Visualising the Fluidity of Multilingual and Intercultural Identities of Australian University Students Studying Abroad in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Visual Metaphor Approach

2.2. The Fluidity of Multilingual and Intercultural Identities

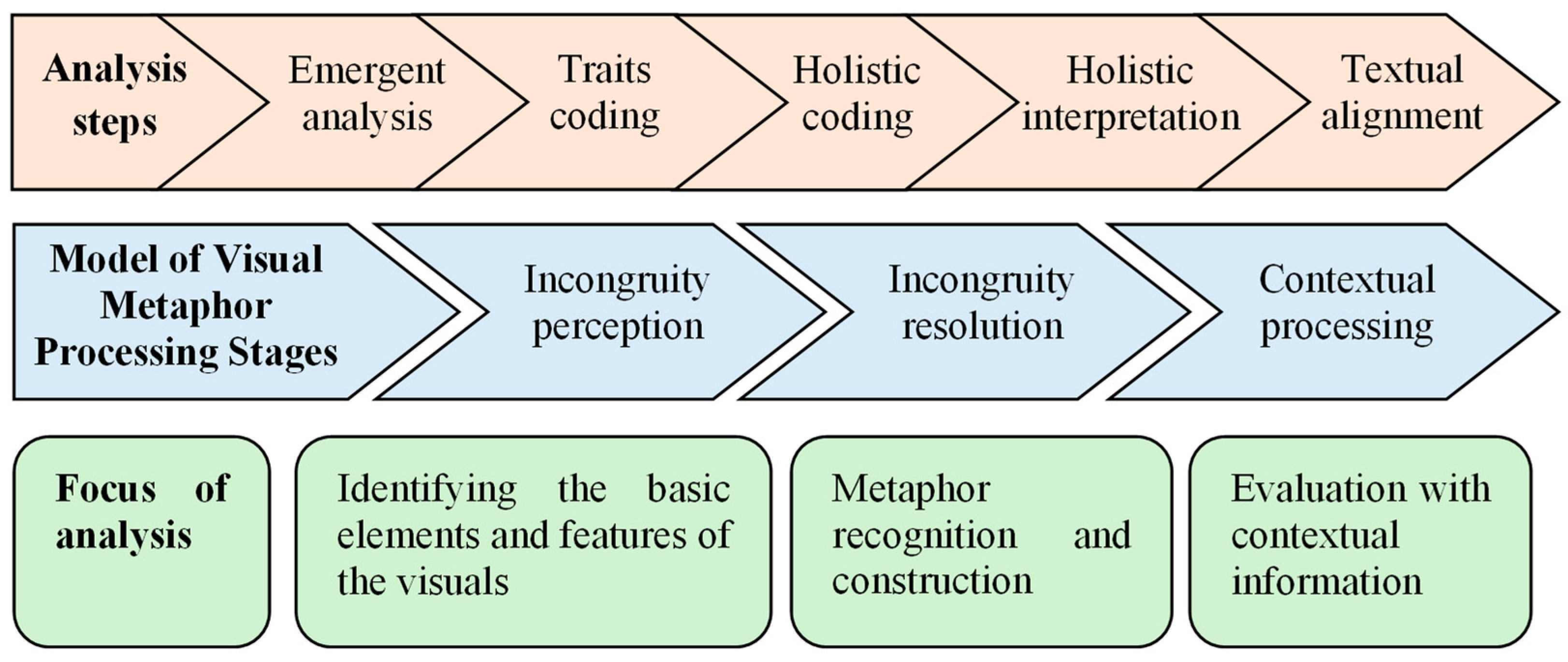

2.3. Operationalise Visual Metaphor as an Analytical Framework

- (a)

- Emergent analysis: This consists of a preliminary review of the drawings, cataloguing each individual element or characteristic depicted.

- (b)

- Traits coding: Identifying patterns or common traits among the depicted features within each drawing.

- (c)

- Holistic coding: Assessing the overall tone and style of the drawing, for instance, whether it appeared positive or negative, constructivist or passive, active or inactive.

- (d)

- Holistic interpretation: This deeper interpretative step involves asking broader questions, such as “What message does this drawing convey?”

- (e)

- Textual alignment: Exploring the alignment between textual and visual metaphors to understand their synergy.

- (a)

- Incongruity perception: This stage entails analysing basic visual elements like patterns, colours, and contrasts (perceptual analysis), integrating this sensory information with prior knowledge (implicit information integration), and classifying impressions formed in the earlier steps through labelling objects, scenes, and their traits (explicit classification).

- (b)

- Incongruity resolution: This stage includes conceptual mapping between elements of the source and target domains in the visual, as well as recognition and appreciation of the metaphor.

- (c)

- Contextual processing: This stage involves considering supplementary information that can aid in interpreting and conceptualising the visual metaphor. This additional information may come from the perceiver’s existing knowledge or from context accompanying the visual metaphor.

Q: How do students’ visual metaphors capture the fluid and evolving nature of multilingual and intercultural identities?

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Data Collection

- A visual representation of their multilingual identity.

- A visual representation of their intercultural identity.

- A visual representation depicting the changes they experienced in their identities through the SA program.

3.3. Data Analysis Procedures

- (a)

- Identifying the basic elements and features of the visuals. This step focused on making a list of the visual elements through emergent analysis and describing their traits. The researchers conceptualised the overall trait of a visual artefact based on the specific traits of each identified element. These steps correspond to the phases of emergent analysis and trait coding, during which researchers identified visual incongruities along with their traits and patterns, as well as to the initial stage of perceiving incongruities in the VMP model.

- (b)

- Metaphor recognition and construction. This step focused on uncovering the underlying meanings of the metaphorical visual elements. The researchers examined how languages, cultures, identities, and changes were metaphorically expressed. To understand the creators’ intentions behind the drawings, they evaluated the overall tone and style of the artefacts through holistic coding, emphasising how participants depicted the fluidity of their identities using diverse visual styles. Finally, the researchers summarised the overall message of each drawing through holistic interpretation. This corresponds to holistic coding and interpretation when researchers addressed these incongruities by examining the visuals’ underlying meanings, relationships, metaphors, and the creator’s intentions, aligning with the incongruity resolution stage of the VMP model. At this stage, both frameworks emphasise moving beyond individual elements to explore the relationships, coherence, and intended messages within the visual metaphor.

- (c)

- Checking contextual information. The researchers interpreted the metaphors using participants’ written descriptions and interview data. In this study, textual materials were used to provide context for interpreting visual metaphors, following the approach of Šorm and Steen (2013). This corresponds to textual alignment when researchers contextualised these visual metaphors within the written materials provided by students, reflecting the contextual processing stage of the VMP model.

4. Data Analysis

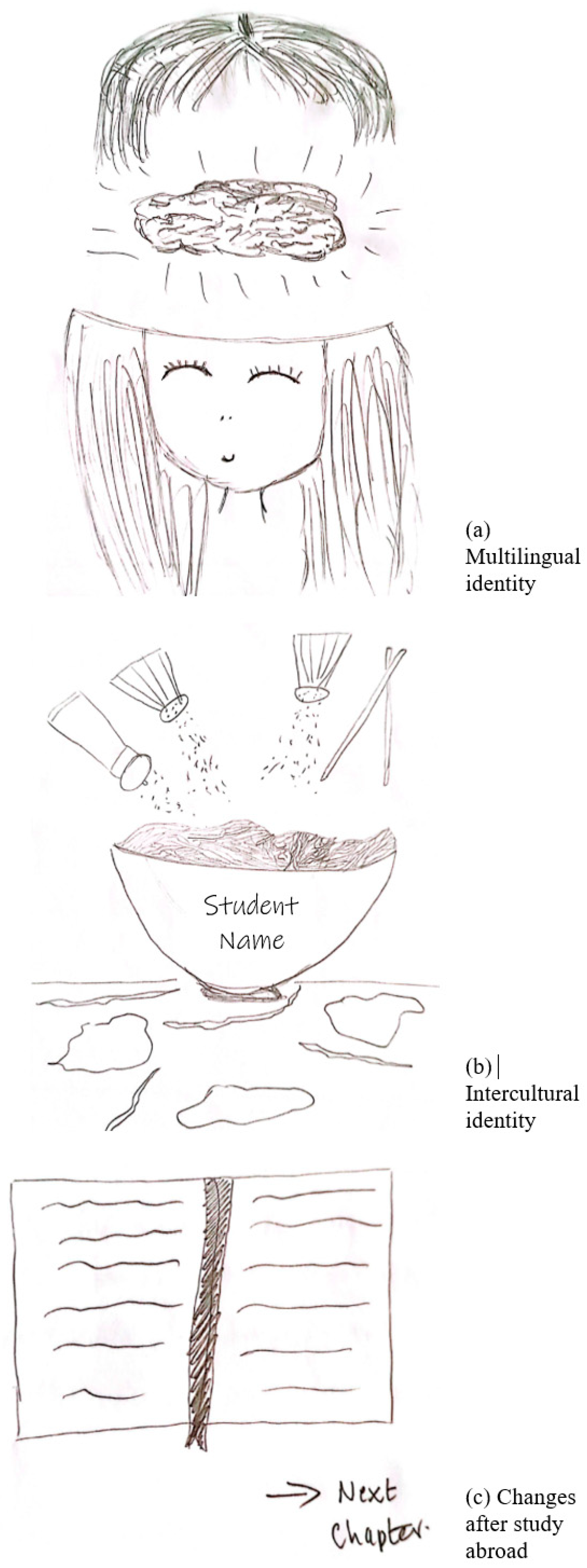

4.1. Annie: Continuous Evolution of Dynamic Identities

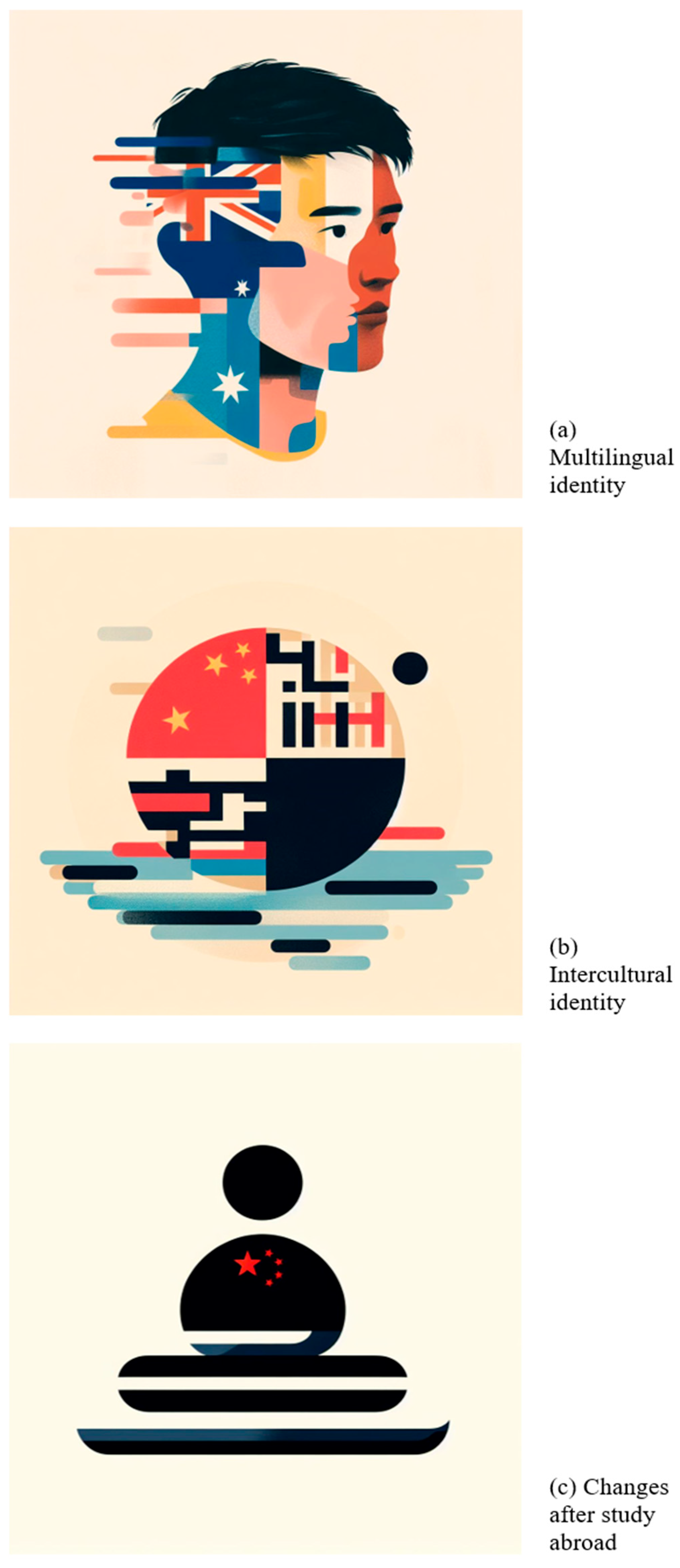

4.2. Jack: Blending of Heritage and Western Identities

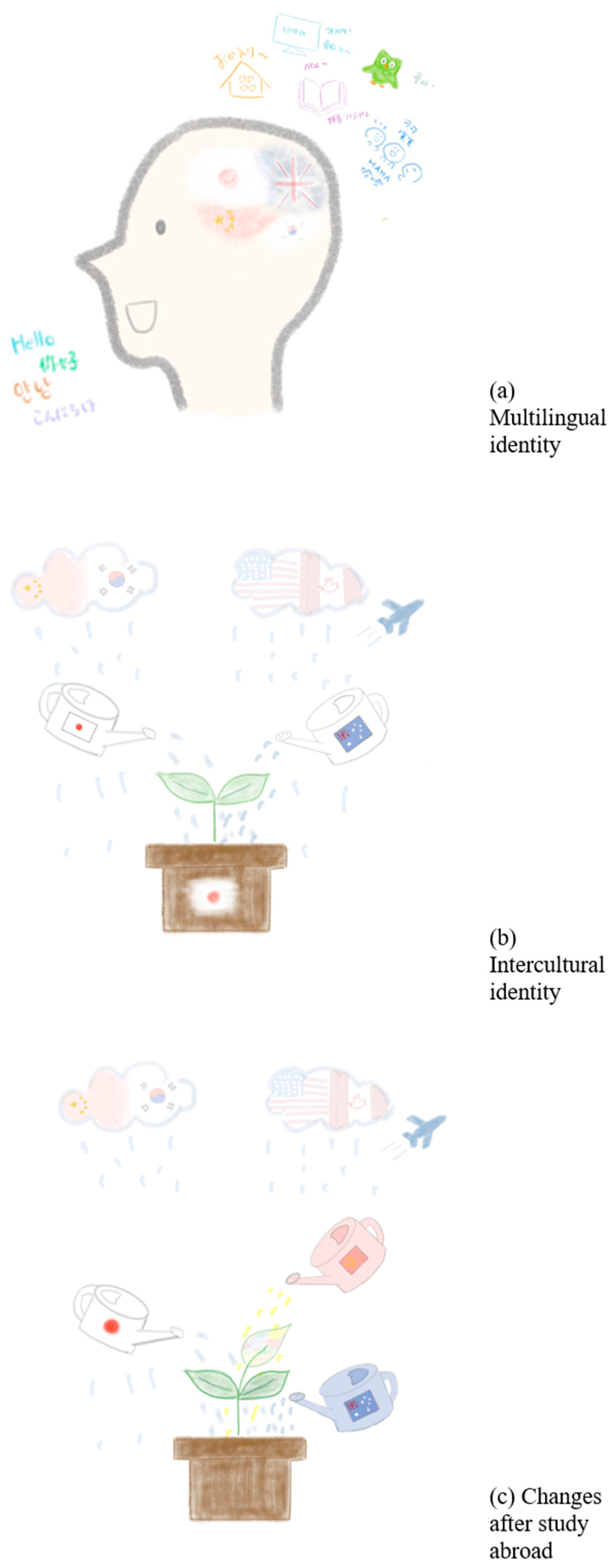

4.3. Hana: From National to Layered Intercultural Identities

5. Discussion

5.1. Embodying Fluidity in Visual Metaphor

5.2. Power and Limitations of Visual Methods for Future Studies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Visual Task Guide

- Begin by reflecting on your multilingual and intercultural experiences and how they shape your identity. Here are some questions that may help with your reflections (you do not need to answer these questions at this stage):

- How have your multilingual experiences before going to [the University] influenced your sense of self and identity?

- How have your intercultural experiences before going to [the University] influenced your sense of self and identity?

- How did you try to represent yourself as a multilingual speaker during your study at [the University] and/or in China?

- How did you represent yourself during intercultural communications at [the University] and/or in China?

- How do you feel about your multilingual identity at this moment?

- How do you feel about your intercultural identity at this moment?

- Can you identify any changes to your multilingual or intercultural identity since you participated in [the University’s] Intensive program?

- Create a self-portrait or visual representation that represents your multilingual and intercultural identity. You can choose to draw, paint, use symbols, signs, objects, animals, or a combination of these.

- Accompany your visual representation with a written description explaining the artwork and the symbolism behind your creative choices. You may use any language or a mix of languages that you feel comfortable with.

Appendix B. Detailed Analysis of Annie’s Drawings

| Model of Visual Metaphor Processing Stages | Incongruent Perception | Incongruent Resolution | Contextual Processing | ||

| Analysis Steps | Emergent Analysis | Traits Coding | Holistic Coding | Holistic Interpretation (Metaphor Construction) | Textual Alignment |

|

| Specific traits:

Multilingual identity as a growing brain (a body part). | Evolving, functioning, compositional | Dynamism of identities Annie employed visual metaphors to convey the concept that identities are dynamic rather than static. In her conceptualisation, dynamism is a salient feature throughout all her pieces. The drawings are only snapshots of an ever-changing state. The evolution of identities stems from their diverse and mutable components, and Annie can exercise agency in changing them. | “The brain evolves as new languages are learnt.” “We change [as we] discover different parts of ourselves.” “This portrait shows how I have different parts of myself that each language contributes to, and that each language is its own part of my identity.” |

|

| Specific traits:

Intercultural identity as a container in which things can be included, excluded, and mixed. | Dispersal, flexible, customisable | “As a ‘Serb’ born in Australia, I am already quite mixed in cultures, which is shown by the abundant bowl of noodles.” “The noodles and soup puddles on the table represent the parts of my identity I have chosen to discard or have forgotten over time” “The seasoning is resemblant of the constant addition with experiences of new cultures.” | |

|

| Specific traits:

Study abroad as a book chapter in a life story. | Transforming, forward-looking | “To visualise changes to my identity, it’s first important to think about life as a book where every experience falls under one chapter.” “The first page of my drawing is the ending of this experience, while the bookmark shows that the reader (me) intends to keep reading to sculpt their perceptions in life.” | |

Appendix C. Detailed Analysis of Jack’s Drawings

| Model of Visual Metaphor Processing Stages | Incongruent Perception | Incongruent Resolution | Contextual Processing | ||

| Analysis Steps | Emergent Analysis | Traits Coding | Holistic Coding | Holistic Interpretation (Metaphor Construction) | Textual Alignment |

|

| Specific traits:

Multilingual identity as an unstable structure dominated by one language but open to change. | Segmented, colourful, patterned; blending abstract and figurative; weaving | Blending of identities Jack exemplifies the blending of dual cultural influences that heritage learners experience. His drawings capture the interaction of two distinct yet interwoven influences within his identity. This blending is represented by the merging of abstract and figurative elements in his first two drawings. The process remains fluid, and the experience of studying abroad has significantly clarified his cultural identity rooted in Chinese heritage, highlighting the varying contexts in which one influence becomes more pronounced than another. | “My face is composed yet layered, representing the multifaceted nature of my linguistic self.” “English… is symbolically etched into my very being, as indicated by the prominence of the Australian flag.” “English is the language in which I feel most articulate and authentic.” “This portrayal is not static. As my proficiency in Chinese grows, I might find new ways to weave it into the fabric of my identity.” |

|

| Specific traits:

Intercultural identity as a complex structure dominated by Chinese culture with other cultural influences. | Segmented, colourful, patterned; blending abstract and figurative; weaving | “The bold, unmistakable presence of the Chinese flag stands out… This reflects the deep-seated influence of Chinese culture in my life” “The Australian cultural influence, depicted through the presence of its colours but the absence of a coherent flag, suggests that …it remains a fluid and unstructured part of my identity… it exists around the edges, colouring my experiences and perspective but not forming the core of who I am. | |

|

| Specific traits:

Study abroad as a reaffirmation of his Chinese heritage. | Clear, minimalist | “The Chinese stars are placed squarely in the heart region… speaks to how my essence pulsates with the rhythms and tenets of Chinese culture” “The stark simplicity of the design… reflects a clarity of realisation… of the depth of my Chinese identity.” “[It] captures the ongoing evolution of my identity as it becomes increasingly informed by my heritage” | |

Appendix D. Detailed Analysis of Hana’s Drawings

| Model of Visual Metaphor Processing Stages | Incongruent Perception | Incongruent Resolution | Contextual Processing | ||

| Analysis Steps | Emergent Analysis | Traits Coding | Holistic Coding | Holistic Interpretation (Metaphor Construction) | Textual Alignment |

|

| Specific traits:

Multilingual identity as a mosaic of linguistic uses. | Mosaic, Hierarchical, diverse | Layeredness of identities Hana’s case illustrates the layeredness of her identity development. Acquiring new languages and exposure to different cultures contribute additional layers to her multilingual and intercultural identities. These identities vary in prominence across different contexts. Her experience studying abroad in China enhanced her intercultural identity, resulting in a reduced emphasis on the Japanese aspect of her identity. | “I speak Japanese as my native language and I mainly speak English outside of my house so those two languages are my main language as shown in the representation.” “I’m learning Korean and Chinese and those two languages are also a part of my multilingual identity although I don’t speak as well as my main languages.” “I also drew some factors such as environment and motivation that influences my language identity.” |

|

| Specific traits:

Intercultural identity grows under closer and more remote influences | Layered, hierarchical, evolving | “Despite my international experience, I still feel like my cultural identity is Japanese.” “On top of my Japanese cultural, there is Australian culture that shapes who I am and also another Japanese cultural identity that I didn’t realise until I live in foreign country as Japanese.” “My intercultural identity is also influenced by my travel experience to countries like US, Canada, China and Korea. I think traveling always gives me new sense of cultural identity.” | |

|

| Specific traits:

Study abroad adds or removes layers of identities | Adding and removing layers | “I was able to improve my Chinese ability and expand my knowledge about Chinese culture and I represent it as a new leaf.” “Although I always recall my culture identity as Japanese whenever I’m overseas, I first time recognise that Australian culture was also a big part of my identity now by sharing stories in China as an Australian university student.” | |

References

- Ahn, S.-Y. (2021). Visualizing the interplay of fear and desire in English learner’s imagined identities and communities. System, 102, 102598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.-Y., & West, G. B. (2017). Young learners’ portrayals of ‘good English teacher’ identities in South Korea. Applied Linguistics Review, 9, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alred, G. (2002). Becoming a ‘better stranger’: A therapeutic perspective on intercultural experience and/as education. In M. B. Alred, & M. Fleming (Eds.), Intercultural experience and education (pp. 14–30). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Bessette, H. J., & Paris, N. A. (2020). Using visual and textual metaphors to explore teachers’ professional roles and identities. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 43(2), 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, J. (2011). Intercultural identities: Addressing the global dimension through art education. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 30(2), 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, M. (1979). More about metaphor. In A. Ortony (Ed.), Metaphor and thought (pp. 19–43). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Block, D. (2015). Becoming multilingual and being multilingual: Some thoughts. In J. Cenoz, & D. Gorter (Eds.), Multilingual education: Between language learning and translanguaging (pp. 225–237). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blommaert, J. (2010). The sociolinguistics of globalization. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, T., & Max Evans, M. (2019). Shedding light on “knowledge”: Identifying and analyzing visual metaphors in drawings. Metaphor and Symbol, 34(4), 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, B. (2018). The language portrait in multilingualism research: Theoretical and methodological considerations. Working Papers in Urban Language & Literacies, 236, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chik, A. (2017). Beliefs and practices of foreign language learning: A visual analysis. Applied Linguistics Review, 9, 307–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X. (2013). Four perspectives of interpreting intercultural identity. Academic Research, 9, 144–160. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, F., Soleimanzadeh, S., Zhang, W. Q., & Shirvan, M. E. (2023). Chinese students’ multilingual identity constructions after studying abroad: A multi-theoretical perspective. System, 115, 103053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, L., Evans, M., Forbes, K., Gayton, A., & Liu, Y. C. (2020). Participative multilingual identity construction in the languages classroom: A multi-theoretical conceptualisation. International Journal of Multilingualism, 17(4), 448–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forceville, C. (2008). Metaphor in pictures and multimodal representations. In R. W. Gibbs (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of metaphor and thought (pp. 462–482). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gauntlett, D. (2007). Creative explorations: New approaches to identities and audiences. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S. (2010). The homecoming: An investigation into the effect that studying overseas had on Chinese postgraduates’ life and work on their return to China. Compare—A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 40(3), 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haukås, Å., Storto, A., & Tiurikova, I. (2021). Developing and validating a questionnaire on young learners’ multilingualism and multilingual identity. Language Learning Journal, 49(4), 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, A. (2017). L2 Motivation and multilingual identities. The Modern Language Journal, 101(3), 548–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y. T., & Dai, K. (2021). Foreign-born Chinese students learning in China: (Re)shaping intercultural identity in higher education institution. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 80, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N. (2019). Children’s multimodal visual narratives as possible sites of identity performance. In P. Kalaja, & S. Melo-Pfeifer (Eds.), Visualising multilingual lives: More than words (pp. 33–52). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, T. H., & O’Regan, J. P. (2024). “I told them I want to speak Chinese!” The struggle of UK students to negotiate language identities while studying Chinese in China. British Journal of Educational Studies, 72(4), 501–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, R. V. (2021). ‘Then suddenly I spoke a lot of Spanish’—Changing linguistic practices and heritage language from adolescents’ points of view. International Multilingual Research Journal, 15(2), 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaja, P., & Melo-Pfeifer, S. (Eds.). (2019). Visualising multilingual lives: More than words. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. Y. (2008). Intercultural personhood: Globalization and a way of being. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32(4), 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, J. G., & Cole, A. L. (Eds.). (2012). Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues. SAGE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramsch, C. (2016). Multilingual identity and ELF. In M. Pitzl, & R. Osimk-Teasdale (Eds.), English as a lingua franca: Perspectives and prospects (pp. 179–186). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Kramsch, C., & Uryu, M. (2012). Intercultural contact, hybridity, and third space. In The Routledge handbook of language and intercultural communication (p. 15). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, S. (1948). Philosophy in a new key. A study in the symbolism of reason, rite, and art. New American Library. [Google Scholar]

- Leavy, P. (2009). Method meets art: Arts-based research practice. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, M.-Y. (2019). Beyond elocution: Multimodal narrative discourse analysis of L2 storytelling. ReCall, 31(1), 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeder-Qian, J. Y. (2018). Intercultural experiences and cultural identity reconstruction ofmultilingual Chinese international students in Germany. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 39(7), 576–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maijala, M. (2021). Multimodal postcards to future selves: Exploring pre-service language teachers’ process of transformative learning during one-year teacher education programme. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 17, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B. (2012). Coloured language: Identity perception of children in bilingual programmes. Language Awareness, 21(1–2), 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo-Pfeifer, S. (2015). Multilingual awareness and heritage language education: Children’s multimodal representations of their multilingualism. Language Awareness, 24(3), 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo-Pfeifer, S., & Schmidt, A. F. (2019). Integration as portrayed in visual narratives by young refugees in Germany. In P. Kalaja, & S. Melo-Pfeifer (Eds.), Visualising multilingual lives: More than words (pp. 53–72). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, C. (2011). Doing visual research. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Molinié, M. (2019). From the migration experience to its visual narration in international mobility. In P. Kalaja, & S. Melo-Pfeifer (Eds.), Visualising multilingual lives: More than words (pp. 73–94). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, B. (2000). Identity and language learning: Gender, ethnicity and educational change. Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlenko, A. (2006). Bilingual minds: Emotional experience, expression, and representation. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlenko, A., & Blackledge, A. (2004). Negotiation of identities in multilingual contexts. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, T., & Menard-Warwick, J. (2021). Translingual and transcultural reflection in study abroad: The case of a Vietnamese-American student in Guatemala. The Modern Language Journal, 105(1), 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refaie, E. E. (2003). Understanding visual metaphor: The example of newspaper cartoons. Visual Communication, 2(1), 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, G. (2016). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials (4th ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Skinnari, K. (2019). Looking but not seeing: The hazards of a teacher-researcher interpreting self-portraits of adolescent English learners. In P. Kalaja, & S. Melo-Pfeifer (Eds.), Visualising multilingual lives: More than words (pp. 97–114). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Stavrakaki, A., & Manoli, P. (2023). Exploring migrant students’ attitudes towards their multilingual identities through language portraits. Societies, 13(7), 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šorm, E., & Steen, G. (2013). Processing visual metaphor: A study in thinking out loud. Metaphor and the Social World, 3(1), 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J., Zhao, K., & Dong, W. (2022). A multimodal analysis of the online translanguaging practices of international students studying Chinese in a Chinese university. Applied Linguistics Review, 15, 1531–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, P., An, I. S., & Zhou, Y. (2022). Developmental ecosystems of study abroad in a turbulent time: An Australian-Chinese’s experience in multilingual Hong Kong. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 43(8), 796–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, P., & Tsung, L. (2022). Learning Chinese in a multilingual space: An ecological perspective on study abroad. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, P., & Tsung, L. (2023). Different Trajectories of heritage language identity development through short-term study abroad programs: The case of chinese heritage learners. Sustainability, 15(8), 6392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vande Berg, M., Paige, R. M., & Lou, K. H. (Eds.). (2012). Student learning abroad: What our students are learning, what they’re not, and what we can do about it (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang-Wu, Q. (2023). Asian students in American higher education: Negotiating multilingual identities in the era of superdiversity and nationalism. Language and Intercultural Communication, 23, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pseudonym | Languages | Cultural Heritage | Place of Birth | First and Home Language | Dominant Language(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annie | English, Serbian, Mandarin, French | Serbian | Australia | Serbian | English, Serbian |

| Jack | English, Cantonese Mandarin | Chinese | Australia | Cantonese | English |

| Hana | English, Japanese, Mandarin, Korean | Japanese | Japan | Japanese | English, Japanese |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tong, P.; An, I.S.; Zhang, X. Visualising the Fluidity of Multilingual and Intercultural Identities of Australian University Students Studying Abroad in China. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1608. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121608

Tong P, An IS, Zhang X. Visualising the Fluidity of Multilingual and Intercultural Identities of Australian University Students Studying Abroad in China. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1608. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121608

Chicago/Turabian StyleTong, Peiru, Irene Shidong An, and Xin Zhang. 2025. "Visualising the Fluidity of Multilingual and Intercultural Identities of Australian University Students Studying Abroad in China" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1608. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121608

APA StyleTong, P., An, I. S., & Zhang, X. (2025). Visualising the Fluidity of Multilingual and Intercultural Identities of Australian University Students Studying Abroad in China. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1608. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121608