Factors Influencing Physical Activity and Sports Practice among Young People by Gender: Challenges and Barriers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

2.2. Sample

2.3. Instrument

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

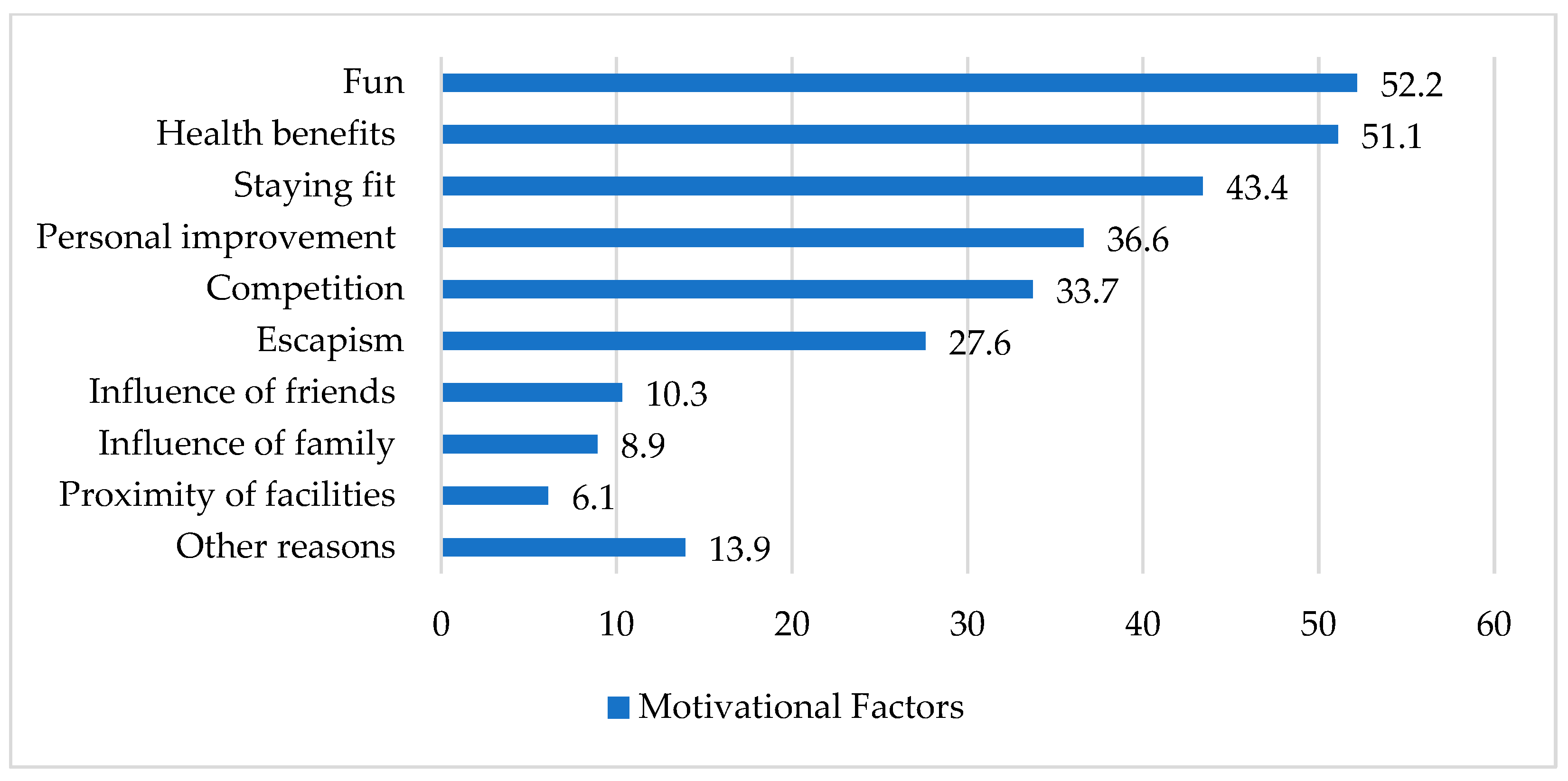

3.1. Factors Influencing Motivation in the Practice of PAS

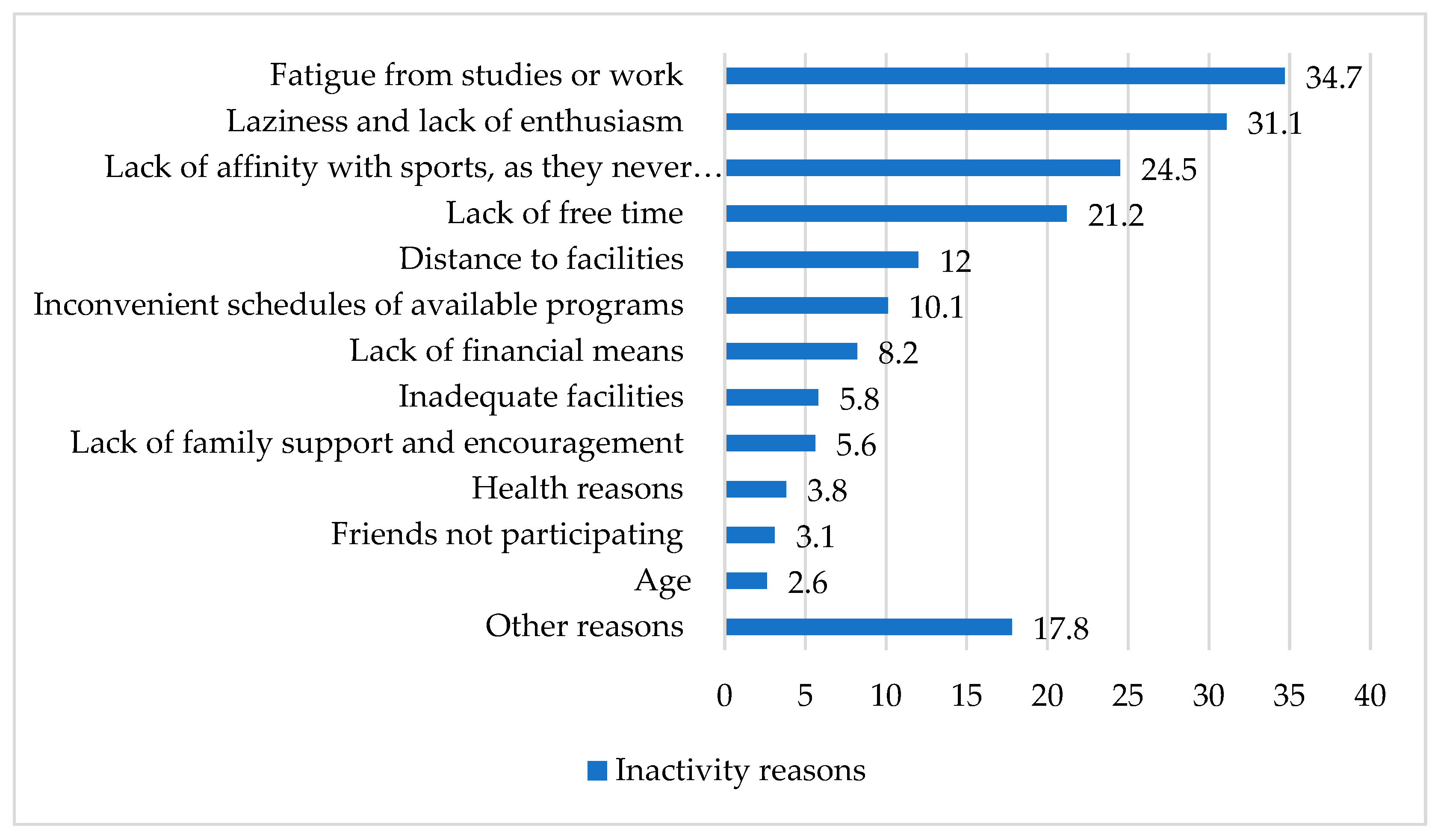

3.2. Factors Influencing Demotivation and Abandonment of Physical Activity and Sports (PAS)

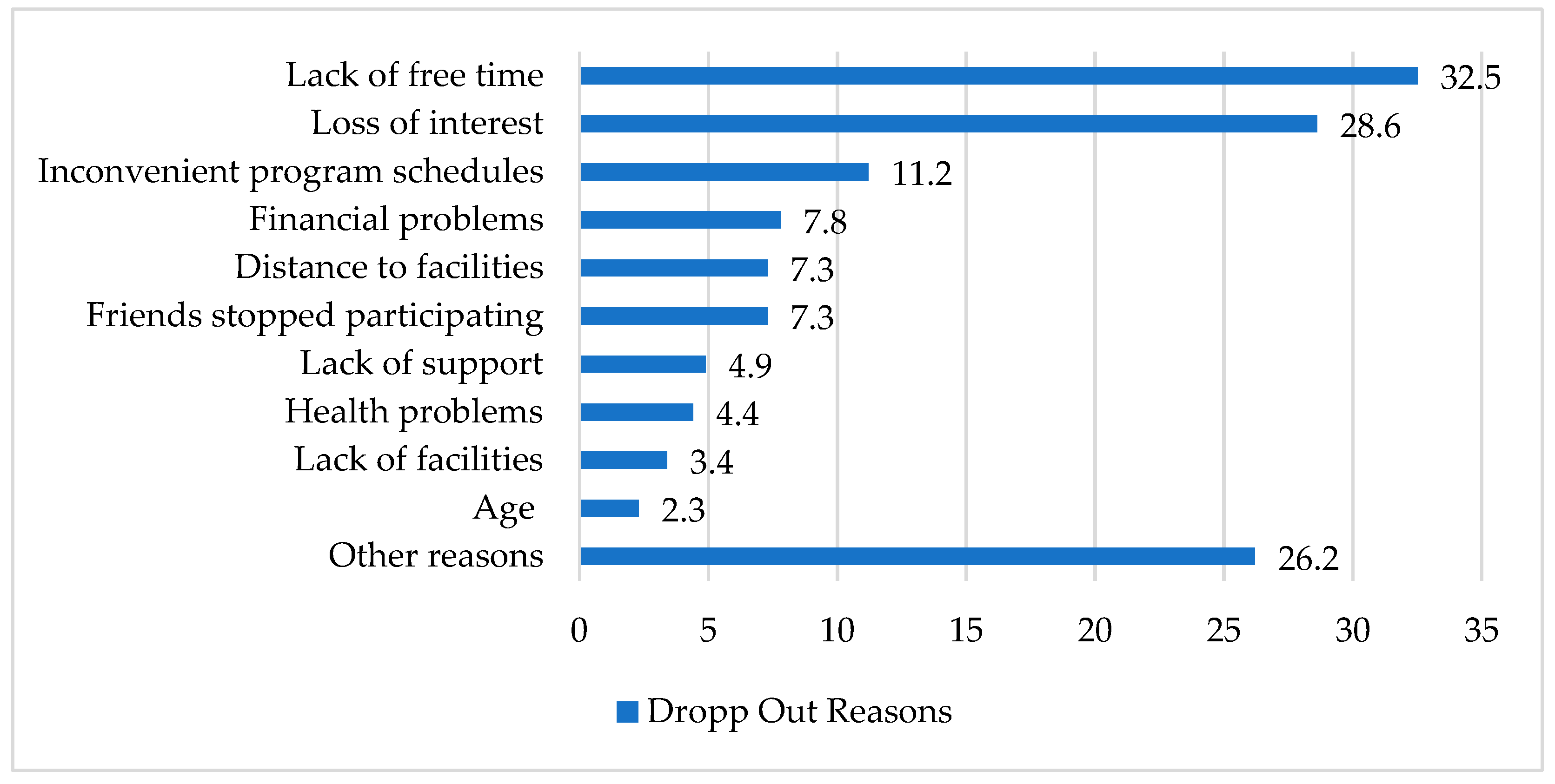

3.3. Factors Influencing the Abandonment of Physical Activity and Sports (PAS)

4. Discussion

4.1. Interests and Influencing Factors in Youth Participation in PAS

4.2. Factors Influencing Demotivation and Abandonment of PAS

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baños, R.; Marentes, M.; Zamarripa, J.; Baena-Extremera, A.; Ortiz-Camacho, M.; Duarte-Félix, H. Influencia de la satisfacción, aburrimiento e importancia de la educación física extraescolar en adolescentes mexicanos. Cuad. De Psicol. Del Deporte 2019, 19, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asociación Española de Pediatría. Consejos Sobre Actividad Física Para Niños Y Adolescentes. Available online: https://www.aeped.es/grupo-trabajo-actividad-fisica/documentos/consejos-sobre-actividad-fisica-ninos-y-adolescentes (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Desiderio, W.A.; Bortolazzo, C. Actividad física recreativa en niños y adolescentes: Situación actual, indicaciones y beneficios. Rev. De La Asoc. Médica Argent. 2019, 132, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Recomendaciones Mundiales Sobre Actividad Física Para la Salud; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación Española de la Nutrición. Sedentarismo en Niños y Adolescentes Españoles: Resultados del Estudio Científico ANIBES; Fundación Española de la Nutrición: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.; Jiang, J. Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew Res. Cent. 2018, 31, 1673–1689. [Google Scholar]

- Simón-Montañes, L.; Solana, A.A.; García-González, L.; Catalán, A.A.; Sevil-Serrano, J. “Hyperconnected” adolescents: Sedentary screen time according to gender and type of day. Eur. J. Hum. Mov. 2019, 43, 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- García-Martín, S.; Cantón-Mayo, I. Uso de tecnologías y rendimiento académico en estudiantes adolescentes. Comun. Rev. Científica De Comun. Y Educ. 2019, 27, 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Fomby, P.; Goode, J.A.; Truong-Vu, K.-P.; Mollborn, S. Adolescent Technology, Sleep, and Physical Activity Time in Two U.S. Cohorts. Youth Soc. 2021, 53, 585–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilugrón-Aravena, F.; Molina, T.; Gras-Pérez, M.E.; Font-Mayolas, S. Hábitos alimentarios, obesidad y calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en adolescentes chilenos. Rev. Médica De Chile 2020, 148, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Dios, T.R.; Gordo, A.R.; Rey, I.P. Estudio cualitativo sobre las percepciones en alimentación, prácticas alimentarias y hábitos de vida saludables en población adolescente. Rev. Española De Salud Pública 2023, 97, e202305037. [Google Scholar]

- Conger, S.A.; Toth, L.P.; Cretsinger, C.; Raustorp, A.; Mitáš, J.; Inoue, S.; Bassett, D.R. Time trends in physical activity using wearable devices: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies from 1995 to 2017. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2022, 54, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar, A.; Vernetta, M. Satisfacción e importancia de la Educación Física en centros educativos de secundaria. Rev. Iberoam. De Cienc. De La Act. Física Y El Deporte 2022, 11, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sember, V.; Jurak, G.; Duric, S.; Starc, G. Decline of physical activity in early adolescence: A 3-year cohort study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230893. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7065740/ (accessed on 19 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Boraita, R.J.; Ibort, E.G.; Torres, J.M.D.; Alsina, D.A. Factores asociados a un bajo nivel de actividad física en adolescentes de La Rioja (España). An. De Pediatría 2022, 96, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, R.W.; Rombaldi, A.J.; Ricardo, L.I.C.; Hallal, P.C.; Azevedo, M.R. Prevalência de comportamento sedentário de escolares e fatores associados. Rev. Paul. De Pediatr. 2016, 34, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portela-García, C.A.; Vidarte-Claros, A. Niveles de actividad física y gasto frente a pantallas en escolares: Diferencias de edad y género. Univ. Salud 2021, 23, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturricastillo, A.; Irigoyen, J.Y. El nivel del disfrute con la actividad física en adolescentes: Educación física vs. actividad física extraescolar. EmásF Rev. Digit. De Educ. Física 2016, 39, 30–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, J.C. Abandono de la Práctica Deportiva. 2019. Available online: https://ridum.umanizales.edu.co/xmlui/bitstream/handle/20.500.12746/3537/jrivera-arti%CC%81culo.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Blanco, J.R.; Valenzuela, M.C.S.; Benítez-Hernández, Z.P.; Fernández, F.M.; Jurado, P.J. Barreras para la práctica de ejercicio físico en universitarios mexicanos comparaciones por género. Retos Nuevas Tend. En Educ. Física Deporte Y Recreación 2019, 36, 80–82. [Google Scholar]

- Graf, S.; Cecchini, M. Current and Past Trends in Physical Activity in Four OECD Countries; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Castedo, A.; Domínguez-Alonso, J.; Pin, I. Barreras percibidas para la práctica del ejercicio físico en adolescentes: Diferencias según sexo, edad y práctica deportiva. Rev. De Psicol. Del Deporte 2020, 29, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Peral-Suárez, Á.; Cuadrado-Soto, E.; Perea, J.M.; Navia, B.; López-Sobaler, A.M.; Ortega, R.M. Physical activity practice and sports preferences in a group of Spanish schoolchildren depending on sex and parental care: A gender perspective. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, M.H.T.; Ocampo, D.B.; Reyes, A.L.J.; Sosa, H.I.R.; González, A.G. Motivos de la inactividad física infantil: Una visión de niños, padres y entrenadores. MHSalud 2021, 18, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignoli, H. Motivos de No Realización de Ejercicio Físico Y/O Actividad Físico-Deportiva en Estudiantes de Educación Media Superior. Bachelor’s Thesis, Instituto Universitario Asociación Cristiana de Jóvenes, Montevideo, Uruguay, 2019. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12729/221 (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Ocampo, D.B.; Reyes, A.L.J.; Vasquez, M.H.T.; Sosa, H.I.R.; González-González, A. Actividad física, sedentarismo y preferencias en la práctica deportiva en niños: Panorama actual en México. Cuad. De Psicol. Del Deporte 2022, 22, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, J.U.; Sagredo, A.J.V.; Rivera, C.F.; Hetz, K.; Adasme, G.P.; Valderrama, F.P. Percepción de autoconcepto físico en estudiantes de enseñanza secundaria en clases de Educación Física. Retos Nuevas Tend. En Educ. Física Deporte Y Recreación 2023, 49, 510–518. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo, A.G.; Jiménez, M.A. Influencia de la Actividad Físico-Deportiva en el rendimiento académico, la autoestima y el autoconcepto de las adolescentes: El caso de la isla de Tenerife. Retos Nuevas Tend. En Educ. Física Deporte Y Recreación 2022, 46, 120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Velásquez, L.Z. Actividad física e imagen corporal de los adolescentes: Revisión teórica. EmásF Rev. Digit. De Educ. Física 2022, 79, 112–126. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, J.G.; de los Fayos, E.J.G.; Toro, E.O. Avanzando en el camino de diferenciación psicológica del deportista. Ejemplos de diferencias en sexo y modalidad deportiva. Anu. De Psicol. UB J. Psychol. 2014, 44, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Temple, V.A.; Crane, J.R.; Brown, A.; Williams, B.; Bell, R.I. Recreational activities and motor skills of children in kindergarten. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2016, 21, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, S.C.; Temple, V.A. The relationship between fundamental motor skill proficiency and participation in organized sports and active recreation in middle childhood. Sports 2017, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela-Pino, I.; López-Castedo, A.; Martínez-Patiño, M.J.; Valverde-Esteve, T.; Domínguez-Alonso, J. Gender differences in motivation and barriers for the practice of physical exercise in adolescence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccetti, A.; Franco-Álvarez, E.; Coterón-López, J.; Gómez, V. Estado de flow e intención de práctica de actividad física en adolescentes argentinos. Rev. De Psicol. PUCP 2021, 39, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monforte, J.; Colomer, J.Ú. ‘Como una chica’: Un estudio provocativo sobre estereotipos de género en educación física. Retos Nuevas Tend. En Educ. Física Deporte Y Recreación 2019, 36, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Guerrero, M.D.; Vanderloo, L.M.; Barbeau, K.; Birken, C.S.; Chaput, J.P.; Tremblay, M.S. Development of a consensus statement on the role of the family in the physical activity, sedentary, and sleep behaviours of children and youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandbu, Å.; Bakken, A.; Stefansen, K. The continued importance of family sport culture for sport participation during the teenage years. Sport Educ. Soc. 2020, 25, 931–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisternas, Y.F.C.; Gómez, B.; González, A.; Pasten, E. Clima familiar deportivo y nivel de actividad física en adolescentes. Retos Nuevas Tend. En Educ. Física Deporte Y Recreación 2022, 45, 440–445. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, A.L.J.; Ocampo, D.B.; Vasquez, M.H.T.; Sosa, H.I.R.; González, A.G. Los padres como modelos de la actividad física en niños y niñas mexicanos. Retos Nuevas Tend. En Educ. Física Deporte Y Recreación 2022, 43, 742–751. [Google Scholar]

- Mora, J.L.; Velert, C.P. Las relaciones sociales y su papel en la motivación hacia la práctica de actividad física en adolescentes: Un enfoque cualitativo. Retos Nuevas Tend. En Educ. Física Deporte Y Recreación 2020, 37, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Iannotti, R.J.; Haynie, D.L.; Perlus, J.G.; Simons-Morton, B.G. Motivation and planning as mediators of the relation between social support and physical activity among US adolescents: A nationally representative study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otero-Wandurraga, J.A.; Cohen, D.D.; Delgado-Chinchilla, D.M.; Camacho-López, P.A.; Amador-Ariza, M.A.; Rueda-Quijano, S.M.; López-Jaramillo, J.P. Facilitadores y barreras percibidos en la práctica de la actividad física en adolescentes escolarizados en Piedecuesta (Santander), en 2016: Análisis cualitativo. Rev. Fac. Nac. De Salud Pública 2020, 38, e77476. [Google Scholar]

- Hellín, P.; Moreno, J.A.; Rodríguez, P.L. Motivos de práctica físico-deportiva en la región de Murcia. Cuad. De Psicol. Del Deporte 2004, 4, 101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, J.J.; García, E.; Rosa, A.; Rodríguez, P.L.; Moral, J.E.; López, S. Relación entre la intención de realizar actividad física y la actividad física extraescolar. Rev. De Psicol. 2019, 37, 389–405. [Google Scholar]

- Moscoso, D.; Piedra, J. El colectivo LGTBI en el deporte como objeto de investigación sociológica. Estado de la cuestión. Rev. Española De Sociol. 2019, 28, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedra, J. Actitudes hacia la diversidad sexual en el deporte. In Aportaciones a la Investigación Sobre Mujeres Y Género, Proceedings of the V Congreso Universitario Internacional «Investigación Y Género», Sevilla, Spain, 3–4 July 2014; Casado, R., Flecha, R., Guil, A., Padilla, M.T., Vázquez, I., Martínez, M.d.R., Eds.; Unidad para la Igualdad de la Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Díaz, A.; Cabeza-Ruiz, R. Actitudes hacia la diversidad sexual en el deporte en estudiantes de educación secundaria. Retos Nuevas Tend. En Educ. Física Deporte Y Recreación 2020, 38, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamazares-López, A.; Nieto-Rodríguez, J.; Ventola-Rodríguez, N.; Moral-García, J.E. Actividad física escolar y extraescolar en estudiantes adolescentes, diferentes motivaciones y beneficios para la salud. Papeles Salmant. De Educ. 2020, 24, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávalos-Ramos, M.A.; Pascual-Galiano, M.T.; Vidaci, A.; Vega-Ramírez, L. Future Intentions of Adolescents towards Physical Activity, Sports, and Leisure Practices. Healthcare 2024, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanova, M.; Sollar, T. Enjoyment of physical activity and perception of success in sports high school students. Ad Alta-J. Interdiscip. Res. 2019, 9, 249–251. Available online: http://www.magnanimitas.cz/ADALTA/0901/papers/A_romanova.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Spray, C.M.; Warburton, V.E. What Motivates Young Athletes to Play Sport? Front. Young Minds 2022, 10, 686291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, J.C.; de Oliveira Filho, G.G.; de Lira, C.A.B.; da Silva, R.A.D.; Alves, E.d.S.; Benvenutti, M.J.; Rosa, J.P.P. Motivation Levels and Goals for the Practice of Physical Exercise in Five Different Modalities: A Correspondence Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 793238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, R.B.; Herring, M.P.; Campbell, M.J. Associations Between Motivation and Mental Health in Sport: A Test of the Hierarchical Model of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddle, S.J.; Gorely, T. Sitting Psychology: Towards a Psychology of Sedentary Behaviour. In Routledge Companion to Sport and Exercise Psychology; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 720–740. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Prieto, I.; Giné-Garriga, M.; Canet-Vélez, O. Barreras y motivaciones percibidas por adolescentes en relación con la actividad física. Estudio cualitativo a través de grupos de discusión. Rev. Española De Salud Pública 2020, 93, e201908047. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, M.R.L.; Hansen, A.F.; Elmose-Østerlund, K. Motives and Barriers Related to Physical Activity and Sport across Social Backgrounds: Implications for Health Promotion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, A.; Fisher, C.; Cross, D. “Why Don’t I Look Like Her?” How Adolescent Girls View Social Media and Its Connection to Body Image. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Vélez, A.; Jiménez-Parra, J.F. Factores que influyen en la percepción del alumnado sobre la importancia de la educación física. Sport TK Rev. Euroam. De Cienc. Del Deporte 2022, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-González, V.; Gómez-López, M.; Granero-Gallegos, A. Relación entre la satisfacción con las clases de Educación Física, su importancia y utilidad y la intención de práctica del alumnado de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Rev. Complut. De Educ. 2019, 30, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-López, M.; Granero-Gallegos, A.; Baena-Extremera, A.; Bracho, C.; Pérez, F.J. Efectos de interacción de sexo y práctica de ejercicio físico sobre las estrategias para la disciplina, motivación y satisfacción con la Educación Física. Rev. Iberoam. De Diagnóstico Y Evaluación Psicológica 2015, 2, 6–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rico-Díaz, J.; Arce-Fernández, C.; Padrón-Cabo, A.; Peixoto-Pino, L.; Abelairas-Gómez, C. Motivaciones y hábitos de actividad física en alumnos universitarios. Retos Nuevas Tend. En Educ. Física Deporte Y Recreación 2019, 36, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávalos-Ramos, M.A.; Martínez, M.A.; Merma, G. La disposición hacia la actividad física y deportiva: Narrativas de los adolescentes escolarizados. Sportis 2017, 3, 486–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-Extremera, A.; Granero-Gallegos, A.; Sánchez-Fuentes, J.A.; Martínez-Molina, M. Apoyo a la Autonomía en Educación Física: Antecedentes, Diseño, Metodología y Análisis de la Relación con la Motivación en Estudiantes Adolescentes. Retos Nuevas Tend. Educ. Fís. Dep. Recreación 2013, 24, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Leyton-Román, M.; Núñez, J.L.; Jiménez-Castuera, R. The Importance of Supporting Student Autonomy in Physical Education Classes to Improve Intention to Be Physically Active. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.E.; Ullrich-French, S.; Hargreaves, E.A.; McMahon, A.K. The effects of mindfulness and music on affective responses to self-paced treadmill walking. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2020, 9, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 11–12 | 13–15 | 16–18 | Male | Female | Other Genders | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Much | 47.8 | 46.4 | 46.1 | 59.5 | 33.6 | 46.7 | 46.6 |

| Enough | 33.5 | 31.7 | 37.0 | 27.5 | 40.1 | 20.0 | 33.3 |

| Little | 15.5 | 15.3 | 14.6 | 8.8 | 21.4 | 16.7 | 15.2 |

| None | 1.9 | 4.5 | 1.8 | 3.3 | 13.3 | 3.4 | 3.4 |

| No answer | 1.2 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 3.3 | 1.6 | |

| 100 |

| 11–12 | 13–15 | 16–18 | Male | Female | Other Genders | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 82.0 | 76.3 | 74.4 | 83.1 | 71.3 | 66.7 | 76.9 |

| No | 18.0 | 23.7 | 25.6 | 16.9 | 28.7 | 33.3 | 23.1 |

| Motivation | 11–12 | 13–15 | 16–18 | Male | Female | Other Genders | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feeling competent | 34.8 | 43.4 | 39.3 | 50.0 | 30.8 | 53.3 | 40.9 |

| Friends | 8.7 | 11.7 | 8.2 | 12.3 | 8.2 | 13.3 | 10.3 |

| Competition | 29.8 | 34.8 | 33.8 | 46.3 | 21.2 | 30.0 | 33.7 |

| Fun | 53.4 | 50.5 | 54.3 | 56.5 | 48.3 | 40.0 | 52.0 |

| Staying fit | 31.1 | 43.6 | 52.1 | 51.4 | 36.1 | 33.3 | 43.4 |

| Family | 9.3 | 8.2 | 10.0 | 9.5 | 8.2 | 10.0 | 8.9 |

| Personal improvement | 32.9 | 37.6 | 37.0 | 44.2 | 28.9 | 36.7 | 36.6 |

| Health | 39.8 | 51.7 | 58.0 | 53.0 | 49.4 | 46.7 | 51.1 |

| Proximity of facilities | 5.6 | 5.1 | 8.7 | 7.9 | 4.0 | 10.0 | 6.1 |

| Escapism | 18.0 | 25.8 | 38.8 | 25.0 | 30.3 | 26.7 | 27.6 |

| Other reasons | 15.5 | 15.3 | 9.6 | 13.4 | 14.2 | 16.7 | 13.9 |

| 11–12 | 13–15 | 16–18 | Male | Female | Other Genders | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Easy | 59.6 | 53.7 | 51.6 | 63.0 | 45.5 | 53.3 | 54.2 |

| Motivating | 32.9 | 21.5 | 21.9 | 25.2 | 22.6 | 16.7 | 23.7 |

| Useful | 38.5 | 28.4 | 27.9 | 33.3 | 26.8 | 30.0 | 30.1 |

| Promotes Extracurriculars | 25.5 | 21.9 | 18.7 | 21.8 | 21.0 | 33.3 | 21.8 |

| More Important | 10.6 | 11.2 | 9.1 | 14.4 | 6.5 | 13.3 | 10.5 |

| Less Important | 16.8 | 22.1 | 26.0 | 16.9 | 27.0 | 26.7 | 22.1 |

| Sufficient | 23.6 | 29.9 | 32.0 | 27.5 | 30.5 | 36.7 | 29.3 |

| Insufficient | 8.1 | 12.1 | 18.7 | 14.6 | 11.2 | 16.7 | 13.0 |

| 11–12 | 13–15 | 16–18 | Male | Female | Other Genders | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of aptitude | 24.1 | 28.1 | 16.1 | 19.2 | 27.6 | 20.0 | 24.3 |

| Friends not practising | 3.4 | 3.3 | 5.4 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 20.0 | 3.9 |

| Lack of financial means | 3.1 | 3.4 | 8.3 | 10.7 | 12.2 | 10.0 | 8.3 |

| Laziness | 34.5 | 33.1 | 26.8 | 31.5 | 30.9 | 40.0 | 31.6 |

| Fatigue | 27.6 | 34.7 | 37.5 | 27.4 | 39.0 | 30.0 | 34.5 |

| Lack of support | 6.9 | 6.6 | 3.6 | 1.4 | 8.1 | 10.0 | 5.8 |

| Age | 3.4 | 1.7 | 5.4 | 4.1 | 1.6 | 10.0 | 2.9 |

| Health | 3.4 | 3.3 | 5.4 | 4.1 | 3.3 | 10.0 | 3.9 |

| Distance to facilities | 6.9 | 10.7 | 17.9 | 5.5 | 14.6 | 30.0 | 12.1 |

| Inadequate facilities | 3.4 | 4.1 | 10.7 | 5.5 | 5.7 | 10.0 | 5.8 |

| Lack of free time | 13.8 | 19.0 | 30.4 | 8.2 | 30.1 | 10.0 | 21.4 |

| Incompatible schedules | 13.9 | 9.9 | 8.9 | 6.8 | 12.2 | 10.0 | 10.2 |

| Other reasons | 17.2 | 15.7 | 21.4 | 20.5 | 17.1 | 0.0 | 17.5 |

| 11–12 | 13–15 | 16–18 | Male | Female | Other Genders | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | 0.0 | 5.8 | 3.6 | 5.5 | 4.1 | 0.0 | 4.4 |

| Financial problems | 3.4 | 8.3 | 8.9 | 2.7 | 9.8 | 20.0 | 7.8 |

| Age | 0.0 | 2.5 | 3.6 | 1.4 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 2.4 |

| Friends not participating | 6.9 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 8.2 | 7.3 | 0.0 | 7.3 |

| Loss of interest | 24.1 | 31.4 | 25.0 | 27.4 | 28.5 | 40.0 | 28.6 |

| Lack of support | 0.0 | 5.8 | 5.4 | 2.7 | 4.9 | 20.0 | 4.9 |

| Lack of free time | 13.8 | 32.2 | 42.9 | 24.7 | 36.6 | 40.0 | 32.5 |

| Lack of facilities | 0.0 | 3.3 | 5.4 | 1.4 | 4.1 | 10.0 | 3.4 |

| Distance to facilities | 3.4 | 8.3 | 7.1 | 4.1 | 7.3 | 30.0 | 7.3 |

| Inconvenient schedules | 13.8 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 9.6 | 10.6 | 30.0 | 11.2 |

| Other reasons | 34.5 | 26.4 | 21.4 | 28.8 | 26.0 | 10.0 | 26.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ávalos-Ramos, M.A.; Vidaci, A.; Pascual-Galiano, M.T.; Vega-Ramírez, L. Factors Influencing Physical Activity and Sports Practice among Young People by Gender: Challenges and Barriers. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 967. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090967

Ávalos-Ramos MA, Vidaci A, Pascual-Galiano MT, Vega-Ramírez L. Factors Influencing Physical Activity and Sports Practice among Young People by Gender: Challenges and Barriers. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(9):967. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090967

Chicago/Turabian StyleÁvalos-Ramos, Mª Alejandra, Andreea Vidaci, Mª Teresa Pascual-Galiano, and Lilyan Vega-Ramírez. 2024. "Factors Influencing Physical Activity and Sports Practice among Young People by Gender: Challenges and Barriers" Education Sciences 14, no. 9: 967. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090967

APA StyleÁvalos-Ramos, M. A., Vidaci, A., Pascual-Galiano, M. T., & Vega-Ramírez, L. (2024). Factors Influencing Physical Activity and Sports Practice among Young People by Gender: Challenges and Barriers. Education Sciences, 14(9), 967. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090967