1. Introduction

Inclusive education is widely recognized as a central pillar of social sustainability, as it fosters equity, active participation, and social cohesion (

Ainscow, 2020;

Loreman, 2017;

Yang et al., 2025). By ensuring equitable access to education for all social groups, including students with disabilities, inclusive practices reduce marginalization and systemic inequalities. In alignment with Goal 4 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by the United Nations, it is imperative to guarantee quality, equitable, and inclusive education for all, by eliminating structural and attitudinal barriers that affect vulnerable groups (

United Nations, 2015). However, mere physical proximity does not guarantee genuine inclusion; it requires systemic reform involving equitable resource allocation, curriculum redesign, and inclusive institutional policies (

Yang et al., 2025). Inclusive education also requires curriculum adaptations, differentiated instruction, institutional structures, and inclusive pedagogical values (

Florian & Black-Hawkins, 2013). More recent work warns against “fauxclusion”—integrating students with disabilities into mainstream settings without systemic reform—and stresses the need for transforming teaching methods, curricula, and support systems to ensure full participation by all learners (

Yang et al., 2025). Throughout this paper, we intentionally use person-first, affirming, and strengths-based language that reflects inclusive and socially grounded communication practices; when stereotype-laden phrasing appears (e.g., in measurement items), it is explicitly marked as such and used only for diagnostic purposes.

Inclusive education has recently been defined as a transformative approach that aims to eliminate barriers and promote full participation for all learners, especially people with disabilities through systemic reforms in pedagogy, curriculum, and institutional culture—including teacher training for inclusive practices, the adaptation of curricular content and assessment methods, and the redesign of institutional environments to ensure accessibility and equity (

Oswal et al., 2025;

Anderson et al., 2024). From a contemporary perspective, disability is understood not merely as a set of individual differences, but as the outcome of interactions between individual physical, cognitive, and emotional characteristics and environmental barriers that hinder active engagement in academic and social life (

Sadzaglishvili et al., 2025). Consistent with this social–relational view, we use “impairment” only when reproducing language from cited sources and otherwise prefer barrier-focused formulations. Furthermore, attitudes toward people with disabilities are conceptualized as multidimensional constructs—encompassing cognitive, emotional, and behavioral components—that shape social interactions and inclusion outcomes in educational settings (

Sadzaglishvili et al., 2025;

Abed et al., 2024). It is important to distinguish between the concept of disability and attitudes toward inclusion. Disability, as framed in this study, refers to the interaction between individual characteristics and contextual barriers that restrict participation. In contrast, attitudes toward inclusion reflect individuals’ beliefs, emotions, and behavioral intentions regarding the integration of people with disabilities into mainstream educational environments. While disability concerns the lived experiences of those affected, inclusive attitudes denote how others—such as peers, educators, or institutional actors—perceive and respond to the presence of disability within shared spaces. Understanding this distinction is critical for developing effective interventions, as reducing stigma and fostering inclusion require not only accommodation but also attitudinal change at multiple levels. These clarifications guide both our analytic choices and our language policy in the manuscript.

These definitions reflect a shift from deficit-based models toward inclusive paradigms grounded in human rights, cultural responsiveness, and sustainable development.

Educational inclusion is not only a moral or legal obligation but also a prerequisite for building resilient and democratic societies, as it fosters participation, equity, and recognition of diversity as a civic value (

Slee, 2011).

Inclusive education also depends on cultivating social–emotional competencies such as tolerance. Recent studies highlight that, despite policy intent, classroom tolerance toward students with disabilities remains underdeveloped in many regions. For example, in several primary school settings, 38.6% of students with special educational needs (terminology reproduced from the original source) reported experiencing bullying, compared to only 4.8% among their typically developing peers (

Carmona & Montanero, 2025). Another review across 13 countries identified persistent barriers, including insufficient teacher preparation for inclusive and special education practices, and limited attention to the emotional dimensions of inclusion (

Deroncele-Acosta & Ellis, 2024). These issues are especially pronounced in low- and middle-income countries, where systemic barriers exacerbate exclusion and stigma. For instance, recent research in Colombia found that a significant proportion of undergraduate students who identify as having a disability report persistent barriers to inclusion in higher education, including inadequate pedagogical support and social isolation (

Carrillo-Sierra et al., 2025). Such findings underscore the urgency of embedding tolerance-focused strategies and anti-bullying measures in teacher education, school curricula, and institution-wide policies, especially in under-resourced environments. An education system open to diversity supports fundamental democratic values such as mutual respect, empathy, and acceptance of differences, thereby enabling full participation in social life. Universities and academic institutions should strive to ensure that the learning environment is accessible, adapted, and responsive to the needs of all students, particularly in contexts where structural barriers persist or resources are limited. A critical factor for the success of inclusion in higher education is the attitude of students without disabilities, which significantly influences the social and academic integration of their peers with disabilities. Systemic barriers and faculty perceptions play a crucial role in shaping these attitudes (

Mashwama & Omodan, 2024). Positive attitudes are associated with increased well-being, motivation, and academic performance for students with disabilities, and contribute to an inclusive and sustainable institutional culture (

Shutaleva et al., 2023;

Avramidis & Norwich, 2002). Therefore, a deeper understanding of the factors that shape and transform these attitudes is essential. Recent research has highlighted that individual differences such as gender and tolerance levels may significantly moderate attitudes toward people with disabilities. Female students tend to express more favorable views and greater empathy, possibly due to gendered patterns of socialization and emotional responsiveness (

Strnadova et al., 2023;

Nowicki, 2006). At the same time, higher levels of social tolerance are associated with reduced bias and more positive perceptions of marginalized groups, including communities of people with disabilities (

Costantini et al., 2024). These findings support a multidimensional understanding of inclusive attitudes and provide a robust theoretical rationale for investigating the moderating roles of gender and tolerance in attitudinal change.

Existing literature suggests that educational interventions using emotional stimuli—particularly media-based content—can effectively influence attitudes, especially when correlated with individual variables such as gender and tolerance (

Ambika & Vayola, 2023).

This study aims to empirically investigate how the type of video message, gender, and tolerance level influence students’ attitudes toward people with disabilities, within a rigorously controlled experimental design. Similar findings have been reported in pre-university settings, where peers’ attitudes have been shown to play a critical role in facilitating social participation and academic progress for people with disabilities (

Townsend et al., 2024).

To enhance transparency regarding the study’s conceptual framing, we include below an Authors’ Reflexivity Statement outlining the rationale for our analytical choices.

Authors’ Reflexivity Statement: Although the concept of disability encompasses a wide spectrum of physical, sensory, intellectual, and psychosocial forms of human diversity, this study analyzes attitudes toward a general construct for analytic clarity, in line with the general framework of inclusive education and public discourse. We recognize that this choice may obscure heterogeneity across disability communities; accordingly, we treat it as a methodological simplification and a limitation that future work should address through finer-grained, community-informed designs.

We acknowledge that attitudes toward people with disabilities can vary significantly depending on the type and severity of the condition (e.g., visible vs. invisible disabilities, mild vs. complex support needs), which may influence attribution of abilities and social judgments. However, the current research aimed to capture general attitudinal trends toward the broader concept of disability, as reflected in international and institutional educational inclusion policies—such as those promoted by UNESCO’s Education 2030 Framework for Action (

UNESCO, 2015) and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (

United Nations, 2006). The lack of differentiation between disability types is acknowledged as a limitation and a direction for future research.

1.1. Formation of Attitudes Toward People with Disabilities

In academic literature, attitudes are defined as favorable or unfavorable evaluations of a person, object, or idea, which influence behavior (

Rojo-Ramos et al., 2023). Attitudes consist of cognitive, affective, and behavioral components, as conceptualized in the Framework of Inclusive Education (

Selisko et al., 2024), and are shaped by social, familial, and educational contexts. Children and adolescents acquire these attitudes through observing significant social models—such as parents, teachers, and peers—and, once formed, these attitudes tend to remain stable. Teachers’ attitudes toward the inclusion of students with disabilities are influenced by factors such as teaching experience and training, highlighting the need for ongoing professional development (

Wahsheh, 2024). These early influences reinforce themselves over time, making attitudes particularly resistant to change. Longitudinal research indicates that, especially in adolescence, negative attitudes may intensify and persist into adulthood in the absence of corrective interventions (

Álvarez-Delgado et al., 2022).

Research conducted primarily in WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) contexts consistently shows that attitudes toward people with disabilities often remain predominantly negative or reserved, even in the context of inclusive efforts. Numerous studies have found that, in the absence of awareness-raising programs, participants without prior exposure to disability issues tend to hold less favorable attitudes than expected (

Harrison et al., 2019;

Oswal et al., 2025). These negative or ambivalent perceptions are often rooted in persistent stereotypes that portray people with disabilities as in need of support or unable to contribute equally. For instance, people with disabilities are frequently stereotyped as lacking autonomy, evoking feelings of pity or even contempt among the public (

Nario-Redmond, 2020). Moreover, such stereotypes may be activated automatically, even without conscious intent to discriminate. In our study, these descriptors are treated as stereotypes, not realities, and are analyzed solely to understand their attitudinal impact.

1.2. Changing Attitudes: Intergroup Contact and Educational Interventions

A substantial body of literature suggests that attitudes can be effectively altered through structured educational interventions (

Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006;

Paluck et al., 2019). The contact hypothesis, originally developed by Allport and empirically validated in numerous studies, proposes that direct, positive interaction between members of different groups reduces prejudice, especially when supported institutionally and carried out in equal-status, cooperative contexts (

Allport, 1954;

Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). In the context of inclusive education, structured intergroup contact—such as collaborative learning in mixed groups—has proven to be one of the most effective mechanisms for reducing bias (

Paluck et al., 2019). Contact theory is widely regarded as one of the most evidence-based frameworks for combating discrimination against people with disabilities (

Paluck et al., 2019;

Boin et al., 2021).

In addition to direct interaction, interventions based on information, reflection, and active training have also shown effectiveness. A systematic review emphasizes that durable attitude change requires comprehensive, multi-faceted educational strategies (

Giuntoli et al., 2024). Effective approaches include workshops, thematic courses on disability, multimedia campaigns, personal testimonies from people with disabilities, and guided simulations followed by structured reflection. Persuasive communication strategies and group discussions that dismantle common myths about disability further contribute to attitudinal change. A Spanish study demonstrated that all three tested strategies—structured contact, role-playing, and educational debates—significantly improved students’ attitudes (

Álvarez-Delgado et al., 2022). In organizational contexts, even brief educational video clips have been found effective in reducing implicit bias and promoting inclusive attitudes (

Carvalho-Freitas & Stathi, 2017). In sum, attitudes can be transformed through controlled exposure to experiences that challenge existing stereotypes, and such interventions are crucial for creating a genuinely inclusive educational environment. However, there is a lack of rigorous experimental studies—particularly in higher education—on the use of emotionally charged media materials and the role of psychosocial variables such as tolerance and gender. Existing work has mainly focused on descriptive or correlational designs. For instance,

Carvalho-Freitas and Stathi (

2017) found that short educational videos could reduce implicit bias in organizational contexts, while

Álvarez-Delgado et al. (

2022) demonstrated that structured debates and role-playing improved student attitudes toward inclusion. Yet, few studies have systematically examined these mechanisms through controlled experimental designs.

In this context, the current study aims to investigate how the type of video message (positive, negative, neutral) influences students’ attitudes toward people with disabilities while considering individual variables such as gender and tolerance. Short emotionally charged video materials have been widely used in attitude-change research because they effectively combine affective arousal, social modeling, and narrative persuasion to foster empathy and reflection (

Braddock & Dillard, 2016;

Briñol & Petty, 2020;

Vezzali et al., 2014).

Gender has been identified as a relevant factor in shaping social attitudes, including those toward people with disabilities. Several studies have found that female students tend to express more positive attitudes and greater empathy than male students, possibly due to gender differences in socialization and emotional sensitivity (

Nowicki, 2006;

de Laat et al., 2013;

Strnadova et al., 2023;

Abed et al., 2024). In this study, the term “gender” is used rather than “sex,” as it reflects socially constructed norms and role expectations influencing perceptions and attitudes, rather than biological distinctions (

Cikara & Van Bavel, 2014;

Christov-Moore et al., 2014). Therefore, this study tests gender as an independent hypothesis in order to examine the consistency of such effects in the university context.

Employing a controlled experimental design, this research contributes to the scholarly literature by exploring the interplay of social and psychological factors in the development of inclusive attitudes. Tolerance, in this study, is conceptualized as a socio-emotional disposition reflecting openness to diversity, emotional regulation in intergroup contexts, and the rejection of prejudice. This construct captures individuals’ ability to manage discomfort and ambiguity when interacting with members of stigmatized groups (

Costantini et al., 2024).

The following research hypotheses were tested:

H1. There is a main effect of video type on attitudes toward people with disabilities, such that participants exposed to a positive video will exhibit more favorable attitudes compared to those exposed to a neutral video, while participants in the negative video condition will exhibit less favorable attitudes than those in the neutral group.

H2. There is a main effect of gender, with female participants demonstrating more positive attitudes toward people with disabilities compared to male participants.

H3. There is a main effect of tolerance level, such that participants with high levels of tolerance will report more favorable attitudes than those with low levels of tolerance.

H4. There are significant interaction effects among gender, tolerance level, and video type on attitudes toward people with disabilities.

By pursuing these objectives, the study seeks to advance current knowledge on the formation and change in attitudes toward people with disabilities and to identify effective educational interventions that support the broader goal of inclusive and sustainable education.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Variables and Research Design

The present study employed a quasi-experimental design with repeated measures, including four independent variables:

Independent Variable 1: Type of video stimulus (positive, negative, neutral—control group);

Independent Variable 2: Time of measurement (pre-test, post-test);

Independent Variable 3: Tolerance level (high, low), obtained via median split of the tolerance score;

Independent Variable 4: Participant gender (female, male).

Although the literature often refers to “gender” as a socially constructed identity, the present study operationalized gender as biological sex, based on self-identification with the binary categories “male” or “female.” No non-binary or other gender-diverse categories were included in the demographic questionnaire. This represents a limitation of the study and a direction for more inclusive future research. Consequently, all references to “gender” in this study should be interpreted in light of this binary operationalization.

The dependent variable was Attitude toward people with disabilities. In line with the social model of disability, we adopt person-first, inclusive language throughout the manuscript (e.g., “people/students with disabilities”), except when quoting sources that use identity-first terminology.

2.2. Participants

The sample consisted of 179 undergraduate students (82 male, 97 female), aged between 20 and 23 years (M = 21.4, SD = 1.6) all enrolled at the National University of Science and Technology Politehnica Bucharest. Participants were recruited via convenience sampling and randomly assigned to one of the three experimental video conditions. Inclusion criteria required participants to be undergraduate students currently enrolled in higher education, aged between 20 and 23 years, fluent in Romanian, and without self-declared disabilities (as the study focused on external attitudes toward disability). Exclusion criteria included incomplete responses to either the pre- or post-intervention assessments and failure to provide informed consent.

Information about students’ field of study was not collected as part of the demographic questionnaire. This represents a limitation of the current design, since prior research suggests that students in social sciences may exhibit more favorable attitudes toward people with disabilities, possibly due to greater exposure or prior contact (

Campbell et al., 2009). Future research should account for academic background when examining attitudinal differences.

2.3. Procedure

Ethical clarifications on stimuli. The negative video represented a widely circulating, stereotype-consistent media portrayal depicting a person with a disability as dependent; it was included solely as an object of critique to examine short-term attitudinal change. Descriptive detail was intentionally limited to reduce potential harm. The positive video highlighted agency, competence, and active social participation of a person with a disability, while the neutral video consisted of nature scenes and served as an affect-neutral baseline.

Ethical safeguards and approval. To minimize potential harm, stimulus descriptions were restricted to what was methodologically essential, and deficit-based portrayals were explicitly repudiated in an upfront Ethical Note. We recommend that future work employ ethically curated, co-designed stimuli developed in collaboration with people with disabilities and disability advocates.

The study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of the National University of Science and Technology Politehnica Bucharest (approval no. 9655/31 March 2025), as detailed in the Institutional Review Board Statement. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation. In accordance with institutional ethical standards, a waiver for data processing consent was granted, as all collected data were fully anonymized.

The study was conducted entirely online using Google Forms as the data collection platform. Participants received a personalized link via institutional email and were asked to complete all study components in a single sitting, with no time gap between the pre-test and post-test. They were informed about the objectives of the research, the voluntary nature of participation, and the anonymity and confidentiality of their responses. Participants were also notified that the video materials might contain emotionally charged content that could elicit affective responses.

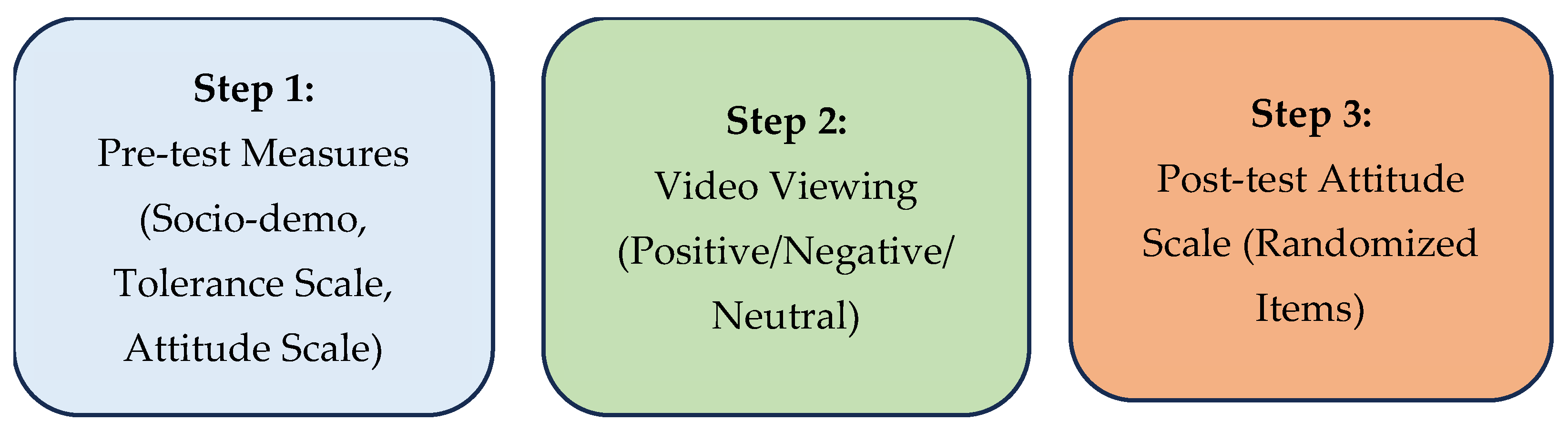

The procedure involved three consecutive steps (see

Figure 1):

- (1)

Completion of a socio-demographic questionnaire, followed by the Elementary Tolerance Scale and the initial attitude scale.

- (2)

Online viewing of one of the three video clips based on the experimental condition.

- (3)

Completion of the post-test attitude scale, in which the same items were presented in a randomized order compared to the pre-test, to mitigate response bias. The entire procedure, including both testing phases and the video stimulus, lasted approximately 10–12 min per participant.

The video stimuli, each approximately 45 s long, served as the experimental manipulation:

The positive video portrayed a person with a disability demonstrating competence and initiative by intervening to stop a robbery;

The negative video presented a widely circulating media portrayal that emphasized dependence; it is reported here solely to examine short-term attitudinal effects.

The neutral video presented scenic landscapes without human subjects.

The categorization of video stimuli as positive, negative, or neutral was based on theoretical and content-related criteria established in prior literature on media representations of disability (

Ellis & Goggin, 2015) and confirmed through researcher consensus during pilot testing. This qualitative validation ensured that emotional valence (positive vs. negative portrayal) rather than content complexity determined the classification of the clips.

The negative video reflected a commonly circulating, deficit-based media portrayal emphasizing dependency (

Ellis & Goggin, 2015); its inclusion does not indicate endorsement but enables empirical testing of how such framings may shape bias.

Figure 1.

Experimental Design Flowchart.

Figure 1.

Experimental Design Flowchart.

2.4. Data Collection, Research Instruments and Statistical Analyses

Three instruments were employed to assess the study variables: (1) a socio-demographic questionnaire; (2) the Elementary Tolerance Scale, adapted from Ellen Greenberger and reduced to 9 items (Cronbach’s α = 0.68); and (3) a 25-item scale developed for this study to measure attitudes toward people with disabilities.

The Elementary Tolerance Scale was used to assess participants’ openness toward diversity and their ability to regulate emotional responses in intergroup contexts. In the present study, tolerance was conceptualized as a socio-emotional disposition reflecting openness to diversity, emotional regulation, and rejection of prejudice. The instrument included 9 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The original English version was translated and backtranslated into Romanian by two bilingual psychologists, and semantic consistency was verified by expert consensus. Internal reliability in the present sample was acceptable (Cronbach’s α = 0.68). Although the reduced version had fewer items than the original, it retained its conceptual focus on acceptance of individual differences, cooperation, and control of negative intergroup reactions.

The second instrument, a 25-item Attitude Scale toward People with Disabilities, was developed specifically for this study. It combined strengths-based descriptors with diagnostically oriented stereotype-consistent items to capture both explicit and implicit attitudinal components. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree—5 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating more favorable attitudes. Content validity was established through expert review (three university specialists in educational and social psychology), who evaluated item clarity, relevance, and attitudinal balance. Construct validity was verified in a pilot study (N = 30), and an exploratory factor analysis confirmed a single-factor structure explaining 54.2% of total variance. Reliability was excellent (Cronbach’s α = 0.917 in the pilot and α = 0.903 in the main sample, N = 179), confirming high internal consistency.

| Reliability Statistics |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | N of Items |

| ,903 | 25 |

Prior to the main data collection, this contextualized version of the 25-item scale was also pilot tested for clarity and linguistic appropriateness. No major wording changes were required, as all items were rated as clear and relevant to the university context.

Negatively worded items were reverse-coded before computing total scores. Descriptive indices of skewness and kurtosis indicated approximately normal distributions, supporting the use of parametric analyses. Both instruments were administered online within the same session, ensuring anonymity and confidentiality. The administration took approximately 20 min.

Although the scale reflects certain deficit-based assumptions, we explicitly contextualized these items during analysis and recommend that future research adopt co-designed, affirming instruments developed in partnership with people with disabilities.

Although the instrument included a diverse set of items—ranging from cognitive evaluations (e.g., competence, barrier-related challenges) to emotional and behavioral intentions (e.g., empathy, social integration)—its structure reflects the multidimensional nature of attitudes as conceptualized in social psychology. The tripartite model of attitudes, which distinguishes between affective, cognitive, and behavioral components (

Ajzen & Fishbein, 2005), served as the theoretical foundation for item construction. This model is widely used in disability research and justified the inclusion of both positively and negatively valenced items to comprehensively capture students’ attitudinal profiles.

Importantly, stereotype-consistent or deficit-based items (e.g., assumptions of dependency or incapacity) were retained not as endorsed descriptors but as diagnostic indicators of bias. We explicitly acknowledge the ethical limitations of such items and encourage future studies to co-develop strengths-based instruments in collaboration with scholars with disabilities and advocates.

All statistical analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26). Prior to inferential testing, normality of the variables was assessed using Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. Since no significant deviations from normality were observed, parametric analyses were retained. Descriptive statistics were computed, followed by One-Way ANOVA, paired-sample t-tests, and independent-sample t-tests, depending on the hypothesis tested. Repeated-measures comparisons (paired t-tests) were applied to analyze within-subject changes between pre- and post-test scores for each video condition, while One-Way ANOVA was used to assess between-group differences across the three video types. Given that the data met normality assumptions, nonparametric alternatives such as the Friedman test were not required. Participant groups were defined a priori based on experimental conditions (video type: positive, negative, neutral) and tolerance level, determined through a median split on the Tolerance Scale. Effect sizes (η2 and Cohen’s d) were reported for all main analyses to support interpretive robustness, and all significance levels (p-values) were presented in the Results section. These analyses enabled the examination of main effects and interaction effects across variables.

Full item lists for both the Attitude Scale toward people with disabilities and the adapted Elementary Tolerance Scale are included in

Appendix A, to facilitate replication and methodological transparency.

3. Results

This section presents the outcomes of hypothesis testing, along with supplementary analyses for a deeper understanding of the relationships between variables.

Prior to hypothesis testing, descriptive statistics were examined for all study variables. Skewness and kurtosis values indicated approximate normality, and Levene’s tests confirmed homogeneity of variances across groups (p > 0.05). These results justified the use of parametric analyses in the subsequent hypothesis testing.

3.1. The Effect of Video Type on Attitudes Toward People with Disabilities (H1)

To test H1, One-Way ANOVA was conducted separately for pre-test and post-test scores. The descriptive statistics are presented in

Table 1. At pre-test, video type had a significant effect,

F(2,176) = 3.61,

p = 0.029. Participants exposed to the negative video (

M = 91.73) showed significantly more positive attitudes than those in the neutral condition (

M = 85.38). No significant differences were found between the positive video (

M = 90.88) and the other two groups.

At post-test, the effect strengthened, F(2,176) = 10.07, p < 0.001. Participants who watched the positive video (M = 93.82) scored significantly higher than those in the negative (M = 85.88) and neutral (M = 82.67) conditions.

To explore the differences between the two measurement points within each film condition, paired-sample t-tests were applied:

Positive video: significant increase, t(59) = −2.602, p = 0.012;

Negative video: significant decrease, t(55) = 5.086, p < 0.001;

Neutral video: significant decrease, t(62) = 4.305, p < 0.001.

These findings support the reinforcement effect of positive, agency-focused content and the erosive impact of stereotype-consistent or affect-neutral stimuli over time.

3.2. The Effect of Gender on Attitudes Toward People with Disabilities (H2)

To examine H2, independent- and paired-sample

t-tests were used across gender and video conditions. The detailed results by gender and video condition are presented in

Table 2.

Among men:

Positive video: significant increase, t(23) = −2.339, p = 0.028;

Negative video: significant decrease, t(29) = 4.826, p < 0.001;

Neutral video: significant decrease, t(27) = 3.277, p = 0.003.

Among women:

Positive video: no significant change, t(35) = −1.722, p = 0.094;

Negative video: significant decrease, t(25) = 2.730, p = 0.011;

Neutral video: significant decrease, t(34) = 3.075, p = 0.004.

Table 2.

Mean scores by gender and time.

Table 2.

Mean scores by gender and time.

| Gender | Pre-Test (M) | Post-Test (M) |

|---|

| Female | 88.65 | 89.57 |

| Male | 86.12 | 84.85 |

Between-group comparisons showed no gender difference at pre-test, t(177) = −1.897, p = 0.059, but a significant difference at post-test, t(177) = −2.143, p = 0.033, with females expressing more positive attitudes.

These results suggest that, over time, gender becomes a relevant factor in shaping attitudes toward people with disabilities, with women developing more favorable attitudes than men following exposure to the inclusive educational intervention.

3.3. The Effect of Tolerance on Attitudes Toward People with Disabilities (H3)

To test the hypothesis that tolerance level influences attitudes toward people with disabilities, paired-sample

t-tests were conducted separately for the high-tolerance and low-tolerance groups, based on the type of video viewed. The corresponding results are summarized in

Table 3.

For low-tolerance participants:

Positive video: no significant change, p = 0.441;

Negative video: significant decrease, p = 0.001;

Neutral video: significant decrease, p = 0.004;

For high-tolerance participants:

Positive video: no significant change, p = 0.140;

Negative video: significant decrease, p = 0.002;

Neutral video: significant decrease, p = 0.009.

Table 3.

Mean attitude scores at pre-test and post-test based on tolerance level and video condition.

Table 3.

Mean attitude scores at pre-test and post-test based on tolerance level and video condition.

| Group | Pre-Test (M) | Post-Test (M) | t(df) | p |

|---|

| High Tolerance—Positive Film | 90.00 | 92.00 | −1.518 (30) | 0.140 |

| High Tolerance—Negative Film | 102.00 | 94.99 | 3.387 (25) | 0.002 |

| High Tolerance—Neutral Film | 91.61 | 87.61 | 2.857 (22) | 0.009 |

| Low Tolerance—Positive Film | 86.00 | 89.83 | −0.789 (17) | 0.441 |

| Low Tolerance—Negative Film | 81.04 | 76.44 | 3.758 (26) | 0.001 |

| Low Tolerance—Neutral Film | 81.46 | 79.65 | 3.076 (36) | 0.004 |

Further, independent-sample t-tests revealed significant differences at both time points: Pre-test: t(160) = −5.866, p < 0.001; Post-test: t(160) = −5.457, p < 0.001.

These results support the hypothesis that a higher level of tolerance is associated with more favorable attitudes toward people with disabilities, both before and after exposure to the educational intervention promoting inclusion.

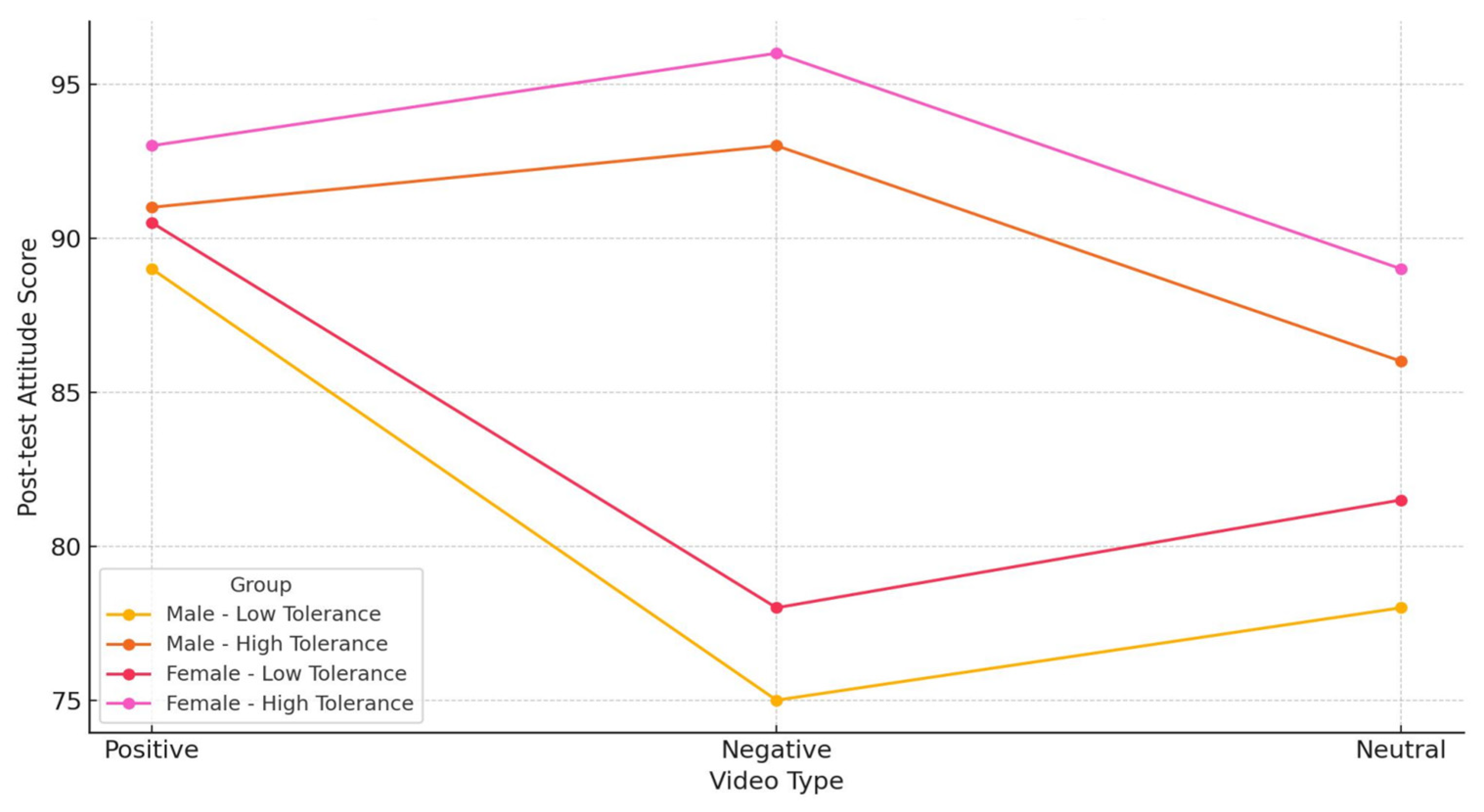

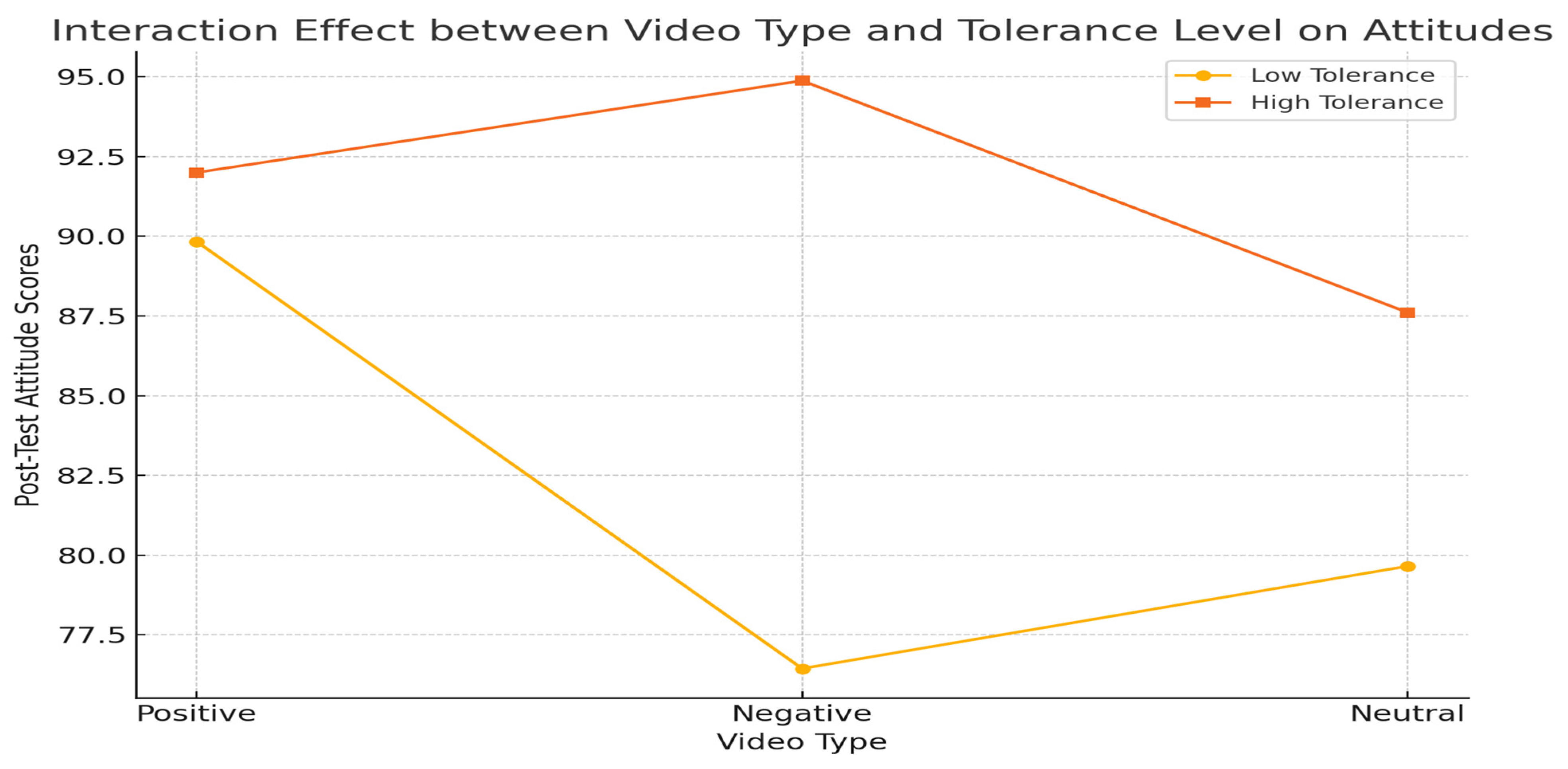

3.4. Interaction Effects Between Gender, Type of Video, and Tolerance (H4)

To test the hypothesis regarding the existence of interaction effects between participants’ gender, the type of video viewed, and tolerance level on attitudes toward people with disabilities, univariate ANOVA and independent-sample

t-tests were conducted. The results of these interaction analyses are presented in

Table 4. The interaction effect between video type and tolerance level is also illustrated in

Figure 2.

A significant interaction was found between video type and tolerance, F(2) = 3.44, p = 0.034. Among low-tolerance participants, attitudes differed significantly between the positive and negative video conditions, p = 0.012.

No significant interaction was found between gender and video type (p = 0.254) or between gender and tolerance (p = 0.120).

Although the three-way interaction between gender, video type, and tolerance level did not reach statistical significance,

Figure A1 (

Appendix A) provides a visual representation of these patterns for descriptive purposes.

These results support the notion that media-based educational interventions can have a differentiated impact depending on the participant’s psychological profile, particularly in individuals with low levels of tolerance. In this regard, recent studies (

Briñol & Petty, 2020;

Vezzali et al., 2014;

Yeager & Dweck, 2019;

Stanica et al., 2024) emphasize that emotional exposure and positive messaging are more effective in influencing individuals predisposed to bias, while already tolerant individuals may reinforce their attitudes through direct, inclusive contact and critical reflection.

It is important to acknowledge the possibility of testing effects due to the repeated administration of the same attitude scale. Although item order was randomized at post-test to minimize response bias, the short time interval between pre-test and post-test may have introduced familiarity or priming effects that could influence participants’ responses.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study provide strong evidence that affective media interventions can significantly influence students’ attitudes toward people with disabilities. Exposure to positively valenced video content led to more favorable attitudinal changes, particularly among participants with lower levels of tolerance, supporting the relevance of tailoring educational interventions to individual psychological profiles. Gender and tolerance functioned as significant moderators, with women and high-tolerance participants consistently expressing more inclusive attitudes. These findings highlight the potential of short but well-calibrated emotional interventions to produce immediate attitudinal improvements in higher education settings. However, further research is needed to assess the long-term stability of these changes.

5.1. Limitations

This study has several methodological limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the results. First, participants’ prior experience interacting with people with disabilities was not assessed—a variable known to influence attitude formation. Second, completing the questionnaires in dyads may have introduced subtle peer influences that could compromise internal validity. Third, the sample was restricted to students from a single university, limiting the generalizability of the findings to more diverse educational populations across geographic or cultural contexts.

Another important limitation concerns the ecological validity of the results. Although the online format allowed for a high degree of experimental control, it remains uncertain to what extent the observed attitudinal changes would translate into real-world behavior in face-to-face educational settings. Direct interactions often involve situational, institutional, and emotional dynamics that extend beyond the scope of an online environment. Future research should include behavioral observations or follow-up assessments in naturalistic educational contexts to enhance the ecological validity of conclusions.

A further limitation relates to the short time interval between the pre- and post-test—approximately 10–15 min, as all study components were completed in a single session—which may have influenced the magnitude and durability of the observed attitudinal changes. Although immediate post-intervention assessment, conducted directly after video exposure within the same online session, is common in experimental studies, it does not capture the long-term retention of attitudinal shifts. In this study, the intervention was operationalized as exposure to one of three 45 s video clips (positive, negative, or neutral) depicting distinct portrayals of disability. Future research should incorporate delayed post-tests or longitudinal designs to assess the persistence and real-world applicability of attitudinal change. Additionally, a content-related limitation arises from the partial overlap between the video stimuli and certain items in the attitude scale (e.g., items that framed people with disabilities as dependent or incapable). Although the scale was pre-validated and demonstrated strong internal consistency, this alignment may have introduced demand characteristics or priming effects, whereby participants’ responses were directly shaped by the narrative content. Although the scale reflects certain deficit-based assumptions, we explicitly contextualized these items during analysis and recommend that future research adopt co-designed, affirming instruments developed together with people with disabilities.

Future studies should aim for a clearer conceptual separation between stimulus materials and outcome measures, potentially through the use of indirect or implicit instruments. Moreover, the high Cronbach’s alpha reported for the attitude scale, although indicative of strong internal consistency, must be interpreted with caution. It is well established that alpha values can be artificially inflated by the number of items included in a scale, regardless of their conceptual coherence. Future research should consider complementing internal consistency indices with additional validation metrics such as confirmatory factor analysis, item–total correlations, or McDonald’s omega to ensure robust measurement integrity.

Finally, the potential influence of social desirability bias must be acknowledged. Given that some items in the attitude scale were formulated in a deliberately provocative manner (e.g., “statements reflecting stereotypes”) to measure implicit negative attitudes, participants may have altered their responses to align with socially acceptable views, especially in a university setting. This response distortion could lead to an underestimation of explicit negative attitudes. Future research could incorporate social desirability scales or use indirect measurement techniques to control for this effect.

Furthermore, several ethical limitations should be acknowledged. Participants were informed that the video materials might include emotionally charged content that could evoke affective responses. After completing the post-test, all participants received a written debriefing note explaining the purpose of the study, the rationale for using contrasting video materials, and contact information for psychological support services available through the university. This step aimed to mitigate potential distress and enhance ethical transparency. However, no formal debriefing session was conducted, which is acknowledged as a limitation of the study. Additionally, individuals with disabilities were not directly involved in the design or review of the video materials, raising concerns regarding inclusivity and representational authenticity. Future research should co-create such materials in collaboration with members of the disability community to ensure cultural, social, and emotional appropriateness. Taken together, these limitations warrant cautious interpretation and motivate ethically co-designed replications in naturalistic educational settings, with delayed post-tests and measurement strategies that minimize stimulus–item proximity.

5.2. Future Research Directions

Building on these findings, future studies should further explore the psychosocial mechanisms that influence attitude change toward people with disabilities, particularly in real-world educational environments. Longitudinal designs are recommended to assess the durability of media-based intervention effects and their transferability to authentic learning contexts. Educational interventions should be adapted based on participants’ attitudinal profiles and levels of tolerance, allowing for more efficient personalization of affective content. As suggested by recent literature on the role of individual differences in message processing (

Cikara & Van Bavel, 2014) tailoring interventions to psychological traits may improve their efficacy. The implementation of personalized media micro-interventions, grounded in participants’ tolerance levels or other psychosocial characteristics, could enhance the impact of educational campaigns. Future research should also emphasize participatory and co-designed methodologies, involving people with disabilities as active collaborators in the development of intervention materials, to ensure authenticity, dignity, and representational fairness.

These interventions should be embedded in structured programs that include guided reflection, group discussion, and formative feedback to support the internalization of inclusive values. Additionally, future research should incorporate behavioral or observational assessment methods to correlate expressed attitudes with actual inclusive behaviors in university settings. Methodological triangulation that combines explicit scales, implicit measures, and qualitative insights will reduce the risk of stereotype priming and strengthen ecological validity.

5.3. Implications for Educational Practice

The results support the development of differentiated educational interventions tailored to students’ psychological characteristics. Key recommendations include the use of video-based micro-interventions featuring authentic and affirming emotional narratives that highlight agency, competence, and social participation of people with disabilities, to foster identification and empathy (particularly for students with low tolerance).

In addition, the organization of applied empathy labs—incorporating VR simulations and guided contact with people with disabilities as co-facilitators—can reinforce prosocial attitudes (especially among high-tolerance groups). Such labs should be designed not only to challenge stereotypes but also to cultivate respect, dignity, and recognition of diversity as a civic value.

Teacher education and faculty development programs should embed inclusive pedagogy modules co-created with disability advocates and students with lived experience, ensuring that inclusion is not only taught but also modeled. By grounding interventions in participatory practices, educational systems can move beyond awareness-raising toward the cultivation of lasting inclusive cultures that value difference as a source of collective strength.

5.4. Implications for Public Policy

We recommend the development of intelligent educational platforms that incorporate psychological profiling algorithms capable of directing users to content adapted to their tolerance levels and information processing styles. However, we caution that such platforms must be designed with fairness and inclusiveness in mind. Recent studies highlight that algorithmic decision-making in educational contexts may reproduce or amplify social biases, particularly against people with disabilities. Bias can arise from non-representative training data, flawed design assumptions, or lack of interpretability mechanisms. If unaddressed, these issues risk undermining the equity goals of inclusive education (

Baker & Hawn, 2022;

Chinta et al., 2024;

Holstein et al., 2019). Ensuring algorithmic transparency, fairness, and disability-inclusive datasets is therefore critical for responsible AI integration in education.

In parallel, public awareness campaigns should rely on empirically validated, strengths-based narratives co-developed with people with disabilities, disseminated via high-impact media channels to promote societal-level attitude change. Special attention should also be directed toward teacher training and preparation (

Neagu, 2019). Teacher training policies remain central to advancing inclusive practices and sustainability in higher education (

Nicoleta, 2013).

In terms of concrete policy and curricular recommendations, we suggest integrating structured empathy development modules into teacher education programs, mandating inclusive pedagogy training as part of national accreditation standards, and revising university curricula to include disability studies as a cross-disciplinary field rooted in social justice and human rights. Additionally, ministries of education could implement periodic attitude assessments among students and faculty as part of institutional quality assurance frameworks, ensuring that people with disabilities are meaningfully involved in the design, monitoring, and evaluation of such initiatives.

5.5. Final Remarks

This study contributes to the growing body of research on inclusive education by demonstrating that emotional media interventions, when tailored to individual psychological characteristics such as tolerance and gender, can meaningfully influence attitudes toward people with disabilities in higher education. By integrating affective narrative content with experimental design and validated measurement tools, the research highlights both the potential and the complexity of attitude change mechanisms in young adults. Importantly, the study also underscores the need to critically reflect on the language and tools employed in disability research. Future work must ensure that research instruments and intervention materials avoid deficit-based framings and instead highlight the agency, dignity, and lived expertise of people with disabilities.

While the findings underscore the importance of personalized educational strategies, they also call for broader institutional and policy-level actions to ensure the sustainability and scalability of inclusive practices. These conclusions align with Goal 4 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which emphasizes inclusive, equitable, and quality education for all, and highlight the need for educational systems to address attitudinal and structural barriers affecting people with disabilities.

By centering strengths-based narratives and ensuring the co-creation of educational initiatives with people with disabilities, future research and practice can move beyond awareness-raising to the cultivation of genuinely inclusive academic environments. These environments do not merely accommodate diversity but actively embrace it as a foundation of social sustainability and democratic resilience.