Ready or Not? Greek K-12 Teachers’ Psychological Readiness for Bringing the EU into the Classroom

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Teachers’ Reality in Greece vs. EU Awareness

1.2. Teachers’ Burnout and Individual Differences

1.3. Personality and Teachers’ Burnout

1.4. Self-Determination Theory

1.5. Well-Being and Mental Health

1.6. Aim of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographic Information

2.3.2. European Engagement and Teaching Readiness Scale (EETRS-62)—Bringing the EU into the Classroom

2.3.3. IPIP Big-Five Personality Questionnaire

2.3.4. Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale (BPNSNF)

2.3.5. Flourishing Scale (FS)

2.3.6. Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale

2.3.7. Depression—Anxiety—Stress (Dass-21)

2.3.8. Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI-ED Version for Teachers)

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and the Latent Structure of the Scale

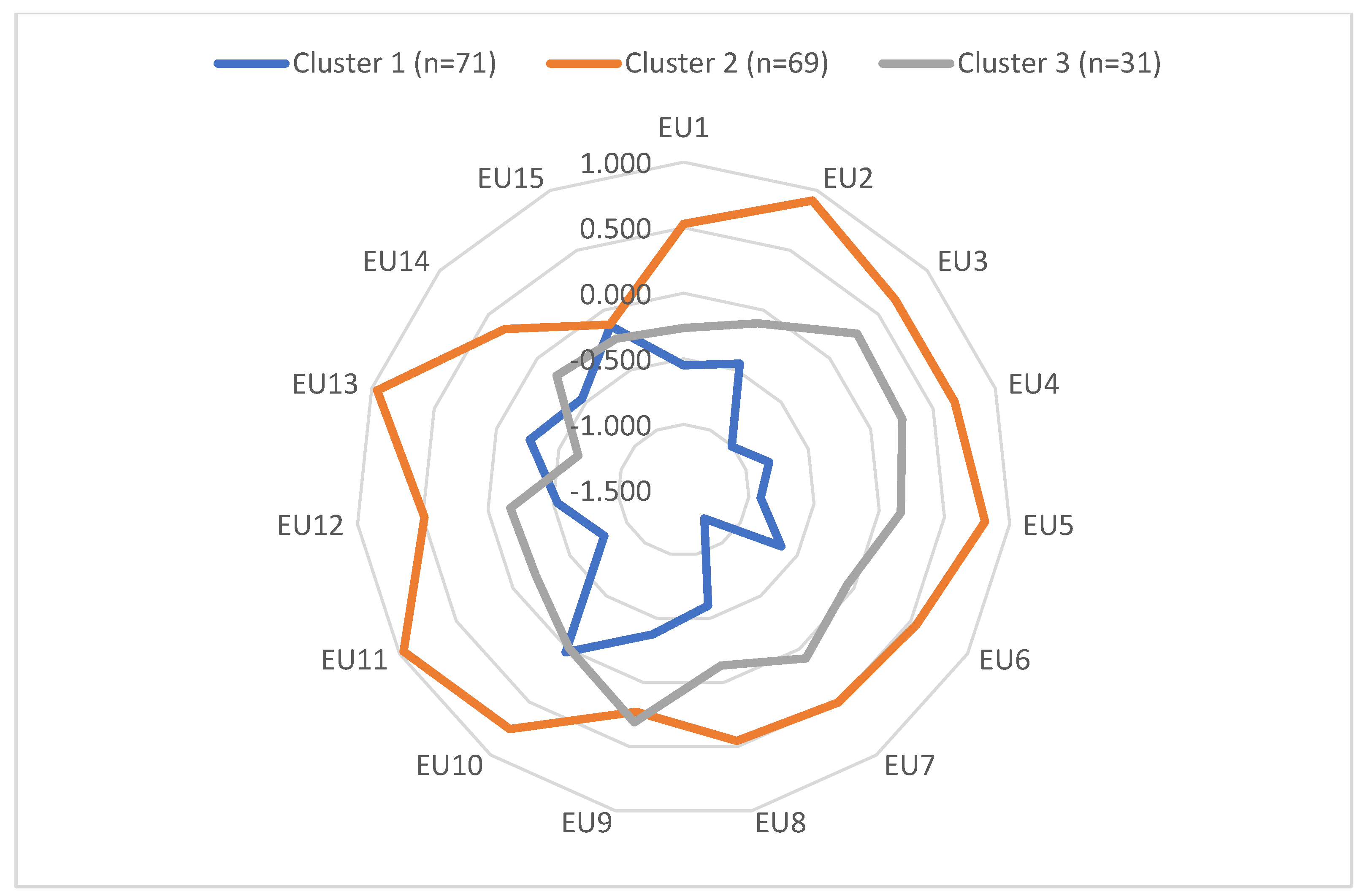

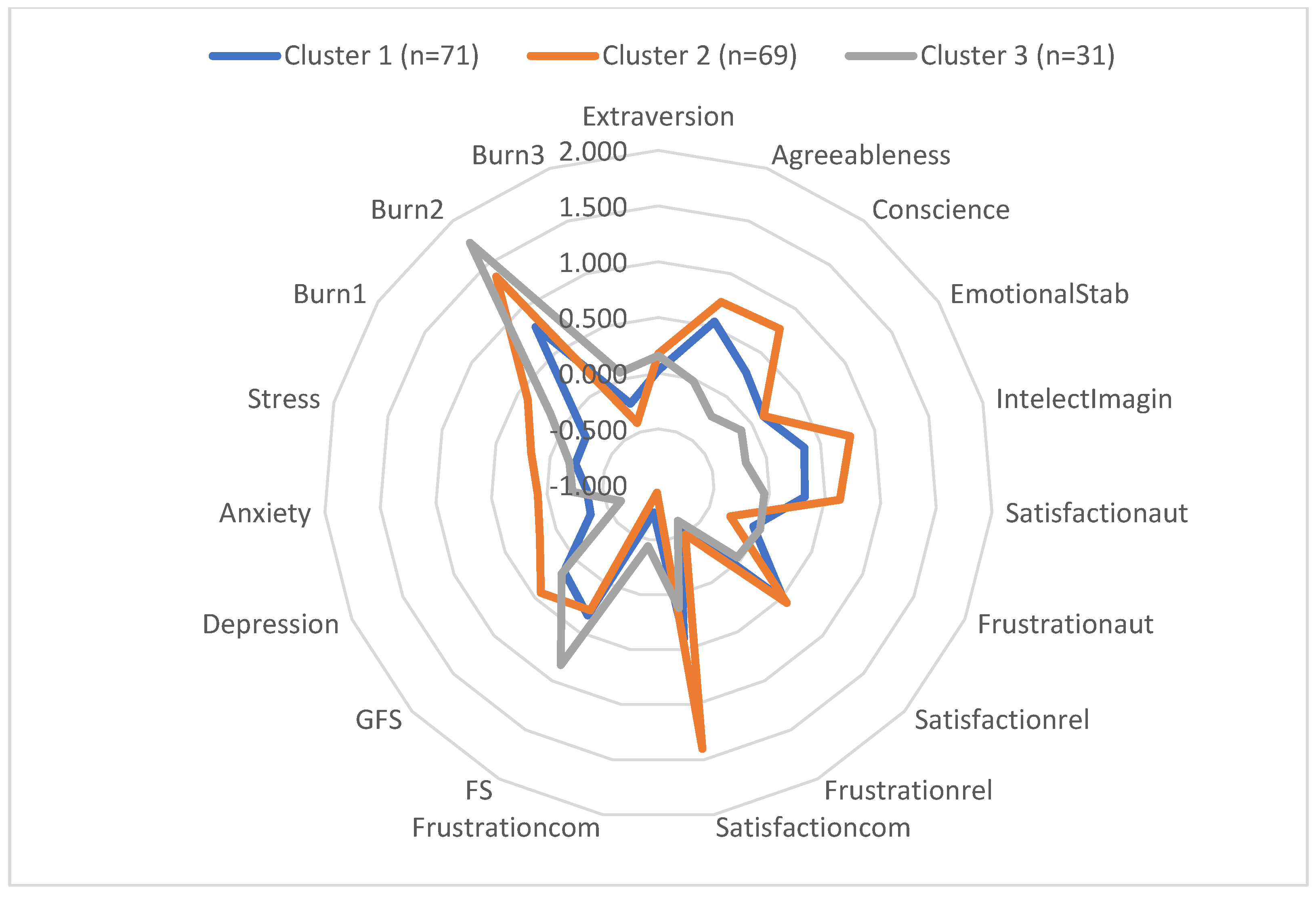

Cluster Analysis (EETRS-Based Engagement Profiles)

3.2. Multinomial Regression

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EEA | European Education Area |

| EU | European Union |

| BPNSNF | Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale |

| FS | Flourishing Scale |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| GSE | Generalized Self-efficacy |

| K-12 Teachers | Teachers working from kindergarten through 12th grade |

| SDT | Self-determination theory |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Appendix A

| Big Five | BPNSNF | FS | GFS | Dass | Burnout | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFI | 0.930 | 0.991 | 0.991 | 0.993 | 0.990 | 0.967 |

| NFI | 0.880 | 0.978 | 0.988 | 0.990 | 0.974 | 0.954 |

| TLI | 0.926 | 0.990 | 0.988 | 0.991 | 0.989 | 0.963 |

| GFI | 0.920 | 0.983 | 0.992 | 0.991 | 0.982 | 0.967 |

| AGFI | 0.903 | 0.974 | 0.972 | 0.981 | 0.972 | 0.947 |

| RMSEA | 0.086 | 0.064 | 0.119 | 0.114 | 0.060 | 0.123 |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.021 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.104 | 0.000 |

| SRMR | 0.116 | 0.071 | 0.064 | 0.072 | 0.080 | 0.108 |

| Scale | Subscale | Alpha | Alpha (Ord.) | Omega1 | Omega2 | Omega3 | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Big Five | Extraversion | 0.814 | 0.860 | 0.828 | 0.828 | 0.775 | 0.470 * |

| Agreeableness | 0.827 | 0.894 | 0.849 | 0.849 | 0.882 | 0.491 | |

| Conscience | 0.766 | 0.862 | 0.768 | 0.768 | 0.712 | 0.398 | |

| EmotionalStab | 0.821 | 0.852 | 0.846 | 0.846 | 0.885 | 0.419 | |

| IntelectImagin | 0.776 | 0.853 | 0.820 | 0.820 | 0.865 | 0.434 * | |

| BPNSNF | Satisfactionaut | 0.822 | 0.867 | 0.818 | 0.818 | 0.815 | 0.627 * |

| Frustrationaut | 0.669 | 0.698 | 0.637 | 0.637 | 0.595 | 0.380 | |

| Satisfactionrel | 0.810 | 0.865 | 0.817 | 0.817 | 0.825 | 0.636 * | |

| Frustrationrel | 0.739 | 0.828 | 0.785 | 0.785 | 0.816 | 0.579 | |

| Satisfactioncom | 0.848 | 0.917 | 0.857 | 0.857 | 0.863 | 0.746 | |

| Frustrationcom | 0.763 | 0.854 | 0.785 | 0.785 | 0.778 | 0.596 | |

| FS | FS | 0.887 | 0.923 | 0.895 | 0.895 | 0.908 | 0.614 |

| GFS | GFS | 0.902 | 0.941 | 0.907 | 0.907 | 0.923 | 0.653 |

| Dass | Depression | 0.850 | 0.915 | 0.856 | 0.856 | 0.870 | 0.628 * |

| Anxiety | 0.817 | 0.877 | 0.805 | 0.805 | 0.817 | 0.524 * | |

| Stress | 0.780 | 0.857 | 0.780 | 0.780 | 0.774 | 0.478 * | |

| Burnout | Burn1 (Emotional Burnout) | 0.849 | 0.877 | 0.854 | 0.854 | 0.759 | 0.535 |

| Burn2 (Depersonalization) | 0.574 | 0.724 | 0.621 | 0.621 | 0.608 | 0.393 * | |

| Burn3 (Accomplishment) | 0.874 | 0.911 | 0.890 | 0.890 | 0.910 | 0.585 |

References

- Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., Haerens, L., Soenens, B., Fontaine, J. R. J., & Reeve, J. (2016). Changing teachers’ beliefs regarding autonomy support and structure: The role of experienced psychological need satisfaction in teacher training. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 23, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, B., Obuobi-Donkor, G., Burback, L., & Wei, Y. (2022). Stress, burnout, anxiety and depression among teachers: A scoping review. International Journal of Eenvironmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiadou, N. (2007). The Europeanisation of education policy: Researching changing governance and “new” modes of coordination. Research in Comparative and International Education, 2(2), 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloe, A. M., Shisler, S. M., Norris, B. D., Nickerson, A. B., & Rinker, T. W. (2014). A multivariate meta-analysis of student misbehavior and teacher burnout. Educational Research Review, 12, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asderaki, F. (2022). The European Education Area(s): Towards a new governance architecture in education and training. In D. Anagnostopoulou, & D. Skiadas (Eds.), Higher education and research in the European union: Mobility schemes, social rights and youth policies (pp. 125–147). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asderaki, F., & Sideri, O. (2020). Teaching EU values in schools through European programs during COVID-19 pandemic. The “Teachers4Europe: Setting an Agora for democratic culture” program. HAPSc Policy Briefs Series, 1(1), 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asderaki, F., Tzagkarakis, S. I., & Kritas, D. (2023). Curricula mapping, qualitative and quantitative outcomes report: “Motivating Teachers for Europe” 2022–2025. University of Piraeus Research Center. ISBN 978-960-6897-19-1. [Google Scholar]

- Avola, P., Soini-Ikonen, T., Jyrkiäinen, A., & Pentikäinen, V. (2025). Interventions to teacher well-being and burnout A scoping review. Educational Psychology Review, 37(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellibaş, M. Ş., Gümüş, S., & Chen, J. (2024). The impact of distributed leadership on teacher commitment: The mediation role of teacher workload stress and teacher well-being. British Educational Research Journal, 50(2), 814–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G. (2009). What kind of citizenship for European higher education? Beyond the competent active citizen. European Educational Research Journal, 8(2), 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A., Scantlebury, A., Hughes-Morley, A., Mitchell, N., Wright, K., Scott, W., & McDaid, C. (2017). Mental health training programmes for non-mental health trained professionals coming into contact with people with mental ill health: A systematic review of effectiveness. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, J., Coldwell, M., Müller, L. M., Perry, E., & Zuccollo, J. (2021). Mid-career teachers: A mixed methods scoping study of professional development, career progression and retention. Education Sciences, 11(6), 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullough, R. V., & Pinnegar, S. (2009). The happiness of teaching (as eudaimonia): Disciplinary knowledge and the threat of performativity. Teachers and Teaching, 15(2), 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burić, I., Slišković, A., & Penezić, Z. (2019). Understanding teacher well-being: A cross-lagged analysis of burnout, negative student-related emotions, psychopathological symptoms, and resilience. Educational Psychology, 39(9), 1136–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calandri, E., Mastrokoukou, S., Marchisio, C., Monchietto, A., & Graziano, F. (2025). Teacher emotional competence for inclusive education: A systematic review. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, M., & Lovett, S. (2015). Sustaining the commitment and realising the potential of highly promising teachers. Teachers and Teaching, 21(2), 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canrinus, E. T., Helms-Lorenz, M., Beijaard, D., Buitink, J., & Hofman, A. (2011). Profiling teachers’ sense of professional identity. Educational Studies, 37(5), 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charrad, M., Ghazzali, N., Boiteau, V., & Niknafs, A. (2014). NbClust: An R package for determining the relevant number of clusters in a data set. Journal of Statistical Software, 61(6), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B., Van Assche, J., Vansteenkiste, M., Soenens, B., & Beyers, W. (2015a). Does psychological need satisfaction matter when environmental or financial safety are at risk? Journal of Happiness Studies, 16, 745–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., Duriez, B., Lens, W., Matos, L., Mouratidis, A., Ryan, R. M., Sheldon, K. M., Soenens, B., Van Petegem, S., & Verstuyf, J. (2015b). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., & Perry, N. E. (2012). School climate and social-emotional learning: Predicting teacher stress, job satisfaction, and teaching efficacy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104, 1189–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1988). Personality in adulthood: A six-year longitudinal study of self-reports and spouse ratings on the NEO Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(5), 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and” why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q., Zheng, B., & Chen, J. (2020). The relationship between personality traits, resilience, school support, and creative teaching in higher school physical education teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 568906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrumaux, P., Lapointe, D., Ntsame Sima, M., Boudrias, J.-S., Savoie, A., & Brunet, L. (2015). The impact of job demands, climate, and optimism on well-being and distress at work: What are the mediating effects of basic psychological need satisfaction? European Review of Applied Psychology, 65, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1986, September). Experience and education. In The educational forum (Vol. 50, No. 3, pp. 241–252). Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2009). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebersold, S., Rahm, T., & Heise, E. (2019). Autonomy support and well-being in teachers: Differential mediations through basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration. Social Psychology of Education, 22, 921–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2022). Education and training monitor 2022: Country analysis—Greece (SWD(2022) 751 final). Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/cd653a8f-66f4-11ed-b14f-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Eurostat. (2025). Female teachers—As % of all teachers, by education level. Eurostat. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carmona, M., Marín, M. D., & Aguayo, R. (2019). Burnout syndrome in secondary school teachers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Psychology of Education, 22, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkamari, M., & Fotopoulou, V. (2024). Burnout syndrome dimensions as perceived by kindergarten teachers and elementary school teachers in Greece. European Journal of Education and Pedagogy, 5(5), 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L. R. (1992). The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychological Assessment, 4, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L. R., Johnson, J. A., Eber, H. W., Hogan, R., Ashton, M. C., Cloninger, C. R., & Gough, H. G. (2006). The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(1), 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C., Wilcox, G., & Nordstokke, D. (2017). Teacher mental health, school climate, inclusive education and student learning: A review. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 58(3), 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, F., Mastrokoukou, S., Monchietto, A., Marchisio, C., & Calandri, E. (2024). The moderating role of emotional self-efficacy and gender in teacher empathy and inclusive education. Scientific Reports, 14, 22587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T., & Waber, J. (2021). Teacher well-being: A systematic review of the research literature from the year 2000–2019. Educational Research Review, 34, 100411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W., & Zhao, H. (2019). A study on the influence of five personalities of vocational college teachers on job burnout in Northwest. Qinghai Journal of Ethnology, 20(4), 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidou, A. (2007). A comparative analysis of new governance instruments in the transnational educational space: A shift to knowledge-based instruments? European Educational Research Journal, 6(4), 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalamara, E., & Richardson, C. (2022). Using latent profile analysis to understand burnout in a sample of Greek teachers. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 95(1), 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R. M., Perry, N. E., & Frenzel, A. C. (2011). Teachers’ relatedness with students: An underemphasized component of teachers’ basic psychological needs. Journal of School Psychology, 104, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (3rd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. FT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Komarraju, M., Karau, S. J., Schmeck, R. R., & Avdic, A. (2011). The Big Five personality traits, learning styles, and academic achievement. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(4), 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y. (2021). The role of experiential learning on students’ motivation and classroom engagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 771272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law 3848/2010. (2010). Upgrade of the role of the teacher—Establishment of evaluation and meritocracy rules in education and other provisions [Official Gazette A’ 71/19.05.2010]. National Printing Office. Available online: https://www.et.gr (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Law 4823/2021. (2021). Upgrading school quality, empowerment of teachers and other provisions [Official Gazette A’ 136/03.08.2021]. National Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L., & Ruppar, A. (2021). Conceptualizing teacher agency for inclusive education: A systematic and international review. Teacher Education and Special Education, 44(1), 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. (2023). The effect of teacher self-efficacy, teacher resilience, and emotion regulation on teacher burnout: A mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1185079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Li, Y., Zhu, W., He, Y., & Li, D. (2022). A meta-analysis of teachers’ job burnout and Big Five personality traits. Frontiers in Education, 7, 822659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, L., Rodeyns, J., Thomas, V., Mednick, F. J., De Backer, F., & Lombaerts, K. (2023). Primary school teachers’ perceptions of critical thinking promotion in European schools system. Education 3–13, 51(8), 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F., Youssef, C. M., & Avolio, B. J. (2006). Psychological capital: Developing the human competitive edge. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, M. R. (1986). Determination and quantification of content validity. Nursing Research, 35(6), 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, P. C., Tinoca, L., & Alves, M. G. (2024). On the effects of Erasmus+ KA 1 mobilities for continuing professional development in teachers’ biographies: A qualitative research approach with teachers in Portugal. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 7, 100368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. (1986). Maslach burnout inventory manual. Consulting Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Maslach burnout inventory manual (3rd ed.). Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (2003). Personality in adulthood: A five-factor theory perspective (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meher, V., Sahu, T., Meher, S., & Bariha, K. (2025). The influence of emotional maturity and psychological Well-being on teachers’ professional development in Integrated Teacher education Programmes: A Systematic review. Asian Journal of Education and Social Studies, 51(1), 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milienos, F. S., Rentzios, C., Catrysse, L., Gijbels, D., Mastrokoukou, S., Longobardi, C., & Karagiannopoulou, E. (2021). The contribution of learning and mental health variables in first-year students’ profiles. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miquel, E., Monguillot, M., Soler, M., & Duran, D. (2024). Reciprocal peer observation: A mechanism to identify professional learning goals. Education Inquiry, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norwich, B., Moore, D., Stentiford, L., & Hall, D. (2022). A critical consideration of ‘mental health and wellbeing’in education: Thinking about school aims in terms of wellbeing. British Educational Research Journal, 48(4), 803–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nousia, A., & Karagiannopoulou, E. (2017). Associations between late elementary school students’ perceptions of teachers’ burnout and perceptions of the classroom climate. American Journal of Educational Research, 4(1), 13–23. Available online: https://escijournals.net/index.php/IJES/article/download/2203/1039 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- OECD. (2024). Education at a glance 2024: OECD indicators—Greece country note. OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/09/education-at-a-glance-2024-country-notes_532eb29d/greece_83703687/423881a4-en.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Özdemir, N., Çoban, Ö., Buyukgoze, H., Gümüş, S., & Pietsch, M. (2024). Leading knowledge exploration and exploitation in schools: The moderating role of teachers’ open innovation mindset. Educational Administration Quarterly, 60(5), 668–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadeli, C., Filippou, A., Nikolakaki, M., Papadelis, I., & Korsavvidis, D. (2022). Economic Crisis and Educational Reforms: How Burnout affects Teachers’ Physical, Mental, and Oral Health? Asian Journal of Humanities and Social Studies, 10(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2006). The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health, 29(5), 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protothema. (2023, September 5). Έγκριση πρόσληψης 41.900 αναπληρωτών εκπαιδευτικών για το τρέχον έτος από το υπουργείο Παιδείας [Approval of 41,900 substitute teacher hires for the current year by the Ministry of Education]. Available online: https://www.protothema.gr/greece/article/1551011/egrisi-proslipsis-41900-anapliroton-ekpaideutikon-gia-to-trehon-etos-apo-to-upourgeio-paideias/ (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2020). Teacher burnout profiles and proactive strategies. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 35, 701–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raykov, T., & Marcoulides, G. A. (2006). A first course in structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2008). Self-determination theory and the role of basic psychological needs in personality and the organization of behavior. In L. A. Pervin, R. W. Robins, & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 654–678). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Savvides, N. (2006). Comparing the promotion of European identity at three ‘European Schools’: An analysis of teachers’ perceptions. Research in Comparative and International Education, 1(4), 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schratz, M. (2014). The European teacher: Transnational perspectives in teacher education policy and practice. Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal, 4(4), 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (pp. 35–37). NFER-NELSON. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, S., & Castellan, N. J. (1988). Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2014). Teacher self-efficacy and perceived autonomy: Relations with teacher engagement, job satisfaction, and emotional exhaustion. Psychological Reports, 114(1), 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeonidis, V. (2018). Revisiting the European teacher education area: The transformation of teacher education policies and practices in Europe. CEPS Journal, 8(3), 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traianou, A. (2023). The intricacies of conditionality: Education policy review in Greece 2015–2018. Journal of Education Policy, 38(2), 342–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsekou, A., Papadopoulou, A., & Xanthippi, F. (2023). Evaluation of Teaching Mobilities in the Context of Intercultural Education. Journal of General Education and Humanities, 2(2), 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M., Ryan, R. M., & Soenens, B. (2020). Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motivation and Emotion, 44(1), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachopanou, P., & Karagiannopoulou, E. (2021). Defense styles, academic procrastination, psychological wellbeing, and approaches to learning. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 210(3), 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlachopanou, P., Karagiannopoulou, E., & Ntritsos, G. (2023). The relationship between defenses and learning: The mediating role of procrastination and well-being among undergraduate students. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 211(1), 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2019). World health statistics overview 2019. WHO. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311696/WHO-DAD-2019.1-eng.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Zumbo, B. D., Gadermann, A. M., & Zeisser, C. (2007). Ordinal versions of coefficients alpha and theta for Likert rating scales. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods, 6, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Third-Order | Second-Order | |

|---|---|---|

| CFI | 0.957 | 0.967 |

| NFI | 0.942 | 0.952 |

| TLI | 0.955 | 0.965 |

| GFI | 0.949 | 0.958 |

| AGFI | 0.939 | 0.950 |

| RMSEA | 0.127 (p < 0.001) | 0.111 (p < 0.001) |

| SRMR | 0.115 | 0.106 |

| Chi-square | 6765.9 (df = 1810) | 5543.1 (df = 1796) * |

| EUs1 | EUs2 | EUs3 | EUs4 | EUs5 * | EUs6 | EUs7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFI | 0.965 | 0.987 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.997 | 0.997 | 0.994 |

| NFI | 0.942 | 0.982 | 0.997 | 0.999 | 0.995 | 0.997 | 0.992 |

| TLI | 0.958 | 0.982 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.996 | 0.992 | 0.992 |

| GFI | 0.968 | 0.986 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.997 | 0.998 | 0.994 |

| AGFI | 0.944 | 0.967 | 0.995 | 0.997 | 0.981 | 0.973 | 0.979 |

| RMSEA | 0.090 | 0.128 | 0.000 | 0.059 | 0.072 | 0.146 | 0.121 |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.997 | 0.303 | 0.273 | 0.035 | <0.001 |

| SRMR | 0.090 | 0.073 | 0.038 | 0.035 | 0.033 | 0.051 | 0.050 |

| Scale | Subscale | Alpha | Alpha (Ord.) | Omega1 | Omega2 | Omega3 | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUs1 | EU1 (6) | 0.787 | 0.831 | 0.806 | 0.806 | 0.807 | 0.485 |

| EU2 (2) | 0.420 | 0.481 | 0.473 | 0.473 | 0.473 | 0.372 * | |

| EU3 (4) | 0.787 | 0.852 | 0.814 | 0.814 | 0.841 | 0.623 | |

| EU4 (5) | 0.728 | 0.763 | 0.752 | 0.752 | 0.756 | 0.429 * | |

| EUs2 | EU5 (5) | 0.826 | 0.855 | 0.844 | 0.844 | 0.864 | 0.573 |

| EU6 (2) | 0.697 | 0.752 | 0.695 | 0.695 | 0.695 | 0.627 | |

| EU7 (4) | 0.875 | 0.916 | 0.897 | 0.897 | 0.929 | 0.772 | |

| EUs3 | EU8 (4) | 0.859 | 0.889 | 0.862 | 0.862 | 0.865 | 0.672 |

| EU9 (3) | 0.894 | 0.950 | 0.894 | 0.894 | 0.892 | 0.863 | |

| EU10 (3) | 0.895 | 0.949 | 0.896 | 0.896 | 0.898 | 0.864 | |

| EUs4 | EU11 (4) | 0.954 | 0.973 | 0.954 | 0.954 | 0.958 | 0.905 |

| EU12 (5) | 0.922 | 0.943 | 0.919 | 0.919 | 0.932 | 0.782 | |

| EUs5 | EU13 (3) | 0.777 | 0.847 | 0.792 | 0.792 | 0.795 | 0.656 |

| EUs6 | EU14 (4) | 0.830 | 0.863 | 0.843 | 0.843 | 0.853 | 0.645 |

| EUs7 | EU15 (8) | 0.910 | 0.925 | 0.907 | 0.907 | 0.915 | 0.619 |

| Cluster 1 (n = 71) | Cluster 2 (n = 69) | Cluster 3 (n = 31) | Cluster 1 vs. 2 | Cluster 1 vs. 3 | Cluster 2 vs. 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU1 | −0.550 | 0.528 | −0.265 | TRUE | TRUE | |

| EU2 | −0.446 | 0.916 | −0.109 | TRUE | TRUE | |

| EU3 | −1.005 | 0.671 | 0.281 | TRUE | TRUE | |

| EU4 | −0.815 | 0.674 | 0.253 | TRUE | TRUE | |

| EU5 | −0.908 | 0.810 | 0.166 | TRUE | TRUE | TRUE |

| EU6 | −0.639 | 0.551 | −0.058 | TRUE | TRUE | |

| EU7 | −1.231 | 0.504 | 0.087 | TRUE | TRUE | TRUE |

| EU8 | −0.598 | 0.455 | −0.131 | TRUE | TRUE | |

| EU9 | −0.375 | 0.230 | 0.312 | TRUE | TRUE | |

| EU10 | 0.029 | 0.754 | −0.012 | TRUE | TRUE | |

| EU11 | −0.801 | 0.964 | −0.199 | TRUE | TRUE | |

| EU12 | −0.535 | 0.487 | −0.172 | TRUE | TRUE | |

| EU13 | −0.266 | 0.957 | −0.656 | TRUE | TRUE | |

| EU14 | −0.460 | 0.333 | −0.198 | TRUE | TRUE | |

| EU15 | −0.130 | −0.120 | −0.237 | TRUE | TRUE |

| Scale | Subscale | Cluster 1 (n = 71) | Cluster 2 (n = 69) | Cluster 3 (n = 31) | Cluster 1 vs. 2 | Cluster 1 vs. 3 | Cluster 2 vs. 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Big Five | Extraversion * | 0.027 | 0.175 | 0.157 | |||

| Agreeableness * | 0.548 | 0.733 | −0.021 | TRUE | |||

| Conscience * | 0.278 | 0.771 | −0.224 | TRUE | |||

| EmotionalStab | 0.124 | 0.127 | −0.111 | ||||

| IntelectImagin * | 0.350 | 0.774 | −0.191 | TRUE | TRUE | ||

| BPNSNF ** | Satisfactionaut * | 0.316 | 0.634 | −0.046 | TRUE | ||

| Frustrationaut | −0.071 | −0.296 | −0.004 | ||||

| Satisfactionrel | 0.530 | 0.565 | −0.037 | ||||

| Frustrationrel | −0.593 | −0.493 | −0.633 | ||||

| Satisfactioncom * | 0.396 | 1.400 | 0.120 | TRUE | TRUE | ||

| Frustrationcom | −0.748 | −0.927 | −0.441 | ||||

| FS ** | FS | 0.332 | 0.280 | 0.838 | |||

| GFS ** | GFS * | 0.148 | 0.431 | 0.179 | TRUE | ||

| Dass | Depression | −0.338 | 0.160 | −0.635 | |||

| Anxiety | −0.357 | 0.084 | −0.228 | ||||

| Stress | −0.233 | 0.175 | −0.177 | ||||

| Burnout | Burn1 (Emotional Burnout) * | −0.223 | 0.399 | 0.152 | TRUE | TRUE | |

| Burn2 (Depersonalization) | 0.793 | 1.366 | 1.749 | ||||

| Burn3 (Accomplishment) * | −0.232 | −0.413 | 0.063 | TRUE |

| Cluster 1 (n = 71) | Cluster 2 (n = 69) | Cluster 3 (n = 31) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude (overall) towards the EU * | 1 (very pessimistic) | 7.2% | 2.9% | 0% |

| 2 | 27.5% | 7.2% | 12.9% | |

| 3 | 43.5% | 26.1% | 61.3% | |

| 4 | 20.3% | 42.0% | 25.8% | |

| 5 (very optimistic) | 1.4% | 21.7% | 0% | |

| Gender | Male | 15.5% | 20.3% | 32.3% |

| Female | 84.5% | 79.7% | 67.7% | |

| Experience | <1 year | 0% | 1.4% | 0% |

| 1–5 years | 11.3% | 5.8% | 16.1% | |

| 6–10 years | 2.8% | 4.3% | 6.5% | |

| 11–15 years | 15.5% | 5.8% | 9.7% | |

| 16–20 years | 18.3% | 23.2% | 35.5% | |

| >20 years | 52.1% | 59.4% | 32.3% | |

| Education * | Graduate | 22.5% | 10.1% | 12.9% |

| MSc | 69.0% | 59.4% | 64.5% | |

| Phd | 8.5% | 30.4% | 22.6% | |

| Sector (work) | Other | 1.4% | 2.9% | 6.5% |

| Public | 93.0% | 88.4% | 83.9% | |

| Private | 5.6% | 8.7% | 9.7% | |

| School (work) * | Other | 1.4% | 6.5% | |

| Primary | 62.0% | 44.9% | 74.2% | |

| Secondary | 28.2% | 53.6% | 9.7% | |

| Vocational High School | 8.5% | 1.4% | 9.7% | |

| Age ** | 47.099 | 49.319 | 45.290 |

| Coef. 2 | Coef. 3 | Std. Errors 2 | Std. Errors 3 | Odds 2 | Odds 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.168 | 2.001 | 1.411 | 1.777 | 0.846 | 7.395 |

| Extraversion | 0.037 | 0.590 * | 0.296 | 0.365 | 1.038 | 1.804 |

| Agreeableness | 0.026 | −0.712 * | 0.179 | 0.415 | 1.026 | 0.491 |

| Conscience | 0.028 | −0.593 | 0.121 | 0.422 | 1.028 | 0.553 |

| EmotionalStab | −0.139 | −0.399 | 0.230 | 0.406 | 0.870 | 0.671 |

| IntelectImagin | −0.004 | −0.176 | 0.091 | 0.379 | 0.996 | 0.839 |

| Satisfactionaut | −0.023 | −0.184 | 0.197 | 0.428 | 0.978 | 0.832 |

| Frustrationaut | 0.027 | −0.030 | 0.182 | 0.351 | 1.028 | 0.970 |

| Satisfactionrel | −0.005 | −0.456 | 0.183 | 0.379 | 0.995 | 0.634 |

| Frustrationrel | 0.235 | −0.084 | 0.171 | 0.216 | 1.265 | 0.919 |

| Satisfactioncom | 0.514 *** | −0.099 | 0.188 | 0.287 | 1.672 | 0.906 |

| Frustrationcom | 0.183 | −0.028 | 0.142 | 0.185 | 1.201 | 0.973 |

| FS | −0.018 | 0.376 ** | 0.132 | 0.179 | 0.982 | 1.457 |

| GFS | 0.031 | 0.056 | 0.119 | 0.163 | 1.032 | 1.057 |

| Depression | 0.313 | 0.039 | 0.208 | 0.235 | 1.367 | 1.040 |

| Anxiety | −0.202 | 0.325 | 0.204 | 0.295 | 0.817 | 1.384 |

| Stress | −0.038 | −0.108 | 0.177 | 0.229 | 0.963 | 0.898 |

| Burn1 | 0.807 ** | 0.884 ** | 0.318 | 0.388 | 2.241 | 2.420 |

| Burn2 | 0.053 | 0.095 | 0.072 | 0.089 | 1.054 | 1.100 |

| Burn3 | 0.334 | 0.069 | 0.212 | 0.475 | 1.397 | 1.071 |

| Age | −0.002 | −0.037 | 0.025 | 0.033 | 0.998 | 0.964 |

| Sex (female) | −0.627 | −1.170 * | 0.534 | 0.635 | 0.534 | 0.310 |

| Education (Msc) | 0.608 | −0.621 | 0.501 | 0.608 | 1.836 | 0.538 |

| Education (Phd) | 2.170 ** | −0.170 | 0.857 | 1.212 | 8.757 | 0.843 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Asderaki, F.; Milienos, F.S.; Rentzios, C.; Mastrokoukou, S.; Karagiannopoulou, E. Ready or Not? Greek K-12 Teachers’ Psychological Readiness for Bringing the EU into the Classroom. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1474. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111474

Asderaki F, Milienos FS, Rentzios C, Mastrokoukou S, Karagiannopoulou E. Ready or Not? Greek K-12 Teachers’ Psychological Readiness for Bringing the EU into the Classroom. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1474. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111474

Chicago/Turabian StyleAsderaki, Foteini, Fotios S. Milienos, Christos Rentzios, Sofia Mastrokoukou, and Evangelia Karagiannopoulou. 2025. "Ready or Not? Greek K-12 Teachers’ Psychological Readiness for Bringing the EU into the Classroom" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1474. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111474

APA StyleAsderaki, F., Milienos, F. S., Rentzios, C., Mastrokoukou, S., & Karagiannopoulou, E. (2025). Ready or Not? Greek K-12 Teachers’ Psychological Readiness for Bringing the EU into the Classroom. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1474. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111474