2.2. School Leadership and School Improvement

Studies on school development and improvement also emphasize the significance of school leaders, especially from the perspective of the continuous improvement process targeting individual schools, e.g., [

8,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43].

In many countries, the efforts made to improve schools have illustrated that neither top-down measures (e.g., reform measures from education ministries and authorities) alone, nor exclusively bottom-up approaches (e.g., changes initiated by individuals) produce the desired outcomes. Instead, the combination and systematic synchronization of both has proven most effective e.g., [

44]. Moreover, improvement is viewed as a continuous process with different phases, which follow their individual rules e.g., [

38,

45,

46]. Innovations also need to be institutionalized after their initiation and implementation at the individual school level so that they will become a permanent part of the school’s culture, comprising its structures, atmosphere, and daily routines [

47]. The goal is to develop problem-solving, creative, and self-renewing schools that have sometimes been described as learning organizations. Therefore, the emphasis is placed on the priorities to be chosen by each school since it is the center of the change process. Thereby, the core purposes of schools—education and instruction—are the focal points because the teaching and learning processes play a decisive role in student success [

48]. Thus, both individual teachers and school leaders are of great importance. They are the essential change agents who will have significant influence on whether a school will develop into a learning organization or fail to do so, e.g., [

5,

32,

49]. For all phases of the school development process, school leadership is considered vital and is held responsible for keeping in mind the school as a whole and adequately coordinating individual activities during the improvement processes (for the decisive function of leadership in the development of individual schools, see, e.g., studies conducted as early as the 1980s [

50,

51,

52]). Leaders are also required to create the internal conditions necessary for the continuous development and increasing professionalization of teachers and are held accountable for developing a cooperative school culture. In this regard, research emphasizes the “modeling” function of school leaders e.g., [

53,

54,

55].

2.3. Professional Development (PD) and Support

PD is essential for both aspiring and experienced school leaders, focusing on maintaining high standards of leadership. Many countries have implemented comprehensive programs that support leaders through various career stages and offer targeted short-term interventions for specific developmental needs [

56].

The past decades have witnessed a growing knowledge base in the field of education leadership development. Distinct characteristics of leadership development programs are beginning to form, and there is a rising demand for studies on the associated effects and outcomes [

57].

Several international trends in PD can be identified. We have followed up on an earlier study on the PD of leaders in 15 countries (see also [

58,

59]). We also draw on the project called Professional Learning through Reflection promoted by Feedback and Coaching (PROFLEC, see

CPSM.EduLead.net (accessed on 1 July 2024)), funded by the European Union (2012–2014). PROFLEC reviewed international trends focusing on the training and development of school leaders in 10 countries: Australia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, England, the German-speaking countries (Austria, Germany, and Switzerland), Norway, and Sweden [

56].

Key perspectives in PD curricula demonstrate increasing attention to the needs of participants and recommend that demands derived from school evaluations be considered and practices be improved by bridging theory and action. This orientation toward needs and application is expected to improve the impacts and sustainability of PD [

60,

61]. To become better aligned with the needs of participants, a few PD approaches integrate diagnostic means, audits, assessments of needs, and feedback opportunities as components of training and PD.

In general, the use of a wide range of strategies and methods will likely be the most-effective approach. Those responsible for planning and implementing professional training and development are strongly advised to use a variety of methods. This approach helps individual participants learn and be motivated to apply the lessons for performance improvement.

Despite differences in cultural and institutional traditions, a number of internationally shared trends in the PD of school leaders can be observed, including holistic approaches (not only content instruction but also promotion of motivation and reflection), personal development instead of training for a role, orientation toward each school’s core purposes (from knowledge acquisition to its creation and development), experience and application orientation, and multiple methods of using different ways of learning (e.g., workshops, self-assessments, and feedback) [

56].

A study on preparing school leaders [

11] shows that “effective principal preparation and development programs could transform principals’ practice and increase their success by proactively recruiting dynamic, instructionally focused educators; developing and applying strong knowledge of instructional leadership, organizational development, and change management practices; and offering coaching, feedback, and opportunities for reflection in purposeful communities of practice” [

12] (p. v). Key factors include meaningful, authentic, and applied learning opportunities; curricula focused on developing people, instruction, and organization; expert mentoring or coaching; and collegial learning. Further studies demonstrate the importance of reflection and practice-oriented leadership approaches used for effective learning and for their impacts on the organizational level e.g., [

11,

12,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67]. Even though PD differs in each career phase of a school leader, these mechanisms are shown to be general key factors.

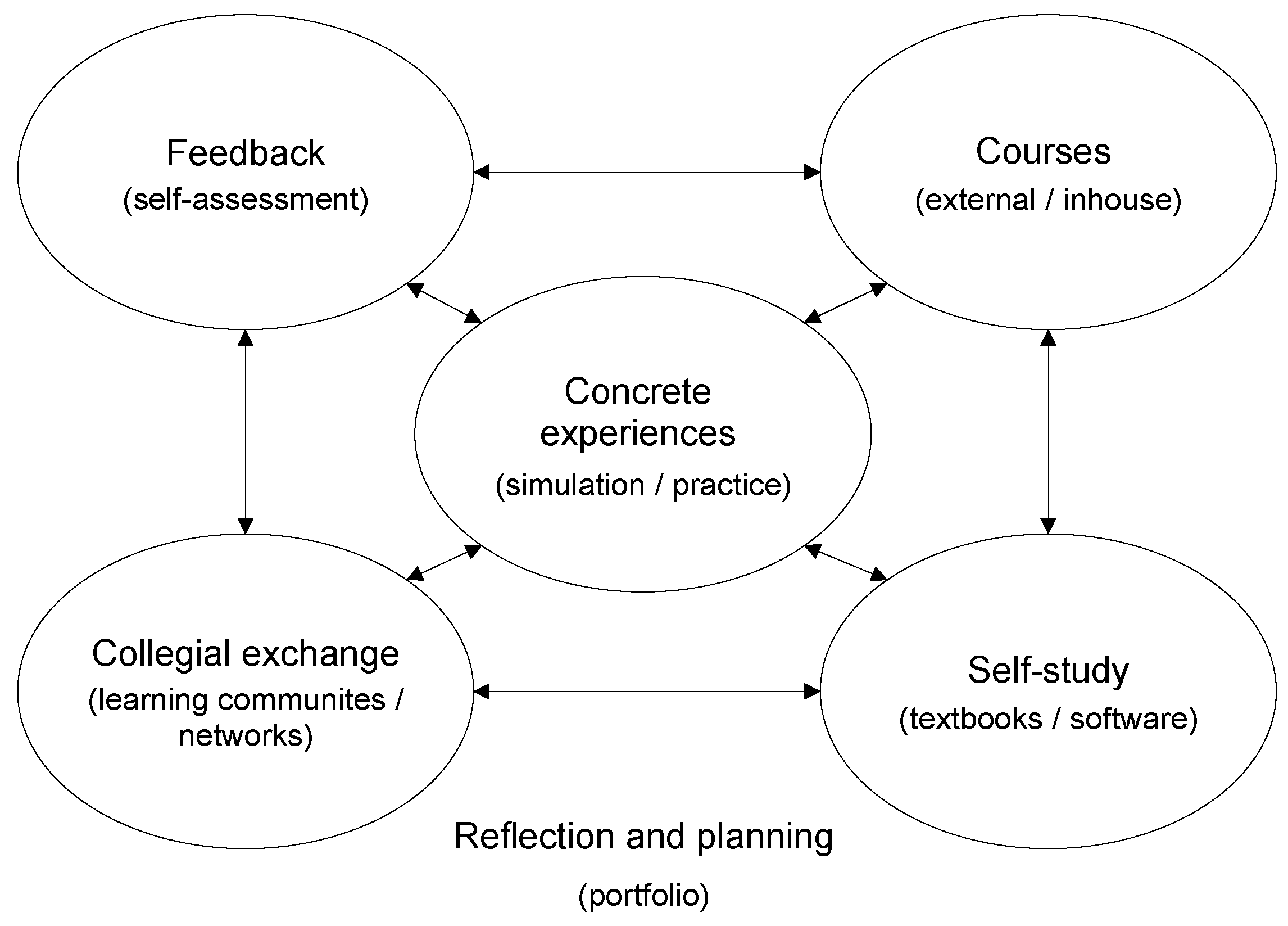

A study suggests multiple learning approaches that integrate courses, self-study, problem-based learning, simulation or practices, and peer learning in communities and networks (see

Figure 1) [

61].

We conclude that it is not only the use of different learning approaches that matters in general but also, in particular, how they are conceptually linked and how this linkage is implemented and then experienced by participants.

Models of the effectiveness of other learning environments, such as those known from school and teaching research, can be used as starting points for a model of the effectiveness of PD. In teaching research, models of learning opportunities have become widely utilized, whose origins can be traced back to Fend’s work [

68,

69]. One of the numerous modifications and further developments of such models is Helmke’s utilization of that of teaching effectiveness e.g., [

70,

71,

72]. Another model is presented by Ditton [

73], who (in addition to the processual nature) focuses on the multilevel character of the school system.

In determining the different levels of impact, we assume that the perception of the program—in terms of its expected relevance for practices, usefulness, and participant satisfaction—should be considered as processes involving the participants themselves. The perception of the program thereby does not represent its impacts. Our definition of impact goes beyond the subjective views of participants; it includes an external perspective and measurable indicators.

Different levels in the evaluation of PD have been described. For instance, Kirkpatrick describes four levels of evaluation [

74]:

Level 1. Reaction (participant satisfaction based on setting, content, methods, etc.)

Level 2. Learning (cognitive learning success and increase of knowledge)

Level 3. Behavior (success in transferring content to action)

Level 4. Results (positive organizational changes as results of the above)

Guskey [

75,

76], Mujjs and Lindsay [

77], and Muijs et al. [

78] each describe a model of evaluation comprising five levels:

Level 1. Participants’ reactions

Level 2. Participants’ learning

Level 3. Organizational support and change

Level 4. Participants’ use of new knowledge and skills

Level 5. Student learning outcomes

The issue of the impacts of multiple approaches to PD and support is closely connected to those of school leadership and school effectiveness. Regarding school leadership, Muijs and Huber [

6] provide a literature review of studies and meta-studies of school leader effectiveness showing indirect impacts on student achievement through various school qualities.

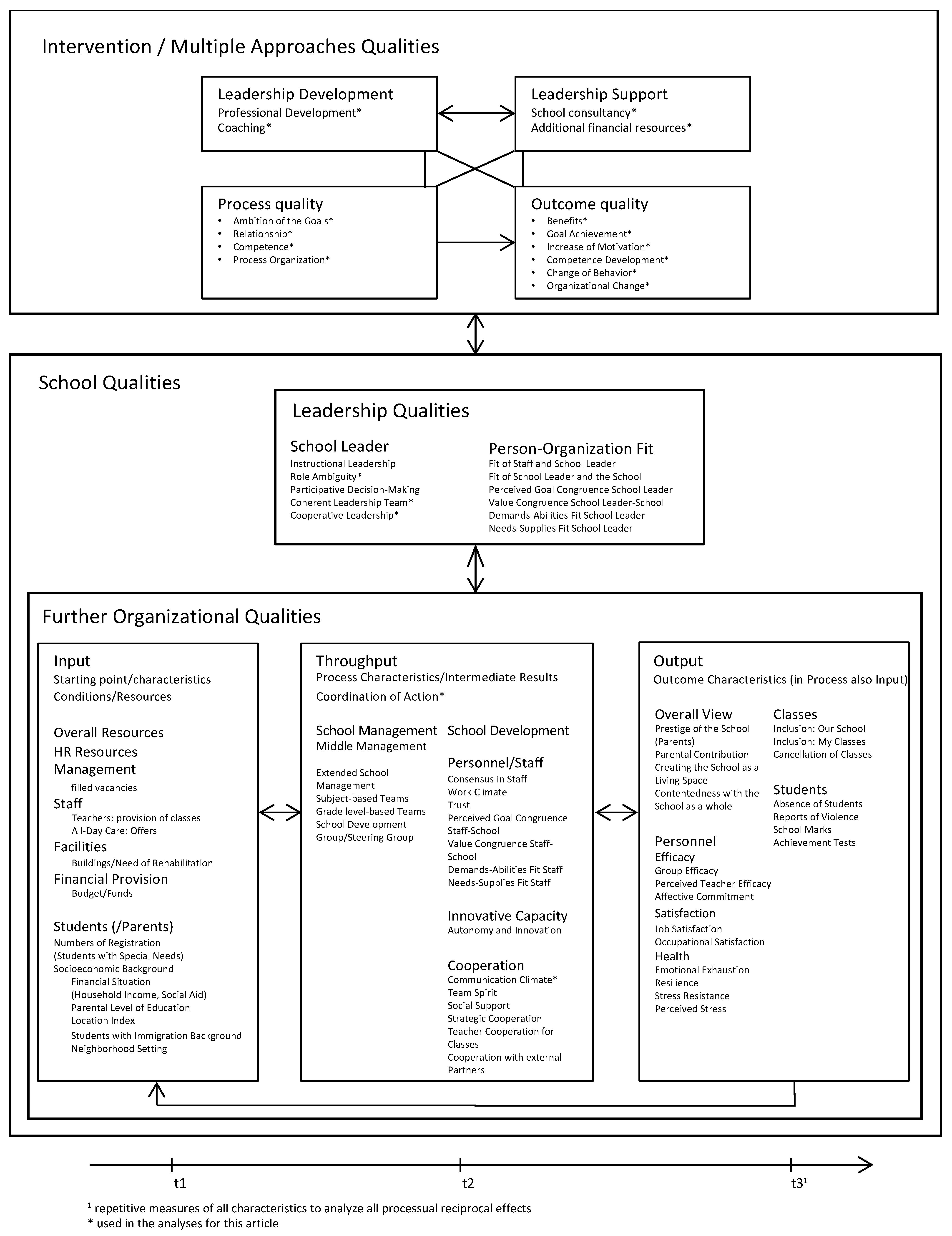

The framework for our empirical research differentiates between qualities of the intervention and qualities of the school (see

Figure 2).

The quality of the interventions demonstrates different but complementary approaches to leadership development, on the one hand, and leadership support for school development on the other hand. Each approach is analyzed with a set of process qualities, as well as outcome qualities.

The model integrates the various forms of impact level, as stated above. Moreover, as a structural component model building on Cronbach’s work [

79] (see also [

80] (p. 776)), school quality is organized into input, throughput, and output characteristics.

School quality is analyzed with various forms of leadership qualities, particularly focusing on the school leader. Further organizational qualities in the form of various input, throughput, and output characteristics are considered, too.

For the schools involved in the multiple approaches to develop and support school leadership, general conditions and resources can be described as input characteristics. These include personnel, material, and financial resources, as well as the characteristics of the student body. Examples of operationalization are provided in the visualization (see

Figure 2) (e.g., whether the school management position is filled). The coordination of action can be regarded as throughput, which is shaped by school management and school development. Characteristics of school quality are modeled as output at the organizational level, while learner characteristics, especially student results (e.g., performance outcomes), are modeled as output at the student level.

Theoretically, in this study, we assume a moderation of effects, from process qualities to outcome qualities, that can be outlined as follows: The support of the school management by concerted action following the interventions promotes the school’s coordination of action—that is, the promotion of strategic and tailor-made personnel management strengthens the school management—and thus, above all, new, strengthened, or further developed in its competence. This, in turn, expands middle management and the work of the school development steering group. This expansion increases the management capacity of the school as a whole, in turn promoting the work of school development. As a result, strategically oriented cooperation, geared toward learning processes, can be expanded, the coordination of actions can be increased, and the quality of the school can be further developed. This increase in quality can then have beneficial impacts on teaching–learning arrangements and student results. Good student results in turn lead to a higher prestige for the school and to an enhanced professional image and self-image for those working in the school.

Of course, quality characteristics at the student and organizational levels also influence the coordination of actions in terms of school management and school development. The visualization (see

Figure 2) marks these interdependencies with arrows.

To strengthen schools in their overall coordination of action and to ensure their further development within the framework of traditional school development work, various stakeholders need their own scopes of actions and responsibilities, as well as resources. School improvement also requires the professionalization of school stakeholders, who increase their motivation, competence, legitimacy, and social acceptance through intensive school development support, further training, and coaching.