1. Introduction

Ukraine offers the image of a country that seeks to join the European educational community. Hence, the quality of foreign language education at both universities and schools must be of a high standard. Apart from the activity of the quality assurance bodies, this can be achieved through enhancing the quality of classroom assessments carried out by teachers. Consequently, teachers need to be better prepared for assessments, which may be achieved during their pre-service training at universities.

In Ukraine, there are 38 tertiary institutions where students major in foreign language (FL) teaching. Various foreign languages are taught with English, French, German, Spanish, Italian, Turkish, Hebrew, Chinese, and Japanese among them. Most of the universities teach the first foreign language alongside a second foreign language. In accordance with the definition of the profile of the specialty given by the Ministry of Science and Education of Ukraine, students are trained in order to become teachers in secondary schools. The typical compulsory foreign languages taught in schools are English, French, Spanish, and German. Moreover, these four languages are represented in ZNO, a school leaving exam required for admission to undergraduate university courses. The English language test is the most popular choice, opted for by more than 100,000 school leavers annually. It should be mentioned that the formats in the ZNO test vary for different foreign languages. Thus, students are to be prepared not only to teach but also to assess these languages and train their learners for taking a matriculation examination.

Apart from disciplines commonly taught to future teachers in 14 universities, there is a stand-alone course on language assessment and testing for students majoring in English and in only two for those majoring in French. No evidence of courses for other foreign languages has been found. The question then arises, “Does the content of language assessment training students undergo reflect the diverse needs of teachers of different languages?”

To address the issue of language assessment literacy (LAL) preparation of pre-service FL teachers, this study explored robust differences in LAL needs across in-service teachers of French and English as a second language working in secondary schools and universities in Ukraine. Their assessment needs were compared and contrasted. Pedagogical cultures underlie the revealed differences. Implications were drawn for the training of pre-service teachers of English and French, the most popular FLs taught in Ukrainian schools. The results can contribute to understanding LAL needs across the two languages.

My hypothesis was that teachers of different foreign languages do have different assessment needs and, thus, require customized training. The hypothesis builds on my experience of teaching English and French and the course on language assessment to students majoring in teaching the two FLs and my experience of being an item writer and reviewer for the ZNO matriculation exam.

Due to my concerns about the content of the course at the initial stage of its design, I contemplated the possibility of teaching it to students majoring in English and French in a different way.

To ease my concerns and inform my decisions on the content of the course, this study was conducted to address the following research questions:

To what extent do English and French teachers feel they need training in language testing and assessment?

Do English and French teachers differ in the task formats they use?

Do English and French teachers differ in the weight they assign to various assessment criteria?

Thus, the purpose of the paper is to present assessment practices of Ukrainian teachers of English and French as a second language and uncover the differences due to pedagogical cultures of these cohorts.

2. Literature Review

There is a growing interest of assessment community in language assessment literacy, which has generated research of its diverse aspects from the perspective of various stakeholders. LAL of foreign language teachers is considered to be a significant component of their expertise by

Boyd and Donnarumma (

2018),

Brookhart (

2011),

Kremmel and Harding (

2020),

Popham (

2009), and

Weng and Shen (

2022). However,

Weng and Shen’s (

2022) overview of the studies dedicated to this issue and published from 1991 to 2021 witnesses that there have been relatively few studies examining teachers’ LAL.

It is acknowledged that FL teachers’ LAL needs are context dependent (

Kremmel & Harding, 2020;

Taylor, 2013;

Vogt et al., 2020). Contextual factors determined by the researchers are numerous, including educational contexts/systems (

Crusan et al., 2016;

Vogt et al., 2020), public and political influences (

Black & William, 2005), profiles of different stakeholders groups (

Cooke et al., 2017;

Kremmel & Harding, 2020;

Taylor, 2009,

2013), level of teachers’ preparation (

Afshar & Ranjbar, 2021;

Sultana, 2019), and their teaching experience (

Crusan et al., 2016). Undoubtedly, all these factors play an equally important role in shaping training needs and thus must be addressed to the benefit of stakeholders. The relationship between LAL and the target language has not been investigated despite a substantial scope of publications on linguistic particularities of languages and evidently different content of existing FL textbooks. Yet pedagogical cultures have not been considered. Among individual factors influencing teachers’ LAL,

Crusan et al. (

2016) operationalize teachers’ linguistic backgrounds, by which they mean being non-native English-speaking and native English-speaking teachers, taking into account the issue of the teacher’s first language. Thus, no previous studies have explored such a contextual factor as a target foreign language of an assessor. Its capacity in developing LAL may have been overlooked, although this contextual factor is apparent in everyday classroom assessment practices. Its impact on LAL training needs may become evident through deeper reflection of the teaching of a particular foreign language since assessment is an integral part of it. Assessment methods, formats, and procedures are to correlate with those of teaching. Studying practices of teachers of different foreign languages may provide a better understanding of existing similarities or differences. The study is intended to contribute to the elaboration of more efficient teacher education programs.

There is a need to point out that English has been the focus of much LAL research. But what about other languages? Is there a possibility that LAL needs might differ depending on the language being taught and assessed? These, in my experience, do differ. This raises the “big” question: Are models of LAL applicable across different language teaching contexts?

The overview of the French and English literature helped to discover the lack of materials on test design for languages other than English. There are

Manuel pour l’élaboration et la passation de tests et d’examens de langue by

ALTE (

2011) and

Les lignes directrices d’EALTA pour une Bonne Pratique dans l’élaboration/utilisation des tests et l’évaluation en langues (

EALTA, 2011). These documents are translated into French; however, they do not provide any guidelines for choosing an appropriate format, writing a rubric, or text adaptation specific for the French language. Even the term LAL itself does not have a commonly accepted equivalent in the French language.

When being on the lookout for a term to describe the differences in assessment carried out by Ukrainian teachers of English and French, I concentrated on searching the collocations with

culture since my assumption was that culture itself accounts for these differences. Analyses of the studies on language assessment revealed that there is no agreed interpretation of the term “assessment culture”; moreover, there is not enough evidence of how it is related to a target language.

Sultana (

2019) uses the term “a test-oriented [assessment] culture”, meaning that teachers in Bangladesh rely heavily on tests for grading.

Tsagari (

2021) uses the term “assessment cultures” to describe the role of assessment. The subsequent study prompted a shift to the collocations with

pedagogy in an attempt to find evidence that its methods, approaches, and principles vary in line with a foreign language taught by teachers.

Following one of the LAL dimensions proposed by

Taylor (

2013), namely, “language pedagogy”,

Kremmel and Harding (

2020) use this term to label the use of assessments in teaching and learning contexts as assessments in language pedagogy. However, no evidence is provided by the researchers to support in what way a foreign language influences assessment.

Taylor (

2013) hypothesizes that language pedagogy would be important for language teachers in terms of LAL, but does not elaborate this idea.

Knausz (

2018) uses the expression “pedagogical culture” as a synonym of teachers’ mentality including the ways of thinking, beliefs, convictions, and intentions that the individuals of a given culture have in common, just further referring to it by the simplified term “beliefs”.

Myllykoski-Laine et al. (

2023) use “pedagogical culture” to describe how the Finnish university community is organized.

Esch (

2012) studied pedagogical cultures of Cameroonian primary school teachers speaking English or French as their native language and using them as their medium of instruction, focusing on their behavior and communication with colleagues and pupils.

I suggest using the term “pedagogical culture” to name the way a foreign language is taught or assessed. Taking into consideration traditions of teaching modern languages may facilitate the development of LAL of student teachers and ensure adequate guidance of assessment procedures, which will be good support for future FL teachers. By doing so, we can enable students to rely on their previous language experience and eliminate uncertainties that may arise in mastering LAL. Students can be more effectively involved in acquiring assessment literacy.

Cultural traditions in teaching different modern languages may influence (a) the content of texts, (b) the range of task formats, (c) the weighting of different criteria, and even (d) attitudes toward assessment. Therefore, to understand teachers’ LAL needs, we should take into account specific language pedagogies.

Reviewing the content of the course on language testing and assessment for pre-service teachers in Kharkiv Skovoroda National Pedagogical University necessitated answering the question, “Do English and French teachers have similar or different assessment needs?” In my present study, I explore the idea of the importance of pedagogical culture. Pedagogical cultures affect the way FL teachers are trained, relying on the traditions of teaching a foreign language. Thus, they form the concept of FL assessment.

3. Materials and Methods

In order to prove the hypothesis, data were collected in a mixed method study including a survey, an interview, documents analysis, and comparative analysis.

English and French as a second language teachers’ responses were collected in the survey. The respondents completed a questionnaire and took part in follow-up semi-structured interviews immediately after the completion of the questionnaire to gather feedback and gain a comprehensive understanding of their responses since teachers may respond unconsciously, meeting the standards and not exposing their real practice. The interviews were not recorded in order to encourage the teachers to share their stories, but notes were taken to fix their answers and comments. In addition, English (n = 43) and French (n = 26) textbooks recommended by the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine for use at secondary schools (the list is available on the Ministry’s website), ZNO English and French tests for school-leavers, and international English and French proficiency tests (IELTS, Cambridge exam suite; DELF, DALF, TEF, and TCF) often used for teaching and assessment purposes by FL teachers were analyzed using the qualitative method to explore typical task formats for both languages.

Only completed questionnaires were subject to analysis. The questionnaire and interview results were analyzed using descriptive statistics and visualizations. They were used to identify areas in which English and French teachers might differ. The number of responses for each item was transferred into a percentage with the idea of further comparing the data across the two languages. The results of the analysis of the documents provided more insightful data for the comparison of assessment practices of Ukrainian teachers.

There were two stages of the survey. The first stage was in 2018, and then the survey with the updated versions of the questionnaire was repeated in 2024.

The respondents were approached and contacted through personal networks. They were informed about the purpose of the study. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. The participants of the survey were French (n = 30) and English (n = 40) university and school teachers from eastern and central parts of Ukraine. They were all females and Ph.D. holders with more than 15 years of teaching experience. Three of them were certified DELF examiners.

The questionnaire was developed by the researcher herself. It consisted of three parts. The first part contained background questions about the type of the educational institution, the foreign language taught, the level of education, general teaching experience, and professional training in assessment. The second part comprised 14 open- and closed-ended questions targeting the teachers’ assessment practices. The third part included questions about challenges related to assessments and needs for professional training in assessment. The language used in the survey was Ukrainian so as to avoid the challenges imposed by translating the terminology into two different languages.

The repertoire of the questions in the second part was based on the content of modern textbooks on FL teaching published in Ukraine and the fundamentals of classroom language assessment (for example,

Manuel pour l’élaboration et la passation de tests et d’examens de langue by

ALTE (

2011). The list of the aspects included in the questionnaire is presented below:

The origin of assessment tasks (ready-made, adapted, or self-designed);

Task types and formats typical for testing listening, reading, writing, and speaking skills;

Purposes and frequency of assessments;

Frequency of writing items;

The purpose of writing items (for formative or summative assessment, language contests, accreditation, or text books);

The format of self-designed items (teacher assessment, self- or peer assessment; computerized or paper and pen tests; written or oral; individual, group, or paired; for testing reading, listening, writing, speaking, or use of language);

The criteria for selecting ready-made tasks;

Difficulties faced when selecting, adapting, or designing tasks for assessment purposes;

Weighting of assessment criteria.

After each question, there was some space provided for comments if necessary.

4. Results

In order to receive answers to research question 1, “To what extent do English and French teachers feel they need training in language testing and assessment?”, the teachers were asked the question, “Do you feel the need for training in assessment and testing?” in the questionnaire.

Figure 1 presents the percentage of respondents who agreed with the statement.

“To what extent do English and French teachers feel they need training in language testing and assessment?”

As can be seen from the graph, more than half of the surveyed English teachers feel the need for training, while the teachers of French mainly answered “no”. Those French teachers who picked “maybe” did so because they could not think of anything in terms of assessment about which they would like to get into the nitty-gritty. Being part of the French teachers’ community myself and relying on the comments, I was able to come to the conclusion that this is like that because of their unconscious competence or unconscious incompetence (after N. Burch).

Here are some comments given by the teachers. Most of the English teachers expressed their eagerness to learn more about assessment, “I never refuse to acquire professional knowledge” and “We all need to learn to assess more objectively”, while the teachers of French made comments such as “I’m qualified enough”. They either wrote it in the questionnaire or said more or less the same when interviewed.

In line with research question 2, “Do English and French teachers differ in the task formats they use?”, the teachers were asked about what tests they used for assessment.

Figure 2 presents the percentage of respondents who selected each category.

“What do teachers use for assessment?”

According to the received data, the lower percentage use ready-made tests from materials for preparation for proficiency tests or past papers or adapt them. For the teachers of French, adaptation means analysis of the text for reading, and for the English teachers, it is mainly reducing the number of items. Curiously enough, it turned out that the high percentage of those who design tests do this for testing vocabulary and grammar to address better the material they taught.

Below you can find

Table 1 with the data summarizing the Ukrainian context of teaching and assessment of English and French.

University teachers of English as the first FL normally teach larger classes. French is mainly taught as a second FL after English, but most of the teachers do not rely on the knowledge and experience their students have acquired despite a large amount of research conducted by Ukrainian scholars dedicated to teaching a second foreign language after a certain first FL. The French materials in the textbooks and international tests are more focused on France and its culture. French school textbooks include texts about Ukraine. The range of genres and text formats of French texts for reading is much wider, including dialogues, letters, poems, and songs. Meanwhile, those who teach English have a much wider choice of extra materials online.

The interviews revealed that the French teachers difficulty with understanding constructs, for example, differentiating items for testing reading or listening for specific information and those for detailed understanding. They also use a lot of formats for assessment, formats traditionally considered by English teachers to be more suitable for teaching, e.g., “write True or False and explain your choice”. The teachers of English fail to inform their students regularly of the assessment criteria in contrast to the teachers of French. This is explained by the fact that almost all the students majoring in French take proficiency tests and successfully pass them at levels C1 and C2.

Further, there are graphs showing the most typical task types used by the teachers for assessing different skills. There are task types favored by the teachers of both languages, yet there are some differences in their preferences. For example, for speaking, both groups choose individual long turn, open-ended questions; agree–disagree statements; and role plays. Although the graph shows a wider range of formats used by the teachers of English, the French teachers use a large variety of tasks too, but interestingly, they are not aware of specific names of the formats. The teachers of English use retelling for testing speaking, while the teachers of French use this task type for testing writing, reading, and listening.

Figure 3 presents the results of the responses to the question, “Which task types do you often use for assessing speaking?” in percentage.

“Which task types do you often use for assessing speaking?”

Figure 4 presents the results of responses to the question, “Which task types do you often use for assessing writing?” in percentage.

“Which task types do you often use for assessing writing?”

This picture is close to reality. Indeed, French teachers use a larger variety of tasks for testing writing, including one that is never practiced by English teachers—synthesis. However, it is in line with the recent trend of integrated testing.

Figure 5 presents the results of responses to the question, “Which task types do you often use for assessing reading?” in percentage.

“Which task types do you often use for assessing reading?”

For testing reading, English teachers opt for true/false, multiple choice questions, matching, and gap-filling or completion. French teachers assess with the help of true/false as well and with table completion, short and open-ended answers and synthesis again the task type not exploited by the English teachers. I would like to draw the attention to the fact that the surveyed French teachers never use matching.

Figure 6 presents the results of responses to the question, “Which task types do you often use for assessing listening?” in percentage.

“Which task types do you often use for assessing listening?”

For testing listening, the results are similar. True/false and multiple choice questions are mainstream task types. French teachers use a wider repertoire of task types.

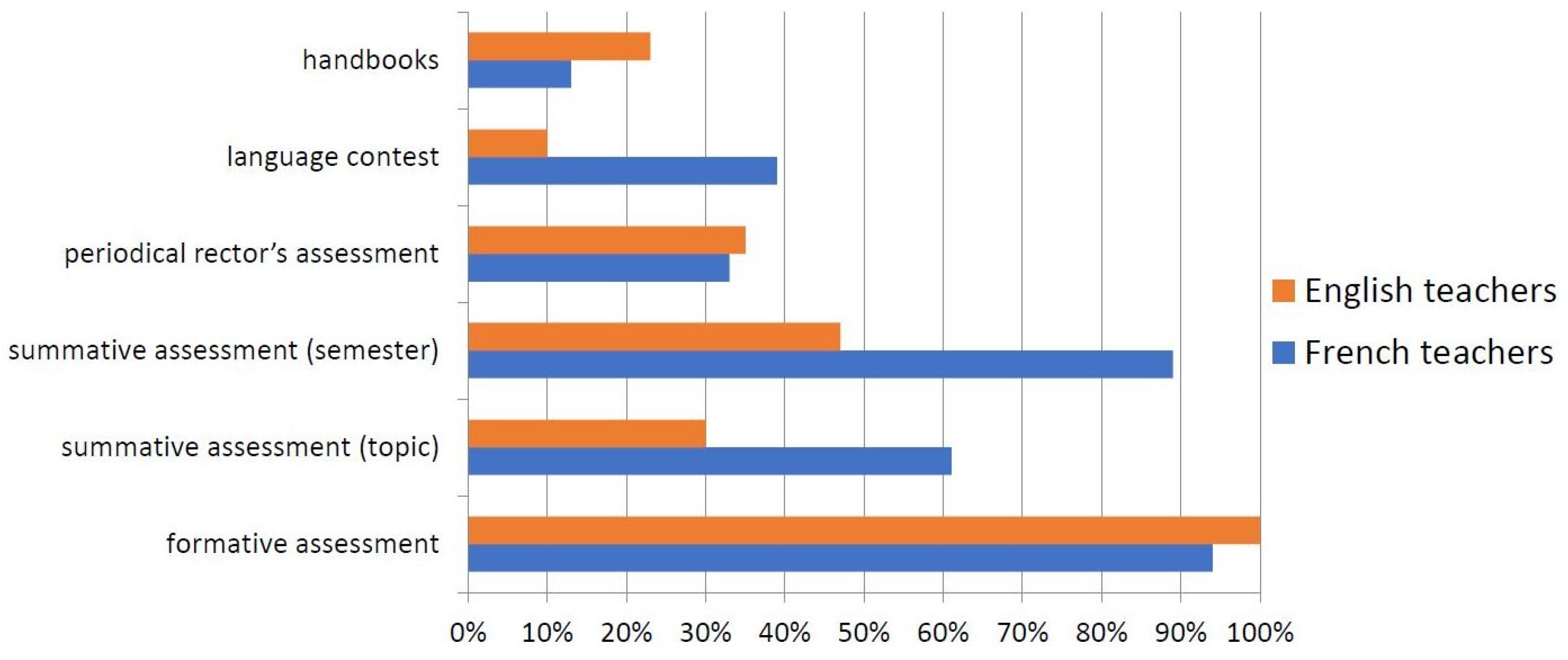

Figure 7 presents the results of responses to the question, “Why do you design tests?” in percentage.

“Why do you design tests?”

The majority of teachers of English design their own tests for formative assessment, while the teachers of French do it also for summative assessment and language contests due to the lack of ready-made materials.

Figure 8 presents the results of responses to the question, “Which aspect do you often design tests for?” in percentage.

“Which aspect do you often design tests for?”

As you can see, most of the teachers of French often design tests for assessing vocabulary and grammar and a little less often for the other aspects, while the teachers of English design their own tests for assessing vocabulary and less often for testing speaking and writing.

Figure 9 presents the results of responses to the question, “Which task types do you often design?” in percentage.

“Which task types do you often design?”

Both groups of teachers design true/false, translation, open-ended questions, individual long turn, gap filling, agree–disagree statements. The task type also preferred by the teachers of English is transformation, while the task types preferred by the teachers of French is letter writing, short answer, MCQ, compositions, and essays.

Figure 10 presents the results of responses to the question, “Which difficulties do you face when designing tests?” in percentage.

“Which difficulties do you face when designing tests?”

The teachers of French experienced fewer difficulties when designing tests, showing more confidence in their assessment expertise. The teachers of English cared about more aspects when designing assessments. To illustrate this, I present a comment by a French teacher: “I do not have any difficulties as I have experience and underwent training”.

My research question 3 was, “Do English and French teachers differ in the weight they assign to various assessment criteria?” Below you can find the results in percentage in

Figure 11.

“Rate the weight of speaking criteria (8—most important, 1—least important).”

When asked to rate the weight of speaking criteria, both groups of teachers claimed to pay the same attention to task achievement. The teachers of French focus on pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary, paying little attention to fluency, while the teachers of English focus more on grammar than vocabulary but pay more attention to fluency and coherence and cohesion. The amount of time their students can speak is also meaningful for them.

Figure 12 presents the results of rating the weight of writing criteria.

“Rate the weight of writing criteria (8—most important, 1—least important).”

As for writing, the teachers of French value task achievement and grammar with little focus on style and no focus on the number of words. The teachers of English focus more or less equally on all the criteria.

As mentioned above, I analyzed a wide range of materials used by English and French teachers—textbooks recommended by the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, ZNO tests for school-leavers, and international proficiency tests.

Table 2 summarizes the range of the task types of both languages preferred by the teachers and those represented in textbooks and international tests. The green, blue, yellow, and gray highlighted text shows matches/similarities for reading (R), listening (L), speaking (S), and writing (W), correspondingly. It should be mentioned that the ZNO French test format was changed two years ago; thus, the matching task type was introduced for reading for gist and reading for specific information. It was done with idea of unifying English and French ZNO tests. However, this format normally is not used by French teachers for teaching purposes, which caused problems in item writing.

The results confirm that textbooks and proficiency tests drive teachers’ behavior. The repertoire of task types varies due to different pedagogical approaches. Interestingly, students learning both languages adjust to different assessment practices of their teachers and experience no difficulties in switching between requirements.