COVID-19 and Digital Transformation in Higher Education Institutions: Towards Inclusive and Equitable Access to Quality Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To identify effective strategies and lessons learned from the global COVID-19 pandemic experience to leverage digital technologies and promote inclusive and equitable access to quality education in HEIs.

- To identify and analyze the key lessons learned from the challenges faced by HEIs in implementing digital transformation to ensure inclusive and equitable access to quality education during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Conceptual Framework

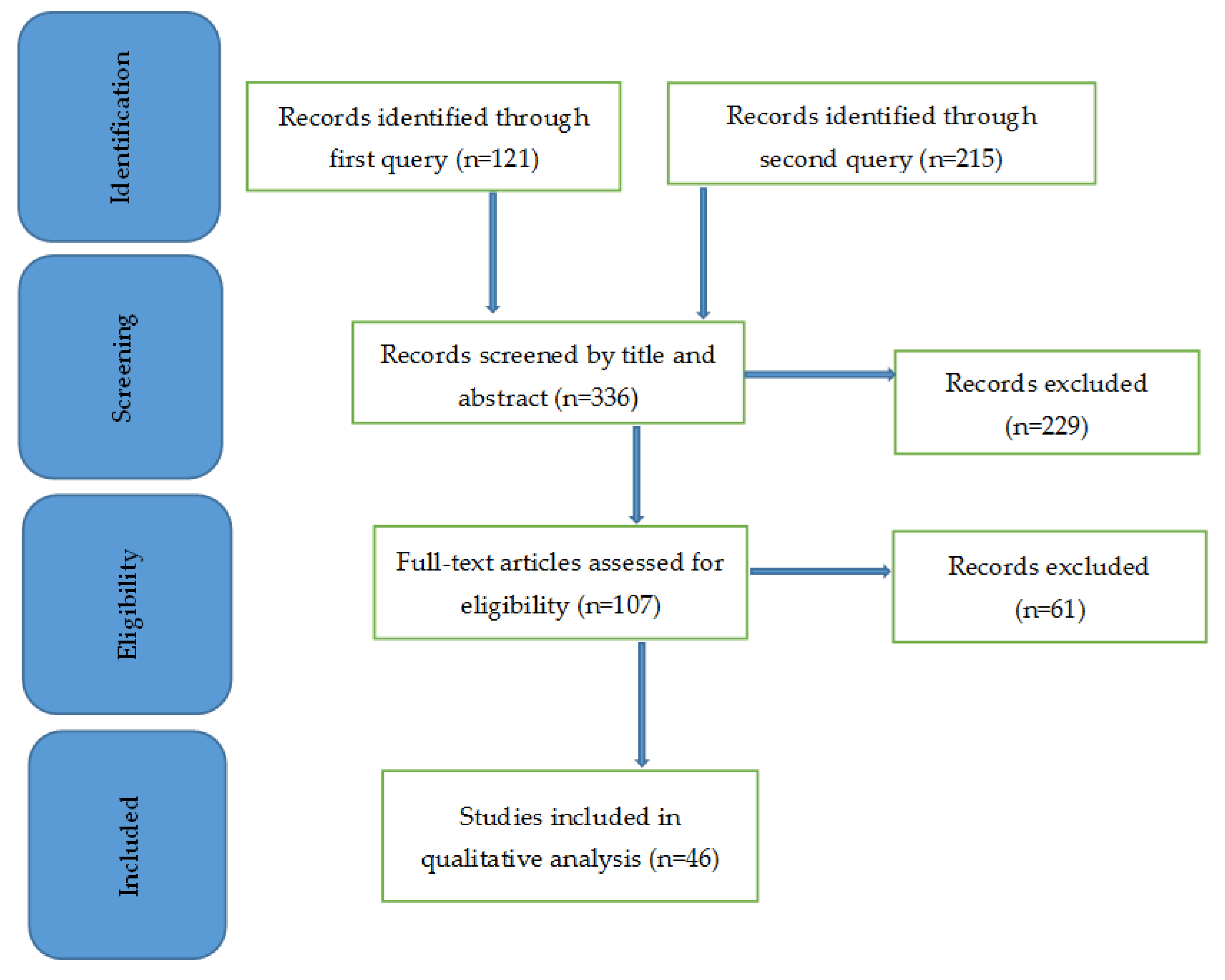

3. Methods

- RQ1: What lessons have been learned from the effective strategies that HEIs have employed to leverage digital technologies in promoting inclusive and equitable access to quality education during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- RQ2: What lessons have been learned from the challenges that HEIs faced in implementing digital transformation to ensure inclusive and equitable access to quality education during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Discuss the advantages, benefits, or opportunities of digital transformation in higher education in the era of COVID-19.

- Address issues, problems, obstacles, challenges, or barriers that faced digital transformation within higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Be in the English language.

- Be published between 2020 and 2023—this timeframe corresponds to the onset of suspended in-person classes in many parts of the world due to COVID-19 and the period during which the present study was conducted.

4. Results

4.1. RQ1: What Lessons Have Been Learned from the Effective Strategies That HEIs Have Employed to Leverage Digital Technologies in Promoting Inclusive and Equitable Access to Quality Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic?

4.1.1. Inclusivity

4.1.2. Equity

4.1.3. Quality

4.2. RQ2: What Lessons Have Been Learned from the Challenges That HEIs Faced in Implementing Digital Transformation to Ensure Inclusive and Equitable Access to Quality Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic?

Digital Divide and Inequality

5. Discussion, Conclusions, and Recommendations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berchin, I.I.; de Andrade, J.B.S.O. GAIA 3.0: Effects of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on sustainable development and future perspectives. Res. Glob. 2020, 2, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Garavaglia, A. Teaching and learning after the COVID-19 pandemic: A reflection on the challenges and opportunities. Res. Educ. Media 2022, 14, i–ii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdrasheva, D.; Escribens, M.; Sabzalieva, M.; do Nascimento, V.D.M.; Verano, Y.C.A. Resuming or Reforming? Tracking the Global Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Higher Education after Two Years of Disruption; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mseleku, Z. A literature review of e-learning and e-teaching in the era of COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2020, 5, 588–597. Available online: https://www.ijisrt.com/assets/upload/files/IJISRT20OCT430.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- UNESCO. Supporting Teachers and Education Personnel during Times of Crisis; UNESCO Digital Library: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, P. The Impact of COVID-19: How Are Universities Three Years after the Pandemic? UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Acosta, P. COVID-19 pandemic: Shifting digital transformation to a high-speed gear. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2020, 37, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.G.; Vogel, A.; Ulber, M. Digitalizing higher education in light of sustainability and rebound effects: Surveys in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. Manag. Digit. Transform. 2021, 28, 13–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Salvia, A.L.; Beynaghi, A.; Fritzen, B.; Ulisses, A.; Avila, L.V.; Vasconcelos, C.R.; Moggi, S.; Mifsud, M.; Anholon, R. Digital transformation and sustainable development in higher education in a post-pandemic world. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2023, 31, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, C.; McCormack, M. Driving Digital Transformation in Higher Education; EDUCAUSE: Louisville, CO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Quy, V.K.; Thanh, B.T.; Chehri, A.; Linh, D.M.; Tuan, D.A. AI and digital transformation in higher education: Vision and approach of a specific university in Vietnam. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.C.; Diep, Q.B. Technological spotlights of digital transformation in tertiary education. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 40954–40966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaputa, V.; Loučanová, E.; Tejerina-Gaite, F.A. Digital transformation in higher education institutions as a driver of social oriented innovations. Soc. Innov. High. Educ. 2022, 61, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.; Gómez, B.; Binjaku, K.; Meçe, E.K. Digital transformation initiatives in higher education institutions: A multivocal literature review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 12351–12382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.; Horta, H.; Postiglione, G.A. Living in uncertainty: The COVID-19 pandemic and higher education in Hong Kong. Stud. High. Educ. 2021, 46, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarts, H.; Greijn, H.; Mohamedbhai, H.; Jowi, O.J. The SDGs and African higher education. In Africa and the Sustainable Development Goals; Ramutsindela, M., Mickler, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 231–242. [Google Scholar]

- Trevisan, L.V.; Eustachio, J.H.P.P.; Dias, B.G.; Leal Filho, W.; Pedrozo, E.Á. Digital transformation towards sustainability in higher education: State-of-the-art and future research insights. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 2789–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United-Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ufua, D.E.; Emielu, E.T.; Olujobi, O.J.; Lakhani, F.; Borishade, T.T.; Ibidunni, A.S.; Osabuohien, E.S. Digital transformation: A conceptual framing for attaining sustainable development goals 4 and 9 in Nigeria. J. Manag. Organ. 2021, 27, 836–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, B.R.; Ferdiana, R.; Kusumawardani, S.S. The study of the barriers to digital transformation in higher education: A preliminary investigation in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 2020 6th International Conference on Science and Technology (ICST), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 7–8 September 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Benavides, L.M.C.; Arias, T.J.A.; Serna, A.M.D.; Bedoya, B.J.W.; Burgos, D. Digital transformation in higher education institutions: A systematic literature review. Sensors 2020, 20, 3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roshid, M.M.; Sultana, S.; Kabir, M.M.N.; Jahan, A.; Khan, R.; Haider, M.Z. Equity, fairness, and social justice in teaching and learning in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, B.R.; Ferdiana, R.; Kusumawardani, S.S. Barriers to digital transformation in higher education: An interpretive structural modeling approach. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2021, 18, 2150024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkrimpizi, T.; Peristeras, V.; Magnisalis, I. Classification of barriers to digital transformation in higher education institutions: Systematic literature review. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, S.; Cresswell, K.; Robertson, A.; Huby, G.; Avery, A.; Sheikh, A. The case study approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmi, J. Impact of COVID-19 on higher education from an equity perspective. Int. High. Educ. 2021, 105, 5–7. Available online: https://ejournals.bc.edu/index.php/ihe/article/view/14367 (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Woldegiorgis, E.T. Mitigating the digital divide in the South African higher education system in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Perspect. Educ. 2022, 40, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichardo, J.I.; López-Medina, E.F.; Mancha-Cáceres, O.; González-Enríquez, I.; Hernández-Melián, A.; Blázquez-Rodríguez, M.; Jiménez, V.; Logares, M.; Carabantes-Alarcon, D.; Ramos-Toro, M.; et al. Students and teachers using mentimeter: Technological innovation to face the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and post-pandemic in higher education. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Grounded theory methods in social justice research. Strateg. Qual. Inq. 2011, 4, 359–380. [Google Scholar]

- Pijanowski, J.C.; Brady, K.P. Defining social justice in education. In Handbook of Social Justice Interventions in Education; Mullen, C.A., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, S.; Czerniewicz, L. Approaches to open education and social justice research. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2020, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, J.; D’Addio, A. Policies for achieving inclusion in higher education. Policy Rev. High. Educ. 2021, 5, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Brereton, O.P.; Budgen, D.; Turner, M.; Bailey, J.; Linkman, S. Systematic literature reviews in software engineering: A systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2009, 51, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocaña-Zúñiga, C.L.; Tineo, M.; Fernandez-Zarate, F.H.; Quiñones-Huatangari, L.; Huaccha-Castillo, A.E.; Morales-Rojas, E.; Miguel-Miguel, H.W. Implementing the sustainable development goals in university higher education: A systematic review. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2023, 18, 1769–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, N.S. The significance of digital learning for sustainable development in the post-COVID19 world in Saudi Arabia’s higher education institutions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazlan, N.A.S.; Nawawi, M.N.; Saputra, J.; Muhamad, S.B.; Abdullah, R. Classification of attributes on green manufacturing practices: A systematic review. Planning 2022, 17, 1839–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanvaria, V.K.; Monika, K. Promoting equity in education: Analyzing the influence of technology-integrated faculty development on inclusive teaching practices. Res. Dialogue 2023, 2, 396–405. Available online: https://theresearchdialogue.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/42.-Dr.-Vinod-Kumar-Kanvaria-Monika.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Ausat, A.M.A. Positive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the world of education. J. Pendidik. 2022, 23, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulenga, E.M.; Marban, J.M. Is COVID-19 the gateway for digital learning in mathematics education? Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2020, 12, ep269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maketo, L.; Issa, T.; Issa, T.; Nau, S.Z. M-Learning adoption in higher education towards SDG4. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2023, 147, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banihashem, S.K.; Noroozi, O.; van Ginkel, S.; Macfadyen, L.P.; Biemans, H.J. A systematic review of the role of learning analytics in enhancing feedback practices in higher education. Educ. Res. Rev. 2022, 37, 100489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A. Equity in higher education: Evidences, policies and practices. Setting the scene. In Equity Policies in Global Higher Education: Reducing Inequality and Increasing Participation and Attainment; Tavares, O., Sá, C., Sin, C., Amaral, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cairney, P.; Kippin, S. The future of education equity policy in a COVID-19 world: A qualitative systematic review of lessons from education policymaking. Open Res. Eur. 2021, 1, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonegawa, Y. Education in SDGs: What is inclusive and equitable quality education? In Sustainable Development Disciplines for Humanity: Breaking Down the 5Ps—People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace, and Partnerships; Urata, S., Akao, K.I., Washizu, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Gateway East, Singapore, 2022; pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. The Impact of COVID-19 on Student Equity and Inclusion: Supporting Vulnerable Students during School Closures and School Re-Openings; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Metsamuuronen, J.; Lehikko, A. Challenges and possibilities of educational equity and equality in the post-COVID-19 realm in the Nordic countries. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2022, 67, 1100–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathrani, A.; Sarvesh, T.; Umer, R. Digital divide framework: Online learning in developing countries during the COVID-19 lockdown. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2022, 20, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlQashouti, N.; Yaqot, M.; Franzoi, R.E.; Menezes, B.C. Educational system resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: Review and perspective. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabaleiro-Cervino, G.; Vera, C. The impact of educational technologies in higher education. Gist Educ. Learn. Res. J. 2020, 20, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, R.; Turnbull, D.; Cowling, M.A.; Vanderburg, R.; Vanderburg, M.A. Implementing educational technology in higher education institutions: A review of technologies, stakeholder perceptions, frameworks and metrics. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 16403–16429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, F.; Tuhuteru, L.; Sampe, F.; Ausat, A.M.A.; Hatta, H.R. Analysing the role of ChatGPT in improving student productivity in higher education. J. Educ. 2023, 5, 14886–14891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamoliddinovich, U.B. Fundamentals of education quality in higher education. Int. J. Soc. Interdiscip. Res. 2022, 11, 149–151. Available online: https://gejournal.net/index.php/IJSSIR/article/view/107/85 (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Schonberger, M. ChatGPT in higher education: The good, the bad, and the University. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Higher Education Advances (HEAd’23), Valencia, Spain, 19–22 June 2023; pp. 331–338. [Google Scholar]

- Vykydal, D.; Folta, M.; Nenadál, J. A study of quality assessment in higher education within the context of sustainable development: A case study from Czech Republic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.A.; Ahmed, H. Approaches to quality education in tertiary sector: An empirical study using PLS-SEM. Educ. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 5491496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. Digital transformation to advance high-quality development of Higher Education. J. Educ. Technol. Dev. Exch. 2022, 15, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. Digital initiatives for access and quality in higher education: An overview. Prabandhan Indian J. Manag. 2020, 13, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhammadi, S. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on learning quality and practices in higher education: Using deep and surface approaches. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, K.R. Inequalities reinforced through online and distance education in the age of COVID-19: The case of higher education in Nepal. Int. Rev. Educ. 2021, 67, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tewathia, N.K.A.; IIavarasan, P.V. Social inequalities, fundamental inequalities, recurring of the digital divide: Insights from India. Technol. Soc. 2020, 61, 101251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Bridging digital divide amidst educational change for socially inclusive learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sage Open 2021, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azionya, C.M.; Nhedzi, A. The digital divide and higher education challenge with emergency online learning: Analysis of Tweets in the wake of the COVID-19 lockdown. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. TOJDE 2021, 22, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faloye, S.T.; Ajayi, N. Understanding the impact of the digital divide on South African students in higher educational institutions. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2022, 14, 1734–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magedi, M.J.; Rakgogo, T.J.; Mnguni, O.S.; Segabutla, M.H.; Kgwete, L. COVID-19 and its impact on students with disabilities: A social justice expression at a South African university. Transform. High. Educ. 2023, 8, a212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanyane, M. Digital work–transforming the higher education landscape in South Africa. In New Digital Work: Digital Sovereignty at the Work Place; Shajek, A., Hartmann, E.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Litchfield, I.S.D.; Greenfield, S. Impact of COVID-19 on the digital divide: A rapid review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e053440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzal, A.; Khan, S.; Daud, S.; Ahmad, Z.; Butt, A. Addressing the digital divide: Access and use of technology in education. J. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2023, 3, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S. The digital divide and smartphone reliance for disadvantaged students in higher education. J. Syst. Cybern. Inform. 2022, 20, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundari, K. Student access to technology at home and learning hours during COVID-19 in the U.S. Educ. Res. Policy Pract. 2023, 22, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, A.; Gabaly, S.; Morales-Alonso, G.; Urueña, A. The digital divide in light of sustainable development: An approach through advanced machine learning techniques. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 150, 119754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Kaabi, N.H.O.; Qawasmeh, F. The impact of digital divide on the quality of university education. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2020, 10, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agasisti, T.; Soncin, M. Higher education in troubled times: On the impact of COVID-19 in Italy. Stud. High. Educ. 2021, 46, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristovnik, A.; Keržič, D.; Ravšelj, D.; Tomaževič, N.; Umek, L. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on life of higher education students: A global perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.A.; Khan, M.I.; Banerjee, S.; Safi, F. A tale of online learning during COVID-19: A reflection from the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC)countries. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanthakorn, B.; Ractham, P.; Kaewkitipong, L. Double burden: Exploring the digital divide in the Burmese educational system following the 2021 coup d’etat and the COVID-19 pandemic. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2023, 11, 100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadesse, S.; Muluye, W. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on education system in developing countries: A review. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 8, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S. Inclusive and exclusive education for diverse learning needs. In Quality Education: Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P.G., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ainscow, M. Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nord. J. Stud. Educ. Policy 2020, 6, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoofman, J.; Secord, E. The effect of COVID-19 on education. Pediatr. Clin. 2021, 68, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasli, A.; Tee, M.; Lai, Y.L.; Tiu, Z.C.; Soon, E.H. Post-COVID-19 strategies for higher education institutions in dealing with unknown and uncertainties. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 992063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, S. The tricky concept of ‘educational equity’–in search of conceptual clarity. Scott. Educ. Rev. 2022, 54, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minow, M. Equality vs. equity. Am. J. Law Equal. 2021, 1, 167–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A. Focus on quality in higher education in India. Indian J. Public Adm. 2021, 67, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsetty, A.; Adams, C. Impact of the digital divide in the age of COVID-19. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2020, 27, 1147–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaimara, P. Digital transformation stands alongside inclusive education: Lessons learned from a project called “Waking Up in the Morning”. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2023, 29, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Qadri, M.A.; Suman, R. Understanding the role of digital technologies in education: A review. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2022, 3, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herckis, L.; Leiser, A. Moving from stated values to enacted efforts: Strategic leadership in higher education. In Digital Transformation of Higher Education—Global Learning Report 2022; Hesse, F.W., Kobsda, C., Schemmann, C., Eds.; Global Learning Council: Berlin, Germany, 2022; pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Moonasamy, R.A.; Naidoo, G.M. Digital learning: Challenges experienced by South African university students’ during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indep. J. Teach. Learn. 2022, 17, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domain | Definition | Source and Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusivity | Investigating how digital transformation promotes access and participation for diverse student populations. | [39] India [40] Indonesia [41] Zambia [42] Zimbabwe [13,43] Worldwide [23] Bangladesh |

| Equity | Examining how digital transformation addresses issues of fairness, justice, and equal opportunities in higher education. | [44,45,46] Worldwide [47] OECD countries [48] Nordic countries [49] India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Afghanistan |

| Quality | Assessing how digital transformation enhances the quality of teaching, learning, and student outcomes. | [15,46,50,51,52,53,54,55] Worldwide [56] Czech [57] Bangladesh [58] China [59] India [60] Kuwait |

| Digital Divide and Inequality | Analyzing how digital transformation may exacerbate digital divide and inequalities in higher education | [61] Nepal [62] India [63] China [64,65,66,67] South Africa [68] United Kingdom [69] Turkey [70,71] United States [72] Spain [73] Jordan [74] Italy [75] Worldwide [76] Pakistan, Bangladesh and India [77] Myanmar [78] Developing countries [23] Bangladesh |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matsieli, M.; Mutula, S. COVID-19 and Digital Transformation in Higher Education Institutions: Towards Inclusive and Equitable Access to Quality Education. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080819

Matsieli M, Mutula S. COVID-19 and Digital Transformation in Higher Education Institutions: Towards Inclusive and Equitable Access to Quality Education. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(8):819. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080819

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatsieli, Molefi, and Stephen Mutula. 2024. "COVID-19 and Digital Transformation in Higher Education Institutions: Towards Inclusive and Equitable Access to Quality Education" Education Sciences 14, no. 8: 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080819

APA StyleMatsieli, M., & Mutula, S. (2024). COVID-19 and Digital Transformation in Higher Education Institutions: Towards Inclusive and Equitable Access to Quality Education. Education Sciences, 14(8), 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080819