Use of Active Methodologies in Basic Education: An Umbrella Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Strategy

2.2. Data Selection Process

- Year of publication: last six years up to the present (2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023), to capture recent, comparable evidence during a period of rapid pedagogical change.

- Research domain: educational research (WoS) and social sciences (Scopus).

- Language: English and Spanish.

- Document type: articles and review articles.

- Records that did not contain the specified descriptors in the title, keywords, or abstract, or that, although including them, did not fit the research topic.

- Results whose content did not correspond to the required language, research domain, or document type.

- Primary studies and narrative reviews without an explicit method/synthesis, given that the design required reviews with an explicit synthesis.

- Reviews that did not verifiably report sources/search dates, search terms, and eligibility criteria, preventing traceability.

- Lack of access to the full text.

2.3. Data Extraction Process

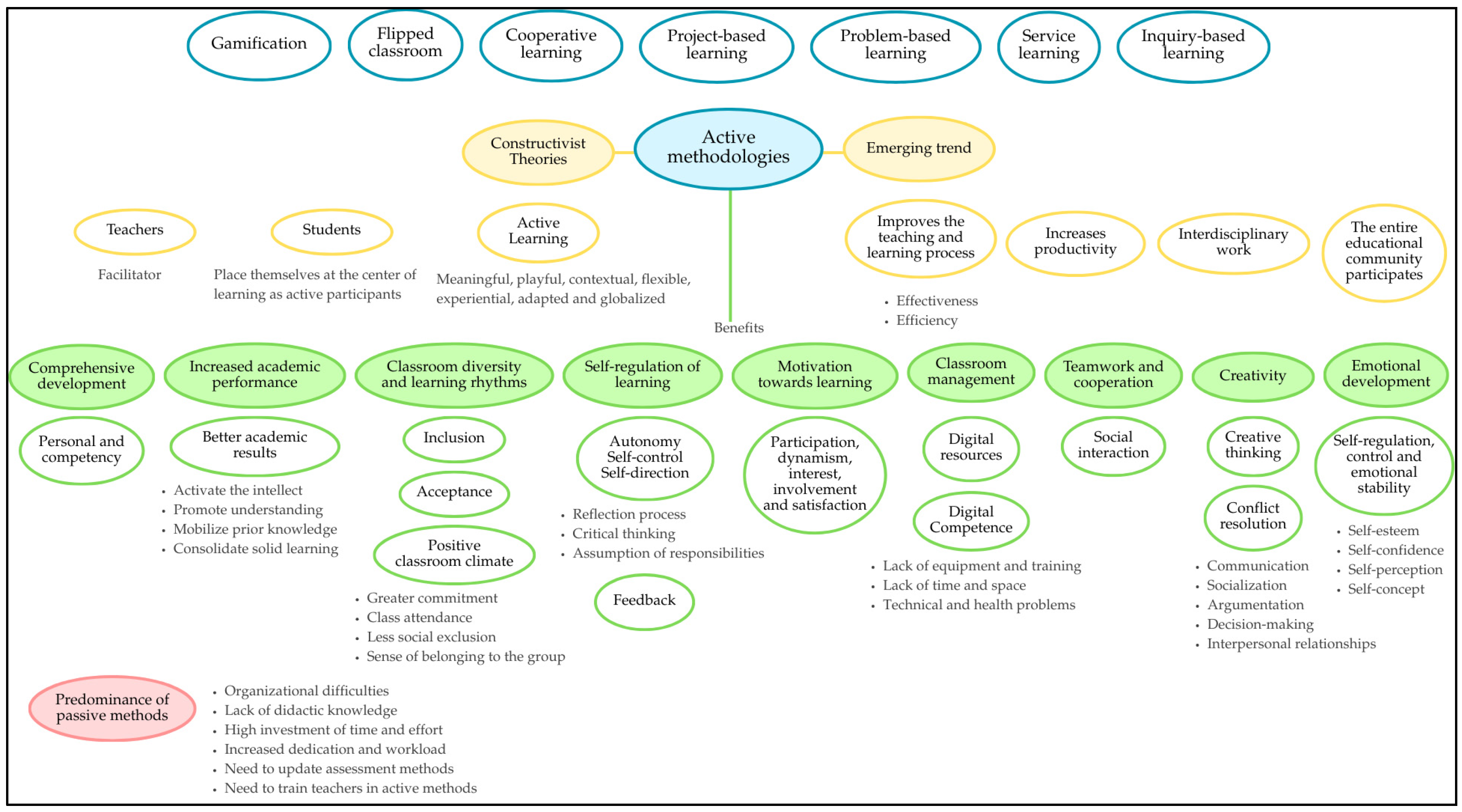

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WoS | Web of Science |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| EACSH | Scale for Evaluating Scientific Articles in the Social Sciences and Humanities, Spanish acronym |

Appendix A

References

- Aguilera Eguía, R., & Arroyo Jofre, P. (2016). ¿Revisión sistemática?, ¿metaanálisis? o ¿resumen de revisiones sistemáticas? Nutrición Hospitalaria, 33(2), 503–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz García, S. (2021). Investigación educativa sobre trastorno del espectro autista: Un análisis bibliométrico. Bordón Revista de Pedagogía, 73(3), 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arán Sánchez, A., Arzola Franco, D. M., & Ríos Cepeda, V. L. (2021). Enfoques en el currículo, la formación docente y metodología en la enseñanza y aprendizaje del inglés: Una revisión de la bibliografía y análisis de resultados. Revista Educación, 46(1), 538–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arufe-Giráldez, V., Sanmiguel-Rodríguez, A., Ramos-Álvarez, O., & Navarro-Patón, R. (2022). Gamification in physical education: A systematic review. Education Sciences, 12, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazurto-Briones, N. A., & García-Vera, C. E. (2021). Flipped classroom con edpuzzle para el fortalecimiento de la comprensión lectora. Polo del Conocimiento, 6(3), 324–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belbasis, L., Bellou, V., & Ioannida, J. P. A. (2022). Conducting umbrella reviews. BMJ Medicine, 1, e000071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belduma-Suquilanda, R. M. (2021). Aprendizaje basado en problemas como estrategia para mejorar los procesos comunicacionales en el aula. Polo del Conocimiento, 6(3), 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez Mendieta, J. (2021). El aprendizaje basado en problemas para mejorar el pensamiento crítico: Revisión sistemática. Innova Research Journal, 6(2), 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boix Vilella, S., & Ortega Rodríguez, N. (2020). Beneficios del aprendizaje cooperativo en las áreas troncales de Primaria: Una revisión de la literatura científica. ENSAYOS Revista de la Facultad de Educación de Albacete, 35(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo Varela, D., Sotelino Losada, A., & Rodríguez Fernández, J. E. (2019). Aprendizaje-servicio e inclusión en educación primaria. Una revisión sistemática desde la Educación Física. Retos, 36, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Rodríguez, C., & Prat Fernández, B. (2022). Cooperative learning in the CLIL classroom: Challenges perceived by teachers and recommendations for primary education. Educatio Siglo XXI, 40(1), 79–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codina, L., Morales-Vargas, A., Rodríguez-Martínez, R., & Pérez-Montoro, M. (2020). Uso de scopus y web of science para investigar y evaluar en comunicación social: Análisis comparativo y caracterización. Comunicación, 10(3), 235–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisol-Moya, E., Romero-López, M. A., & Caurcel-Cara, M. J. (2020). Active methodologies in higher education: Perception and opinion as evaluated by professors and their students in the teaching-learning process. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Molano, E., Sánchez-Cid, M., & Matosas-López, L. (2019). Análisis bibliométrico de estudios sobre la estrategia de contenidos de marca en los medios sociales. Comunicación y Sociedad, 16, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daher, M., Rosati, A., Hernández, A., Vásquez, N., & Tomicic, A. (2022). TIC y metodologías activas para promover la educación universitaria integral. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado Vázquez, A., Vázquez-Cano, E., Belando Montoro, M. R., & López Meneses, E. (2019). Análisis bibliométrico del impacto de la investigación educativa en diversidad funcional y competencia digital: Web of science y scopus. Aula Abierta, 48(2), 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolittle, P., Wojdak, K., & Walters, A. (2023). Defining active learning: A restricted systematic review. Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 11, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, E. (2020). Student teachers’ perceptions, experiences, and challenges regarding learner-centred teaching. South African Journal of Education, 40(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, B., Shen, Y., Xiong, W., & Dang, L. (2022). How cooperative learning is conceptualized and implemented in Chinese physical education: A systematic review of literature. ECNU Review of Education, 5(1), 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escaravajal Rodríguez, J. C., & Martín-Acosta, F. (2019). Análisis bibliográfico de la gamificación en educación física. Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencias de la Actividad Física y el Deporte, 8(1), 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza Freire, E. E. (2022). El trabajo colaborativo en la enseñanza-aprendizaje de la Geografía. Revista Universidad y Sociedad, 14(2), 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Olivero, E. D., & Simón Medina, N. M. (2022). Revisión bibliográfica sobre el uso de metodologías activas en la Formación Profesional. Contextos Educativos. Revista de Educación, 30, 131–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, M., Vadillo, M. A., & León, S. P. (2021). Is project-based learning effective among kindergarten and elementary students? A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 6(4), e0249627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firman, M. A., Ertikanto, C., & Abdurrahman, A. (2019). Description of meta-analysis of inquiry-based learning of science in improving students’ inquiry skills. Journal of Physics, 1157, 022018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombona, J., Pascual, M. A., & Sevillano, M. L. (2020). Construcción del conocimiento en los niños basado en dispositivos móviles y estrategias audiovisuales. Educaçao & Sociedade, 41, e216616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornons, V., & Palau, R. (2021). Flipped classroom en la enseñanza de las matemáticas: Una revisión sistemática. Education in the Knowledge Society, 22, e24409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(23), 8410–8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosálbez-Carpena, P. A., García-Martínez, S., García-Jaén, M., Østerlie, O., & Ferriz-Valero, A. (2022). Aplicación metodológica flipped classroom y educación física en enseñanza no universitaria: Una revisión sistemática. Journal of Sport and Health Research, 14(2), 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guamán Gómez, V. J., & Espinoza Freire, E. E. (2022). Aprendizaje basado en problemas para el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje. Universidad y Sociedad, 14(2), 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Heindl, M. (2019). Inquiry-based learning and the pre-requisite for its use in science at school: A meta-analysis. Journal of Pedagogical Research, 3(2), 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellín Martínez, M., Alfonso Asencio, M., & Sánchez-Alcaraz Martínez, B. J. (2020). Revisión sistemática del modelo de enseñanza de aprendizaje servicio en educación física: Aspectos clave y principios para su aplicación práctica. Revista Digital de Educación Física, 66, 10–22. [Google Scholar]

- Heredia Ponce, H., Romero Oliva, M. F., & Romero Claudio, C. (2022). Language teaching through the flipped classroom: A systematic review. Education Sciences, 12, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, A. J., Sánchez-Alcaraz, B. J., Alfonso-Asencio, M., & Hellín-Martínez, M. (2021). Gamificación en educación física: Revisión sistemática. Trances: Revista de Transmisión del Conocimiento Educativo y de la Salud, 14(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Herrada Valverde, R. I., & Baños Navarro, R. (2018). Aprendizaje cooperativo a través de las nuevas tecnologías: Una revisión. Revista D’Innovació Educativa, 20, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, G., Keramopoulos, E., Diamantaras, K., & Evangelidis, G. (2022). Augmented reality and gamification in education: A systematic literature review of research, applications, and empirical studies. Applied Sciences, 12(13), 6809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Díaz, O., Martínez-Muñoz, L. F., & Santos-Pastor, M. L. (2018). Análisis de la investigación sobre aprendizaje basado en proyectos en educación física. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 21(2), 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Díaz, O., Martínez-Muñoz, L. F., & Santos-Pastor, M. L. (2019). Gamificación en educación física: Un análisis sistemático de fuentes documentales. Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencias de la Actividad Física y el Deporte, 8(1), 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Zowghi, D., Kearney, M., & Bano, M. (2021). Inquiry-based mobile learning in secondary school science education: A systematic review. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 37, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-de-Arana Prado, E., Vizcarra Morales, M. T., & Calle-Molina, M. T. (2023). Revisión sobre los beneficios psicosociales que las personas receptoras obtienen del aprendizaje-servicio en actividad física y deportiva. Bordón Revista de Pedagogía, 75(1), 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López, E., Tobón, S., & Juárez-Hernández, L. G. (2019). Escala para evaluar artículos científicos en ciencias sociales y humanas-EACSH. REICE. Revista Iberoamericana sobre la Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 17(4), 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maside Pujol, C., & González García, H. (2022). Una revisión narrativa sobre el voluntariado en la educación secundaria obligatoria. Escuela Abierta, 25, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Mata, I., & Peirats, J. (2019). Aprendizaje basado en Proyectos en Educación Física en Primaria, un estudio de revisión. Reidocrea: Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Docencia Creativa, 8(2), 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntaner, J. J., Mut, B., & Pinya, C. (2022). Las metodologías activas para la implementación de la educación inclusiva. Revista electrónica Educare, 26(2), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty, J., & Phillips, C. (2015). The use of flipped classrooms in higher education: A scoping review. Internet and Higher Education, 25, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olry de Labry Lima, A., Mendoza García, O. J., & Mena Jiménez, A. L. (2016). Más allá de las revisiones sistemáticas. Boletín Psicoevidencias, 44, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Opanga, D., & Venuste, N. (2022). The effect of the use of English as language of instruction and inquiry-based learning on biology learning in Sub-Saharan Africa secondary schools: A systematic review of the literature. African Journal of Research in Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 26(3), 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez Ocampo, B. P., Ochoa Romero, M. E., Erráez Alvarado, J. L., León González, J. L., & Espinoza Freire, E. E. (2021). Consideraciones sobre aula invertida y gamificación en el área de ciencias sociales. Revista Universidad y Sociedad, 13(3), 497–504. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco, I., & Moriña, A. (2020). Estrategias metodológicas que promueven la inclusión en educación infantil, primaria y secundaria. Revista Internacional de Educación para la Justicia Social, 9(1), 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco Sanz, D. I., Canedo García, A., Martín Sánchez, B., Bleye Varona, Y., & Gago Morate, A. (2020). El trabajo por proyectos en el currículo educativo: Principios metodológicos que lo fundamentan. INFAD Revista de Psicología, 2(1), 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grumshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … McKenzie, J. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paños Castro, J. (2017). Educación emprendedora y metodologías activas para su fomento. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 20(3), 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastes Urbano, L. M., Terán, H. S., Sotelo Gómez, F., Solarte, M. F., Sepulveda, C. J., & López Meza, J. M. (2020). Bibliographic review of the flipped classroom model in high school: A look from the technological tools. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 19, 451–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, R. D., Peixoto, B., Melo, M., Cabral, L., & Bessa, M. (2021). Foreign language learning gamification using virtual reality—A systematic review of empirical research. Education Sciences, 11(5), 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro Aboy, B. (2022). Los efectos de la gamificación en el alumnado de educación física escolar. Revistas UVigo, 2(1), 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Corcobado, P., & Fuentes, J. L. (2020). La investigación sobre el aprendizaje-servicio en la producción científica española: Una revisión sistemática. Revista Complutense de Educación, 31(1), 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, V. (2022). ¿Cambiar la escuela o mejorarla? Lectio. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Hidalgo, D., & Ortega-Sánchez, D. (2022). El aprendizaje basado en proyectos: Una revisión sistemática de la literatura (2015–2022). Revista Internacional de Humanidades, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Robles, A., Parra-González, M. E., & Gallardo-Vigil, M. A. (2020). Análisis bibliométrico y de redes de colaboración sobre metodologías activas en educación. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, 9(2), 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Quiroz, J., & Maturana Castillo, D. (2017). Una propuesta de modelo para introducir metodologías activas en educación superior. Innovación Educativa, 17, 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Silva Souza, D., & Santos Silva, C. C. (2021). Metodologias ativas no ensino da matemática: (Re)pensando a prática docente. Revista Educação a distância e Práticas Educativas Comunicacioanis e Interculturais, 21(1), 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón, C., Muñoz-Martínez, Y., & Porter, G. L. (2021). Instrucción y prácticas en el aula que llegan a todos los alumnos. Revista de Educación de Cambridge, 51(5), 607–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K. S. (2024). Educational constructivism. Encyclopedia, 4(4), 1534–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theobald, E. J., Hill, M. J., Tran, E., Agrawal, S., Arroyo, E. N., Behling, S., Chambwe, N., Cintrón, D. L., Cooper, J. D., Dunster, G., Grummer, J. A., Hennessey, K., Hsiao, J., Iranon, N., Jones, L., Jordt, H., Keller, M., Lacey, M. E., Littlefield, C. E., … Freeman, S. (2020). Active learning narrows achievement gaps for underrepresented students in undergraduate science, technology, engineering, and math. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(12), 6476–6483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsehay, S., Belay, M., & Seifu, A. (2024). Challenges in constructivist teaching: Insights from social studies teachers in middle-level schools, West Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia. Cogent Education, 11(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urdanivia Alarcon, D. A., Talavera-Mendoza, F., Rucano Paucar, F. H., Cayani Caceres, K. S., & Machaca Viza, R. (2023). Science and inquiry-based teaching and learning: A systematic review. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, A., & Janssen, J. (2019). A systematic review of teacher guidance during collaborative learning in primary and secondary education. Educational Research Review, 27, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapatero Ayuso, J. A. (2017). Beneficios de los estilos de enseñanza y las metodologías centradas en el alumno en Educación Física. Revista de Ciencias del Deporte, 13(3), 237–250. [Google Scholar]

| Search Terms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “gamification” OR “gamificación” | AND | “primary education” OR “secondary education” OR “basic education” OR “educación secundaria” OR “educación primaria” OR “educación básica” | AND | “review” OR “revisión” |

| “flipped classroom” OR “inverted classroom” OR “clase invertida” | ||||

| “cooperative learning” OR “aprendizaje cooperativo” | ||||

| “project-based learning” OR “aprendizaje basado en proyectos” | ||||

| “problem-based learning” OR “aprendizaje basado en problemas” | ||||

| “service learning” OR “aprendizaje servicio” | ||||

| “inquiry-based learning” OR “aprendizaje basado en la indagación” | ||||

| Active Methodologies | Identification | Screening | Eligibility | Inclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Documents Identified | No. of Documents After Applying Filters | No. of Most Cited Documents Included in the Analysis | ||

| Gamification | WoS: 51 | WoS: 24 | 5 | |

| Scopus: 49 | Scopus: 19 | |||

| Dialnet: 199 | Dialnet: 130 | |||

| Flipped classroom | WoS: 35 | WoS: 12 | 5 | |

| Scopus: 32 | Scopus: 12 | |||

| Dialnet: 23 | Dialnet: 14 | |||

| Cooperative learning | WoS: 70 | WoS: 15 | 5 | |

| Scopus: 57 | Scopus: 23 | |||

| Dialnet: 117 | Dialnet: 69 | |||

| Project-based learning | WoS: 53 | WoS: 9 | 5 | |

| Scopus: 72 | Scopus: 17 | |||

| Dialnet: 69 | Dialnet: 47 | |||

| Problem-based learning | WoS: 50 | WoS: 8 | 3 | |

| Scopus: 68 | Scopus: 14 | |||

| Dialnet: 73 | Dialnet: 60 | |||

| Service learning | WoS: 34 | WoS: 6 | 5 | |

| Scopus: 32 | Scopus: 7 | |||

| Dialnet: 104 | Dialnet: 70 | |||

| Inquiry-based learning | WoS: 74 | WoS: 20 | 5 | |

| Scopus: 51 | Scopus: 20 | |||

| Dialnet: 13 | Dialnet: 6 | |||

| Total | 1326 documents | 602 documents | 33 documents | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González López, A.M.; Pascual Sevillano, M.Á.; Sorzio, P. Use of Active Methodologies in Basic Education: An Umbrella Review. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1536. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111536

González López AM, Pascual Sevillano MÁ, Sorzio P. Use of Active Methodologies in Basic Education: An Umbrella Review. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1536. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111536

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález López, Andrea María, María Ángeles Pascual Sevillano, and Paolo Sorzio. 2025. "Use of Active Methodologies in Basic Education: An Umbrella Review" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1536. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111536

APA StyleGonzález López, A. M., Pascual Sevillano, M. Á., & Sorzio, P. (2025). Use of Active Methodologies in Basic Education: An Umbrella Review. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1536. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111536