Centering Equity within Principal Preparation and Development: An Integrative Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the key issues and actions that have been considered or received attention in the equity-centered (re)design of preparation programs in relation to program vision, curriculum, pedagogy, and assessments?

- What examples or illustrations exist of such work?

Placing the United States Preparation System within an International Context

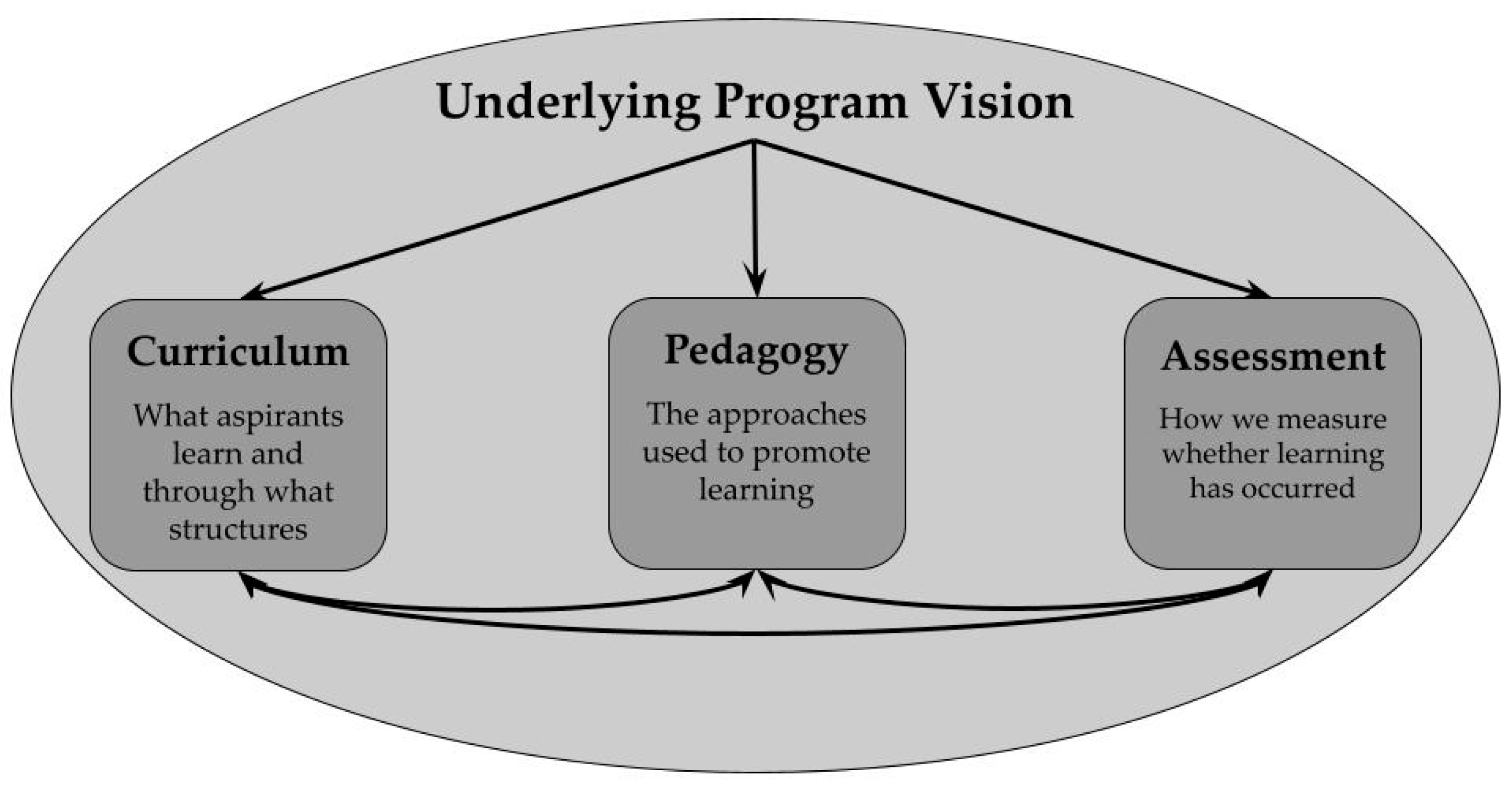

2. Conceptual Framing

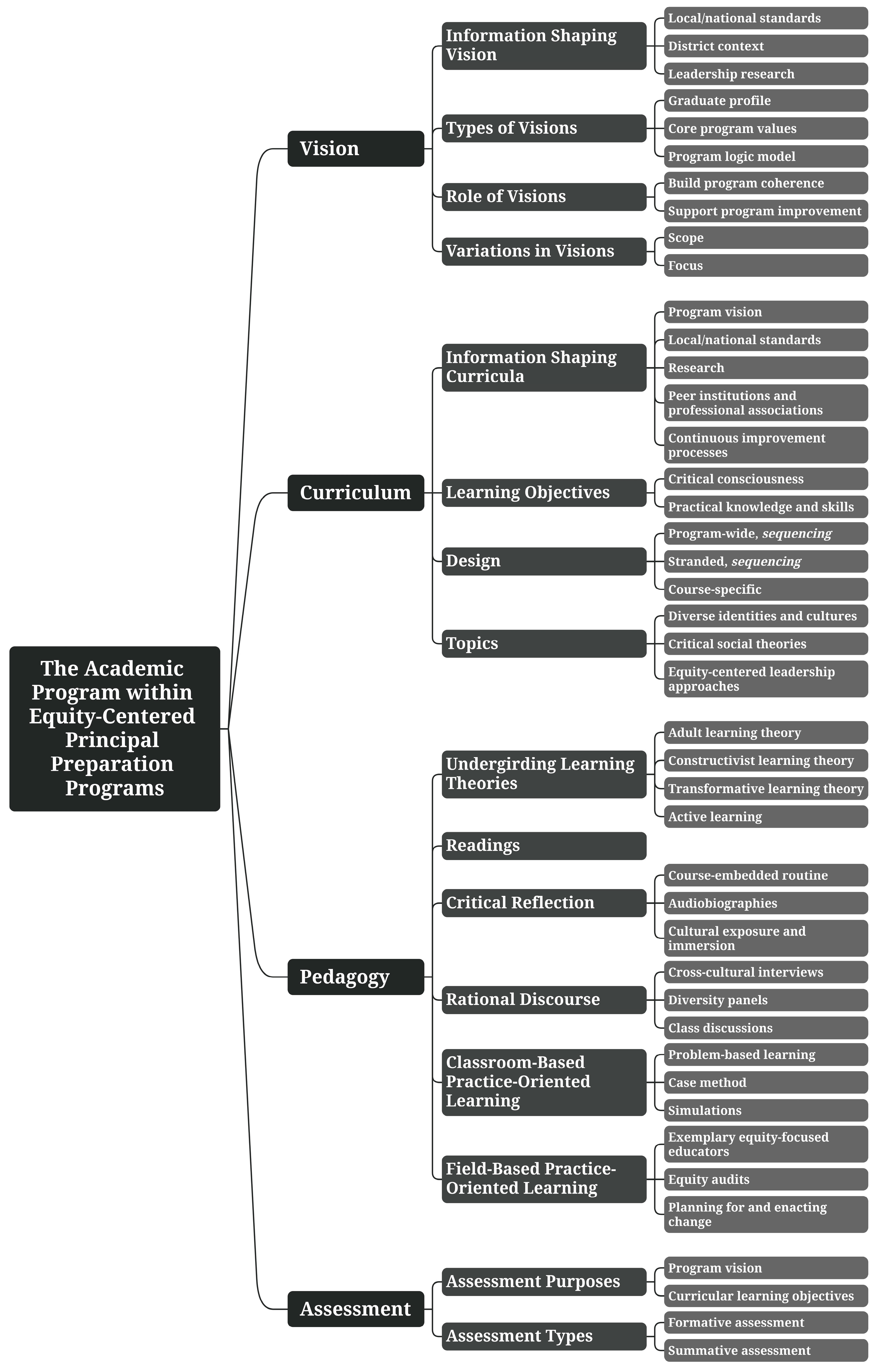

2.1. Program Vision

2.2. Curriculum

2.3. Pedagogy

2.4. Assessment

3. Methodology

3.1. Search Procedures

3.2. Analytic Procedures

3.3. State of the Literature

4. Findings

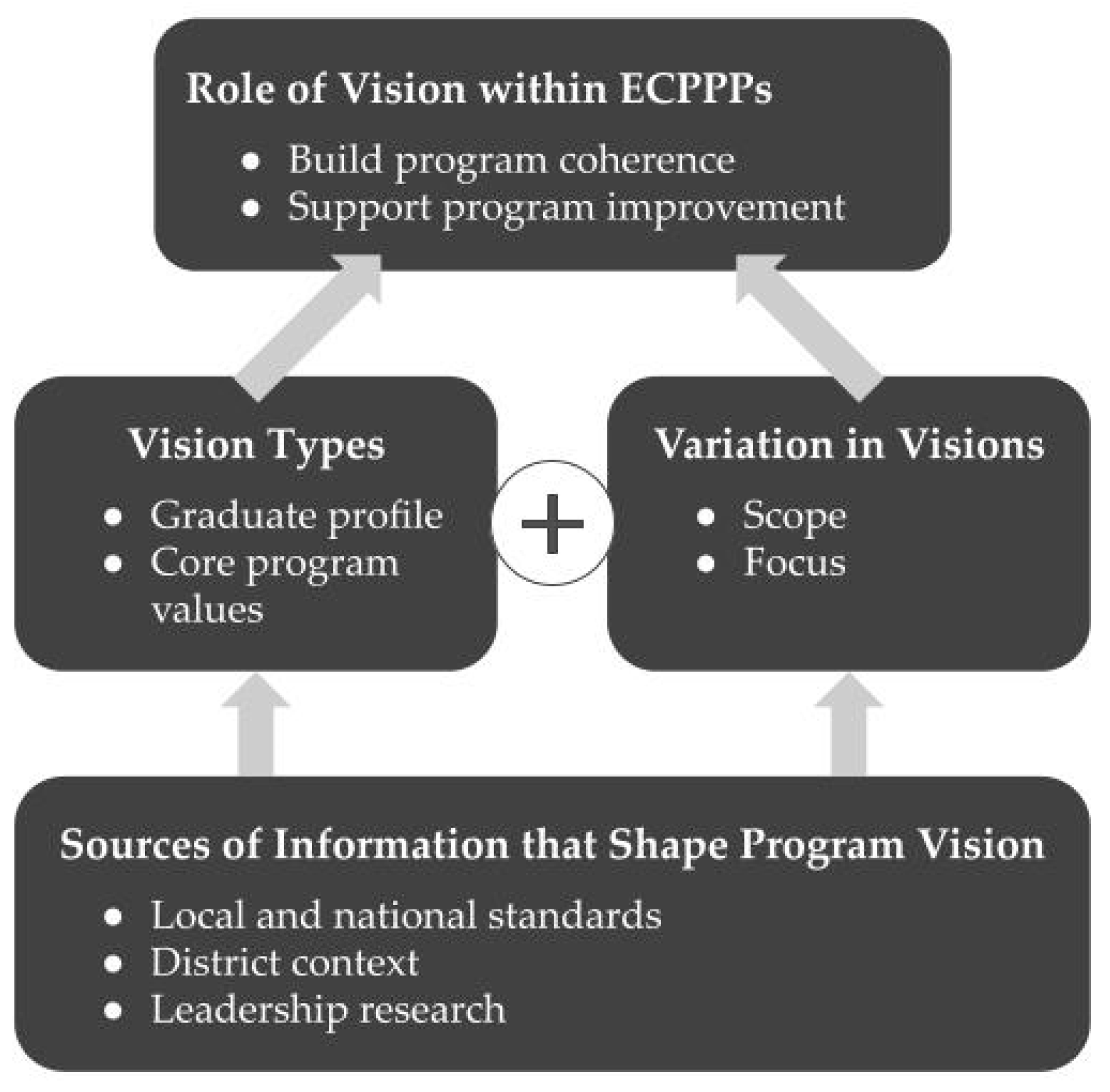

4.1. Program Vision

4.1.1. Sources of Information for Equity-Centered Program Visions

4.1.2. Types of Visions within ECPPPs

4.1.3. Role of Vision within ECPPPs

4.1.4. Variability in Equity-Centered Program Visions

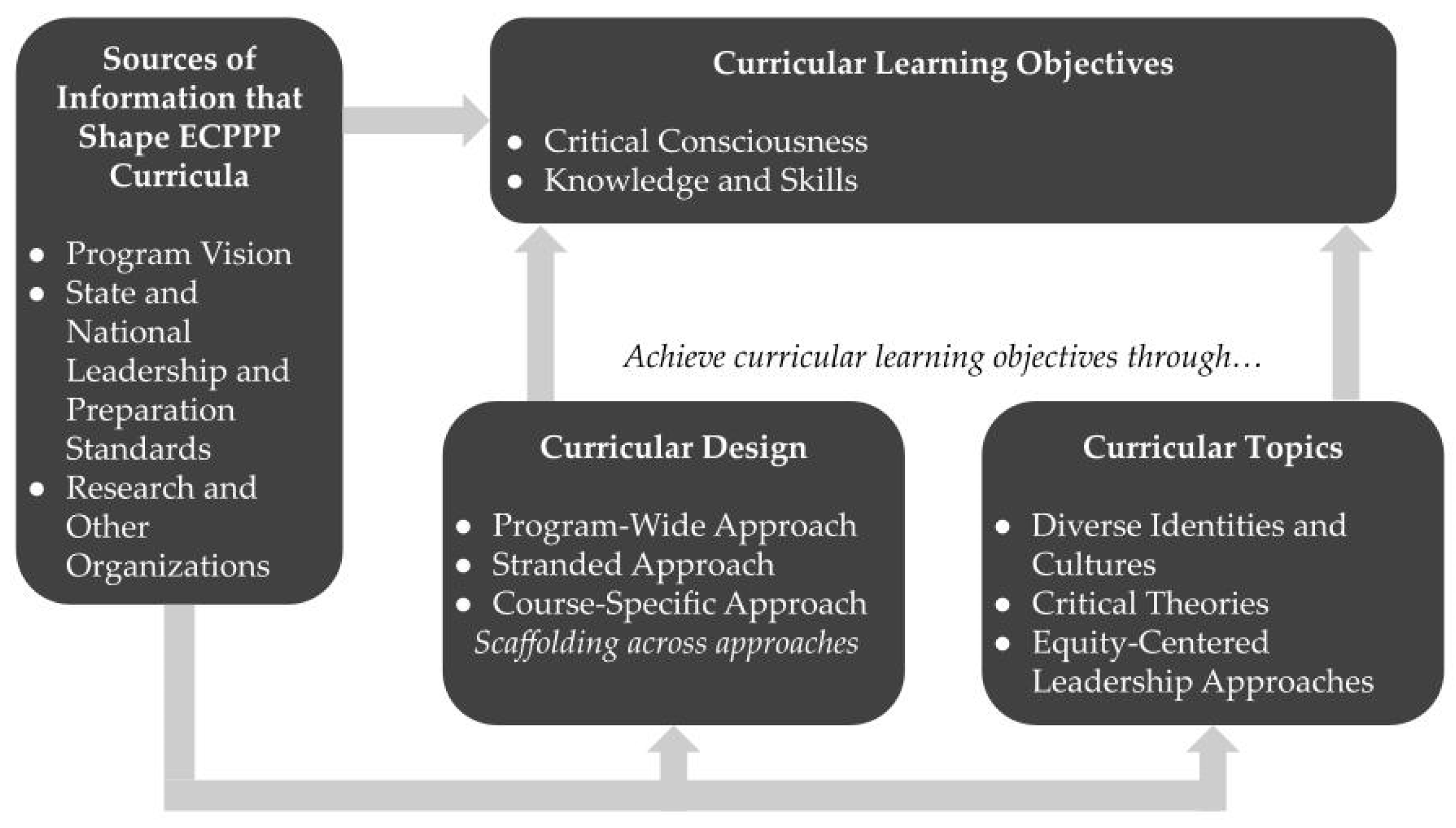

4.2. Curriculum

4.2.1. Sources of Information for Equity-Centered Program Curriculum

While this represents just one article’s perspective, our knowledge of the field highlights the fact that several of the authors writing about their efforts to strengthen program equity orientations participated in collaborative inquiry around this topic with peer institutions through grant-funded and/or professional networks (e.g., [18,40,75,97]).Engaging in collaborative inquiry and program redesign alongside peer institutional members of UCEA can be a powerful driver for organizational and programmatic improvement. For example, a program might identify an internal challenge within their recruitment efforts, program structure, curriculum, learning experiences, district partnerships, etc., and invite faculty colleagues from other institutions to visit and offer their expertise. In addition to having other faculty to provide feedback and support, programs may also visit peer programs with characteristics they would like to emulate.(p. 20)

4.2.2. Equity-Centered Curricular Learning Objectives

4.2.3. Equity-Centered Curricular Designs

Including these specific courses exploring equity does not necessitate that programs do not also infuse all courses with equity, but that these programs draw importance to deliberate attention to issues of equity within full courses.While the authors agree with Marshall (2004) that social justice should not be limited to discussion in one discrete course in a preparation program, it is logical to address social justice issues in our program’s required foundations course, which requires that students reflect upon history and theoretical perspectives of schooling within the context of their own cultural identity.(p. 3)

4.2.4. Equity-Centered Curricular Topics

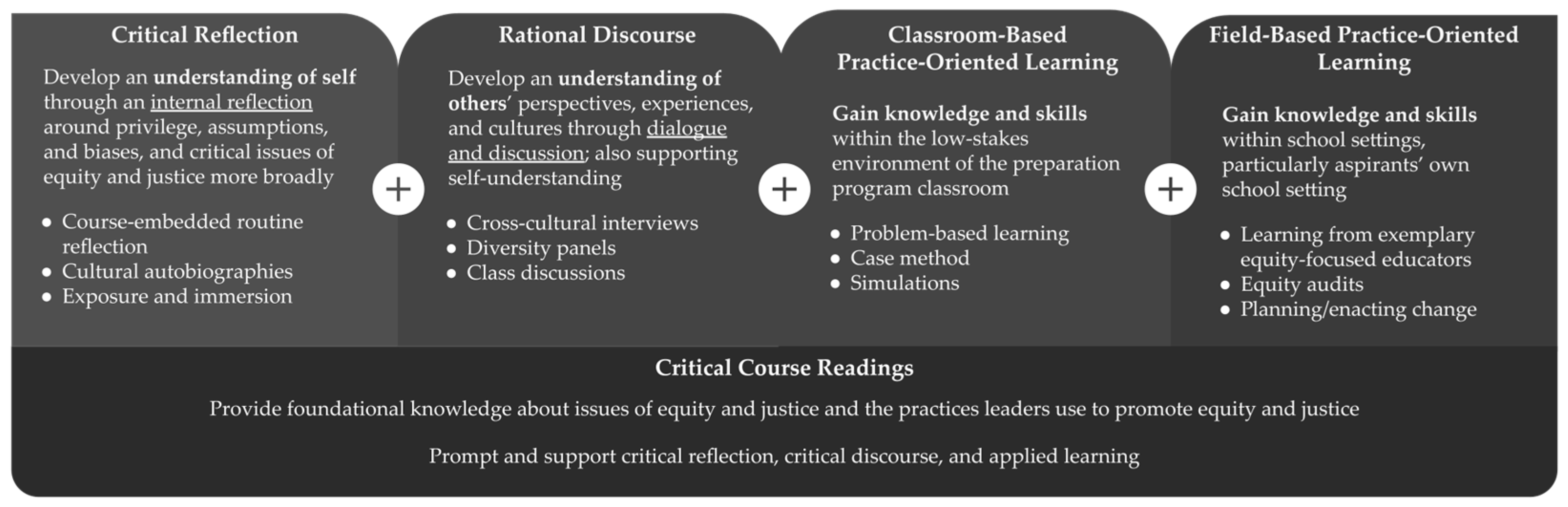

4.3. Pedagogy

4.3.1. Undergirding Learning Theories within ECPPPs

Within ECPPPs, PLEs can lead aspirants toward developing their critical consciousness, strengthening their ability to critically analyze equity-centered problems of practice within their own school contexts, and advance their self-efficacy as equity-centered school leaders [34].(1) they are authentic, meaningful, relevant, problem-finding activities; (2) they involve sensemaking around critical problems of practice; (3) they involve exploration, critique, and deconstruction from an equity perspective (for example, race, culture, language); (4) they require collaboration and interdependence; (5) they develop confidence in leadership; (6) they place both the professor and the student in a learning situation; (7) they empower learners and make them responsible for their own learning; (8) they shift the perspective from classroom to school, district, or state level; and (9) they have a reflective component.[63] (p. 445)

4.3.2. Equity-Centered Readings

4.3.3. Critical Reflection within ECPPPs

4.3.4. Rational Discourse within ECPPPs

It pushed my boundaries, forced me to go beyond what I am familiar with, helped me see my blind spots, tested the amount of fortitude that I had within myself, and made me have to stretch myself so thin I thought I was going to have to go into therapy just to debrief.(p. 727)

4.3.5. Classroom-Based Practice-Oriented Learning toward Equity

4.3.6. Field-Based Practice-Oriented Learning toward Equity

4.3.7. Interconnections amongst Pedagogical Approaches

4.4. Assessment

4.4.1. Assessment Purposes within ECPPPs

4.4.2. Assessment Types within ECPPPs

5. Conclusions

5.1. Implications for Preparation and Development

5.2. Implications for Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Citation | Study Type | Method | Focus of Leadership | Purpose of the Piece | Context | Examples of Impact if Empirical |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agosto et al., 2013 [122] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Literature Review: Qualitative metasynthesis | Culture-based/multicultural leadership | Understand how culture-based understandings of school leadership are visible in the principal preparation literature | N/A | N/A |

| Alford and Hendricks, 2018 [141] | Empirical | Qualitative: Focus groups, open-ended surveys, action research projects, course observations; all within one program | ELL students and also broadly historically marginalized students with a centering of college-going rates | Investigate key impactful features of a principal preparation program at a local university that partnered with a local district | Does not specify | Aspiring principals noted action research projects, cohort design, panel presentations by acting principals, and serving on data teams as key impactful features to their development as equity leaders. |

| Arzu et al., 2023 [35] | Descriptive | Qualitative: Descriptions of programs’ experiences and actions | Broad | Examine three programs’ experiences using the QM Principal Preparation Program Self-Study Toolkit | Three programs, one in East Texas and one in West Texas | N/A |

| Baecher et al., 2016 [87] | Empirical | Qualitative: Field notes during classroom workshop, online discussion board posts, questionnaire responses, completed observation tools | ELL students | Explore how a specific observation tool for ELL instruction, which used guided video analysis and live observation, was useful (or not) to the preparation of leaders who can support teachers in working with these students | City in the Northeast | The observation tool supported aspirants’ development toward supporting ELL instruction, such as by identifying key ELL teaching practices |

| Barakat et al., 2019 [103] | Empirical | Quantitative: Quantitative survey instrument with Likert-type scale items | Culturally competent leaders | Examine whether graduates of preparation programs across the U.S. had grown in their cultural competence from beginning to ending their programs | United States—several programs | Program graduates broadly had increased cultural competence, cultural beliefs and motivation, and cultural knowledge; they had not advanced in cultural skills |

| Barakat et al., 2021 [18] | Empirical | Mixed Method: Pre- and post-test Likert-type questionnaire to assess aspirants’ cultural competence; semi-structured focus groups with instructors and students; instructors’ formative assessment comments to aspirants | Culturally competent leaders | Examine changes in cultural beliefs, motivation, knowledge, skills, and competence of aspirants who have gone through a preparation program seeking to build these aspects | Southeast, large and diverse | Impactful program components provided by survey respondents centered the cross-curricular theme of cultural competence; students reported advancing their understandings of and attitudes about issues of justice via knowledge from the program; additionally, by learning from diverse cohort and professors; students’ communication skills and application of justice lens improved |

| Berkovich, 2017 [28] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Theoretical/conceptual essay | Social justice leadership | Explore social justice-related aspects of preparation program design | N/A | N/A |

| Billingsley et al., 2018 [151] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Theoretical/conceptual essay | Inclusive leadership for students with disabilities | Examine what effective inclusive school leadership would look like within the PSELs and provide recommendations and implications for preparation | N/A | N/A |

| Boske, 2012 [119] | Empirical | Qualitative: Interviews, written narratives, field notes | Social justice leadership | Examine the role of artmaking in the preparation of aspirant school leaders who can address issues of justice within schools | Texas | Artmaking was a valuable tool that allowed aspirants to build understandings and sensitivity to social justice issues and work |

| Boske, 2012a [152] | Empirical | Qualitative: Weekly reflections, field notes, course assignments | Social justice leadership | Investigate the use of artmaking within a social justice-oriented preparation class within one preparation program | Northeastern University | Artmaking allowed for aspirants to have space to consider issues of justice through critical reflection, critical reflections led to evolving beliefs and increased aspirants’ empathy, and aspirants reported their critical consciousness increased through the artmaking process |

| Brown, 2004 [24] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Theoretical/conceptual essay | Social justice leadership | Offer a model that could support the preparation of socially just school leaders using theoretical perspectives and pedagogical approaches | N/A | N/A |

| Brown, 2006 [42] | Empirical | Mixed Method: Pre- and post-test Likert-type questionnaire to assess aspirants’ dispositions; weekly reflective journal entries also collected and analyzed | Social justice leadership | Explore the effects of transformative andragogy [24] on leadership preparation for social justice | Large university in the Southeast | Aspirants increased in their awareness of and openness to issues of equity as a result of their participation in the transformative strategies, which included autobiographies, problem-based learning, case studies, cohort groups, reflective journals, cross-cultural interviews, life histories, diversity workshops, educational plunges, diversity panels, and activist assignments |

| Byrne-Jiménez and Borden, 2015 [36] | Descriptive | Quantitative: Use one question from a survey of UCEA preparation programs, describes one broad aspect of the state of preparation | Broad; diversity of leader pipeline | Provide an examination of diversity within UCEA educational leadership programs using the literature and survey questions | Does not specify | N/A |

| Byrne-Jiménez and Orr, 2013 [31] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Theoretical/conceptual essay | Social justice leadership | Propose a framework for social justice leadership preparation that addresses key challenges, best practices, and issues of recognition, redistribution, and reversal | N/A | N/A |

| Callahan et al., 2019 [88] | Descriptive | Qualitative narrative accounting of the program redesign process written by program faculty (no methods section) | Linguistic equity | Propose a framework for integrating linguistic equity into leadership preparation and describe efforts of one program that has integrated this framework | University of Texas Austin | N/A |

| Capper et al., 2006 [90] | Descriptive | Qualitative: Review of eight faculty members’ syllabi and related reading lists for courses including LGBTQ+ topics, as well as strategies used to integrate these topics | Leadership for LGBTQ+ students | Identify key strategies preparation program faculty might rely upon to advance aspirants’ ability to serve LGBTQ+ students within their schools | Does not specify | N/A |

| Capper et al., 2006a [30] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Literature Review: Review of 72 pieces of the literature | Social justice leadership | Provide a systematic review of the literature that identifies a key framework for conceptualizing the preparation of socially just school leaders | N/A | N/A |

| Carpenter and Diem, 2013 [43] | Empirical | Qualitative: Interviews with 6 professors teaching courses that include race in preparation programs, informal communications | Leadership and race consciousness | Examine the use of critical conversations around race within educational leadership preparation programs | Does not specify | Reflective writing exercises around issues of race, gender, and class led to aspirants’ developing closer relationships with cohort and growth in understandings; planning and scaffolding can support growth; using particular resources like Courageous Conversations can be impactful |

| Celoria, 2016 [104] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Theoretical/conceptual essay | Inclusive leadership but broadly defined as for all students (e.g., across race, language, disability) | Review the literature and leadership standards to provide insights related to the preparation of equity- and justice-centered, inclusive leaders | N/A | N/A |

| Clement and Young, 2022 [153] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Theoretical/conceptual essay | Broad; diversity of leader pipeline | Provide a brief introduction to issues in diversifying leadership pipelines ahead of a special issue | N/A | N/A |

| Clement et al., 2022 [74] | Empirical | Qualitative: Interviews with 26 senior faculty of diverse preparation programs across the U.S. | Broad; diversity of leader pipeline | Examine the characteristics of highly diverse principal preparation programs to identify key strategies these programs use to increase their diversity | Does not specify | Programs with stated aims related to equity/justice may be more likely to diversify their aspirant pool; supports contributed to more diverse aspirants joining the program, such as hybrid and other delivery structures, cohorts, and mentoring; work with partnerships allowed for developing diverse pipelines and placing aspirants within residencies, an attractor |

| DeMatthews et al., 2020 [72] | Empirical | Qualitative: Three interviews with each leader | Inclusion, students with disabilities | Examine the experiences of six preservice leaders who sought to create more inclusive schools for students with disabilities | West Texas | Aspirants felt prompted to learn more about special education and disability after engaging in self-reflection; class discussions influenced aspirants’ understandings of their role as advocates for students with disabilities; Crucial Conversations was an impactful and useful resource |

| Diem and Carpenter, 2012 [32] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Literature Review: Review of the literature across five most-frequently read journals by educational leadership professors | Race and anti-racist leadership | Examine the literature related to leadership preparation for leaders who can work in diverse settings, particularly as related to race | N/A | N/A |

| Diem et al., 2019 [85] | Empirical | Qualitative: Focus groups during aspirants’ first year and interviews during aspirants’ second year | Anti-racist leadership | Examine how aspirants in one preparation program developed anti-racist identities while working in a school choice district | Urban, Midwest | Conversations around race increased aspirants’ consciousness about race; critical self-reflection supported aspirants’ development around anti-racism |

| Evans, 2007 [37] | Descriptive | Qualitative: Use historical data such as biographies and the scholarly literature to examine a historic leadership preparation program | Social justice leadership | Explore facets of the Highlander Folk School and how these relate to preparation programs today | Tennessee, 1930s and beyond | N/A |

| Everson and Bussey, 2007 [111] | Descriptive | Qualitative narrative accounting of the program redesign process written by program faculty (no methods section) | Leadership for social justice | Describe how faculty members within one program sought to expand its orientation around social justice | Saint Louis University | N/A |

| Figueiredo-Brown et al., 2015 [116] | Empirical | Qualitative: Written reflections and overall reflections | Broad; diversity related to cultural, linguistic, class, gender, sexual orientation, religion | Investigate one preparation program’s emphasis on diversity throughout the internship experience | Eastern Carolina University | Broad—Interns engaged in the internship seminar found themselves challenged but also saw their eyes opened about issues of diversity through various speakers in their seminar |

| Fuller and Young, 2022 [154] | Descriptive | Quantitative: Use extant quantitative data to examine trends in the Texas leadership pipeline | Broad; diversity of leader pipeline | Understand how principal pipelines contribute to diversity in leadership aspirants, using Texas as an example. | Texas | N/A |

| Furman, 2012 [25] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Theoretical/conceptual essay | Social justice leadership | Explore the idea of social justice leadership as praxis and propose a conceptual framework that captures this idea | N/A | N/A |

| Garver and Maloney, 2020 [20] | Empirical | Qualitative: Discussions and experiences between two professors throughout the course development, vision statements written by aspirants, reflections, online written discussion and in-class discussions, key lesson takeaways, graphic organizers filled out in class | Equity-oriented leadership | Explore two professors’ development of one lesson in a principal preparation program that was meant to explore supervising for equity | Northeast | Providing structures such as guiding tools and scaffolded learning opportunities supported aspirants’ ability to develop skills to identify and respond to inequity within their schools, and the specific lesson utilized supported aspirants’ ability to conduct equity work |

| Genao, 2021 [123] | Descriptive | Qualitative narrative accounting of the program redesign process written by program faculty (no methods section) | Culturally responsive leadership | Describe efforts to include culturally responsive teaching and leading within one course across multiple semesters | Does not specify | N/A |

| Gooden and Dantley, 2012 [26] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Theoretical/conceptual essay | Anti-racist leadership | Advances a framework for educational leadership preparation that centers race, includes self-reflection, critical theory, prophetic and pragmatic edge, praxis, race language | N/A | N/A |

| Gooden and O‘Doherty, 2015 [45] | Empirical | Qualitative: Racial autobiographies created by students | Anti-racist leadership | Examine one program’s use of racial autobiographies and these autobiographies’ impact on aspirants’ racial awareness | Southwest | Racial autobiographies led to aspirants growing in their racial awareness and understandings, such as increasing acknowledgement of white privilege, which led to self-reflection and aspirants feeling more committed to anti-racist action |

| Gooden et al., 2018 [94] | Empirical | Qualitative: Interviews with eight aspirants within one program to examine how the program impacted their ability to engage in anti-racist leadership | Anti-racist leadership | Investigate the ways in which one program facilitates changes aspirants’ understandings of race and racism | Does not specify | Studying anti-racist leadership impacted aspirants’ beliefs about race and race issues, as well as awareness; integrating issues of race across all courses supported aspirants in being able to examine race on a daily basis; the program provided aspirants with key skills to advance anti-racism in their buildings |

| Gooden et al., 2023 [84] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Literature Review | Culturally responsive leadership | Explore the literature to understand the role of culturally responsive leadership within principal pipelines, including (but not limited to) preparation | N/A | N/A |

| Gordon, 2012 [98] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Theoretical/conceptual essay | Social justice leadership | Advances a framework for leadership preparation for equity and social justice | N/A | N/A |

| Gray and Reis, 2021 [33] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Literature Review: Review of the literature within the CAPEA journal and more broadly | Leadership for social justice | Examine the literature related to leadership preparation for diversity and social justice within California and create a framework for preparation for justice for the CAPEA journal | N/A | N/A |

| Grooms et al., 2024 [83] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Theoretical/conceptual essay | Equity-oriented leadership | Discuss the application of an equity lens to key content areas within principal preparation programs, specifically relationships, culturally diverse leadership practice, and practical applications | N/A | N/A |

| Guerra et al., 2013 [105] | Descriptive | Qualitative: Focus groups with twelve program graduates | Social justice leadership | Examine programmatic elements of preparation program using Brown’s (2004) framework | United States | Reading the literature around inequities and engaging in tough discussions in the classroom that challenged deficit thinking, as well as action research work, increased aspirants’ self-awareness and understandings of social justice, self-efficacy to conduct justice work, and desire toward justice work |

| Guillaume et al., 2020 [106] | Empirical | Qualitative: Interviews with ten program graduates | Social justice leadership | Explore how program graduates from one program operationalized social justice to inform their praxis following graduation. | Southwest | Strong partnerships with local community leaders and schools provided opportunities for participants to practice justice skills; program emphasis on justice provided knowledge and opportunities to learn around justice issues |

| Guillaume, 2021 [46] | Empirical | Qualitative: Interviews with ten program graduates | Social justice leadership | Examine graduates from one preparation program that sought to create more socially just educational outcomes | Southwest | Courses describing “Sensitive issues”, cultural responsiveness, and asset-based views; internships; infusing all courses with social justice issues; self-reflective assignments; discussion and being exposed to classmates’ stories—all impacted program graduates’ understandings and abilities to undertake justice practice |

| Harris and Hopson, 2008 [142] | Empirical | Qualitative: 75 student responses to open-ended survey with five questions | Social justice leadership | Describe the use of equity audits as part of a preparation program curriculum | Texas | Following the use of equity audits within the program, program aspirants saw actual changes made within their districts, such as district reviews of and changes to disciplinary policies; equity audits were a new tool for aspirants to use within their settings |

| Henry and Cobb, 2021 [34] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Literature Review | Social justice leadership | Examine reorientations of program curriculum, learning experiences, and structures toward socially just leadership preparation, with a focus on whole system reform and coherence | N/A | N/A |

| Hernandez and McKenzie, 2010 [23] | Descriptive | Qualitative: Interviews with individuals involved in the conceptualization and design of program as well as a student who had participated in it | Social justice leadership | Examine a leadership program that centers social justice to learn key elements of the program and resistance faced within the program | Upper Midwest | N/A |

| Hesbol, 2013 [66] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Theoretical/conceptual essay | Broad; leadership that can re-culture schools | A specific purpose within this piece is difficult to track but it centers on the preparation of leaders who can lead more inclusive and just schools | N/A | N/A |

| Honig and Donaldson Walsh, 2019 [38] | Descriptive | Qualitative narrative accounting of the program redesign process written by program faculty (no methods section) | Equity-oriented leadership | An example of how one leadership program works to implement equity within its design and the effects of that implementation | University of Washington | N/A |

| Jean-Marie et al., 2009 [27] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Theoretical/conceptual essay | Social justice leadership | Explore key themes in the literature around principal preparation for social justice | N/A | N/A |

| Jones and Ringler, 2017 [114] | Empirical | Quantitative: Aspirants completed a survey (Anti-Defamation League “Assessing Your Self” survey) at the beginning and end of the survey | Equity-oriented leadership | Examine whether embedding diversity topics within a principal preparation program would change aspirants’ self-awareness and general awareness of biases | North Carolina | Aspirants showed positive change in their general self-awareness of biases and biases they saw within school/community |

| Jones, 2023 [114] | Empirical | Mixed Method: Quantitative data from the use of the Multicultural Efficacy Scale; qualitative focus groups | Multicultural leadership | Examine whether/how aspirants’ multicultural efficacy is influenced by participation in diversity seminars that include reflective activities during the internship period | Does not specify | Aspirants’ attitudes and self-efficacy around multicultural leadership improved over the year; aspirants better understood topics around justice and biases, and felt that they had gained knowledge they could use to make a positive impact for students |

| Karanxha et al., 2014 [155] | Descriptive | Mixed Method: Quantitative data related to applicants, their respective demographics, and outcomes; Qualitative field notes and emails | Broad; diversity of leader pipeline | Describe one program’s recruitment and selection process and the ways in which this process affected diversity within aspirant cohorts | Florida | N/A |

| Kemp-Graham, 2015 [47] | Empirical | Quantitative: 106 program graduates completed the Diversity and Oppression, and Cultural Diversity, Self Confidence, and Awareness subscales | Social justice leadership | Explore the readiness of recent principal preparation program graduates in one Texas program to take up issues of justice in their work | Texas | Program completers did not have strong understandings of diversity/oppression issues |

| Lac and Diaz, 2023 [102] | Empirical | Mixed Method: Student work such as journals; Field notes; Pre- and post-survey with open-ended and Likert questions; Interviews | Community-based leadership | Examine experiences of three aspirant leaders within a justice-centered preparation program | Large urban center in Southwest | As a result of the coursework aspirants transformed in their ability to see educational leadership from a more community-based, collaborative lens; aspirants also found clarity in their understandings of previous educational experiences and the ways schools are structured now |

| Leggett and Smith, 2022 [134] | Empirical | Qualitative: Reviewed aspirants’ written responses to a specific case study that was included within the course | Equity-oriented leadership | Examine the use of case method within one leadership preparation program as a means to develop aspirants’ ability to address equity issues | Western Kentucky University | The use of case method allowed for aspirants to see perspectives they previously had not thought of, and to shift their thinking from classroom teachers to taking on an administrator role, as well as to connect classroom learning toward problem-solving for an actual problem of practice |

| Leggett et al., 2022 [40] | Descriptive | Qualitative narrative accounting of the program redesign process written by program faculty (no methods section) | Equity-oriented leadership | Describe one program’s experiences in redesign (including redesign around embedding equity) as part of the Wallace Foundation UPPI initiative, specifically looking at partnerships | Western Kentucky University | N/A |

| Leggett et al., 2023 [75] | Descriptive | Qualitative narrative accounting of the program redesign process written by program faculty (no methods section) | Equity-oriented leadership | Examine the process one university preparation program went through to infuse stronger coherence toward equity issues within the program | Western Kentucky University | N/A |

| Liou and Hermanns, 2017 [89] | Empirical | Qualitative narrative accounting of the program redesign process written by program faculty (no methods section) | Transformative leadership | Describe one preparation program’s redesign around issues of equity, and the actual preparation processes used to prepare leaders who can transform their schools toward equity | Arizona | The redesign around equity appears to be influencing aspirants’ understandings of issues of equity and leadership practice, such as one aspirant’s ability to see more clearly deficit mindsets of teachers via an action research project |

| López et al., 2006 [107] | Descriptive | Qualitative: Survey of educational leadership faculty across California who were engaged in leading for equity work (appears to be an open-ended survey but this is unclear; numerical data not provided) | Leadership for equity | Provides results from a survey across California professors of educational administration that describes key program facets for equity-centered preparation | California | N/A |

| Marshall and Hernandez, 2013 [91] | Empirical | Qualitative: Analyses of aspirants’ reflections within and across the two courses, which included online discussion board exchanges | Leadership for LGBTQ+ students | Examine one program’s efforts to develop aspirants around LGBTQ via two justice-related courses that deeply embedded LGBTQ+ issues, including whether coursework changed student understanding | Aspirants drawn from rural areas, program in a fairly small city | While there was evidence that aspirants’ beliefs about sexual orientation changed across the two courses, it was not necessarily deep or passionate change, and aspirants continued to largely ignore issues of sexual orientation |

| Marshall and Theoharis, 2007 [108] | Empirical | Qualitative narrative accounting of the program redesign process written by program faculty (no methods section) | Leadership for social justice | Describe one program’s justice-centered foundations course | Does not specify | Aspirants’ reflections and perspectives indicate that some of the course topics and pedagogical structures were impactful to their thinking, such as educational plunges |

| Mayger, 2024 [127] | Descriptive | Qualitative: Content analysis of syllabi across programs, with a sample of 50 syllabi brought in for in-depth analysis | Broad, leadership that incorporates family and community engagement | Examine principal preparation program syllabi across twelve states to determine how family and community engagement is incorporated within these programs | Twelve states across U.S. | N/A |

| McClellan and Dominguez, 2006 [121] | Descriptive | Qualitative narrative accounting of the program redesign process written by program faculty (no methods section) | Leadership for justice | Descriptions of two programs that have sought to orient around issues of justice and away from the status quo | New Mexico State University | N/A |

| McKenzie et al., 2008 [99] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Theoretical/conceptual essay | Social justice leadership | Advance a conceptual framing of key components for preparing aspiring school leaders to engage in social justice work, with a focus on aspirant selection and the academic program | N/A | N/A |

| Melloy, 2019 [125] | Descriptive | Qualitative: No specific data, but historic accounting of program | Inclusive | Conceptual examination of standards and evidence-based practices oriented around inclusive schools, as well as describe efforts of one program to redesign toward this end | California | N/A |

| Merchant and Garza, 2015 [113] | Empirical | Qualitative narrative accounting of the program redesign process written by program faculty (no methods section) | Leadership for social justice | Provides significant insight into program design for justice and into program outcomes across several areas within the Urban School Leaders Collaborative in San Antonio | University of Texas San Antonio | Aspirants’ self-assessments report that the program has helped to develop their awareness of justice issues and ability to “walk the walk” of justice leadership |

| Miller, 2021 [29] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Theoretical/conceptual essay | Anti-racist leadership | Discuss anti-racist training as a part of leadership preparation programs | N/A | N/A |

| Mullen, 2017 [80] | Empirical | Qualitative: Literature review followed by a review of student papers, presentations, and open-ended survey responses completed by 21 aspirants across two semesters | Ethical leadership | Examine the use of ethics coursework in preparing school leaders who can go on to engage in ethical leadership | Does not specify, but aspirants were located in rural areas, small towns, and a small city | There was evidence that aspirants engaged in ethics coursework shifted in their critical consciousness and dispositions around ethical leadership |

| O‘Malley and Capper, 2015 [22] | Descriptive | Quantitative: Survey completed by 218 faculty across 53 UCEA member institution preparation programs | Social justice leadership, specific eye to LGBTQ+ issues | Provides descriptive results from a survey of educational leadership professors that indicates the sorts of program instruction and other aspects programs use to address LGBTIQ matters | United States | N/A |

| Polizzi and Frick, 2012 [138] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Theoretical/conceptual essay | General, leaders who can create schools in which everyone thrives | Advance a theory of authentic pedagogical methods for developing school leaders, specifically reflection | N/A | N/A |

| Pounder et al., 2002 [112] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Theoretical/conceptual essay | Leadership for justice | Discuss content, instruction, and other program design elements within preparation programs that prepare aspirants for justice | N/A | N/A |

| Rasmussen and Raskin, 2023 [49] | Empirical | Qualitative: Focus groups with five Black male aspirants and four white male aspirants | Anti-racist leadership | Examine the ways in which a preparation program centered on race and anti-racism influenced aspirants’ development | Does not specify but aspirants worked in rural, suburban, and urban districts | Aspirants increased in their awareness and understanding of issues of race and racism and felt more prepared to lead schools in racially just ways; this occurred differentially for white and Black male aspirants |

| Reis and Smith, 2013 [120] | Descriptive | Qualitative narrative accounting of the program redesign process written by program faculty (no methods section) | Culturally proficient leadership | Examine how preparation programs can develop culturally proficient school leaders by reviewing the relevant literature and one program’s model | Does not specify | N/A |

| Reyes-Guerra et al., 2022 [44] | Empirical | Qualitative: Interviews and focus groups with district representatives and university/faculty representatives involved with the program; document analysis to triangulate | Broad; diversity of leader pipeline | Examine how one university–district partnership led to a diversified school leadership pipeline | Urban/suburban | Concerted and systematic recruitment efforts that included a nominations process and selection processes resulted in increases in diversity within the aspirants in the program; there was no formal affirmative action plan but there was an unspoken but commonly known focus on diversification |

| Richard and Cosner, 2022 [41] | Descriptive | Qualitative narrative accounting of the program redesign process written by program faculty (no methods section) | Equity-oriented leadership | Examine the actions that one program has taken to embed equity more deeply within its curriculum | University of Illinois Chicago | N/A |

| Rodriguez et al., 2010 [100] | Descriptive | Qualitative: No specific methods, qualitative descriptions of programs written by program faculty, cross-case compared by faculty members | Social justice leadership | Examine three social justice-oriented preparation programs to identify key program elements and resistance faced by these programs | Three across U.S. | N/A |

| Roegman et al., 2021 [135] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Literature Review: Empirical articles 2001-2018 based in U.S., 24 related to principal preparation | Leadership and race | Examine the teacher and principal preparation literature to understand how issues of race/racism are being addressed | N/A | N/A |

| Rusch, 2004 [156] | Descriptive | Quantitative: Survey of faculty members with forced choice and some open-ended questions | This was more related to experiences of preparation programs than leadership itself | Examine leadership program faculty perspectives on the inclusion of gender and race within their programs, as well as gender/race issues broadly within programs | United States, programs associated with UCEA | N/A |

| Salisbury and Irby, 2020 [39] | Descriptive | Qualitative narrative accounting of the program redesign process written by program faculty (no methods section) | Broad, equity and justice within instructional leadership | Describe one program’s process of redesigning a three-course instructional leadership strand to emphasize active learning and an equity orientation | University of Illinois Chicago | N/A |

| Samkian et al., 2022 [86] | Descriptive | Qualitative narrative accounting of the program redesign process written by program faculty (no methods section) | Anti-racist, culturally responsive, LGBTQ+ inclusive | Examine the redesign efforts of one program that is seeking to develop anti-racist, culturally responsive, and LGBTQ+ inclusive leaders, focusing on curricular development and the development of a dissertation in practice | USC Rossier | N/A |

| Secatero et al., 2022 [157] | Empirical | Qualitative: Use a questionnaire (with open-ended responses) to elicit information from 34 aspirants who had gone through the program | Native-serving leadership | Examine the impact of one program on preparing aspirants who can lead Native-serving schools | University of New Mexico | Aspirants believed that the approach within the program transformed their understandings of Indigenous people/culture, and how they would plan to serve Indigenous people through school leadership |

| Stone-Johnson and Wright, 2020 [17] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Literature Review: Less explicit methods but they looked to the literature broadly and specifically sought out articles in the five journals included in Diem and Carpenter’s (2012) piece | Leadership for social justice | Examine the state of leadership preparation for social justice, with a specific eye to the updated PSEL standards and how these have influenced preparation | N/A | N/A |

| Theoharis and Causton-Theoharis, 2008 [118] | Descriptive | Qualitative: Interviews, document analysis, and a field log, captured from three national experts of school leadership preparation, development, and intersection of these with issues of diversity and inclusion | Inclusive leadership | Outline key dispositions aspirants need to develop to engage in inclusive leadership for all students | Not a specific program | N/A |

| Thornton et al., 2022 [97] | Descriptive | Qualitative: Documents from various NIC meetings, site visit, and NIC participant knowledge (i.e., faculty knowledge) gained through interviews | Broad; diversity of leader pipeline | Examine the work of two preparation programs that sought to create more diverse applicant pools more centered around issues of diversity/justice via participation in a NIC | Florida Atlantic University and University of Iowa | N/A |

| Trujillo and Cooper, 2014 [81] | Descriptive | Qualitative: Review 26 syllabi to examine whether social justice framework was guiding courses | Social justice leadership | Examine the ways in which one program’s curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment reflect a social justice leadership preparation framework | University of California Berkeley and Los Angeles | N/A |

| Voulgarides et al., 2022 [92] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Theoretical/conceptual essay | Inclusive leadership for students with disabilities | Propose a framework for the preparation of school leaders who can attend to issues of disability and inclusion | N/A | N/A |

| Waite, 2021 [109] | Empirical | Qualitative: Course assignments and course syllabi, collected from 133 aspirants over two years | Culturally responsive, anti-racist leadership | Examine the use of specific pedagogical practices in developing culturally responsive, anti-racist school leaders | Fordham University | Aspirants indicated that the course pedagogies pushed them toward critical reflection, self-examination, and to consider how to put their new knowledge into practice |

| Weiler and Lomotey, 2022 [95] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Theoretical/conceptual essay | Leadership for justice | Advance a conceptual framework that identifies what rigor looks like within EdD programs centered around issues of equity and justice | N/A | N/A |

| Whitenack et al., 2019 [158] | Literature or Theoretical/Conceptual | Theoretical/conceptual essay | Leadership for equity, broadly, with focus on intersectionality | Advance a framework for the preparation of school leaders who can engage with issues of intersectionality to address inequities | N/A | N/A |

| Woods and Hauser, 2013 [101] | Descriptive | Mixed Method: Online survey with Likert-type and open-ended responses, interviews, and document review, all with program faculty/instructors in California preparation programs | Social justice leadership | Describes the curriculum of a social justice-focused preparation program and processes used to better align this curriculum around justice | California | N/A |

| Wright et al., 2020 [137] | Empirical | Mixed Method: Analysis of rubric scores that assess aspirants’ reflective writing; also incorporated meeting notes | Equity-oriented leadership | Examine the use of reflective writing within one program’s efforts to prepare equity-driven school leaders | San Diego State University | Aspirants increased in their awareness of issues of equity through the use of their reflections |

| Yamashiro et al., 2022 [159] | Descriptive | Qualitative narrative accounting of the program redesign process written by program faculty (no methods section) | Broad; diversity of leader pipeline | Examine one preparation program’s efforts to diversify its pipeline | Metropolitan city in Southern California | N/A |

| Young et al., 2006 [115] | Empirical | Qualitative: Interviews with 27 aspirants who had engaged in the coursework | Gender and diversity issues within leadership | Examine the impact of using readings that explore gender, diversity, leadership, and feminism within a preparation program | Does not specify | While aspirants had engaged in readings and other coursework exploring gender and diversity issues, few had transformed in their understandings of these issues, and many resisted the readings |

| Young et al., 2021 [61] | Descriptive | Book draws from the literature and qualitative narratives of program experiences | Equity, broad | Book that provides insights into redesign processes for equity across several program elements | N/A | N/A |

| Zarate and Mendoza, 2020 [48] | Empirical | Qualitative: Analysis of peer reflection letters exchanged between aspirants across two semesters | Social justice leadership | Examine the use of a peer letter exchange within one program that aimed to develop aspirants’ understanding of race and privilege | Southern California | For some aspirants the peer reflection letters prompted authentic reflection about race and privilege and development of consciousness, but other aspirants resisted such transformation and dismissed issues of race/privilege |

References

- Pont, B. School Leadership for Equity: A Comparative Perspective. In The Impact of the OECD on Education Worldwide; Wiseman, A., Taylor, C.S., Eds.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2017; pp. 99–124. [Google Scholar]

- Grissom, J.A.; Egalite, A.J.; Lindsay, C.A. How Principals Affect Students and Schools: A Systematic Synthesis of Two Decades of Research; The Wallace Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz, D.D.; Porter, L. The Effect of Principal Behaviors on Student, Teacher, and School Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Empirical Literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 2019, 89, 003465431986613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Hallinger, P.; Ko, J. Principal Leadership and School Capacity Effects on Teacher Learning in Hong Kong. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2016, 30, 76–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerens, J.; Bosker, R. The Foundations of Educational Effectiveness; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mendels, P. Improving University Principal Preparation Programs: Five Themes from the Field; The Wallace Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grissom, J.A.; Mitani, H.; Woo, D.S. Principal Preparation Programs and Principal Outcomes. Educ. Adm. Q. 2019, 55, 73–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Wechsler, M.E.; Levin, S.; Leung-Gagne, M.; Tozer, S. Developing Effective Principals: What Kind of Learning Matters? Learning Policy Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gümüş, S.; Hallinger, P.; Cansoy, R.; Bellibaş, M.Ş. Instructional Leadership in a Centralized and Competitive Educational System: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis of Research from Turkey. J. Educ. Adm. 2021, 59, 702–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, B. Principal Preparation and Development: Highly Regulated or Loosely Structured? Available online: https://globaledleadership.org/2018/04/11/principal-preparation-and-development-highly-regulated-or-loosely-structured/ (accessed on 29 July 2024).

- Slater, C.; Garcia Garduno, J.M.; Mentz, K. Frameworks for Principal Preparation and Leadership Development: Contributions of the International Study of Principal Preparation (ISPP). Manag. Educ. 2018, 32, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, M.T.; Orphanos, S. How Graduate-Level Preparation Influences the Effectiveness of School Leaders: A Comparison of the Outcomes of Exemplary and Conventional Leadership Preparation Programs for Principals. Educ. Adm. Q. 2011, 47, 18–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booker, K.; Thomas, J. Impacts of New Leaders on Student Achievement in Oakland; Mathematica Policy Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gates, S.M.; Hamilton, L.S.; Martorell, P.; Burkhauser, S.; Paul, H.; Ashley, P.; Baird, M.D.; Vuollo, M.; Li, J.J.; Lavery, D.C.; et al. Preparing Principals to Raise Student Achievement: Implementation and Effects of the New Leaders Program in Ten Districts; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, M.J.; Kapur, M.; Reimann, P. Conceptualizing Debates in Learning and Educational Research: Toward a Complex Systems Conceptual Framework of Learning. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 51, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosner, S. What Makes a Leadership Preparation Program Exemplary? J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2019, 14, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone-Johnson, C.; Wright, C. Leadership Preparation for Social Justice in Educational Administration. In Handbook on Promoting Social Justice in Education; Papa, R., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1065–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Barakat, M.; Reyes-Guerra, D.; Stefanovic, M.; Shatara, L. An Examination of the Relationship between a Redesigned School Leadership Preparation Program and Graduates’ Cultural Competence. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2021, 20, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne-Ferrigno, T. Redesigning Preparation Programs for Teacher Leaders and Principals. In Redesigning Professional Education Doctorates; Storey, V.A., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 121–141. [Google Scholar]

- Garver, R.; Maloney, T. Redefining Supervision: A Joint Inquiry into Preparing School-Based Leaders to Supervise for Equity. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2020, 15, 330–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.L. Enriching Educational Leadership through Community Equity Literacy: A Conceptual Foundation. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2018, 17, 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, M.; Capper, C. A Measure of the Quality of Educational Leadership Programs for Social Justice: Integrating LGBTIQ Identities into Principal Preparation. Educ. Adm. Q. 2015, 51, 290–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, F.; McKenzie, K.B. Resisting Social Justice in Leadership Preparation Programs: Mechanisms That Subvert. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2010, 5, 48–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.M. Leadership for Social Justice and Equity: Weaving a Transformative Framework and Pedagogy. Educ. Adm. Q. 2004, 40, 77–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, G. Social Justice Leadership as Praxis. Educ. Adm. Q. 2012, 48, 191–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooden, M.A.; Dantley, M. Centering Race in a Framework for Leadership Preparation. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2012, 7, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean-Marie, G.; Normore, A.H.; Brooks, J.S. Leadership for Social Justice: Preparing 21st Century School Leaders for a New Social Order. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2009, 4, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkovich, I. Reflections on Leadership Preparation Programs and Social Justice: Are the Power and the Responsibility of the Faculty All in the Design? J. Educ. Adm. 2017, 55, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P. Anti-Racist School Leadership: Making ‘Race’ Count in Leadership Preparation and Development. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2021, 47, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capper, C.; Theoharis, G.; Sebastian, J. Toward a Framework for Preparing Leaders for Social Justice. J. Educ. Adm. 2006, 44, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne-Jiménez, M.; Orr, M.T. Evaluating Social Justice Leadership Preparation. In Handbook of Research on Educational Leadership for Equity and Diversity; Tillman, L.C., Scheurich, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 670–702. [Google Scholar]

- Diem, S.; Carpenter, B. Social Justice and Leadership Preparation: Developing a Transformative Curriculum. Plan. Chang. 2012, 43, 96–112. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M.S.; Reis, N.M. From Preparation to the Principalship: Towards a Framework for Social Justice in Leadership. Educ. Leadersh. Adm. Teach. Program Dev. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, W.; Cobb, C. Social Justice Leadership Design: Reorienting University Preparation Programs. In Handbook of Social Justice Interventions in Education; Mullen, C.A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 931–953. [Google Scholar]

- Arzu, E.; Agan, T.; Miller, G.; Badgett, K. The Role of Stakeholders: Implications for Continuous Improvement in Principal Preparation. Sch. Leadersh. Rev. 2023, 17, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne-Jiménez, M.; Borden, A.M. Diversifying Doctoral-Level Leadership Preparation: Need versus Reality. Int. J. Educ. Reform 2015, 24, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.E. Horton, Highlander, and Leadership Education: Lessons for Preparing Educational Leaders for Social Justice. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2007, 17, 250–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honig, M.I.; Donaldson Walsh, E. Learning to Lead the Learning of Leaders: The Evolution of the University of Washington’s Education Doctorate. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2019, 14, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, J.; Irby, D.J. Leveraging Active Learning Pedagogy in a Scaffolded Approach: Reconceptualizing Instructional Leadership Learning. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2020, 15, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggett, S.; Desander, M.; Evans, S. Partnering in Principal Preparation Program Redesign. Educ. Renaiss. 2022, 11, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, M.; Cosner, S. Using Cycles of Inquiry to Drive Equity-Oriented Curricular Improvement within One Leadership Preparation Program. In Equity & Access: An Analysis of Educational Leadership Preparation, Policy & Practice; Fowler, D., Vasquez Heilig, J., Jouganatos, S., Johnson, A., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2022; pp. 17–39. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.M. Leadership for Social Justice and Equity: Evaluating a Transformative Framework and Andragogy. Educ. Adm. Q. 2006, 42, 700–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, B.W.; Diem, S. Talking Race: Facilitating Critical Conversations in Educational Leadership Preparation Programs. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2013, 23, 902–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Guerra, D.; Barakat, M.; Maslin-Ostrowski, P. Developing a More Diversified School Leadership Pipeline: Recruitment, Selection and Admission through an Innovative University-District Partnership. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2022, 21, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooden, M.A.; O’Doherty, A. Do You See What I See? Fostering Aspiring Leaders’ Racial Awareness. Urban Educ. 2015, 50, 225–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaume, R.O. Formal Knowledge Acquisition and Socialization to Educational Leadership by Program Graduates: The Intersection of Social Justice and the Role of Program Faculty. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2021, 16, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp-Graham, K.Y. Missed Opportunities: Preparing Aspiring School Leaders for Bold Social Justice School Leadership Needed for 21st Century Schools. Int. J. Educ. Leadersh. Prep. 2015, 10, 99–129. [Google Scholar]

- Zarate, M.E.; Mendoza, Y. Reflections on Race and Privilege in an Educational Leadership Course. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2020, 15, 56–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, N.; Raskin, C. Men’s Voices: Black and White Aspiring Principals Reflect on Their Preparation to Be Racial Equity Leaders. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2023, 18, 228–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The Integrative Review: Updated Methodology. Methodol. Issues Nurs. Res. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, C. School Principals’ Preparation in Spain and in the USA: Alignments between Higher Education and Supranational Recommendations. Rev. Española De Educ. Comp. 2020, 37, 299–321. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, M. Partners for Possibility: How Business Leaders and Principals Are Igniting Radical Change in South African Schools; Knowres Publishing: Randburg, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Oplatka, I.; Waite, D. The New Principal Preparation Program Model in Israel: Ponderings about Practice-Oriented Principal Training. Adv. Educ. Adm. 2010, 11, 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, E.; Gates, S.; Herman, R.; Mean, M.; Perera, R.; Tsai, T.; Whipkey, K.; Andrew, M. Launching a Redesign of University Principal Preparation Programs: Partners Collaborate for Change; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J. Preparation for the School Principalship: The United States’ Story. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 1998, 18, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, T.; Jackson, D. A Preparation for School Leadership: International Perspectives. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2002, 30, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozer, S.; Zavitovsky, P.; Martinez, P. Change Agency in Our Own Backyards: Meeting the Challenges of next Generation Programs in School Leader Preparation. In Handbook for Urban Educational Leadership; Khalifa, M., Arnold, N., Osanloo, A.F., Grant, C.M., Eds.; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2015; pp. 480–495. [Google Scholar]

- Crow, G.M.; Whiteman, R.S. Effective Preparation Program Features: A Literature Review. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2016, 11, 120–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.; Bryant, D.; Lee, M. International Patterns in Principal Preparation: Commonalities and Variations in Pre-Service Programmes. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2013, 41, 405–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. A Conceptual Framework for Systematic Reviews of Research in Educational Leadership and Management. J. Educ. Adm. 2013, 51, 126–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.; O’Doherty, A.; Cunningham, K. Redesigning Educational Leadership Preparation for Equity: Strategies for Innovation and Improvement; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, S.H.; Darling-Hammond, L. Innovative Principal Preparation Programs: What Works and How We Know. Plan. Chang. 2012, 43, 25–45. [Google Scholar]

- Young, M. Effective Leadership Preparation: We Know What It Looks like and What It Can Do. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2015, 10, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosner, S.; Tozer, S.; Zavitkovsky, P.; Whalen, S. Cultivating Exemplary School Leadership Preparation at a Research Intensive University. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2015, 10, 11–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; LaPointe, M.; Meyerson, D.; Orr, M. Preparing School Leaders for a Changing World: Lessons from Exemplary Leadership Development Programs; The Wallace Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hesbol, K.A. Preparing Leaders to Reculture Schools as Inclusive Communities of Practice. In Handbook of Research on Educational Leadership for Equity and Diversity; Tillman, L.C., Scheurich, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 603–624. [Google Scholar]

- Orphanos, S.; Orr, M.T. Learning Leadership Matters: The Influence of Innovative School Leadership Preparation on Teachers’ Experiences and Outcomes. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2014, 42, 680–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, C. Quality Measures Principal Preparation Program Self-Study Toolkit: For Use in Developing, Assessing, and Improving Principal Preparation Programs, 10th ed.; Education Development Center: Waltham, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Donmoyer, R.; Yennie-Donmoyer, J.; Galloway, F. The Search for Connections across Principal Preparation, Principal Performance, and Student Achievement in an Exemplary Principal Preparation Program. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2012, 7, 5–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballenger, J.; Alford, B.; Mccune, S.; Mccune, D. Obtaining Validation from Graduates on a Restructured Principal Preparation Program. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2009, 19, 533–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Education. Innovative Pathways to School Leadership; U.S. Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- DeMatthews, D.E.; Kotok, S.; Serafini, A. Leadership Preparation for Special Education and Inclusive Schools: Beliefs and Recommendations from Successful Principals. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2020, 15, 303–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.; Mawhinney, H.; Reed, C. Leveraging Standards to Promote Program Quality. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2016, 11, 12–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, D.; Thornton, M.; Miles Nash, A.; Sanzo, K. Attributes of Highly Diverse Principal Preparation Programs: Pre-Enrollment to Post-Completion. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2022, 21, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggett, S.R.; Desander, M.K.; Stewart, T.A. Lessons Learned from Designing a Principal Preparation Program: Equity, Coherence, and Collaboration. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2023, 18, 404–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcher, L.; Espinoza, A.; Espinoza, D. Supporting Principals’ Learning: Key Features of Effective Programs; Learning Policy Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, R.; Wang, E.L.; Woo, A.; Gates, S.M.; Berglund, T.; Schweig, J.; Andrew, M.; Todd, I. Redesigning University Principal Preparation Programs: A Systemic Approach for Change and Sustainability—Report in Brief (Volume 3, Part 2); RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne-Jiménez, M.; Gooden, M.A.; Tucker, P.D. Facilitating Learning in Leadership Preparation: Limited Research but Promising Practices. In Handbook of Research on the Education of School Leaders; Young, M., Crow, G., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 185–215. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, M.S. Andragogy, Not Pedagogy. Adult Learn. 1968, 16, 350–352. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen, C.A. What’s Ethics Got to Do with It? Pedagogical Support for Ethical Student Learning in a Principal Preparation Program. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2017, 12, 239–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, T.; Cooper, R. Framing Social Justice Leadership in a University-Based Preparation Program: The University of California’s Principal Leadership Institute. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2014, 9, 142–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L.S. Signature Pedagogies in the Professions. Daedalus 2005, 134, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grooms, A.A.; White, T.; Peters, A.L.; Childs, J.; Farrell, C.; Martinez, E.; Resnick, A.; Arce-Trigatti, P.; Duran, S. Equity as a Crucial Component of Leadership Preparation and Practice. Clear. House A J. Educ. Strateg. Issues Ideas 2024, 97, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooden, M.A.; Khalifa, M.; Arnold, N.; Brown, K.; Meyers, C.; Welsh, R. A Culturally Responsive School Leadership Approach to Developing Equity-Centered Principals: Considerations for Principal Pipelines; The Wallace Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Diem, S.; Carpenter, B.W.; Lewis-Durham, T. Preparing Antiracist School Leaders in a School Choice Context. Urban Educ. 2019, 54, 706–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samkian, A.; Pascarella, J.; Slayton, J. Towards an Anti-Racist, Culturally Responsive, and LGBTQ+ Inclusive Education: Developing Critically-Conscious Educational Leaders. In Cases on Academic Program Redesign for Greater Racial and Social Justice; Cain-Sanschagrin, E., Filback, R.A., Crawford, J., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 150–175. [Google Scholar]

- Baecher, L.; Knoll, M.; Patti, J. Targeted Observation of ELL Instruction as a Tool in the Preparation of School Leaders. Int. Multiling. Res. J. 2016, 10, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, R.; DeMatthews, D.; Reyes, P. The Impact of Brown on EL Students: Addressing Linguistic and Educational Rights through School Leadership Practice and Preparation. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2019, 14, 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liou, D.D.; Hermanns, C. Preparing Transformative Leaders for Diversity, Immigration, and Equitable Expectations for School-Wide Excellence. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2017, 31, 661–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capper, C.A.; Alston, J.; Gause, C.P.; Koschoreck, J.W.; Lopez, G.; Lugg, C.A.; McKenzie, K.B. Integrating Lesbian/Gay/Bisexual/Transgender Topics and Their Intersections with Other Areas of Difference into the Leadership Preparation Curriculum: Practical Ideas and Strategies. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2006, 16, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.M.; Hernandez, F. I Would Not Consider Myself a Homophobe: Learning and Teaching about Sexual Orientation in a Principal Preparation Program. Educ. Adm. Q. 2013, 49, 451–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulgarides, C.; Etscheidt, S.; Hernández-Saca, D. Racial and Dis/Ability Equity-Oriented Educational Leadership Preparation. J. Spec. Educ. Prep. 2022, 2, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, J.M. Advancing a Vision to Diversify the Workforce and Prepare Racially Conscious Educators. Educ. Plan. 2020, 27, 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gooden, M.A.; Davis, B.W.; Spikes, D.D.; Hall, D.L.; Lee, L. Leaders Changing How They Act by Changing How They Think: Applying Principles of an Anti-Racist Principal Preparation Program. Teach. Coll. Rec. Voice Scholarsh. Educ. 2018, 120, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, J.R.; Lomotey, K. Defining Rigor in Justice-Oriented EdD Programs: Preparing Leaders to Disrupt and Transform Schools. Educ. Adm. Q. 2022, 58, 110–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.D. Is State-Mandated Redesign an Effective and Sustainable Solution? J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2013, 8, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, M.E.; Barakat, M.; Grooms, A.A.; Locke, L.A.; Reyes-Guerra, D. Revolutionary Perspectives for Leadership Preparation: A Case of a Networked Improvement Community. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2022, 17, 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S.P. Beyond Convention, beyond Critique: Toward a Third Way of Preparing Educational Leaders to Promote Equity and Social Justice (Part 1). Int. J. Educ. Leadersh. Prep. 2012, 7, n2. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, K.; Christman, D.; Hernandez, F.; Fierro, E.; Capper, C.; Dantley, M.; Gonzalez, M.; Cambron-McCabe, N.; Scheurich, J. From the Field: A Proposal for Educating Leaders for Social Justice. Educ. Adm. Q. 2008, 44, 111–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M.A.; Chambers, T.V.; Gonzalez, M.L.; Scheurich, J.J. A Cross-Case Analysis of Three Social Justice-Oriented Education Programs. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2010, 5, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, R.S.; Hauser, L. University Preparation of K-12 Social Justice Leaders: Examination of Intended, Implemented, and Assessed Curriculum. Educ. Leadersh. Adm. Teach. Program Dev. 2013, 24, 16–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lac, V.T.; Diaz, C. Community-Based Educational Leadership in Principal Preparation: A Comparative Case Study of Aspiring Latina Leaders. Educ. Urban Soc. 2023, 55, 643–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, M.; Reames, E.; Kensler, L.A.W. Leadership Preparation Programs: Preparing Culturally Competent Educational Leaders. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2019, 14, 212–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celoria, D. The Preparation of Inclusive Social Justice Education Leaders. Educ. Leadersh. Adm. Teach. Program Dev. 2016, 27, 199–219. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra, P.; Nelson, S.; Jacobs, J.; Yamamura, E. Developing Educational Leaders for Social Justice: Programmatic Elements That Work or Need Improvement. Educ. Res. Perspect. 2013, 40, 124–149. [Google Scholar]

- Guillaume, R.O.; Saiz, M.S.; Amador, A.G. Prepared to Lead: Educational Leadership Graduates as Catalysts for Social Justice Raxis. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2020, 15, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J.A.; Magdaleno, K.R.; Reis, N.M. Developing Leadership for Equity: What Is the Role of Leadership Preparation Programs? Educ. Leadersh. Adm. Teach. Program Dev. 2006, 18, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, J.M.; Theoharis, G. Moving beyond Being Nice: Teaching and Learning about Social Justice in a Predominantly White Educational Leadership Program. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2007, 2, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, S.R. Disrupting Dysconsciousness: Confronting Anti-Blackness in Educational Leadership Preparation Programs. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2021, 31, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, M.; Rodela, K.C. A Framework for Rethinking Educational Leadership in the Margins: Implications for Social Justice Leadership Preparation. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2018, 13, 10–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everson, S.T.; Bussey, L. Educational Leadership for Social Justice: Enhancing the Ethical Dimension of Educational Leadership. J. Cathol. Educ. 2007, 11, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pounder, D.; Reitzug, U.; Young, M.D. Preparing School Leaders for School Improvement, Social Justice, and Community. Yearb. Natl. Soc. Study Educ. 2002, 101, 261–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, B.; Garza, E. The Urban School Leaders Collaborative: Twelve Years of Promoting Leadership for Social Justice. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2015, 10, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.D.; Ringler, M.C. Increasing Principal Preparation Candidates’ Awareness of Biases in Educational Environments. Int. J. Educ. Leadersh. Prep. 2017, 12, n1. [Google Scholar]

- Young, M.; Mountford, M.; Skrla, L. Infusing Gender and Diversity Issues into Educational Leadership Programs: Transformational Learning and Resistance. J. Educ. Adm. 2006, 44, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo-Brown, R.; Ringler, M.C.; James, M. Strengthening a Principal Preparation Internship by Focusing on Diversity Issues. Int. J. Educ. Leadersh. Prep. 2015, 10, 36–52. [Google Scholar]

- George, P. Toward a Social Justice Model for an EdD Program in Higher Education. Impacting Educ. J. Transform. Prof. Pract. 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharis, G.; Causton-Theoharis, J.N. Oppressors or Emancipators: Critical Dispositions for Preparing Inclusive School Leaders. Equity Excell. Educ. 2008, 41, 230–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boske, C. Aspiring School Leaders Addressing Social Justice through Art Making. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2012, 22, 116–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, N.M.; Smith, A. Rethinking the Universal Approach to the Preparation of School Leaders: Cultural Proficiency and Beyond. In Handbook of Research on Educational Leadership for Equity and Diversity; Tillman, L.C., Scheurich, J.J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 651–669. [Google Scholar]

- McClellan, R.; Dominguez, R. The Uneven March toward Social Justice: Diversity, Conflict, and Complexity in Educational Administration Programs. J. Educ. Adm. 2006, 44, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosto, V.; Dias, L.R.; Kaiza, N.; McHatton, P.A.; Elam, D. Culture-Based Leadership and Preparation: A Qualitative Metasynthesis of the Literature. In Handbook of Research on Educational Leadership for Equity and Diversity; Tillman, L.C., Scheurich, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 643–668. [Google Scholar]

- Genao, S. Doing It for Culturally Responsive School Leadership: Utilizing Reflexivity from Preparation to Practice. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2021, 16, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccotter, S.M.; Bulkley, K.E.; Bankowski, C. Another Way to Go: Multiple Pathways to Developing Inclusive, Instructional Leaders. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2016, 26, 633–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melloy, K.J. Preparing Educational Leaders for 21st Century Inclusive School Communities: Transforming University Preparation Programs. J. Transform. Leadersh. Policy Stud. 2019, 7, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ryan, J. Inclusive Leadership: A Review. J. Educ. Adm. Found. 2007, 18, 92–125. [Google Scholar]

- Mayger, L.K. How Are Principal Preparation Programs Preparing Leaders for Family and Community Engagement? J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2024, 19, 196–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, A. Re-Imagining Turnaround: Families and Communities Leading Educational Justice. J. Educ. Adm. 2018, 56, 546–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lash, C.L.; Burton, A.S.; Usinger, J. Developing Learning Leaders: How Modeling PLC Culture in Principal Preparation Can Shift the Leadership Views of Aspiring Administrators. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2024, 19, 167–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.; Bishop, Q. Leadership Development. J. Staff Dev. 2009, 30, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Stone-Johnson, C.; Hayes, S. Using Improvement Science to (Re)Design Leadership Preparation: Exploring Curriculum Change across Five University Programs. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2021, 16, 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggett, S.R.; Smith, K.C. Using Case Method to Address Equity-Related Gaps in Principal Aspirants’ Learning Experiences. Educ. Plan. 2022, 29, 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Roegman, R.; Kolman, J.; Goodwin, A.L.; Soles, B. Complexity and Transformative Learning: A Review of the Principal and Teacher Preparation Literature on Race. Teach. Coll. Rec. Voice Scholarsh. Educ. 2021, 123, 202–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, K.B.; Scheurich, J.J. Equity Traps: A Useful Construct for Preparing Principals to Lead Schools That Are Successful with Racially Diverse Students. Educ. Adm. Q. 2004, 40, 601–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.; Fisher, D.; Frey, N. Reflective Writing in a Principal Preparation Program. J. Sch. Adm. Res. Dev. 2020, 5, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polizzi, J.; Frick, W. Transformative Preparation and Professional Development: Authentic Reflective Practice for School Leadership. Teach. Learn. J. Nat. Inq. Reflective Pract. 2012, 26, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, G.E. Courageous Conversations About Race: A Field Guide for Achieving Equity in Schools; Corwin Press: Dallas, TX, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4833-8846-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hawley, W.; James, R. Diversity-Responsive School Leadership. UCEA Rev. 2010, 51, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Alford, B.; Hendricks, S. Partnering with Districts in Principal Preparation: Key Program Features in Strengthening Aspiring Rincipals’ Understanding of Issues of Equity and Excellence. Sch. Leadersh. Rev. 2018, 8, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, S.; Hopson, M. Using an Equity Audit Investigation to Prepare Doctoral Students for Social Justice Leadership. Teach. Dev. 2008, 12, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, D.S.; DeMatthews, D.E. Expanding the Use of Educational Data for Social Justice: Lessons from the Texas Cap on Special Education and Implications for Practitioner–Scholar Preparation. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2020, 15, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T. Community-Based Equity Audits. Educ. Adm. Q. 2017, 53, 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, R.M.; Nelson, J.A.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Assessing Schoolwide Cultural Competence: Implications for School Leadership Preparation. Educ. Adm. Q. 2009, 45, 793–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrla, L.; Scheurich, J.J.; Garcia, J.; Nolly, G. Equity Audits: A Practical Leadership Tool for Developing Equitable and Excellent Schools. Educ. Adm. Q. 2004, 40, 133–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brechenmacher, S. Comparing Democratic Distress in the United States and Europe; Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Terrón Cusí, A.; Selee, A. As Europe and the United States Face Similar Migration Challenges, Spain Can Act as a Bridge; Migration Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- DEI Legislation Tracker. Available online: https://www.chronicle.com/article/here-are-the-states-where-lawmakers-are-seeking-to-ban-colleges-dei-efforts (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Orr, M.T. Reflections on Leadership Preparation Research and Current Directions. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billingsley, B.; DeMatthews, D.; Connally, K.; McLeskey, J. Leadership for Effective Inclusive Schools: Considerations for Preparation and Reform. Australas. J. Spec. Incl. Educ. 2018, 42, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boske, C. Sending Forth Tiny Ripples of Hope That Build the Mightiest of Currents: Understanding How to Prepare School Leaders to Interrupt Oppressive Practices. Plan. Chang. 2012, 43, 183–197. [Google Scholar]

- Clement, D.; Young, M.D. Building a More Diverse School Leadership Workforce: What’s the Hold-Up? Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2022, 21, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, E.J.; Young, M.D. Challenges and Opportunities in Diversifying the Leadership Pipeline: Flow, Leaks and Interventions. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2022, 21, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanxha, Z.; Agosto, V.; Bellara, A.P. The Hidden Curriculum: Candidate Diversity in Educational Leadership Preparation. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2014, 9, 34–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusch, E.A. Gender and Race in Leadership Preparation: A Constrained Discourse. Educ. Adm. Q. 2016, 40, 16–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secatero, S.; Williams, S.; Romans, R. A Pathway to Leadership for Diverse Cadres of School Leaders: Honoring Indigenous Values in a Principal Preparation Program in New Mexico. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2022, 21, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitenack, D.A.; Golloher, A.N.; Burciaga, R. Intersectional Reculturing for All Students: Preparation and Practices for Educational Leaders. Educ. Leadersh. Adm. Teach. Program Dev. 2019, 31, 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashiro, K.; Huchting, K.; Ponce, M.N.; Coleman, D.A.; McGowan-Robinson, L. Increasing School Leader Diversity in a Social Justice Context: Revisiting Strategies for Leadership Preparation Programs. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2022, 21, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Richard, M.S.; Cosner, S. Centering Equity within Principal Preparation and Development: An Integrative Review of the Literature. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 944. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090944

Richard MS, Cosner S. Centering Equity within Principal Preparation and Development: An Integrative Review of the Literature. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(9):944. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090944