1. Introduction

In times of increasing digitalization, it is important that schools keep pace with this societal development. Digitalization in schools can contribute to expanding students’ digital competencies and positively influence instructional practice in the long term by enabling teachers to create diverse and adaptable learning environments. However, this requires the transformation of teaching and the school as a whole organization (

Hillmayr et al., 2020). This understanding is also increasingly reflected in scientific research. Issues relating to school development are becoming an increasingly important part of the discourse on digitalization in educational science (

Heinen & Kerres, 2017). Our study aims to contribute to this focus by further exploring the subject of digital school development. To describe this multifaceted developmental process, several models have been proposed:

Digital school development. In Germany, the five dimensions of digital school development by

Eickelmann and Gerick (

2017) are frequently applied in the analysis of digital school development (

Hasselkuß et al., 2022;

Labusch et al., 2020). The model builds on

Rolff’s (

2023) existing school development model but includes two additional dimensions:

technological and cooperative development, which places a focus on school development in the context of digitalization. The five dimensions can be described as follows:

(1)

Professional development in the field of education refers to the enhancement of teachers’ professional abilities through various forms of in-service teacher training focusing on the utilization of digital media and technologies. (2)

Organizational development addresses the development of school structures and processes within the educational organization.

Eickelmann and Gerick (

2017) emphasize that a clear strategic direction and support of teachers from the school leadership teams are key factors for the success of digital school development from an organizational perspective. This also includes the establishment of digital concepts and guidelines that regulate the use of digital media. (3) The concept of

instructional development focuses on the integration of digital media into the teaching and learning process. This dimension includes the development of instructional approaches and integration of digital media in the classroom (

Fischer et al., 2015;

OECD, 2015;

Schaumburg, 2018). (4)

Technological development refers to the maintenance of the necessary technical infrastructure within the school, which is, according to

Eickelmann and Gerick (

2017), a prerequisite for successful digital school development. (5)

Collaboration focuses on the development of collaboration within the teaching staff, with external partners, and across hierarchies, including supportive collaboration by the school leadership team (

Hasselkuß et al., 2022).

These five dimensions of digital school development can be linked to other models of digital school development, such as the innovative digital school model (IDI) by

Ilomaki and Lakkala (

2018). This internationally utilized model differentiates various elements, illustrated as rooms in a house, which are here presented along the five dimensions of digital school development, as described previously: (1)

Professional development: The IDI includes this dimension into the category of “school-level knowledge practices”. (2)

Organizational development: corresponding aspects of the dimension are evident in two categories, the “vision of the school” and “leadership”, respectively. (3)

Instructional development includes the category “pedagogical practices”. When digital resources are utilized school developmental processes, the dimension (4) comprehensively addresses all the relevant aspects of

technological development of digital technology for school development. (5)

Teacher collaborations: the room “Practices of the teaching community” and parts of the category “leadership” as the IDI refers to the networking of the principal as part of the category “leadership” and can be linked to the dimension of collaboration.

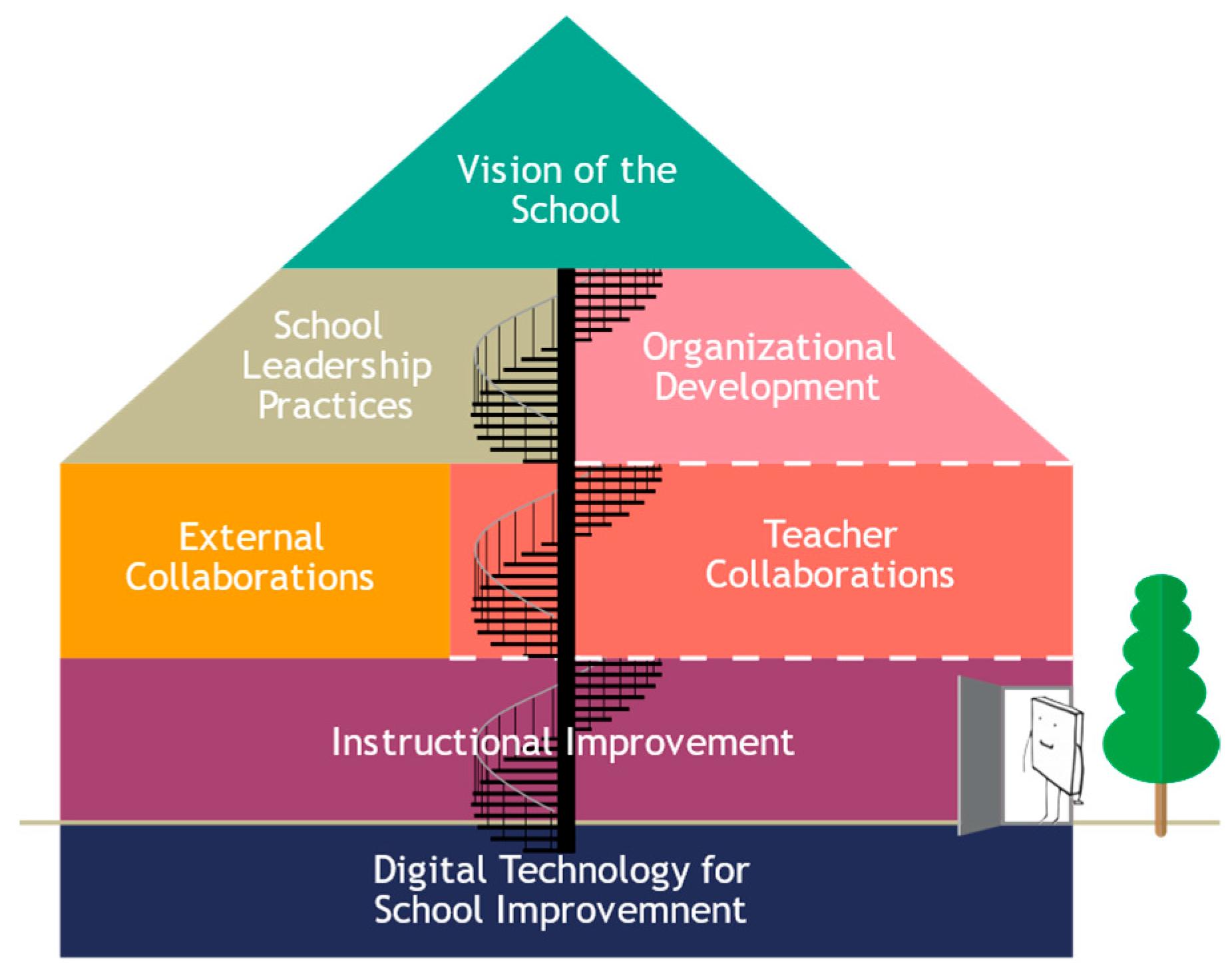

These two models provided the background for our integrated model, called the “KoKon house model”, as shown in

Figure 1.

Our model synthesizes key elements from both approaches, translating them into a practice-oriented framework which is focused on organizational processes. The KoKon house model is based on the IDI house structure. Various subcategories are represented as rooms in a house, including school vision, school leadership practices, organizational development, external collaboration, teacher collaboration, instructional development, and digital technology for school development. Moreover, to symbolize interactions across all categories of the areas of school development, we added a staircase representing the overall organizational learning in the school. This conceptualization considers school development from the perspective of organizational processes and the overall development of the institution, while incorporating all previously described areas—the rooms of the house. This conceptualization examines school development from the perspective of organizational processes and the development of the whole institution-all the described rooms of the house. An example of this perspective is the way personnel development is captured in the model.

Eickelmann and Gerick (

2017) treat personnel development as one of the five dimensions of digital school development. In our model, it is understood as a sub-category of organizational development. Therefore, the focus in our model is similarly less on depicting the individual advancement of each teacher and more on identifying the organizational practices and frameworks established for personnel development.

Compared to other models, the KoKon house model has the advantage of treating school leadership practices as a core element of digital school development. The staircase metaphor illustrates the reciprocity of leadership practices, connecting all aspects of digital school development with leadership practices. This emphasizes their general significance. Therefore, our model allows for a closer look at leadership practices to comprehend the processes and relationships involved in digital school development. As the consideration of leadership practices as a central dimension of school development and its connection to the other relevant dimensions has so far rarely been emphasized in other models of digital school development, our model serves as a basis for our study. By examining the connection patterns of school leadership teams, which are conceptualized in the model as part of leadership practices, we seek to further address this research gap (

Schäfer et al., 2024).

Leadership practices. To describe leadership practices in the context of digital school development, various models exist:

As one conceptual framework the model proposed by

Huber (

2022) outlines key leadership dimensions relevant to school development. The framework delineates a range of responsibilities, including the fostering of continuous professional development for teaching staff and the promotion of collaboration. It also describes tasks associated with the implementation of digital technologies in school administration and management as areas of responsibility for school leadership teams (

Huber, 2022). In addition to

Huber’s (

2022) model, the leadership practices that set directions for IT conceived by

Dexter (

2018) can be considered in the context of digital school development and the focus on leadership practices.

Dexter (

2018) distinguishes between three key functions of practices for leadership of IT in schools: (1) setting directions, (2) developing people and (3) developing the organization. (1) The key function of setting directions refers to the identification of a shared vision, the creation of a shared meaning, the development of expectations and performance monitoring, and the communication of the vision and goals. (2) The second key function, developing people, summarizes the leadership practices of harnessing the power of individuals, developing groups of teachers, and leading by example. The third key function, (3) developing the organization, encompasses the leadership practices of building a culture of collaboration, structuring the organization, allocating resources, and connecting to the wider environment.

The dimensions of leadership in the context of school development, as outlined by

Huber (

2022), and the leadership practices, described by

Dexter (

2018), emphasize close collaboration between school leader, teaching staff, and essential stakeholders as a key function. Setting directions, the first key function defined by

Dexter (

2018), emphasizes leadership practices that capture the joint process of developing goals. These include jointly formulating concrete goals and ensuring transparency through close collaboration with teaching staff. The second key function, staff development, incorporates close collaboration to involve all teachers in the school development process. School leadership teams must have comprehensive knowledge of the individual strengths of teaching staff to promote them effectively. The practices summarized by

Dexter (

2018) in the third function also accentuates the importance of collaborating and networking with teaching staff and other stakeholders when implementing the practices. The model outlines specific practices that can be employed to foster a collaborative culture. The practical implementation of leadership practices, which require close networking and direct collaboration with the teaching staff and individual key actors, suggests that school leadership team’s ability to exercise leadership practices depends on (their) functioning connection patterns. Research indicates that the collaboration between school leadership team and other key actors plays an especially important role for school development (

Capaul, 2021;

Prasse, 2012).

Key actor(groups) in the context of digital school development. Since previous research has not yet provided insights into the connection patterns of school leadership teams and their connection to other key actors in the context of digital school development, this study seeks to address this gap. Hereby, we examined connection patterns at schools in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

In North Rhine-Westphalia, school leadership teams which includes the principal, the deputy principal, and the extended leadership team, plays a significant role in school development. Extended school leadership team includes lower, middle and upper school level coordinators, as well as the so-called head of teaching and learning, who is responsible for coordinating instructional work as well as providing pedagogical guidance to teachers (

Qualitäts- und UnterstützungsAgentur-Landesinstitut für Schule, 2020). The tasks described by

Huber (

2022) highlight the wide range of requirements that school leadership teams will encounter when it comes to digital school development. Against this backdrop, collaboration with other relevant stakeholders could be crucial (

Prasse, 2012).

Operating as facilitators of their school’s digital transformation, digital coordinators participate in developing teaching and learning in a digital world. Their responsibilities primarily include supporting teachers using digital media in their classroom activities. These responsibilities are to be defined annually in close consultation with the school leader or the school leadership team, which already indicates close collaboration between the two key players (

Ministerium für Schule und Bildung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen, 2022).

Connection patterns of the school leadership team. To examine the connection patterns of school leadership teams, we conducted social network analyses at schools. In our study, social network analysis cannot only be understood as an evaluation method; it also forms the conceptual framework of our investigation. Social network analysis can be used to analyze relationships between different actors and to locate individual actors within groups. Hereby the focus lies on their connection to each other. In the context of school development, social network analysis can offer various advantages: it offers insights into flows of information within groups of people. Additionally, social network analysis can be used to identify key actors, analyze relationships between them, diagnose dysfunctions and gaps and raise awareness of social relationships within groups of actors (

Daly, 2012). For these reasons, the method is suitable for analyzing school leadership teams’ connection patterns. It maps their contacts and information flows, while also embedding the school leadership team within the social structure of the entire teaching staff. Because of its various applications the method of social network analysis has been increasingly used in educational research in recent years (

Grunspan et al., 2017;

Hasselkuß et al., 2022;

Kolleck & Schuster, 2019). The focus was primarily directed to student level, but teachers’ connections were also analyzed using this method (

Daly, 2012;

Schuster et al., 2021;

Wentzel et al., 2014). Individual studies have already examined the social networks of school leaders with this method.

Spillane and Kim (

2012), for example, investigated the network positions of school leaders within teaching staffs’ instructional advice and information networks by using a social network analysis. The study provides initial insights into the connection patterns of school leaders. They demonstrate that not only school leaders occupy an important role in this information networks but also individuals in other formal leadership roles hold relevant positions (

Spillane & Kim, 2012). While the study addresses the network positions of school leaders, the connection patterns of school leadership teams in the context of digital school development remain unexamined. Given the importance of connection patterns for leadership practices, the need for systematic research on this issue becomes evident. A more refined understanding of the connection patterns of school leadership teams, together with insights into relevant partners, can advance our understanding of leadership practices. This understanding facilitates the development of practical implications for digital school development (

Schuster et al., 2021).

Research questions: In order to address the existing research gap and gain a deeper understanding of the connection patterns of school leadership teams, this study will explore the following two research questions:

How are the connection patterns between the school leadership team and the teaching staff structured in the context of digital school development?

How are the connection patterns between the school leadership and the teaching staff structured in comparison to the connections of the digital coordinator?

3. Results

3.1. Networks of the School Leadership Teams in the Different Schools

To answer the first research question, which aims to examine the connection patterns of school leadership teams

Table 1 provides an overview of the average network metrics, with further disaggregation into the metrics of each school. The digital coordinator of school 9 did not participate in the survey, therefore the network metric

path length could not be determined for this school.

The descriptive statistics (

Table 1) of the average network metric of individual schools illustrates first results. The network metric of

closeness centrality shows descriptive differences between the mean values of the school leadership teams across different schools. This observation also applies to the network metric of

authority. More detailed insights into the differences between the schools can only be obtained through the visual analysis facilitated by the quartile segmentation (e.g.,

Figure 2). In contrast, the descriptives of the network metric

path length indicated that none of the average values is greater than or equal to two, which refers to the similarity in the average

path length from the school leadership team to the digital coordinator across all schools. As previously mentioned, the digitalization coordinator from School 9 did not participate in the survey; therefore, the analysis of this network metric includes only 12 schools.

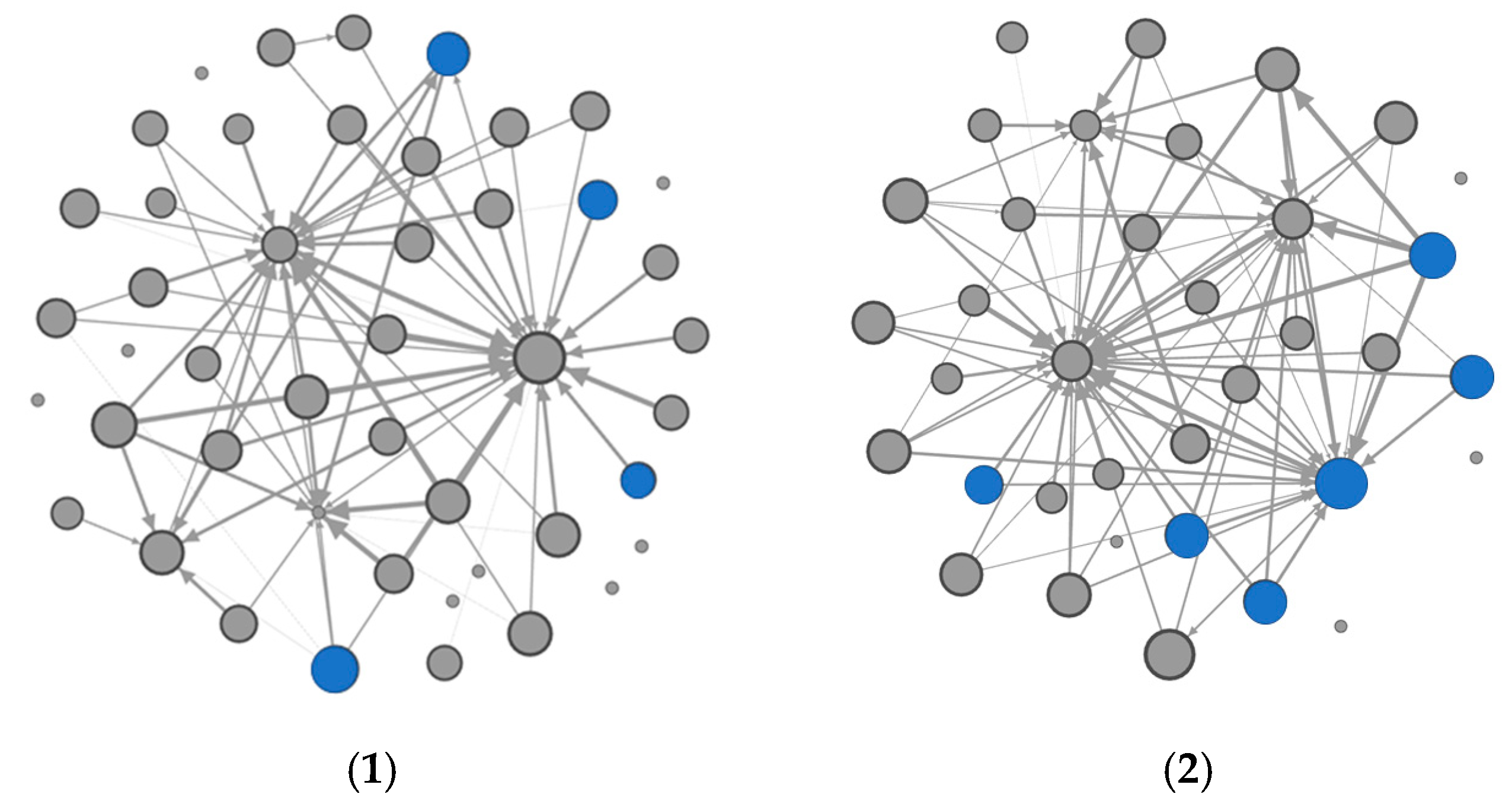

The leadership’s social embeddedness is operationalized by the network metric

closeness centrality as shown in the following

Figure 2. The division into quartiles highlights both differences and similarities in the network metric across the individual schools.

The results show that school leadership teams vary considerably in terms of their closeness centrality. The average closeness centrality of school leadership teams ranges from 0.342 (0.344) to 0.845 (0.120). The majority of school leadership teams demonstrate an average closeness centrality that falls within the second and third quartiles. The values for Schools 2 and 4 are both situated in the upper quartile. By contrast, the leadership team of school 6 displays a comparatively low closeness centrality (0.342).

Figure 3 depicts the social networks of schools 2 and 1, which illustrate the social networks of the teaching staff of both schools. The blue nodes represent members of the school leadership teams. The size of the nodes indicates the individual

closeness centrality of each node. The larger a node, the higher its

closeness centrality. It can be seen that within the school leadership team, the nodes vary in size. When comparing the size of these nodes with those representing individual members of the rest of the teaching staff, it can be seen that the nodes of the school leadership teams are relatively large.

Comparing the participating 13 schools, the average

authority value of the school leadership teams diverges between 0.000 and 0.168. The result can be seen in

Figure 4, where the average

authority values of the different schools are structured in quartiles. Across different schools, it is evident that the average

authority of school leadership teams varies across different schools across the four quartiles. This implies that the direct contacts of school leadership team members are interconnected to varying

degrees. The average

authority of school leadership teams across different schools ranges from 0.00 (0.000) to 0.168 (0.325). The majority of school leadership teams have an

authority value within the first and second quartiles. The proportion of schools whose leadership exhibits very low

authority value is relatively high. Notably, School 6 stands out due to its exceptionally low

authority of 0.00 (0.000). Additionally, Schools 1, 3, and 12, which do not exhibit notably low or particularly high

closeness centrality, also display very low

authority values. Furthermore, the schools with particularly high

authority values differ from those exhibiting high values when considering the network metric of

closeness centrality.

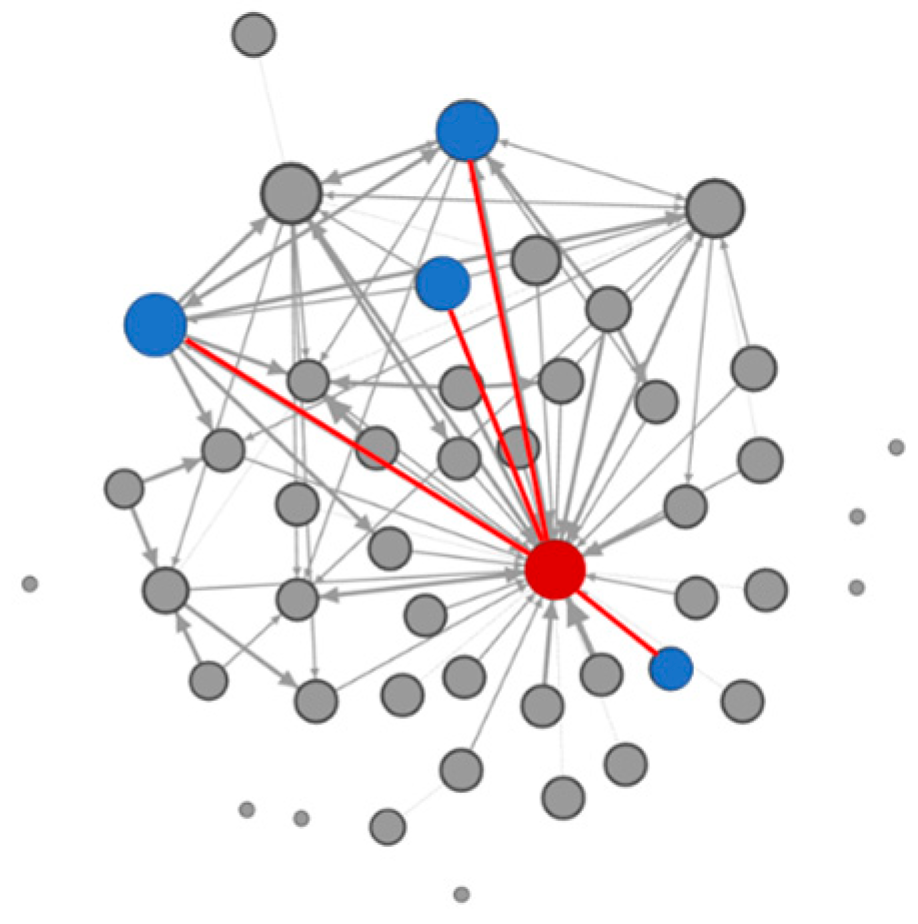

Considering the network metric path length, it becomes evident that the school leadership teams of all schools show an average path length less than two (<2). Most of the individual school leaders are directly connected with the digital coordinator.

The connection between the school leadership teams and the digital coordinator can also be seen by focusing the visual representation in

Figure 5. A school network of school 4 is shown as an example to illustrate the results. The figure illustrates the direct linkage and collaboration between the digital coordinator and the members of the school leadership team. The visualization clearly indicates that they are directly connected, with no intermediary actors present. This configuration suggests the potential for an unmediated flow of information between school leadership team and the digital coordinator. The blue nodes mark the school leadership team members, while the red node marks the digital coordinator. The connection between the school leadership team members and the digital coordinator is visualized by the red edges between them:

3.2. Networks of the School Leadership Team Compared to the Digital Coordinators

The second main research question aims to compare the connection patterns of school leadership team and digital coordinators. In order to be able to interpret the network metrics of the school leadership teams in greater detail, a comparison of the average network metrics of the school leadership teams with those of other relevant stakeholders was conducted. In the context of digital school development, the network metrics of the digital coordinator were used here. As no digitalization coordinator from School 9 participated in the survey, the subsequent analysis could include only 12 schools in the comparison.

A

t-test was conducted to compare the differences between the different stakeholders (groups). The average network metrics of the school leadership teams were compared with the ones of the digital coordinator. The results are presented in

Table 2.

The results of the t-test show that the mean score of the closeness centrality of the digital coordinator) is higher than the mean score of the closeness centrality of the school leadership teams. This difference is not significant, t(11) = −2.135, p = 0.06 (two-sided). The estimated standardized effect size for this difference is small d = 0.21, 95% CI [−1.23, 0.02]. Since the difference in closeness centrality between the actor (groups) is not statistically significant, no conclusion can be drawn regarding a higher centrality of either of the groups.

The analysis shows that the digital coordinator has a higher authority than the school leadership team at all of the twelve schools. The results of the t-test show that the mean score of the authority of the digital coordinator is higher than the mean score of the authority of the school leadership team. This difference between the mean scores of the two groups is significant t(11) = −6.531, p < 0.001 (two-sided). The estimated standardized effect size for this difference is d = 0.25, 95% CI [2.8, −0.91], indicating a small effect. This significant difference indicates that the digital coordinator’s direct network partners are more intensively connected than those of the school leadership team. Furthermore, the findings indicate that the digital coordinator is frequently approached by highly connected actors, as reflected in their extensive involvement in connections (as can be seen in the results presented for the (weighted) degree).

The results for the t-test of the network metric (weighted) degree show that the mean score of the (weighted) degree of the digital coordinator is higher than the mean score of the (weighted) degree of the school leadership team. This difference is significant t(11) = −5.507, p < 0.001 (two-sided). The estimated standardized effect size for this difference is d = 1.590, 95% CI [2.44, −0.71]. This very large effect size indicates a high difference between the groups. The observed significant difference in the (weighted) degree points to a higher degree of connection in the case of the digital coordinator. The coordinator is not only involved in a higher frequency of connections but also maintains connections (outgoing and incoming ties) with more individuals than the school leadership team.

In summary, digital coordinators do not have a significant more central network position (closeness centrality) than the school leadership. Digital coordinators exhibit a considerably higher number and frequency of direct ties (weighted degree). Furthermore, their immediate network partners also tend to engage more frequently with a broader set of actors (authority). This indicates that the digital coordinator is, overall, more strongly embedded in the network than the school leadership team.

4. Discussion

In summary, the results of the first research question show that the connection patterns of the school leadership teams in context of digital school development differ greatly between schools. Although the schools operate under similar conditions, their leadership teams reveal distinct results across the different network metrics. When examining the differences in the network metric closeness centrality among school leadership teams of the individual schools their values differ over three quartiles. Their direct contacts appear to be networked to varying degrees, as their average authority differs over all quartiles. All have in common that most individual members of the school leadership teams share a direct link to the digital coordinator. These results from the first research question must be linked with those of the second question to obtain an impression of the connection patterns of the school leadership teams by directly comparing their network metrics with those of the digital coordinator. The school leadership teams are less connected than the digital coordinators with the teaching staff of their schools. Especially in terms of their direct connections (weighted) degree, the digital coordinators have significantly higher network metric. They also appear to be more relevant, as they are contacted more frequently by other highly connected individuals, which can be inferred from their small higher authority. These key insights will be taken up and further explored in the following discussion:

The substantial variability in

closeness centrality between the different school leadership teams could be explained in several ways. One possible explanation is the individual personality types and experiential backgrounds that school leadership team members bring to their roles (

Christiansen, 2020). Another potential explanation is the availability of resources, such as the school’s software infrastructure. School leadership teams working in better-equipped schools are more accessible to the faculty and can more easily establish contact with the entire staff (

Orhani et al., 2024).

Considering the results of the network metric

authority, it can be stated that the remarkable differences in the

authority of the different school leadership teams are quite unexpected.

Authority can be seen as a measure of an actor’s influence. Varying influence of school leadership teams could be attributed to both their individual leadership styles and their institutional roles, which collectively shape the influence and decision-making power of school leadership team in various digital school development issues (

Diamond & Spillane, 2016;

Schäfer et al., 2024).

The short

path length of the actors’ close network connections, which can be found in all schools, can be interpretated as an attribute to their respective functions and the responsibilities associated with their roles (

Ministerium für Schule und Bildung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen, 2022). In the course of the ICILS study, about 85% of school leaders stated that they support a joint development of a concept for the school in the context of digitalization (

Gerick et al., 2023).

It might therefore be assumed that the school leadership team would have a high value in the network metric

degree. Without direct and frequent contact, they would not be able to support this development adequately. As this expectation of a high

degree could not be supported, it can be assumed that they may only be able to perform them inadequately if they do not delegate them to other key individuals. These findings corroborate the results of previous studies, which likewise point to a central network position occupying other formally designated leadership positions outside the school leadership team. The recommendation from

Spillane and Kim’s (

2012) study, that school leaders should exercise particular caution when assigning other formal leadership positions, also applies when examining the results of our study, to the role of digital coordinators. The findings of

Prasse (

2012) emphasize that close collaboration among key stakeholders is important for digital school development. This corroborates the high network metrics of the digital coordinator identified in our study.

To conclude, the findings indicate that, despite similar contextual conditions, school leadership teams show considerable variation in their network metrics. The factors accounting for these differences remain speculative. The results of the relevance of the digital coordinator support previous studies that emphasize the relevance of other stakeholders and collaboration with them. They further demonstrate that, due to their more advantageous connection patterns, digital coordinators may in some aspects be more relevant for the process of digital school development than the school leadership team itself.

Implications for future research. To derive the implications additional outcome variables could be taken into account to obtain an insight into how the different connection patterns affect various aspects of digital school development. International comparative studies have shown that teachers in Germany tend to engage in professional collaboration less frequently, also in the context of media-related collaboration. Therefore, a similar analysis conducted in other national contexts could reveal alternative patterns of networks among teachers and school leadership teams (

Gerick et al., 2019;

Richter & Pant, 2016). From a theoretical perspective, further research could help to close the existing research gap by examining in detail how individual members of school management teams are connected to each other, and the concrete effects that well-functioning connection patterns have on the process of developing schools in their digitalization. It would therefore be advisable for future research to extend the insights of our study through the incorporation of additional variables. To be able to link the findings with concrete, practical recommendations and conditions for success of digital school development, it would also be useful to examine the specific leadership practices of the school leadership teams. In light of the findings of this study, practices that emphasize collaboration and networks of the school leadership team and digital coordinators deserve closer examination in future studies.

Practical implications. The results demonstrate the connection patterns of school leadership teams and allow for first implications for educational practice. Implications for practice that can be derived from the results and by including the results of other studies can be summarized as follows: The school leadership teams should obtain transparent information about their low network metrics. Only if school leadership teams are transparently educated about the fact that other stakeholders possess closer connection patterns can they take this into account in their daily work. The importance of the digital coordinator can thus be taken into account in the future when distributing tasks and responsibilities. In the feedback and recommendations provided to our project schools, we already take these findings into account. The recommendations encourage schools to assign greater responsibility to their digital coordinator. Our results also indicate the relevance of distributed school leadership as a potential solution. In particular, tasks and responsibilities should be delegated to other strongly networked key actors, such as the digital coordinator, to better utilize their connection patterns. Therefore, a more differentiated view of the role of school leadership team in digital school development should be considered, with a stronger focus on its connection to key stakeholders in these processes.

Limitations. While this study provides first insights into the connection patterns of school leadership teams, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations that may impact the interpretation and generalizability of the results. The generalizability of the results could be limited by small number of cases of the study (N = 13). To gain a broader understanding of school leadership teams networks in the context of digital school development, a similar study with a larger number of schools would be necessary. Another limitation to acknowledge is the potential bias that, as a result of the recruitment strategy, the participating schools are likely to be more motivated toward digital school development than schools on average. The design and framing of the network analysis may have led to the non-participation of relevant actors, potentially due to concerns regarding the protection of their anonymity. As a result, the network analysis only partially reflects the actual network structures within each school, given that approximately 30% of teachers per school did not participate. The geographical location of the schools also needs to be cited as a limitation, as it could result in a restricted consideration of (educational policy) conditions.

In order to gain further insights into the connection patterns of school leadership teams, the project schools will continue to be accompanied throughout the course of the project. In addition to specific feedback and individualized recommendations, teachers at the participating schools have the opportunity to take part in professional development programs. Furthermore, in a subsequent meeting with the schools, it is planned to evaluate our recommendations against the backdrop of their practical feasibility.