Abstract

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic uniquely challenged non-formal education (NFE), a sector reliant on interpersonal engagement, by forcing a rapid shift to remote work. This study examines how managerial leadership styles, technological self-efficacy (TSE), and attitudes toward remote work intersect among NFE coordinators in Israel’s Arab society, a minority community facing distinct cultural and systemic challenges. Aim: Focusing on school-based social-community education coordinators (SCECs) and community-based non-formal education coordinators (NFECs), the study investigates how leadership and organizational context shaped their adaptation to crisis. Method: The study employed a cross-sectional survey design, with data collected from 132 coordinators and 47 youth department directors between June and October 2021 using validated questionnaires. Pearson correlations, moderated mediation analysis, and ANOVA were used to analyze the data. Findings: The results revealed positive correlations between transformational leadership style (TLS), TSE, job satisfaction, and positive attitudes toward remote work. Critically, the analysis uncovered a context-dependent mechanism: TSE fully mediated the relationship between TLS and attitudes toward remote work, but this effect was significant only for community-based NFECs, not for school-based SCECs. Additionally, SCECs reported higher satisfaction and TSE than NFECs, who perceived more laissez-faire leadership. Contributions: Drawing on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory, the findings underscore that leadership’s effectiveness in crises is not one-size-fits-all; its impact is channeled through different mechanisms depending on the organizational ecosystem. The study highlights the pivotal roles of adaptive leadership and TSE in sustaining resilient NFE in minority communities. Theoretical and practical implications point to the need for culturally responsive, context-sensitive leadership development and targeted technology training to foster equitable learning environments.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic caused unprecedented disruptions to educational systems worldwide, prompting a swift shift to remote work and digital platforms (Al Attar et al., 2023; Masry-Herzallah & Dor-Haim, 2024). This transition significantly heightened stress among educators, impacting their well-being as they navigated new sources of pressure and adapted to the absence of direct leadership typical in face-to-face teaching (MacIntyre et al., 2020; Da’as et al., 2023). In the context of minority communities such as Israel’s Arab society, this shift was particularly challenging for non-formal education (NFE), as it exacerbated existing inequalities and cultural tensions (Goldratt et al., 2023; Masry-Herzallah et al., 2025).

NFE plays a vital role in promoting social cohesion and youth development within these communities (Hadad Haj-Yahya et al., 2021; Jaraisy & Agbaria, 2023; Masry-Herzallah, 2023a). However, the abrupt pivot to remote operations challenged the very essence of NFE’s hands-on, community-centric model, making effective crisis management a paramount concern for educational leaders, who were tasked with ensuring the “holistic safety” physical, social, and psychological of their staff (Peltola et al., 2024). Therefore, understanding how leadership and technological factors, such as technological self-efficacy (TSE), influence educators’ adaptability and resilience during crises is critical. TSE, defined as an individual’s confidence in their ability to perform tasks effectively (Bandura, 2006), emerged as a significant factor alongside managerial leadership styles during the pandemic (Harris, 2020; Masry-Herzallah, 2023b; Apaydın & Yalçın, 2024).

This study explores the relationship between managerial leadership styles, TSE, and attitudes toward remote work among NFE coordinators in Israel’s Arab society. It focuses on two primary groups: social-community education coordinators (SCECs) within schools and non-formal education coordinators (NFECs) in youth departments. While SCECs oversee NFE programs in the formal school system, NFECs manage community-based activities. Both groups work with youth in similar age ranges (Masry-Herzallah et al., 2025; Masry-Herzallah, 2023a).

This study utilizes Bass’s (1985) Full Range Leadership model and Bandura’s (2006) self-efficacy theory to examine how transformational leadership style (TLS) behaviors affect coordinators’ TSE and attitudes. Research consistently demonstrates that TLS enhances positive attitudes and performance in NFE settings (Lindsey et al., 2019; Soles et al., 2020). Moreover, Al Attar et al. (2023) found a strong connection between participative leadership—a key element of TLS—and teachers’ well-being during the COVID-19 crisis. Recent studies further confirm the crucial role of TLS in fostering positive behaviors and affective commitment among educators (Mell & Somech, 2023; Sheffer, 2023; Masry-Herzallah, 2023b).

This study also examines how institutional support and resources differ between NFECs and SCECs, which is in line with transformative learning principles (Nissilä et al., 2022). The unique cultural values and social structures of Israel’s Arab society highlight the need for an ecological systems perspective (Serhan, 2023). The Arab education system faces multiple challenges, such as lower funding and limited infrastructure (Masry-Herzallah & Stavissky, 2021). Arab culture tends to be more collectivist and hierarchical, shaping leadership expectations (Masry-Herzallah & Dor-Haim, 2024; Tannous, 2022).

While recent systematic reviews have mapped the extensive challenges faced by educational leaders during the crisis (e.g., Chatzipanagiotou & Katsarou, 2023), a significant research gap persists in understanding the underlying mechanisms through which leadership influenced outcomes in the under-researched NFE sector. The literature often discusses leadership and technology as separate domains, yet the pandemic forced their convergence into “digital crisis leadership.” It remains unclear how established models like TLS function when mediated by educators’ TSE and whether this mechanism is moderated by the unique organizational contexts of SCECs versus NFECs. This study addresses this gap by examining the interplay between leadership, technology, and context in NFE during a period of profound disruption.

By investigating these dynamics, this research contributes to the growing body of knowledge on inclusive education, offering strategies to foster resilient and equitable NFE environments. The results can inform targeted interventions that bridge digital divides and cultivate adaptive leadership. To achieve these objectives, the research formulates the following questions:

- How do managerial leadership styles relate to SCECs’ and NFECs’ job satisfaction and attitudes toward remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Does TSE mediate the relationship between TLS and coordinators’ attitudes toward remote work?

- Are there significant differences in the perceptions and experiences of SCECs compared to NFECs regarding leadership styles and technological adaptation?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptualizing Non-Formal Education as an Ecological System

NFE, rooted in experiential learning beyond the confines of traditional classrooms, is characterized by voluntary participation, flexibility, and responsiveness to learners’ needs (Bakioglu et al., 2018; Romi & Schmida, 2009). La Belle (1981) positioned NFE within a “tripartite educational system” alongside formal and informal learning, arguing that all learning experiences throughout life are interconnected and mutually influential. This conceptualization, while foundational, has been critiqued for potentially oversimplifying the fluid boundaries between educational modalities (Rogers, 2019). More recent scholarship emphasizes NFE as existing on a continuum rather than as a discrete category, acknowledging that the same activity may serve different functions depending on context and intentionality (Cohen, 2001; Ahmed, 2023). Recent research has found that teachers were among the most negatively impacted employees during the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of job-related well-being (Davidsen & Petersen, 2021), highlighting the importance of understanding these ecological factors in the context of NFE.

This systemic view aligns with Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems theory, which examines human development through the lens of nested environmental contexts: The microsystem encompasses an individual’s immediate settings and relationships (in this study, SCECs and NFECs); the mesosystem involves interactions between microsystems (e.g., coordinators and managers); the exosystem comprises indirect influences from social structures (e.g., educational policies); the macrosystem reflects overarching cultural values, norms, and laws; and the chronosystem represents temporal changes and sociohistorical events (e.g., the COVID-19 crisis). While Bronfenbrenner’s framework has been extensively applied to formal education contexts, its application to NFE remains undertheorized, particularly regarding how the voluntary and flexible nature of NFE creates distinct microsystem dynamics compared to compulsory schooling (Simac et al., 2021). Moreover, in post-conflict or marginalized community settings, the ecological systems may exhibit atypical configurations where exosystem and macrosystem factors exert disproportionate influence on microsystem functioning (Van der Linden, 2015).

This ecological framework provides a valuable lens for understanding how SCECs and NFECs experienced the shift to remote work during the pandemic, recognizing the interplay of individual, organizational, sociocultural, and temporal factors (El-Batri et al., 2019; Gudek, 2019). However, a critical gap exists in the literature regarding how rapid chronosystem disruptions such as pandemic-induced lockdowns interact with pre-existing macrosystem inequalities to produce differential outcomes across organizational contexts within the same educational sector (Masry-Herzallah & Dor-Haim, 2024).

2.2. Social-Community Education and Non-Formal Education in Arab Society in Israel

Few studies address social-community education and NFE within Arab society in Israel, underscoring the significance of this research as a valuable addition to the existing body of knowledge. The scarcity of research on NFE in Arab society in Israel stands in stark contrast to the growing international literature on NFE in minority and marginalized communities (Hussien Sayed Abdelhamid, 2024), revealing a significant knowledge gap regarding how NFE functions within internal minority contexts in democratic states with protracted intergroup conflicts.

Israel has an estimated population of 9.6 million, comprising 73.6% Jewish, 21.1% Arab, and 5.3% other groups (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2022). Arabs are predominantly Muslim (82.9%), with Christian (7.9%) and Druze (9.2%) minorities. Israel’s education system includes Jewish state secular and religious schools, along with segregated Arab schools (Levy, 2023; Sion, 2014). However, Arab schools face systemic disadvantages compared to Jewish schools, including lower budgets, inferior infrastructure, and less comprehensive curricula. These structural disparities reflect broader patterns documented internationally, where minority educational systems within majority-dominated states experience resource marginalization (Blaak et al., 2013). Yet, the Israeli-Palestinian case presents unique complexities due to the intersection of ethnic-national conflict, contested citizenship, and divergent collective narratives, factors that fundamentally shape the sociopolitical context in which NFE operates (Jaraisy & Agbaria, 2023).

Israeli Arab culture is often described as traditional and collectivistic (Herbst-Debby et al., 2022) with high power distance, contrasting with the individualism and low power distance associated with Israeli Jewish culture (Masry-Herzallah, 2023b; Hofstede, 1981). However, this characterization has been challenged as potentially essentializing and failing to account for internal diversity, generational shifts, and the agency of Arab-Palestinian youth in negotiating hybrid identities (Masry-Herzallah & Cohen, 2024; Tannous, 2022). Contemporary research on minority youth development emphasizes the dynamic process of “dual integration” (Berry, 2019), wherein individuals seek to maintain cultural identity while participating in wider society—a process that NFE can either facilitate or complicate depending on program design and implementation (Masry-Herzallah, 2023b).

In Israel, including within Arab society, social-community education falls under the purview of the Social and Youth Administration in the Ministry of Education. This body oversees the development of content and educational programs centered on social values. It provides a plethora of resources and activities for both regular periods and during the COVID-19 crisis. Additionally, it manages the professional development of SCECs in post-primary schools (Goldratt et al., 2023). In contrast, NFE outside of schools, such as in the youth departments of local authorities, only commenced operations in 2011. It is governed by the “Local Authorities Law” (the Director of the Youth Unit and Student and Youth Council). According to this legislation, the youth department’s director, who reports directly to the local authority, is tasked with advancing NFE within the local education authority (Mandel-Levy & Artzi, 2016). This bifurcated governance structure creates fundamentally different organizational ecosystems that may differentially buffer or amplify the effects of external shocks such as the COVID-19 crisis (Peltola et al., 2024).

Research highlights several conceptual challenges facing NFE in Arab society. Its foundation in a postmodern Western theoretical perspective, rooted in humanistic ethics and neoliberal state worldviews, contrasts sharply with the traditional collective ethos that underpins Arab society’s legitimacy (Tannous, 2022). This tension mirrors broader debates in international NFE scholarship regarding the cultural appropriateness of transferring Western-derived educational models to non-Western contexts (Novrita et al., 2025; Rogers, 2019). Studies from Indonesia, for instance, demonstrate that grassroots NFE initiatives thrive when they integrate local cultural elements and build sustainable partnerships (Novrita et al., 2025), suggesting that cultural adaptation may be more critical than previously recognized in determining NFE effectiveness. Additional obstacles include the availability of skilled personnel, the scope and quality of activities, and access to physical infrastructure (Serhan, 2023). In line with the macro-ecological model, these challenges potentially influence the satisfaction and attitudes of SCECs and NFECs, especially considering the intensified difficulties during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As the shift to remote work began, recent findings suggest that youth departments in Arab society were ill-equipped for this transition across macro, meso, and micro levels. Factors such as inadequate technological infrastructure, a limited range of activities in Arabic, and a shortage of staff trained in both NFE and information and communications technology (ICT) impacted the TSE of coordinators. This competence is essential for effective work during the crisis (Weisblai, 2020). These digital divides reflect patterns documented in international research on minority communities’ access to digital resources during COVID-19 (Howard et al., 2021), though the specific intersection of linguistic marginalization, infrastructural deficits, and professional training gaps in the Arab sector presents a unique configuration of barriers. Conversely, social-community education is shaped by various factors at the macro and meso levels. At the macro level, it benefits from guidance and support from counselors and supervisors and a digital activity database provided by the Social and Youth Administration. At the meso level, SCECs, who are primarily subject teachers, also champion social-community education in schools. Concerning ICT training, SCECs require it to enhance formal education. Additionally, school infrastructure and the adoption of online learning in traditional education have an impact on the micro level, which is visible in the coordinators’ TSE. Consequently, this study seeks to discern the differences between social-community education and NFE within the Arab sector’s youth departments.

2.3. The Effectiveness of Leadership Styles in Formal and Non-Formal Education

The full-range leadership model stands as one of the most recognized theories in educational administration (Hallinger, 2014). This theory delineates three leadership styles: laissez-faire, transactional, and TLS. Laissez-faire leaders often avoid interactions with their subordinates and shirk their responsibilities, leading to perceptions of a “leadership void” (Yukl, 2012). Transactional behaviors, more instrumental than TLS ones, typically revolve around task orientation or exchanges between the leader and their subordinates (Avolio et al., 2009). Leaders are primarily motivated by the allure of expected rewards or the fear of potential penalties (Bass & Avolio, 1994). In contrast, TLS extends beyond mere economic exchanges based on rewards and punishments. It encompasses emotional and social exchanges, characterized by five distinct traits:

- Intellectual stimulation: The leader challenges and takes risks, embracing the ideas of those they lead.

- Individual Consideration: The leader attends to the individual needs of their subordinates, acting as a mentor or coach, demonstrating empathy and active listening.

- Inspirational Motivation: The leader articulates a vision, sets high standards, and fosters optimism about future achievements while providing present task significance.

- Idealized Influence: The leader engages meaningfully with each subordinate, influencing their perspectives.

- Charismatic Attribution: The leader is revered by their subordinates due to their attitudes and the positive sentiments they inspire (Bass & Avolio, 1994).

While the full-range leadership model enjoys widespread acceptance, recent studies have identified important limitations and contextual contingencies. Meta-analytic evidence suggests that the discriminant validity between transformational and transactional leadership dimensions may be weaker than originally theorized (Judge & Piccolo, 2004), raising questions about whether these truly represent distinct leadership approaches or different facets of effective leadership more broadly. Furthermore, cross-cultural research reveals that the effectiveness of specific TLS behaviors varies significantly across cultural contexts, with collectivist cultures potentially responding differently to individualized consideration than individualist cultures (Hofstede, 1981; Masry-Herzallah & Stavissky, 2023).

Research suggests that both TLS and transactional leadership can be pivotal during crises (Bass & Bass, 2009; Boehm et al., 2010). Some studies even posit that TLS outperforms transactional leadership in crisis situations (Waldman et al., 2001). However, this conclusion is not universal; some recent investigations suggest that during acute crises characterized by high uncertainty and urgency, elements of transactional leadership, particularly contingent reward and active management, may be more immediately effective in ensuring task completion, while TLS becomes more salient during recovery and adaptation phases (Lenz et al., 2023; Apaydın & Yalçın, 2024). This temporal dimension of leadership effectiveness remains underexplored in educational contexts. The success and growth of an organization often hinge on the efficacy of its leadership style (Al Attar et al., 2023; Nissilä et al., 2022; Shafaei et al., 2023; Widodo et al., 2017). TLS is believed to foster flexible thinking, innovation, and organizational creativity (Jung et al., 2003; Mumford et al., 2002). Hence, a leadership style that promotes cognitive flexibility is crucial for advancing NFE, which inherently values flexibility and champions cognitive adaptability in its leaders (Cohen, 2001). Recent studies further demonstrate that TLS facilitates the development of self-efficacy across domains (Burić et al., 2021; Masry-Herzallah et al., 2025), though the mechanisms through which this occurs—whether through modeling, verbal persuasion, or mastery experiences remain contested. TLS plays a vital role in nurturing a tech-savvy workforce, driving innovation, and endorsing culturally sensitive educational practices (Masry-Herzallah et al., 2025; Netithanakul, 2017).

From the perspective of ecological theory, research underscores a symbiotic relationship between social, cultural, and political contexts and the managerial roles and practices within Arab society in Israel. Arab society managers tend to exhibit more authoritarian tendencies, with pronounced power distances between them and their employees (Masry-Herzallah & Stavissky, 2023; Tannous, 2022). This stands in stark contrast to the liberal, democratic ideals that underpin NFE.

This contradiction illuminates a broader tension in NFE implementation within minority communities: the potential misalignment between the participatory, democratic ethos of NFE as theorized in Western scholarship (Freire, 1970; Rogers, 2019) and the hierarchical organizational cultures that may characterize minority institutions shaped by traditional collectivist values (Kress, 2006). International comparative research suggests that NFE programs are most sustainable when leadership practices are culturally congruent while still maintaining the participatory core of NFE pedagogy (Novrita et al., 2025; Van der Linden, 2015).

It’s noteworthy that no existing research specifically addresses directors of youth departments within Arab society. These directors and their staff possess a distinct commitment system. Besides their organizational and professional obligations, they are politically aligned with the head of their authority (Drory & Vigoda-Gadot, 2010). Policy reports examining NFE in Arab society have highlighted that a significant number of youth department directors and functionaries, such as coordinators, lack formal academic training in NFE (Hadad Haj-Yahya et al., 2021; Masry-Herzallah, 2023a). This scenario likely influences the perceptions of NFECs regarding the leadership styles of youth department directors in Arab society in Israel.

2.4. Leadership Styles in the Wake of the COVID-19 Crisis

The role of managers has expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic (Lenz et al., 2023). They now serve as intermediaries between district policies, local authorities, school activities, and NFE organizations (Da’as et al., 2023; Masry-Herzallah et al., 2025). Additionally, they must be attuned to how staff navigate this transition (Goldratt et al., 2023). The pandemic transformed educational leadership from primarily instructional and administrative functions to encompass crisis management, mental health support, and technological facilitation multidimensional role expansion for which most leaders were inadequately prepared (Peltola et al., 2024; Chatzipanagiotou & Katsarou, 2023). Establishing an organizational culture that emphasizes mentorship and support is a crucial aspect of a director’s role.

Recent research highlights the effectiveness of TLS in crisis management. TLS has proven beneficial in enhancing self-efficacy and organizational performance (Burić et al., 2021), as well as fostering successful online learning (Harris, 2020; Masry-Herzallah, 2023b). Leaders employing TLS lead by example, empower and collaborate remotely, and utilize effective communication to ensure positive outcomes for all (Harris & Jones, 2020). Al Attar et al. (2023) found that participative leadership had the strongest positive relationship with teachers’ well-being during the COVID-19 crisis in UAE public schools, further emphasizing the importance of leadership styles in educational settings during crises. However, it is important to note methodological limitations in this emerging literature: most studies employ cross-sectional designs that cannot establish causality, and few have examined whether leadership effects during crises differ from those in stable periods or whether they represent amplifications of existing relationships rather than qualitatively distinct phenomena (MacIntyre et al., 2020). Furthermore, the extent to which findings from formal education generalize to NFE with its distinct organizational structures, voluntary participation, and community-based operations remains empirically underexplored (Hayati & Idin, 2024).

Emerging scholarship on “digital crisis leadership” suggests that the pandemic necessitated not merely the application of existing leadership competencies to new modalities, but rather the development of fundamentally new leadership capacities integrating technological fluency, distributed coordination, and digital emotional intelligence (Savitri & Sudarsyah, 2021; Mell & Somech, 2023). This integration challenge may have been particularly acute in contexts where pre-existing digital infrastructure and TSE were limited (Oyedotun, 2020).

Taken together, this literature review establishes a clear conceptual pathway. TLS emerges as a particularly potent style during crises, capable of fostering motivation and flexibility. Simultaneously, TSE has become a critical psychological resource, mediating how educators adapt to new technological demands like remote work. The unique context of NFE, characterized by its organizational diversity and community-facing roles, combined with the specific cultural and systemic challenges within Israel’s Arab society, creates a complex ecosystem. It is at the intersection of these three domains—leadership, technology, and context—that this study seeks to make its contribution. The following hypotheses are formulated to test these proposed relationships.

Based on the synthesized literature, this study hypothesizes the following:

H1.

A manager’s TLS will be more positively associated with coordinators’ job satisfaction and attitudes toward remote work compared to transactional and laissez-faire leadership styles.

2.5. Transformational Leadership Style and Technological Self-Efficacy: Moderated Mediation Relationship

Within the framework of ecological theory, individuals continuously interact with their goals, beliefs, and emotions, which in turn guide their actions. This article specifically focuses on the TSE of SCECs and NFECs, as it’s a pivotal factor for promoting work during the COVID-19 era. This emphasis stems from the concept of self-efficacy (Bandura, 2006), which represents an individual’s confidence in their ability to achieve in various domains and execute tasks effectively (Koc & Bakir, 2010).

The rise of information and communication technology (ICT) has reshaped learning patterns across formal, informal, and NFE. In this evolving landscape, educators must embrace innovative learning technologies (Omar & Ismail, 2020). The capability of educators to craft pedagogies based on cutting-edge technology is indicative of high self-efficacy in technology (Crossan, 2020).

The shift to remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated that SCECs and NFECs heavily rely on ICT to facilitate communication and activities with students. To excel in this environment, technological readiness and competence hinge not just on personal attributes but also on institutional support (Howard et al., 2021; Oyedotun, 2020). The profound influence of requirements and resources on both the microsystem and the broader ecosystem, combined with their collective impact on the ability of SCECs and NFECs to enhance TSE, attitudes, and satisfaction, cannot be overlooked. Leadership style, particularly TLS, plays a pivotal role in this dynamic. Research indicates that TLS boosts leaders’ intrinsic motivation (Judge & Piccolo, 2004), which in turn elevates their TSE (Mao et al., 2019) and overall performance (Lai et al., 2020). By facilitating professional development, training, and support for educational staff, TLS can enhance their TSE (Chang et al., 2021), which subsequently impacts their performance (Savitri & Sudarsyah, 2021). Thus, a TLS manager who fosters the TSE of coordinators can positively influence their attitudes towards remote work in the COVID era. This study further hypothesizes the following:

H2.

TSE mediates the relationship between TLS and the attitudes of SCECs and NFECs.

This study posits that when comparing SCECs and NFECs, the positive effects of TLS on TSE, satisfaction, and attitudes are more pronounced for NFECs than for SCECs. A potential reason might be the limited availability of activities in Arabic and the inadequate techno-pedagogical training for professionals and coordinators in youth departments during COVID-19 (Rosner, 2020; Weisblai, 2020). Conversely, the satisfaction of SCECs is influenced at the macro, meso, and micro levels, as previously discussed. This encompasses guidance from instructors, access to remote learning activity repositories, support from ICT coordinators, and techno-pedagogical training. Therefore, another hypothesis of this study is as follows:

H3.

NFECs will report lower satisfaction levels compared to SCECs.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

This study employed a quantitative research design using survey methodology to explore the relationships between leadership styles, technological competence, and work attitudes among non-formal education coordinators.

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

The sample was composed of 132 Arab coordinators in Israel: 85 SCE coordinators in secondary schools and 47 NFE coordinators working in Arab local government youth departments. (These coordinators were chosen out of a total of 320 SCE coordinators in Arab society and between 300 and 350 NFE coordinators in the local government youth departments.) Directors of youth departments also participated, with 47 out of 65 directors responding, saying they had managerial perspectives in this context. Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of the sample by role.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the research participants by role.

3.3. Measures

Several validated instruments were employed, and their choice was substantiated by previous reliability scores and adaptations for cultural relevance. The tools are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Research instruments and descriptions.

Prior to the full implementation of the research, a pilot study was conducted to assess the psychometric properties of the scales used in the survey. This preliminary phase involved a sample of 20 NFE, equally divided between SCECs and NFECs from Arab society. The aim of the pilot study was to ensure the reliability and validity of the questionnaire instruments in capturing the nuances of managerial leadership styles, TSE, and attitudes toward remote work.

3.4. Procedure

The questionnaire was administered using Google Forms from June 2021 to October 2021, following approval from the institutional ethics committee in early June 2021 (Approval No.: N:062021). The main questionnaire was circulated among NFECs and SCECs across Arab society in Israel. In August 2021, a specialized version targeting directors of youth departments, which focused on leadership style, job satisfaction, and TSE, was also distributed and collected through the end of October. At the start of the Google Form, participants viewed an electronic informed-consent page. The first mandatory item asked “Do you consent to participate in this research?” Only respondents who selected “Yes, I consent” could proceed; if “No” was selected (or the form was exited), the survey terminated and no data were recorded. No responses with a “No” selection were collected.

Our sampling approach incorporated both probabilistic and non-probabilistic methods. Initially, coordinators and managers were identified via a random selection of five instructors who specialize in non-formal and social education within Arab society. This was followed by a snowball sampling technique, as outlined by Bryman (2016), where initial respondents recommended further participants. This method proved essential in reaching coordinators and managers who might be inaccessible through traditional sampling methods. Additionally, to broaden the participant base, convenience sampling was employed by directly emailing the questionnaire to potential respondents and distributing it through specific WhatsApp groups frequented by the target audience.

To counteract potential biases inherent in snowball sampling, such as network homogeneity, deliberate efforts were made to include participants from a wide range of geographical locations, organizational types, and demographic backgrounds. Participants were thoroughly briefed on the study’s objectives, and the researcher’s contact information was provided to foster transparency. Informed consent was obtained electronically before any survey items were displayed; participation was voluntary and anonymous, no direct identifying information was collected, and results are reported in aggregate/de-identified form. All procedures adhered to institutional and national standards and to the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

It is important to note that the first and second authors are members of Arab society, while the third author is from Jewish society. All three researchers have an excellent understanding of the NFE sector within Arab society. This cultural insight is a significant strength of the study, as it enabled a more nuanced and contextually relevant approach to participant selection and data interpretation. While the combination of probabilistic and non-probabilistic sampling methods might introduce certain biases, the researchers’ deep familiarity with the cultural and educational contexts under analysis helps to mitigate these concerns and enhances the validity of the findings.

3.5. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS Version 27.0. To address RQ1 (how managerial leadership styles relate to SCECs’ and NFECs’ job satisfaction and attitudes toward remote work), we used descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations to provide an overview of the variables and to examine associations among leadership styles, TLS, TSE, job satisfaction, and attitudes. To test RQ2 (whether TSE mediates the relationship between TLS and coordinators’ attitudes toward remote work), we conducted a moderated mediation analysis using SPSS’s PROCESS macro (Model 7; Hayes, 2018). This model estimated the indirect effects of TLS on attitudes via TSE, with subordination to the school principal (coded as 1 = SCEC, 0 = NFEC) as the moderating variable, while controlling for age, seniority, and school proactiveness. The PROCESS macro is particularly suited for such models, as it allows simultaneous estimation of direct, indirect, and moderated effects. To address RQ3 (differences between SCECs and NFECs in leadership styles and technological adaptation) and RQ4 (comparisons between NFECs and youth department directors), we conducted one-way ANOVAs with post hoc tests to identify significant group differences across job satisfaction, leadership styles, and TSE.

4. Results

RQ1: How do managerial leadership styles relate to SCECs’ and NFECs’ job satisfaction and attitudes toward remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic?

As is customary in social sciences research, we begin with descriptive statistics, including correlations among the study variables. Presenting correlations among the three leadership styles (transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire) provides an overview of their interrelationships and allows readers to compare the pattern of associations with prior work in this field.

Table 3 presents descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations for the coordinators-only sample (n = 132). Attitudes toward remote work showed the strongest association with TSE (TSE; r = 0.63, p < 0.01), indicating that coordinators who felt more efficacious with technology were also more open to remote work. Attitudes were also positively related to job satisfaction (r = 0.39, p < 0.01), TLS (TLS; r = 0.35, p < 0.01), and transactional leadership (r = 0.26, p < 0.01), whereas the association with laissez-faire leadership was not significant (r = −0.09, ns).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics & correlations between research variables.

Job satisfaction itself was robustly linked to leadership and technology-related perceptions: higher satisfaction coincided with higher TLS (r = 0.52, p < 0.01), higher transactional leadership (r = 0.30, p < 0.01), and higher TSE (r = 0.46, p < 0.01), and with lower laissez-faire leadership (r = −0.30, p < 0.01). Further, seniority correlated positively with job satisfaction (r = 0.22, p < 0.05), suggesting that more experienced coordinators report greater satisfaction; other demographics (age, gender) showed no significant relations with satisfaction or attitudes. TSE was also positively associated with TLS (r = 0.51, p < 0.01) and transactional leadership (r = 0.36, p < 0.01) but not with laissez-faire leadership (r = −0.16, ns).

Taken together, these correlations support RQ1 by showing that coordinators’ openness to remote work and their job satisfaction are meaningfully related to both experienced leadership styles and TSE.

4.1. Moderated Mediation Analysis

RQ2: Does TSE mediate the relationship between TLS and coordinators’ attitudes toward remote work?

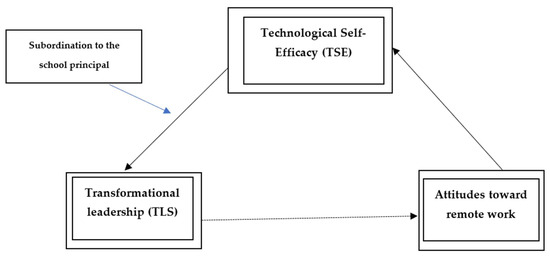

To address RQ2, we tested a moderated mediation model using SPSS’s PROCESS macro (Model 7; Hayes, 2018). The analysis examined whether TLS indirectly predicted attitudes toward remote work through TSE, with subordination to the school principal (1 = SCEC, 0 = NFEC) serving as the moderator. Age, seniority, and school proactiveness were included as covariates, and estimates were based on 5000 bootstrap samples with 95% confidence intervals.

Results indicated that TLS significantly predicted TSE among NFECs (b = 0.56, p < 0.001), but not among SCECs (b = 0.21, p = 0.07). TSE, in turn, was a strong predictor of attitudes toward remote work across the entire sample (b = 0.54, p < 0.001). For NFECs, the indirect effect of TLS on attitudes through TSE was significant (indirect effect = 0.30, 95% CI [0.17, 0.47]). The direct effect of TLS on attitudes was not significant (b = −0.01, 95% CI [−0.17, 0.17]). The index of moderated mediation was 0.19, 95% CI [0.03, 0.38], confirming that the mediation pathway operated differently depending on coordinators’ subordination to the principal.

In sum, these findings show that TSE fully mediates the relationship between TLS and attitudes toward remote work among NFECs, but not among SCECs. This moderated mediation model is visually summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

TSE mediates the relationship between TLS and attitudes, while subordination to the manager moderates the indirect relationship. Note: solid line = significant connection; dotted line = non-significant connection.

4.2. Group Comparisons

RQ3: Are there significant differences in the perceptions and experiences of SCECs compared to NFECs regarding leadership styles and technological adaptation?

To address RQ3, a one-way ANOVA with post hoc tests was conducted to compare the perceptions of job satisfaction, leadership styles, and TSE among the three participant groups: SCECs, NFECs, and Directors of Youth Departments.

The results, presented in Table 4, revealed significant differences among these groups. According to the Scheffé post hoc tests, SCECs reported significantly higher levels of work satisfaction (M = 4.24, SD = 0.83, superscript b) compared to NFECs (M = 3.37, SD = 1.47, superscript a), with directors of youth departments scoring in between (M = 3.84, SD = 0.85). This group effect was large, F(2, 176) = 10.53, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.11.

Table 4.

Comparison between SCECs, NFECs, and the directors of youth departments.

In terms of leadership styles, SCECs (M = 3.94, SD = 0.80, superscript b) and directors (M = 3.96, SD = 0.89, superscript b) reported significantly higher scores in ideal behaviors than NFECs (M = 3.55, SD = 0.90, superscript a), F(2, 176) = 3.60, p = 0.03, partial η2 = 0.04. A similar pattern was observed for motivational inspiration, where SCECs (M = 3.98, SD = 0.87) and directors (M = 3.98, SD = 0.83) scored significantly higher than NFECs (M = 3.59, SD = 0.99), F(2, 176) = 3.29, p = 0.04, partial η2 = 0.04.

By contrast, NFECs reported significantly higher laissez-faire leadership (M = 2.52, SD = 0.78, superscript b) than both SCECs (M = 2.06, SD = 0.90, superscript a) and directors (M = 1.97, SD = 0.67, superscript a), F(2, 176) = 6.50, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.07, suggesting a more hands-off leadership style among NFECs.

No significant differences were observed among the groups for TLS, ideal traits, intellectual challenge, or transactional leadership, indicating similar perceptions across these dimensions.

Taken together, these findings underscore distinct variations in leadership perceptions and job satisfaction among these educational leaders. SCECs consistently reported higher satisfaction and more favorable leadership behaviors than NFECs, while NFECs perceived their directors as more laissez-faire. These results highlight meaningful contrasts in leadership dynamics across different roles within Arab society in Israel.

5. Discussion

Before delving into the interpretation of the findings, it is crucial to reiterate that the study’s cross-sectional design allows for the examination of associations between variables but does not permit causal inferences. The insights discussed herein should be understood within this correlational framework.

5.1. Answering the Research Questions and Theoretical Integration

Our findings weave a compelling narrative about the interplay between leadership, technological confidence, and organizational context during a crisis. In line with H1, which was supported, a manager’s TLS was positively associated with both job satisfaction and positive attitudes toward remote work. This finding aligns with a broad body of literature underscoring the efficacy of TLS in enhancing motivation and adaptability, especially in times of uncertainty (Bass & Avolio, 1994; Masry-Herzallah & Stavissky, 2023). Conversely, the negative correlation found between laissez-faire leadership and job satisfaction reinforces the notion that leadership absence is detrimental to employee well-being (Yukl, 2012).

The most nuanced part of our story emerged from testing H2, which received partial, context-dependent support. Our moderated mediation analysis revealed a critical mechanism: TSE fully mediated the relationship between a leader’s TLS and coordinators’ positive attitudes, but only for NFECs. This finding powerfully illustrates a context-dependent mechanism consistent with Bandura’s (2006) self-efficacy theory. In the less-structured, resource-scarce environments of community youth departments, a transformational leader appears to function as a critical lifeline, directly building the technological confidence needed for adaptation. In contrast, for SCECs, who operate within the more robust institutional “safety net” of the formal school system, this specific pathway was not significant, suggesting other factors were at play.

Our third hypothesis (H3), which predicted lower satisfaction levels among NFECs compared to SCECs, was clearly supported. The group comparisons painted a vivid picture of two different professional realities, lending support to our alternative explanations beyond leadership alone. SCECs, who benefit from the structured support of the formal school system, reported higher job satisfaction and TSE, consistent with literature highlighting the importance of institutional resources (Masry-Herzallah & Stavissky, 2021; Masry-Herzallah et al., 2025). The challenges faced by NFECs, including political subordination to local authorities and the digital divide, likely contributed to their lower satisfaction (Weisblai, 2020; Rosner, 2020).

Finally, while not tied to a formal hypothesis, the group comparisons offered an insightful glimpse into leader-follower perception gaps. Youth department directors rated their own leadership more positively than their NFEC staff did. This perceptual gap may be explained by the lack of specific NFE leadership training for directors, a factor highlighted in previous reports (Hadad Haj-Yahya et al., 2021; Masry-Herzallah, 2023b), and underscores the importance of leadership that serves as a positive and visible role model (Bandura, 2006).

5.2. Contextualization and Practical Implications

While this study centered on the COVID-19 pandemic as a chrono-level factor impacting educational practices, it is crucial to situate the findings within the context of 2024. The pandemic triggered a widespread shift to remote work, which has since stabilized to varying extents across different sectors. Although the immediate crisis has subsided, the insights from this research remain pertinent for addressing future emergencies and continuing the integration of digital tools in education. The study’s emphasis on adaptive leadership and TSE underscores strategies that can bolster educational resilience in the face of potential disruptions, whether related to pandemics or other crises.

It is important to clarify that this study does not treat the COVID-19 period as a longitudinal context but rather as a distinct crisis phase. The findings should be interpreted within the framework of the immediate challenges presented by the pandemic, offering implications for managing similar crises in the future. The study’s exploration of the varying effects of leadership styles and TSE across different educational roles provides valuable insights for policymakers and educational leaders in crafting responsive and equitable support systems.

5.3. Ecological Systems Theory and Leadership in Arab Society

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory provided a robust framework for interpreting the complex interplay between individual, organizational, and societal factors in shaping the experiences of SCECs and NFECs during the pandemic. The study’s findings underscore the relevance of considering the broader cultural and structural contexts in leadership research, particularly in minority communities. In Israel’s Arab society, where collectivist cultural norms and hierarchical leadership structures prevail, the adoption of TLS appears to be a critical factor in enhancing job satisfaction and technological adaptation among educators.

5.4. Wide-Ranging Practical Implications

The findings underscore the need for targeted support and resources to help non-formal educators develop the technological competencies needed to effectively engage youth in online settings. The research also highlights the importance of culturally responsive leadership development initiatives that help educational leaders in Arab society navigate the tensions between traditional hierarchical leadership styles and the more collaborative, adaptive approaches demanded by the shift to remote work.

Moreover, the study emphasizes the urgent need for policymakers and organizational leaders to prioritize efforts to bridge the digital divide in Arab communities, ensuring that all youth have equitable access to the devices, internet connectivity, and digital literacy support needed to fully participate in online NFE. This may require targeted investments in infrastructure, partnerships with community organizations, and culturally relevant digital inclusion programs.

Digital literacy and culturally aware leadership will be essential for creating inclusive, equitable, and resilient learning environments in the post-pandemic period of NFE. By enhancing the technology and leadership skills of educators and addressing the digital gap in minority communities, we can ensure that all young people have the opportunity to benefit from NFE, despite the exceptional difficulties we may encounter.

5.5. Study Limitations and Future Directions

This study, while providing valuable insights into NFE, technology, and leadership in culturally diverse settings, is subject to several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design restricts the ability to draw causal inferences about the relationships between leadership styles, TSE, and attitudes toward remote work. As such, it remains unclear whether these variables influence one another over time. Future studies would benefit from employing longitudinal or experimental designs to better establish causal links and observe changes across different time periods.

Second, the reliance on self-reported data may introduce common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Despite the implementation of procedural remedies like ensuring anonymity and separating the measurement of predictor and outcome variables, social desirability or personal biases can still skew findings due to self-reports. Future research could mitigate this limitation by incorporating more objective data sources, such as third-party assessments or performance evaluations from supervisors, to validate the self-reported results.

Third, the study’s cultural setting—Arab society in Israel—presents another limitation in terms of generalizability. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory, which provides a broad framework for understanding how cultural, social, and organizational factors shape educators’ experiences, serves as the study’s foundation, but caution is necessary when applying these findings to other contexts. The specific cultural dynamics of Arab society in Israel may not fully align with those in other minority communities, and thus, future studies should investigate the applicability of these results to different cultural settings.

Fourth, while our sample size (n = 132) was adequate for the primary correlational and group comparison analyses, the moderated mediation model warrants a brief discussion. Moderated mediation analyses, particularly those with unequal subgroup sizes (85 SCECs and 47 NFECs), have greater power to detect interaction effects with larger samples. According to established guidance for such models, our sample size is sufficient for detecting medium to large effects but may be underpowered for detecting smaller interaction effects (Hayes, 2018). As such, the findings regarding the moderated mediation, while statistically significant, should be interpreted with some caution. We recommend that future research seek to replicate these results with larger and more balanced cohorts to confirm the stability of the observed effects.

6. Conclusions

In the disruptive wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, this study set out to understand how leadership and technology intersected to shape the experiences of non-formal educators in a minority community. Our central finding tells a powerful story of context: leadership is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Its impact is channeled through different mechanisms depending on the organizational ecosystem in which it operates. By applying a moderated mediation model, we moved beyond simple correlations to uncover that a leader’s ability to foster technological confidence was the critical pathway to positive adaptation for community-based educators, but not for their school-based counterparts.

Theoretically, this research advances our understanding of leadership effectiveness by demonstrating its profound context dependency. It highlights that in times of crisis, the psychological resource of technological self-efficacy can become a key mechanism through which transformational leadership translates into resilience. Practically, our findings offer a clear, actionable insight for policymakers and educational leaders: to build resilient NFE systems, particularly in underserved communities, a dual investment is necessary. First, in culturally responsive, adaptive leadership training, and second, in targeted programs designed to bolster the technological competence of educators. This is not just about providing tools; it is about building the confidence to use them.

While acknowledging the study’s limitations, including its cross-sectional design and specific cultural setting, this research provides a foundational roadmap. It underscores that in an era of ongoing disruption, sustaining equitable and effective non-formal education hinges on empowering educators with both the leadership they need and the confidence to navigate an ever-changing technological landscape.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.-H., H.S. and Z.G.; Methodology, A.M.-H., H.S. and Z.G.; Validation, A.M.-H. and Z.G.; Formal analysis, A.M.-H.; Investigation, A.M.-H. and H.S.; Data curation, A.M.-H.; Writing, review and editing, A.M.-H., H.S. and Z.G.; Visualization, A.M.-H.; Supervision, Z.G.; Project administration, A.M.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported and sponsored by The Josef Burg Chair in Education for Human Values, Tolerance and Peace, Faculty of Education, Bar Ilan University, Ramat- Gan, Israel.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study commenced following approval from Al-Qasemi College’s ethics committee in early June 2021 (Approval No.: N:062021). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committees and with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration, as revised in 2000.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all adult participants prior to participation. The Google Forms survey opened with a mandatory electronic consent item (“Do you consent to participate in this research?”). Only respondents who selected “Yes, I consent” could proceed; if “No” was selected (or the form was exited), the survey terminated and no data were recorded. No responses with a “No” selection were collected. Participation was voluntary and anonymous.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical and confidentiality restrictions but anonymized data may be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmed, M. (2023). Education in perennial crisis: Have we been asking the right questions? International Journal of Educational Development, 103, 102910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Attar, F. H., Al-Hammadi, K., & Belbase, S. (2023). Leading during COVID-19 crisis: The influence of principals’ leadership styles on teachers’ well-being in the United Arab Emirates public secondary schools. European Journal of Educational Research, 12(1), 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaydın, Ç., & Yalçın, O. M. (2024). The impact of COVID-19 on K-12 school principals’ management processes. SAGE Open, 14(3), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B. J., Walumbwa, F. O., & Weber, T. J. (2009). Leadership: Current theories, research, and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 421–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakioglu, B., Karamustafaoglu, O., Karamustafaoglu, S., & Yapici, S. (2018). The effects of out-of-school learning settings science activities on 5th graders’ academic achievement. European Journal of Educational Research, 7, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In T. Urdan, & F. Pajares (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (pp. 307–337). Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership: Good, better, best. Organizational Dynamics, 13(3), 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1994). Transformational leadership and organizational culture. International Journal of Public Administration, 17(3–4), 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1997). Full range leadership development: Manual for the multifactor leadership questionnaire. Mind Garden. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B. M., & Bass, R. (2009). The bass handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications. Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J. W. (2019). Acculturation: A personal journey across cultures. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blaak, M., Openjuru, G. L., & Zeelen, J. (2013). Non-formal vocational education in Uganda: Practical empowerment through a workable alternative. International Journal of Educational Development, 33(1), 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, A., Enosh, G., & Shor, M. (2010). Expectations of grassroots community leadership in times of normality and crisis. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 18, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burić, I., Parmač Kovačić, M., & Huić, A. (2021). Transformational leadership and instructional quality during the COVID-19 pandemic: A moderated mediation analysis. Društvena Istraživanja, 30(2), 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Population of Israel on the eve of 2022. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/mediarelease/DocLib/2021/447/11_21_447e.docx&ved=2ahUKEwj1jIfM49eQAxVe_7sIHcrsE3AQFnoECBgQAQ&usg=AOvVaw0tEdmj6HTEG5RX9f2uhftH (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Chang, T., Hong, G., Paganelli, C., Phantumvanit, P., Chang, W., Shieh, Y., & Hsu, M. (2021). Innovation of dental education during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Dental Sciences, 16(1), 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzipanagiotou, P., & Katsarou, E. (2023). Crisis management, school leadership in disruptive times and the recovery of schools in the post COVID-19 era: A systematic literature review. Education Sciences, 13(2), 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. H. (2001). A structural analysis of the R. Kahane code of informality: Elements toward a theory of informal education. Sociological Inquiry, 71(3), 357–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossan, J. (2020). Thai teachers’ self-efficacy towards educational technology integration. AU eJournal of Interdisciplinary Research, 5, 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- Da’as, R., Qadach, M., & Schechter, C. (2023). Crisis leadership: Principals’ metaphors during COVID-19. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 53(2), 357–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsen, A. H., & Petersen, M. S. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 restrictions on mental well-being and working life among Faroese employees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drory, A., & Vigoda-Gadot, E. (2010). Organizational politics and human resource management: A typology and the Israeli experience. Human Resource Management Review, 20(3), 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekvall, G. (1996). Organizational climate for creativity and innovation. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(1), 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Batri, B., Alami, A., Zaki, M., & Nafidi, Y. (2019). Extracurricular environmental activities in Moroccan middle schools: Opportunities and challenges to promoting effective environmental education. European Journal of Educational Research, 8, 1013–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Herder and Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Goldratt, M., Masry-Herzallah, A., Elfassi, Y., & Sela, Y. (2023). Capabilities of educational teams following the COVID-19 pandemic: A theoretical review for the development of a professional coherence index among social education coordinators. Ministry of Education.

- Gudek, B. (2019). Computer self-efficacy perceptions of music teacher candidates and their attitudes towards digital technology. European Journal of Educational Research, 8, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadad Haj-Yahya, N., Seif, A., Kassir, N., & Farjun, B. (2021). Education in the Arab society: Gaps and buds of change. Israel Democracy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Hallinger, P. (2014). Reviewing reviews of research in educational leadership: An empirical assessment. Educational Administration Quarterly, 50, 539–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. (2020). COVID-19—School leadership in crisis? Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 5(3/4), 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A., & Jones, M. (2020). COVID-19—School leadership in disruptive times. School Leadership & Management, 40, 243–247. [Google Scholar]

- Hayati, D., & Idin, D. (2024). Implementation of the education of the Islamic character through extracurricular activities of Pencak Silat to enhance the self-efficacy of the students. Al-Mubin: Islamic Scientific Journal, 7(1), 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst-Debby, A., Majadly, B., & Barzilai-Lumbroso, R. (2022). Journey to liberation: Israeli-Palestinian women living in Tel Aviv-Jaffa. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 45(14), 2749–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (1981). Management control of public and not-for-profit activities. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 6(3), 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, S. K., Tondeur, J., Siddiq, F., & Scherer, R. (2021). Ready, set, go! Profiling teachers’ readiness for online teaching in secondary education. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 30(1), 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussien Sayed Abdelhamid, M. (2024). Exploring purpose, practices, and impacts of non-formal education in Egypt [Master’s thesis, The American University in Cairo]. Available online: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/2282 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Jaraisy, I., & Agbaria, A. (2023). Educating for a Palestinian-Israeli identity in the young communist league of Israel (Banki): Tensions and challenges. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 18(2), 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T. A., & Piccolo, R. F. (2004). Transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(5), 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D. I., Chow, C., & Wu, A. (2003). The role of transformational leadership in enhancing organizational innovation: Hypotheses and some preliminary findings. The Leadership Quarterly, 14(4–5), 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, M., & Bakir, N. (2010). A needs assessment survey to investigate pre-service teachers’ knowledge, experiences and perceptions about preparation to using educational technologies. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology (TOJET), 9, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, C. A. (2006). Youth leadership and youth development: Connections and questions. New Directions for Youth Development, 2006(109), 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Belle, T. J. (1981). An introduction to the nonformal education of children and youth. Comparative Education Review, 25, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F. Y., Tang, H. C., Lu, S. C., Lee, Y. C., & Lin, C. C. (2020). Transformational leadership and job performance: The mediating role of work engagement. SAGE Open, 10(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, L., Hattke, F., Kalucza, J., & Redlbacher, F. (2023). Virtual work as a job demand? Work behaviors of public servants during COVID-19. Public Performance & Management Review, 46(6), 1382–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, N. (2023). Arabs in segregated vs. mixed Jewish–Arab schools in Israel: Their identities and attitudes towards Jews. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 46(12), 2720–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, R., Roberts, K. N., Terrell, R., & Lindsay, D. (2019). Cultural proficiency: A manual for school leaders (4th ed.). Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, P. D., Gregersen, T., & Mercer, S. (2020). Language teachers’ coping strategies during the COVID-19 conversion to online teaching: Correlations with stress, wellbeing and negative emotions. System, 94, 102352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel-Levy, N., & Artzi, A. (Eds.). (2016). Informal education for children, youth and young adults in Israel: Testimonials from the field and a summary of the learning process. The Initiative for Applied Research in Education, Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, J., Chiu, C. Y., Owens, B. P., Brown, J. A., & Liao, J. (2019). Growing followers: Exploring the effects of leader humility on follower self-expansion, self-efficacy, and performance. Journal of Management Studies, 56(2), 343–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masry-Herzallah, A. (2023a). Factors promoting and inhibiting teachers’ perception of success in online teaching during the COVID-19 crisis. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 28(4), 1635–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masry-Herzallah, A. (2023b). The relationship between transformational leadership and affective commitment: A study of Arab non-formal education coordinators in Israel. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 19(4), 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masry-Herzallah, A., & Cohen, A. (2024). Agents of change or collaborators? The first Palestinian students from Eastern Jerusalem studying to become Hebrew teachers in an Israeli university. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 32(5), 1455–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masry-Herzallah, A., & Dor-Haim, P. (2024). Jewish and Arab teachers’ views on school communications, innovation and commitment after COVID-19: Sector of education as a moderator. International Journal of Educational Management, 38(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masry-Herzallah, A., Sarhan, H., & Gross, Z. (2025). Transformational leadership and technological competence in non-formal education: Implications for equitable access and digital inclusion. International Journal of Instruction, 18(2), 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masry-Herzallah, A., & Stavissky, Y. (2021). The attitudes of elementary and middle school students and teachers towards online learning during the corona pandemic outbreak. SN Social Sciences, 1(3), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masry-Herzallah, A., & Stavissky, Y. (2023). The relationship between frequency of online teaching and TPACK improvement during COVID-19: The moderating role of transformational leadership and sector. International Journal of Educational Management, 37(5), 929–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mell, I., & Somech, A. (2023). Citizenship Pressure in non-formal education organizations: Leaders’ idealized influence and organizational identification. European Journal of Educational Management, 6, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, M. D., Scott, G. M., Gaddis, B., & Strange, J. M. (2002). Leading creative people: Orchestrating expertise and relationships. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(6), 705–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netithanakul, A. (2017). The impact of transformational leadership on learning organization: A case study of Saraburi provincial non-formal and informal education centre. RSU International Journal of College of Government (RSUIJCG), 4, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Nissilä, S.-P., Karjalainen, A., & Koukkari, M. (2022). It is the shared aims, trust and compassion that allow people to prosper: Teacher educators’ lifelong learning in competence-based education. European Journal of Educational Research, 11, 965–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novrita, J., Elizarni, Oktavia, R., & Sari, T. Y. (2025). Making ‘Taman Baca’ Sustainable”, lessons learned from community-based non-formal education in Aceh, Indonesia. International Journal of Educational Development, 113, 103186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M. N., & Ismail, S. N. (2020). Mobile technology integration in the 2020s: The impact of technology leadership in the Malaysian context. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(5), 1874–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyedotun, T. D. (2020). Sudden change of pedagogy in education driven by COVID-19: Perspectives and evaluation from a developing country. Research in Globalization, 2, 100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltola, J. P., Lindfors, E., & Luukka, E. (2024). Exploring crisis management measures taken by school leaders at the unpredictable crisis—Case COVID-19. Journal of Educational Change, 25(4), 727–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A. (2019). Second-generation non-formal education and the sustainable development goals: Operationalising the SDGs through community learning centres. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 38(5), 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romi, S., & Schmida, M. (2009). Non-formal education: A major educational force in the postmodern era. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39(2), 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, D. (2020). Informal education in Israel during the coronavirus crisis: Mapping and reviewing activities in real time. Mandel Leadership Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Savitri, E., & Sudarsyah, A. (2021, October 21). Transformational leadership for improving teacher’s performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. 4th International Conference on Research of Educational Administration and Management (ICREAM 2020) (pp. 308–312), Bandung, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Serhan, H. (2023). The contribution of participation in informal education in childhood and youth in Arab society in Israel to fostering a sense of self-efficacy, belonging, and community engagement in adulthood [Master’s thesis, Bar-Ilan University]. [Google Scholar]

- Shafaei, A., Farr-Wharton, B., Omari, M., Pooley, J. A., Bentley, T., Sharafizad, F., & Onnis, L. (2023). Leading through tumultuous events in public sector organizations. Public Performance & Management Review, 46(6), 1287–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffer, O. (2023). To lead at 17: Teenage girls leadership in the scouts. Journal of Adolescent Research, 40(4), 1049–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simac, J., Marcus, R., & Harper, C. (2021). Does non-formal education have lasting effects? Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 51(5), 706–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sion, L. (2014). Passing as hybrid: Arab-Palestinian teachers in Jewish schools. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 37(14), 2636–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soles, B., Flores, P., III, Domingues, J., & Solis, F. (2020). The role of formal and nonformal leaders in creating culturally proficient educational practices. In P. Keough (Ed.), Overcoming current challenges in the P-12 teaching profession (pp. 144–172). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannous, N. (2022). Social education—The Arab middle school in Israel. In A. Shayesh, & D. Yuval (Eds.), Non-formal education as a social and values-generalized pedagogy (pp. 211–224). Tel Aviv University. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Van der Linden, J. (2015). Non-formal education and new partnerships in a (post-)conflict situation: ‘Three cooking stones supporting one saucepan’. International Journal of Educational Development, 42, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, D. A., Ramirez, G. G., House, R. J., & Puranam, P. (2001). Does leadership matter? CEO leadership attributes and profitability under conditions of perceived environmental uncertainty. The Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisblai, A. (2020). Non-formal education activities in the shadow of the coronavirus. Knesset Research and Information Center. (In Hebrew)

- Widodo, W., Mundzir, S., Fatchan, A., & Hardika, H. (2017, September 22). Analysis of non-formal education leadership. 3rd NFE Conference on Lifelong Learning (NFE 2016) (pp. 230–235), Bandung, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G. (2012). Effective leadership behavior: What we know and what questions need more attention. Academy of Management Perspectives, 26(4), 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).