From Framework to Practice: A Study of Positive Behaviour Supports Implementation in Swedish Compulsory Schools

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Purpose and Research Questions

- -

- RQ 1. What is the prevalence and nature of PBS principles as implemented in two Swedish classrooms?

- -

- RQ 2. How do staff perceive PBS implementation and its reported benefits and challenges?

- -

- RQ 3. How does classroom PBS implementation align with staff perceptions and experiences?

3. What Is the PBS Framework, and Why Is It Relevant?

3.1. What the PBS Framework

3.2. Relevance to the Study (Why PBS?)

4. Previous Research

5. Theoretical Framework

6. Methodology

6.1. Design

6.1.1. Data Collections

6.1.2. Data Analysis

7. Ethical Considerations

8. Results

8.1. Classroom Observations

8.1.1. The Quantitative Analysis of Observations

- Teaching Materials: Books were the most commonly used teaching aids, used in 13 of 26 lessons. In contrast, digital tools like smartboards and projectors, although available in all classrooms, were used in only five lessons. While descriptive, this provides context on the prevailing pedagogical environment, suggesting a reliance on traditional methods that may impact the adoption of technology-supported PBS strategies.

- Lesson Structure: All 26 lessons had a clear and predictable structure, with a distinct beginning, clear goals, and a conclusion. Instructions were particularly clear in 6 of the 26 lessons, enabling students to follow expectations with minimal prompting from the teacher.

8.1.2. Thematic Analysis of the Observations

The Proactive and Consistent Teacher

The Balance Between Tradition and Innovation

Pathways to Behavioural Integration

8.2. Interview Data

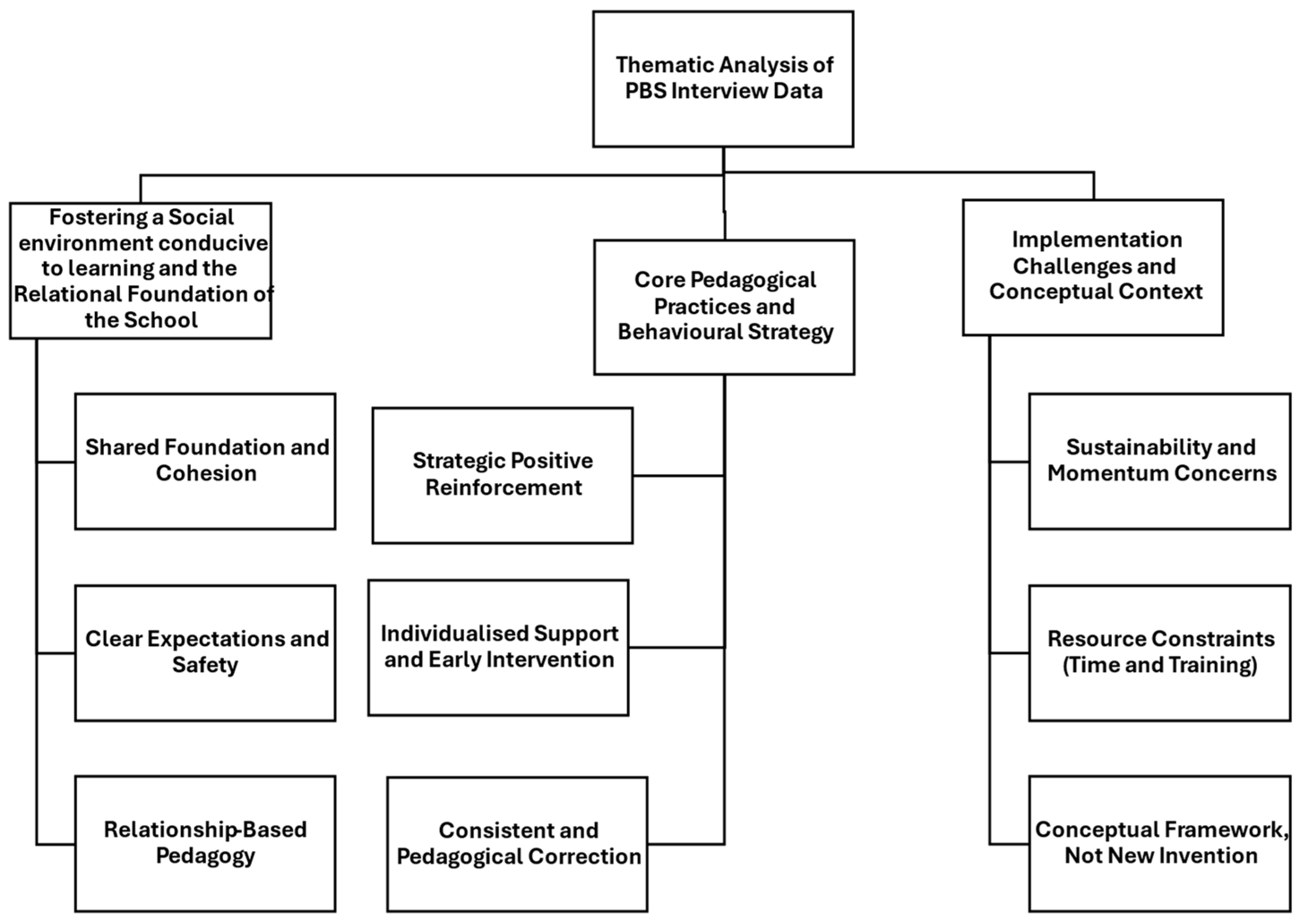

8.2.1. Thematic Analysis of Interview Data

8.2.2. Quantitative Summarization of Interview Results

8.3. Triangulated Results

8.3.1. Congruence Between Observed and Reported Data (Identifying Generative Mechanisms)

8.3.2. Divergence Between Observed and Reported Data (Identifying Counter-Mechanisms)

9. Discussion

- The Power of Triangulation: Unmasking the Proactive–Reactive Gap

- The study’s use of methodological triangulation, combining direct observation and teacher interviews, successfully addresses a common methodological gap in implementation research (Noble & Heale, 2019). By moving beyond self-reported data, the research provides a more nuanced understanding of PBS effectiveness. The most significant finding from this approach is the divergence between teachers’ reported beliefs (Actual domain) and their observed behaviours (Empirical domain). While teachers articulated a strong belief in the necessity of a positive, proactive approach and building a “bank of positive interactions,” observations revealed that corrective, negative statements occurred more frequently than positive reinforcements. This contradiction establishes the phenomenon that the rest of the discussion analyzes.

- Understanding the disparity through Critical Realism

- The PBS framework itself acts as a generative mechanism intended to produce proactive teaching practices. Where the framework succeeded (Realization), it created the Actual event of a calm school climate. Where it failed (Divergence), the Real mechanism of deeply established, reactive habit was allowed to dominate Empirical observation. The challenge for professional development, therefore, is not to simply introduce the framework (which has been done) but to target and override the Real mechanism of reactive habit.

- Structural Barriers to Full Integration

- The Work-in-Progress Paradigm

- Methodological Limitations and Future Research

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PBS | Positive Behaviour Supports |

| CW-FIT | Class-Wide Function-Related Intervention Teams |

| CR | Critical realism |

Appendix A

| Question | Summary of Observation |

|---|---|

| What teaching materials are used? Do all students have the same teaching materials? | In all, 13 use books by both teachers and students, 5 computers and smartboards or projectors, 2 blackboards, 2 cards and pictures, 1 audiobook, 2 notebooks and paper. |

| Does the lesson have a clear structure? | All 26 have a clear structure. Five have a very good structure and the students feel secure in what needs to be done. |

| Do the students understand what is expected of them? | In all 26, the students understand what is expected of them. In 2 of 26, they need to raise their hand. In 6 of 26, the instructions are very clear. In 1, the teacher reminds them often. |

| Are expectations written in observable, measurable, positively stated, clearly defined terms and are they well visible? | In 4, they are not in the classroom. In 2, they are behind students. In 9, they are on the door. Yes, in all 26, the signs in the school are the same and are adapted for age and area. |

| Are the routines adapted to the expectations? | Yes, all the signs in the school are the same and are age and area-appropriate. |

| Does the teacher seem calm and consistent in delivering corrections? How? | The teachers are calm in all lessons but some are more so. |

| Is the classroom furniture organized so that students are visible all the time and the teacher has easy access to all students, and do the students have the opportunity to collaborate? | The furniture in the classroom is well arranged in all classes. |

| Are there separate spaces for students to self-regulate and/or work independently? | No separate spaces exist in 11 of 26. Some teachers do not use them. |

| Does the teacher often interact with students and provide positive feedback, correction, and error correction? | Almost all teachers give feedback, corrections, and error corrections, mostly through encouragement and saying “yes, good…”. |

| Are there opportunities for the student/class to show their knowledge of the desired behavior? | Yes, in all lessons, by the students answering questions, following instructions. |

| Is the educator actively engaged in supervision in the classroom (i.e., moving, scanning, interacting)? | Yes, teachers are actively engaged in classroom supervision, mostly by moving and scanning. |

| Did the teacher provide students with opportunities to respond and participate? | Yes, all teachers provide students with opportunities to respond and participate: 5 give them time, 4 ensure everyone gets to participate. |

| Does the teacher give effective praise to acknowledge appropriate academic and social behavior? | All teachers give praise, more so to students who answer or do things correctly. |

| Are social skills intentionally taught and modeled in the classroom (e.g., self-regulation, self-awareness, communication, healthy coping strategies, problem-solving, etc.)? | In all, 4 of 26 do not teach social skills in the classroom. Most do so by reminding them of expectations. Four also say “wait your turn to talk…”. |

| Does the teacher integrate behavior and life skill examples from related initiatives (self-regulation skills, bullying prevention skills, coping skills, etc.)? | In all, 13 of 26 do not integrate behavior and life skills. Four do so within Self-regulation. Six do so by reminding them of expectations, mostly when a situation arises. (Perhaps this depends on their subject?) |

| Do the students’ views on the rules matter? Are they clear? Are they meaningful to the students? | In 7 of 26, the students cannot always see the rules because they are either not there or are behind students. |

| Are the classroom expectations the same as school-wide expectations? | The expectations are clear in all lessons and are meaningful. All the signs that exist are adapted for the age and area. The same signs for children and the same for teenagers are adapted in all classes. |

| Does the teacher maximize the simultaneous participation of all students through strategies and questions to get group answers? | In all, 19 of 26 teachers maximize students to get group answers. Three do it sometimes or in certain parts of the lesson. Four have art or woodcraft and the students work alone. |

| Does the teacher give specific feedback and motivate the students? | Only 1 does not give specific feedback to students. Most do it through praise. |

| Does the teacher use different strategies to respond to inappropriate behavior (e.g., planned ignoring, prompting, re-teaching, etc.)? | In all, 8 respond to inappropriate behavior by looking at the student, saying the student’s name, talking to the student, or “shh shh SH”. Three do it through ignoring. Two do it preventively by giving instructions and explanations. |

| Does the teacher give corrective feedback? | In all, 8 of 26 teachers do not give proper corrective feedback. Five do it when students fail or cannot answer correctly by rephrasing the question or using other words. Two do it when the student exhibits the correct behavior. One does it by reminding them of expectations. |

| Finding Category | Quantitative Data (N = 26) | Qualitative Theme |

|---|---|---|

| Lesson Structure | All 26 lessons had a clear, predictable structure (start, goals, conclusion). Five lessons had an exceptionally effective structure that reduced disruptive behavior. | The Proactive and Consistent Teacher—Teachers skillfully established a predictable environment, fostering student security and focus. |

| Teaching Materials | Books were the main resource in 13 lessons (50%). Digital tools (smartboards, projectors) were only used in 5 of 19 relevant subjects (19%). Paper and notebooks were primary in 2 lessons, while whiteboards and pictures/cards were each primary in 2 lessons. | The Balance Between Tradition and Innovation—A reliance on traditional methods (books, paper) was observed, despite the availability of modern technology. |

| Rules & Expectations | Rules were visible in 19 classrooms (73%), but in 7 lessons (27%) they were not consistently visible to all students. All 26 lessons had clear, age-appropriate rules. In 6 lessons, instructions were so clear that students needed minimal teacher prompting. | The Proactive and Consistent Teacher—Teachers effectively communicated expectations, but the physical reinforcement (visible rules) was not always optimal. |

| Teacher–Student Interaction | Teachers were consistently calm and active, moving around the classroom in all 26 lessons. Praise and positive feedback were given in 25 lessons (96%). All students had opportunities to participate. | The Proactive and Consistent Teacher—Teachers demonstrated strong relational and managerial skills, actively engaging with students and providing positive reinforcement. |

| Behavioral Integration | Social skills were integrated into 22 lessons (85%). Life skills were integrated into 13 lessons (50%). Only 4 teachers explicitly taught social skills. | Pathways to Behavioral Integration—While teachers were good at correcting behavior, the proactive, explicit teaching and integration of social and life skills were less frequent. |

| Behavioral Correction | Inappropriate behavior was corrected in 18 lessons (69%). However, in 8 lessons (31%), corrective feedback was not provided. In 5 lessons, teachers used rephrasing to correct academic errors. | Pathways to Behavioral Integration—The response to misbehavior was inconsistent; a significant portion of observations lacked clear corrective feedback. |

| Classroom Environment | All classrooms had good furniture arrangements that allowed for teacher access and student collaboration. In 11 lessons (42%), separate spaces for independent work/self-regulation were not available or used. | The Proactive and Consistent Teacher—The physical layout generally supported teacher supervision and peer collaboration, but opportunities for independent work and self-regulation were often overlooked. |

References

- Abou Zaid, F. (2024). Staff and student perspectives and effects of positive behaviour support: A literature review. Educational Psychology in Practice, 40(2), 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algozzine, K., & Algozzine, B. (2007). Classroom instructional ecology and school-wide positive behavior support. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 24(1), 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allmark, P., Boote, J., Chambers, E., Clarke, A., McDonnell, A., Thompson, A., & Tod, A. M. (2009). Ethical issues in the use of in-depth interviews: Literature review and discussion. Research Ethics, 5(2), 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, K. E. C., Lundgren, J. S., & Bernhardsson, S. (2024). Facilitators and barriers for implementing the PALS school-wide positive behavior support model in a Swedish municipality: A focus group study. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 65(5), 919–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, R. (1979). The possibility of naturalism: A philosophical critique of the contemporary human sciences. Harvester Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar, R. (2008). A realist theory of science (New ed.). Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Bohanon, H., Fenning, P., Carney, K. L., Minnis-Kim, M. J., Anderson-Harriss, S., Moroz, K. B., Hicks, K. J., Kasper, B. B., Culos, C., Sailor, W., & Pigott, T. D. (2006). Schoolwide application of positive behavior support in an urban high school: A case study. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 8(3), 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahu, P. M. M., & Quota, M. B. N. (2019). Does school safety and classroom disciplinary climate hinder learning? Evidence from the MENA region. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Caldarella, P., Williams, L., Hansen, B. D., & Wills, H. P. (2015). Managing student behavior with class-wide function-related intervention teams: An observational study in early elementary classrooms. Early Childhood Education Journal, 43(3), 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C. R., Grady, E. A., Long, A. C., Renshaw, T., Codding, R. S., Fiat, A., & Larson, M. (2017). Evaluating the impact of increasing general education teachers’ ratio of positive-to-negative interactions on students’ classroom behavior. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 19(2), 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowski, A., Hsien, M., Van Der Zant, T., & Ahmed, S. K. (2025). “We are left to fend for ourselves”: Understanding why teachers struggle to support students’ mental health. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1505077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danermark, B., Ekström, M., Jakobsen, L., & Karlsson, J. C. (2019). Explaining society: Critical realism in the social sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dwarika, V. M. (2019). Positive behaviour support in South African foundation phase classrooms: Teacher reflections. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 9(1), e1–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R., Lohrmann, S., Irvin, L. K., Kincaid, D., Vossler, V., & Ferro, J. (2009). Systems change and the complementary roles of in-service and preservice training in schoolwide positive behavior support. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemin, M., & Heggen, K. (2012). The narrative approach as a learning strategy in the formation of novice researchers. Qualitative Health Research, 22(5), 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, R. H., Dunlap, G., & Sugai, G. (2025). Science, values, systems, and data: The historical foundations of PBS and PBIS. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, R. H., & Sugai, G. (2015). School-wide PBIS: An example of applied behavior analysis implemented at a scale of social importance. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 8(1), 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klette, K. (2023). Classroom observation as a means of understanding teaching quality: Towards a shared language of teaching? Journal of Curriculum Studies, 55(1), 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuvvetli, R., Kuvvetli, M., & KAZU, İ. Y. (2023). The power of positive school climate: A review of its impact on student outcomes and teacher well-being. ResearchGate. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369528855_THE_POWER_OF_POSITIVE_SCHOOL_CLIMATE_A_REVIEW_OF_ITS_IMPACT_ON_STUDENT_OUTCOMES_AND_TEACHER_WELL-BEING (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Lau, L. H. S., Moore, D. W., & Anderson, A. (2019). Behavior support strategies in Singapore preschools: Practices and outcomes. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 21(4), 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Loughland, T. (2019). Classroom observation as method for research and improvement. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, H., & Heale, R. (2019). Triangulation in research, with examples. Evidence Based Nursing, 22(3), 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. (2024). PISA 2022 results: Volume II: Learning during—And from—Disruption. OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/pisa-2022-results-volume-ii_a97db61c-en (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Oliver, R. M., Lambert, M. C., & Mason, W. A. (2019). A pilot study for improving classroom systems within schoolwide positive behavior support. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 27(1), 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver-Hoyo, M., & Allen, D. (2006). The use of triangulation methods in qualitative educational research. Journal of College Science Teaching, 35(4), 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Reinke, W. M., Herman, K. C., & Stormont, M. (2013). Classroom-level positive behavior supports in schools implementing sw-pbis: Identifying areas for enhancement. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 15(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusby, J. C., Crowley, R., Sprague, J., & Biglan, A. (2011). Observations of the middle school environment: The context for student behavior beyond the classroom. Psychology in the Schools, 48(4), 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailor, W., Dunlap, G., Sugai, G., & Horner, R. H. (Eds.). (2009). Handbook of positive behavior support. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Skolinspektionen. (2024). Garantin för tidiga stödinsatser ger inte fler elever stöd. Skolinspektionen. Available online: https://www.skolinspektionen.se/aktuellt/nyheter/garantin-for-tidiga-stodinsatser-ger-inte-fler-elever-stod/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Skolverket. (2025). Attityder till skolan. Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/statistik-och-utvarderingar/uppfoljning-och-utvardering/attityder-till-skolan (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Sugai, G., & Horner, R. H. (2006). A promising approach for expanding and sustaining school-wide positive behavior support. School Psychology Review, 35(2), 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugai, G., Horner, R. H., Dunlap, G., Hieneman, M., Nelson, C. M., Scott, T., Liaupsin, C., Sailor, W., Turnbull, A. P., Turnbull, H. R., III, Wickham, D., Wilcox, B., & Ruef, M. (2000). Applying positive behavior support and functional behavioral assessment in schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 2(3), 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Camp, A. M., Wehby, J. H., Copeland, B. A., & Bruhn, A. L. (2021). Building from the bottom up: The importance of tier 1 supports in the context of tier 2 interventions. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 23(1), 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welton-Mitchell, C., Schwatka, N. V., Dally, M., Levine, S., & Lopez, I. (2025). Mental health integrated emergency preparedness for the public school workforce. Journal of School Violence, 24(3), 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, H. P., Iwaszuk, W. M., Kamps, D., & Shumate, E. (2014). CW-FIT: Group contingency effects across the day. Education and Treatment of Children, 37(2), 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wragg, E. C. (1999). An introduction to classroom observation (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

| Category | School 1 | School 2 | Total (Both Schools) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observation Hours | 17 lessons (approx. 15 h) | 9 lessons (approx. 8 h) | 26 lessons (approx. 23 h) |

| Interviews | 10 interviews with 10 teachers | 3 interviews with 4 teachers | 13 interviews with 14 teachers |

| The total staff at the two schools | 16 teachers | 10 teachers | 26 teachers |

| Practice | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Lesson Structure | |

| Clear and predictable structure | 26/26 (100%) |

| Teaching Materials | |

| Books used by teachers and students | 13/26 (50%) |

| Digital tools (smart boards, projectors) used | 5/19 (26%) * |

| Rules and Expectations | |

| Rules are posted visibly in the classroom | 11/11 (100%) * |

| Expectations are clear and meaningful | 26/26 (100%) |

| Students could not always see the rules | 7/26 (27%) |

| Social Skills and Correction | |

| Social skills taught in class | 22/26 (85%) |

| Behavioural/life skills integrated | 13/26 (50%) |

| Corrective feedback was not given for inappropriate behavior | 8/26 (31%) |

| Category | Key Concept | Number of Participants Who Mentioned |

|---|---|---|

| Benefits | Calm/Calmer climate | 5 |

| Security | 4 | |

| Clear expectations/Structure | 6 | |

| Unity/Collaboration | 5 | |

| Positive work/School Climate | 4 | |

| Focus on Proactive/Positive Support | 3 | |

| Challenges | Lack of time | 3 |

| Difficulty with change | 1 | |

| Inconsistent interest | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abou Zaid, F.; Boström, L. From Framework to Practice: A Study of Positive Behaviour Supports Implementation in Swedish Compulsory Schools. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1621. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121621

Abou Zaid F, Boström L. From Framework to Practice: A Study of Positive Behaviour Supports Implementation in Swedish Compulsory Schools. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1621. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121621

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbou Zaid, Fathi, and Lena Boström. 2025. "From Framework to Practice: A Study of Positive Behaviour Supports Implementation in Swedish Compulsory Schools" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1621. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121621

APA StyleAbou Zaid, F., & Boström, L. (2025). From Framework to Practice: A Study of Positive Behaviour Supports Implementation in Swedish Compulsory Schools. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1621. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121621