Abstract

This research explores the Kazakhstani public schools’ English language teaching (ELT) policy. Despite numerous policy reforms to enhance English language teaching (ELT) in Kazakhstani public schools, relatively little research has examined teachers’ perspectives on the interface between the top-down policy and classroom realities. Therefore, this study addresses this gap by investigating the lived experience of English language (EL) teachers from 17 regions, highlighting significant disparities in resources, training, and personnel. The findings suggest that top-down policies create a mismatch with realities at the classroom level, where training is insufficient. Resources are lacking, and ELT policy intentions have not met the real needs of the EL teachers. This paper criticises the ELT policymaking for the marginalisation of the voices of EL teachers. Instead, it advocates a more participatory approach at the bottom of policymaking, which embodies educators themselves. This paper contributes to the wider discussion on language policy by drawing attention to the role of teacher agency, emphasising contextually valid and equitable policies that would address the relevance of ELT in multilingual and resource-lacking contexts like Kazakhstan.

1. Introduction

Historically, Kazakhstan’s foreign language education (FLE) system dates back to the Soviet Union. The language policy of the Soviet Union aimed at fostering the Russian language as a foundation for the development of Soviet culture. By prioritising the Russian language throughout the USSR, Soviet ideology aimed to eliminate linguistic and cultural barriers between nationalities (Fierman, 2006). Besides that, in post-Soviet countries, the Russian language serves as the lingua franca (Zabrodskaja & Ivanova, 2021). Nevertheless, since gaining independence, the leading position of the Russian language in Kazakhstan’s linguistic landscape has gradually diminished in favour of the English language (EL) (Kirkpatrick & Liddicoat, 2019). Moreover, in the post-Soviet era, the linguistic landscape changed dramatically by promoting the Kazakh language and the emergence of English as a strategic priority, where English is now the third official language, besides Kazakh & Russian (Zhunussova et al., 2022). In modern Kazakhstan, numerous governmental programmes, such as ‘Concept of Development of Foreign Language Education in Kazakhstan’ (2006), the ‘Trilingual Education’ programme (2012), the ‘Concept for the Development of Language Policy for 2023–2029 years’ and others, were adopted to develop English language teaching (ELT) in Kazakhstani public school.

However, a common pattern unites the mentioned programmes: all are the result of top-down policies, and the voices of schoolteachers in Kazakhstan remain under-researched (Manan & Hajar, 2024). Indeed, while there is a growing body of research on English medium instruction (EMI) in Kazakhstan, for instance, Yessenbekova’s (2023) examination of EMI in Kazakhstani higher education, Tajik et al.’s (2023) insights into the potentials and barriers faced by university students and instructors, and Manan & Hajar’s (2024) study of STEM teachers’ responses to EMI policy, there remains a gap in the literature regarding the experiences of EL teachers in Kazakhstani public schools concerning ELT policies.

Therefore, this research aims to address that gap by examining the lived experiences and perspectives of EL teachers. The study seeks to fill the gap by employing the ‘bottom-up approach’ theoretical framework. This framework is particularly relevant in the context of Kazakhstan, where top-down policy approaches often overlook the agency and insights of grassroots educators. Moreover, this work’s findings have significant implications for Kazakhstan and other multilingual societies and post-Soviet countries grappling with similar challenges in education policy development.

The research questions of this study have been formulated as follows:

- How do English language teachers in Kazakhstan perceive the effectiveness of the ELT policy?

- How do these perceptions vary with their experience levels?

- What are the key challenges, from the perspective of EL teachers, that hinder the realisation of ELT in Kazakhstan?

In the following section, we discuss this study’s theoretical framework and provide a brief overview of Kazakhstan’s top-down policy and methodological details. The next section summarises the findings, followed by analysing the data and interpreting the results. The final section outlines the study’s main conclusions and limitations.

1.1. Examining ELT Policy Through the ‘Bottom-Up Approach’ Theoretical Framework

The dominance of the top-down policy emphasises the importance of assessing the current state of ELT policy in Kazakhstan from the ground perspective. When language policies are interpreted and enacted at the local level, experienced teachers frequently offer a more sceptical view of the feasibility of some policy objectives (Johnson, 2013), as they often foresee the practical limitations of ambitious policy goals (Ricento, 2006).

In Language policy and planning (LPP), the role of a teacher is often viewed as a mere executor of directives, operating under the system without questioning the policies (Shohamy, 2006). However, teachers are essential in implementing language policies (Baldauf, 2006), and as classroom practitioners, they are the ‘heart of language policy’ (Ricento & Hornberger, 1996) and mediate between top-down directives and classroom realities. This is particularly relevant in the context of Kazakhstan, where EL teachers face significant challenges in interpreting and applying ELT policies to their unique classroom contexts. Additionally, Vongalis-Macrow (2007) argues that the actions and reactions of teachers play a crucial role in determining the outcomes of educational changes. Furthermore, Baldauf & Liddicoat (2008) emphasise that local contextual factors often shape how broader macro-level plans are executed and the results they produce. Also, the experts agree that teachers, through their agency in the classroom, ultimately influence the implementation and effectiveness of language education policies (Mohanty et al., 2010).

Bandura (2001) defines agency as the ability to exert control over the nature and quality of one’s life. Baker (2005) proposes that agency is the evolving ability of individuals to act autonomously and make their own choices and decisions. Sang (2020) and Varpanen et al. (2022) have mentioned that education reforms are more likely to succeed when teachers’ professional agency is at the centre. This assertion corresponds to the third research question of this study, which examines how the lack of agency among EL teachers in Kazakhstan contributes to policy implementation challenges.

Furthermore, Chua & Baldauf (2011) argue that macro and micro planning are interdependent in effecting LPP. At the micro level, teachers are central actors who interpret and carry out policies devised at the macro level. Knowing their perceptions becomes relevant for identifying possible gaps between policy intentions and classroom realities prior to more context-sensitive and effective planning. Moreover, Martin (1999) points out that teachers are the agents who mediate policy and pupils, controlling how policies are adapted to classroom practices. These align with the study’s first and second research questions, which explore how understanding teachers’ perceptions is crucial in addressing the gap between policy intentions and practical implementation, especially in contexts where top-down approaches dominate.

What is more, significant barriers to the effectiveness of language programmes are inadequate resources, limited facilities, and institutional support. Breen (2002) adds that the school environment, including support and resources, affects the success of language programmes since the more restricted the environment is, the more severely constrained the teachers’ performance becomes. This was like the findings in Kazakhstan, where differences in resources and teacher shortages impede the implementation of ELT policy. Besides that, this corresponds to this study’s third research question, which investigates the challenges to ELT policy realisation in Kazakhstan, characterised by resource disparities and infrastructure issues.

Consequently, scholars argue that the focus of language in education policy research should shift from top-down government policies to bottom-up policy structures, emphasising the roles of local school administrators, teachers, students, parents, and community members (Menken & García, 2010, pp. 1–3; Manan et al., 2021, p. 292).

Even though practitioners are often considered an afterthought, merely implementing decisions made by experts in the government, board of education, or central school administration (Ricento & Hornberger, 1996, p. 417), teachers, as key policy actors in the field, play a crucial role in the design and implementation of any reform. Therefore, they require focused attention and support, especially from educators and policymakers (Valdiviezo, 2010, p. 75). On top of that, engaging with local actors is important because individuals like teachers possess a deeper, clearer, and more insightful understanding of language-related policies and issues at the ground level compared to policymakers (Manan & Hajar, 2024, p. 4).

Consequently, this study utilises the ‘bottom-up approach’ framework, highlighting the importance of grassroots involvement in language policy implementation. This corresponds with Ricento and Hornberger’s (1996) ‘onion model’, which stresses the multi-layered nature of language policy, from macro-level directives to micro-level classroom realities, where the teachers are pivotal actors that mediate between policy intention and practical application. Similarly, Baldauf & Liddicoat’s (2008) study on micro-planning stressed the need for incorporating the level of local actors to bridge gaps between large-scale goals and contextual realities. The findings of this study extend such theories by showing the central role of teacher agency in the multilingual context. Additionally, this study investigates the disjunction between top-down ELT policies and classroom realities and extends the understanding of how policies can be reconstituted to empower teachers worldwide. This study’s insights are particularly relevant to multilingual and resource-poor settings, where teacher agency dictates policy outcomes.

Thus, the ‘bottom-up approach’ framework shows off a flexible and integrative approach to the LPP (Baldauf & Kaplan, 2005). It deviates from the mainstream top-down, technocratic view that policymaking is a mono-directional process mainly executed by policymakers and is often ignorant of the role and impacts of local stakeholders. Menken & García (2010, p. 2) named this as ensuring the ‘agency in implementation’. This is one of the core aspects of LPP procedures that recognise that the individual actors and the institutions in place can act and bring about change (Fenton-Smith & Gurney, 2016; Giddens, 1986). In this way, this study brings up the necessity of recognising that language policy is a complex matter, including lofty layers and actors, such as local educators (Hornberger & Johnson, 2007; Ricento & Hornberger, 1996). For this reason, it is difficult to disagree that top-down approaches resulting from large-scale planning processes must be complemented by bottom-up processes, in which teachers can act as mediators of reform (Chua & Baldauf, 2011; Sang, 2020).

1.2. Top-Down ELT Policy in Kazakhstan

In Kazakhstan, the President’s Executive Office is major in formulating education strategies and developing key initiatives. The Ministry of Education and Science is responsible for creating educational policies and implementing them (OECD & The World Bank, 2015).

In 2004, starting in grade 2, the large-scale introduction to EL learning in Kazakhstani public schools began. Two years later, in 2006, headed by prominent Kazakhstani scholar Kunanbayeva, the ‘Concept of Development of Foreign Language Education in Kazakhstan’ was approved. This document describes the general strategy, goals, objectives, levels, content, and main directions of FLE in a scientific, practical, and methodological way (Kunanbayeva, 2004).

Later, one of Kazakhstan’s famous reforms in the school education sphere was the ‘Trilingual Education’ programme initiated by the Government in 2012. In this project, English was supposed to be employed as a medium of instruction alongside Kazakh and Russian. According to the project, the age for EL instruction in public schools was lowered to six. This new curriculum included 3 h of weekly EL instruction starting from grade 1 (Kambatyrova et al., 2022).

However, in 2019, the ‘Trilingual Education’ programme was paused. The reason was that according to the State Program for Education and Science Development of the Republic of Kazakhstan for the 2020–2025 period, a gradual shift to the study of individual subjects in three languages should be launched, providing teaching staff preparedness and taking into consideration parents’ and students’ attitudes (Kambatyrova et al., 2022). In other words, the Government acknowledged the unpreparedness of schoolteachers to implement the programme.

In 2022, the Ministry of Education suspended the learning of English from the first until the third grade. The authorities reasoned that it is difficult for learners to acquire three languages simultaneously. It is more reasonable to let a child acquire reading and writing in their native language first (V-Shkolakh-Kazakhstana-Anglijskij-Yazyk-Nachnut-Izuchat-S-Tretego-Klassa-, 2022). Additionally, in the same year, the Ministry adopted amendments to the English instruction curriculum: as stated in the order of the Ministry number 25, the study load for the subject ‘Foreign language (English)’ varies depending on the type of model curriculum at the primary, junior, and secondary education levels (see Table 1).

Table 1.

The study load for the subject ‘Foreign language (English)’ in Kazakhstani public schools.

Also, the content and curriculum of the Foreign language (English) programme aim to help students reach the levels corresponding to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) through a variety of tasks that promote critical thinking, analysis, evaluation, and creativity (see Table 2).

Table 2.

The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages adopted in Kazakhstani public schools.

In October 2023, the Government approved another programme, the ‘Concept for the development of language policy for 2023–2029 years’, underscoring the promotion of the Kazakh language. However, according to that programme, there is a strategic plan to increase the proportion of the population speaking Kazakh, Russian, and English. The target is to reach the ‘trilingual’ population proportion for the year 2024 at 15.5%, subsequently increasing it by 0.5% annually to reach the final target of 18% by the year 2029 (Concept for the Development of Higher Education and Science in the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2023–2029, 2023).

Every year, Kazakhstani schoolteachers receive a methodological instruction letter from the Altynsarin National Academy of Education, which outlines the educational process for grades 1–11 in educational organisations. According to the document, 2 h of English language instruction are allocated to third-grade students, while junior and secondary school students receive 3 h per week. Also, a class should be divided into two groups only when there are 24 or more students (2022–2023 oqu jilinda Qazaqstan Respublïkasınıñ orta bilim beru uyimdarindaği oqu-tärbïe procesiniñ erekşelikteri turalı. Nusqawlıq-ädistemelik xat, 2022).

Smagulova (2008, p. 448) noted that a quick penetration of English into society and the Government’s encouragement to make Kazakhstan a competitive member in the regional and world arena led Kazakhstan to implement a multilingual ideology. Furthermore, Kazakhstan is the first country in Central Asia to implement a trilingual education policy in schools and universities, delivering several subjects in three languages (Hajar et al., 2023). Moreover, according to some authors, within the framework of the theory of three concentric circles (Kachru & Smith, 2008), Kazakhstan can be classified as an expanding circle since English is a means of international communication and is a compulsory subject in higher education (Ahn & Smagulova, 2022; Akynova, 2014).

However, overloaded classes, teachers’ extracurricular workload, and limited educational resources are not rare in the country (Bokayev et al., 2020). Moreover, despite the Government’s adoption of numerous policy reforms in ELT, English proficiency in Kazakhstan is currently at a very low level. To illustrate, following the 2024 EF English proficiency index, Kazakhstan, with a score of 427 points, ranked 103th among 116 countries worldwide (EF EPI, n.d.).

One contributing factor to such a situation could be the top-down nature of policy implementation, which often involves language planning at a macro level (Taylor-Leech & Liddicoat, 2014). This approach has led to situations where teachers in Kazakhstan were not involved in the policymaking process or consulted prior to policy decisions (Manan et al., 2023). Similar to other Asian countries, educational reforms in Kazakhstan are frequently marked by a top-down methodology (Yakavets et al., 2023).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Questionnaires are useful for contacting people from large geographical areas or living in remote locations, offering easy dissemination and access (Oppenheim, 2005). Our survey encompassed all 17 regions and major cities of Kazakhstan. The focus group of the survey comprised Kazakhstani public schools’ EL teachers, a total of 743 respondents. Participants were selected based on (i) occupation (EL teachers only), (ii) teaching levels (all public school levels), (iii) experience levels (from less than a year to more than 20 years), (iv) geographical distribution (participants are from all regions), and (v) their willingness to participate voluntarily in the study.

Efforts were made to include teachers from both urban and rural areas to capture regional disparities in ELT policy implementation. Exclusion criteria included teachers from private schools or higher education institutions, non-EL teachers, and administrative staff. Although such an approach may limit generalizability, the large sample size enhances the study’s reliability.

2.2. Instrument: Structure and Content of the Questionnaire

The questionnaire was designed based on an overview of the literature on language-in-education policy and teacher agency. Constructs, such as resource adequacy and teacher perceptions of policy effectiveness, were informed by prior studies (e.g., Ricento & Hornberger, 1996; Breen, 2002).

The questionnaire (Appendix A) consisted of 30 questions divided into four sections, each aimed to gather information about a particular aspect (Table 3). The questions employed Likert scales, multiple-choice formats, and open-ended responses to gather detailed and nuanced feedback. This approach was important for capturing the essence of EL teachers’ experience in Kazakhstan’s diversified educational setting.

Table 3.

A table detailing the questionnaire and the rationale for the questionnaire design.

2.3. Procedure

We used an online questionnaire, Microsoft Forms, for the survey, which allowed us to collect data effectively. Collaborating with the Kazakhstan Teachers of English Association, we adopted a diverse distribution approach to ensure a wide target audience. The survey was disseminated through educational institutions, relevant social media platforms, and the country’s professional networks. Data collection lasted from December 2023 to March 2024.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

Confidentiality was upheld by not disclosing participants’ identities and keeping the information they provided confidential. Fundamental rights, such as the right to privacy, were guaranteed. Relevant country laws concerning these matters were safeguarded.

2.5. Data Analysis

Upon completion of data collection, data were subjected to rigorous analysis using IBM SPSS 29.0.2.0 (20). Quantitative data underwent precise analysis to display trends, correlations, and disparities using research methods like Crosstab analysis, Pearson’s correlation, and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). The choice of statistical methods was custom-made to best fit the character and structure of the questionnaire and to analyse the relationships and contrasts within the data.

Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used for continuous variables to explore the magnitude and direction of relationships between variables. Correlation coefficients were interpreted as follows: |r| < 0.3 = weak, 0.3 ≤ |r| < 0.6 = moderate, and |r| ≥ 0.6 = strong (Cohen, 2013).

In the results analysis process, the ANOVA statistical test was chosen to see if the difference between sample means across multiple groups was due to more than random chance. In addition to the ANOVA, post hoc comparisons were conducted using Tukey HSD analyses to identify specific pairs of groups of EL teachers whose positions showed significant disagreement on the issue at hand.

Using Crosstab analysis enabled us to observe how two categorical variables interact. This is a good tool for analysing questions related to geographical disparities, such as the digital divide and resource allocation. This method represented the frequency and distribution across different categories, which enhanced our understanding of regional patterns and differences in access to educational resources and Internet connection quality.

The combination of these methods helped us analyse the data exhaustively. Each method served a specific purpose according to the question type and data structure, giving our study a strong analytical framework.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results

Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics (sample size, mean and standard deviation) for key variables examined in this study. These descriptive statistics provide a foundational understanding of the dataset and highlight key areas of concern in teacher perceptions, resource availability, and the implementation of ELT policies. They set the stage for subsequent analyses, such as correlations and ANOVA, to explore relationships between these variables.

Table 4.

Sample sizes (N), means and standard deviations (SD) of variables used for data analyses.

3.2. Perceptions of ELT Policy Effectiveness

We employed Pearson’s correlation method to analyse the responses that revealed how English language teachers in Kazakhstan perceived the effectiveness of the ELT policy. This allowed us to explore relationships between teachers’ perceptions and variables such as teaching experience, resource availability, and optimism about the ELT policy’s ambitious goals.

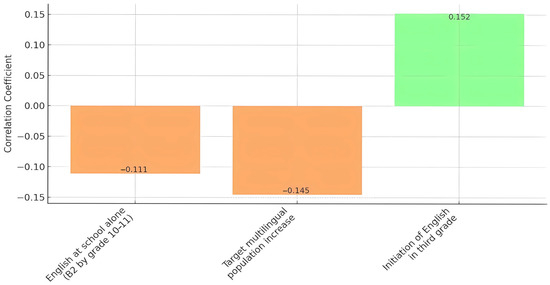

As shown in Figure 1, the results revealed a weak negative correlation (r = −0.111, p-value < 0.01) between the teaching experience of EL teachers and their view on students’ proficiency in the EL at the B2 level upon graduation. These findings imply that EL teachers with broad experience are sceptical about students’ achievement of B2 level in English by grades 10–11(12). Alternatively, this may indicate that EL teachers with less experience could be more optimistic about the effectiveness of school-based EL instruction.

Figure 1.

Correlation of variables with teaching experience of EL teachers.

The variable ‘Target multilingual population increase’ has a weak negative correlation (r = −0.145, p-value < 0.001) with the experiences of EL teachers. In other words, these findings suggest that as the experience of EL teachers increases, their confidence in the achievability of the target percentage by the Concept trilingual population (Kazakh, Russian, and English 2023—15%, 2024—15.5%, 2025—16%, 2026—16.5%, 2027—17%, 2028—17.5%, 2029—18%) decreases slightly. It may imply that teachers with solid experience in teaching English could question the effectiveness of present educational policies in achieving the ambitious trilingual language goals.

Furthermore, the analysis indicated a weak, albeit significant, correlation between teaching experience and the initiation of English learning in the third grade. There is some positive correlation (r = 0.152, p-value < 0.001) between the number of years teaching English and whether starting to learn English in the third grade (when pupils are 8–9 years old) is appropriate. This finding may indicate that EL teachers support the Ministry of Education’s decision to delay EL instruction from the first to the third grade (a policy that took effect in the 2023–2024 academic year).

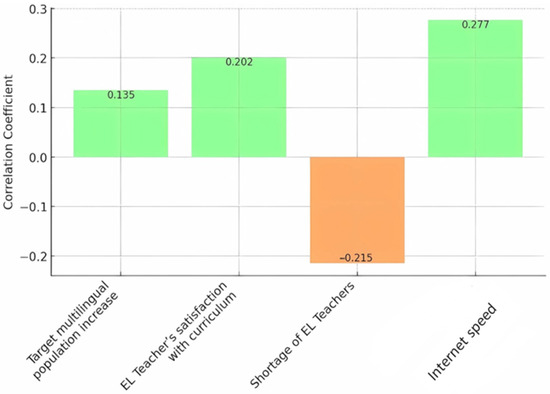

As illustrated in Figure 2, a positive correlation between the perception of the sufficiency of the school’s EL education resources and the belief that the multilingual population gradually increases, as outlined in the Concept, has been revealed. Although the correlation is relatively weak (r = 0.135, p-value < 0.001), it could be hypothesised that improving the quality and quantity of EL education resources in schools may result in a slight increase in the probability of attaining the Concept’s ‘trilingual’ targets.

Figure 2.

Correlation of variables with school resources.

Similarly, there is some positive correlation (r = 0.202, p-value < 0.001) between EL teachers’ level of satisfaction with the EL curriculum and the availability level of resources for EL education. This may indicate that as the rating of resource availability increases, there is, among EL teachers, a mild inclination towards satisfaction with the official EL curriculum.

Additionally, we observe a statistically significant, albeit weak, negative correlation (r = −0.215, p-value < 0.001) between EL teacher shortages and resource availability ratings. This may signal that improving the availability of educational resources in public schools may mitigate the shortage of EL teachers. Also, a weak positive correlation (r = 0.277, p-value < 0.001) between the adequacy of schools’ resources and Internet connection quality has been detected.

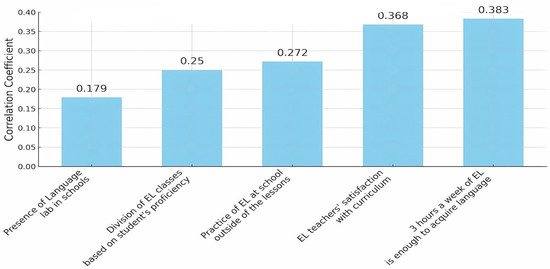

The following analysis (see Figure 3) aims to broaden our understanding of whether the objectives for the multilingual population (Kazakh, Russian, and English) outlined in the newly accepted Concept are achievable from EL teachers’ perspective by 2029.

Figure 3.

Correlation of variables with achievability of multilingual population by year 2029.

The presence of the language lab at school has a positive but weak correlation (r = 0.179, p-value < 0.001) with the belief that multilingual population targets, as outlined in the Concept, are attainable. It indicates that schools provided with language labs may be more inclined to view the goals of the Concept as achievable, possibly due to enhanced facilities for teaching EL.

Further, we found that EL teachers have shown a positive view towards meeting the goals outlined in the Concept dependent upon the division of EL classes by students’ EL proficiency levels. For example, a statistically significant weak positive correlation (r = 0.250, p-value < 0.001) was revealed between the possibility of achieving the Concept’s targets and the division of EL classes based on students’ language proficiency levels. This correlation implies that, to some extent, organising EL classes by students’ proficiency levels may influence teachers’ optimism about attaining language policy objectives.

Similarly, EL teachers may believe in the achievability of multilingual targets of the Concept if students can have additional practices to develop language, as there is a positive correlation (r = 0.272, p-value < 0.001), though not very strong, between opportunities for practising EL outside of class and the belief that the Concept’s goals are attainable.

Furthermore, there is a moderate positive, significant correlation (r = 0.368, p-value < 0.001) between satisfaction with the current EL teaching curriculum and achieving ambitious language trilingual goals set by the Concept. It suggests that those teachers who are satisfied with the content of the EL curriculum might be more optimistic about reaching the target percentage of the trilingual population aimed at the Concept.

Also, we observed a moderate positive correlation (r = 0.383, p-value < 0.001) between EL teachers’ opinions on achieving the Concept’s goals and the current time allocation for EL instruction in schools. It suggests that EL teachers’ favourable views regarding the feasibility of creating a multilingual population under the Concept’s objectives coincide with the belief that the three hours allocated for EL instruction in schools are adequate.

As shown below, we employed ANOVA to determine if there are significant variances among groups relating to relevant variables.

3.3. Variations by Teaching Experience

We performed an ANOVA analysis to identify how teachers’ perceptions vary by experience, revealing some significant differences among teacher groups. It has been revealed that there are significant discrepancies in the opinions of at least two groups of EL teachers of different experience levels on the following:

- if school-based instruction is adequate to reach B2 level of language proficiency by grades 10–11(12);

- on the achievability of the ‘trilingual’ targets of the Concept;

- on the best grade to commence learning English.

No significant differences between EL teachers’ opinions were found based on the geographical location of the schools. Table 5 shows the descriptive statistics (sample size, mean and standard deviation) for key variables and subgroups explored in the ANOVA.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics (sample size (N), mean, standard deviation (SD)) for each subgroup within the ANOVA analysis.

3.3.1. Is English Instruction at School Alone Sufficient for a Student to Become Proficient at the B2 Level by Grades 10–11(12)?

The ANOVA analysis, conducted to analyse the perceptions of EL teachers relating to the adequacy of existing school-based instruction to reach the B2 level upon graduation, revealed interesting results. A significant F-value (F = 3.399) with a corresponding p-value of 0.005 (Table 6) indicates a statistically significant dissimilarity in opinion among teachers with different experience levels. The variation of viewpoints does not result from random chance: the low p-value signifies less than a 0.5% probability that such variation would occur by random chance. The post-hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated a significant variation in views between teachers in groups of 7–10 years of experience and groups of teachers of more than 20 years of experience concerning the question of EL instruction sufficiency for a student to be proficient at the B2 level upon the grades 10–11(12). The mean difference between these groups is about 0.32472, statistically significant with a p-value of 0.024 (Table 7). Accordingly, the results have shown that teachers with less experience (7–10 years) are more optimistic about the effectiveness of school-based teaching in reaching B2 level proficiency upon graduation, or might believe that the present-day curriculum and methods are enough to meet the needs of reaching B2 proficiency. On the other hand, teachers with solid experience in teaching (over 20 years) might be sceptical about relying only on school-based instruction to reach proficiency at the B2 level.

Table 6.

ANOVA analysis of variables by EL teachers’ years of experience.

Table 7.

Tukey HSD analysis of EL teachers’ groups based on different years of experience.

3.3.2. The Achievability of the ‘Trilingual’ Goals of the Concept

The ANOVA analysis displayed a significant difference (F = 5.454, p-value < 0.001) (Table 6) in the viewpoints of EL teachers based on their years of teaching. The statistical significance suggests that teachers’ perceptions of the achievability of the ‘trilingual’ targets outlined in the Concept are crucially influenced by years of experience. Teachers with more than 20 years of experience significantly differ in beliefs from teachers with under one year of experience, as displayed by a mean difference of −0.64952, resulting in a significant p-value of 0.002, as shown in the Tukey HSD test (Table 7). In other words, scepticism about reaching the English-speaking population proportion targets of the Concept under the current conditions among more skilled teachers with over 20 years of experience is in high contrast with the optimism among teachers having less than a year of experience.

3.3.3. Best Grade to Start Learning the EL

The ANOVA results’ F-value revealed a significant variance between different groups of teacher experiences regarding the right time to commence English instruction. With a strong F-value (4.342), the associated p-value was less than 0.001, which means that the variation in opinions was not the result of random chance (Table 6). Shifting to the Tukey HSD test, we detected key pairwise differences, specifically between teachers with less than a year of experience and those with solid experience (11–20 years). The mean difference is −0.98931, and the p-value of this comparison is 0.004, demonstrating a significant difference in opinions (Table 7). This means that teachers with 11–20 years of teaching expertise consider third grade the best time to start English instruction. However, teachers whose teaching experience is less than a year support the view that the first grade is more suitable to introduce EL.

3.4. Challenges Hindering Realisation of ELT

We employed Crosstab analysis to examine the interaction between categorical variables, such as geographical regions, and key factors affecting ELT, including internet quality, resource availability, and teacher shortages. This was performed because Crosstab analysis represents all these factors in detail in selected regions and allows one to locate significant patterns and discrepancies. It also allows us to visually depict frequency and response distribution to disclose regional inequalities and, presumably, their consequences for implementing ELT policies.

For example, Crosstab analysis revealed significant regional differences in the quality of the Internet that have varying impacts on the use of digital learning platforms. Furthermore, we have identified regions with severe shortages of EL teachers and those with better staffing. Finally, we have disclosed the uneven availability of educational resources, which could affect the quality of EL instruction.

3.4.1. Internet Quality

According to the official report (Statistical image of Kazakhstan education, 2019), all schools in the country are covered with an Internet connection. Regarding digital development, Kazakhstan is in the 50th place in the world (Zharkynbekova & Abaidilda, 2023).

However, despite being covered by the Internet, the speed of almost two thousand schools out of urban areas is below 4 Mbit/s (Nurbayev, 2021). The quality of the Internet, even in Astana, the country’s capital, does not satisfy the residents (Zhunishan, 2023). Also, there is a disparity between the Kazakhstani regions regarding Internet speed. For instance, regions such as Atyrau, Kostanay, North Kazakhstan, Turkestan, and West Kazakhstan experience serious challenges with Internet connection (Natsional’nyi sbornik Statistika sistemy obrazovaniia Respubliki Kazakhstan, 2020).

Still, as it is known, using online educational platforms to teach languages is of utmost importance as it enables teachers and students to acquire a foreign language effectively and more easily. Therefore, we included a relevant question in the survey to determine whether schools across Kazakhstan can effectively leverage online educational platforms related to ELT. The results of this analysis are as follows.

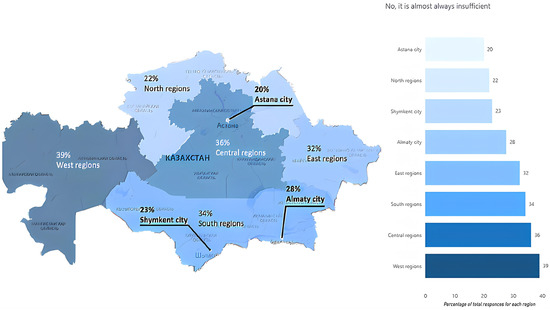

As depicted in Figure 4, in West Kazakhstan (including Aqtobe, Atyrau, and Mangystau cities), 39% of EL teachers stated that the Internet connection quality is ‘almost always insufficient’ to use online teaching platforms. In the central part of the country (Akmola, Karaganda, and Ulytau regions), 36% of respondents expressed similar concerns. In the southern part (comprising Kyzylorda, Turkestan, Zhambyl, Almaty region, and Zhetysu), 34% of respondents expressed the same concern. The eastern regions (Abay and East Kazakhstan) closely followed, with 32%. On the contrary, in Almaty and Shymkent cities, only 28% of EL teachers reported ‘No, it [Internet connection] is almost always insufficient’, suggesting somewhat better infrastructure compared to the mentioned regions. In North Kazakhstan (Kostanay, Pavlodar, and North Kazakhstan regions), 22% of the respondents experience Internet issues. That being said, Astana, the country’s capital, demonstrated the best rating among the surveyed regions, with only 20% of the respondents stating on the Internet connection quality that ‘No, it is almost always insufficient’.

Figure 4.

Internet connection quality in Kazakhstani public schools according to EL teachers.

3.4.2. EL Teachers’ Shortage

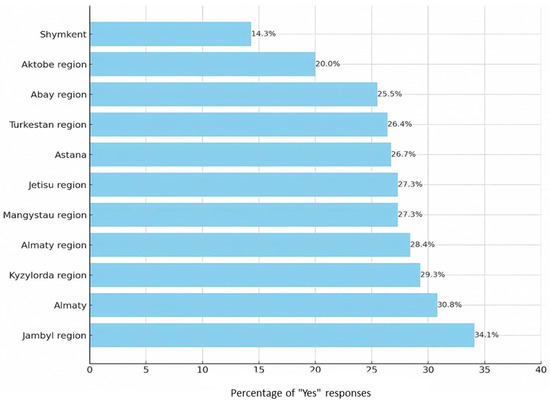

As part of our research, we asked participants whether their school faces a deficiency in EL teachers. Analysing the following data can provide insight into which regions are most affected by the deficiency of EL teachers based on the affirmative responses (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Percentage of schools facing a shortage of EL teachers by region.

The regions where approximately a third of respondents reported a shortage of EL teachers, as portrayed in Figure 5, are mostly located in the most populated Southern Kazakhstan. For instance, in the Jambyl region, 34.1% of respondents have admitted that their school needs more EL teachers. It is followed by Almaty city, Kyzylorda, and Almaty region with 30.8%, 29.3%, and 28.4%, respectively. That being said, Shymkent city (in the south) and Aktobe (in the northwest) have the best indicators: only a fifth or less of respondents reported a shortage of EL teachers.

3.4.3. Resources Availability

Furthermore, to identify whether schools across Kazakhstan are adequately equipped, we asked EL teachers to rank the availability of resources in the survey.

A total of 41.5% of the participants rated the resource provision in Almaty, the second major city, as ‘Good’. Meanwhile, 36.8% of EL teachers in the Almaty region expressed concerns about resource availability, rating it ‘Poor’. Such figures could indicate that neighbouring areas may significantly differ in resource availability.

The state of provisions in Astana city is better. Most EL teachers (52%) evaluated the resource accessibility from good to excellent (excellent: 8.0%, very Good: 13.3%, good: 30.7%). These responses may suggest a mixed but generally positive perception of resource availability. However, despite an optimistic view, some respondents from Astana (26.7%) ranked the provision as poor in meeting the needs of the students. There was a notable challenge in resource provision for EL teachers from the Kyzylorda region(in the south), where 51.2% ranked resources as ‘Poor’. This figure denotes the highest percentage among all regions, which may be evidence of a considerable resource shortage. Meanwhile, in Turkestan, more than half of the EL teachers (61.6%) consider resource provision satisfactory. For instance, figures indicate that 44.0% of the respondents ranked resource supply as ‘Good’, 6.6% as ‘Excellent’, and 11.4% as ‘Very Good’. These indicators may suggest that the school provision in this area is more available than in other regions mentioned above. The East Kazakhstan region displayed a particularly low number of responses (10), with 60% of EL teachers rating the resources’ availability as ‘Good’, and only four responses were received from the Kostanay region. Such few responses do not provide an exhaustive picture of the situation.

Considering the preceding, most respondents rate their resources as ‘Good’ across several regions. Nevertheless, there is a clear need for improvement in EL education resources in Kyzylorda and Almaty regions due to the significant percentages of ‘Poor’ ratings.

3.5. Analysis of EL Teachers’ Recommendations

The data from the survey can be regarded as a great source for revealing the EL teachers’ suggestions regarding improving practical, interactive, and technologically integrated approaches in language learning while acknowledging the value of cultural and creative components.

Among the answers related to the question ‘What recommendations do you have for enhancing the qualifications of English language teachers?’, the most popular recommendation was financial support for certifications in teaching English as a second or foreign language (e.g., TEFL, TESOL, CELTA, and DELTA), with 411 respondents endorsing it. This was followed by regular in-service training workshops on the latest teaching methodologies (320 votes) and language proficiency improvement courses (279 votes). Other significant preferences included collaboration with native English-speaking teachers for cultural and linguistic exchange (260 votes) and financial support for attending international conferences and seminars on language teaching (223 votes). Recommendations with less emphasis were on-the-job mentoring and coaching programmes (161 votes), access to online professional development resources (150 votes), and student feedback mechanisms to assess and improve teaching methods (125 votes). Thus, EL teachers suggest a strong focus on formal certifications, professional development, and proficiency improvement, complemented by cultural exchange and international exposure.

For the question ‘In your opinion, what can be done to improve English language teaching in Kazakhstan?’ the results showed that the most supported recommendation was to increase the duration of English lessons to at least 5 academic hours per week, endorsed by 372 respondents. This was closely followed by a call for increased teacher training (347 votes) and encouraging extra-curricular activities such as drama clubs, debates, speaking clubs, and reading clubs (308 votes). Other suggestions included increased investment in supportive materials (221 votes), enhanced language immersion opportunities for teachers and students (216 votes), and requiring English teachers to achieve at least an IELTS 8.0 proficiency level (215 votes). These recommendations highlight the importance of extended instructional time, professional development, and active learning opportunities outside the classroom, alongside resource investment and proficiency standards for teachers.

4. Discussion

This study offers a critical analysis of the current ELT policy in Kazakhstan. It presents a breadth of insights into the attitudes and challenges EL teachers encounter in a public school system. This paper integrates findings within the context of current research and its implications for the LPP. The analysis suggested a multivariant view of ELT in Kazakhstan, noting the ambitious nature of policy initiatives with implementation issues. Throughout our research, we have regularly encountered the dichotomy between top-down policy and the real situation in schools, applying the ‘bottom-up approach’ (Baldauf & Kaplan, 2005) framework. Applying this framework allowed us to ascertain the position of teachers in the policy implementation process, contrary to the traditional conception of them as passive actors obedient to the decree.

4.1. Views on the Effectiveness of ELT Policies

In answering the first research question, this study found that more experienced EL teachers tend to be sceptical about the effectiveness of ELT policies in achieving the ambitious goals of the ‘Concept for the Development of Language Policy for 2023–2029’. These findings align with Ricento and Hornberger’s (1996) ‘onion model’, which emphasises the complexities of policy implementation at multiple layers. As critical agents of policy enactment, teachers often encounter practical challenges that policymakers overlook. In this context, the scepticism of experienced teachers reflects their deeper understanding of these layers, particularly the limitations of macro-level planning to address classroom realities.

However, unlike Shohamy’s (2006) assumption that top-down policies tend to disempower teachers, leading to scepticism, our findings indicate that the less experienced teachers are still optimistic about policy achievability. This may be attributed to their recent exposure to more contemporary methodologies and less direct experience with the long-term effects of failures in policy implementation. Furthermore, responses from 233 teachers to the questionnaire indicated that delaying English instruction until grade 3 is preferable. The finding supports Stanlaw et al.’s (2018) concept that knowledge of the native language is more important for better assimilation. In addition, Cummins (2001) further emphasises the importance of the mother tongue, warning that children can quickly lose their ability to use it if it is not used in both educational and family settings. The decision by the Ministry of Education to delay English instruction reflects an understanding of this principle, aligning with teachers’ experiences that children benefit from a solid foundation in their first language before tackling a foreign one.

In addition, teachers’ responses from qualitative data (from some open-ended questions) support the idea that allocating two hours of EL per week would be sufficient to introduce young learners to the basics of English without detracting from other subjects. On the other hand, some teachers questioned the underlying need for teaching English at the primary level of education. As a teacher said, ‘I think there is no need to teach English in primary classes’ and ‘from fifth grade, it’s better to learn a foreign language’. These findings mirror broader debates in the field of language policy, where beliefs such as ‘younger is better’ and ‘longer exposure guarantees higher proficiency’ remain under dispute (Nunan, 2003; Singleton & Ryan, 2004). These perspectives caution against uncritical acceptance of early language instruction without thoroughly assessing its contextual implications, echoing some teachers’ concerns in this study.

Resource availability, albeit weak, positively correlates with teachers’ perceptions of policy achievability. The present findings may extend Breen’s (2002) insights into the crucial role of the educational environment in language learning success. Although Breen already accentuated the constraints imposed by resource limitations, our study has quantitatively illustrated the positive relationship between resource adequacy and teacher optimism about policy goals, especially within Kazakhstan’s multilingual policies. Moreover, a good resource level positively affects (moderately correlates) EL teachers’ satisfaction with the existing curriculum, perception of the sufficiency of EL teacher staff, and the school’s Internet quality. This illustrates that decision-makers on EL education policy should pay proper attention to the supply of the EL teaching process.

4.2. Variation of Perceptions by Teacher Experience Levels

In response to the second research question, the results of the ANOVA test disclosed a discrepancy in perceptions among EL teachers regarding the adequacy of school-based instruction that enables students to reach the B2 level of the language upon graduation from grades 10–11(12). It appears that teachers with 7–10 years of teaching expertise are more confident about the current school’s curriculum effectiveness in reaching the B2 level of proficiency. On the contrary, teachers with 20 years of experience exhibit scepticism, probably because of their broad years of experience where prior novelties in curricula did not meet their expectations. The dissimilarity in confidence levels between less and more experienced teachers can be understood through Ricento and Hornberger’s (1996) ‘onion model’, which illustrates the complexities of policy implementation across different layers. The scepticism of experienced teachers may indicate gaps in micro-level implementation, particularly the disconnect between top-down curriculum goals and the resources provided at the classroom level. This scepticism might be a sign that there is a need for additional measures (resources) or alternative teaching methodologies that will facilitate the achievement of the target proficiency level. Therefore, policymakers should integrate a bottom-up approach (Baldauf & Kaplan, 2005), leveraging the critical insights of experienced teachers to create more realistic and actionable policies.

The ANOVA analysis also highlights the significant influence of teaching experience on EL teachers’ perceptions regarding the achievability of the target level of proficiency in three languages (Kazakh, Russian, and English) of the Concept. This varied perception between less and more experienced teachers portrays a serious expectation gap, which may result from different levels of exposure to the continuing challenges and reality of language education. As stated earlier, the critical and realistic view of more experienced teachers in achieving the ‘trilingual’ goals may be shaped by their years of experience, which witnessed the outcomes of the past reforms. Conversely, the optimism of their less experienced colleagues could result from recent training or novelties in methodologies and the absence of disappointment from the past policy reforms. Here again, we must note that policymakers should consider strategies that integrate the ideas of experienced teachers and the enthusiasm of newer educators. This, in turn, encourages a more unified and realistic approach to achieving the aims of the policies of the ELT.

The outputs of the ANOVA and Tukey HSD tests and the teachers’ preferences from the Crosstab analysis indicate a decisive factor in the form of experience that influences the teacher’s view on introducing EL teaching into the schools’ curriculum. Based on statistical and empirical findings, we can estimate that EL teachers with more years of teaching experience may prioritise a child’s physical and mental development over learning a foreign language. On the contrary, their less experienced co-workers support taking advantage of young students’ flexibility.

4.3. Constraints Hindering the Realisation of ELT Policies

The answer to the third research question can be formulated as follows: The key challenges that hinder the realisation of the ELT policy in Kazakhstan include a significant digital divide, with disparities in Internet connectivity affecting the implementation of digital learning platforms, especially in rural areas. Additionally, there is a shortage of EL teachers in certain regions, particularly in southern Kazakhstan. Furthermore, the uneven distribution of educational resources exacerbates these challenges, with some regions, such as Kyzylorda and Almaty, facing resource shortages. These challenges highlight the need for more equitable resource allocation and infrastructure development to support ELT across the country.

Results obtained by Crosstab analysis demonstrated that disparities between regions and the poorer Internet connectivity in Western and Central Kazakhstan trigger the ‘digital divide’ problem, threatening equal access to high-quality education. These findings align with previous research (Zharkynbekova & Abaidilda, 2023), highlighting the unequal access to educational technology across Kazakhstan. Given this digital gap, infrastructure development and directed investments in this sphere are required, and every region should have the necessary resources for successful EL teaching. Especially now, when the world is increasingly shifting towards online and blended learning approaches.

An important aspect that should be mentioned is the shortage of EL teachers. It is particularly an issue in the Jambyl, Kyzylorda, and Almaty regions, which might create obstacles to implementing the comprehensive EL teaching policy. The problem of a lack of teachers influences the overall teaching process and should be resolved appropriately. Some possible solutions might be the development of training programmes, the provision of extra payments to teachers working in rural areas, and an overall increase in financing of EL teaching programmes to maintain an efficient and stable teaching staff.

Furthermore, there is a serious resource distribution issue. For example, the Kyzylorda and Almaty regions lacked sufficient equipment and resources. Identified resource disparity demonstrates the necessity of a more equitable distribution of educational materials for EL teaching to ensure all students have all resources for effective language learning. Equal resource allocation between regions may help improve the country’s ELT quality. This recommendation aligns with Spolsky’s model of language learning (Spolsky, 1998), proposing that the quality of language knowledge does not solely rely on teaching methods. Still, external factors such as the availability of educational resources, teacher training, and other opportunities have significant roles in the success or failure of language acquisition. Furthermore, in language policy studies, the importance of adequate resource levels is prioritised. For example, Hamid and Baldauf (2011) highlight that resource availability is critical to policy success, especially for under-resourced educational contexts like those in most post-Soviet states. This perspective underlines a need for Kazakhstan to address this issue to enhance ELT outcomes.

The implications of the present study go beyond the context of Kazakhstan, contributing meaningful insights into the challenges faced by ELT policy in multilingual and resource-lack societies worldwide. Key issues related to teachers’ lack of involvement in policy formulation, resource disparities, and the digital divide are not exclusively characteristic of Kazakhstan but resonate with other challenges reported in other contexts. For example, African countries facing multilingualism challenges often experience unequal resource allocation, negatively impacting their educational outcomes (Brock-Utne, 2015).

Furthermore, the digital divide in Kazakhstan is reflected in Southeast Asia, where unequal access to the Internet hinders integrating digital tools into ELT (Kirkpatrick & Liddicoat, 2019). These parallels underscore the need to adopt participatory, context-sensitive approaches like the ‘bottom-up approach’, which empowers teachers to become agents of change, aligning micro-level realities with macro-level goals. Situating the findings within this global context, this study addresses the challenges of ELT in Kazakhstan and provides a model for similar issues in other multilingual societies.

5. Conclusions and Limitations

This study calls for a more holistic and context-sensitive approach to ELT policy in Kazakhstan. Policymakers in Kazakhstan should not only pay attention to the macro-level goals of ELT policy but also ensure that resources, infrastructure, and support systems are created to facilitate the effective implementation of these policies. Integrating teachers’ insights and addressing their practical problems ultimately brings all stakeholders, including decision-makers, closer to attaining the ELT policy’s aims. Moreover, the findings of the study support the relevance of the bottom-up approach, demonstrating the need for grassroots involvement to address discussed gaps and empower teachers as agents of change. While the article is challenging top-down approach in LLP, it has shown that policies must consider contextual factors and frontline views. The results of this work also give useful lessons in other multilingual contexts by offering valuable insights into the complexities of implementing ELT policy in diverse and resource-constrained environments.

Prospective studies should be conducted in the long term to trace the effects of ELT policies, offering deeper insights into their sustainability and impact. A comparative approach could be useful in evaluating the ELT policies in similar socio-economic settings, determining shared challenges and successful interventions. Extended qualitative research, such as teacher interviews, would enhance our understanding of policy implementation nuances and teacher agency. The effectiveness of the teacher training programmes should also be examined to refine methods of supporting teachers in implementing the policy. These broader research engagements would extend the present study’s findings and provide a wide perspective on the challenges and successes of ELT policy implementation in Kazakhstan and similar contexts.

The limitations of this research include the fact that it is based on self-reported data from EL teachers, which may have biased results due to subjective perceptions. Besides, the study targeted public schools, which might not give a full view of what EL teachers undergo in other educational settings, such as private schools.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.I., A.A. and A.Z.; methodology, D.I., A.A. and A.Z.; software, D.I.; validation, D.I., A.A. and A.Z.; formal analysis, D.I., A.A. and A.Z.; investigation, D.I., A.A. and A.Z.; resources, D.I., A.A. and A.Z.; data curation, D.I., A.A. and A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, D.I., A.A. and A.Z.; writing—review and editing, D.I., A.A. and A.Z.; visualization, D.I., A.A. and A.Z.; supervision, A.A. and A.Z.; project administration, A.A. and A.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Science Department of the L.N. Gumilyev Eurasian National University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data collected by the authors is available via link: https://figshare.com/s/cb40ff3f3cbc8a2af8ed (accessed on 13 November 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Questionnaire

- Your gender *

- Male

- Female

- How old are you? *

- 18–24

- 25–34

- 35–54

- 55–63

- Where is your school? *

- Astana

- Almaty

- Shymkent

- Abay region

- Akmola region

- Aktobe region

- Almaty region

- Atyrau region

- East Kazakhstan region

- Jambyl region

- Jetisu region

- Karaganda region

- Kostanay region

- Kyzylorda region

- Mangystau region

- North Kazakhstan region

- Turkestan region

- Ulytau region

- Pavlodar region

- West Kazakhstan region

- How many years of experience do you have in English language teaching? *

- Less than a year 1–3 years

- 4–6 years

- 7–10 years

- 11–20 years

- More than 20 years

- In what school level do you teach English? (You can choose more than one) * (multiple choice)

- Primary school (1–4 grades)

- Junior school (5–9 grades)

- Secondary (9–11 (12) grades)

- Is starting to learn English language in the third grade, when a student is 8 or 9 years old, the right time? *

- It’s perfect time when a child fully acquires mother tongue

- Students should start learning English earlier than third grade

- No, it is more appropriate learning English later than third grade

- The timing should be based on the curriculum and resources available

- There is no single “right” time to start learning English; it varies by cultural and educational context

- I am not sure, no opinion

- Primary school students are taught only 2 h a week English language, is this time enough to acquire language at an adequate level? *

- Enough

- Probably enough

- Unsure

- Probably not enough

- Not enough

- Secondary school students are taught only 3 h a week English language, is this time enough to acquire language at an adequate level? *

- Enough

- Probably enough

- Unsure

- Probably not enough

- Not enough

- Are you familiar with the governmental Concept for the development of language policy in the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2023–2029? *

- Very familiar

- Somewhat familiar

- Aware but not informed about the details

- Not very familiar

- I am not familiar at all

- How effective do you think the “Trilingual Education” Program initiated in 2017 is? Does it have a positive influence on the overall language proficiency development of your students? *

- Very effective

- Somewhat effective

- Neither effective nor ineffective

- Somewhat ineffective

- Very ineffective Extremely effective

- According to the concept of language policy for years 2023–2029, it has a concrete target to reach the Proportion of the population speaking three languages—Kazakh, Russian and English in 2024—15.5%, 2025—16%, 2026—16.5%, 2027—17%, 2028—17.5%, 2029—18%. In this regard, do you think these plans are reachable with the current learning and teaching hours of the English language at school (3 h a week for secondary classes, and 2 h a week in primary)? *

- Fully reachable

- Somewhat reachable

- Minimally reachable

- Not reachable at all

- Are you satisfied with the official curriculum content of the English language at school? *

- Satisfied

- Very satisfied

- Somewhat satisfied

- Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied

- I think curriculum needs some improvements

- I have not enough teaching experience to assess the content of the curriculum

- Do you agree that teaching English at school alone is sufficient for a student to become proficient at the B2 level by grades 10–11(12) in the English language? *

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Disagree

- Strongly disagree

- On average how many students are in your classes? *

- 10–15

- 16–20

- 21–30

- More than 30

- Are the classes of English lessons divided into groups according to the student’s level of English language? *

- Yes, always

- Most of the time

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- No, never

- How would you rate the availability of resources (books, workbooks, multimedia materials (video and audio resources), authentic materials etc.) for English language education in your school? *

- Poor

- Average

- Fair

- Good

- Very good

- Excellent

- Do you have a language lab at school? *

- Yes, and it is in use

- Yes, but it is not in use

- No

- Is your school’s internet connection sufficient to effectively use online teaching platforms? *

- Yes, it is always sufficient

- Mostly sufficient, but there are occasional issues

- It is sufficient during off-peak hours only

- No, it is almost always insufficient

- I don’t use online teaching platforms enough to evaluate

- Not applicable—I do not use teaching platforms

- Does your school currently face a shortage of English language teachers? *

- Yes

- No

- I do not know

- To what extent do you agree that teachers at schools spend a significant amount of time on bureaucratic tasks, potentially detracting from their teaching responsibilities? *

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neutral

- Disagree

- Strongly disagree

- What do you believe is most lacking in effective teaching/learning of English language? (You can choose more than one) * (multiple choice)

- Quality textbooks

- Language lab

- Target language environment (speaking, reading clubs to practice)

- Training for teachers

- Foreign exchange programs for teachers

- Foreign exchange programs for students

- More class hours

- Better English language policy of the Government

- Other

- Are your students able to practice English at school (speaking clubs, reading clubs for example) outside of the English language classes? *

- Frequently

- Occasionally

- Rarely

- Very rarely

- Never

- What challenges have you faced in implementing any government-directed changes to the English language curriculum? (You can choose more than one option) * (multiple choice)

- Lack of resources

- Limited professional training

- Conflicting methodologies

- Time constraints

- Ambiguity in guidelines

- Lack of standardization

- Overloaded curriculum

- Bureaucracy

- Other

- Are the qualification programs you attend self-funded or state-funded? *

- I fully self-fund the qualification programs

- The qualification programs are fully state-funded

- There is a mix of self-funding and state funding for the programs

- The qualification programs are funded through scholarships or grants

- In your view, from what grade is it better to study English? *

- Kindergarten

- First grade

- Second grade

- Third grade

- Fourth grade

- Fifth grade

- In your opinion, what is the optimal number of academic hours for teaching English language in Primary school? *

- six hours a week

- five hours a week

- four hours a week

- three hours a week

- Other

- In your opinion, what is the optimal number of academic hours for teaching English language in Secondary school? *

- three hours a week

- four hours a week

- five hours a week

- six hours a week

- Other

- In your opinion, what can be done to improve English language teaching in Kazakhstan? (You can choose more than one option) * (multiple choice)

- English teachers should have at least IELTS 8.0

- English lessons should be at least 5 academic hours a week

- Increased teacher training

- Enhanced language immersion opportunities for teachers and students as well

- Increased investment in supportive materials

- Encourage extra-curricular activities (drama clubs, debates, speaking clubs, reading clubs)

- Other

- What recommendations do you have for enhancing the qualifications of English language teachers? (You can choose more than one option) * (multiple choice)

- Regular in-service training workshops on the latest teaching methodologies

- Financial support for Certifications in teaching English as a second or foreign language (e.g., TEFL, TESOL, CELTA, DELTA).

- On-the-job mentoring and coaching programs

- Language proficiency improvement courses (e.g., advanced grammar, pronunciation).

- Financial support and enhanced opportunity to attend international conferences and seminars on language teaching

- Access to online professional development courses and resources

- Collaboration with native English-speaking teachers for cultural and linguistic exchange

- Student feedback mechanisms to continually assess and improve teaching methods

- Other

- What recommendations would you add to the curriculum of the English language? (You can choose more than one option) * (multiple choice)

- Enhanced focus on practical communication skills, such as speaking and listening

- Greater emphasis on creative writing to develop expressive abilities

- Integration of technology and digital media to support language learning

- Cultural studies component to improve understanding of English-speaking countries

- Language immersion experiences, such as conversation clubs or study abroad programs

- Introduction to variations of English (American English, British, Australian) for comparative

- linguistic studies

- Other

References

- 2022–2023 oqu jılında Qazaqstan Respublïkasınıñ orta bilim beru uyımdarındağı oqu-tärbïe procesiniñ erekşelikteri turalı. Nusqawlıq-ädistemelik xat. (2022). I. Altynsarin NAO. Available online: https://uba.edu.kz/storage/app/media/IMP/2022-2023-ou-zhylynda-azastan-respublikasyny-orta-bilim-beru-yymdarynda-ou-trbie-protsesin-yymdastyrudy-erekshelikteri-turaly-distemelik-nsau-khat-1-23122022.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- Ahn, E., & Smagulova, J. (2022). English language choices in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. World Englishes, 1(44), 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akynova, D. (2014). Kazakhsko-Angliyskiye yazykovyye kontakty:kodovoye pereklyucheniye v rechi kazakhov-bilingvov. L.N. Gumilyov ENU. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, P. (2005). Knowledge management for e-learning. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 42(2), 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldauf, R. B. (2006). Rearticulating the case for micro language planning in a language ecology context. Current Issues in Language Planning, 7(2–3), 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldauf, R. B., & Kaplan, R. B. (2005). Language planning and policy in Europe: Hungary, Finland and Sweden. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Baldauf, R. B., & Liddicoat, A. (2008). Language planning and policy: Language planning in local contexts. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokayev, B., Torebekova, Z., & Davletbayeva, Z. (2020). Implementation of information and communication technology in educational system of Kazakhstan: Challenges and opportunities. Public Administration and Civil Service, 4, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, M. (2002). From a Language policy to classroom practice: The Intervention to identity and relationships. Language and Education, 16(4), 260–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock-Utne. (2015). Multilingualism in Africa: Marginalisation and empowerment. In Multilingualism and development (pp. 61–79). British Council. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, C., & Baldauf, R. B. (2011). Micro Language Planning. In Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning: Volume 2. Routledge, Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Concept for the Development of Higher Education and Science in the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2023–2029. (2023). Available online: https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/P2300000248 (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Cummins, J. (2001). Bilingual children’s mother tongue: Why is it important for education? Sprogforum, 7(19), 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- EF EPI. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.ef.com/wwen/epi/ (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Fenton-Smith, B., & Gurney, L. (2016). Actors and agency in academic language policy and planning. Current Issues in Language Planning, 17(1), 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierman, W. (2006). Language and education in post-soviet Kazakhstan: Kazakh-medium instruction in urban schools. The Russian Review (Stanford), 65(1), 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. (1986). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration (Vol. 349). University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hajar, A., Babeshko, Y., & Smagulova, J. (2023). EMI in Central Asia. In C. Griffiths (Ed.), The practice of english as a medium of instruction (EMI) around the world (pp. 93–111). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, M. O., & Baldauf, R. B. (2011). English and socio-economic disadvantage: Learner voices from rural Bangladesh. Language Learning Journal, 39(2), 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornberger, N. H., & Johnson, D. C. (2007). Slicing the onion ethnographically: Layers and spaces in multilingual language education policy and practice. TESOL Quarterly, 41(3), 509–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D. C. (2013). Language policy. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kachru, Y., & Smith, L. (2008). Cultures, contexts, and world englishes. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kambatyrova, A., Assylbekova, B., & Goodman, B. (2022). Primary School English Language Education in Kazakhstan. In S. Zein, & Y. Butler (Eds.), English for Young Learners in Asia (1st ed., pp. 48–64). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, A., & Liddicoat, A. (Eds.). (2019). The routledge international handbook of language education policy in Asia. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kunanbayeva, S. (2004). Concept of language education in the Republic of Kazakhstan (in Russian). KazUMO and MYA after Abylai Khan. [Google Scholar]

- Manan, S. A., Channa, L. A., David, M. K., & Amin, M. (2021). Negotiating English-only gatekeepers: Teachers’ agency through a public sphere lens. Current Issues in Language Planning, 22(3), 290–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manan, S. A., & Hajar, A. (2024). Understanding English medium instruction (EMI) policy from the perspectives of STEM content teachers in Kazakhstan. TESOL Journal, 2(847), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manan, S. A., Mukhamediyeva, S., Kairatova, S., Tajik, M. A., & Hajar, A. (2023). Policy from below: STEM teachers’ response to EMI policy and policy-making in the mainstream schools in Kazakhstan. Current Issues in Language Planning, 25(1), 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P. (1999). Close encounters of a bilingual kind: Interactional practices in the primary classroom in Brunei. International Journal of Development, 19(2), 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menken, K., & García, O. (2010). Stirring the onion: Educators and the dynamics of language education policies (looking ahead). In Negotiating language policies in schools: Educators as policymaker (pp. 249–261). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty, A., Panda, M., & Pal, R. (2010). Language policy in education and classroom practices in India. In Negotiating language policies in schools. educators as policy makers (pp. 212–231). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Natsional’nyi sbornik Statistika sistemy obrazovaniia Respubliki Kazakhstan (p. 312). (2020). JSC National research center and assessments of education ‘Taldau’ named after Akhmet Baitursynuly. Available online: https://taldau.edu.kz/publikaciya/nacionalnyj-sbornik-statistika-sistemy-obrazovaniya-respubliki-kazahstan-2022-g (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Nunan, D. (2003). The impact of english as a global language on educational policies and practices in the Asia-Pacific region. TESOL Quarterly, 37(4), 589–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurbayev, Z. (2021). Inequality between students of rural and urban schools in Kazakhstan: Causes and ways to address it. Central Asia Program. Available online: https://www.centralasiaprogram.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/cap-paper-no.-268-zhaslan-nurbayev.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- OECD & The World Bank. (2015). OECD reviews of school resources: Kazakhstan 2015. OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheim, A. N. (2005). Questionnaire design, interviewing and attitude measurement (New ed., reprinted). Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Ricento, T. (Ed.). (2006). An introduction to language policy: Theory and method. Blackwell Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Ricento, T., & Hornberger, N. (1996). Unpeeling the Onion: Language Planning and Policy and the ELT Professional. TESOL Quarterly, 30(3), 401–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, G. (2020). Teacher agency. In M. A. Peters (Ed.), Encyclopedia of teacher education (pp. 1–5). Springer Singapore. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shohamy, E. (2006). Language policy: Hidden agendas and new approaches (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, D., & Ryan, L. (2004). Language acquisition: The age factor. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Smagulova, J. (2008). Language policies of kazakhization and their influence on language attitudes and use. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 3–4, 440–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolsky, B. (1998). Conditions for second language learning: Introduction to a general theory. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stanlaw, J., Adachi, N., & Salzmann, Z. (2018). Language, culture, and society: An introduction to linguistic anthropology (7th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Statistical image of Kazakhstan education. (2019). NEBD. Available online: http://iac.kz/en/project/nobd (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- Tajik, M. A., Namyssova, G., Shamatov, D., Manan, S. A., Zhunussova, G., & Antwi, S. K. (2023). Navigating the potentials and barriers to emi in the post-soviet region: Insights from kazakhstani university students and instructors. International Journal of Multilingualism, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Leech, K., & Liddicoat, A. (2014). Macro-language planning for multilingual education: Focus on programmes and provision. Current Issues in Language Planning, 15(4), 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdiviezo, L. (2010). Angles make things difficult. In Negotiating language policies in schools: Educators as policymakers (pp. 72–87). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Varpanen, J., Laherto, A., Hilppö, J., & Ukkonen-Mikkola, T. (2022). Teacher Agency and Futures Thinking. Education Sciences, 12(3), 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongalis-Macrow, A. (2007). I, Teacher: Re-territorialization of teachers’ multi-faceted agency in globalized education. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 28(4), 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V-Shkolakh-Kazakhstana-Anglijskij-Yazyk-Nachnut-Izuchat-S-Tretego-Klassa-. (2022, June). Kt.Kz. (2022). Available online: https://www.kt.kz/rus/education/v_shkolah_kazahstana_angliyskiy_yazyk_nachnut_izuchat_s_1377934744.html (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Yakavets, N., Winter, L., Malone, K., Zhontayeva, Z., & Khamidulina, Z. (2023). Educational reform and teachers’ agency in reconstructing pedagogical practices in Kazakhstan. Journal of Educational Change, 24(4), 727–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]