Philosophical Inquiry with 5–7-Year-Olds: ‘My New Thinking Friends’

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Early Education (3–7) in England

- Communication and language;

- Personal, social, and emotional development;

- Physical development;

- Literacy;

- Mathematics;

- Understanding the world;

- Expressive arts and design.

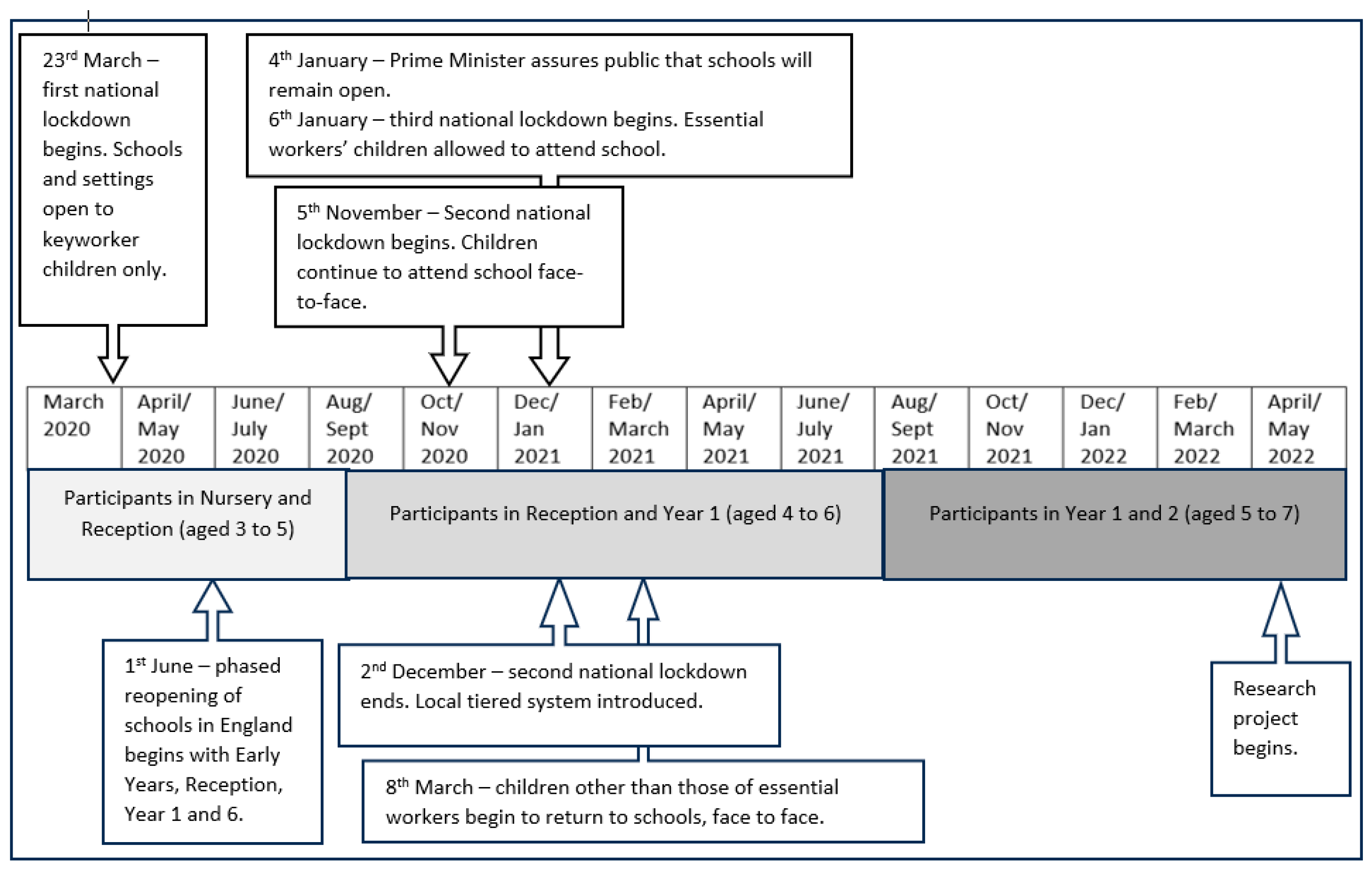

1.2. Community, COVID-19, and Impact on Children

1.3. Philosophical Inquiry with Children

- How do children express their social interaction and communication in this community of inquiry over 6 weeks?

- What are the benefits and challenges of philosophical inquiry sessions in this context?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. The Researcher/Facilitator

2.3. Mosaic Approach Methodology

- The lack of generalizability of both the methods and findings, particularly as Mosaic is often used in one setting;

- The large amount of time required to conduct Mosaic approach research;

- The cost of technological devices used in the research;

- The need for researchers to be skilled at interacting with young children.

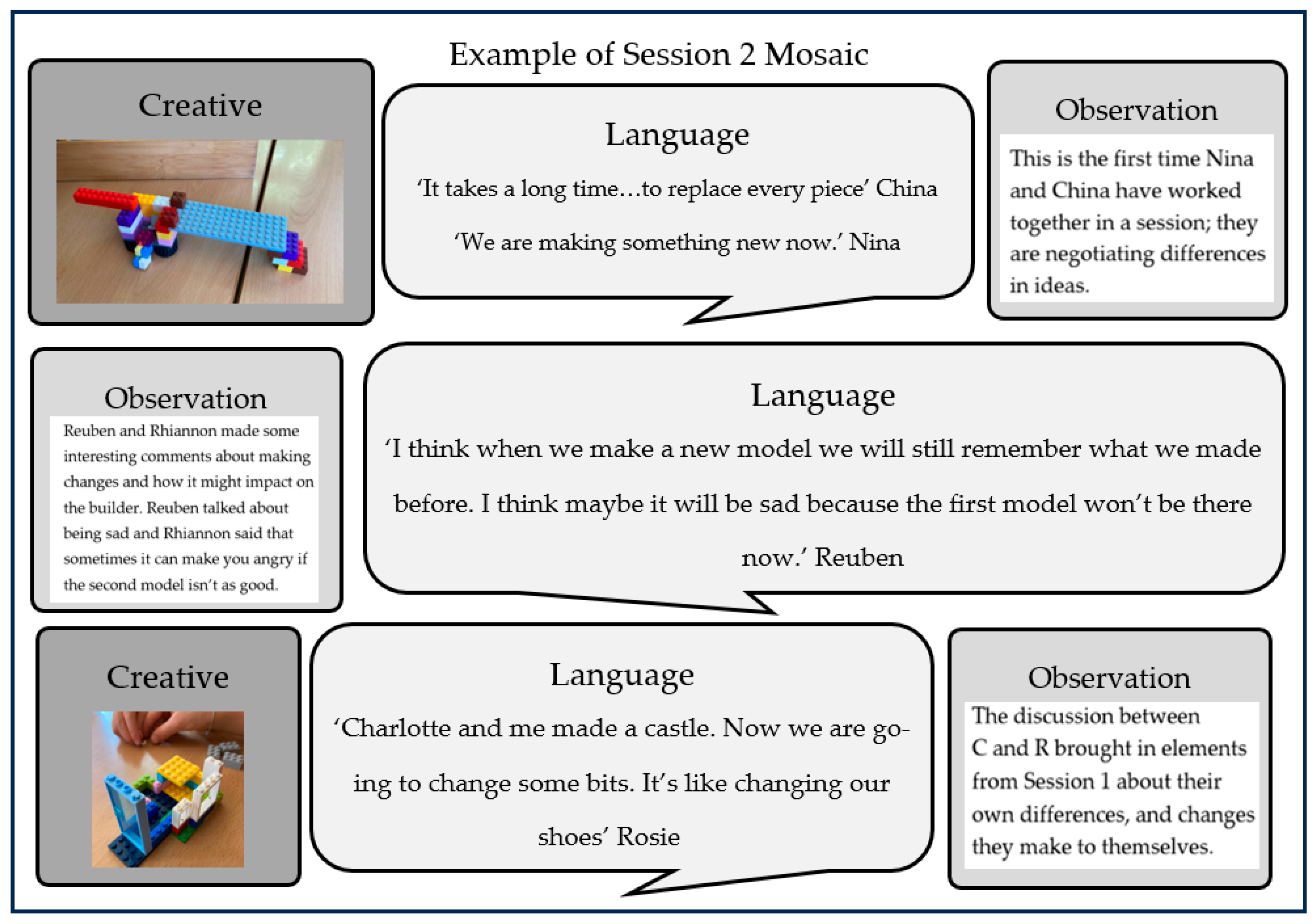

2.4. Stage 1: Gathering Data

2.4.1. Creative and Visual Methods

2.4.2. Observation

2.4.3. Language-Based Methods

2.5. Stage 2: Piecing Together Information for Discussion and Reflection

2.6. Stage 3: Interpreting the Data and Using It to Make Decisions

2.7. Participants

2.8. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Session 1: All About Me: What Makes Me Special, What Makes Us the Same

| Observations of the Session—Researcher |

| In the first session, children seemed excited, but perhaps a little confused about what Philosophy Club might be about. The walk from the classroom to the ‘club room’ provided a few minutes of transition. |

| The theme of identity—children all contributed to ideas about what we have in common and what is different—specific examples were shared. All children listened to each other. There were some notable allegiances in the group—Reuben and Jack, Belle and Rosie—who were more likely to agree with each other, and build on each other’s ideas. |

| The children were used to working in the same class as each other, so I was the only ‘stranger’ to the group. There were some clear friendships within the group (e.g., Reuben and Jack, Belle and Rosie) and these pairs of children were more likely to agree with each other, nod at the other’s contributions and build upon what their friend had said, rather than starting a new topic. |

| Even though this was a first session, some challenging topics were raised, physical disability, death of loved ones and pets. I was mindful of allowing the children to explore the discussion, but was also ready to ‘step in’ if anyone seemed upset by the discussion. |

| Rosie was probably the dominant speaker in this session, although all children contributed verbally and creatively. |

| Observations of the Session—Children |

| Everyone did good thinking today. Jack |

| I liked drawing me and talking. I think we should do this again but maybe for longer next time. Charlotte |

| You have good pens. That made the drawing much better. China |

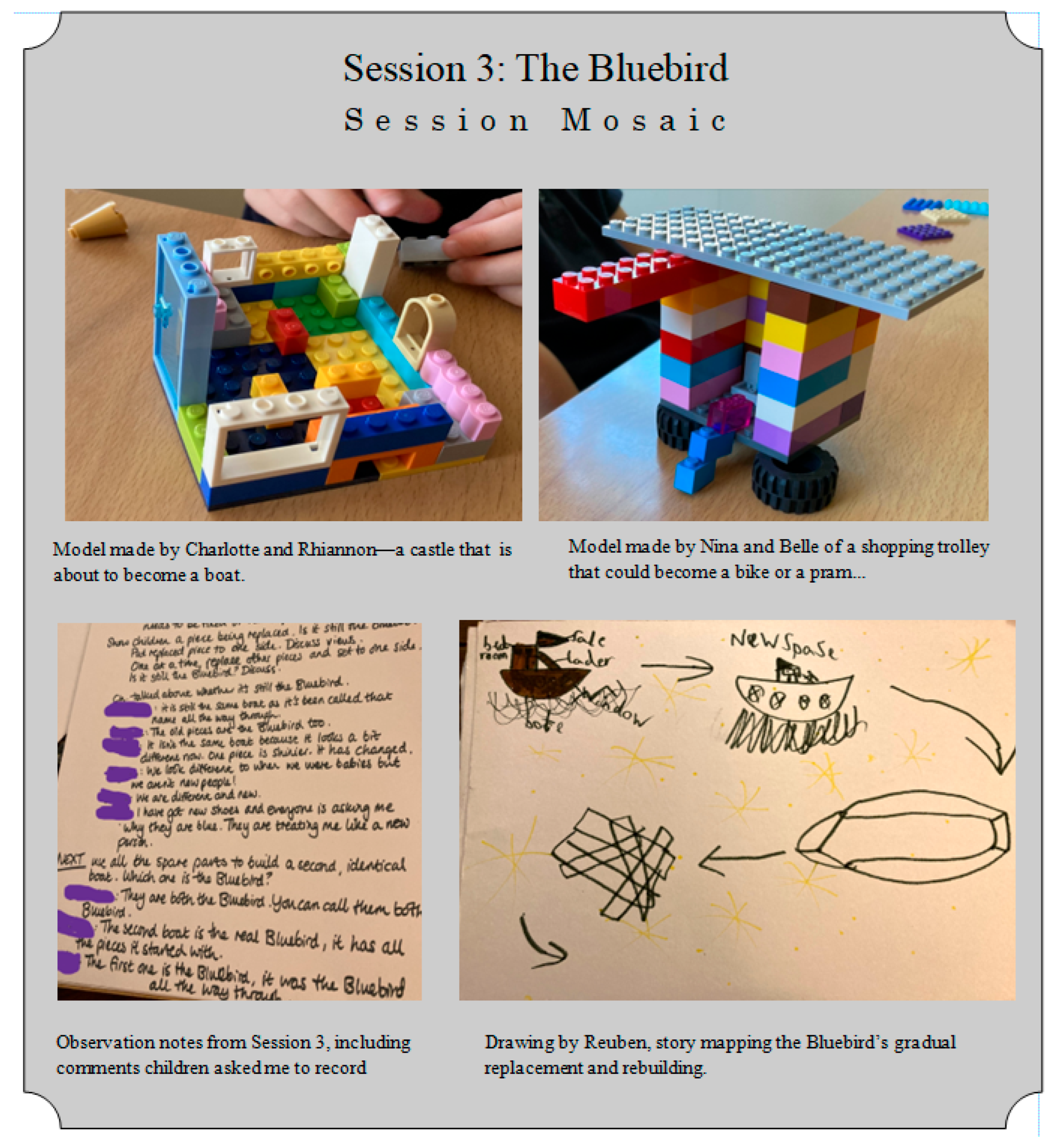

3.2. Session 3: The ‘Bluebird’—Building a New Boat

| Sample of Observations of the Session—Researcher |

| Some friendships now allow for disagreement—Belle and Rosie—and some children are chosing to work with others when building models. |

| Disagreements have been respectful. Children have had opposite views about the Bluebird, and have been able to offer explanations and examples from their own experience, but no one has suggested anyone else is wrong. |

| The children had many more differences of opinion in this session than they had in Sessions 1 and 2, and the allegiances of friendship seemed to have less influence on opinions than they might have in Session 1, for example Belle and Rosie, who in this session were comfortable to disagree with each other. |

| Reuben, who was more quiet in Session 1 and 2, now seems to offer views that the majority of the group support. There is some evidence of children changing their opinion after listening to others, will watch out for this in future sessions. |

| Observations of the Session—Children |

| I liked changing our model around. We worked together pretty good. Charlotte |

| Can you write down what we said about the Bluebird? I think my mum would like to read that. Rhiannon |

| I have my new thinking friends now. I didn’t know Jack and Reuben had so many ideas. Belle. |

- Summary of Analysis: Session 2

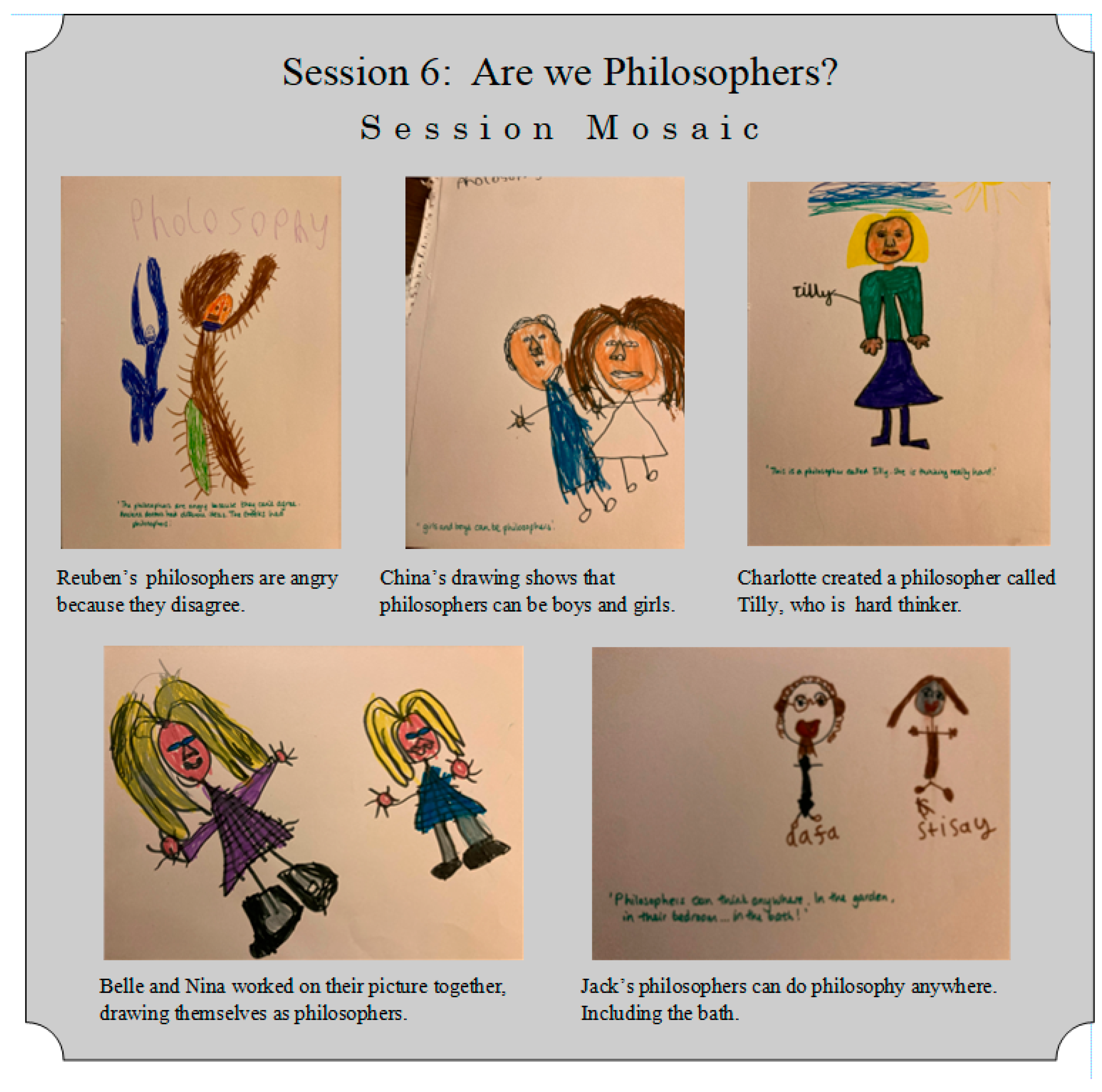

3.3. Session 6: Are We Philosophers?

| Sample of Observations of the Session—Researcher |

| Session 6 was interesting, as there were fewer opportunities for differences of opinion, perhaps—none of the children felt they were not philsophers, for example. Some differences came up around what philosophers do. It was interesting that some children had been talking about this at home. |

| The dynamics of the group feel quite different from Session 1—this might be because they are more used to me being around, but the children seem more comfortable with disagreement and less likely to conform to friendship allegiances… although it could be that they would do this in other contexts anyway, and Philosophy Club has brought about the change in their behaviour at the start. |

| Observations of the Session—Children |

| Did you write that down, Dr. Q? China |

| I think everyone has got better at drawing. I like looking at the philosophers. Charlotte |

3.4. Summary of Analysis: Sessions 1–6

- How do children express their social interaction and communication in this community of inquiry over 6 weeks?

4. Discussion

- How do children express their social interaction and communication in this community of inquiry over 6 weeks?

- What are the benefits and challenges of philosophical inquiry sessions in this context?

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Details of the Session Organisation and Topics

Appendix A.1.1. Procedure for Sessions

- Play a game with a community objective; for example, a game that builds listening skills, turn taking and noticing.

- Share the inquiry question and give children time to think.

- Thinking with a friend—share your ideas with a partner, and use Lego, clay, drawings to support thinking.

- Share ideas and creations with the group.

- Make connections between ideas—are some the same? Are some different?

- Conclude the session with a summary of the discussion.

Appendix A.1.2. Broad Session Themes

References

- Baird, K. (2013). Exploring a methodology with young children: Reflections on using the Mosaic and Ecocultural approaches. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 38(1), 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, A. E. (2023). Understanding children’s object choice and play in an outdoor setting: The embedded learning and meaning of playing with sticks [Ph.D. Thesis, University of British Columbia]. Available online: https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0438556 (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- BERA (British Education Research Association). (2018). Ethical guidelines for educational research (4th ed.). British Educational Research Association. Available online: https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018-online (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Brown, J., & Kara, H. (2025). From the mosaic approach to cultural probes: Why research improves when participants can choose. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 33, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C. (2021). Navigating young children’s friendship selection: Implications for practice. International Journal of Early Years Education, 31(2), 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C., & Nutbrown, C. (2016). A pedagogy of friendship: Young children’s friendships and how schools can support them. International Journal of Early Years Education, 24(4), 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, C., & Christie, D. (2013). Philosophy with children: Talking, thinking and learning together. Early Child Development and Care, 183(8), 1072–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, C., Marwick, H., Deeney, L., & McLean, G. (2018). Philosophy with children, self-regulation and engaged participation for children with emotional behavioural and social communication needs. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 23(1), 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, C., & Mohr Lone, J. (2020). Thinking about childhood: Being and Becoming in the World. Analytic Teaching and Philosophical Praxis, 40(1), 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cattan, S., Farquharson, C., Krutikova, S., McKendrick, A., & Servilla, A. (2023). Almost half of children saw their social and emotional skills worsen during the pandemic—And economic turbulence played a role. Institute for Fiscal Studies Report. Published on 1 August 2023. Available online: https://ifs.org.uk/news/almost-half-children-saw-their-social-and-emotional-skills-worsen-during-pandemic-and-economic (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Clark, A. (2001). How to listen to very young children: The mosaic approach. Child Care in Practice, 7(4), 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A. (2005). Ways of seeing: Using the Mosaic approach to listen to young children’s perspectives. In A. Clark, A. T. Kjørholt, & P. Moss (Eds.), Beyond listening (pp. 11–28). Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A., & Moss, P. (2005). Spaces to play: More listening to young children using the Mosaic approach. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A., & Moss, P. (2011). Listening to young children: The mosaic approach (2nd ed.). National Children’s Bureau. Available online: https://www.ncb.org.uk/resources/all-resources/filter/early-years/listening-young-children (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Department for Education (DfE). (2013). The national curriculum in England: Key stages 1 and 2 framework documents. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-primary-curriculum (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- DfE. (2021). Statutory framework for the Early Years Foundation Stage. Department for Education.

- DfE. (2022). Early Years Foundation Stage profile 2023 handbook. Department for Education.

- DfE. (2025). School admissions (webpage). Department for Education. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/schools-admissions/school-starting-age (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Egan, S. M., Pope, J., & Moloney, M. (2021). Missing early education and care during the pandemic: The socio-emotional impact of the COVID-19 crisis on young children. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorard, S., Siddiqui, N., & See, B. H. (2017). Can ‘Philosophy for Children’ improve primary school attainment? Journal of Philosophy of Education, 51(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, E., Quick, L., & Buchanan, D. (2023). National curriculum and assessment in England and the continuing narrowed experiences of lower-attainers in primary schools. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 55(5), 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayati, M., & Ghaedi, Y. (2009). Effects of the philosophy for children program through the community of inquiry method on the improvement of interpersonal relationship skills in primary school students. Childhood & Philosophy, 5(9), 199–217. [Google Scholar]

- Höpfner, E., & Promberger, M. (2023). The elephant in the room-recording devices and trust in narrative interviewing. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22, 16094069231215189, (Original work published 2023). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, D. (2022). Doing philosophy with young children: Theory, practice, and resources. Early Child Development and Care, 192(1), 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipman, M. (2011). Philosophy for Children: Some assumptions and implications. Ethics in Progress, 2(1), 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, R., & Randall, V. (2023). Enabling dialogic, democratic research: Using a community of philosophical enquiry as a qualitative research method. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 37(8), 2186–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merewether, J., & Fleet, A. (2014). Seeking children’s perspectives: A respectful layered research approach. Early Child Development and Care, 184(6), 897–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murris, K. (2000). Can children do philosophy? Journal of Philosophy of Education, 34(2), 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C., Devitt, A., & Hayes, N. (2022). Critical thinking in the preschool classroom—A systematic literature review. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 46, 101110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S., Mo, Y., & Kim, N. (2024). Exploring young children’s self and others: Integrating visual diaries and the digital emotional expression application in art education. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 33(4), 595–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, C., & Bertram, T. (2021). What do young children have to say? Recognising their voices, wisdom, agency and need for companionship during the COVID pandemic. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 29, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, C., Bertram, T., Cullinane, C., & Holt-White, E. (2020). COVID-19 and social mobility impact brief #4: Early years. Sutton Trust. Available online: https://www.suttontrust.com/our-research/covid-19-and-social-mobility-impact-brief/ (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Pillow, W. (2003). Confession, catharsis, or cure? Rethinking the uses of reflexivity as methodological power in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 16(2), 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quickfall, A. (2019). Philosophy and learning to think in OGIER, S. (Editor) A broad & balanced curriculum in primary schools: Educating the whole child. Learning Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Quickfall, A., Wood, P., & Clarke, E. (2022). The experiences of newly qualified teachers in 2020 and what we can learn for future cohorts. London Review of Education, 20(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M., & Boyd, W. (2020). Meddling with mosaic: Reflections and adaptations. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 28(5), 642–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevón, E., Mustola, M., Siippainen, A., & Vlasov, J. (2023). Participatory research methods with young children: A systematic literature review. Educational Review, 77(3), 1000–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, N., Gorard, S., & See, B. H. (2017). ‘Non-cognitive impacts of philosophy for children’ (Project Report). School of Education, Durham University. [Google Scholar]

- Tolmie, A., Topping, K., Christie, D., Donaldson, C., Howe, C., Jessiman, E., & Thurston, A. (2010). Social effects of collaborative learning in primary schools. Learning and Instruction, 20, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topping, K., & Trickey, S. (2007). Impact of philosophical enquiry on school students’ interactive behaviour. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 2(2), 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, L., Bowyer-Crane, C., Bonetti, S., Nielsen, D., D’Apice, D., & Compton, S. (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children’s socio-emotional wellbeing and attainment during the reception year (Research Report). Education Endowment Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- United Kingdom Research & Innovation (UKRI). (2025). Research with children and young people (webpage). UKRI. Available online: https://www.ukri.org/manage-your-award/good-research-resource-hub/research-with-children-and-young-people/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Urbina-Garcia, A. (2020). Young children’s mental health: Impact of social isolation during the COVID-19 Lockdown and effective strategies. Available online: https://osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/g549x_v1 (accessed on 1 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). (2025). Considering the impact of COVID-19 on children webpage. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/activities/considering-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-children (accessed on 1 September 2025).

| Pseudonym | Age | Gender |

|---|---|---|

| Reuben | 7 years 3 months | Male |

| Charlotte | 6 years 0 months | Female |

| Rhiannon | 5 years 11 months | Female |

| Jack | 7 years 2 months | Male |

| Nina | 7 years 0 months | Female |

| Belle | 6 years 11 months | Female |

| China | 6 years 5 months | Female |

| Rosie | 6 years 11 months | Female |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quickfall, A. Philosophical Inquiry with 5–7-Year-Olds: ‘My New Thinking Friends’. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1410. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101410

Quickfall A. Philosophical Inquiry with 5–7-Year-Olds: ‘My New Thinking Friends’. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1410. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101410

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuickfall, Aimee. 2025. "Philosophical Inquiry with 5–7-Year-Olds: ‘My New Thinking Friends’" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1410. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101410

APA StyleQuickfall, A. (2025). Philosophical Inquiry with 5–7-Year-Olds: ‘My New Thinking Friends’. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1410. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101410