1. Introduction

Understanding and promoting positive attitudes toward disability are essential for effective healthcare and inclusive educational practices (

Shields et al., 2024). Currently, knowledge about disability within society is limited, and it is even scarcer among professionals who work with people with disabilities. This lack of education and information may be strongly associated with negative attitudes and stigmatizing beliefs (

Arias González et al., 2016;

Scior & Werner, 2015). The original definition of attitude encompassed cognitive, affective, motivational, and behavioral components, describing it as “a mental and neural state of readiness, organized through experience, exerting a directive and dynamic influence upon the individual’s response to all objects and situations with which it is related” (

Allport, 1935). Promoting activities that allow participants to experience and learn about disability is identified as a crucial method to enhance attitudes toward individuals with disabilities in educational settings (

Ocete Calvo et al., 2015;

Reina et al., 2016). Particularly, university programs in physical activity and sports science (PASS), occupational therapy (OT), and early childhood education (ECE) can integrate these activities into their curricula to prepare future professionals. The attitudes toward disability among different professionals significantly influence their practice and the quality of their care for individuals with disabilities. Positive attitudes are essential for promoting inclusive environments, reducing stigmatization, and enhancing the overall well-being of individuals with disabilities (

Babik & Gardner, 2021).

The scientific community has extensively examined teachers’ attitudes toward disability, analyzing the various components influencing these attitudes across different contexts and educational levels, and uncovering significant differences (

Domingo Martos et al., 2019;

Garc, 2017;

Monjas et al., 2014). Some researchers claim that more highly trained teachers in the field of diversity attention measures are dissatisfied with the current rigid academic curriculum in Spain for developing inclusive methodologies (

Domingo Martos et al., 2019). As demonstrated in recent international literature reviews (

Quispe-Choque et al., 2023), in early childhood education, teachers typically demonstrate more positive attitudes toward inclusion, while in primary education, these attitudes remain generally favorable, although teachers encounter greater challenges due to having to meet advanced curriculum requirements; furthermore, in secondary education, attitudes toward inclusion may become more cautious or hesitant, as educators face significant difficulties in adapting content and teaching methods to accommodate a more diverse student body with increasingly complex needs.

Education is considered one of the primary drivers for promoting positive attitudes toward disability. Therefore, the attitudes toward disability among Spanish university students have been previously studied and analysed. Students of the social sciences, law, or health sciences exhibited more positive attitudes toward disability compared to those of architecture and engineering (

Garabal-Barbeira et al., 2018;

Polo Sánchez et al., 2011,

2018). Among these, some authors highlight how those with primary education, ECE, pedagogy, and social education degrees showed more positive attitudes (

Polo Sánchez et al., 2018). University students’ attitudes toward disability are crucial as they are future professionals who will drive societal transformation (

Moreno Pilo et al., 2022;

Moriña, 2017). However, using the same questionnaire as employed in this research, it has been demonstrated at a Spanish-speaking university that during this educational stage, there is a lack of intense curricular experiences that develop skills and attitudes in favor of diversity (

Atoche-Silva et al., 2021).

Nevertheless, attitudes toward disability among health professionals and students, such as occupational therapists, and how these attitudes influence their practices, have been less studied. In recent years, adopting positive attitudes toward disability has become a critical goal in healthcare education (

Shields et al., 2024). As future health professionals, students must develop empathy, understanding, and inclusivity when interacting with individuals with disabilities, and practical experiences and interactions with people with disability can shape more empathetic and inclusive perspectives among future healthcare providers (

Friedman & VanPuymbrouck, 2021;

VanPuymbrouck & Friedman, 2020). University studies play a pivotal role in shaping how future practitioners perceive and interact with individuals with disabilities.

In the field of healthcare and education, fostering positive attitudes toward disability is a critical endeavor. In this way, each discipline under study—PASS, OT, and ECE—interacts with disability and healthcare in unique ways. Furthermore, understanding attitudes toward disability has important implications for the success of inclusive policies. PASS programs focus on physical health and activity, often emphasizing the physical capabilities and performance of individuals with disabilities; furthermore, they are closely related to physical education, which is one of the crucial subjects for developing positive attitudes toward disability (

Kohl et al., 2013). In this way, physical education teachers’ perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes significantly influence the success of inclusive education initiatives, as they directly affect the adaptation of methodologies and the integration of students with disabilities into classroom activities (

Gámez-Calvo et al., 2024). Intervention programs in physical education lessons, such as those involving direct contact with individuals with disabilities, theoretical and practical training, or the use of adaptive sports, have shown varying levels of success in shifting attitudes toward inclusivity (

Abellán Hernández & Hernández Martínez, 2016;

Reina et al., 2020). However, studies reveal significant gaps, such as the limited scope of teacher training programs and the lack of consistent methodologies, which impede the widespread adoption of inclusive practices (

Hodge et al., 2017). On the other hand, OT directly addresses the functional abilities of individuals with disabilities, aiming to enhance their participation in daily activities (

American Occupational Therapy Association, 2020), Occupational therapists’ attitudes toward disability profoundly impact the effectiveness of their interventions and client outcomes, considering not just physical impairments but also individual abilities, interests, and environmental contexts (

Friedman & VanPuymbrouck, 2021). Nowadays, research examining both the explicit and implicit attitudes of OT students throughout their graduate programs reveals insights into how formal education can impact perceptions and biases associated with disability (

Friedman & VanPuymbrouck, 2021). ECE involves fostering developmental milestones and supporting children with varying needs, including those with disabilities (

Hernández-Beltrán et al., 2023). Also, teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education determine students’ learning opportunities and increase their sense of belonging and participation (

Sevilla et al., 2018). The inclusive education model is defined as an instructional approach that advocates for equal opportunities for all students, especially those with disabilities or specific needs (

Erkilic & Durak, 2013). Inclusive education involves processes aimed at removing or minimizing barriers that hinder students’ active participation and learning, incorporating cultural, social, practical, and political dimensions (

Booth & Ainscow, 2018). It aims to provide quality education for all students, with particular consideration of those in vulnerable situations. Moreover, it underscores the importance of recognizing that each student requires individualized attention due to varying capacities, learning speeds, and needs (

Martínez Martín & Bilbao León, 2013).

This study investigates the influence of career selection and academic progression on university students’ attitudes toward disability and the subsequent effects on their professional practices. By examining these factors, the aim of this study is to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the differences in attitudes toward disability among university students from various education- and health-related programs within their chosen fields. Through this exploration, we aim to identify potential areas for improvement in educational curricula and training programs to better prepare future professionals for inclusive educative and healthcare practices in diverse settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Considerations

This study employs a cross-sectional comparative design to investigate the influence of career selection and academic progression on university students’ attitudes toward disability and the associated impact on professional healthcare and educative practices. All the data were collected anonymously. Prior to the commencement of the training programs, participants were informed about the details of the research, including its potential risks and benefits, and they provided informed consent. This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki (

Gray et al., 1978) and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Extremadura (registration code: 151/2022).

2.2. Participants

A total of 446 university students from Extremadura, studying across PASS, OT, and ECE, participated in this comparative study. The selection of the PASS, OT, and ECE degrees was based on their close connection to the topic of attitudes toward people with disabilities. PASS students are trained in areas related to inclusion through adapted physical activity and inclusive sports. Furthermore, their curriculum often integrates elements of education and health, such as adaptive physical activity, sports pedagogy, and health promotion, creating a unique intersection between these two fields. Meanwhile, ECE students represent a key profile in shaping inclusive attitudes from the earliest stages of education, and OT students contribute a perspective focused on rehabilitation and supporting the autonomy of people with disabilities. The eligibility criteria included all suitably aged participants who were involved in university programs related to PASS, OT, and ECE at the University of Extremadura, who provided signed informed consent to the research team. Data were collected over two consecutive academic years (2022/2023 and 2023/2024).

Participants included both first-year and final-year students from each program, allowing for a comparative analysis of attitudes toward disability at different stages of their academic progression. The sample’s (

n = 446) mean age was 21.20 years (SD = 3.171), and the sociodemographic characteristics and the characteristics related to contact with people with disabilities are shown in

Table 1.

2.3. Procedure

The sample was obtained through a cluster sampling method, selecting natural groups of students who regularly attended classes for the selected university degrees. The fieldwork and data collection were planned based on four key documents: the informed consent form, the scale itself, the list of students to be interviewed, and the guidelines for the interviewers. The instructor who collaborated in the data collection was contacted via email, in which the purpose of this study was explained. The interviewers responsible for data collection were experienced researchers who were specifically trained for this study. The students signed the informed consent form and proceeded to complete the questionnaire using Google Forms in person in the classroom itself and during class hours, where any questions were addressed to ensure the items were fully understood by the participants.

2.4. Variables and Instruments

To analyze the attitudes toward disability among the different university students, and the relationships with their future healthcare and educative practices, several variables have been selected.

Sociodemographic variables (i.e., gender or age), variables related to contact with people with disabilities (i.e., prior contact with people with disability or reason for contact) (

Table 1), and the assessment of attitudes toward disability: score on the Attitudes Toward People with Disabilities Scale (

Arias González et al., 2016).

The Attitudes Toward People with Disabilities Scale (

Arias González et al., 2016) was used to assess the attitudes toward disability among the different university students. This questionnaire has been scored and adapted using a sample of 976 professionals from various fields—primarily healthcare and education, which accounted for 70% of the sample due to their significant role in working with people with disabilities— and demonstrates ideal characteristics for this research. This scale is used to assess attitudes toward disability, being one of the most scientifically accepted and widely used scales worldwide due to its high validity and reliability. In

Table 2, the comparison of the Cronbach’s alpha between the original questionnaire and the data collected is show. According to established guidelines, a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient above 0.7 is considered indicative of good reliability (

Taber, 2018). Therefore, the collected data are deemed reliable and representative of attitudes toward disability among the sample participants. The Cronbach’s alpha below 0.7 for Factor 3 (IP) suggests lower internal consistency in participants’ responses regarding this type of intervention and its economic profitability.

This tool is a Likert-type questionnaire, consisting of a summative rating scale with four levels of agreement. It comprises 31 items, grouped into 3 factors: Factor 1, “Social and Interpersonal Relationships with People with Disabilities”, includes 13 items related to feelings, behavioral intentions, and thoughts of individuals when they need to engage in a personal or social interaction with a person with a disability. Factor 2, “Normalized Life”, consists of 13 items that refer both to the rights to lead a normalized life and to equal opportunities, as well as to the possibility or ability of people with disabilities to manage different areas of life like people without disabilities. Factor 3. “Intervention Programs”. refers to specific actions aimed at promoting the integration and full inclusion of people with disabilities, as well as judgments about the economic profitability of these actions.

In addition to conducting a descriptive analysis, this study involved a detailed examination of the educational and curricular plans across the mentioned degree programs (

Table 3). This analysis aimed to assess the potential influence of academic training on attitudes toward disability, so all the competences mentioning “disability”, “diversity” or “inclusion” were included. By comparing these elements across disciplines, we sought to determine whether exposure to these topics within academic settings might correlate with more inclusive attitudes among university students. This approach allowed for a comprehensive understanding of how formal education might shape perceptions and attitudes toward individuals with disabilities.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The data analysis was performed using the statistical package SPSS 24.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0, Chicago, IL, USA). Initially, exploratory analysis by the researchers ensured the data quality. Additionally, an analysis was conducted, and the normality of the variables was assessed. Subsequently, a descriptive analysis of the various variables (mean values and standard deviations) was conducted. To analyze the relationships between variables, a correlational analysis was carried out.

3. Results

To examine the potential variations in outcomes across different demographic and educational factors, a series of statistical analyses were conducted. Understanding group differences is essential for identifying patterns that may inform targeted interventions, policy adjustments, or further research into specific characteristics associated with academic performance and progression. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to assess the differences between groups based on various categorical factors. First, the significant differences based on the degree and academic year were analyzed. The ANOVA revealed statistically significant differences across the groups (

p < 0.05) (

Table 4).

Following the detection of these significant differences, a post hoc multiple comparison test using the Games–Howell method was performed, because in most of the factors studied, the assumption of homoscedasticity, or equality of variances between groups, was not met. This subsequent analysis identified the specific group pairs between which significant differences existed, providing a clearer understanding of the distinct variations among the groups. The results showed significant differences in several evaluated factors.

Considering the different factors depending on the degree, for Factor 1, significant differences were observed between fourth-year PASS and fourth-year OT students (−2.735, p = 0.001), and between fourth-year PASS and fourth-year ECE students (−1.519, p = 0.043). For Factor 2, significant differences were only found between fourth-year PASS and fourth-year OT students (−2.741, p = 0.000), and between fourth-year ECE and fourth-year OT students (−1.472, p = 0.030). For Factor 3, significant differences were noted between first-year PASS students and first-year OT students (−1.251, p = 0.028), between fourth-year PASS and fourth-year OT students (−0.950, p = 0.037), between fourth-year ECE and OT students (−0.953, p = 0.027) and between first-year ECE students and first-year OT students (−1.694, p = 0.006). Finally, in terms of the Total Score, significant differences were identified between fourth-year PASS students and fourth-year OT students (−6.425, p = 0.000), and between fourth-year ECE and fourth-year OT students (−3.640, p = 0.017).

Regarding the different factors depending on the different academic years of the same degree, for Factor 1, significant differences were observed between first- and fourth-year ECE students (−3.874, p = 0.016), and between first- and fourth-year OT students (−3.210, p = 0.009). For Factor 2, significant differences were found only between first- and fourth-year OT students (−2.332, p = 0.017). For Factor 3, significant differences were noted between first-year and fourth-year PASS students (−1.076, p = 0.031), and between first-year and fourth-year ECE students (−1.515, p = 0.007). Finally, in terms of the Total Score, first-year ECE students showed significant differences compared to fourth-year ECE students (−7.047, p = 0.023), and significant difference were noted between first- and fourth-year OT students (−6.316, p = 0.005).

Role of the Degree Program in the Association Found: Classification Tree

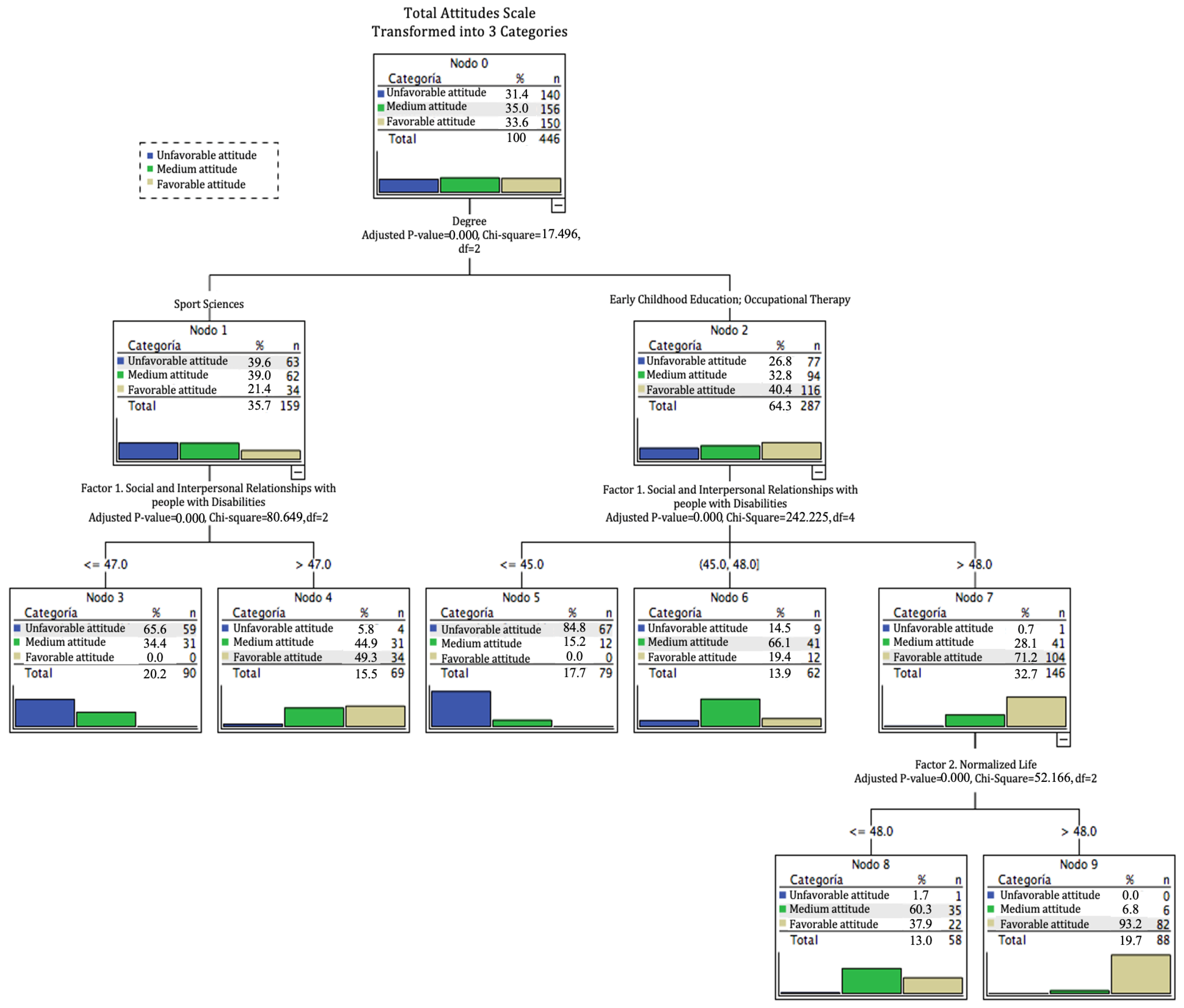

For analyzing the role of the degree program in the associations found, a classification tree was created. In the classification tree (

Figure 1), the dependent variable was the total score on the Attitudes Toward People with Disabilities Scale, grouped into three categories of more favorable or less favorable attitudes toward disability categorized into three groups based on predefined score ranges of the initial scale (0–108 category 1 “less favorable”; 109–115 category 2 “average score”; 116–124 category 3 “high score”), the independent variables were the degree program, and the different factors of the questionnaire. In

Figure 1, it can be observed that the degree program is significantly associated with a better score on the Attitudes Toward People with Disabilities Scale. In this way, the decision tree groups the students into two groups: on the one side, the students of PASS (Node 1), and on the other side, the students of ECE and OT (Node 2). It groups the students in Group 2 for behaving similarly in terms of the questionnaire scores. While most OT and ECE students (40.4%) score very high on the scale, the scores among the PASS students are more variable: less favorable score (39.6%), average score (39.0%), and high score (21.4%). Thus, the factor that determines a better score on the total scale is the “Social and Interpersonal Relationships” factor, with those scoring >47 showing better scores on the total questionnaire, Node 4, Node 6 and Node 7. As shown in Node 7, 71.2% of the ECE and OT students who score >48 for the social and interpersonal relationships factor show very favorable attitudes toward disability on the total scale. On the other hand, as shown in Node 4, only 49.3% of the PASS students who score >47 for the social and interpersonal relationships factor show very favorable attitudes toward disability on the total scale.

4. Discussion

The objective of this study is to comprehensively examine the differences in attitudes toward disability among university students enrolled in various educational and health related academic programs. This investigation seeks to highlight potential gaps in educational curricula and training, aiming to enhance the preparation of future professionals for inclusive practices in both educational and healthcare contexts. This study provides a comparative analysis of attitudes toward disability among university students studying for ECE, OT and PASS degrees at the University of Extremadura. As in earlier studies (

Felipe Rello et al., 2018;

López & Moreno, 2019;

Martínez Martín & Bilbao León, 2013), this work uses a survey to analyze university students’ attitudes toward disability. Through the Attitudes Toward People with Disabilities Scale (

Arias González et al., 2016), the attitudes toward disability were measured. Moreover, the internal consistency (

Taber, 2018) of the total score was found to be high, demonstrating robust reliability across the measured constructs. However, the third factor, IP, exhibited low reliability, as well as the original questionnaire, which might initially suggest a potential weakness in the measurement model.

Previous studies indicate that among the factors influencing attitudes toward disability in university students are gender (

Moreno Pilo et al., 2022), and their vocational choice, which is reflected in the degree program pursued. In terms of the variables related to the university degree and academic year, significant differences were found in all the variables analysed. The data indicate that the degree program is significantly associated with improved scores on the Attitudes Toward People with Disabilities Scale. The significant differences in Factor 1, “Social and Interpersonal Relationships with People with Disabilities”, can be attributed to varying emphases in academic curricula. OT and ECE degree programs prioritize attention toward diversity and disability throughout their training, leading to more frequent and meaningful interactions with individuals with disabilities. In contrast, sports science students encounter these topics only in their final year during formative practices, with limited contact. For Factor 2, “Normalized Life”, the differences may be due to the specificity of the training programs, which include aspects related to the normalization of people with disabilities. In relation to Factor 3, “Intervention Programs”, the observed differences may result from students seeing and appreciating the importance of intervention programs in various areas for people with disabilities throughout their university training. Some researchers assert that previous information and contact with individuals with disabilities significantly influence students’ attitudes, and they argue that students who possess greater knowledge about disability tend to exhibit more positive and less prejudiced attitudes (

Polo Sánchez et al., 2011;

Polo Sánchez et al., 2018;

Shields et al., 2024). Moreover, they contend that educational interventions emphasizing direct interaction and understanding of disability are effective in fostering better attitudes among students (

Garabal-Barbeira et al., 2018;

Polo Sánchez et al., 2018). In the case of OT, the specificity of the program, which places greater emphasis on interactions and social relationships with people with disabilities, contributes to more positive attitudes. For this reason, education and awareness are fundamental to improving attitudes and promoting inclusion; through comprehensive educational programs, individuals gain a deeper understanding of the challenges faced by people with disabilities, fostering empathy and reducing prejudice (

Moreno Pilo et al., 2022). Prior contact with people with disabilities before the university stage can be circumstantial. However, in Spain, according to statistics from the National Institute of Statistics (

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2024), during the 2022–2023 academic year, approximately 10.6% of students in non-university education required specific educational support. Of this group, 262,732 students had special educational needs associated with some type of disability. This reality has enabled some current university students to have the opportunity to interact with people with disabilities in an educational setting, promoting inclusive experiences from the early stages.

Moreover, students can be distinctly categorized into two groups based on their field of study: the first group includes those in the PASS and ECE fields, traditionally linked to social sciences, and the second one includes those in the OT field, related to health sciences. This classification does not reflect the similarity in their questionnaire responses. A notable trend is that ECE and OT students predominantly achieve very high scores on the scale, whereas the scores among PASS students exhibit greater variability. The critical factor influencing higher overall scores on the scale is identified as the “Social and Interpersonal Relationships” factor. Students who score above 48 in relation to this factor tend to show better overall attitudes toward disability, emphasizing its importance in fostering positive perceptions and attitudes. The differences observed based on the degree program may be attributed to several factors, as ECE and even more OT students are typically more exposed to individuals with disabilities and receive more intensive training on inclusion and empathy, which may foster more positive attitudes (

Au & Man, 2006;

VanPuymbrouck & Friedman, 2020). In opposition, PASS students may have fewer opportunities for such interaction and specific training in the field of disability, leading to greater variability in their scores.

The findings of this study highlight the complex interaction between the academic year and the degree program in shaping students’ attitudes toward disability. Significant differences were observed across several dimensions and the total scale score when comparing first- and fourth-year students within specific degree programs. For instance, first-year students of ECE and OT displayed significantly different attitudes compared to their fourth-year counterparts, particularly in Factor 1 and the Total Score. These findings suggest a maturation or education-driven shift in attitudes over the course of their academic journey, coinciding with previous studies (

García-Fernández et al., 2013), which found that students in the later years of their degree programs exhibited more positive attitudes toward diversity, suggesting that increased exposure and education contribute to more inclusive perspectives. These results, coinciding with previous studies (

Polo Sánchez et al., 2018), underscore the importance of tailoring educational strategies to address and improve attitudes toward disability at different stages of academic progression across various disciplines. Furthermore, upon reviewing the teaching plans across these three degrees programs, interesting discrepancies in the curricular content become evident. In the PASS degree, there is a notable focus on disability-related competencies, particularly CT8, which centers on accessibility and inclusion for individuals with disabilities in the field of physical activity. This competency is integrated into a total of 24 subjects, suggesting a structured approach to fostering an understanding of accessibility within the sports sciences. However, of these 24 subjects mentioning CT8, only 3 include different content or learning outcomes specifically related to people with disabilities, and only 1 subject, “Adapted Physical Activity and Sport”, has a specific study program dedicated to people with disabilities, which is paradoxical given the growing emphasis on promoting inclusion and addressing the needs of people with disabilities in educational and professional training programs. For this reason, it is deemed necessary to review the different educational programs and ensure that they effectively incorporate relevant content. In contrast, the ECE program includes eight specific competencies related to diversity, inclusion, and disability (CG3, CT3.6, CT8, CT12, CE70, CE81, CE83), but these are covered across only 17 subjects. Among these 17 subjects, only 7 include content or learning outcomes specifically related to people with disabilities. Furthermore, ECE has five subjects directly focused on people with disabilities; while some subjects do not mention the competencies, others feature a variety of topics related to disability. While this breadth of competencies reflects a formal commitment to inclusion within the ECE curriculum, it may not translate into the same level of depth or practical exposure as seen in OT. Interestingly, OT includes only one explicit competence related to disability, CE9, addressed in 11 subjects. Despite this, the review of the subject content and learning outcomes reveals that OT courses frequently reference individuals with disabilities or specific disorders, integrating this focus organically throughout the curriculum. This indicates that while OT may not list numerous disability-related competencies explicitly, the curriculum itself is inherently structured to foster a deep understanding of and practical engagement with the population.

Lastly, coinciding with previous findings (

Atoche-Silva et al., 2021;

Moneo Estany & Anaut Bravo, 2017), university students tend to hold generally positive attitudes toward individuals with disabilities, although there are still areas for improvement. Therefore, implementing awareness programs and continuous education is suggested to foster an inclusive culture within both educational and healthcare settings, specifically in OT. These initiatives aim not only to enhance understanding and acceptance but also to create environments where everyone feels valued and respected, regardless of their abilities.

This study may contribute positively to the field of study by providing a nuanced, comparative analysis of university students attitudes across different degrees, adding depth to previous findings. There are a few previous studies that analyze attitudes toward disabilities in university students using this questionnaire; however, they do not specifically examine which scales have the greatest influence on general attitudes across different groups of students. By examining how both the degree program and the academic year impact attitudes, this research underscores the effect of the curriculum content on attitudes, showing that students from programs with more direct exposure to disability, like OT, report more positive attitudes overall. These findings advocate for curricular modifications, emphasizing the importance of specialized training and interaction with individuals with disabilities to foster inclusivity. This highlights the need for reflection on academic curricula, particularly in higher education and university programs, to ensure they adequately prepare students to address the diverse needs of society and promote inclusive practices in their professional fields.

This study’s findings must be interpreted within the context of the potential limitations. Firstly, the sample may limit the generalizability of the results to broader populations of students, especially beyond the regional scope or in other academic fields. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported measures to assess attitudes could be susceptible to social desirability bias, potentially influencing the accuracy of the results.

Future research could explore the long-term impact of tailored coursework and practical training on graduates’ attitudes toward disability as they enter professional education and healthcare fields, with the aim of designing specific continuous training programs. Longitudinal studies tracking students beyond their university years would provide valuable insights into how attitudes evolve and influence behaviors in these settings. Additionally, investigating the effectiveness of specific educational interventions or curriculum modifications in promoting positive attitudes could inform evidence-based strategies for fostering inclusivity in higher education. Exploring the role of factors such as personal experiences, cultural background, and exposure to individuals with disabilities could also provide a better understanding of the determinants of attitudes among university students. Overall, future research should aim to clarify the complex interplay between educational experiences, personal factors, and attitudes toward disability to develop effective interventions and policies in healthcare and education.