Diagnostic and Feedback Behavior of German Pre-Service Teachers Regarding Argumentative Pupils’ Texts in Geography Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What experiences and attitudes do pre-service geography teachers have towards diagnosing pupils’ argumentative competencies in geography education?

- How do pre-service geography teachers practice diagnosing pupils’ argumentative competence based on their argumentative texts?

- How do pre-service geography teachers give feedback on pupils’ argumentative texts?

2. Theory

2.1. Written Argumentation (Skills) in Geography Education

2.2. Diagnostic (Skills)

2.3. Diagnostic of Pupils’ Written Argumentative Skills in Geography Lessons

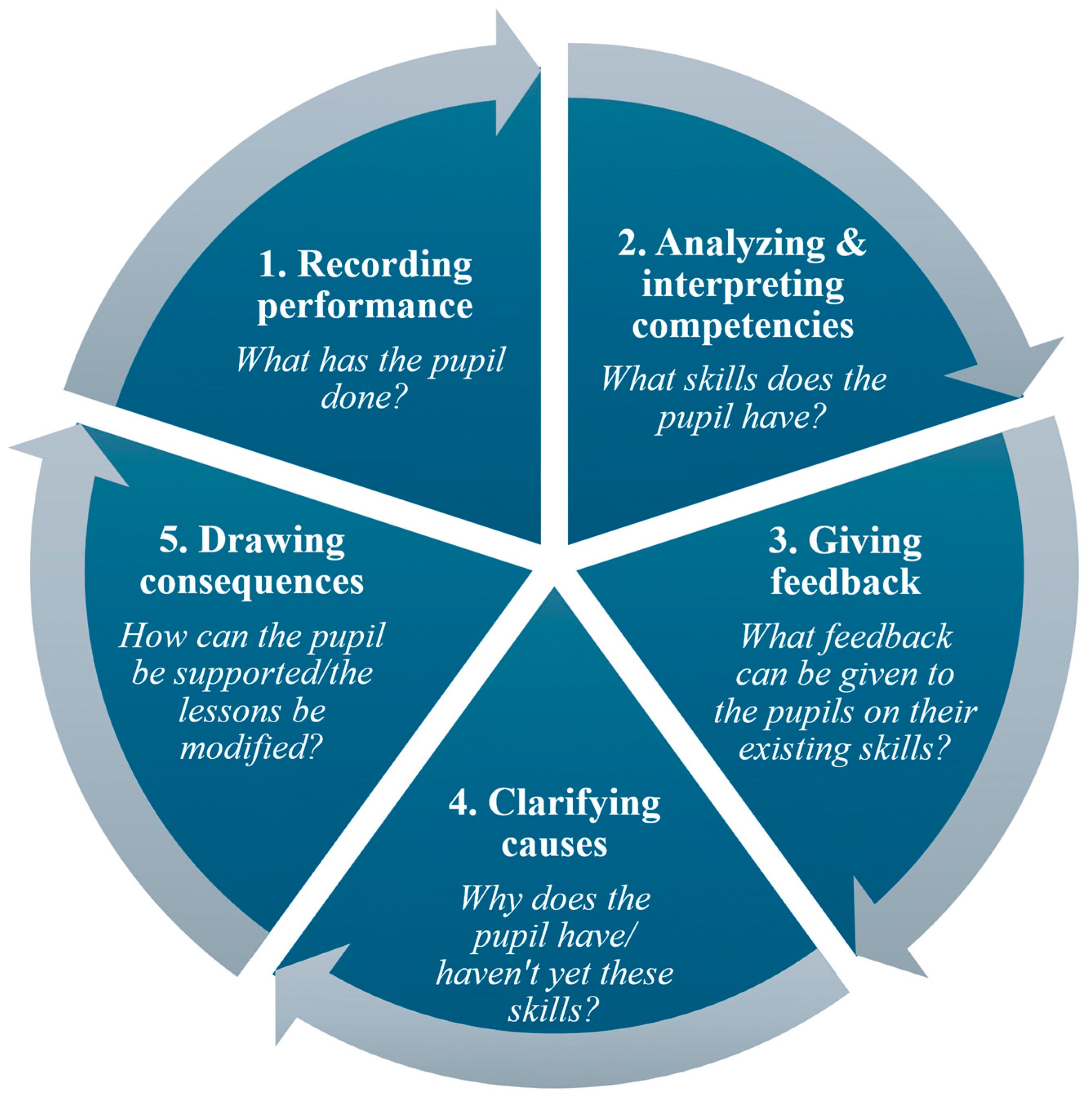

- 1.

- Recording performance

- What does this mean in relation to argumentative pupil texts?

- 2.

- Analyzing and interpreting competencies

- What does this mean in relation to argumentative pupil texts?

- 3.

- Giving feedback

- What does this mean in relation to argumentative pupil texts?

- 4.

- Clarifying causes

- What does this mean in relation to argumentative pupil texts?

- 5.

- Drawing consequences

- What does this mean in relation to argumentative pupil texts?

3. Current State of Research on Diagnostics and Feedback

4. Methods

4.1. Research Design

4.2. Research Questions and Methods

4.3. Sample

5. Results

5.1. Experiences and Attitudes of Pre-Service Geography Teachers

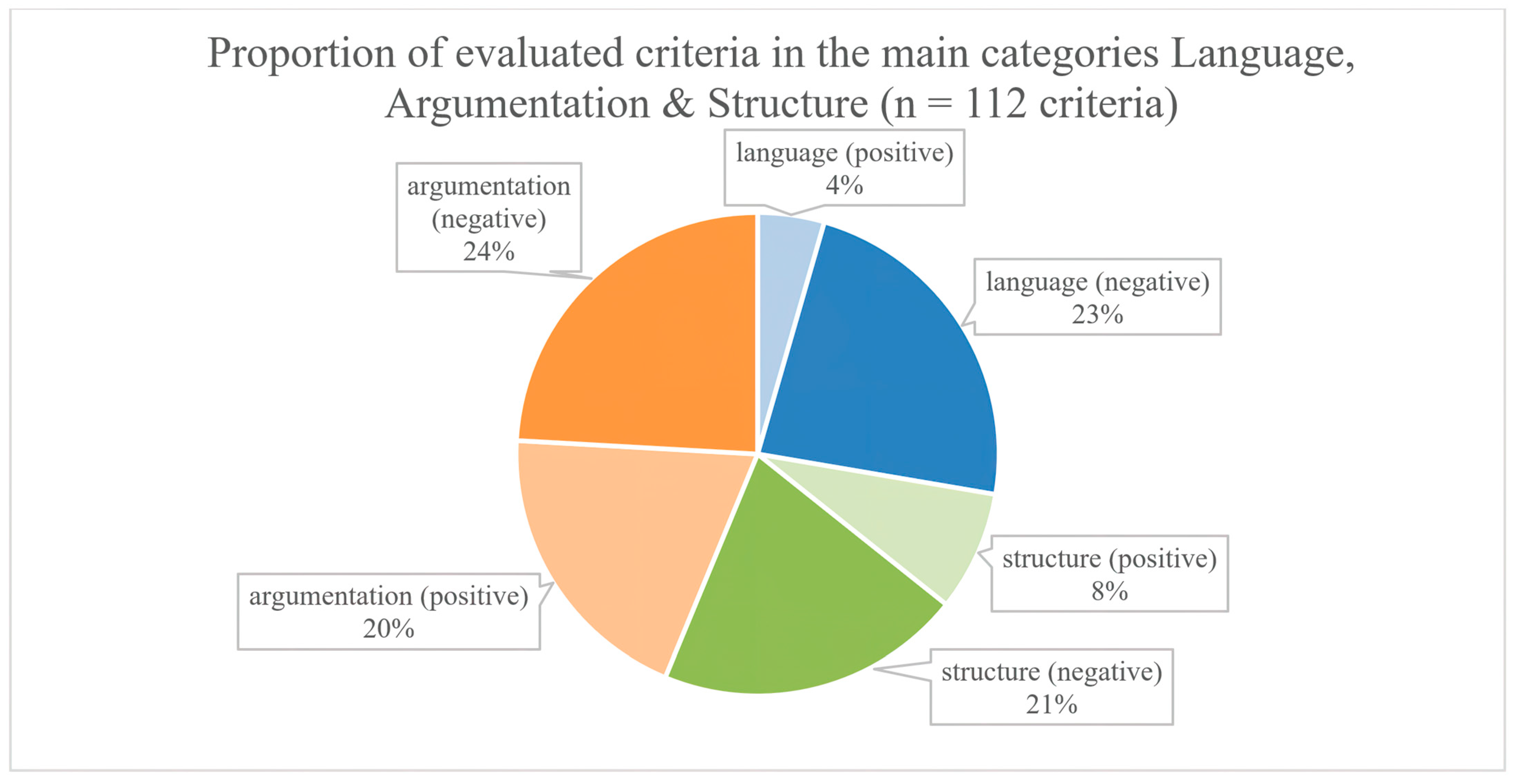

5.2. Conception of the Diagnostic Evaluation

5.2.1. Recording Performance

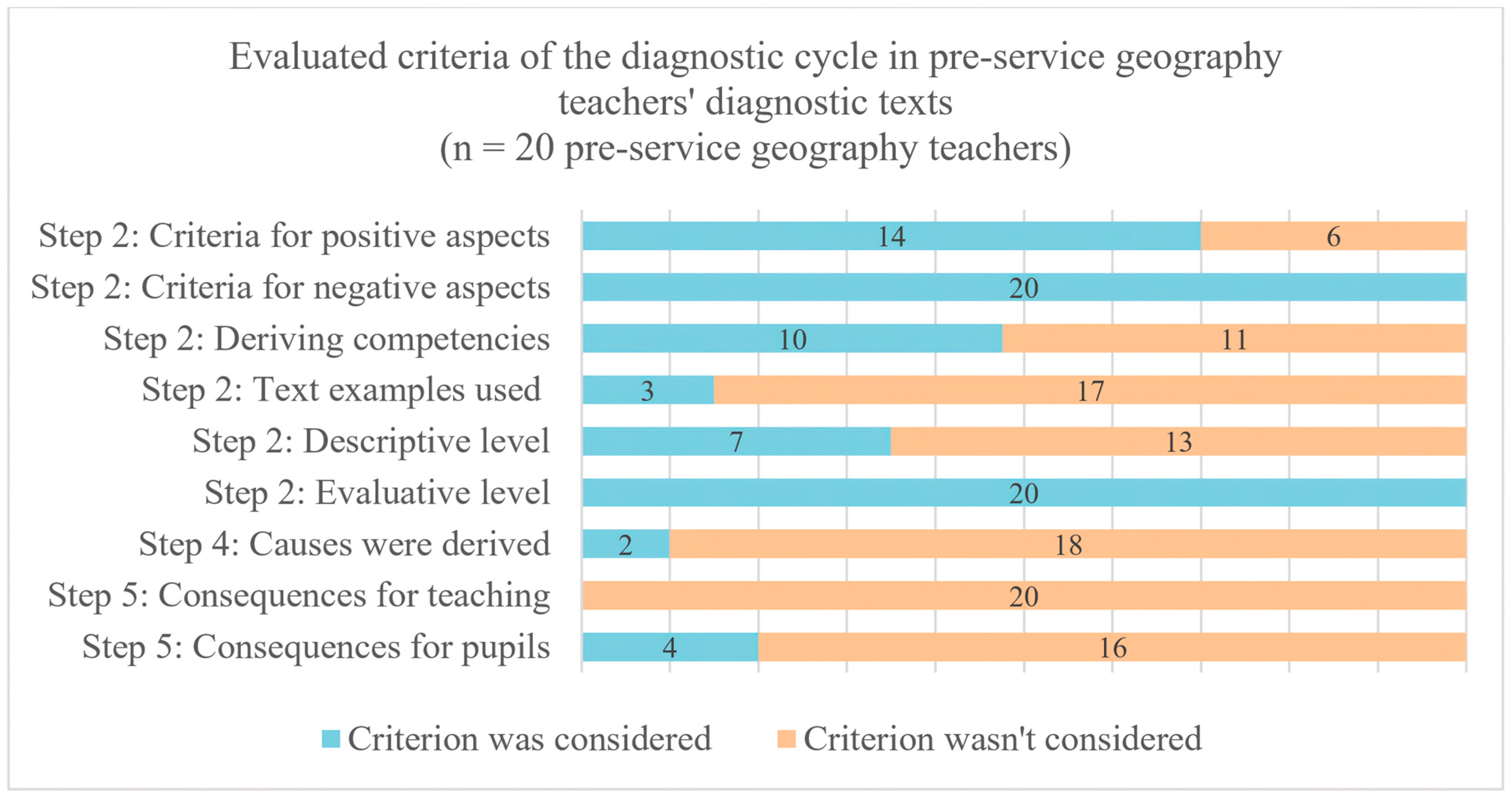

5.2.2. Analyzing and Interpreting Competencies, Clarifying Causes and Formulating Consequences

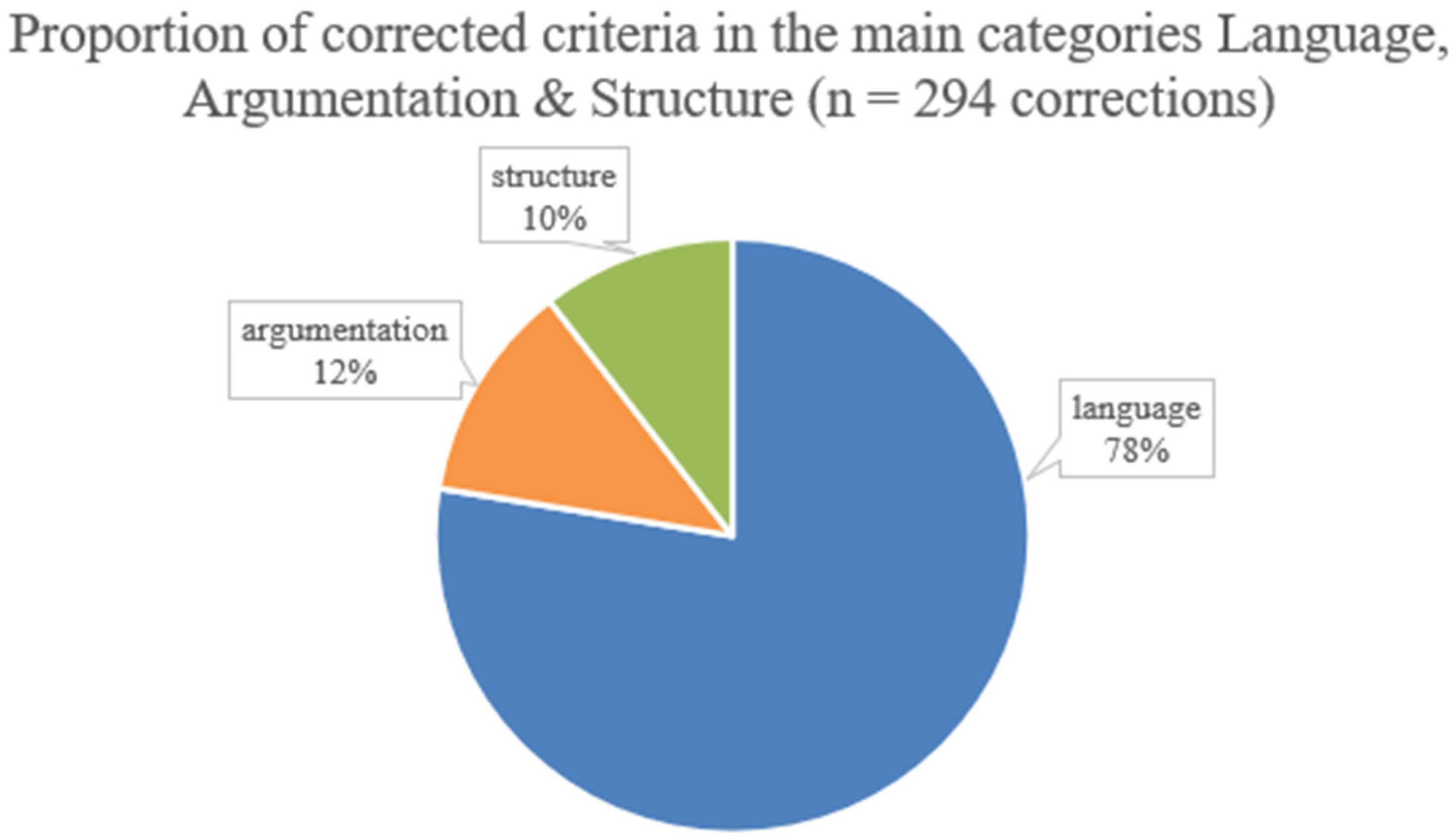

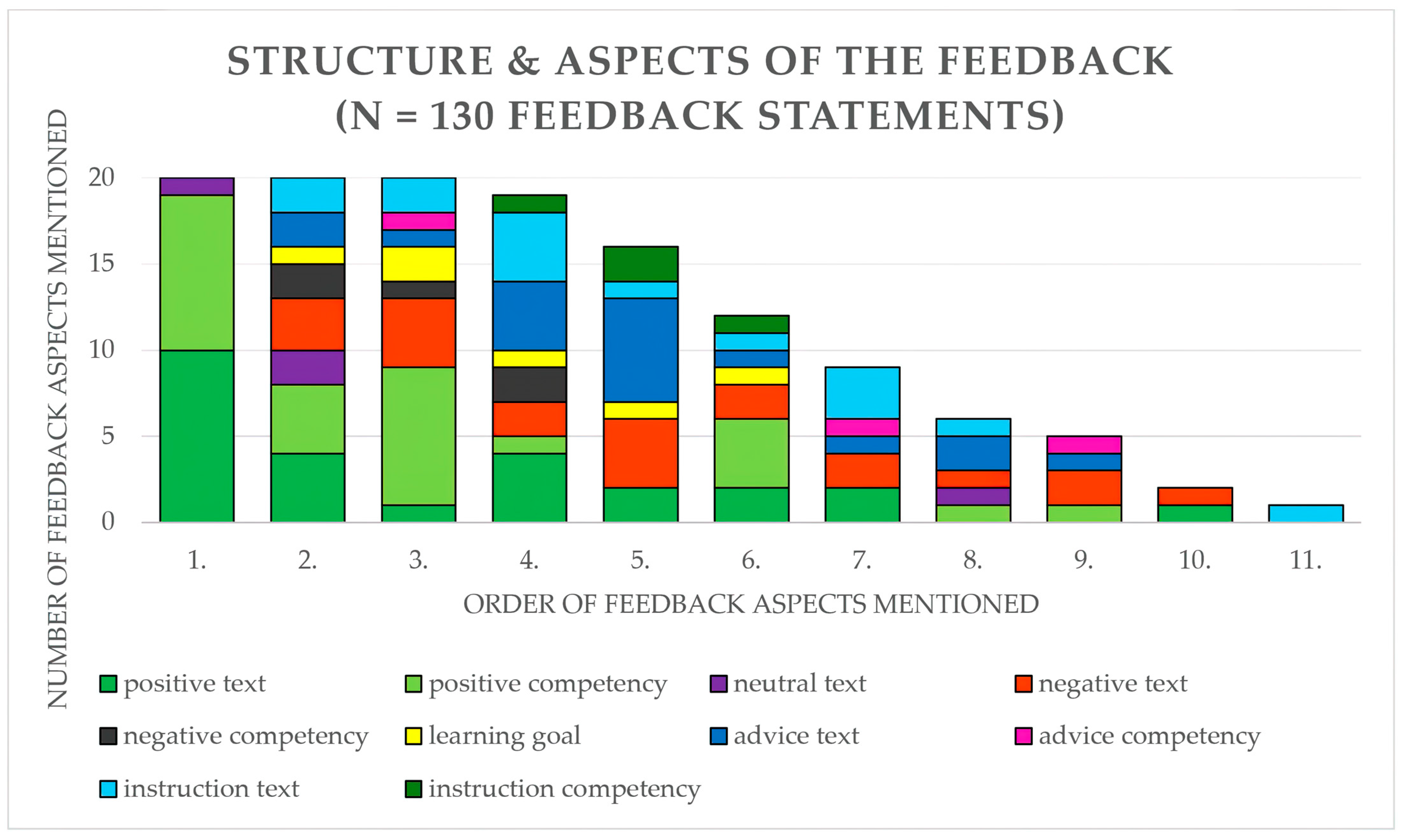

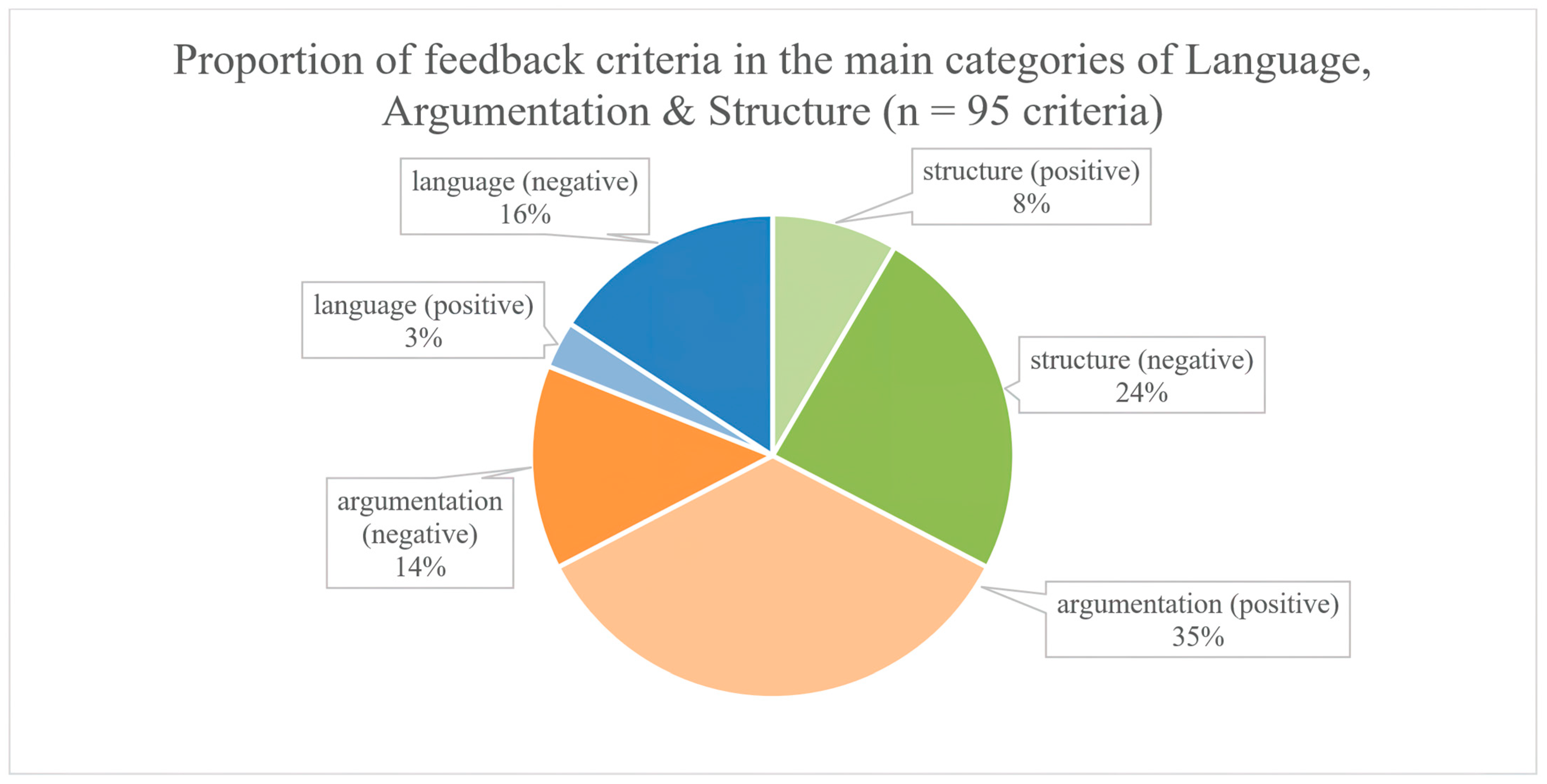

5.3. Design of the Feedback

“You’re representing the citizens’ side, if I‘ve got that right. Therefore, next time I would mention the citizens’ arguments at the end, because the many minor objections from the soccer club that you have mentioned almost make you lose sight of the arguments from the citizens’ side, although I think the arguments are strong and that you have picked them out well. Animals, nature, loss of local recreation are good arguments. If you had mentioned these after you had mentioned the footballers’ arguments, the FC’s arguments would have already been plausibly refuted” (respondent 12).

6. Discussion

Methodological Criticism and Limitations of the Study

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Budke, A.; Uhlenwinkel, A. Argumentieren im Geographieunterricht—Theoretische Grundlagen und unterrichtspraktische Umsetzungen. In Geographische Bildung. Kompetenzen in der Didaktischen Forschung und Schulpraxis; Meyer, C., Henry, R., Stöber, G., Eds.; Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin: Braunschweig, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Budke, A.; Kuckuck, M. (Eds.) Sprache im Geographieunterricht. In Sprache im Geographieunterricht. Bilinguale und Sprachsensible Materialien und Methoden; Waxmann: Münster, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 7–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dittrich, S. Argumentieren als Methode zur Problemlösung: Eine Unterrichtsstudie zur Mündlichen Argumentation von Schülerinnen und Schülern in Kooperativen Settings im Geographieunterricht. 2017. Available online: https://geographiedidaktische-forschungen.de/wp-content/uploads/gdf_65_dittrich.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Budke, A.; Meyer, M. Fachlich argumentieren lernen—Die Bedeutung der Argumentation in den unterschiedlichen Schulfächern. In Fachlich Argumentieren Lernen. Didaktische Forschungen zur Argumentation in den Unterrichtsfächern; Budke, A., Kuckuck, M., Meyer, M., Schäbitz, F., Schlüter, K., Weiss, G., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zohar, A.; Nemet, F. Fostering students’ knowledge and argumentation skills through dilemmas in human genetics. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2002, 39, 35–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, W.A.; Millwood, K.A. The Quality of Students’ Use of Evidence in Written Scientific Explanations. Cogn. Instr. 2005, 23, 23–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, V.; Clark, D. Assessment of the Ways Students Generate Arguments in Science Education: Current Perspectives and Recommendations for Future Directions. Sci. Educ. 2008, 92, 447–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aufschnaiter, C.V.; Erduran, S.; Osborne, J.; Simon, S. Arguing to learn and learning to argue: Case studies of how students’ argumentation relates to their scientific knowledge. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2008, 45, 101–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hußmann, S.; Selter, C. Diagnose und Individuelle Förderung in der MINT-Lehrerbildung: Das Projekt DortMINT; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Steingrübl, S.; Budke, A. Beurteilung argumentativer Schüler*innentexte durch Geographielehrkräfte. Zisch Z. Interdiszip. Schreib. 2023, 9, 69–100. [Google Scholar]

- Aufschnaiter, C.V.; Münster, C.; Beretz, A.-K. Zielgerichtet und differenziert diagnostizieren. MNU J. 2018, 71, 382–387. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, M. Geography through Enquiry: Approaches to Teaching and Learning in the Secondary School; Geographical Association: Sheffield, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Härmä, K.; Kärkkäinen, S.; Jeronen, E. The Dramatic Arc in the Development of Argumentation Skills of Upper Secondary School Students in Geography Education. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, L.R.D. The Role of Argumentation in the Building of Concepts of Territory and Citizenship. In Geographical Reasoning and Learning. International Perspectives on Geographical Education; Vanzella Castellar, S.M., Garrido-Pereira, M., Moreno Lache, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budke, A. Stärkung von Argumentationskompetenzen im Geographieunterricht—Sinnlos, unnötig und zwecklos? In Sprache im Fach; Becker-Mrotzek, M., Schramm, K., Thürmann, E., Vollmer, H., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2013; pp. 353–364. [Google Scholar]

- Weinert, F.E. Vergleichende Leistungsmessungen in Schulen—Eine umstrittene Selbstverständlichkeit. In Leistungsmessungen in Schulen; Weinert, F.E., Ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany; Basel, Switzerland, 2001; pp. 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Budke, A.; Schiefele, U.; Uhlenwinkel, A. Entwicklung eines Argumentationskompetenzmodells für den Geographieunterricht. Geogr. Didakt/J. Geogr. Educ. 2010, 38, 180–190. [Google Scholar]

- Morawski, M.; Budke, A. How Digital and Oral Peer Feedback Improves High School Students’ Written Argumentation—A Case Study Exploring the Effectiveness of Peer Feedback in Geography. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budke, A.; Creyaufmüller, A.; Kuckuck, M.; Meyer, M.; Schlüter, K.; Weiss, G. Argumentationsrezeptionskompetenzen im Vergleich der Fächer Geographie, Biologie und Mathematik. In Fachlich Argumentieren Lernen. Didaktische Forschungen zur Argumentation in den Unterrichtsfächern; Budke, A., Kuckuck, M., Meyer, M., Schäbitz, F., Schlüter, K., Weiss, G., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2015; pp. 273–297. [Google Scholar]

- Driver, R.; Newton, P.; Osborne, J. Establishing the norms of scientific argumentation in classrooms. Sci. Educ. 2000, 84, 287–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpudewan, M.; Roth, W.M.; Sinniah, D. The role of green chemistry activities in fostering secondary school’s understanding of acid-base concepts and argumentation skills. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2016, 17, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balgopal, M.; Wallace, A.; Dahlberg, S. Writing from different cultural contexts: How college students frame an environmental SSI through written arguments. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2017, 54, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrami, P.; Bernard, R.M.; Borokhovski, E.; Wade, A.; Surkes, M.A.; Tamim, R.; Zhang, D. Instructional interventions affecting critical thinking skills and dispositions. Rev. Educ. Res. 2008, 78, 1102–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangert-Drowns, R.L.; Hurley, M.M.; Wilkinson, B. The effects of school-based writing to learn interventions on academic achievement: A Meta-Analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 29–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.; Prior, P.; Bilbro, R.; Peake, K.; See, B.H.; Andrews, R. A reflexive approach to interview data in an investigation of argument. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2008, 31, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.; Mejia Arauz, R. Toward dialogue in the classroom: Learning and Teaching through Inquiry. J. Learn. Sci. 2006, 15, 379–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajmel, T. Wortschatzarbeit im mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Unterricht. ide 2011, 35, 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Feser, M.S.; Höttecke, D. Wie Physiklehrkräfte Schülertexte beurteilen—Instrumententwicklung. In Implementation Fachdidaktischer Innovation im Spiegel von Forschung und Praxis; Maurer, C., Ed.; Gesellschaft für Didaktik der Chemie und Physik Jahrestagung: Zürich, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, H.; Ralle, B. Diagnostik und Förderung fachsprachlicher Kompetenzen im Chemieunterricht. In Sprache im Fach. Sprachlichkeit und Fachliches Lernen; Becker-Mrotzek, M., Schramm, K., Thürmann, E., Vollmer, H.J., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 277–294. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, G.; Gorbandt, E.; Mäsgen, J.; Wiktorin, D. Zwischen Materialschlacht und Reproduktion—Schriftliche Zentralabituraufgaben im Bundesländervergleich und erste Erkenntnisse zu Schülerleistungen. Geogr. Sch. 2013, 35, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Toulmin, S. Der Gebrauch von Argumenten, 2nd ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Feilke, H.; Lehnen, K.; Rezat, S.; Steinmetz, M. Materialgestütztes Schreiben Lernen: Grundlagen, Aufgaben, Materialien; Westermann Schroedel: Braunschweig, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Quasthoff, U.; Domenech, M. Theoriegeleitete Entwicklung und Überprüfung eines Verfahrens zur Erfassung von Textqualität (TexQu) am Beispiel argumentativer Briefe in der Sekundarstufe I. Didakt. Dtsch. 2016, 21, 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rüede, C.; Weber, C. Keine Diagnose ohne Auseinandersetzung mit Form, Inhalt und Hintergrund von Schülertexten. In Beiträge zum Mathematikunterricht 2009: Vorträge auf der 43. Tagung für Didaktik der Mathematik; Neubrand, M., Ed.; WTM Verlag: Münster, Germany, 2009; pp. 819–822. [Google Scholar]

- Schrader, F.-W. Lehrer als Diagnostiker. In Handbuch der Forschung zum Lehrerberuf; Terhart, E., Bennewitz, H., Rothland, M., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2011; pp. 683–698. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, B. Diagnostik—Zur Einführung in das Schwerpunktthema. Z. Didakt. Gesellschaftswissenschaften 2016, 6, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, S. Heterogenität im Geographieunterricht. Handlungs- und Wahrnehmungsmuster von GeographielehrerInnen in Nordrhein-Westfalen; HGD: Münster, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ohl, U.; Mehren, M. Diagnose—Grundlage gezielter Förderung im Geographieunterricht. Geogr. Aktuell Sch. 2016, 36, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ophuysen, S.V.; Lintorf, K. Pädagogische Diagnostik im Schulalltag. In Lernen in Vielfalt. Chance und Herausforderung für Schul- und Unterrichtsentwicklung; Herausgeber, A., Herausgeber, B., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Helmke, A.; Hosenfeld, I.; Schrader, F.-W. Diagnosekompetenz in Ausbildung und Beruf entwickeln. Karlsruher Pädagogische Beiträge 2003, 55, 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Walz, M.; Roth, J. Professionelle Kompetenzen angehender Lehrkräfte erfassen—Zusammenhänge zwischen Diagnose-, Handlungs- und Reflexionskompetenz. In Beiträge zum Mathematikunterricht 2017; Kortenkamp, U., Kuzle, A., Eds.; WTM: Münster, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Helmke, A. Unterrichtsqualität und Lehrerprofessionalität: Diagnose, Evaluation und Verbesserung des Unterrichts; Kallmeyer und Klett: Seelze, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, U. Formative Assessment—Ein erfolgversprechendes Konzept zur Reform von Unterricht und Leistungsmessung? Z. Erzieh. 2010, 13, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, A.; Experten- und Novizen-Feedback in der Domäne Schreiben. Leseforum. 2014. Available online: https://www.leseforum.ch/sysModules/obxLeseforum/Artikel/524/2014_3_Sturm.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Klieme, E.; Warwas, J. Konzepte der individuellen Förderung. Z. Pädagogik 2011, 57, 805–818. [Google Scholar]

- Biaggi, S.; Krammer, K.; Hugener, I. Vorgehen zur Förderung der Analysekompetenz in der Lehrerbildung mit Hilfe von Unterrichtsvideos—Erfahrungen aus dem ersten Studienjahr. Seminar 2013, 2, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hattie, J. Visible Learning. A Synthesis of over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baumert, J.; Kunter, M. Stichwort: Professionelle Kompetenz von Lehrkräften. Z. Erzieh. 2006, 9, 469–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beretz, A.-K. Diagnostische Prozesse von Studierenden des Lehramts. Eine Videostudie in den Fächern Physik und Mathematik. In Studien zum Physik- und Chemielernen; Hopf, M., Niedderer, H., Ropohl, M., Sumfleth, E., Eds.; Logos: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlhauf, L.; Rutke, U.; Neuhaus, B. Entwicklung eines Kompetenzmodells zum biologischen Beobachten ab dem Vorschulalter. Z. Didakt. Naturwissenschaften 2011, 17, 203–222. [Google Scholar]

- Dudenredaktion. (o. J.). Korrektur. Auf Duden Online. Available online: https://www.duden.de/rechtschreibung/Korrektur (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Ferris, D. Does error feedback help student writers? New evidence on the short- and long-term effects of written error correction. In Feedback in Second Language Writing: Contexts and Issues; Hyland, K., Hyland, F., Eds.; Cambridge Applied Linguistics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitchener, J.; Knoch, U. The value of written corrective feedback for migrant and international students. Lang. Teach. Res. 2008, 12, 409–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, T. Leitfaden Korrektur und Bewertung: Schülertexte Besser und Effizient Korrigieren; Kallmeyer und Klett: Hannover, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rijlaarsdam, G.; Braaksma, M.; Couzijn, M.; Janssen, T.; Raedts, M.; Van Steendam, E.; Toorenaar, A.; Van den Bergh, H. Observation of peers in learning to write. Practise and research. J. Writ. Res. 2008, 1, 53–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, J.; Lehnen, K.; Rezat, S.; Schindler, K. Schriftliches Beurteilen lernen. In Schreibarrangements für Schule, Hochschule, Beruf; Bräuer, G., Schindler, K., Eds.; Fillibach: Freiburg i. Br., Germany, 2011; pp. 221–239. [Google Scholar]

- Muth, L. Einfluss der Auswertephase von Experimenten im Physikunterricht: Ergebnisse Einer Interventionsstudie zum Zuwachs von Fachwissen und Experimenteller Kompetenz von Schülerinnen und Schülern; Logos-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Klug, J.; Bruder, S.; Kelava, A.; Spiel, C.; Schmitz, B. Diagnostic competence of teachers: A process model that accounts for diagnosing learning behavior tested by means of a case scenario. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2013, 30, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J. Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximizing Impact on Learning; Routledge Chapman/Hall: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyi, S.R.; Homoki, E. Comparative analysis of the methods of teaching geography in different types of schools. J. Appl. Tech. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.; McKeown, D.; Kiuhara, S.; Harris, K.R. A meta-analysis of writing instruction for students in the elementary grades. J. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 104, 879–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, J.M.; Timperley, H.S. Feedback to writing, assessment for teaching and learning and student progress. Assess. Writ. 2010, 15, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, A.; Beurteilen und Kommentieren von Texten als Fachdidaktisches Wissen. Leseräume. 2016. Available online: https://leseräume.de/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/lr-2016-1-sturm_115-132.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Bouwer, R.; Béguin, A.; Sanders, T.; van den Bergh, H. Effect of genre on the generalizability of writing scores. Lang. Test. 2015, 32, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steingrübl, S.; Budke, A. Konzeption und Evaluation einer Open Educational Ressource (OER) zur sprachlichen Förderung von Schülerinnen beim argumentativen Schreiben im Geographieunterricht im Kontext der Lehrerinnenbildung. Herausford. Lehrerinnenbildung—Z. Konzept. Gestalt. Diskuss. 2022, 5, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacher, W. Leistung Entwickeln, Überprüfen und Beurteilen; Klinkhardt: Heilbronn, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rupp, A.A.; Leucht, M.; Hartung, R. “Die Kompetenzbrille aufsetzen”. Verfahren zur multiplen Klassifikation von Lernenden für Kompetenzdiagnostik. Unterricht und Testung. Unterrichtswissenschaft 2006, 3, 195–219. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, K.A.; Hany, E.A. Standardisierte Schulleistungsmessungen. In Leistungsmessungen in Schulen; Weinert, F.E., Ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2001; pp. 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, D.; Balderstone, D. Learning to Teach Geography in the Secondary School, 2nd ed.; A Companion to School Experience; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Swift, D. Meeting Special Educational Needs in the Curriculum: Geography; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur, C.A. Instruction in evaluation and revision. In Handbook of Writing Research; MacArthur, C.A., Graham, S., Fitzgerald, J., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Myhill, D.; Jones, S.; Watson, A. Grammar matters: How teachers’ grammatical knowledge impacts on the teaching of writing. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2013, 36, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; MacArthur, C. Student revision with peer and expert reviewing. Learn. Instr. 2010, 20, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yotham, T.; Ndabi, J. Teachers’ Feedback Provision Practices: A Case of Geography Subject Continuous Assessment Activities in Tanzanian Secondary Schools. Pap. Educ. Dev. 2023, 41, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, M.S.; PytlikZillig, L.M.; Bruning, R.H. Helping preservice teachers learn to assess writing: Practice and feedback in a Web-based environment. Assess. Writ. 2009, 14, 38–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, H. Diagnostische Kompetenz von Mathematik-Lehramtsstudierenden. Messung und Förderung; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Andriessen, J. Arguing to learn. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences; Sawyer, R.K., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 443–459. [Google Scholar]

- Berland, L.K.; Reiser, B.J. Classroom Communities’ Adaptations of the Practice of Scientific Argumentation. Sci. Educ. 2010, 95, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasley, S.D.; Roschelle, J. Constructing a joint problem space: The computer as a tool for sharing knowledge. In Computers as Cognitive Tools; Lajoie, S.P., Derry, S.J., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1993; pp. 229–258. [Google Scholar]

- Morawski, M.; Budke, A. Förderung von Argumentationskompetenzen durch das “Peer-Review-Verfahren”? In Argumentieren im Sprachunterricht. Beiträge zur Fremdsprachenvermittlung. Sonderheft 26; Massud, A., Ed.; bzf: Landau, Germany, 2018; pp. 75–101. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken; 12., aktual., überarb. Aufl.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage, M. Formative Assessment: What do teachers need to know and do? Phi Delta Kappan 2007, 89, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavelson, R.J.; Young, D.B.; Ayala, C.C.; Brandon, P.R.; Furtak, E.M.; Ruiz-Primo, M.A.; Yin, Y. On the impact of curriculum-embedded formative assessment on learning: A collaboration between curriculum and assessment developers. Appl. Meas. Educ. 2008, 21, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwer, R.; van den Bergh, H. Effectiveness of teacher feedback. In Proceedings of the EARLI SIG Conference on Writing Research, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 27–29 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Budke, A.; Weiss, G. Sprachsensibler Geographieunterricht. In Sprache als Lernmedium im Fachunterricht. Theorien und Modelle für das Sprachbewusste Lehren und Lernen; Michalak, M., Ed.; Schneider Hohengrehen: Baltmannsweiler, Germany, 2014; pp. 113–133. [Google Scholar]

| Model Criteria | Guiding Questions for Evaluation |

|---|---|

| 1 Recording performance | The pre-service teacher has… [ ] text-immanent corrections [ ] side comments [ ] Other which shows that they have reviewed the text product and recorded the pupils’ performance [10,49]. |

| These were formulated [ ] comprehensibly [ ] incomprehensibly [10,49]. | |

| 2 Analyzing & interpreting competencies | In the diagnostic judgment, the pre-service teacher has … [10,49]. [ ] used criteria of good reasoning to identify positive aspects. [ ] used criteria of good reasoning to identify deficient aspects. [ ] identified competencies. [ ] used text examples to support their evaluation. [ ] listed a descriptive and an evaluative perspective [34]. |

| In the diagnostic evaluation, the pre-service teacher has… ____ linguistic criteria. ____ argumentative criteria. ____ structural criteria [10]. | |

| 3 Giving feedback | In the feedback, the pre-service teacher… [ ] used a direct address [54]. [ ] used empty phrases 1 [54,63,72]. [ ] made textual references [54]. [ ] formulated dialogically [ ] directive 2 [63,71,84]. [ ] focused positive [ ] negative aspects [54]. [ ] focused local [ ] global text level 3 [63]. [ ] described a summarized evaluation of pupil performance [56]. |

| The pre-service teacher has named types of errors/criteria in the feedback _____ (number). | |

| 4 Clarifying causes | In the diagnostic judgment, the pre-service teacher has … [49] [ ] derived possible causes for the pupils’ abilities. [ ] derived no causes. |

| The derived causes are … [49] [ ] situation-specific. [ ] learner-specific. [ ] subject-specific. | |

| The derived causes are… [ ] plausible against the background of the skills analysis [49]. [ ] implausible against the background of the skills analysis. | |

| 5 Drawing consequences | The pre-service teacher has derived from the diagnostic evaluation… [ ] no consequences. [ ] consequences for the individual support of the pupil [49]. [ ] consequences for teaching [49,57]. |

| The derived consequences for support are… [ ] suitable for the deficits & causes [49]. [ ] unsuitable for the deficits & causes. |

| Feedback Styles | Description | Positive vs. Negative Focus | Text vs. Competency Orientation | Advice vs. Instructions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advising | Makes concrete suggestions for improving the text and competencies in a dialogical manner. The wording and focus are positive. Praise is often encouraging at the beginning and again at the end of the feedback. | positive | both | advice |

| Criticizing | Emphasizes mainly negative aspects and criticizes. This can be related to the text and competencies. No advice is formulated, but instructions are given if at all. | negative | both | (instructions) |

| Instructing | Formulates direct instructions to be followed up and emphasizes negative aspects for his explanation. This can be related to the text and the competencies. | both | both | instructions |

| Balancing | Balances positive and negative aspects at text level. These are presented alternately and there is hardly any tendency to summarize the assessment. An attempt is made to evaluate performance holistically and objectively. | both | text | both/nothing |

| Supporting | Focuses on both negative and positive aspects, particularly in relation to competencies. Learning objectives are linked and support options are considered. | both | competency | Rather advice |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Steingrübl, S.; Budke, A. Diagnostic and Feedback Behavior of German Pre-Service Teachers Regarding Argumentative Pupils’ Texts in Geography Education. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 919. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080919

Steingrübl S, Budke A. Diagnostic and Feedback Behavior of German Pre-Service Teachers Regarding Argumentative Pupils’ Texts in Geography Education. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(8):919. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080919

Chicago/Turabian StyleSteingrübl, Saskia, and Alexandra Budke. 2024. "Diagnostic and Feedback Behavior of German Pre-Service Teachers Regarding Argumentative Pupils’ Texts in Geography Education" Education Sciences 14, no. 8: 919. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080919

APA StyleSteingrübl, S., & Budke, A. (2024). Diagnostic and Feedback Behavior of German Pre-Service Teachers Regarding Argumentative Pupils’ Texts in Geography Education. Education Sciences, 14(8), 919. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080919