The Self-Perceptions of Twice-Exceptional Children: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Definitions

1.2. Current State of Knowledge and Its Uncertainties

1.2.1. Self-Perceptions of Students with Learning Disorder (LD)

1.2.2. Self-Perceptions of Gifted Students

1.3. The Current Review

- What is the self-concept of twice-exceptional children?

- What is the self-esteem of twice-exceptional children?

- What is the self-efficacy of twice-exceptional children?

- Which variables have an influence on self-concept in twice-exceptional children?

- Which variables have an influence on self-esteem in twice-exceptional children?

- Which variables have an influence on self-efficacy in twice-exceptional children?

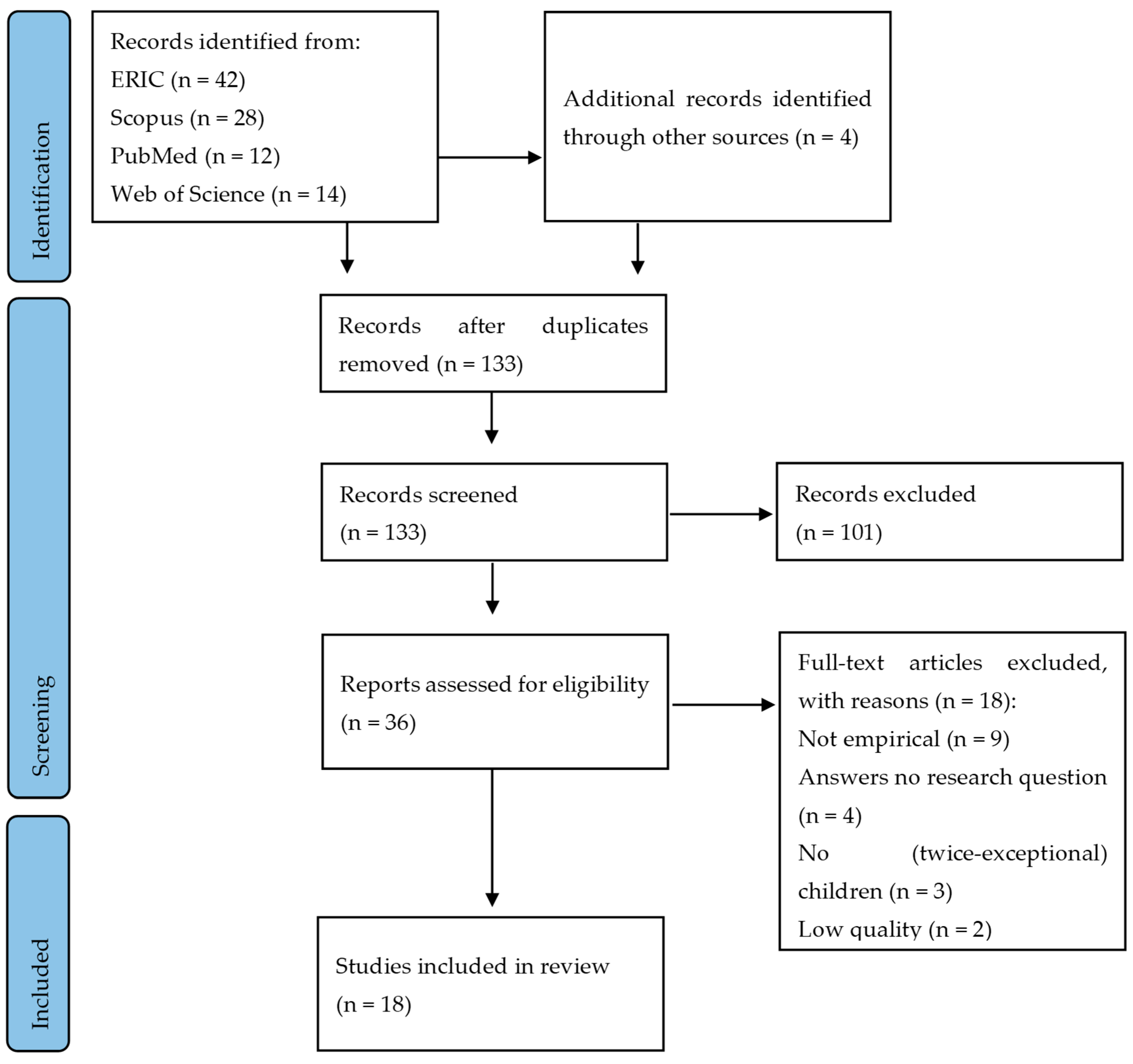

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search

2.2. Screening

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Quality Assessment

3.1.1. Qualitative Papers

3.1.2. Quantitative Papers

3.2. Findings from Papers

3.2.1. Self-Concept of Twice-Exceptional Children

3.2.2. Self-Esteem of Twice-Exceptional Children

3.2.3. Self-Efficacy of Twice-Exceptional Children

3.2.4. Variables with an Influence on Self-Concept in Twice-Exceptional Children

3.2.5. Variables with an Influence on Self-Esteem in Twice-Exceptional Children

3.2.6. Variables with an Influence on Self-Efficacy in Twice-Exceptional Children

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary and Interpretation of the Results

4.2. Limitations

4.2.1. Evidence

4.2.2. Review Process

4.3. Implications for Practice, Policy, and Future Research

4.3.1. Implications for Practice

4.3.2. Implications for Policy

4.3.3. Implications for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acosta, S., Garza, T., & Hsu, H.-Y. (2020). Assessing quality in systematic reviews: A study of novice rater training supplemental material Appendix A methodological quality questionnaire (MQQ) rating scale. SAGE Open. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hroub, A. (2008). Charting self-concept, beliefs and attitudes towards mathematics among mathematically gifted pupils with learning difficulties. Gifted and Talanted International, 23(2), 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yagon, M., & Mikulincer, M. (2004). Socioemotional and academic adjustment among children with learning disorders: The mediational role of attachment-based factors. The Journal of Special Education, 38(2), 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B. N. (2020). “See Me, See Us”: Understanding the intersections and continued marginalization of adolescent gifted black girls in U.S. classrooms. Gifted Child Today, 43(2), 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqilah, H., Rosadah, A., & Majid, A. (2019). Learning strategies for twice-exceptional students. International Journal of Special Education, 33(4), 954–976. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, L., Omdal, S. N., & Pereles, D. (2019). Beyond stereotypes: Understanding, recognizing, and working with twice-exceptional learners. Teaching Exceptional Children, 47(4), 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, C., & Mueller, C. T. (2011). Social and self-perceptions of adolescents identified as gifted, learning disabled, and twice-exceptional. Roeper Review, 33(2), 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudson, T. G., & Preckel, F. (2013). Teachers’ implicit personality theories about the gifted: An experimental approach. School Psychology Quarterly, 28(1), 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baum, S. (1988). An enrichment program for gifted learning disabled students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 32(1), 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, S., & Owen, S. V. (1988). High ability/learning disabled students: How are they different? Gifted Child Quarterly, 32(3), 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, G. G., Minke, K. M., & Manning, M. A. (2002). Self-concept of students with learning disabilities: A meta analysis. School Psychology Review, 31(3), 405–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L., Long, S., Garvan, C., & Bussing, R. (2011). The impact of teacher credentials on ADHD Stigma Perceptions. Psychology in the Schools, 48(2), 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, L. J. (2017). Self-esteem and locus of control: A longitudinal analysis of twice-ecveptional learners. The Florida State University. [Google Scholar]

- Bong, M., & Clark, R. E. (1999). Comparison between self-concept and self-efficacy in academic motivation research. Educational Psychologist, 34(3), 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bong, M., & Skaalvik, E. M. (2003). Academic self-concept and self-efficacy: How different are they really? Educational Psychology Review, 18(1), 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casino-García, A. M., Llopis-Bueno, M. J., & Llinares-Insa, L. I. (2021). Emotional intelligence profiles and self-esteem/self-concept: An analysis of relationships in gifted students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheek, C. L., Garcia, J. L., Mehta, P. D., Francis, D. J., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2023). The exceptionality of twice-exceptionality: Examining combined prevalence of giftedness and disability using multivariate statistical simulation. Exceptional Children, 90(1), 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, L. J., Micko, K. J., & Cross, T. L. (2015). Twenty-five years of research on the lived experience of being gifted in school: Capturing the students’ voices. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 38(4), 358–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, E. E., Ness, M., & Smith, M. (2004). A case study of a child with dyslexia and spatial-temporal gifts. Gifted Child Quarterly, 48(2), 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Larson, R. (1987). Validity and reliability of the experience-sampling method. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 175(9), 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, K., & Sansour, T. (2024). Self-concept and achievement in individuals with intellectual disabilities. Disabilities, 4(2), 348–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley-Nicpon, M., Allmon, A., Sieck, B., & Stinson, R. D. (2011). Empirical investigation of twice-exceptionality: Where have we been and where are we going? Gifted Child Quarterly, 55(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley-Nicpon, M., Assouline, S. G., & Fosenburg, S. (2015). The relationship between self-concept, ability, and academic programming among twice-exceptional youth. Journal of Advanced Academics, 26(4), 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley-Nicpon, M., & Candler, M. M. (2017). Psychological interventions for twice-exceptional youth. In APA handbook of giftedness and talent (pp. 545–558). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley-Nicpon, M., Rickels, H., Assouline, S. G., & Richards, A. (2012). Self-esteem and self-concept examination among gifted students With ADHD. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 35(3), 220–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, C. M., & Gentry, M. (2016). Understanding adolescent gifted girls with ADHD: Motivated and achieving. High Ability Studies, 27(1), 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginevra, M. C., Di Maggio, I., Valbusa, I., Santilli, S., & Nota, L. (2022). Teachers’ attitudes towards students with disabilities: The role of the type of information provided in the students’ profiles of children with disabilities. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 37(3), 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, L. A. (2022). A phenomenological study: The self-efficacy of twice-exceptional students [Ph.D. thesis, School of Education]. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogeveen, L., Van Hell, J. G., & Verhoeven, L. (2009). Self-concept and social status of accelerated and nonaccelerated students in the first 2 years of secondary school in the Netherlands. Gifted Child Quarterly, 53(1), 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, C. B. (2002). Career self-efficacy of the student who is gifted/learning disabled: A case study. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 25(4), 375–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huitt, W. (2009). Self-concept and self-esteem. Educational Psychology Interactive. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, N. (2002). Teacher and pupil ratings of self-esteem in developmental dyslexia. British Journal of Special Education, 29(1), 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarwan, F. (2001). Personal and family factors discriminating between high and low achievers on the TIMSS-R. The National Center for Human Resources Development (NCHRD). [Google Scholar]

- Kavale, K. A., & Forness, S. R. (1966). Social skill deficits and learning disabilities: A meta-analysis. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 29(3), 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krischler, M., & Pit-ten Cate, I. M. (2019). Pre- and in-service teachers’ attitudes toward students with learning difficulties and challenging behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, L. R. (2021). Twice-exceptionality: Maximizing academic & psychosocial success in youth. Journal of Health Service Psychology, 47(4), 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), W-65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litster, K., & Roberts, J. (2011). The self-concepts and perceived competencies of gifted and non-gifted students: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 11(2), 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M., Hosman, C. M. H., Schaalma, H. P., & De Vries, N. K. (2004). Self-esteem in a broad-spectrum approach for mental health promotion. Health Education Research, 19(4), 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendaglio, S. (2013). Gifted students’ transition to university. Gifted Education International, 29(1), 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, A. N., & Hamilton, L. T. (2021). The stigma of ADHD: Teacher ratings of labeled students. Sociological Perspectives, 64(2), 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missett, T. C., Azano, A. P., Callahan, C. M., & Landrum, K. (2016). The influence of teacher expectations about twice-exceptional students on the use of high quality gifted curriculum: A case study approach. Exceptionality, 24(1), 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olenchak, R. F. (1995). Effects of enrichment on gifted/ learning-disabled students. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 18(4), 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, S. V., & Baum, S. M. (1985). Development of an academic self-efficacy scale for upper elementary school children [unpublished manuscript]. University of Connecticut. [Google Scholar]

- Peperkorn, C., & Wegner, C. (2020). The big-five-personality and academic self-concept in gifted and non-gifted students: A systematic review of literature. International Journal of Research in Education and Science (IJRES), 6(4), 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, S. M., Baum, S. M., & Burke, E. (2014). An operational definition of twice-exceptional learners: Implications and applications. Gifted Child Quarterly, 58(3), 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzulli, J. S. (1977). The enrichment triad model: A guide for developing defensible programs for the gifted and talented. Creative Learning Center. [Google Scholar]

- Ronksley-Pavia, M., Grootenboer, P., & Pendergast, D. (2019a). Bullying and the unique experiences of twice exceptional learners: Student perspective narratives. Gifted Child Today, 42(1), 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronksley-Pavia, M., Grootenboer, P., & Pendergast, D. (2019b). Privileging the voices of twice-exceptional children: An exploration of lived experiences and stigma narratives*. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 42(1), 4–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shany, M., Wiener, J., & Assido, M. (2013). Friendship predictors of global self-worth and domain-specific self-concepts in university students with and without learning disability. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 46(5), 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowislo, J. F., & Orth, U. (2013). Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 139(1), 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swann, W. B., Chang-Schneider, C., & McClarty, K. L. (2007). Do people’s self-views matter? Self-concept and self-esteem in everyday life. American Psychologist, 62(2), 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townend, G., & Brown, R. (2016). Exploring a sociocultural approach to understanding academic self-concept in twice-exceptional students. International Journal of Educational Research, 80, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townend, G., & Pendergast, D. (2015). Student voice: What can we learn from twice-exceptional students about the teacher’s role in enhancing or inhibiting academic self-concept. The Australasian Journal of Gifted Education, 24(1), 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2020). Global education monitoring report 2020: Inclusion and education: All means all. UNESCO. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- VanTassel-Baska, J., Feng, A. X., Swanson, J. D., Quek, C., & Chandler, K. (2009). Academic and affective profiles of low-income, minority, and twice-exceptional gifted learners: The role of gifted program membership in enhancing self. Journal of Advanced Academics, 20(4), 702–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vespi, L., & Yewchuk, C. (1992). A phenomenological study of the social/emotional characteristics of gifted learning disabled children. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 16(1), 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, K. A., Saphire, D. G., & Rosenblum, S. A. (1987). Learning disabilities and giftedness: Identification based on self-concept, behavior, and academic patterns. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 20(7), 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C. W., & Neihart, M. (2015a). Academic self-concept and academic self-efficacy: Self-beliefs enable academic achievement of twice-exceptional students. Roeper Review, 37(2), 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. W., & Neihart, M. (2015b). How do supports from parents, teachers, and peers influence academic achievement of twice-exceptional students. Gifted Child Today, 38(3), 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H., Guo, Y., Yang, Y., Zhao, L., & Guo, C. (2021). A meta-analysis of the longitudinal relationship between academic self-concept and academic achievement. Educational Psychology Review, 33(4), 1749–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

|

|

| Quality Rating | Qualitative Paper | Quantitative Paper |

|---|---|---|

| Low 0–9 | (Baum, 1988; Cooper et al., 2004; VanTassel-Baska et al., 2009) | |

| Medium 10–18 | (Foley-Nicpon et al., 2012; Fugate & Gentry, 2016; Olenchak, 1995; Vespi & Yewchuk, 1992) | (Baum & Owen, 1988; Hua, 2002) |

| High 19–27 | (Ronksley-Pavia et al., 2019b; Townend & Brown, 2016; Townend & Pendergast, 2015; Wang & Neihart, 2015a, 2015b) | (Al-Hroub, 2008; Barber & Mueller, 2011; Foley-Nicpon et al., 2015; Waldron et al., 1987) |

| Location | N | Gender (M:F) | Age (Years) | Operationalization Giftedness | Operationalization Learning Difficulties | Methodology 1 | Measure | Concepts 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Al-Hroub, 2008) | Jordan | 30 | 14:16 | 10–11 | Multi-dimensional evaluation process | NR 3 | MMs | MaSAS 4 interviews | SC (-) |

| (Barber & Mueller, 2011) | United States | 360 | 263:97 | M = 15,23 | Peabody Picture Vocabulary test (AHPVT) ≥ 120 | Parents reported learning disability | Quan | NR | SC (-) |

| (Baum & Owen, 1988) | Connecticut | 112 | NR | NR | IQ ≥ 120 (WISC-R) Performance/Verbal Scales, were classified as gifted by their local school district | Selected from the existing learning-disabled population in the local districts | Quan | SE for academic tasks (Owen & Baum, 1985) | Ac SE (-) |

| (Baum, 1988) | Connecticut | 7 | 5:2 | NR | Performance or verbal scale ≥ 120 | Performed below grade level, discrepancy between ability and achievement | Qual | Interviews | SEst |

| (Cooper et al., 2004) | New England | 1 | 1:0 | NR | WISC-III overall score of 124 | Diagnosed with dyslexia | Qual, CS | NR | SEst, SE |

| (Foley-Nicpon et al., 2012) | Iowa | 112 | 2e: 75:37, gifted: 74:38 | 6–18 | IQ ≥ 120 (WISC-IV) | Diagnosed with ADHD | Quan | BASC-2, PH-2 | SEst (-), SC (-) |

| (Foley-Nicpon et al., 2015) | Iowa | 64 | ASD: 52:12; SLD: 41:23 | 5–17 | IQ ≥ 120 (WISC-IV) | Criteria for an ASD or SLD consistent with the DSM-IV-TR | Quan | PH-2 | SC (/) |

| (Fugate & Gentry, 2016) | United States | 5 | 0:5 | M = 12.6 | Ability score ≥ 120; overall ≥ 90th percentile on normed tests of achievement or ability; or ≥70th percentile on any one sub-test | Diagnosed with ADHD | Qual, CS | Interview | SEst, SE |

| (Hua, 2002) | United States | 1 | 1:0 | NR | IQ of 135 | Perceptual–communicative disorder due to sensory–motor integration problems | Qual, CS | Interview | SE |

| (Olenchak, 1995) | United States | 108 | 82:26 | NR | IQ ≥ 120 | Need service for learning disabilities | Quan | PH-2 | SC |

| (Ronksley-Pavia et al., 2019b) | Australia | 8 | 5:3 | 9–16 | Giftedness through WISC-IV or WPPSI-R oder WISC-III (one ≥ 120) | Disability diagnosis | Qual, CS | Interview | SEst, SE |

| (Townend & Brown, 2016) | Australia | 1 | 1:0 | 16 | >90th percentile in one or more IQ subscales | Auditory processing disorder diagnosis | MMs, CS | BASC-2, PH-2, Interview | SEst (-), Ac SC (-) |

| (Townend & Pendergast, 2015) | Australia | 3 | 3:0 | NR | WISC-IV or Stanford Binet Fifth Edition, subscale ≥ 120 | Auditory processing disorder diagnosis | MMs, CS | BASC-2, PH-2, interview | SC (-) |

| (VanTassel-Baska et al., 2009) | Singapore | 14 | NR | NR | Standardized ability, achievement, and value-added performance task measures | Through performance task | Qual | Interview | SEst (-) |

| (Vespi & Yewchuk, 1992) | NR | 3 | 3:0 | M = 10.25 | IQ ≥ 120 on one scale of the WISC-R, verbal/performance discrepancy | Identified academic difficulties and receives assistance | Qual | Interview | SEst (+) |

| (Waldron et al., 1987) | Texas | 48 | 24:24 | 8–12 | IQ ≥ 120, or met all criteria for gifted placement in that district | Scored below the 70th percentile, with an uneven profile of scores | Quan | PH-2 | SC (-) |

| (Wang & Neihart, 2015a) | Singapore | 6 | 6:0 | M = 13.83 | Enrollment in GEP, performance within the 75th to 100th percentile | Diagnosed disability | Qual | Interview | Ac SE (+), Ac SC (+) |

| (Wang & Neihart, 2015b) | Singapore | 6 | 6:0 | M = 13.83 | Talent development program | Diagnosed disability | Qual | Interview | SE |

| Positive | Negative | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Enrichment Programs | Focus on Strengths (Teachers) | Supportive Teachers | Supportive Parents | Early Identification | Good Performance | Working with Others | Gifted Program | Traditional Teaching | Negative Relationship (Parents) | Feeling Different | Impatience, Lack of Understanding (Teachers) | Too High Expectations | Late/No Identification | Focus on Deficits (Teachers) | Discrepancy Ability and Performance | Negative Interactions (Teachers, Peers) | Negative Self-Talk | Lack of Social Relationships | Behavioral Problems | Lack of Support (Teachers) | Lack of Recognition (Parents) |

| (Al-Hroub, 2008) | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (Barber & Mueller, 2011) | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| (Baum & Owen, 1988) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Baum, 1988) | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| (Cooper et al., 2004) | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (Foley-Nicpon et al., 2012) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Foley-Nicpon et al., 2015) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Fugate & Gentry, 2016) | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| (Hua, 2002) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| (Olenchak, 1995) | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (Ronksley-Pavia et al., 2019b) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| (Townend & Brown, 2016) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Townend & Pendergast, 2015) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| (VanTassel-Baska et al., 2009) | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (Vespi & Yewchuk, 1992) | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| (Waldron et al., 1987) | x | |||||||||||||||||||||

| (Wang & Neihart, 2015a) | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| (Wang & Neihart, 2015b) | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Küry, L.; Fischer, C. The Self-Perceptions of Twice-Exceptional Children: A Systematic Review. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15010044

Küry L, Fischer C. The Self-Perceptions of Twice-Exceptional Children: A Systematic Review. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleKüry, Louise, and Christian Fischer. 2025. "The Self-Perceptions of Twice-Exceptional Children: A Systematic Review" Education Sciences 15, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15010044

APA StyleKüry, L., & Fischer, C. (2025). The Self-Perceptions of Twice-Exceptional Children: A Systematic Review. Education Sciences, 15(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15010044