1. Introduction

In today’s society, dominated by knowledge and innovation, technology’s pervasive influence extends across all facets of life, from personal to institutional [

1,

2]. Recent years have witnessed an unprecedented surge in the demand for digital learning worldwide, catalyzed by the convergence of technological advancements and evolving pedagogical paradigms [

3,

4]. At the forefront of this dynamic landscape, artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged, promising to revolutionize teaching and learning practices [

5]. In this context, educators are compelled to acquire and impart competencies that transcend mere information and communication technology literacy [

6]. AI is broadly defined as the capacity of digital systems to execute tasks historically reserved for human cognition [

7]. Its associated technologies, such as speech-to-text software, have further enhanced its capabilities. The intersection of AI and education affords more customized and inclusive learning experiences, heralding a new era in education.

Specifically, large language models (LLMs) and generative AI (GenAI) have promptly gained prominence in the realm of human–computer interaction in the past few years, bridging the communication chasm between humans and machines by enabling computers to comprehend and synthesize human-like content such as text or video by discerning patterns and structures from existing data [

8,

9]. Among the emerging GenAI technologies, chatbots, also known as conversational agents, stand out. A chatbot refers to a computer algorithm mimicking human language through “a text-based dialog system using natural language processing” [

10]. Chatbots are typically integrated into webpages or messengers, offering facile online access to virtual interlocutors. Their ability to simulate human conversations and automate services has led to their burgeoning prevalence across various domains, including education [

11,

12].

2. Literature Review

2.1. AI and Language Education

Technology has long been a critical element in language education, a fact corroborated by the cumulative research in computer-assisted language learning [

13]. Numerous studies have posited that GenAI offers distinct benefits, such as customizable input, rapid responses, autonomy, and the capacity to function as a virtual tutor, learning companion, or a teacher’s assistant [

14]. On the other hand, the practical implementation and efficacy of these benefits in real-world EFL classrooms remain under-researched, with a predominance of studies focusing on perceived potential rather than empirical evidence. Concerns have also been raised regarding the potential for over-reliance on these tools, the development of superficial learning strategies, and the ethical considerations surrounding data privacy and algorithmic bias [

15,

16,

17]. However, the use of LLMs in education is gaining steam, and the domain of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) is not the exception [

18]. In recent years, chatbots have been incorporated into English language education to revolutionize and optimize teaching practices [

19,

20].

Perhaps the most celebrated chatbot today is the Conditional Generative Pre-trained Transformer, or ChatGPT, a publicly accessible LLM designed to provide responses to textual requests. Since its release in late 2022, it has experienced exponential uptake [

21]. ChatGPT’s capacity to generate vast volumes of content has made it a popular tool for teaching and learning, which is purported to answer users’ questions and propose solutions to learning problems, thereby boosting educational efficacy [

22,

23].

The rapid advancement of AI promises sizable changes in language education. Hence, the impact of ChatGPT on EFL settings is a relevant and opportune topic. Essentially, AI-powered virtual conversational agents appear to represent the only really innovative technology type in contemporary education. Other educational technologies have either had sufficient time to cease being innovative (e.g., mobile learning) or have never been extensively deployed in educational systems due to affordability and/or implementation issues, as in the case of virtual reality-based learning.

Given that publicly available generative chatbots were introduced as recently as 1.5 years ago at the time of writing, their utility in academia remains largely unexplored. Nevertheless, the impending introduction of AI-based chatbots in education

en masse will require educators to attain AI-specific literacy [

24]. AI literacy refers to “a combination of abilities that empower individuals to critically analyze AI technologies, engage in productive communication and collaboration with AI, and make effective use of AI as a tool” [

25]. This definition broadly aligns with the concept of digital competence, which is characterized as “a collection of the competencies and skills required to understand and use digital technologies in educational practices” [

26]. However, the AI component may present specific challenges. Despite amplified technology-related competencies among teachers since the coronavirus pandemic [

27], sophisticated and manifold applications of GenAI instruments necessitate a broader skill set.

2.2. Technological Pedagogical and Content Knowledge (TPACK) Framework

The TPACK framework, formulated by Mishra and Koehler [

28], offers a holistic model for identifying the necessary knowledge educators must have to effectively incorporate technology into their instruction [

29]. This framework is organized into seven interrelated knowledge domains: the core domains are Technological Knowledge (TK), Pedagogical Knowledge (PK), and Content Knowledge (CK). When these core domains intersect, they create the composite domains of Technological Pedagogical Knowledge (TPK), Technological Content Knowledge (TCK), and Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK). TCK refers to the understanding of how technology can create new representations for specific content. TPK involves understanding how various technologies can be used in teaching and how teaching might change as a result of using particular technologies. At the confluence of these domains lies the seventh domain, TPACK, highlighting the cohesive understanding required to merge technology with pedagogical techniques and content presentation effectively [

30]. The cultivation of TPACK among educators is crucial for the successful integration of technology in education, thus highlighting the need for continuous professional growth in this field [

31]. In this study, teachers’ AI literacy is operationalized through three technology-centric dimensions of the TPACK framework: TCK, TPK, and TPACK. These dimensions are particularly pertinent as they encapsulate the integration of technology with both the subject matter and instructional methods, allowing us to directly assess the impact of the intervention on teachers’ ability to effectively leverage ChatGPT in their teaching practices.

2.3. Motivation for This Study

While teachers have made significant strides in incorporating technology into their teaching practices, there is still room for development in terms of effectively leveraging AI tools in educational contexts [

32,

33]. Building on the extant strengths of educators, there is a need to further hone their skills and competencies in AI usage to unlock its full potential in teaching and learning [

34]. Typically, professional development programs are designed to address such issues. However, to the best of our knowledge, currently available empirical research on educators’ professional development has placed extremely limited attention on the skills required to leverage LLMs within various educational scenarios. Although sporadic local efforts—such as those by Han et al. [

35]—to explore the use of GenAI-based tools to support educators, the majority of studies apropos GenAI-informed solutions in L2 education are non-experimental perception surveys (e.g., [

36,

37]) or theoretical works, e.g., [

38,

39,

40].

This study attempts to fill this research void by conducting a guided prompt-driven ChatGPT integration in EFL teaching. It seeks to obtain quantitative and qualitative perspectives on how interacting with the conversational agent using specifically engineered complex prompts affects EFL teachers’ AI literacy and how they ponder the experience. Teachers’ mastery in adopting the generative dialog system will be gauged through the lens of the TPACK framework.

The following two research questions guided this investigation:

How does prompt-driven ChatGPT integration into EFL teaching influence the proficiency of EFL teachers in employing ChatGPT?

What are the teachers’ perceptions of the effectiveness and prospects of ChatGPT in amending EFL education based on their experiences during the eight-week intervention?

This study is in line with the worldwide trend of integrating digital technologies into learning settings and adds to the scholarly examination of digital technology within education. It is pioneering in its empirical exploration of the effect of GenAI on educators’ AI literacy, paving the way for further research in this domain. Additionally, the findings of this study are anticipated to provide guidance to those crafting educational policies, as well as to curriculum designers and instructors of teacher development courses, regarding the inclusion of GenAI competencies into educational programs.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Data Collection

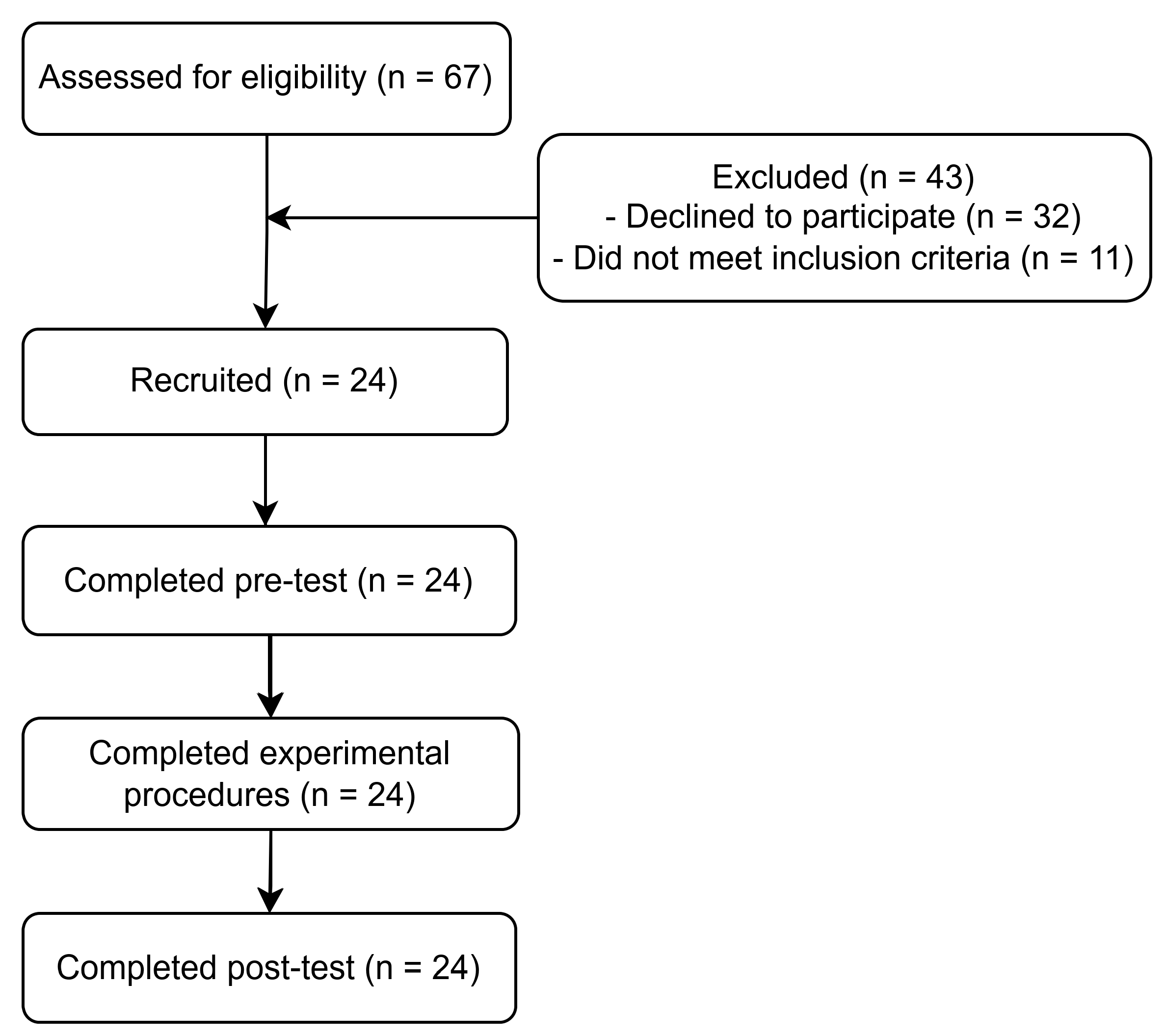

The research involved a purposive sample of 24 EFL teachers (22 females and 2 males, aged between 25 and 43) from three universities. The selection of participants was determined by their availability and willingness to participate. Two inclusion criteria were used: (a) being an in-service university EFL teacher (to ensure a representative sample) and (b) the ability to complete a paper–pencil assessment pre-test and post-test at the corresponding author’s institution (to prevent cheating). Specifically, participants were selected based on their regular teaching schedules that allowed for engagement with the research activities and their expressed interest in integrating ChatGPT into their pedagogical practices, which was established through initial email invitations and follow-up confirmations. Teachers who responded positively and were able to commit to the study schedule were included. Potential bias in the sample selection may have stemmed from the reliance on volunteers, who might have inherently been more motivated. However, purposive sampling was chosen to ensure a focused and committed group of participants who were likely to engage deeply with the intervention and provide sufficient data for analysis. Approval for the research was commissioned by the ethics review board of the first author’s university (Ref. No. EHУ KV.6-59). Upon this step, invitation letters were emailed to all potential participants, detailing the objectives of the research, the procedures for data gathering, teachers’ expected involvement, and their rights, including the freedom to opt out of the study at any stage without facing any negative consequences.

Following the participant recruitment phase, a baseline assessment of ChatGPT literacy was conducted. An online introductory workshop for those who consented to participate was held by the researchers to outline all research steps, specifics, potential issues, and tips. The workshop began with a brief introduction to ChatGPT and its capabilities and limitations. Participants were guided through the process of accessing and interacting with the chatbot, ensuring they could navigate the interface effectively. The researchers emphasized the importance of crafting clear and specific prompts to obtain the most relevant and useful outputs from ChatGPT. Teachers were explicitly informed that ChatGPT is a public chatbot and, as such, they were advised to refrain from including any personal or sensitive information about their students when interacting with the chatbot. Additionally, the researchers discussed the potential implications of relying on AI-generated content in teaching, encouraging participants to use ChatGPT as a supplementary tool rather than a replacement for their own expertise and judgment. Throughout the workshop, participants had the opportunity to ask questions.

Later, the researchers approached the teachers offline in their institutions to articulate the conditions and terms of the research one more time. Additionally, the researchers brought their notebooks and ensured each teacher could actually interact with the chatbot. Shortly after the intervention concluded, proficiency in employing ChatGPT was measured again. Additionally, a self-reflection tool was distributed to the teachers. All participants provided written informed consent. More details on the study sequence can be found in

Figure 1.

As for past related works, Marzuki et al. [

41] acknowledged several constraints in their study, notably that the EFL teachers who took part were already familiar with and actively encouraging the use of AI tools before the research began. This pre-existing favor could potentially skew the results, leading to a greater emphasis on positive experiences and attitudes in the findings. To accommodate this oversight, we made an effort to ensure that the sample included those who had no prior experience of active use of ChatGPT or similar GenAI products in their teaching. Ultimately, this was the case for six of the participants in this study.

3.2. Intervention

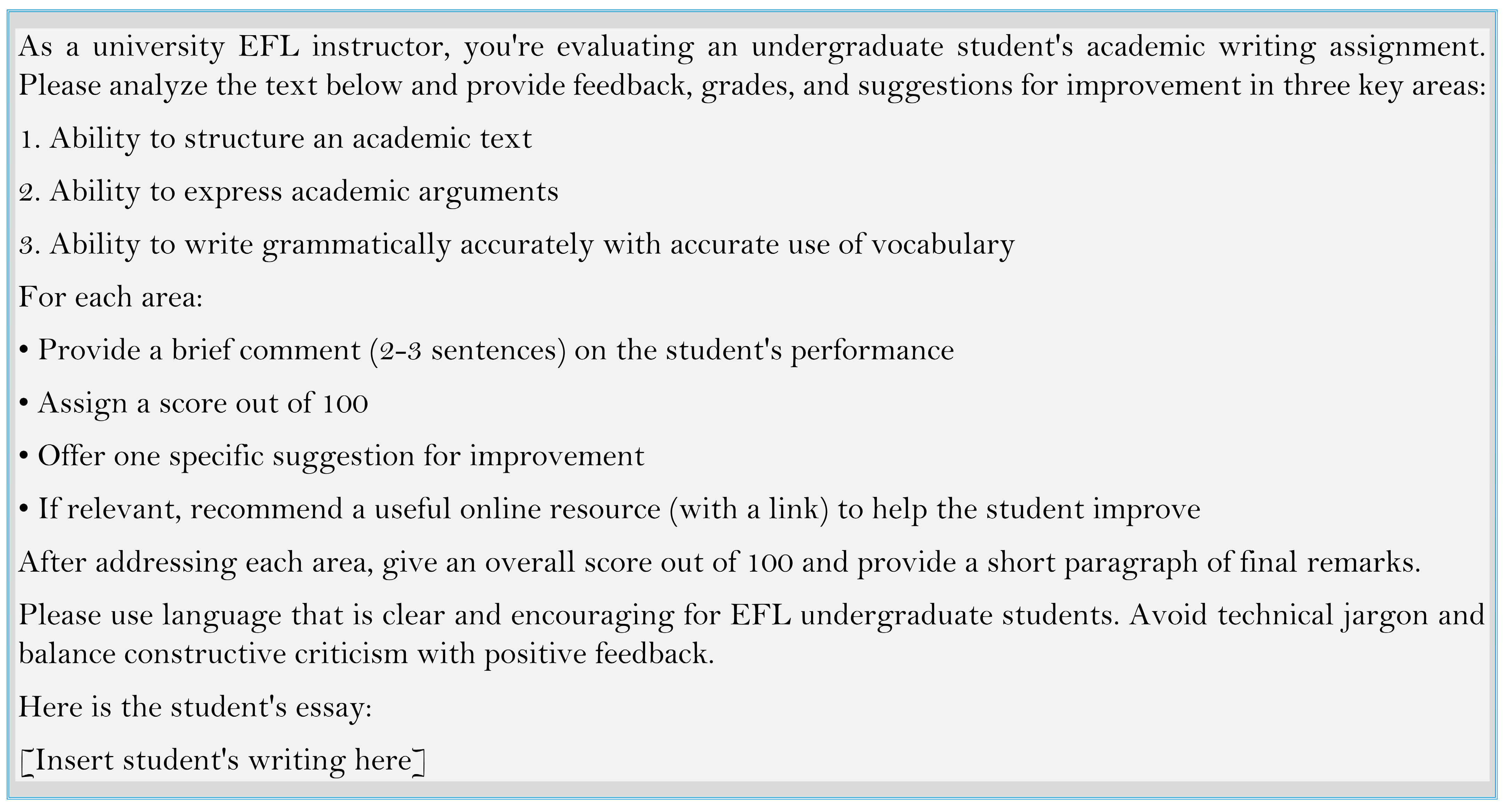

This was a researcher-guided prompt-driven ChatGPT integration in EFL teaching. The researchers iteratively engineered and piloted eight complex ChatGPT prompts, each addressing a specific goal in assisting EFL teaching. Two independent educational technology experts ensured each prompt’s potential to yield a relevant AI response. The prompts were digitally distributed to the teachers, with one prompt a week during the spring semester of the 2023–2024 academic year, for eight weeks, to experience ChatGPT’s capabilities in various teaching contexts. The teachers were instructed to adapt the prompt to their specific needs and context (e.g., the teacher had to indicate the topic their students struggled with when prompting ChatGPT to suggest explanations), and then apply the prompt in the ChatGPT entry bar, check if the chatbot’s response was really relevant, refine the response if required, and integrate the final output into their teaching practices during the same week, e.g., by adding the generated explanations on a topic through in-class exercises. One of the prompts can be found in

Figure 2. There was also a weekly reminder to effectuate the scenario. The prompts were employed in this intervention as follows:

Week 1. Activity: Crafting a lesson plan aligned with the 5E framework. Summary: The teacher inputs their lesson topic and educational objectives. ChatGPT proposes a structured lesson plan that includes content ideas, relevant sources, and a sequence of activities following the 5E (engage, explore, explain, elaborate, and evaluate) instructional framework (for a review on the 5E model, see [

42]).

Week 2. Activity: Generating explanations. Summary: The teacher specifies a concept or grammar point their students struggle with. ChatGPT provides concise explanations, incorporating authentic examples and analogies to help clarify the topic for students.

Week 3. Activity: Creating a targeted vocabulary list. Summary: The teacher provides a text excerpt, listening script, or topic along with context of the lesson and students’ English proficiency. ChatGPT suggests a list of key vocabulary items, including definitions, examples, and pronunciation.

Week 4. Activity: Designing a reading comprehension worksheet. Summary: The teacher inputs a reading passage and proficiency level. ChatGPT generates a worksheet with a mix of literal (recalling specific details in the text), inferential (making deductions by interpreting the meaning that is implicit in the text), and evaluative (making personal judgments) questions to examine students’ understanding.

Week 5. Activity: Integrating technology into EFL teaching. Summary: The teacher inputs the desired teaching outcomes and the technology of interest. ChatGPT proposes creative ways to incorporate technology into the classroom, recommending specific tools and resources that align with educational goals.

Week 6. Activity: Composing a diagnostic quiz. Summary: The teacher indicates the language skills and areas to assess. ChatGPT builds a quiz with a variety of question types (e.g., multiple choice, fill in the blanks, short answer) to evaluate students’ understanding and identify areas for additional support.

Week 7. Activity: Assessing a writing assignment. Summary: The teacher uploads a student’s writing. ChatGPT generates constructive feedback, rates the writing, and provides suggestions for improvement.

Week 8. Activity: Designing a speaking activity. Summary: The teacher inputs the speaking skill focus (e.g., fluency) and topic. ChatGPT generates an engaging speaking activity that promotes interaction and practice, including necessary materials, instructions, and possible variations for differentiation.

3.3. Measurement

3.3.1. ChatGPT’s Integration Proficiency

The researchers designed a ChatGPT Integration Proficiency Assessment (CIPA) tailored to evaluate EFL teachers’ abilities to integrate ChatGPT in a pedagogically effective and content-relevant manner, conforming to three technology-related dimensions of the TPACK model (

Table 1). Specifically, this test comprises three subscales focusing on a practical application of Technological Content Knowledge (TCK), Technological Pedagogical Knowledge (TPK), and the integrated construct (TPACK) in the context of incorporating ChatGPT into EFL teaching. TCK evaluates how well teachers can integrate ChatGPT into specific curriculum content and address specific content areas (e.g., grammar or vocabulary). TPK focuses on teachers’ understanding of how ChatGPT can be used to facilitate different pedagogical strategies and classroom practices. Finally, the TPACK subscale examines teachers’ mastery to combine EFL content, pedagogical strategies, and ChatGPT’s capabilities to create meaningful and effective learning experiences. The CIPA was inspired by the case of constructing an objective TPACK-based assessment by von Kotzebue [

43].

Each subscale consists of three open-ended items designed to elicit detailed responses, totaling nine items. Each of the three subscales was operationalized by summing the scores of the three individual items, each ranging from 0 to 2 points, thereby creating a possible composite score of 0 to 6 for each subscale. The total assessment score was derived by summing the scores across all three subscales, with a possible range of 0 to 18. To ensure more reliable scoring, a consensus scoring approach was employed, where two raters independently scored each response, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion to obtain the reported scores on the CIPA. Inter-rater reliability was calculated using Cohen’s kappa, which yielded a strong agreement level (κ > 0.80) for all dimensions.

The tasks posed in the test challenged the teachers to synthesize their knowledge and skills gained from the intervention and demonstrate a more advanced understanding of how to employ ChatGPT as a teaching facilitator compared to the level required to complete the experimental missions where the participants were provided with ready-made prompts. In other words, the CIPA tests the ability to apply the “baggage” of experience obtained during the intervention to novel, more complex teaching scenarios. That high bar was critical in order to isolate the intervention effect from the ChatGPT use competence that teachers could possess independent from what the researchers organized. The CIPA was piloted among six EFL educators beyond the final sample to ensure the instrument’s face validity, unambiguity, and feasibility. The pilot testing phase provided valuable feedback to refine the items and confirm that the test effectively measures the intended constructs. Feedback was collected regarding the clarity of questions, the relevance of the scenarios to real teaching contexts, and the appropriateness of the scoring criteria. This feedback led to several adjustments in the wording of items for clarity and the refinement of the scoring rubric to better differentiate between levels of proficiency.

For each item, a three-level scoring system was used: (0) no approach or an incorrect approach is described/the use of ChatGPT is not mentioned or not clearly explained; (1) an appropriate approach using ChatGPT is described, but lacks detail or clarity; and (2) a detailed and clear approach using ChatGPT is described.

3.3.2. Participants’ Reflection

Post-test, teachers completed an online questionnaire comprising three open-ended questions designed to capture their perceptions regarding the use of ChatGPT in their teaching practices over the eight-week intervention, as well as insights regarding the benefits, drawbacks, and promises of the chatbot. The questions are as follows: (1) In your view, what distinctive advantages has ChatGPT brought to your English language teaching approach? (2) What obstacles or constraints have you encountered while integrating ChatGPT into your teaching? (3) To your mind, how might ChatGPT potentially transform the field of teaching English in the years to come?

3.4. Data Analysis

3.4.1. Quantitative Analysis

To assess the difference between the pre-test and post-test scores on the CIPA, a series of matched-pair analyses were performed using JMP 17 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A matched-pair analysis was chosen to account for the within-subject design, where each teacher’s performance before and after the intervention was compared. This method is particularly suitable given the small sample size, as it increases statistical power by decreasing variation in the outcome within pairs [

44]. However, it is acknowledged that the small sample size increases the risk of Type II errors, where real differences might not be detected. Prior to conducting the analyses, the assumption of normality was examined via the Shapiro–Wilk test. The conventional alpha level of 0.05 was adjusted to the number of comparisons (four) to reduce the likelihood of incorrectly rejecting the null hypothesis (Type I error) due to multiple comparisons. Therefore, a difference was accepted as significant at a

p-value below 0.0125.

3.4.2. Qualitative Analysis

Initially, an inductive coding scheme was planned to be applied to the questionnaire data. But in mid-March 2024, a high-quality paper [

45] emerged reporting viewpoints of 46 English language teachers on utilizing ChatGPT in English language teaching. Upon consulting the publication, the researchers decided to orientate toward the deductive coding of the data. Specifically, three themes employed in [

45] for their qualitative analysis were derived, namely opportunities for integrating ChatGPT into EFL teaching, challenges in adopting ChatGPT for EFL teaching, and the promises of ChatGPT in EFL education. These themes comprised an a priori coding framework, which was used in the analysis presented herein. Having collected responses to the questionnaire items, the assistants read the text and independently tagged the obtained text data within the pre-imposed coding frame. Given the participants’ relatively brief responses and small sample, the data were analyzed using manual coding techniques. As a further step, each coder assigned a summary of the key findings to each of the three constructs. Finally, the analysts critically inspected each other’s coding. As a result, a consensus list of major insights falling within the themes was jointly synthesized.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Findings

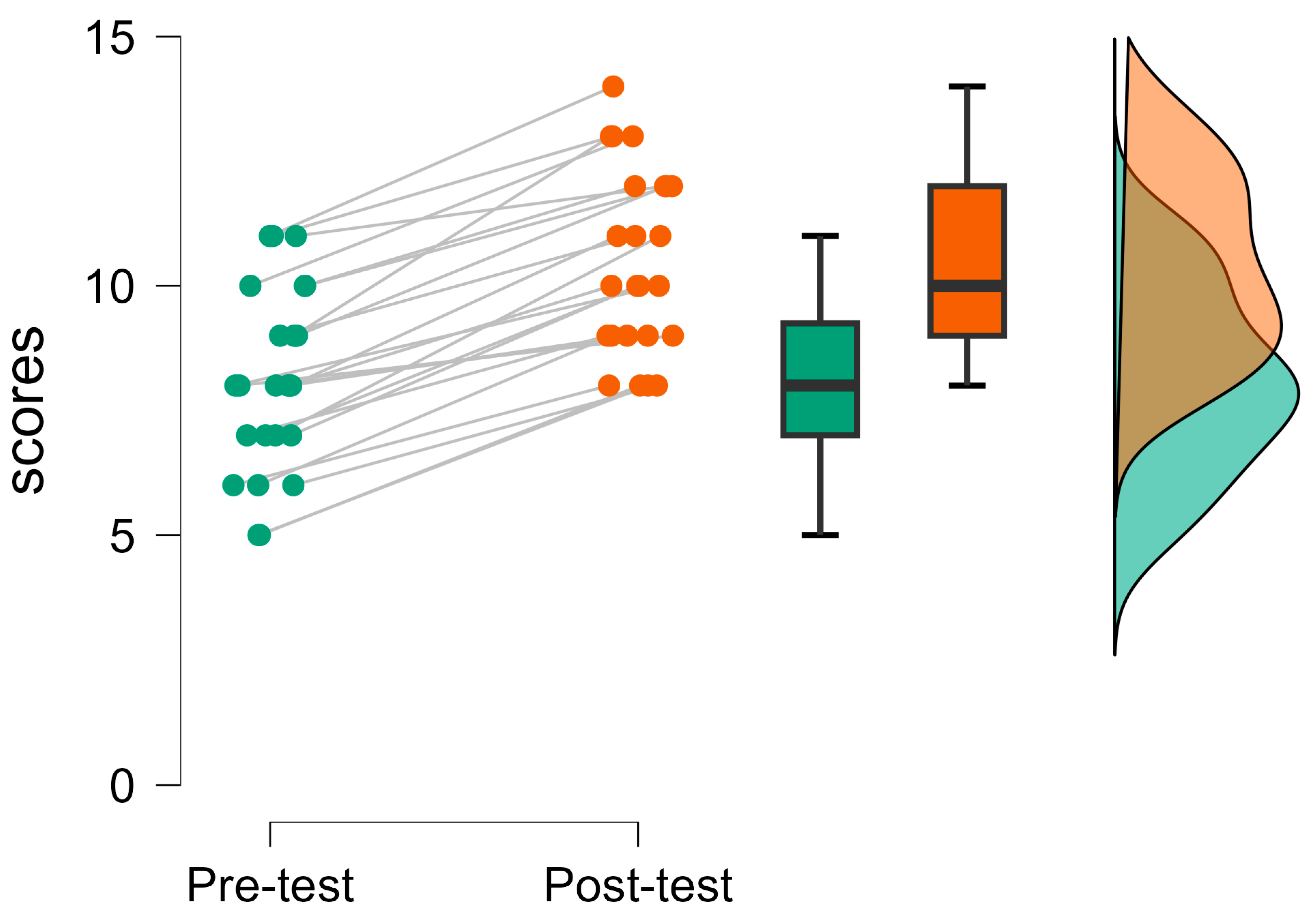

The first research question was intended to investigate the effect of the guided experimental implementation on EFL teachers’ mastery of infusing ChatGPT into their instructional practices. Descriptive and inferential statistics can be found in

Table 2. The matched-pair analysis conducted on the pre- and post-test CIPA results across all three subscales and the overall assessment revealed improvements in the teachers’ scores following the eight-week intervention.

The

p-values for all comparisons were less than the calibrated alpha threshold of 0.0125, indicating statistically significant differences between the baseline and post-evaluation. Individual total scores on the CIPA along with corresponding boxplots and a density plot are depicted in

Figure 3.

4.2. Qualitative Findings

The second research question sought to explore teachers’ perspectives toward their experience in the AI-driven journey and the perceived promises of ChatGPT. This section presents the findings from the open-ended questionnaire responses regarding the advantages, barriers, and prospects of integrating ChatGPT into EFL teaching.

Table 3 summarizes the key qualitative findings coded under the three predetermined themes.

4.2.1. Theme 1: Benefits of ChatGPT Use in EFL Teaching

The EFL teachers in this study overwhelmingly acknowledged the benefits of using ChatGPT in their teaching practices over the intervention period. One of the most reported opportunities that ChatGPT brought to their English language teaching practices was the chatbot’s creativeness. As one participant expressed, “There were moments when ChatGPT came up with such creative explanations and lesson activities that I was genuinely surprised. These were ideas that would have never crossed my mind. It has quite expanded my teaching repertoire”. Another teacher echoed this sentiment, stating the following: “The study organizers told us that we could ask ChatGPT to illuminate a phenomenon through metaphors or as if one were 5 years old. When I tried these techniques, I was impressed by how creative it can be to explain things to students”.

One more ChatGPT asset that the respondents appreciated was the automated assessment feature. The ability to partially robotize writing assessments was seen as a valuable reduction in cognitive load, making it easier for teachers to manage larger classes and provide timely feedback. A participant shared the following: “Having ChatGPT as an assistant made it psychologically easier for me to start checking essays. Even though I realized that I could not rely on the technology completely, just the fact that I could delegate some of the workload to it made the grading process less daunting”. Another teacher elaborated on this point by remarking the following: “The chatbot graded assignments first before I dove in, and this can be compared to a roadmap of what issues to look for”.

Moreover, the cost-free nature of ChatGPT was highlighted as a noteworthy advantage for educators. One teacher put it as follows: “I used to occasionally buy ready-made lesson plans and worksheets from abroad teachers on an English-language website, but it is unlikely to be needed anymore”. This evidence supports the decision to employ the no-subscription version of ChatGPT 3.5 rather than the paywalled 4.0 version in the intervention.

Additionally, some participants compared ChatGPT to established EFL tools like mobile apps and pointed out that ChatGPT had an edge in terms of practicality. For instance, one participant noted the following: “While Cambridge’s Write & Improve software (

https://www.cambridgeenglish.org/learning-english/free-resources/write-and-improve/ (accessed on 10 July 2024)) is a more proven and credible instrument than ChatGPT, it just scores the inputted writing on a scale from zero to five, without explanations on what’s wrong in the text and what are the user’s areas of development. Conversely, ChatGPT provides constructive feedback and suggestions for improvement, which is more helpful for both teachers and students”.

4.2.2. Theme 2: Challenges in ChatGPT Use in EFL Teaching

Despite the positive experiences, participants also pinpointed several challenges in the adoption of the conversational agent for their EFL teaching routine. It is quite expectable that one of the most mentioned hurdles within this theme was the need for thorough verification and customization of ChatGPT-generated content to ensure accuracy and relevance. This sentiment is exemplified particularly by the following case one respondent set out: “When composing a vocabulary list, ChatGPT sometimes included words that were not really relevant to my students’ proficiency level, requiring me to edit the list”. Another participant reflected the following: “It was a bit frustrating to have to double-check constantly what ChatGPT produced, even though I was aware of this specific limitation of AI before the experiment”.

The teachers also suffered from the need to manually convert hand-written text to typed text for input into ChatGPT due to software limitations, which was somewhat a pain point. As one informant described, “At the introductory workshop, we were advised to use handwriting-to-text tools like Transkribus to address the issue. However, these services sometimes failed to recognize or misrecognized hand-written fragments, requiring manual typing. This added an extra step to my workflow”.

Finally, some teachers complained that ChatGPT tended to regurgitate the same ideas in different wording, which limited its originality and usefulness. “I found that when subject of the prompt was non-trivial, the chatbot ended up in rephrasing a few same thoughts and scenarios, which is not very helpful,” commented a participant. Similar disappointment was indicated by another respondent: “It made me realize that the technology still has limitations when it comes to truly novel and unique ideation. It lacked the nuance I was hoping for”.

4.2.3. Theme 3: Promises of ChatGPT Use in EFL Teaching

The teachers were optimistic about the potential of ChatGPT and its future iterations in EFL education, particularly with the recent advent of ChatGPT 4o. This newer version offers the option to attach audios, videos, pictures, and documents to the prompt entry. The participants had no opportunity to use this novelty during the intervention as it was released in mid-May, shortly after the study’s conclusion. Overall, the research partakers anticipated that the new function of attaching files to the input box will open up new avenues for EFL teaching. Specifically, they placed a lot of hope in the enhanced capabilities of ChatGPT 4o for automated assessment thanks to the multimodal input. As one teacher speculated, “If the recent ChatGPT really affords recognizing images appropriately, then no need to type anymore. We can just paste a prompt, attach a photo of a student’s written work, and yield detailed feedback from the chatbot”.

Furthermore, the teachers saw potential in receiving AI-powered feedback on various media rather than text only. One teacher raised the question of whether ChatGPT could handle complex assessments. They pondered the following: “To my knowledge, when measuring students’ oral proficiency, it is common to use software like PRAAT to compute specific variables, such as the number of voice breaks in a speaking sample. It is unclear yet whether the new ChatGPT will be able to tackle things like that. Well, it is interesting to find out empirically in the future”.

Finally, some of the questionnaire completers envisioned new avenues for lesson planning. One informant explained the following: “If the app functions as intended, a teacher will be able to upload a page from a textbook and receive a customized lesson plan or any other requested material”. Thus, GenAI could automate various facets of teaching, from lesson planning to analyzing homework assignments and language test records.

5. Discussion

The primary purpose of this investigation was to explore the influence of a structured, prompt-driven ChatGPT implementation on EFL teachers’ proficiency in employing the chatbot within a professional development context, as well as their perceptions of its aptness and future potential in EFL education. The outcomes of this study illuminate a rather meaningful role of ChatGPT in adding to English teachers’ AI literacy. However, the practical significance of the teachers’ enhancement should be contextualized. The average pre- to post-test increase in the total ChatGPT performance score was about two points, indicating that the participants, on average, improved their responses on approximately two items across all subscales compared to the pre-assessment. This gain, while statistically discernable, is modest in practical terms. The underlying rationale for this phenomenon may be attributed to the intricate nature of the evaluation tool. Specifically, it necessitates a sophisticated proficiency in leveraging generative AI, including the ability to formulate nuanced queries, interpret generated outputs, refine them, and subsequently deploy the resultant products in teaching. Perhaps the duration of the intervention was insufficient for educators to acquire this level of expertise. Nonetheless, it is commendable that the CIPA has such a high ceiling, indicating its potential for continued application as a metric of teachers’ AI literacy, whether in the context of extended iterations of the experimental protocol described in this study or in alternative methodologies and disciplines.

However, even a moderate gain is an encouraging result considering the relatively short duration of the intervention. This implies a promising impact of the guided exposure to AI-powered assistants on teachers’ comprehension of how to properly leverage these technologies in their teaching practices. Moreover, the results suggest that ChatGPT has the potential to become a valuable asset in EFL education, offering benefits such as creative lesson planning, automated assessments, and personalized learning experiences.

The observed progress in teachers’ ChatGPT-related proficiency, as evidenced by the CIPA scores, can be attributed to several factors. First, the intervention’s design, which involved weekly engagement with the generative system, provided consistent, hands-on experience with the language model. This regular interaction likely facilitated the development of practical skills and confidence in using ChatGPT. Secondly, the prompts used in this study were meticulously crafted by the researchers and were not available on the Internet. The prompts were intended to elicit high-quality AI responses, creating an experimental condition that surpasses the conventional scenario where teachers might resort to brief, self-constructed prompts. This approach ensured that participants were exposed to the full potential of ChatGPT, thereby accelerating their learning curve and fostering a deeper understanding of its capabilities. The eight-week program could improve the measured TPACK dimensions by providing teachers with opportunities to practice using ChatGPT in various instructional contexts, thereby enhancing their technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge and the intersections among these facets. It is probable that the prompts were instrumental in enhancing these dimensions by encouraging teachers to experiment with ChatGPT’s capabilities and adapt them to their needs. Iterative practice with these prompts could help teachers become more adept at leveraging ChatGPT for teaching strategies.

6. Limitations

Despite its contributions, this study has limitations that should be acknowledged. The sample size was relatively small and geographically limited, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the duration of the intervention may not fully capture the long-term effects or sustainability of the observed improvements. The study also did not include a control group, which limits our ability to attribute the observed changes solely to the intervention. Concerning the limitations of the GenAI technology, in their study, Lee and Zhai [

46] noted that pre-service teachers were hesitant to incorporate ChatGPT into science education given the model’s training data cutoff in September 2021, which could result in the provision of outdated or erroneous information. While this limitation is less critical in English language teaching–learning, where factual accuracy is less paramount, it underscores the importance of carefully considering the context and potential biases of GenAI tools when deploying them for educational ends. One specific limitation of our study is the absence of prior empirical research on GenAI in educational settings to inform our design and execution. This constraint may have introduced unforeseen biases that we may not be aware of. Nevertheless, this limitation also confers a unique contribution to our study, positioning it as a foundational reference point for future experimentations.

7. Future Research

This intervention could potentially be more effective with longer implementation periods or with additional support mechanisms. As a line of future research, studies with larger, more diverse samples and control groups would enhance the robustness of the findings. Future studies can investigate the effectiveness of ChatGPT and its new features in EFL teaching and explore ways to overcome the challenges identified in this study. Additionally, evaluating the efficacy of different prompt types and their impacts on specific aspects of EFL teaching would be valuable. Finally, future research should explore the long-term impact of ChatGPT integration on teaching practices and student outcomes.

8. Conclusions and Implications

The findings presented here favor the viability of the AI integration approach for L2 teaching practices. While challenges exist, the potential benefits of AI in EFL education are apparent. The quantitative analysis revealed that, following the eight-week intervention, significant improvements were observed in the teachers’ mastery of ChatGPT. The qualitative analysis provided deeper insights into the teachers’ perspectives on the benefits, challenges, and future prospects of using ChatGPT in EFL teaching. The teachers recognized the chatbot’s creativity and automated assessment features as valuable assets that enriched their instructional repertoire and alleviated their cognitive load. However, they also identified downsides of the technology, particularly the need for constant verification of ChatGPT-generated content. Looking forward, the educators expressed optimism about the potential of future ChatGPT iterations, particularly the newly introduced multimodal capabilities, to further streamline and enhance EFL teaching. This optimism suggests a growing acceptance of AI-driven tools in the educational landscape, provided that the tools continue to evolve in ways that address the current limitations.

This study contributes to both research and practice in the field of educational technology and L2 teaching. It provides empirical evidence of the effectiveness of a structured approach to integrating GenAI tools in teachers’ professional development. Furthermore, it offers insights into the practical applications and challenges of using ChatGPT in EFL contexts, filling a gap in the literature. Unfortunately, a comparison of the findings reported here to similar studies is hampered by the underrepresentation of research related to in-service teacher training on professional GenAI usage, especially those adopting quantitative approaches rather than capturing perceptions exclusively. Moreover, existing studies on the topic, such as [

47], are generally limited by the self-reported nature of the outcome variables.

Based on the findings, it is recommended that EFL teacher training programs encompass guided GenAI integration modules. Educational institutions should provide ongoing support and resources for teachers to experiment with AI tools like ChatGPT in their settings. We also propose that teachers start with carefully designed prompts when using generative models, gradually developing their skills in prompt engineering. However, practitioners should remain critical of chatbots’ responses and double-check the generated content for accuracy and cogency. As AI continues to evolve, ongoing research and professional development will be crucial in harnessing its power to improve language teaching and learning outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.U. and R.K.; Methodology, G.U.; Supervision, R.K.; Data curation, A.K. and G.K.; Formal analysis, R.K., A.A. and A.K.; Writing—original draft, G.U., R.K. and G.K.; Writing—review & editing, A.A. and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University (09-073/01.0, 12 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings is available on request from the corresponding author upon rea-sonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Oliva, H.A.; Pérez-Morán, G.; Epifanía-Huerta, A.; Temoche-Palacios, L.; Iparraguirre-Villanueva, O. Critical thinking and digital competence in college students: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Eng. Pedag. 2024, 14, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolpe, K.; Hallström, J. Artificial intelligence literacy for technology education. Comput. Educ. Open 2024, 6, 100159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashish, E.A.; Alnajjar, H. Digital proficiency: Assessing knowledge, attitudes, and skills in digital transformation, health literacy, and artificial intelligence among university nursing students. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Almusharraf, N. Digital learning demand and applicability of quality 4.0 for future education: A systematic review. Int. J. Eng. Pedag. 2024, 14, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, E.; Zhai, X. Fine-tuning ChatGPT for automatic scoring. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, 100210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, A.R.; Mosalli, Z. The role of twenty-first century digital competence in shaping pre-service teacher language teachers’ twenty-first century digital skills: The Partial Least Square Modeling Approach (PLS-SEM). J. Comput. Educ. 2024. early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.K.; Ahmad, Z.; Ismailov, M.; Sanusi, I.T. What are artificial intelligence literacy and competency? A comprehensive framework to support them. Comput. Educ. Open 2024, 6, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khennouche, F.; Elmir, Y.; Himeur, Y.; Djebari, N.; Amira, A. Revolutionizing generative pre-traineds: Insights and challenges in deploying ChatGPT and generative chatbots for FAQs. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 246, 123224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannuru, N.R.; Shahriar, S.; Teel, Z.A.; Wang, T.; Lund, B.D.; Tijani, S.; Pohboon, C.O.; Agbaji, D.; Alhassan, J.; Galley, J.; et al. Artificial intelligence in developing countries: The impact of generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies for development. Inf. Dev. 2023. early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamalai, N.; Rashid, R.A.; Hashmi, U.M.; Mohamed, M.; Alqaryouti, M.H.; Sadeq, A.E. Using chatbots for English language learning in higher education. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2023, 5, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behforouz, B.; Al Ghaithi, A. Investigating the effect of an interactive educational chatbot on reading comprehension skills. Int. J. Eng. Pedag. 2024, 14, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatwattana, P.; Yangthisarn, P.; Tabubpha, A. The educational recommendation system with artificial intelligence chatbot: A case study in Thailand. Int. J. Eng. Pedag. 2024, 14, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, P.; Peñalver, E.A.; Urbieta, A.S. Transnational higher education cultures and generative AI: A nominal group study for policy development in English medium instruction. J. Multicult. Educ. 2024, 18, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, L. Application of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GENAI) in language teaching and learning: A scoping literature review. Comput. Educ. Open 2024, 6, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, F.A.; Cruz-Bohorquez, J.M. Engineering education in the age of AI: Analysis of the impact of chatbots on learning in engineering. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, G.; Amzalag, M.; Shaked, N.; Zaguri, Y.; Kohen-Vacs, D.; Gal, E.; Zailer, G.; Barak-Medina, E. Strategies for integrating generative AI into higher education: Navigating challenges and leveraging opportunities. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzirides, A.O.; Zapata, G.; Kastania, N.P.; Saini, A.K.; Castro, V.; Ismael, S.A.R.; You, Y.; Santos, T.A.; Searsmith, D.; O’Brien, C. Combining human and artificial intelligence for enhanced AI literacy in higher education. Comput. Educ. Open 2024, 6, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özçelik, N.P.; Ekşi, G.Y. Cultivating writing skills: The role of ChatGPT as a learning assistant—A case study. Smart Learn. Environ. 2024, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, N.J.; Daniel, N.B.K. A systematic review of AI-powered chatbots in EFL speaking practice: Transforming language education. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, K.; Wu, X. ChatGPT as a CALL tool in language education: A study of hedonic motivation adoption models in English learning environments. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024. early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Hao, J.; Fauss, M.; Li, C. Detecting ChatGPT-generated essays in a large-scale writing assessment: Is there a bias against non-native English speakers? Comput. Educ. 2024, 217, 105070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memarian, B.; Doleck, T. ChatGPT in education: Methods, potentials, and limitations. Comput. Hum. Behav. Artif. Hum. 2023, 1, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, L.T.; Yousif, M.R.; Alnoori, N.A.J.; Majeed, B.H. The impact of artificial intelligence on computational thinking in education at university. Int. J. Eng. Pedag. 2024, 14, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. The application and challenges of ChatGPT in educational transformation: New demands for teachers’ roles. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayanwale, M.A.; Adelana, O.P.; Molefi, R.R.; Adeeko, O.; Ishola, A.M. Examining artificial intelligence literacy among pre-service teachers for future classrooms. Comput. Educ. Open 2024, 6, 100179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumi, D.; Noroozi, O. Developing early career teachers’ professional digital competence: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2023. early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorhouse, B.L.; Kohnke, L. The effects of generative AI on initial language teacher education: The perceptions of teacher educators. System 2024, 122, 103290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M.J. Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2006, 108, 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumann, A.; Schnebel, S.; Weitzel, H. Teaching biology lessons using digital technology: A contextualized mixed-methods study on pre-service biology teachers’ enacted TPACK. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.C.; Kim, C. Pedagogical competence analysis based on the TPACK model: Focus on VR-based survival swimming instructors. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nantha, C.; Siripongdee, K.; Siripongdee, S.; Pimdee, P.; Kantathanawat, T.; Boonsomchuae, K. Enhancing ICT literacy and achievement: A TPACK-based blended learning model for Thai business administration students. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kwon, K. Exploring the AI competencies of elementary school teachers in South Korea. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2023, 4, 100137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundi, M.; Sanusi, I.T.; Oyelere, S.S.; Ayere, M. Advancing AI education: Assessing Kenyan in-service teachers’ preparedness for integrating artificial intelligence in competence-based curriculum. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2024, 14, 100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D.T.K.; Leung, J.K.L.; Su, J.; Ng, R.C.W.; Chu, S.K.W. Teachers’ AI digital competencies and twenty-first century skills in the post-pandemic world. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2023, 71, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Battaglia, F.; Udaiyar, A.; Fooks, A.; Terlecky, S.R. An explorative assessment of ChatGPT as an aid in medical education: Use it with caution. Med. Teach. 2023, 46, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X. Exploring EFL university teachers’ beliefs in integrating ChatGPT and other large language models in language education: A study in China. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2024, 44, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.M. Exploring the potential of an AI-based Chatbot (ChatGPT) in enhancing English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teaching: Perceptions of EFL faculty members. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 3195–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Chen, Y.; Miao, J. Opportunities, challenges, and future directions of large language models, including ChatGPT in medical education: A systematic scoping review. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2024, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejeb, A.; Rejeb, K.; Appolloni, A.; Treiblmaier, H.; Iranmanesh, M. Exploring the impact of ChatGPT on education: A web mining and machine learning approach. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2024, 22, 100932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.; Park, H.; Looi, C. From hype to insight: Exploring ChatGPT’s early footprint in education via altmetrics and bibliometrics. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2024. early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzuki; Widiati, U.; Rusdin, D.; Darwin; Indrawati, I. The impact of AI writing tools on the content and organization of students’ writing: EFL teachers’ perspective. Cogent Educ. 2023, 10, 2236469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegegne, T.A.; Kelkay, A.D. Comparative study of using 5E learning cycle and the traditional teaching method in chemistry to improve student understanding of water concept: The case of primary school. Cogent Educ. 2023, 10, 2199634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Kotzebue, L. Two is better than one—Examining biology-specific TPACK and its T-dimensions from two angles. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2023, 55, 765–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzer, L.B.; Petersen, M.L.; Van Der Laan, M.J. Adaptive pair-matching in randomized trials with unbiased and efficient effect estimation. Stat. Med. 2014, 34, 999–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khresheh, M.H. Bridging technology and pedagogy from a global lens: Teachers’ perspectives on integrating ChatGPT in English language teaching. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, 100218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Zhai, X. Using ChatGPT for science learning: A study on pre-service teachers’ lesson planning. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2024, 17, 1683–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, A.E.; Shi, L.; Yang, H.; Choi, I. Enhancing teacher AI literacy and integration through different types of cases in teacher professional development. Comput. Educ. Open 2024, 6, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).