Rethinking Economics Education: Student Perceptions of the Social and Solidarity Economy in Higher Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Role of the Higher Education Institutions and University Social Responsibility

2.2. Teaching in Heterodox Economics; The Social and Solidarity Economy and Higher Education Institutions

2.2.1. Teaching Pluralist Economics in HEIs

2.2.2. Potentials of the SSE in the Higher Education Framework

3. AIMS

Aims of the Study

- -

- Identify the representations of FEB students at the University of the Basque Country regarding what the SSE is and what it involves, as a tool for the transmission of ethical values and principles.

- -

- Identify students’ prior knowledge and its connection with formal knowledge in the field of the social and solidarity economy (SSE).

- -

- Identify the potentials and complementarities of inserting the SSE into the teaching of economics and business.

4. Methodology

4.1. Text Analysis

4.1.1. Participants

4.1.2. Procedure

4.1.3. Design

4.1.4. Instrument

4.1.5. Data Analysis

4.2. Similarity Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Text Analysis: Representations Regarding What Faculty of Economics and Business Students Understand by the SSE

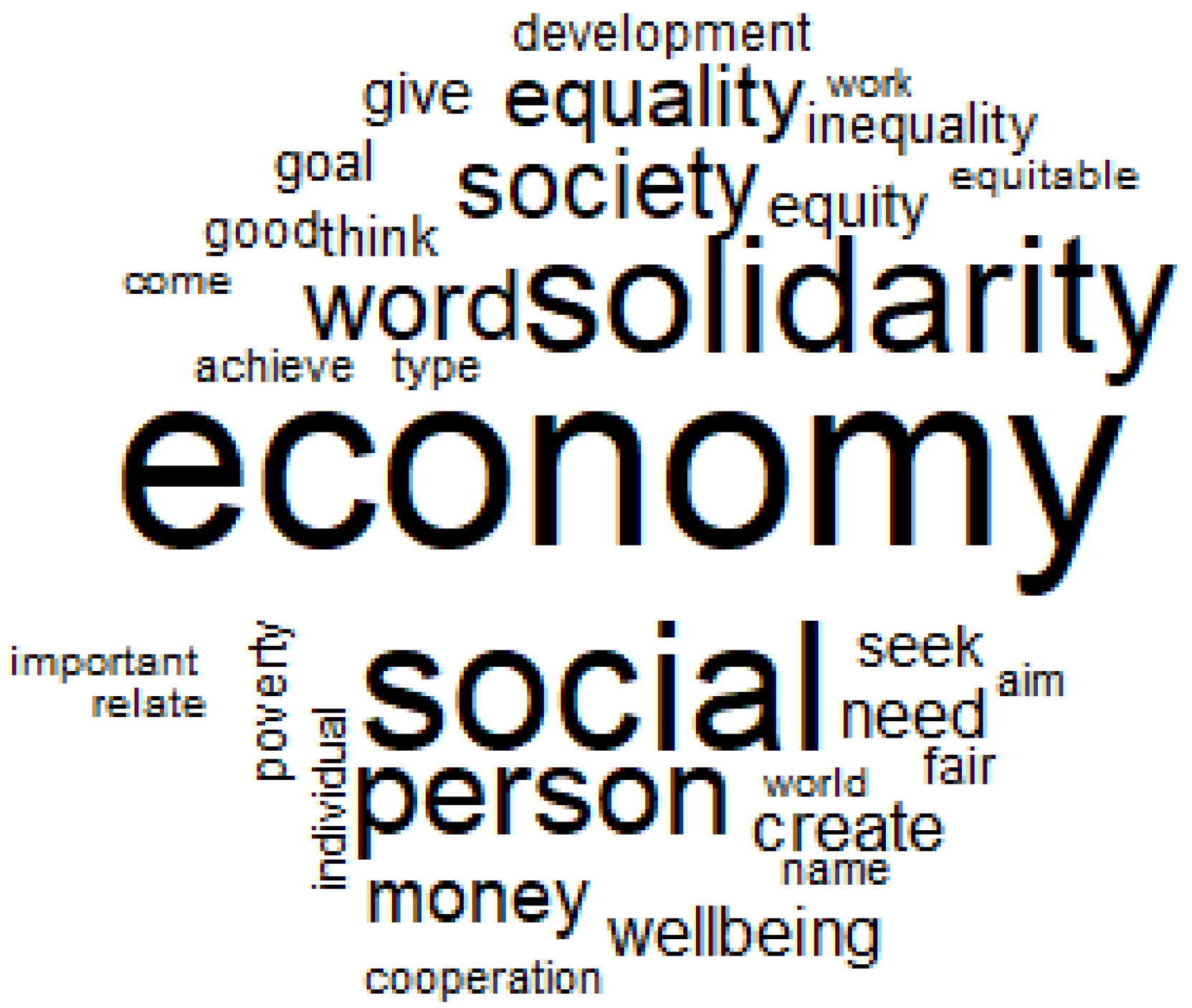

5.1.1. Word Cloud

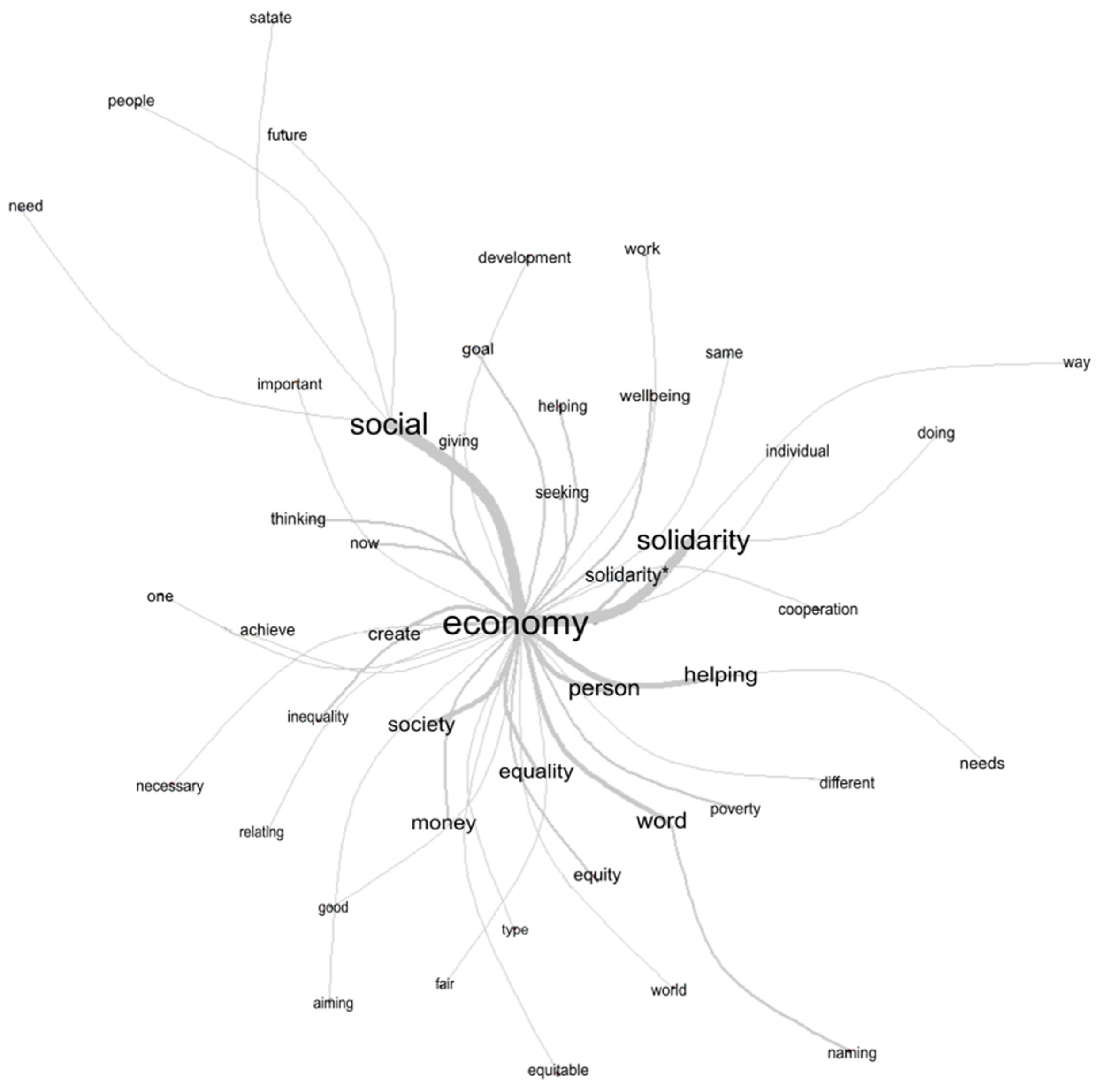

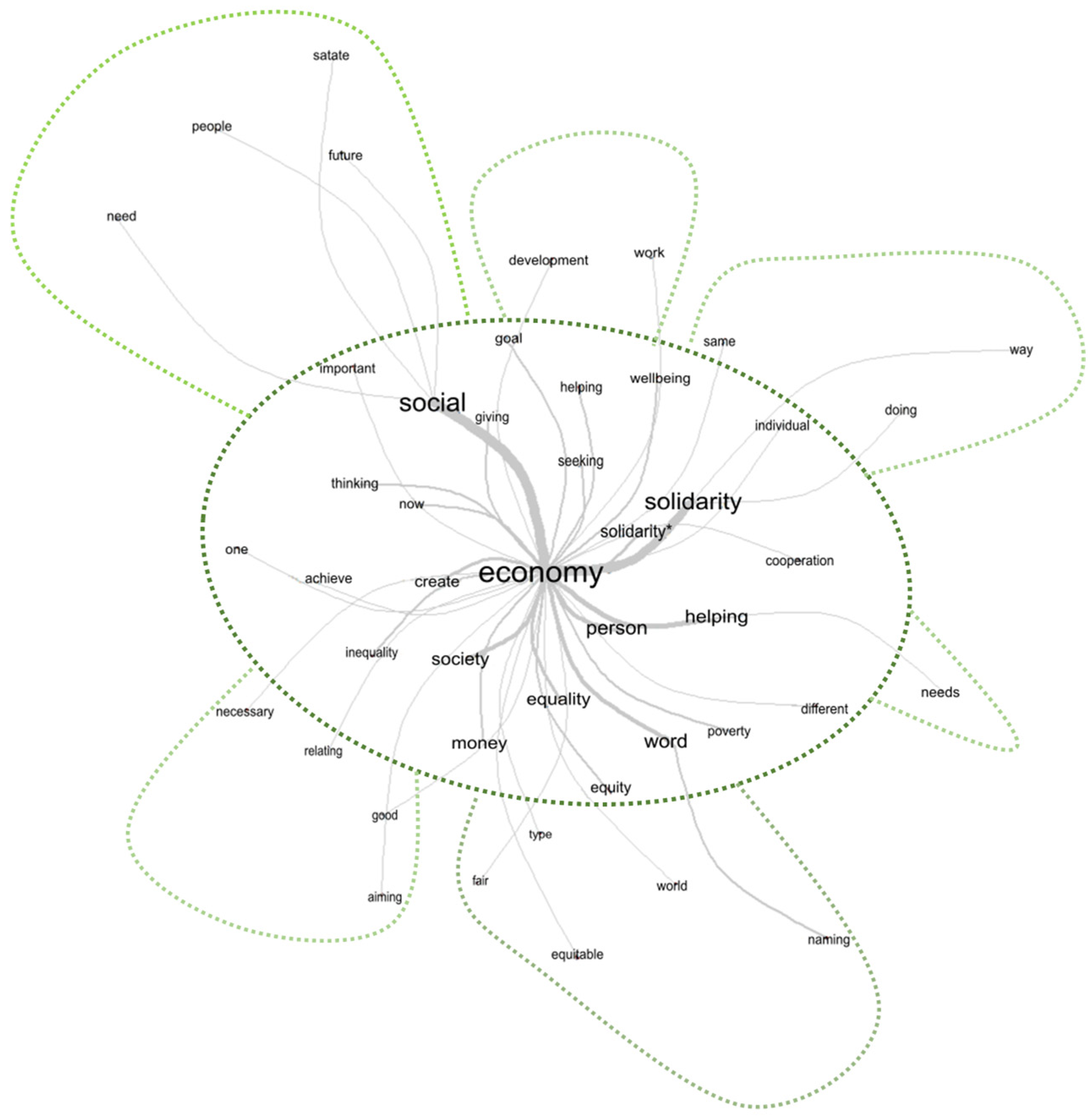

5.1.2. Similarity Analysis

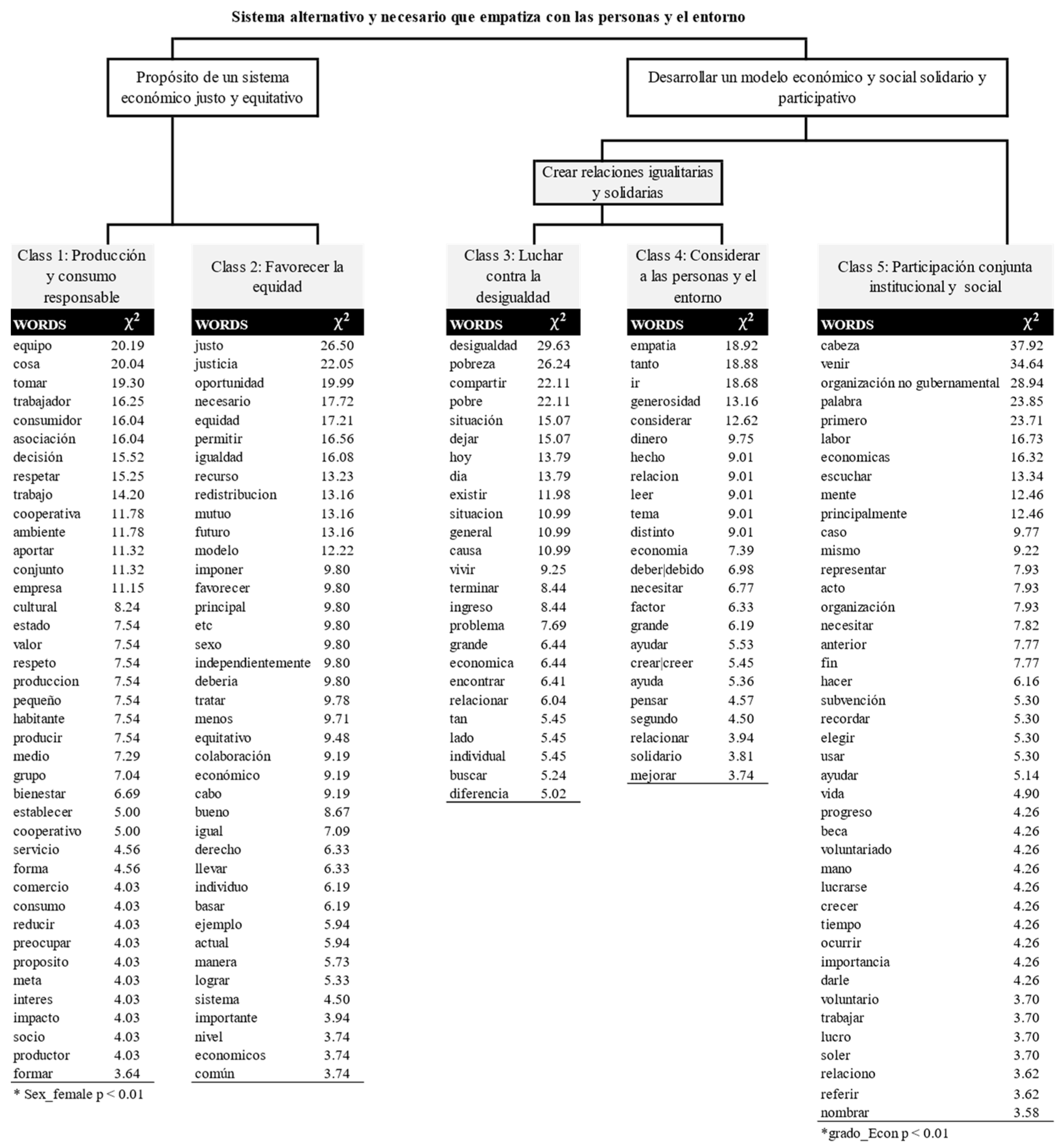

5.1.3. Reinert Method

“The Solidarity Economy proposes a transition towards new models in which equity is a central element of relationships among individuals, communities and peoples, as well as the planet.”[E87, woman, BAM degree. χ2 = 210.8]

“I think the aim of the SSE is to achieve social development, responding to the problems that exist today and reducing the inequalities that exist.”[E119, women, economics degree. χ2 = 196.2]

“The SSE creates decent jobs.”[E86, woman, business administration and management (BAM) degree. χ2 = 154.6]

“The creation of enterprises such as cooperatives that break away from the classic hierarchical model base their ideas on the SSE.”[E146, man, economics degree. χ2 = 199.2]

“I consider that the SSE should aim to improve society in general… these improvements would be in the environment, the region’s economy and the economy of the different stages of production (farmer, processors, wholesaler).”[E48, woman, BAM degree. χ2 = 199.2]

“In an equitable economic system, it is sought to ensure that all people have access to the resources necessary to satisfy their basic needs (…). This involves a fair distribution of wealth and income, as well as an equality of opportunities…”[E54, man, business degree. χ2 = 164.1]

“Companies that are set up based on this economic model (SSE) are usually founded on the principle of mutual support among peers. (…) The model is concerned with inequalities and an optimistic vision of a fairer future”[E147, man, economics degree. χ2 = 200.3]

“Since solidarity involves empathy with and support for society, it will therefore help to achieve an SSE.”[E23, woman, business degree. χ2 = 68.5]

“(…) I think that a social economy, as the name indicates, must be based on cooperation among the people and different organisations that constitute the system.”[E155, woman, economics degree. χ2 = 196.8]

“In order to set in motion an economy that is more social and caring it is necessary to act as a community, seeking the common good, and not the interests of the individual.”[E80, woman, BAM degree. χ2 = 156.8]

“The authorities and the government can establish policies that favour the reduction of income and social inequalities, such as through laws or setting different kinds of taxes.”[E170, woman, economics degree. χ2 = 167.2]

6. Discussion and Final Reflections

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alexander, P. A., & Murphy, P. K. (1998). The research base for APA’s learner-centered psychological principles. In N. Lambert, & B. McCombs (Eds.), Issues in school reform: A sampler of psychological perspectives on learner-centered schools (pp. 33–60). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Amiano, M. I. (2019). La responsabilidad social universitaria desde la perspectiva de la pertinencia social: Mecanismos de interlocución con la sociedad en el caso de las universidades españolas [Ph.D. Thesis, Hegoa, UPV/EHU]. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/706632239/TESIS-AMIANO-BONATXEA-MARIA-IRATXE (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Andersen, L. L., Hulgård, L., & Laville, J. L. (2022). The Social and Solidarity Economy: Roots and Horizons. In L. L. Langergaard (Ed.), New economies for sustainability. Ethical economy (Vol. 59). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos-Alonso, A., & Garcia-Azpuru, A. (2021). Diferentes propuestas para el despliegue de la economía social y solidaria: Ecosistemas, sistemas, mercados sociales, circuitos solidarios y redes solidarias. GIZAEKOA—Revista Vasca De Economía Social, 1(18). Available online: https://ojs.ehu.eus/index.php/gezki/article/view/22880 (accessed on 2 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Arcos-Alonso, A., & Olea, M. J. (2020). Enseñar y aprender otra economía en clave crítica: Economía social y solidaria a través del aprendizaje servicio crítico. In Educación para el Bien Común: Hacia una práctica crítica, inclusiva y comprometida socialmente responsable. Octaedro. [Google Scholar]

- Arcos-Alonso, A., Elías-Ortega, Á., & Arcos Alonso, A. (2020). Intergenerational service-learning, sustainability, and university social responsibility: A pilot study. Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences, 15(6), 1629–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos-Alonso, A., Las Heras, J., Fernandez de la Cuadra-Liesa, I., & Garcia-Azpuru, A. (2023). Identificación y análisis de representaciones sobre economía social y solidaria como herramienta de transversalización de valores sociales en la educación universitaria de empresa. In Caminando hacía la innovación en educación: De la teoría a la práctica (pp. 15–37). Dykinson. [Google Scholar]

- Bakaikoa Azurmendi, B., & Morandeira Arca, J. (2012). El cooperativismo vasco y las políticas públicas. Ekonomiaz: Revista vasca de economía, 1(79), 234–263. [Google Scholar]

- Bohm, I. (2023). Cultural sustainability: A hidden curriculum in Swedish home economics? Food, Culture & Society, 26(3), 742–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzaga, C., Salvatori, G., & Bodini, R. (2019). Social and solidarity economy and the future of work. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Emerging Economies, 5(1), 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. (2008). El sentido práctico. Siglo XXI de España Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Bretos, I., Diaz-Foncea, M., & Marcuello, C. (2023). Economía social, estudios críticos de gestión y universidad: Un estudio de caso del laboratorio de economía social. CIRIEC-España revista de economía pública social y cooperativa, 129–158. Available online: https://turia.uv.es/index.php/ciriecespana/article/view/22979 (accessed on 2 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Brod, G. (2021). Toward an understanding of when prior knowledge helps or hinders learning. NPJ Science of Learning, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camargo, B. V., & Justo, A. M. (2013). IRAMUTEQ: Um software gratuito para análise de dados textuais. Temas em Psicologia, 21(2), 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, B., & Ramey, E. A. (2014). Pluralism at work: Alumni assess an economics education. International Review of Economics Education, 16, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coraggio, J. L. (2014). La Economía Social y Solidaria: El papel de las universidades [Ponencia]. Seminario Universidad pública y economías solidarias, Seminario de ESS y Popular. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A. P., Reis, L. P., Moreira, A., Longo, L., & Bryda, G. (Eds.). (2021). Computer supported qualitative research: New trends in qualitative research (WCQR2021) (Vol. 1345). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle, D. (2011). The economics of enough: How to run the economy as if the future matters. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dacheux, E., & Goujon, D. (2011). The solidarity economy: An alternative development strategy? International Social Science Journal, 62, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. (2006). Defining social enterprise. Social Enterprise: At the Crossroads of Market, Public Policies and Civil Society, 7, 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Denis, A. (2009). Pluralism in economics education. International Review of Economics Education, 8(2), 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Foncea, M. ((Coord.)). (2023). La formación universitaria en economía social en España. Informe 2023. CIRIEC España. [Google Scholar]

- Eiguren, A., Idoiaga-Mondragon, N., Berasategi, N., & Picaza, M. (2021). Exploring the social and emotional representations used by the elderly to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 586560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Kassar, A.-N., Makki, D., Gonzalez-Perez, M. A., & Cathro, V. (2023). Doing well by doing good: Why is investing in university social responsibility a good business for higher education institutions cross culturally? Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 30(1), 142–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Ruiz, D., Guzmán-Alfonso, C., & Barroso-González, M. d. l. O. (2016). La formación en economía social. Análisis de la oferta universitaria de pos-grado en España. REVESCO, Revista de Estudios Cooperativos, 121, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontecoba, A., Silva, J. R., & Soteras, M. L. (2015). Desafíos para la enseñanza de la Economía Social y Solidaria. Algunas reflexiones desde la experiencia universitaria. In La Economía Social y Solidaria en la Historia de América Latina y el Caribe (p. 203). IDELCOOP-Instituto de la Cooperación-Fundación de Educación, Investigación y Asistencia Técnica. [Google Scholar]

- Franco-Martinez, J. A., & Garcia-Gordillo, M. A. (2020). Heterodox economy in the neoliberal education age. Social Sciences, 9(5), 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P., Flecha, R., & Freire, A. M. A. (1997). A la sombra de este árbol. El Roure. [Google Scholar]

- Fullbrook, E. (Ed.). (2007). Real world economics. Anthem Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaete, R. (2011). La responsabilidad social universitaria como desafío para la gestión estratégica de la Educación Superior: El caso de España. Revista de educación, 5(355), 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaete, R. (2018). Conciliación trabajo-familia y responsabilidad social universitaria: Experiencias de mujeres en cargos directivos en universidades chilenas. Revista Digital de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria, 12(1), 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gérard, M., & Vandenberghe, V. (2007). Introduction: Economics of higher education. Education Economics, 15(4), 383–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M. E., Hernández, I., & García, S. (2019). Educación superior y economía solidaria hacia un enfoque territorial. Sophia, 15(1), 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, G., & Harman, K. (2008). Strategic mergers of strong institutions to enhance competitive advantage. Higher Education Policy, 21(1), 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvold-Kvangraven, I., & Alves, C. (2020). ¿Por qué tan hostil? Quebrando mitos sobre la economía heterodoxa. Ensayos de Economía, 30(56), 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattan, C., Alexander, P. A., & Lupo, S. M. (2024). Leveraging what students know to make sense of texts: What the research says about prior knowledge activation. Review of Educational Research, 94(1), 73–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J., & Jacob, W. (2010). Series Editors’ Introduction. In V. Rust, L. Portnoi, & S. Bagley (Eds.), Higher education, policy, and the global competition phenomenon. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Arteaga, I., Muñoz, C. P., & Castañeda, S. R. (2018). Intereses y perspectivas formativas en economía social y solidaria de los estudiantes universitarios. CIRIEC-España, 94, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, J. (2008). World class universities. Higher Education Policy, 21(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iafrancesco, G. (2004). Currículo y plan de estudios. Editorial magisterio. [Google Scholar]

- Idoiaga, N., Beloki, N., Yarritu, I., Zarrazquin, I., & Artano, K. (2023). Active methodologies in Higher Education: Reasons to use them (or not) from the voices of faculty teaching staff. Higher Education, 88(3), 919–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idoiaga-Mondragon, N., Berasategi Sancho, N., Eiguren Munitis, A., & Dosil Santamaria, M. (2021). Exploring the social and emotional representations used by students from the University of the Basque Country to face the first outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic. Health Education Research, 36(2), 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idoiaga-Mondragon, N., Berasategi Sancho, N., Eiguren Munitis, A., & Picaza, M. (2020). Exploring children’s social and emotional representations of the COVID-19 pandemic. Froniers in Psychology, 11, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idoiaga-Mondragon, N., Gil de Montes, L., & Valencia, J. (2017). Understanding an ebola outbreak: Social representations of emerging infectious diseases. Journal of Health Psychology, 22(7), 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Student Initiative for Pluralism in Economics. (2014). Llamamiento internacional de estudiantes de economía a favor de una enseñanza pluralista. Revista de Economía Institucional, 16(30), 339–341. [Google Scholar]

- Iramuteq. (2023). Iramuteq. Available online: http://iramuteq.org/ (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Jackson, P. W. (1990). Life in classrooms. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby, B. (1996). Service-learning in higher education: Concepts and practices. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Joffe, H., & Elsey, J. W. B. (2014). Free association in psychology and the grid elaboration method. Review of General Psychology, 18(3), 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliá, J. F., & Díaz-Foncea, M. (2021). Universidad y Economía Social: Un binomio necesario para una economía con valores. In La Economía Social y el Cooperativismo en las modernas economías de mercado: En homenaje al profesor José Luis Monzón Campos (pp. 77–90). Tirant lo Blanch. [Google Scholar]

- Juliá, J. F., Meliá, E., & Miranda, E. (2020). Rol de la Economía Social y la universidad en orden a un emprendimiento basado en el conocimiento tecnológico y los valores. CIRIEC-España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa, 98, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaivola, T., & Rohweder, L. (2007). Towards sustainable development in higher education-reflections. Ministerio de Educación Finés. [Google Scholar]

- Kallo, J., & Välimaa, J. (2024). Higher education in nordic countries: Analyzing the construction of policy futures. Higher Education, 1–18. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10734-024-01280-4 (accessed on 23 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Khoo, S. M. (2016). Public Scholarship and Alternative Economies: Revisiting Democracy and Justice in Higher Education Imaginaries. In L. Shultz, & M. Viczko (Eds.), Assembling and governing the higher education institution (pp. 149–174). Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J. E. (2013). A case for pluralism in economics. The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 24(1), 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintzer, F. C. (1999). Articulation and transfer: A symbiotic relationship with lifelong learning. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 18(3), 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, O., & Licata, L. (2003). When group representations serve social change: The speeches of Patrice Lumumba during the Congolese decolonization. British Journal of Social Psychology, 42(4), 571–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larrán-Jorge, M., & Andrades-Peña, F.-J. (2015). Análisis de la responsabilidad social universitaria desde diferentes enfoques teóricos. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación Superior, 6(15), 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, M. (2005). ¿Cuáles son las características de las prácticas pedagógicas de profesores chilenos en ejercicio? (What are the characteristics of the pedagogical practices of practicing Chilean teachers?). Revista Digital PREAL, 1–20. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/288153019/cuales-Son-Las-Caracteristicas-de-Las-Practicas-Pedagogicas-de-Profesores-Chilenos-en-Ejercicio (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Laville, J. L. (2009). Supporting the social and solidarity economy in the European Union. In A. Amin (Ed.), The social economy. International perspectives on economic solidarity (pp. 232–252). Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Laville, J. L., & Nyssens, M. (2001). The social enterprise: Towards a theoretical socio-economic approach. In C. Borzaga, & J. Defourny (Eds.), The emergence of social enterprise (1st ed., pp. 324–344). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Monaco, G., & Bonetto, E. (2019). Social representations and culture in food studies. Food Research International, 115, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, P., & Ratinaud, P. (2012). L’analyse de similitude appliquée aux corpus textuels: Les primaires socialistes pour l’élection présidentielle française (septembre-octobre 2011). Actes des 11eme Journées Internationales d’Analyse Statistique des Données Textuelles. JADT, 2012, 687–699. [Google Scholar]

- Marginson, S. (2023). Student self-formation: An emerging paradigm in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 49(4), 748–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mearman, A., Wakeley, T., Shoib, G., & Webber, D. (2011). Does pluralism in economics education make better educated, Happier students? A qualitative analysis. International Review of Economics Education, 10(2), 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meira, D., Bernardino, S., & Martinho, A. L. (2020). Um Contributo Inovador para o Ensino da Economia Social em Portugal: O caso do Mestrado em Gestão e Regime Jurídico-empresarial da Economia Social. In C. Pérez Muñoz, & I. Hernández Arteaga (Eds.), Economía social y solidaria en la educación superior: Un espacio para la innovación (tomo 3) (pp. 149–180). Ediciones Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendy, G., Chiroque, H., & Recalde, E. (2015). Construcción de espacios institucionales en economía social y solidaria desde el ámbito universitario: El caso del proyecto CREES de la Universidad Nacional de Quilmes-Argentina. Praxis Social, Revista de Trabajo Social, 6(3), 125–151. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, E. (2010). Solidarity economy: Key concepts and issues. In E. Kawano, T. Masterson, & J. Teller-Ellsberg (Eds.), Solidarity economy I: Building alternatives for people and planet (pp. 25–41). Center for Popular Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Molero-Simarro, R. (2016). Corrientes heterodoxas de pensamiento económico. In F. García, & A. Ruíz (Coord.), Hacia una economía más justa. Una introducción a la economía crítica. Economistas Sin Fronteras. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Neira, J. (2017). Tutorial para el análisis de textos con el software IRAMUTEQ. Universidad de Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Montoya, L. (2017). Experiencias de vinculación de universidades públicas con organizaciones y movimientos de economía social y solidaria de Argentina y Perú. Revista Economía, 69(109), 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J. N., & Martínez, F. C. (2016). Modelos de responsabilidad social universitaria y principales desafíos para su implementación en facultades de negocios. Capic Review, 14, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, N. V., & Moolakkattu, J. S. (2022). Solidarity Economy and Social Change: Contesting Liberal Universalism. In R. Baikady, S. Sajid, V. Nadesan, J. Przeperski, M. R. Islam, & J. Gao (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of global social change. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, R. (2015). Las universidades públicas argentinas y la Economía Social y Solidaria. Hacia una educación democrática y emancipadora. Revista + E Versión Digital, 5, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pastore, R., & Altschuler, B. (2015). Diálogo de saberes y formación universitaria integral para el desarrollo de la Economía Social y Solidaria (ESS): Reflexiones desde una experiencia universitaria. AUTOGESTÃO: Economía dos Trabalhadores & Educação Popular (ET & EP), 1(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez de Mendiguren, J. C., & Etxezarreta, E. (2015). Sobre el concepto de economía social y solidaria: Aproximaciones desde Europa y América Latina. Revista de Economía Mundial, 40, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Suárez, M., & Sánchez-Torné, I. (2022). University assessment of collaborative learning in social economic. Human review. International Humanities Review/Revista Internacional De Humanidades, 12(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanyi, K. (1944). The great transformation. Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, M. (2004). Does active learning work? A review of the Research. Journal of Engineering Education, 93(3), 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puin, M. E., Hernandez-Arteaga, I., & Simanca, F. A. (2021). Percepciones de los docentes universitarios para la construcción de una cultura de paz. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação, Rio de Janeiro, 29, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, J. (2020). Improving pluralism in economics education. In Contemporary issues in heterodox economics (pp. 282–298). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Reinert, M. (1996). Alceste (Version 3.0). Images.

- Rossouw, N., & Frick, L. (2023). A conceptual framework for uncovering the hidden curriculum in private higher education. Cogent Education, 10(1), 2191409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Bueno, A. (2017). Trabajar con IRAMUTEQ: Pautas. Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Trabajar-con-Iramuteq%3A-Pautas-Bueno/7699fb2375af79de9e02523c9d1597916f6e861b (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Ruiz-Corbella, M., & Bautista-Cerro, M. (2016). La responsabilidad social en la universidad española. Teoría de la educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 28(1), 159–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, D., & Watters, J. (2006). The corporatisation of higher education: A question of balance. In I. Vardi, & A. Bunker (Eds.), Critical visions: Thinking, learning and researching in higher education: Proceedings of HERDSA (CD Rom) (pp. 316–323). HERDSA. [Google Scholar]

- Santana-Vega, L. E., Suárez-Perdomo, A., & Feliciano-García, L. (2020). El aprendizaje basado en la investigación en el contexto universitario: Una revisión sistemática | Inquiry-based learning in the university context: A systematic review. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 78(277), 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T., & Horng, C. Y. (2023). Exploratory study about achievements and issues of university social responsibility—“USR” as a dynamic process. International Journal of Educational Development, 102, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonhardt-Bailey, C. (2013). Deliberating American monetary policy. A textual analysis. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer-Krah, E., & Engartner, T. (2019). Students’ perception of the pluralism debate in economics: Evidence from a quantitative survey among German universities. International Review of Economics Education, 30, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sent, M. -E. (2006). Pluralisms in economics. In S. H. Kellert, H. E. Longino, & C. K. Waters (Eds.), Scientific pluralism (pp. 80–98). University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shore, C., & Wright, S. (2017). Death of the public university: Uncertain futures for higher education in the knowledge economy. Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter, S., & Rhoades, G. (2004). Academic capitalism and the new economy. Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sonu, D., & Marri, A. R. (2018). The hidden curriculum in financial literacy: Economics, standards, and the teaching of young children. Cuny Academic Works, 7–26. Available online: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_pubs/413/ (accessed on 24 March 2024).

- Söderbaum, P. (2004). Economics as ideology and the need for pluralism. In E. Fullbrook (Ed.), A guide to what’s wrong with economics (pp. 158–168). Athem Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stilwell, F. (2006). Four reasons for pluralism in the teaching of economics. Australasian Journal of Economics Education, 3(1), 42–55. [Google Scholar]

- UN Inter-Agency Task Force on Social and Solidarity Economy-UNRISD. (2014). Social and solidarity economy and the challenge of sustainable development. Available online: https://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/3051197/1/Position-Paper_TFSSE_Eng1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- UN Inter-Agency Task Force on Social and Solidarity Economy-UNRISD. (2024). Promoting the social and solidarity economy for sustainable development. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/4063386?v=pdf (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Urdapilleta, J. (2019). Fortalecimiento de la responsabilidad social universitaria desde la perspectiva de la economía social y solidaria. Perfiles Educativos, 41(164), 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utting, P. (2015). The challenge of scaling up Social and Solidarity Economy. In P. Utting (Ed.), Social and solidarity economy: Beyond the fringe (pp. 1–37). Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Utting, P. (2023). Contemporary Understandings of the Social and Solidarity Economy. In E. I. Yi (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the social and solidarity economy (pp. 19–26). Edward Elgar Publishing. Available online: https://www.elgaronline.com/display/book/9781803920924/9781803920924.xml (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Vallaeys, F. (2008). ¿Qué es la responsabilidad social universitaria? Available online: https://www.ausjal.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Que-es-la-Responsabilidad-Social-Universitaria.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Vallaeys, F. (2014). La responsabilidad social universitaria: Un nuevo modelo universitario contra la mercantilización. RIES Revista Iberoamericana de Educación Superior, 5(12), 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kesteren, M. T. R., Krabbendam, L., & Meeter, M. (2018). Integrating educational knowledge: Reactivation of prior knowledge during educational learning enhances memory integration. NPJ Science Learn, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Vught, F. (2008). Mission diversity and reputation in higher education. Higher Education Policy, 21(2), 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Melgarejo, L. M. (1994). Sobre el concepto de percepción. Alteridades, 4(8), 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Vasco, G. (2023). Estadística de la Economía Social 2022 y Avance 2023. Departamento de Trabajo y Empleo, Gobierno Vasco. [Google Scholar]

- Villancourt, Y. (2013). La economía social en la co-producción y la co-construcción de las políticas públicas [Ph.D. dissertation, Facultad de Ciencias Económicas, Universidad de Buenos Aires]. [Google Scholar]

- Wigmore-Álvarez, A., Ruiz-Lozano, M., & Fernández-Fernández, J. L. (2020). Management of university social responsibility in business schools. An exploratory study. The International Journal of Management Education, 18(2), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharia, R. M., Stancu, A., & Diaconu, M. (2010). University social responsibility and stakeholders’ influence. Transformations in Business & Economics, 9(19), 434–447. [Google Scholar]

- Zajda, J., & Rust, V. (2016). Current Research Trends in Globalisation and Neo-liberalism in Higher Education. In J. Zajda, & V. Rust (Eds.), Globalisation and higher education reforms. globalisation, comparative education and policy research (Vol. 15). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | Man | Woman | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Average age: 22.8 years] | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Economics degree | 76 | 42% | 34 | 44.7% | 42 | 55.3% |

| Business degree | 44 | 24% | 15 | 34.1% | 29 | 65.9% |

| BAM degree | 63 | 34% | 22 | 34.9% | 41 | 65.1% |

| Total | 183 | 71 | 39% | 112 | 61% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arcos-Alonso, A.; Fernandez de la Cuadra-Liesa, I.; Garcia-Azpuru, A.; Barba Del Horno, M. Rethinking Economics Education: Student Perceptions of the Social and Solidarity Economy in Higher Education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15010027

Arcos-Alonso A, Fernandez de la Cuadra-Liesa I, Garcia-Azpuru A, Barba Del Horno M. Rethinking Economics Education: Student Perceptions of the Social and Solidarity Economy in Higher Education. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleArcos-Alonso, Asier, Itsaso Fernandez de la Cuadra-Liesa, Amaia Garcia-Azpuru, and Mikel Barba Del Horno. 2025. "Rethinking Economics Education: Student Perceptions of the Social and Solidarity Economy in Higher Education" Education Sciences 15, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15010027

APA StyleArcos-Alonso, A., Fernandez de la Cuadra-Liesa, I., Garcia-Azpuru, A., & Barba Del Horno, M. (2025). Rethinking Economics Education: Student Perceptions of the Social and Solidarity Economy in Higher Education. Education Sciences, 15(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15010027