Abstract

Academic misconduct is ubiquitous, a fortiori during crisis periods. The present research examines undergraduates’ learning motivation, based on Self-Determination Theory and personality traits factors, according to the Big Five Factor Model, affecting academic misconduct across different time spans: Before, during, and after a life-changing event. Using online questionnaires, we measured the level of academic misconduct, learning motivation, and personality traits of 1090 social sciences students during five different time spans pre-COVID-19, during COVID-19 (before and after vaccination), and after COVID-19 (post and long post). The results showed significant differences in students’ self-reported academic misconduct levels among the different periods and similar misconduct levels in pre-COVID-19 and long post-COVID-19. Additionally, the findings exhibited that external motivation significantly increases academic misconduct and that two out of five personality traits (agreeableness and emotional stability) reduce their occurrences. We conclude that higher education preparedness for academic integrity during an emergency is still a desideratum and that ethical concerns should not be abandoned but rather be fully addressed during emergency periods. This could be addressed by instructors allocating tasks during emergency groups involving students with pro-social personalities (agreeableness and emotional stability) and intrinsic motivation to serve as social agents in deterring academic misconduct.

1. Introduction

Since their inception, computers have revolutionised education [1], reshaping educational practices through the advancement of information and communication technology as well as online education [2]. Traditional face-to-face teaching integrated digital or hybrid educational systems [3], a transition further accelerated by the unexpected pandemic, i.e., COVID-19 [4], forcing mandatory online instruction [5], sometimes termed emergency remote teaching (ERT) [6,7]. This phenomenon affected academic integrity across [8] all education disciplines [9], presenting new challenges to the educational experience [10], demanding adaptability skills [2] and coping strategies [11].

Higher education prepares students for their future [12] and develops graduates who are not only highly skilled and technically proficient but also embody honesty, ethical responsibility, and a strong commitment to serving their profession and society [13]. An added value to education is desired conduct [14,15], such as academic integrity [11]. Traditionally, evaluating academic integrity has been limited to assessing student conduct. However, it is becoming clear that a more contemporary approach going beyond academic integrity breaching is necessary [16].

Academic integrity for researchers covers research ethics, data presentation, and authorship. For students, it involves plagiarism, cheating, or bribing for grades [17]. Previous research on academic integrity among students has focused on four main areas: prevalence, severity, causes, and solutions [18]. Students’ academic integrity breaches, like academic misconduct or dishonest academic behaviour, incite posterior counterproductive or fraudulent behaviours [19], are ubiquitous [20] and widespread, and have, unfortunately, become normalised globally [21].

The probability of future worldwide closures due to natural incidents such as floods, tsunamis, wildfires, or human situational incidents—including war, terror attacks, or shootings—may lead educational institutes to new challenges [22]. Thus, it is a desideratum to unveil the impacts of emergencies on learning and teaching [2] and the post-crisis trend and its long-lasting impact [23]. Despite the myriad research on academic dishonesty [24], to the best of our knowledge, the literature has not inquired into undergraduates’ motivation and personality traits factors that have influenced academic dishonesty before, during, and in the aftermath of COVID-19. The present research aims to analyse the relationship among the above variables and provide new insights into the research literature and practice.

The probability of future worldwide closures due to natural incidents such as floods, tsunamis, wildfires, or human situational incidents- including war, terror attacks, or shootings—may lead educational institutes to new challenges [22]. Thus, it is a desideratum to unveil the impacts of emergencies on learning and teaching [2] and the post-crisis trend and its long-lasting impact [23]. Despite the myriad research on academic dishonesty [24], to the best of our knowledge, the literature did not inquire into the undergraduates’ motivation and personality traits factors influencing academic dishonesty before, during, and in the aftermath of COVID-19. The present research aims to analyse the relationship among the above variables and provide new insights into the research literature and practice.

2. Theoretical Background

Events like natural disasters or global health pandemics have affected how academic content is delivered in higher education [25] and studying habits [26]. Thus, the COVID-19 pandemic introduced unprecedented uncertainties into the global education system [27]. Moreover, it hastened the establishment of online learning delivery platforms [28]. In other words, the global COVID-19 pandemic has compelled higher education institutions to transition from in-person instruction to emergency remote teaching (ERT), sparking heightened concerns about academic integrity [29].

Academic integrity is a transdisciplinary field of research, nuanced and complex [30]. It entails behaviours characterised by trustworthiness, respectfulness, fairness, and responsibility [31]. Defined as “compliance with ethical and professional principles, standards, practices and consistent system of values, that serves as guidance for making decisions and taking actions in education, research and scholarship” [32], it means following ethical standards in education and research [18].

Breaching or violating those principles in higher education is regarded as academic misconduct [8], fraudulent behaviour [18], or academic dishonesty [33,34] and is detrimental to the learning process [35]. A vast majority of post-secondary students admitted engaging in some form of academic misconduct [36]. Research suggests that academic misconduct, such as plagiarism, is more common among younger males who are poorly motivated and procrastinators [37], although other findings show that female misconduct rates are now comparable [38].

The rise of online education has led to an increase in academic dishonesty [39]. The literature has examined multiple factors that elucidate the concept of academic dishonesty [40]. Students commit academic dishonesty for various reasons [37]. Some factors contributing to academic dishonesty include stress and pressure, peer misbehaviour, insufficient knowledge [39], lack of motivation, and procrastination [37], to mention some. Nonetheless, there is no consensus regarding its primary causes.

Certain scholars have demonstrated that various factors influence academic misconduct, such as motivational research [41,42] or personality [38,40]. Motivation to learn involves improving an individual’s learning behaviours, directing their learning goals, and maintaining their educational engagement [43]. Motivational psychology highlights that an individual’s drive to pursue a specific objective is influenced by both personal traits and situational contexts [44,45]. Nonetheless, others proposed through their accentuation hypothesis that personal attributes become more pronounced when external factors (like COVID-19) disrupt established social balances [45,46].

The five-factor model (FFM) of personality traits is the most influential and widely used personality theory [47]. According to trait activation theory, there are situations that can potentially trigger behaviours [48]. In other words, research studies have emphasised the role of contextual factors [49] like COVID-19. Changes in the academic and social lives of university students, such as those caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, can highlight the role of their characteristics in dealing with these circumstances. These personal traits play a pivotal role in students’ capacity to adapt to such life-altering circumstances [45].

COVID-19 has dramatically transformed higher education worldwide, affecting learning, teaching methods, assessment strategies, the experiences of students and academics, the learning environment, and policymaking in higher education [50]. Nonetheless, the literature on education in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic is still evolving [51], including a plethora of subjects, including pedagogic practices in online learning environments [25]. The learning environment and teacher–student interactions also play crucial roles in shaping student motivation [52]. Traditional learning environments include face-to-face (F2F) and planned online learning (POE), with special emphasis on instructors’ readiness [53]. Student performance in POE is often lower than in F2F settings [54].

Despite digital technology’s potential for teaching and learning [27], like the widespread automatic paraphrasing tools [55] and artificial intelligence [55,56], there is still a need to unveil digital-integrity behaviour [57]. It is imperative to understand dishonest behaviour to foster the academic and professional growth of undergraduates [58] and enhance positive strategies for academic integrity [59] and policies [60]. Thus, considering potential future disruptions [22], whether from human situational incidents or natural disasters, coping skills become paramount [29].

Studying the motivations behind academic dishonesty behaviours could provide insights into understanding these actions better [61]. Thus, based on Self-Determination Theory (SDT) [62] and expanding on previous research [63], the present research aims to fill the literature gap on the aftermath of an unexpected event (COVID-19) in higher education settings and its influence on academic dishonesty. Self-Determination Theory is a widely studied perspective on human motivation, defining it as the underlying reason for behaviour [64], as people’s actions are influenced by their motives, needs, and incentives [65]. This theory posits that there are three essential needs for well-being: autonomy (control and choice), competence (skill and effectiveness), and relatedness (connection and belonging) [66]. Autonomy involves being in control of one’s actions and having the freedom to make choices. Competence refers to the feeling of being effective and skilled in one’s activities. Relatedness is about feeling connected and belonging to others and a community [65]. Our research question is as follows: How do individual characteristics (motivation and personality traits) influence academic dishonesty according to contextual factors (before, during, and in the aftermath of COVID-19)?

2.1. Individual Characteristics

2.1.1. Learning Motivation

Motivation triggers and sustains one’s actions toward a goal, making it among the most significant factors impacting students’ learning achievements [67] and playing a crucial role in students’ learning [68]. Developing strong study habits is essential for boosting learning [26]. The Self-Determination and Intrinsic Motivation Theories [62] are a broad theory of human motivation, encompassing various types of motivation guiding human behaviours [67]. It posits three forms of academic motivational regulations based on distinct underlying reasons or goals for an individual’s actions: intrinsic, extrinsic and amotivation. Intrinsic motivation stems from engaging in an activity because of its inherent enjoyment or interest rather than external factors. Conversely, extrinsic motivation arises from pursuing an activity for external, separable outcomes [40,69]. Amotivation indicates the degree to which a person lacks the motivation to engage in specific activities or exhibits behaviour lacking intentionality [67,69,70].

Education entails recognising the factors that impact students’ learning motivation and evaluating strategies to enhance it [71]. Furthermore, in an educational setting, students’ psychological attitudes significantly influence their learning outcomes. Higher levels of enthusiasm enhance their engagement, thus improving their ability to absorb and retain knowledge. Conversely, a lack of academic dedication can hinder the attainment of optimal academic results [43]. Learning motivation, either intrinsic or extrinsic, influences the learning process and determines students learning (mis)behaviour [72].

For example, extrinsic motivation in learning occurs when the learner lacks interest in the subject itself and focuses solely on the rewards or benefits they receive [73]. Put differently, the types of motivational orientation have varying academic outcomes [61]. For example, individuals lacking motivation are more likely to engage in academic dishonesty [74,75]. Furthermore, previous studies showed that individuals influenced by external motivation are more prone to academic misconduct [75,76]. Thus, based on the above, we posit the following:

H1.

External learning motivation increases academic misconduct.

2.1.2. Personality Traits

Personality traits represent stable patterns of individual behaviours, feelings, and thoughts manifest in interacting with an environment [77]. The five-factor model, or FFM, is the widely used model of personality traits [78]. The FFM classifies individual personality into five main dimensions: Openness to experience—reflects levels of intellectual curiosity, creativity, and preference for diversity and innovation; Conscientiousness—represents tendencies towards self-discipline, responsibility, and goal attainment; Extraversion—encompasses traits of energy, positivity, assertiveness, sociability, and talkativeness.; Agreeableness—indicates a predisposition towards compassion, cooperation, and trust, as opposed to suspicion and hostility; and neuroticism (or emotional stability)—indicates the likelihood of experiencing negative emotions like anger, anxiety, depression, or vulnerability.

Some meta-analyses [79] examined the extent of personality traits and performance and found that three of the Big Five personality traits—conscientiousness, openness, and agreeableness—are significantly associated with positive academic behaviour. Prior research conducted before the pandemic regarding the tendency to engage in academic misconduct provided insights into the relationships between students’ characteristics and their propensity to misbehave [8]. For example, Giluk and Postlethwaite [80] found that conscientiousness and agreeableness are negatively related to cheating. Adeniyi’s [13] research revealed that neuroticism significantly prompted academic dishonesty and conscientiousness had a negative relationship, whereas agreeableness, extraversion, and openness had a positive influence. Additionally, Eshet and Margaliot [81] found that extraversion and emotional stability have a positive impact on academic integrity. Thus, based on the literature, we posit the following:

H2.

Personality traits correlate with academic misconduct.

2.2. Contextual Characteristics

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the educational systems. The initial identification of the outbreak occurred in December 2019 in Wuhan, China [82]. After three years of the pandemic, in May 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the end of the emergency status [83]. The lockdowns and the changes in the learning environment led to educational challenges like accessibility, adequate learning strategies, and pedagogies, which impacted academic performance and academic integrity rates [29]. Furthermore, the literature attested to a change in studying and learning habits due to the lack of internet connectivity or accessibility, inadequate information and technology equipment, and reduced communication [26].

Learning environments have undergone significant changes, fostering the adoption of innovative teaching methods intertwined with modern technology [84]. In other words, incorporating multimedia technologies into learning environments creates qualitatively different learning experiences in higher education [85]. Examples include the incorporation of information and communication technology [86]. These technological advances have resulted in digitalised learning, such as fully online planned environment (or hybrid or blended) modules combined with traditional face-to-face education [33].

Traditional face-to-face learning is characterised by the use of conventional teaching methods [87], like direct classroom lectures and guiding with immediate feedback in class [85]. Planned online learning includes electronic-based lectures and guiding questions, which may also be tackled on the online platform [85]. Well-planned online learning offers learners enhanced support, responsibility, flexibility, and choice [88]. Planned online learning may be asynchronous (recorded lectures or forums), synchronous (live online meetings and sessions), or both [89]. Asynchronous formats offer the greatest flexibility, allowing students to decide when and how to view lectures. For example, students can watch lecture videos at their convenience and replay them if interrupted. Synchronous is more like in-person classes, offering a framework of fixed lecture times around which students must organise their schedules [90].

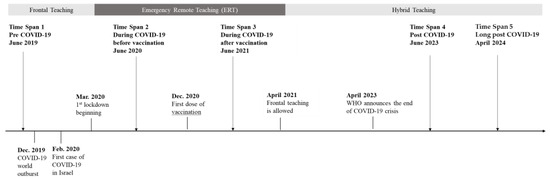

Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) was implemented as an immediate response to the COVID-19 pandemic, transitioning education from face-to-face to online teaching [88], and it was marked by a sudden shift to remote instruction, often without adequate preparation or adaptation [91]. ERT was developed hastily with minimal time and resources [9]. Both professors and students faced stress and challenges during the transition, including concerns about course expectations and miscommunication [92]. Figure 1 depicts the different learning environments and pre-peri and post-COVID-19 timelines in Israel.

Figure 1.

Time Spans and Learning Environments.

The above timeline illustrates the transitions of teaching environments from face-to-face to blended/hybrid due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Initially, the learning environment was face-to-face, and it was predominant until February 2020 (pre-COVID-19 time span). Following the first case of COVID-19 in Israel in February 2020 and the onset of the first lockdown in March 2020, the learning environment changed to emergency remote teaching (ERT), predominantly synchronous (COVID-19 before vaccination time span), and it lasted until December 2020. After the first dose of the vaccine, from January 2021 (COVID-19 after-vaccination time span), emergency remote teaching environments predominated. By April 2021, face-to-face was permitted again, and since May 2023, teaching has transitioned to a blended/hybrid model (post-COVID-19 time span). As of April 2024, blended/hybrid teaching continues (long post-COVID-19 time span).

Research has consistently demonstrated that learning environments significantly impact students’ experiences and outcomes [93], particularly in terms of course enrolment and delivery methods like face-to-face, planned online environments, and emergency remote teaching. Academic integrity breaching (also known as academic misconduct or dishonesty) is a worldwide issue that escalated significantly following the onset of COVID-19 [94]. Prior research revealed that situational variables are strongly associated with academic misconduct [95], such as the shift to online instruction [8]. Eshet et al. [33] observed that, pre-COVID-19, there were higher rates of academic dishonesty in planned online learning compared to face-to-face instruction, while during-COVID-19, higher rates in Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT). Additionally, Maryon et al. [23] found that, during COVID-19, academic misconduct intensified, and Eshet [29] revealed that academic misconduct (plagiarism) rates across various disciplines were higher during unforeseen crises. Thus, based on the above, we posit the following:

H3.

During crisis times (COVID-19), academic misconduct rates accelerate.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

Data were collected from undergraduate students in five Israeli academic institutions studying for bachelor’s degrees in social sciences (Education, Psychology, Sociology, Criminology, and Management). The questionnaires were distributed to students after the end of the course in five different time spans: (a) pre-COVID-19 (June 2019)—face-to-face learning environment; (b) during COVID-19 before vaccination (June 2020)—emergency remote teaching–learning environment; (c) during COVID-19 after vaccination (June 2021)—emergency remote teaching–learning environment; (d) post-COVID-19 (June 2023)—face-to-face with an optional one day of planned online learning (synchronous modality) environment; and (e) long post-COVID-19 (April 2024)—face-to-face with an optional one day of planned online learning (synchronous modality) environment. The sample consisted of 1040 participants; 11% were male, and 89% were female students. Participants’ average age was 24.84 years with a standard deviation of 3.5 years. The questionnaire was delivered online using Qualtrics XM software (Version Number 8 May 2024). We used a stratified sample based on mandatory courses in statistics, computer usage, and research methods. The average time for filling out the questionnaires was 10 min. About 20% of the participants were excluded from the analysis because their survey instruments were incomplete (less than 100%) or carelessly completed.

3.2. Instruments

Learning motivation contained 8 items that were compiled from the Academic Self-Regulation Questionnaire [96]. They were translated into Hebrew by Peled et al. [40] and had acceptable reliability (α = 0.75). The questionnaire explores two types of motivation: extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. An example of an item is, “I do my homework so that the lecturer will think I am a good student”. The participants responded to these questions using a five-point Likert scale where 1 corresponded to not at all true and 5 corresponded to very true. In this study, the level of reliability found was acceptable (α = 0.72).

Personality Traits contained 10 items from the ten-item personality inventory (TIPI) [97]. They were translated into Hebrew by Peled et al. [40] and had acceptable reliability (α = 0.63). The participants responded to these questions using a five-point Likert scale where 1 corresponded to not at all true and 5 corresponded to very true. Each facet includes one positive and one negative keyed item; an example of an item is “I see myself as Extraverted, enthusiastic”. In this study, the level of reliability found was acceptable (α = 0.63).

Academic misconduct contained 8 items that were compiled from the Academic Integrity Inventory. This part of the survey included items related to perceptions of and intentions of academic misconduct according to integrity culture, cheating frequency, and the likelihood of misconduct [38]. It is based on 5 items with a reliability of 0.75 as measured by Cronbach’s alpha. An example of a question is: “How likely are you to consider turning in work done by someone else as your own”. The survey was translated into Hebrew by Peled et al. [40] and had acceptable reliability (α = 0.75). The participants responded to these questions using a five-point Likert scale where 1 corresponded to largely opposed and 5 corresponded to largely agree. In this study, the level of reliability found was acceptable (α = 0.70).

3.3. Plan of Analysis

Data were analysed through SPSS version 28. Descriptive statistics, Reliability analysis, Phi correlation, Pearson correlations, Forced steps regression, and One-way ANOVA were conducted to analyse the data.

4. Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) for each item on the Academic Misconduct scale throughout the different time spans. Students reported moderate agreement (score 70 to 78 on a scale of 1 to 100) with the statement “In my faculty”, indicating that the students understood the procedures related to academic dishonesty.

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation of Academic Misconduct.

There was no multicollinearity between the independent variables (Table 2). Most Pearson correlations were weak, indicating that academic misconduct was a variable comprising a compound of factors.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix of the study variables.

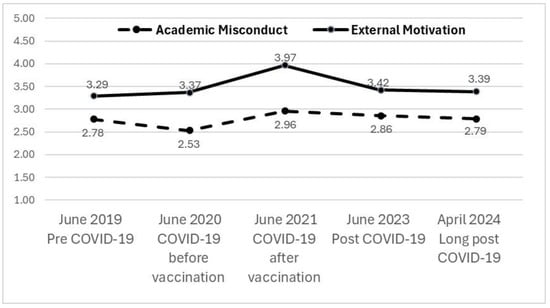

Table 3 presents a one-way ANOVA for academic misconduct between periods. A significant difference was found between the five periods (F(4,1085) = 16.41, p < 0.01). The effect size was medium (Ƞ2 = 0.06). Scheffe test showed no significant difference between pre-COVID-19 and long post-COVID-19. That is, 5 years after the COVID-19 outbreak, the level of academic misconduct returned to the same level as before the pandemic.

Table 3.

One-way ANOVA between periods for Academic Misconduct.

Steps regression (Table 4) revealed that factors increasing academic misconduct were external motivation (β = 0.154) and periods of COVID-19 progression (β = 0.074). Factors reducing academic misconduct were intrinsic motivation (β = −0.193), the personality trait agreeableness (β = −0.167), the personality trait emotional stability (β = −0.090) and the grade point average (β = −0.079). This confirms hypotheses 1, 2, and 3. The predictive model was found to be significant (F(13,909) = 8.41, p < 0.01), with an explained variance percentage of 15.7%.

Table 4.

Forced Steps Regression for Academic Misconduct.

Figure 2 presents the changes in academic misconduct and external motivation throughout the five periods. Both variables showed similar trends, with an overall increase during the pandemic after vaccination took place and a decrease after the pandemic, back to pre-COVID-19 levels.

Figure 2.

Changes in Academic Misconduct (dashed line) and External Motivation (solid line) throughout COVID-19 Time Spans.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Prioritising the consideration of ethical implications is crucial for maintaining the integrity and effectiveness of education delivery [98]. Therefore, our study centred on how contextual variables (a pandemic emergency) affected academic misconduct rates according to personal characteristics (personality traits) and learning motivation. Our research provides valuable insights into the complex dynamics of academic misconduct and underscores the importance of proactive measures to safeguard academic integrity, particularly in times of crisis. The study’s comprehensive approach, across time spans, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, provides a nuanced understanding of how academic misconduct evolves.

First, this research inquired about the relationship between external learning motivation and academic misconduct. Our findings and the literature [72] confirm H1. This may be due to students being nonchalant in their studies and concerned about obtaining their degrees [73]. In other words, students are less motivated to acquire subject knowledge, and academic misconduct becomes a pathway to completing the assignments [76]. This phenomenon aligns with a key aspect of Self-Determination Theory, specifically goal contents theory, which suggests that extrinsic goals are linked to achievement, meaning the instrumentalities of the task rather than deriving satisfaction from the learning process [62]. Another additional explanation may be the lack of instructors’ technological–pedagogical preparedness [34] and lack of spare time or skill to motivate their students to learn externally. Additionally, the change in studying and learning habits, like home-learning and studying during the pandemic lockdown [26], may have prompted academic misconduct by shortcuts to assessments. Thus, there is a need to develop special learning habits during emergency crises, including academic integrity education and literacy.

Next, this study inquired into the relationship between personality traits and academic misconduct. In line with the literature [40,80], the findings showed that agreeableness and emotional stability reduced academic misconduct. Concerning agreeableness, this behaviour could stem from this personality quality, which is associated with instructors’ compliance, cooperative and collaborative learning related to high academic achievement [99], and their tendency toward pro-social behaviour, thus leading to greater autonomous motivation and adhering to social norms, like physical distancing during COVID-19 [100]; additionally, this trait is negatively related to amotivation [99]. Consequently, this discourages academic misconduct. Concerning emotional stability, this behaviour could stem from withdrawal from negative experiences [101], like academic misconduct, and withstands antisocial behaviour.

Finally, we inquired about the differences in academic misconduct levels before, during (pre and post-vaccination), after, and long after COVID-19. Our results showed that academic misconduct rates were far higher during the pandemic period compared to the pre-post and long post-pandemic. Furthermore, the findings exhibited a bouncing back of academic misconduct rates pre- and long post-pandemic. These findings are consistent with the research literature [102]. This may be due to higher educators’ unpreparedness for online teaching [103], the demand for a myriad of pedagogical challenges [98], the effects of learning methods [75], the lack of the physical presence of instructors [33], and ambiguous ethical narratives [29].

On the one hand, there is concern about the pandemic per se. On the other hand, we transmigrated educational subject content to online platforms and acquired the technological skills for it. During Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT), instructors are often inadequately prepared or able to adapt [91], thus decreasing the quality of instruction and lowering learning motivation [104]. In other words, both professors and students faced challenges during this transition and were concerned about course expectations and miscommunication [92]. Thus, there is a lack of spare time or clear policies for addressing ethical issues like academic misconduct. Another explanation may be due to the transition to abrupt online instruction and the increase in the misuse of online sites for misconduct [8].

Summing up, the results suggest that external motivations and changes in the academic environment during the pandemic significantly influenced academic misconduct. The rise in academic misconduct during the pandemic might be linked to a reduced sense of autonomy, as the constraints and challenges of remote learning could have limited students’ control over their academic experience. In addition, students struggling with academic challenges may have been more susceptible to misconduct, especially if they felt they could not meet the required standards on their own. Furthermore, the impact of social influences, such as peer behaviour and external pressures, underscores the need for a supportive academic environment to foster integrity and discourage dishonest behaviour. Consequently, efforts to enhance intrinsic motivation and provide a supportive academic environment could mitigate such behaviours. Additionally, understanding the role of personality traits can help in designing interventions tailored to student characteristics to promote academic integrity.

We conclude from the above that higher education preparedness for academic integrity during an emergency is still a desideratum and that ethical concerns should not be abandoned but be fully addressed during emergency periods. Eradicating—or at least minimising—academic dishonesty is not an easy task and requires a multi-layered approach involving educators, institutions, and students themselves. Moreover, there may be different viewpoints on what academic integrity involves [17].

Consequently, in line with the literature [59,60], higher education should implement comprehensive practices and policies promoting responsibility and honesty. This could be achieved by breaching physical distances and instructing students and staff on alternative pedagogies during emergencies, such as in small workshops and seminars and ethical modules while teaching subject content. In addition, in line with Self-Determination Theory, lecturers can foster autonomy in various learning environments by giving students more control over their schedules and learning methods. They can also encourage a culture of collaboration and peer support within academic settings to strengthen relationships and reduce competitive pressures that may lead to misconduct. Providing academic support services, such as tutoring and mentoring, can help build students’ confidence in their abilities. Additionally, facilitating open discussions about academic integrity can help understand students’ perspectives and develop policies that resonate with their experiences.

Moreover, technological tools, like artificial intelligence or paraphrasing software [55], could be helpful in promoting integrity awareness. For example, instructors may include tasks that inquire about integrity issues in given content knowledge, including artificial intelligence usage and active classroom discussions. These discussions may address misconduct concerns and their consequences for subsequent professional career development. Finally, instructors could allocate group tasks involving students with pro-social personalities (agreeableness and emotional stability) and intrinsic motivation to serve as social agents in deterring academic misconduct.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations. Firstly, as there is a lack of existing literature on the relationship between the research variables, this study adopted an exploratory approach. Data collection relied on subjective self-report questionnaires. Additionally, while our samples were not gender-balanced, they do reflect the general educational gender trends [105]. Nonetheless, we recommend conducting future studies on gender comparisons. Future research could enhance the reliability of the findings by incorporating dyadic data, such as combining self-report measures with objective data obtained through plagiarism detection software. Other future research may include inquiring about the relationship between the different motivations, each of the Big Five Personality Traits, and academic behaviours and time spans.

Next, it is important to acknowledge the limitations associated with a non-longitudinal design. A non-longitudinal approach captures data at a single point in time, which may not fully account for the dynamic and evolving nature of the variables under study. This limits the ability to observe changes or trends over time, potentially overlooking long-term effects or developments. As a result, the findings should be interpreted with caution, particularly when generalising or predicting future outcomes. Future research could benefit from a longitudinal approach to more comprehensively understand the temporal aspects of the phenomena being studied.

Like any empirical research, this study represents a specific framework analysing and reflecting a particular practice based on its data. In essence, our research offers a nuanced theoretical perspective on a broader socio-cultural phenomenon. This suggests that research, theory, and practice could all potentially gain from similar tests focusing on additional contexts utilising different predictors and comparing them with other unpredicted emergencies (i.e., war situations or natural disasters). Additionally, our samples lacked gender balance. Therefore, we suggest conducting future studies to explore gender comparisons and cultural diversity.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Orot Israel College of Education (protocol code 2019001; January 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Participants consent was waived as the research did not involve direct human contact or relationships with participants.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would also like to express our gratitude to Ariane Cukierkorn, Information Specialist, for her helpful and constructive comments and suggestions, and for her help proofreading and editing the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tatnall, A.; Fluck, A. Twenty-five years of the education and the information technologies journal: Past and future. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 1359–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peimani, N.; Kamalipour, H. Online education and the COVID-19 outbreak: A case study of online teaching during lockdown. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butakor, P.K.; Kakutia, T.; Shah, S.M.M.; Hunt, E. Higher education challenges in the era of Covid-19, from the perspective of educators and students (Ghana, Georgia and Pakistan Cases)–A literature Review. ESI Prepr. 2022, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, R.; Fatima, A.; Elbayoumi Salem, I.; Allil, K. Teaching and learning delivery modes in higher education: Looking back to move forward post-COVID-19 era. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2023, 21, 100805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, E.J.; Lazarony, P.J. A look back at mandatory online instruction: Preserving a record of student preferences and experiences. J. Educ. Bus. 2024, 99, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almossa, S.Y.; Alzahrani, S.M. Lessons on maintaining assessment integrity during COVID-19. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2022, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorbehbahani, F.; Mohammadi, A.; Aminazadeh, M. A systematic review of research on cheating in online exams from 2010 to 2021. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 8413–8460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, B.; Cazan, A.-M. Did the COVID-19 pandemic lead to an increase in academic misconduct in higher education? High. Educ. 2024, 87, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamage, K.A.A.; Silva, E.K.d.; Gunawardhana, N. Online delivery and assessment during COVID-19: Safeguarding academic integrity. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, M.H.E.M.; Larson, L.R.; Sharaievska, I.; Rigolon, A.; McAnirlin, O.; Mullenbach, L.; Cloutier, S.; Vu, T.M.; Thomsen, J.; Reigner, N. Psychological impacts from COVID-19 among university students: Risk factors across seven states in the United States. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshet, Y.; Grinautsky, K.; Steinberger, P. To behave or not (un)ethically? The meditative effect of mindfulness on statistics anxiety and academic dishonesty moderated by risk aversion. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2024, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltayeb, F. Mindfulness and its relation to academic procrastination among university students. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 9, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, W.O. Academic dishonesty among undergraduates of oduduwa university, ipetu-modu, nigeria: Moderating roles of personality traits and task value. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. Couns. 2021, 6, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söylemez, N.H. A problem in higher education: Academic dishonesty tendency. Bull. Educ. Res. 2023, 45, 23–48. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, E.J. Integrating academic integrity: An educational approach. In Second Handbook of Academic Integrity; Eaton, S.E., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 305–324. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, S.E. Comprehensive academic integrity (CAI): An ethical framework for educational contexts. In Second Handbook of Academic Integrity; Eaton, S.E., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, A. Academic integrity in the time of contradictions. Cogent Educ. 2023, 10, 2289307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdà-Navarro, A.; Touza-Garma, C.; Pozo-Llorente, T.; Comas Forgas, R. Analysis of the prevalence, evolution, and severity of dishonest behaviors of Spanish graduate students: The vision of academic heads. Prax. Educ. 2023, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, D.; Salgado, J.F.; Moscoso, S. Personality, intelligence, and counterproductive academic behaviors: A meta-analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 120, 504–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Shen, Z. Science map of academic misconduct. Innovation 2024, 5, 100593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal Arellano, W.M.; Galarza Parra, J.N.; Villavicencio Reinoso, J.M.; Quito Ochoa, J.F. A study on academic dishonesty among English as a foreign language students. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, C.; Tiwari, S.; Yan, S.; Williams, J. Emergency remote teaching environment: A conceptual framework for responsive online teaching in crises. Inf. Learn. Sci. 2020, 121, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryon, T.; Dubre, V.; Elliott, K.; Escareno, J.; Fagan, M.H.; Standridge, E.; Lieneck, C. COVID-19 academic integrity violations and trends: A rapid review. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberger, P.; Eshet, Y.; Grinautsky, K. No anxious student is left behind: Statistics anxiety, personality traits, and academic dishonesty—Lessons from COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholes, J.; Sullivan, A.; Self, S. The impact of long-term disruptions on academic success in higher education and best practices to help students overcome them. J. High. Educ. Theory Pract. 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jereb, E.; Jerebic, J.; Urh, M. Studying habits in higher education before and after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Athens J. Educ. 2023, 10, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortjass, M.; Mkhize-Mthembu, N. Reflecting on teaching in the higher education context during the Covid-19 era: A collaborative self-study project. Educ. Res. Soc. Chang. 2023, 12, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mospan, N. Trends in emergency higher education digital transformation during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2023, 20, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshet, Y. The plagiarism pandemic: Inspection of academic dishonesty during the COVID-19 outbreak using originality software. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 3279–3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, S.E. Global perspectives on academic integrity: Introduction. In Second Handbook of Academic Integrity; Eaton, S.E., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sefcik, L.; Striepe, M.; Yorke, J. Mapping the landscape of academic integrity education programs: What approaches are effective? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauginienė, L.; Gaižauskaitė, I.; Glendinning, I.; Kravjar, J.; Ojsteršek, M.; Ribeiro, L.; Odiņeca, T.; Marino, F.; Cosentino, M.; Sivasubramaniam, S.; et al. Glossary for Academic Integrity; European Network for Academic Integrity: Brno, Czech Republic, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Eshet, Y.; Steinberger, P.; Grinautsky, K. Does statistics anxiety impact academic dishonesty? Academic challenges in the age of distance learning. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2022, 18, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshet, Y.; Steinberger, P.; Grinautsky, K. Relationship between statistics anxiety and academic dishonesty: A comparison between learning environments in social sciences. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntire, A.; Calvert, I.; Ashcraft, J. Pressure to plagiarise and the choice to cheat: Toward a pragmatic reframing of the ethics of academic integrity. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, B. Your students are cheating more than you think they are. Why? Educ. Res. Theory Pract. 2020, 31, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Comas Forgas, R.; Cerdà-Navarro, A.; Touza Garma, C.; Moreno Herrera, L. Prevalence and factors associated with academic plagiarism in freshmen students of Social Work and Social Education: An empirical analysis. RELIEVE Rev. Electrónica Investig. Evaluación Educ. 2023, 29, 1e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisamore, J.L.; Stone, T.H.; Jawahar, I.M. Academic integrity: The relationship between individual and situational factors on misconduct contemplations. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 75, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.X.; Fanaian, M.; Zhang, N.M.; Lea, X.; Geale, S.K.; Gielis, L.; Razaghi, K.; Evans, A. Academic dishonesty in university nursing students: A scoping review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2024, 154, 104752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peled, Y.; Eshet, Y.; Barczyk, C.; Grinautski, K. Predictors of academic dishonesty among undergraduate students in online and face-to-face courses. Comput. Educ. 2019, 131, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, D.L.; Treviño, L.K.; Butterfield, K.D. Cheating in academic institutions: A decade of research. Ethics Behav. 2001, 11, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Yperen, N.W.; Hamstra, M.R.W.; van der Klauw, M. To win, or not to lose, at any cost: The impact of achievement goals on cheating. Br. J. Manag. 2011, 22, S5–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Chen, C.; Luo, L. The examination of the relationship between learning motivation and learning effectiveness: A mediation model of learning engagement. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckhausen, J. Integrating and instigating research on person and situation, motivation and volition, and their development. Motiv. Sci. 2020, 6, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspar, K.; Burtniak, K.; Rüth, M. Online learning during the Covid-19 pandemic: How university students’ perceptions, engagement, and performance are related to their personal characteristics. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 16711–16730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E. When do individual differences matter? A paradoxical theory of personality coherence. Psychol. Inq. 1993, 4, 247–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaninah, F.S.E.; Mohd Noor, M.H. The impact of big five personality trait in predicting student academic performance. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2024, 16, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.; Rose, R.; Hewig, J. The relation of big five personality traits on academic performance, well-being and home study satisfaction in corona times. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 368–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, T.; Cotarlan, C. Contract cheating by STEM students through a file sharing website: A Covid-19 pandemic perspective. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2021, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottiar, Z.; Byrne, G.; Gorham, G.; Robinson, E. An examination of the impact of COVID-19 on assessment practices in higher education. Eur. J. High. Educ. 2024, 14, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, T.; Prickett, T.; Vasiliou, C.; Chitare, N.; Watson, I. Exploring computing students’ post-pandemic learning preferences with workshops: A UK institutional case study. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education, Turku, Finland, 7–12 July 2023; pp. 173–179. [Google Scholar]

- du Rocher, A.R. Active learning strategies and academic self-efficacy relate to both attentional control and attitudes towards plagiarism. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Bertel, L.B.; Lyngdorf, N.E.R.; Markman, A.O.; Andersen, T.; Ryberg, T. Emerging digital practices supporting student-centered learning environments in higher education: A review of literature and lessons learned from the covid-19 pandemic. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 1673–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Zhang, J.; Guan, D.; Zhao, X.; Si, J. Antecedents of statistics anxiety: An integrated account. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 144, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas Forgas, R.; Lancaster, T.; Curiel Marín, E.; Touza Garma, C. Automatic paraphrasing tools: An unexpected consequence of addressing student plagiarism and the impact of COVID in distance education settings. Prax. Educ. 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foltýnek, T.; Dlabolová, D.; Anohina-Naumeca, A.; Razı, S.; Kravjar, J.; Kamzola, L.; Guerrero-Dib, J.; Çelik, Ö.; Weber-Wulff, D. Testing of support tools for plagiarism detection. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2020, 17, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.; Miller, V.; Marchel, C.; Moro, R.; Kaplan, B.; Clark, C.; Musilli, S. Academic violence/bullying: Application of Bandura’s eight moral disengagement strategies to Higher Education. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2019, 31, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khathayut, P.; Walker-Gleaves, C.; Humble, S. Using the theory of planned behaviour to understand thai students’ conceptions of plagiarism within their undergraduate programmes in higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2022, 47, 394–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdà-Navarro, A.; Touza, C.; Morey-López, M.; Curiel, E. Academic integrity policies against assessment fraud in postgraduate studies: An analysis of the situation in Spanish universities. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foltýnek, T.; Glendinning, I. Impact of policies for plagiarism in higher education across Europe: Results of the project. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2015, 63, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirca, C.L.; Billen, E. Predicting academic dishonesty: The role of psychopathic traits, perception of academic dishonesty, moral disengagement and motivation. J. Acad. Ethics 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshet, Y.; Dickman, N.; Ben Zion, Y. Academic integrity in the HyFlex learning environment. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, S.L. Self-Determination Theory (SDT): Perspective, Applications and Impact; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, B. Understanding the Socioemotional Learning in Schools: A Perspective of Self-Determination Theory; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Conceptualizations of intrinsic motivation and self-determination. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 11–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in distance education: A self-determination perspective. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2024, 38, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suharnadi, P.; Neviyarni, S.; Nirwana, H. The role and function of learning motivation in improving student academic achievement. Manajia J. Educ. Manag. 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can. Psychol. 2008, 49, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory: When mind mediates behavior. J. Mind Behav. 1980, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Neviyarni, S.; Nirwana, H. Efforts to increase student learning motivation from a psychological perspective. J. Psychol. Couns. Educ. 2024, 2, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmi, T.S.; Neviyarni, S. The role of learning motivation (extrinsic and intrinsic) and its implications in the learning process. Int. J. Educ. Dyn. 2022, 5, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrawati, D. Using extrinsic motivation in learning english during covid-19 pandemic. J. High. Educ. Theory Pract. 2024, 24, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holubnycha, L.; Besarab, T.; Pavlishcheva, Y.; Kadaner, O.; Khodakovska, O. E-learning at the tertiary level in and after pandemic. Acta Paedagog. Vilnensia 2022, 48, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, H.; Firdiyanti, R. Predicting academic dishonesty based on competitive orientation and motivation: Do learning modes matter? Int. J. Cogn. Res. Sci. Eng. Educ. (IJCRSEE) 2023, 11, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krou, M.R.; Fong, C.J.; Hoff, M.A. Achievement motivation and academic dishonesty: A meta-analytic investigation. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 33, 427–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, V.V.; Araujo, R.d.C.R.; de Oliveira, I.C.V.; Goncalves, M.P.; Milfont, T.; de Holanda Coelho, G.L.; Santos, W.; de Medeiros, E.D.; Soares, A.K.S.; Monteiro, R.P. A short version of the Big Five Inventory (BFI-20): Evidence on construct validity. Rev. Interam. Psicol. 2021, 55, e1312. [Google Scholar]

- Sleep, C.E.; Lynam, D.R.; Miller, J.D. A comparison of the validity of very brief measures of the Big Five/Five-Factor Model of personality. Assessment 2021, 28, 739–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammadov, S. Big Five personality traits and academic performance: A meta-analysis. J. Personal. 2022, 90, 222–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giluk, T.L.; Postlethwaite, B.E. Big Five personality and academic dishonesty: A meta-analytic review. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 72, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshet, Y.; Margaliot, A. Does creative thinking contribute to the academic integrity of education students? Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 925195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokhrel, S.; Chhetri, R. A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. High. Educ. Future 2021, 8, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannis, P.Φ.; Evdokia, A.V. Online Education during COVID-19 and beyond: Opportunities, Challenges, and Its Future—The Greek Perspective; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Valtonen, T.; Leppänen, U.; Hyypiä, M.; Kokko, A.; Manninen, J.; Vartiainen, H.; Sointu, E.; Hirsto, L. Learning environments preferred by university students: A shift toward informal and flexible learning environments. Learn. Environ. Res. 2021, 24, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, N.T.T.; De Wever, B.; Valcke, M. Face-to-face, blended, flipped, or online learning environment? Impact on learning performance and student cognitions. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2020, 36, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesny, A.; Rivas, D.P.; Haro, S.P.D. Business school professors’ teaching approaches and how they change. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2021, 20, 50–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broeckelman-Post, M.; Malterud, A.; Arciero, A. Can course format drive learning? Face-to-face and and lecture-lab models of the fundamentals of communication course. Basic Commun. Course Annu. 2020, 32, 79–105. [Google Scholar]

- Palombi, T.; Galli, F.; Mallia, L.; Alivernini, F.; Chirico, A.; Zandonai, T.; Zelli, A.; Lucidi, F.; Giancamilli, F. The effect of emergency remote teaching from a student’s perspective during COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from a psychological intervention on doping use. In Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, F.; Kumar, S.; Ritzhaupt, A.D.; Polly, D. Bichronous online learning: Award-winning online instructor practices of blending asynchronous and synchronous online modalities. Internet High. Educ. 2023, 56, 100879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravizza, S.M.; Meram, N.L.; Hambrick, D.Z. Synchronous or asynchronous learning: Personality and online course format. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2023, 207, 112149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas-Abril, C.A. Telecollaboration in emergency remote language learning and teaching. In Proceedings of the 2020 Sixth International Conference on E-Learning (Econf), Sakheer, Bahrain, 6–7 December 2020; pp. 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho-Zuñiga, C.; Peña-Becerril, M.; Cuevas-Cancino, M.D.L.O.; Avilés-Rabanales, E.G. Gains from the transition from face-to-face to digital/online modality to improve education in emergency. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1197396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mørk, G.; Magne, T.A.; Carstensen, T.; Stigen, L.; Åsli, L.A.; Gramstad, A.; Johnson, S.G.; Bonsaksen, T. Associations between learning environment variables and students’ approaches to studying: A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koscielniak, M.; Enko, J.; Gąsiorowska, A. “I Cheat” or “We Cheat?” The structure and psychological correlates of individual vs. Collective examination dishonesty. J. Acad. Ethics 2024, 22, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awdry, R.; Ives, B. Students cheat more often from those known to them: Situation matters more than the individual. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2021, 46, 1254–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Connell, J.P. Self-Regulation Questionnaire. Unpublished Manuscript. 1989. Available online: https://selfdeterminationtheory.org/self-regulation-questionnaires/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Gosling, S.D. Ten-Item Personality Inventory-(TIPI). University of Texas, USA. 2021. Available online: https://gosling.psy.utexas.edu/scales-weve-developed/ten-item-personality-measure-tipi/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Sato, S.N.; Condes Moreno, E.; Rubio-Zarapuz, A.; Dalamitros, A.A.; Yañez-Sepulveda, R.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Navigating the new normal: Adapting online and distance learning in the post-pandemic era. Educ. Sci. 2023, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chue, K.L. Examining the influence of the big five personality traits on the relationship between autonomy, motivation and academic achievement in the twenty-first-century learner. In Motivation, Leadership and Curriculum Design: Engaging the Net Generation and 21st Century Learners; Koh, C., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, A.M.; Holding, A.C.; Levine, S.; Powers, T.; Koestner, R. Agreeableness and conscientiousness promote successful adaptation to the covid-19 pandemic through effective internalisation of public health guidelines. Motiv. Emot. 2022, 46, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, P.M.; Proença, T.; Carozzo-Todaro, M.E. A systematic review on well-being and ill-being in working contexts: Contributions of self-determination theory. Pers. Rev. 2024, 53, 375–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshet, Y. Examining the Dynamics of Plagiarism: A Comparative Analysis Before, During, and after the COVID-19 Pandemic; Department of Behavioral Science, Zefat Academic College: Zefat, Israel, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- McManus, R.; Logan, A.; Wilders, D.; Pennycook, C. “A world of possibilities”: The future of technology in higher education, insights from the COVID-19 experience. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, B. University students experience the COVID-19 induced shift to remote instruction. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2021, 18, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bureau of Statistics. Students at Institutions of Higher Education; Central Bureau of Statistics: Thapathali, Kathmandu, Nepal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).