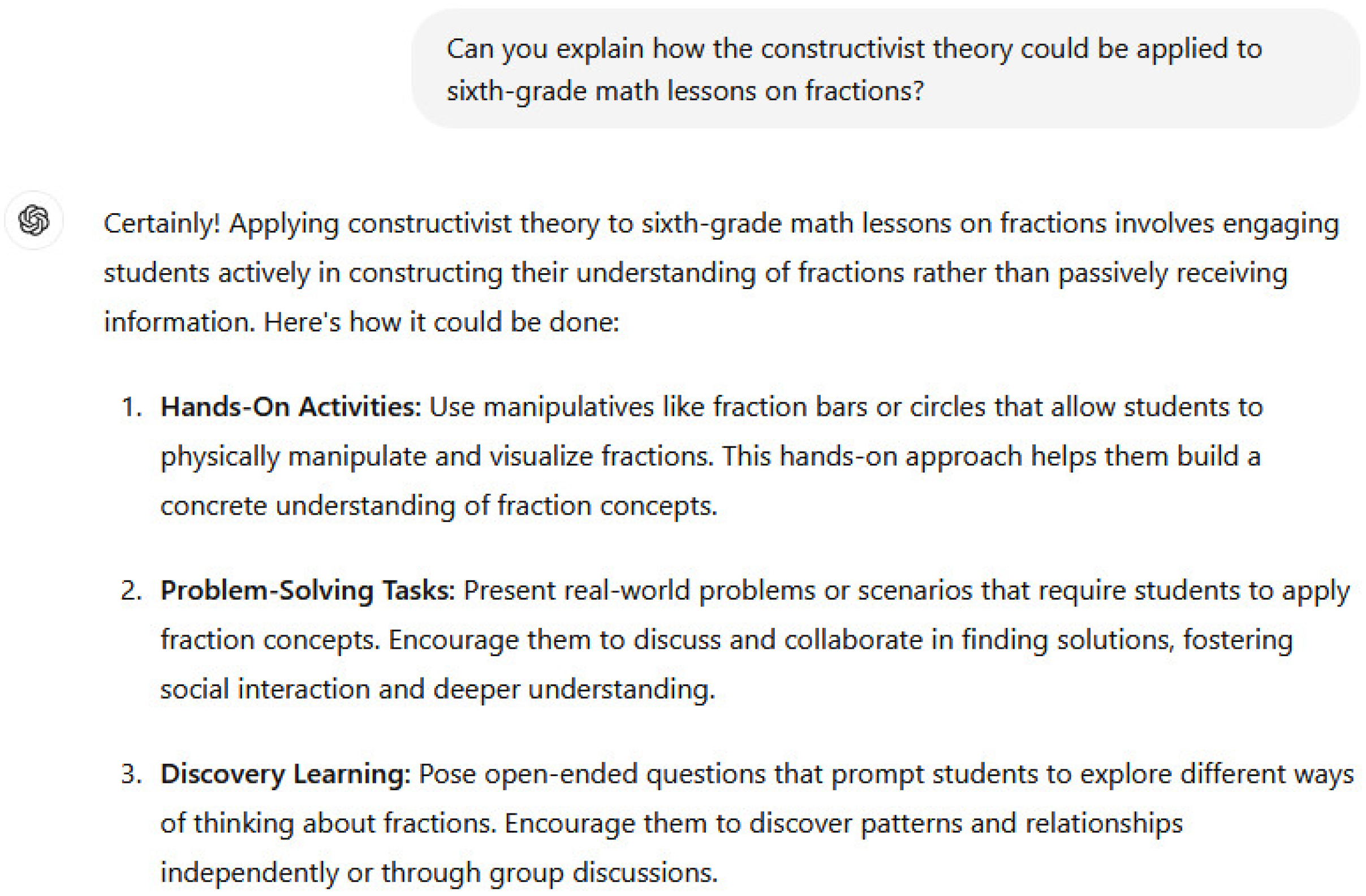

4.1.2. Applying Theory

We asked the chat for examples of activities that fit the constructivist theory as we wanted to understand how the theory could be applied in our learning environment (Interview 10).

Through the examples [the chatbot provided], I felt that I better understood constructivism and how to design teaching and learning according to constructivist ideas (Interview 1).

Examples of constructivist curriculum planning that is essentially and directly related to my needs and goals clarified for me how to be a constructivist teacher (Reflection 38).

In my practicum I observed my teacher mentor encouraging her students to work together or to research a subject, but I did not know that this was related to constructivism until I read the chatbot’s examples of activities (Reflection 24).

Through ChatGPT, we could check if our activities reflected constructivism. It was like having a personal tutor who ensured my teaching methods are aligned with this theory (Reflection 8).

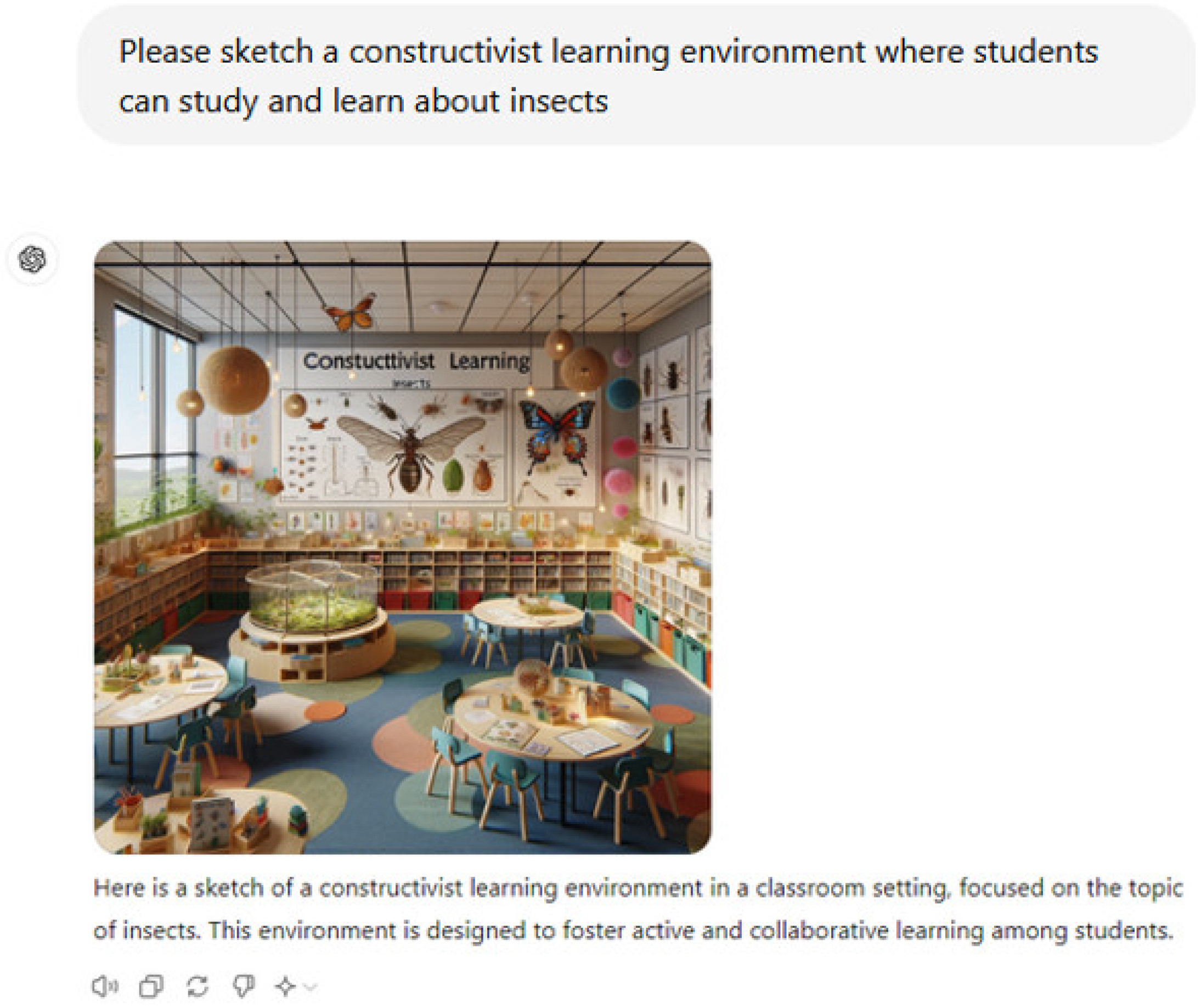

4.1.3. Visualizing Theory

The image helped me to better understand constructivist concepts by demonstrating how to create a setting that fosters active learning and collaboration (Reflection 41).

4.1.4. Translation Mechanisms: Iteration, Language Precision, and Critical Thinking

Ultimately, ChatGPT helped me understand the material more clearly because I could keep asking the chatbot to explain it over and over again, until I felt that I understood the theory (Reflection 26).

It took a lot of time to refine prompts, but when we came up with a fairly precise one, we got amazing results (Interview 2).

When we were not precise in conveying what we wanted, the responses were not always what we were looking for. It was frustrating to get irrelevant answers over and over again (Reflection 19).

As we did not receive the responses we wanted, we asked the chatbot to help us refine our prompts (Reflection 25).

We asked the chatbot to create a constructivist learning environment for our topic. However, the results weren’t good enough, so we started using more constructivist terms in our prompts and gave the chatbot negative feedback when the image didn’t correspond (Reflection 40).

4.2. Part 2: Incorporating ChatGPT-4 into Curriculum Planning

Planning lessons take a long time and can be frustrating sometimes. I feel like ChatGPT is like having a teaching assistant. It doesn’t always give me the perfect answer, but it helps me brainstorm ideas and organize my thoughts. (Reflection 3)

4.2.1. Objectives: Enhancing Personalization and Saving Time

I felt that the [ChatGPT] responses were technical and didn’t capture important emotional and social aspects, as would a real teacher (Interview 9).

The chat cannot create an optimal curriculum because it doesn’t know the students as I do (Reflection 5).

We asked the ChatGPT to help us formulate the goals for our learning environment. Time and again we got responses describing very general goals (Reflection 16).

I found it very helpful that the chat suggested activities suitable for students with different academic levels and different motivations (Reflection 3).

ChatGPT saves a lot of the teacher’s valuable time, and so enables the teacher to devote more time to answering questions and addressing needs of individual students (Interview 4).

ChatGPT supports independent learning and provides responses to my unique needs. So actually, I think that we experienced learning in a constructivist way by interacting with the chatbot (Reflection 15).

ChatGPT can be adapted to variety of learning styles and could be useful to a wide range of students with different verbal and visual needs (Reflection 27).

4.2.2. Content: Organization, Articulation, and Reliability

ChatGPT can organize large amounts of content into summary tables and other different formats, according to my needs. I’m not sure I could have managed to do this on my own (Interview 2).

Through ChatGPT, I was exposed to a level of knowledge beyond what I had learned in my studies and certainly beyond what I had known before (Reflection 34).

The chatbot helped me to write down my thoughts and ideas more accurately, to express myself better, and thus to present a better plan (Reflection 19).

I feel that I do not know enough about AI to teach my students about it (Reflection 8).

I’m not sure if the information I got from the chat is accurate or not, and it makes it hard for me to trust it (Reflection 23).

The chat provided me with information that contradicts what I had learned in my courses, and this made me question its reliability (Reflection 41).

These reliability concerns may reflect the tension between the convenience of using GAI tools in CP and the responsibility of PSTs to ensure the accuracy and appropriateness of the content they use in their teaching. Such hesitations may also reflect PSTs’ awareness of the limitations of GAI-based CP, as well as their role in critically assessing and verifying the information provided by GAI tools.I am worried that, on many occasions, I fully relied on the chatbot’s answers and did not verify the information (Reflection 9).

The learning processes will be less effective if we do not teach our students to critically assess the information and content they receive from the chat (Reflection 37).

4.2.3. Activities: Inspiration, Ideas, and Creativity Catalysis

There is something enjoyable for a teacher in getting inspiration from the chat and then developing the ideas independently (Reflection 36).

By generating materials ChatGPT gave me more time to use my imagination and think more creatively about activities (Interview 7).

CP, in my view, reflects the teacher’s character. Every teacher conveys to the students their unique attitude, and if we all prepare the same assignments and lessons, we will lose our creativity (Reflection 12).

I felt that the chat was making me less creative. Instead of improving my mind and coming up with my own ideas, I got an immediate solution, and I didn’t feel that I was using my own creativity (Interview 5).

4.2.4. Assessment: Feedback

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agyapong, B., Obuobi-Donkor, G., Burback, L., & Wei, Y. (2022). Stress, burnout, anxiety and depression among teachers: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktan, S. (2021). Waking up to the dawn of a new era: Reconceptualization of curriculum post COVID-19. Prospects, 51, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annapureddy, R., Fornaroli, A., & Gatica-Perez, D. (2024). Generative AI literacy: Twelve defining competencies. Digital Government: Research and Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Baytak, A. (2024). The content analysis of the lesson plans created by ChatGPT and Google Gemini. Research in Social Sciences and Technology, 9(1), 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biberman-Shalev, L., Pinku, G., Hemi, A., Nativ, Y., Paz, O., & Enav, Y. (2024). Portion coherence: Enhancing the relevance of introductory courses in teacher education. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1415518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbitt, J. F. (1918). The curriculum. Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Thematic analysis. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in health social sciences (pp. 843–860). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Cahapay, M. B. (2020). Rethinking education in the new normal post COVID-19 era: A curriculum studies perspective. Aquademia, 4(2), ep20018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carcary, M. (2009). The research audit trial—Enhancing trustworthiness in qualitative inquiry. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 7, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cevikbas, M., König, J., & Rothland, M. (2023). Empirical research on teacher competence in mathematics lesson planning: Recent developments. ZDM–Mathematics Education, 56, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C. K. Y. (2023). Is AI changing the rules of academic misconduct? An in-depth look at students’ perceptions of ‘AI-giarism’. arXiv, arXiv:2306.03358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran-Smith, M. (2000). The future of teacher education: Framing the questions that matter. Teaching Education, 11(1), 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, L. S., Smagorinsky, P., Fry, P. G., Konopak, B., & Moore, C. (2002). Problems in developing a constructivist approach to teaching: One teacher’s transition from teacher preparation to teaching. The Elementary School Journal, 102(5), 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G. (2023). Examining science education in ChatGPT: An exploratory study of generative artificial intelligence. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 32, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J., Cowling, M., & Allen, K. (2023). Leadership is needed for ethical ChatGPT: Character, assessment, and learning using artificial intelligence (AI). Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 20(3), 02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z. (2004). The role of theory in teacher preparation: An analysis of the concept of theory application. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 32(2), 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolezal, D., Motschnig, R., & Ambros, R. (2025). Pre-service teachers’ digital competence: A call for action. Education Sciences, 15(2), 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, C. V. (2020). The role of the teacher and AI in education. In International perspectives on the role of technology in humanizing higher education (pp. 33–48). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. (2004). Design and process in qualitative research. In U. Flick, E. von Kardoff, & I. Steinke (Eds.), A companion to qualitative research (pp. 146–152). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, M. A. (2016). Teacher education curriculum. In J. Loughran, & M. L. Hamilton (Eds.), International handbook of teacher education (pp. 187–230). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, P., Raturi, S., & Venkateswarlu, P. (2023). ChatGPT for designing course outlines: A boon or bane to modern technology. Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurl, T. J., Markinson, M. P., & Artzt, A. F. (2024). Using ChatGPT as a lesson planning assistant with preservice secondary mathematics teachers. Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, R., Ali, N., El Zein, F., Fidalgo, P., & Khurma, O. A. (2024). AI to the rescue: Exploring the potential of ChatGPT as a teacher ally for workload relief and burnout prevention. Research & Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 19, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauhiainen, J. S., & Guerra, A. G. (2023). Generative AI and ChatGPT in school children’s education: Evidence from a school lesson. Sustainability, 15(18), 14025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarez, B. (2019). The intersection of theory and practice in teacher preparation courses. Journal of Instructional Research, 8(2), 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, M. R. (2024). Are lesson plans created by ChatGPT more effective? An experimental study. International Journal of Technology in Education, 7(1), 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korthagen, F. A., & Kessels, J. P. (1999). Linking theory and practice: Changing the pedagogy of teacher education. Educational Researcher, 28(4), 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahenbuhl, K. S. (2016). Student-centered education and constructivism: Challenges, concerns, and clarity for teachers. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 89(3), 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, L. R. (2004). Constructing constructivism: How student-teachers construct ideas of development, knowledge, learning, and teaching. Teachers and Teaching, 10(2), 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G. G., & Zhai, X. (2024). Using ChatGPT for science learning: A study on pre-service teachers’ lesson planning. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 17, 1683–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W., Son, J. W., & Kim, D. J. (2018). Understanding preservice teacher skills to construct lesson plans. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 16, 519–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, A. (2008). Introductory essay. In F. M. Connelly (Ed.), Curriculum and instruction (pp. 145–151). Sage Publication Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, D. L. (2004). The significance of students: Can increasing “student voice” in schools lead to gains in youth development? Teachers College Record, 106, 651–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, T., & Nolan, A. (2020). Teacher agency and professional practice. Teachers and Teaching, 26(1), 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M., Rauschenberger, M., & Schön, E. M. (2023, May 16). We need to talk about ChatGPT: The future of AI and higher education. 2023 IEEE/ACM 5th International Workshop on Software Engineering Education for the Next Generation (SEENG) (pp. 29–32), Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. (2023). ChatGPT: Optimizing language models for dialogue. Available online: https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt/ (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Pinar, W. F. (2004). What is curriculum theory? Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Polak, S., Schiavo, G., & Zancanaro, M. (2022, April 29–May 5). Teachers’ perspective on artificial intelligence education: An initial investigation. CHI Conference on human factors in computing systems extended abstracts (pp. 1–7), New Orleans, LA, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, M. (2000). Using phenomenographic research methodology in the context of research in teaching and learning. In J. A. Bowden, & E. Walsh (Eds.), Phenomenography (pp. 34–46). RMIT University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, Y., Cheng, X., He, Y., Zeng, A., & Mou, J. (2025). Misfortune or blessing? The effects of GAI misinformation on human-GAI collaboration. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10125/108851 (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Schwab, J. J. (2013). The practical: A language for curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 45(5), 591–621, (Original work published 1969). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L. S. (1998). Theory, practice, and the education of professionals. The Elementary School Journal, 98(5), 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelecki, A. (2023). To use or not to use ChatGPT in higher education? A study of students’ acceptance and use of technology. Interactive Learning Environments, 32, 5142–5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trust, T., Whalen, J., & Mouza, C. (2023). Editorial: ChatGPT: Challenges, opportunities, and implications for teacher education. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 23(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, R. W. (1949). Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2023). International task force on teachers for education 2030. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg, G., & du Plessis, E. (2023). ChatGPT and generative AI: Possibilities for its contribution to lesson planning, critical thinking, and openness in teacher education. Education Sciences, 13(10), 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Manen, M. (1977). Linking ways of knowing with ways of being practical. Curriculum Inquiry, 6(3), 205–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazhayil, A., Shetty, R., Bhavani, R. R., & Akshay, N. (2019, December 9–11). Focusing on teacher education to introduce AI in schools: Perspectives and illustrative findings [Conference session]. 2019 IEEE Tenth International Conference on Technology for Education (pp. 71–77), Goa, India. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Li, L., Tan, S. C., Yang, L., & Lei, J. (2023). Preparing for AI-enhanced education: Conceptualizing and empirically examining teachers’ AI readiness. Computers in Human Behavior, 146, 107798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wursta, M., Brown-DuPaul, J., & Segatti, L. (2004). Teacher education: Linking theory to practice through digital technology. Community College Journal of Research & Practice, 28(10), 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X. (2023). ChatGPT for next generation science learning. XRDS: Crossroads, The ACM Magazine for Students, 29(3), 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., & Watterston, J. (2021). The changes we need: Education post COVID-19. Journal of Educational Change, 22, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Biberman-Shalev, L. Prompting Theory into Practice: Utilizing ChatGPT-4 in a Curriculum Planning Course. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020196

Biberman-Shalev L. Prompting Theory into Practice: Utilizing ChatGPT-4 in a Curriculum Planning Course. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(2):196. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020196

Chicago/Turabian StyleBiberman-Shalev, Liat. 2025. "Prompting Theory into Practice: Utilizing ChatGPT-4 in a Curriculum Planning Course" Education Sciences 15, no. 2: 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020196

APA StyleBiberman-Shalev, L. (2025). Prompting Theory into Practice: Utilizing ChatGPT-4 in a Curriculum Planning Course. Education Sciences, 15(2), 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020196