Abstract

This exploratory study analyses the level of the development of the eight key competencies in sustainability of 237 students in the 7th–10th grades, when confronted with a real conflict situation associated with the production and consumption of ‘fast fashion’. Their responses were categorised into four levels, representing the degree of development of each competence. The results reflect a low level of competence development, with no significant differences among academic year groups. The competence where the highest level of development was reached was the inter-personal competence, as students recognised that the consumption of fast fashion contributes to the labour exploitation of others. However, this did not prompt students to question the prevailing consumerist values in our society (values-thinking competence), their own practises (implementation competence), or their own contribution to the problem (intra-personal competence). Therefore, it seems necessary to address different socio-environmental issues, critically analyse our daily actions, and thus promote these competencies in sustainability in schools. These will enable students to actively participate in environmental conservation from the perspective of environmental and social justice.

1. Introduction

The current consumption model of our society, based on the continuous generation of needs for goods and services, comes with significant environmental, socio-economic, and ethical impacts [1,2]. Among the different forms of consumption, we highlight that of clothing and footwear, given that, in the last two decades, global textile manufacturing and consumption have almost doubled [3].

In particular, textile production has increased from 6 kg per capita per year in the 1970s to around 15 kg in 2020 [4]. This increase is predominantly due to the phenomenon known as ‘fast fashion’. The main trend is that followers and consumers are mostly young people who are heavily influenced by the media and social networks [5]. It is a form of textile production and consumption sustained under the premise of ‘use and throw away’ and favoured by a constant change in style, involving a greater number of collections per year and at much lower prices [6]. This form of textile production, distribution, and consumption is characterised by a linear and delocalised operation: linear because large quantities of non-renewable resources are extracted to produce clothing for very limited use. According to [7], by accelerating the rate at which new collections are generated, and by manufacturing with fragile and cheap fabrics, fast fashion limits the repair of garments, and they are even discarded before they are damaged. Turned into waste, these textiles are mainly destined for landfills or incineration [8]. According to [4], the textile industry produces 92 million tonnes of waste per year, of which less than 1% is recycled. This linear system leads to resource depletion, and pollutes and degrades the environment [8,9]. In fact, the fashion industry is considered to be the second most polluting industry on the planet, producing 8% of the total CO2 released into the atmosphere, and is one of the most water-intensive industries [10].

In addition, the industry has offshored the production and consumption of garments. In the 1990s, European and US companies started to outsource production to low-wage countries in Asia [7]. This is a clear example of the unfair distribution of the benefits of resource exploitation, as they are not destined for those who bear the risks and harms of production [11]. In practise, this delocalisation makes it difficult for consumers to be aware of and feel affected by the environmental and social impacts of textile manufacturing, as they occur in remote locations and social contexts.

This reality shows that we are facing a problem of social and environmental justice that is highly dependent on people’s individual values, attitudes, and behaviours. Therefore, the active participation of citizens, especially young people, is necessary in order to involve them in this problem. For [12], Education for Sustainability (EfS) is key and must be oriented towards critically assessing our lifestyle as well as evaluating the possibilities for change in consumption decisions based on the recognition of individual responsibility.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Young People and the Consumption of Fast Fashion

Different studies aimed at analysing the perceptions and attitudes of secondary school students regarding the socio-environmental problems associated with consumption indicate that they relate it positively to economic development and the creation of jobs but show great difficulty in recognising its connection to other conflicts, such as the massive generation of waste [13,14]. Specifically, with regard to fashion consumption, in their research with young consumers in the UK, ref. [5] identified that they were unaware of the environmental, ethical, and social problems caused by the consumption of fast fashion. In addition, they had a low propensity to use second-hand clothing and objects. This is in line with [15], who found that the majority of 10th grade students admitted having more clothes than they needed and that they mostly bought them in franchises considered to be ‘fast fashion’. However, very few were aware of the origin of the clothes they bought, and even fewer reflected on the need for more information. With respect to their responsibility as consumers for the problems generated by ‘fast fashion’, about half of them took little or no responsibility at an individual level; rather, they pointed the finger at companies or governments for failing to put more controls in place.

According to [16], these unsustainable patterns of consumption and resource use represent an obstacle to achieving a sustainable future. Therefore, these authors insisted on the need for changes in cultural practises to reduce consumption. Hence, it is a matter of increasing the individual responsibility that young people assume in the face of these problems and promoting more sustainable decisions and behaviours [17].

2.2. Education for Sustainability and Key Competencies in Sustainability

EfS should enable students to reflect on their own actions, considering their current and future impacts and taking into account the local and global scales [18]. Furthermore, it is expected to enable students to analyse and solve sustainability problems, as well as to create and take advantage of opportunities aimed at promoting social and environmental justice [19].

Socio-environmental problems and challenges have specific characteristics, so analysing them and trying to find sustainable solutions require teaching that goes beyond conceptual literacy and even awareness-raising. Cognitive, emotional, and behavioural skills [20] must be fostered in order to build a citizenry that is competent to face these challenges [11].

Key competencies in sustainability are a fundamental reference point for developing this ambitious profile of knowledge and skills among students so that they can act as “agents of change” [21]. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that the concept of competence in the field of education initially emerged from an economic perspective, which may be controversial when used in the framework of education for sustainability. Assuming this, this paper builds on [21]’s view of competences. These authors defined competence as “a functionally linked complex of knowledge, skills, and attitudes that enable successful task performance and problem solving with respect to real-world sustainability problems, challenges, and opportunities” [21] (p. 204).

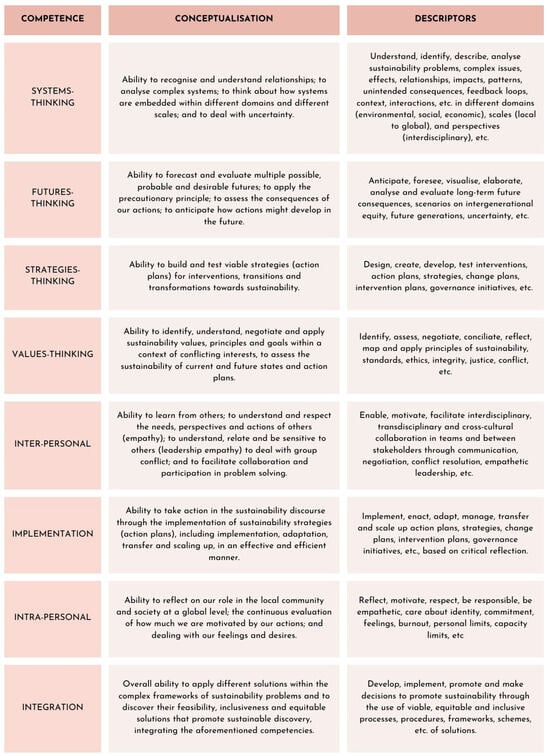

Numerous authors have recognised the importance of these key competencies for advancement on the path to sustainability and social and environmental justice [22,23,24]. But there is also evidence of excessive theorisation and little operationalisation of these competencies in specific actions [25]. Recently, [26] updated the previous work of [21], redefining these key competencies in sustainability precisely to facilitate their operationalisation. In total, these authors delimit eight key competencies (Figure 1), which are considered indispensable for a critical citizenry that participates in a responsible and informed manner and is capable of advancing social transformations towards sustainability [26].

Figure 1.

Competencies in sustainability. Own elaboration based on [26].

For all these reasons, it is essential to develop competencies aimed at involving students in sustainability from the time they begin to receive their compulsory education. Therefore, the main objective of this paper is to assess the level of acquisition of sustainability competencies by students in different years of Compulsory Secondary Education. Our interest is focused on discussing how this educational stage contributes to the development of these competencies in the classroom.

3. Objectives

The main objective of this work is to carry out an exploratory analysis to assess the level of acquisition of competencies in sustainability of students in different years of Secondary Education. Our interest is focused on discussing how these competencies are developed along Compulsory Secondary Education (7th to 10th grades).

Therefore, the central question that the research aims to address is the following: What is the level of acquisition of competencies in sustainability of secondary school students when they are confronted with a real conflict situation associated with the production and consumption of ‘fast fashion’?

4. Methodology

4.1. Participants

A total of 237 students, 12–17 years old, who were receiving Compulsory Secondary Education, participated in this research (Table 1). All of them attended schools located in rural areas of SE Spain, where agricultural activity dominates, with a medium socio-economic level. The academic performance of students in these schools is similar to that of the region as a whole.

Table 1.

Distribution of students by academic year.

The selection of participants was non-probabilistic and, as the students were minors, participation was conditional on the informed consent of their families or guardians. The data obtained were treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, having received permission from the Ethics Committee on Humans of the University of Murcia (ID2526/2019).

4.2. Tools for Data Collection

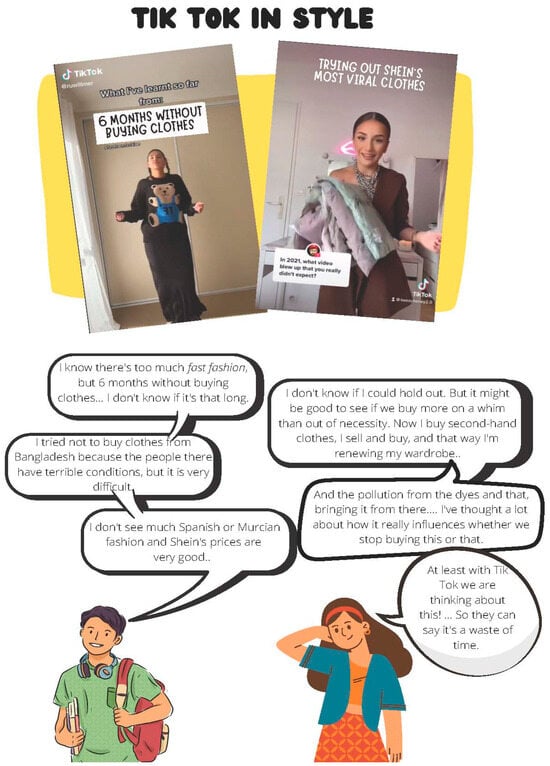

To obtain the students’ responses, the teacher posed a problem based on a fictitious conversation between two young people about two TikTok challenges related to the mass consumption of clothing (Appendix A). This is a scenario in which students can feel involved [27] and, therefore, generate greater reflections in the classroom [28].

Next, a set of seven questions about this problem was presented to the students, whose answers were collected as a personal report. So, it included their assessments of the problems linked to fast fashion, how these affect other people, and their willingness to change clothing consumption habits. The correspondence between the questions appearing in the personal report and the sustainability competencies is shown in Table 2, except for integrated conflict resolution, which results from the integration of the others.

Table 2.

Questions included in the student report and competencies to which they correspond.

These questions were validated using the Delphi method within the framework of a larger project that included the analysis of competencies in sustainability in the face of conflicts linked to consumption. This validation was carried out by a group of experts in Science Education and EfS on the basis of an initial structured questionnaire. Through this method, a consensus was reached on the questions, all of which were open-ended and suitable for assessing each competence (Table 2). In addition, it was agreed that the integrated competence, due to its status, would result from the global computation of the previous ones.

Throughout this process, it was assumed that assessment of the level of competence development on the basis of student responses has its limitations and is exclusively exploratory in nature. Thus, according to [29], this methodology allows an approximation to the initial diagnosis of the competence profile of the students when faced with complex socio-environmental problems. In this way, it is possible to make objective comparisons among grades, as this article aims to do.

4.3. Criteria for Data Analysis

Given that these are open-ended responses, a rubric was developed that allowed the assessment of the competence profile to be operationalised from the students’ responses [30]. Specifically, four levels representing the degree of development of each of the competencies were established (Table 3).

Table 3.

Rubric to assess the competence profile of the students for each competence.

In order to adjust and validate the rubric, we followed [29]’s methodology. Firstly, a preliminary application of the rubric was performed, in our case, on a sample of 15% of the participants. The result of this application was analysed and discussed by the research team (internal validation) to determine its applicability and whether or not it reflected the objectives. Then, the wording of those descriptors that were considered appropriate and necessary was adjusted. The results of the application of this preliminary rubric were validated in a panel discussion of experts in Science Education and EfS, who were asked to evaluate both the general approach of the rubric and each of the categories (“competencies”) and descriptors. The result of this external validation was translated, after modification of some categories and descriptors, into the preliminary rubric 2. The preliminary rubric 2 was then applied, for which one of the authors proposed the assignment of the level achieved by the students for each of the competencies. In order to ensure the reliability of this assignment, a random sample of 25% of the responses—60 for each question—was analysed in a second cycle by another author. The Cohen’s Kappa coefficient obtained for each competence was between 0.68 and 0.77, reflecting “substantial” agreement, according to [31].

For data treatment, descriptive statistics were derived by calculating frequencies for each level in total and separately for each grade. In addition, the mean value was calculated for each competence, where values close to 1 reflect a low competence profile and those close to 4 reflect a high competence profile. In order to assess differences among grades, the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test and its post hoc were applied, with a significance level of p ≤ 0.05.

We are aware that assessing the level of competence development based on the answers to certain questions has its limitations. However, in accordance with [29], it does allow us to approach the initial diagnosis of the competence profile of students when faced with complex socio-environmental problems, which is the aim of this article.

5. Results

The overall results show that, for all competencies, the highest frequencies correspond to the lowest levels (1 or 2). Thus, the mean values indicate that the students, in general, had a low competence profile (Table 4).

Table 4.

Number of students at each level and the average value for each competence.

In order to examine these results more closely, they are described below specifically for each of the eight competencies, including examples of the students’ responses.

5.1. Systems-Thinking Competence

When the students assessed the key aspects of the problems associated with fast fashion, the vast majority of them recognised a single perspective (Table 4). They generally referred to pollution processes in generic terms (Level 1), with statements such as “You pollute the planet when you throw that garment away” (Student 12).

More often, the students recognised these environmental impacts on a global and local scale. For example, one student said, “When we make clothes, we pollute the places where they are made and then, when we bring them here, with the transport and so on, we pollute the atmosphere and produce climate change” (Student 207).

In minor proportions, some of the students also considered socio-economic aspects, such as the overexploitation of workers, but they did not manage to clearly connect these impacts with ecological ones (Level 3). This is the case of Student 51, who stated: “Because it is cheaper and more popular, people buy more, so more has to be produced, causing more pollution in the environment and overexploiting workers where it is produced”. Only three students reached level 4; they established strong relationships among the different dimensions of the problem by reading at different scales and considering uncertainty. For example, they responded: “As dyes and toxic products are used to make clothes, they pollute the rivers there, and, in the end, people can no longer use that water or eat the fish because it is polluted. So, even if they stop making clothes there, that pollution will be difficult to solve, and they are left with the problem” (Student 114).

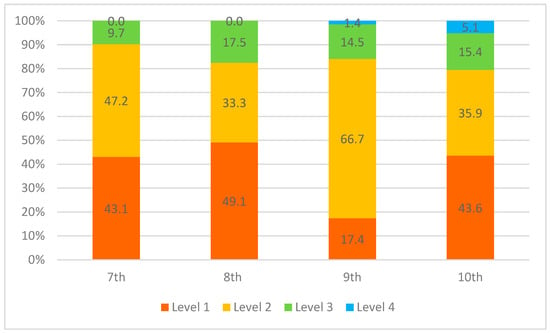

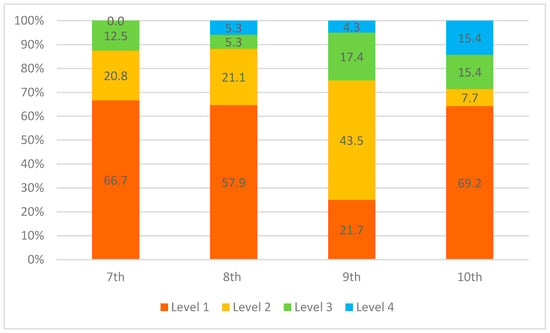

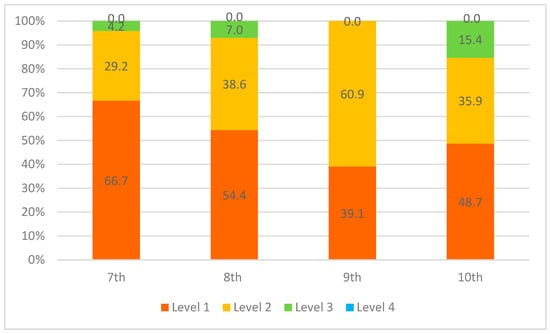

When assessing the differences among grades, it can be seen that levels 1 and 2 dominate in all of them (Figure 2), with higher competence development being very infrequent. No statistically significant differences were found among grades (Z = 4.372; df = 3; p = 0.224).

Figure 2.

Percentage of students at each level of the development of systems-thinking competence for the different grades.

5.2. Futures-Thinking Competence

When the students considered the future of the problem, more than half of them focused on very superficial aspects, without assessing the advantages or risks of different actions, placing them at level 1 (Table 4). This is the case of statements such as “It will stay the same because there are people who like it the way it is” (Student 212) or “It will get worse because fashions like this don’t stop” (Student 41).

One-third of the students were able to envisage possible futures, focusing on a specific action (Level 2), for example, when referring to a consumerist citizenry and away from the impacts of the textile industry. Thus, Student 193 stated, “It will get worse, because we do not see what is behind the brands and we buy more and more every day.

To a lesser extent, the students made more in-depth assessments of the advantages or risks of certain actions (Level 3). For example, Student 226 stated, “It will stay the same, because online shopping will increase. Or it will get worse because companies make money from it and people will not stop shopping until it affects them directly”. No student reached level 4 in this competence.

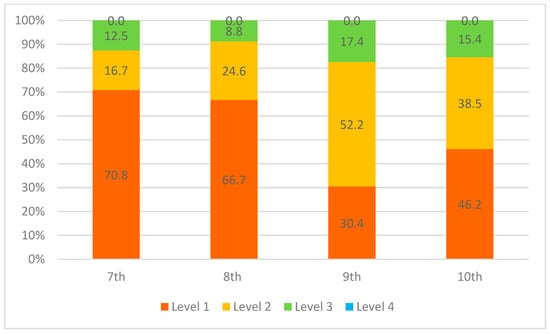

Statistical significance exists in the differences by grade (Z = 9.388; df = 3; p = 0.025). When exploring where these differences reside, the post hoc analysis located them only between the 7th and 9th grades (Z = −2.379; p = 0.017). The data indicate that, although the lower levels dominate in both years, the relative proportions between them suggest that in the 9th grade the level of competence development would be higher (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Percentage of students at each level of the development of futures-thinking competence for the different grades.

5.3. Strategies-Thinking

In general, the students attributed the success of fast fashion to two aspects: social networking and its very cheap price. When assessing the possible alternatives, it can be seen that the vast majority of the students’ responses correspond to levels 1 and 2 (Table 4), as they did not go as far as to consider reducing consumption.

Less than one-fifth are at level 3, recognising the need to reduce clothing production through short-term actions, mainly through second-hand purchases. Finally, six students reached level 4. These were students who proposed, in addition to the buying of second-hand garments, that the reuse of clothes should be encouraged, together with the promotion of local shops and production. Thus, different options that would happen at different time intervals (all three: short, medium, and long-term) are included.

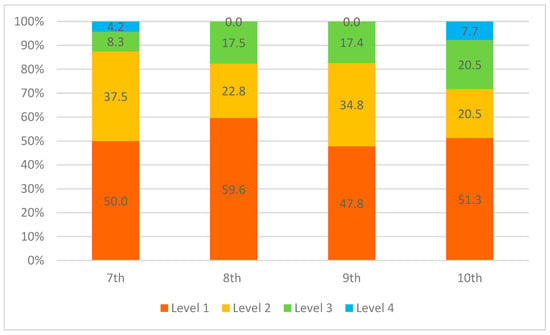

When assessing the competence profile by grade (Figure 4), it can be seen that the relative proportions of higher and lower levels are similar across all the grades, so that no significant differences are detected among grades (Z = 0.661; df = 3; p = 0.882).

Figure 4.

Percentage of students at each level of the development of strategies-thinking competence for the different grades.

5.4. Values-Thinking Competence

When the students reflected on our influence as consumers, most of them failed to identify the consumerist values of our society (Level 1). For example, Student 130 stated, “I could not face up to a company”. This suggests significant difficulties in recognising the role of demand in the issue.

Meanwhile, around a quarter of the students, while identifying these consumerist values, focused on the role of government as the main responsible party (Level 2), with responses such as “Governments would have to do something to control it” (Student 16).

Much more infrequently, some students identified different parties responsible for the problem, including themselves, and even recognised the importance of consensus (Levels 3 and 4, respectively). These students made statements such as, “I know that I also have an influence. I only buy when my clothes don’t fit anymore, but currently manufactured garments are less durable, and fashion sometimes makes you want something new” (Student 211, Level 3); or “Consumers, influencers, clothing brands, and governments need to agree on how to get people to be more sustainable when we buy clothes” (Student 109, Level 4).

The differences according to grade are significant (Z = 8.093; df = 3; p = 0.044). In the post hoc analysis, such differences are found when comparing the 9th grade with the 7th and 8th grades (Z = 2.379; p = 0.009 and Z = −2.164; p = 0.030, respectively). The data suggest that in the 9th grade, the level of acquisition of this competence is higher than in the other two (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Percentage of students at each level of the development of values-thinking competence for the different grades.

5.5. Inter-Personal Competence

When analysing the students’ degree of empathy, it is observed that the highest average value among the different competencies is obtained, being the only one greater than 2 (Table 4). Some of the students referred to the different socio-cultural realities of fast fashion producing countries without considering situations of social injustice (Level 1). For example, they indicated, “In these countries, people have it quite difficult” (Student 73).

The majority of the students, however, did consider this social injustice, even if only in a general way (Level 2), indicating the overexploitation of workers in these countries. Almost one-quarter of the participants referred to such overexploitation and were even more specific in their response (Level 3), with statements such as: “These people work all day long for a miserable salary, in basements and crowded together, they have no rest and, on top of that, many of them may be children; it’s super unfair” (Student 24).

Rather less frequently, some of the students compared the situations in fast fashion producing and consuming countries, noting: “In our country we have more job guarantees and more educational opportunities than in the countries where the clothes are made. In the end we buy cheaply at the expense of exploiting people, even children, from other parts of the world. We would not accept to live like that” (Student 97, Level 4).

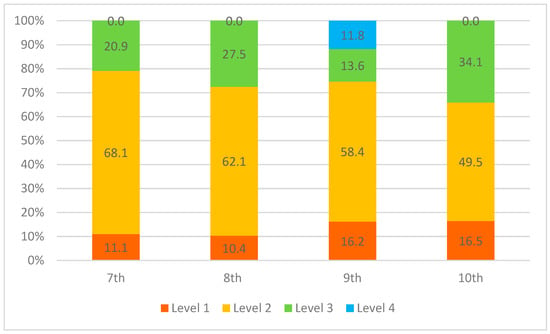

When analysing the levels by grade (Figure 6), no significant differences are seen (Z = 2.053; df = 3; p = 0.561), so it seems that this competence has an equivalent level of development in all of them.

Figure 6.

Percentage of students at each level of the development of inter-personal competence for the different grades.

5.6. Implementation Competence

When the students reflected on the sustainability of youth clothing consumption, the level of self-criticism was low. Most of them did not question their own practises and did not propose changes in their decisions in this respect, this being one of the competencies with the lowest average values (Table 4).

The students tended to make generic considerations, far from a critical reading of youth fashion consumption (Level 1), or used very banal arguments (Level 2). In these cases, they gave answers such as “People want to look fashionable” (Student 207, Level 1) or “Young people like to be trendy and we should think twice before buying something new” (Student 23, Level 2).

More specifically, less than 10% of the students recognised that their motivations are driven more by price than by sustainability (Level 3) and recognised the need to act, stating: “We could do clothes swaps between friends or even at school to buy less, because it is true that we are very fashion-driven” (Student 128). Only two students were able to question their own consumption practises as young people and proposed actions related to the reduction in clothing consumption, even being willing to pay more for brands that guarantee decent conditions for workers.

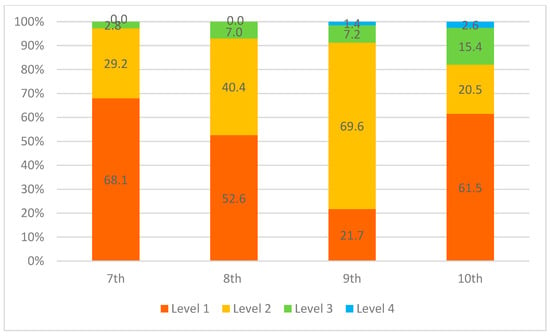

In relation to the different grades (Figure 7), no significant differences were found among them (Z = 1.433; df = 3; p = 0.698). Therefore, the difficulty of critically questioning their fashion consumption practise seems to be common.

Figure 7.

Percentage of students at each level of development of implementation competence for the different grades.

5.7. Intra-Personal Competence

In terms of what the students were willing to do about their clothing consumption habits, the frequencies were found to be similar for levels 1 and 2 (Table 4). So, either they were incredulous about the need for these changes (Level 1) or they showed some willingness to change, but without acknowledging that they were part of the problem or feeling affected by it (Level 2). In the latter case, they used statements such as “It is important that each of us do something because it is a problem” (Student 108).

Some students (n = 32) felt that this problem affects them (Level 3), but did not seem to recognise how their habits contribute to the problem´s generation or solution. For example, Student 72 stated: “This ends up affecting all of us, so I would put it on the internet to make young people see and think where the clothes come from” (Figure 7). No student reached level 4.

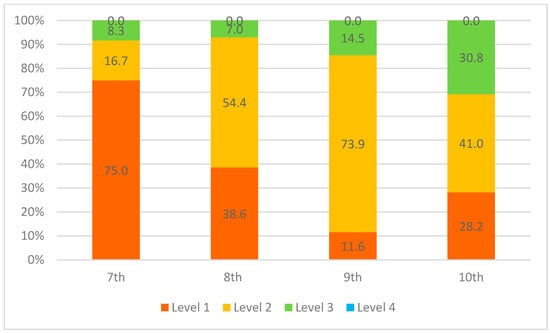

When considering the different grades, we find a clear dominance of level 1 in the 7th grade, as well as of level 2 in the 8th and 9th grades (Figure 8). In the 10th grade, although level 2 dominates, there is an increase in the frequency of level 3. These differences are significant (Z = 17.102; df = 3; p < 0.001). The subsequent analysis indicates that the 7th grade shows a different trend to the others (1st–2nd grades: Z = −2.051; p < 0.040; 1st–3rd: Z = −3.758; p < 0.001; 1st–4th: Z = −2.185; p < 0.029), with a lower level of acquisition of this competence.

Figure 8.

Percentage of students at each level of the development of intra-personal competence for the different grades.

5.8. Integration Competence

Inasmuch as this competence is a joint reflection of the others, its average value shows the limited competence level prevailing among the students (Table 4). Only 5% of the students reached level 3.

The differences according to the grade are not significant (Z = 2.004; df = 3; p = 0.572). Therefore, this competence was poorly developed in all grades (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Percentage of students at each level of the development of integration competence for the different grades.

6. Discussion and Educational Implications

This work is an exploratory study, that is, a first insight into the development of sustainability competencies among secondary school students. Given the number of participants and the collection instrument, the data should be treated with caution and cannot be extrapolated directly. The results obtained with the proposed instrument should be combined with those achieved using other instruments in order to carry out a triangulation process that provides more complete conclusions. Nevertheless, this work reveals trends that are interesting to assess, especially in terms of what happens to this competence profile throughout Secondary Education. So, it might be considered as a starting point for more in-depth comparative studies.

The overall results reflect a predominance of lower levels of development in all competencies and in all grades. This shows that these students still needed to improve in the acquisition of these competencies, in line with other studies [32].

The competence with the most advanced profile was the interpersonal competence. The students easily recognised that people in garment-producing countries suffer from over-exploitative working conditions. Hence, they seemed to be aware of situations of social injustice in other countries resulting from fast fashion. Nevertheless, few of them were able to make an explicit link between these injustices and our own privileges. For their part, the student linked the economic dimension of the problem very closely to the causes of the problem when they recognised that the low price of this clothing drives its consumption [33].

The fact that they contemplated these social and economic aspects is interesting, insofar as a discourse focused on environmental impacts generally dominates when students assess socio-environmental issues [34,35]. Thus, although they were able to recognise different dimensions, the students’ limitations lay in achieving a complex reading of the problem, interconnecting them, and approaching systems-thinking [36,37]. Failure to build strong relationships between these domains can decouple socio-economic processes, such as population consumption patterns, from ethical and ecological processes [38].

In addition, when assessing alternatives (strategies-thinking competence), less than one-fifth of the students focused on these consumption patterns. This may reflect a certain reluctance to consider the need to reduce clothing purchases [5,15]. Moreover, this reluctance seems consistent with the students’ responses when reflecting on fashion consumption, as they did not attend to the prevailing consumerist values in our society (values-thinking competence), nor did they question their own practises (implementation competence) or how they contribute to the problem (intra-personal competence). All this highlights the strong synergy among the competencies and, in this particular context, leads us to ask whether these difficulties are related to a view of consumerism as a practise intrinsic to our society. In this way, the need to discuss the situation is not even recognised, or it may even be justified by linking consumerism to the idea of development [14].

So, although the students easily acknowledged certain environmental impacts of fast fashion and were aware of the overexploitation of others involved, they did not really show a willingness to accept major changes in their clothing consumption. Barriers to the adoption of change, especially when it implies more effortful actions, are widely recognised in the literature [39,40]. They were even assumed by the students themselves, who, even with poorly elaborated arguments, agreed that the problem is unlikely to improve as consumption patterns are unlikely to change (futures-thinking competence).

Considering the results of the different competencies as a whole and given that the integration competence integrates all the previous ones, it seems reasonable to accept that these students would find it difficult to make decisions in the complex framework of sustainability.

However, it is interesting to assess the differences detected among grades, where five out of the eight competencies show similar levels of development with age. When delving deeper into those with significant differences, the results suggest that there is greater success in those competencies linked to the emotional domain [17,41]. The students in higher grades, even with the aforementioned difficulties, seemed to be more competent in feeling part of the problem of fast fashion and assuming the consumerism of our society. Additionally, they showed a greater ability to assess the advantages and risks of different actions. Nevertheless, even with these improvements, it seems possible to affirm that, according to our results, Secondary Education is not actively contributing to the development of competencies in sustainability [32]. The acquisition of these competencies does not happen implicitly when dealing with the contents or basic knowledge of the different subjects [18,42]. The implementation of transformative pedagogical strategies with a deeper reflection on the ethics of fashion in terms of the ethics of consumption is necessary [17]; as is a revision of the contents that are hosted in the current curricula.

In this regard, an overall reading of the results of this work indicates that developing a competence profile in sustainability involves overcoming three major difficulties in the teaching and learning process, which have been widely pointed out in educational research:

- Firstly, it is difficult for students to analyse and evaluate complex systems and to develop strategies and action plans to address the underlying problems [43]. For [44], addressing systems-thinking from practical experiences for the development of action plans also favours the development of futures-thinking competence among students, with greater management of uncertainty and assessment of the impact of different decisions. This again highlights the strong synergy among the different competencies.

- Also, it is difficult for students to become emotionally and affectively involved in the problems and to act accordingly [24]. According to our work, as they progress through Secondary Education, they seem to show greater ability to identify consumerist values and to feel affected by the resulting issues. However, this awareness does not translate into a greater willingness to change their habits [45]. Thus, the maintenance of unsustainable consumption patterns continues to be one of the greatest obstacles to achieving sustainability [16].

- Finally, another major difficulty lies in the implementation of educational practises aimed at helping students overcome the above obstacles [46,47]. Different studies indicate that teachers do not always recognise themselves as agents of change, nor are they confident in their ability to integrate EfS in their classrooms [45,48], perhaps related to the available time limitation, bureaucratic pressures and legislation, and/or the lack of emphasis during their initial training. Added to this is the challenge for teachers to evaluate their students in terms of changes and achievements in sustainability [49,50].

In the face of these major difficulties, [19] pointed out that the commitment of teachers is fundamental in its twofold dimension: in a personal dimension, to tackle socio-environmental problems; and, in a professional dimension, to actively involve students in them. This commitment is related to their teaching capacities to create meaningful learning environments [23]. Therefore, a priority area for action to develop transformative pedagogical strategies in classrooms is to enhance teachers’ competencies [17,51]. These, according to [52], are the most important bottlenecks in the promotion of school-based sustainability. Furthermore, developing teachers’ competencies to practise sustainability education will, in turn, foster competencies among their students, advancing the empowerment of citizens to face the environmental and social justice challenges of this century [22].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.B.-G. and P.E.-G.; methodology, I.B.-G., P.E.-G. and A.R.-N.; analysis, M.Á.G.-F. and M.V.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, I.B.-G. and P.E.-G.; writing—review and editing, A.R.-N., M.Á.G.-F. and M.V.-P.; supervision, I.B.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by the MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 under Grant PID2019-105705RA-I00.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee) of University of Murcia (protocol code 2526/2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Statement of the activity.

References

- Prata, J.C.; da Costa, J.P.; Lopes, I.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. Environmental exposure to microplastics: An overview on possible human health effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 702, 134455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Sun, P.; Lin, B.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Ma, R.; Xiang, M.; Li, H.; Guo, S. Effects of ambient air pollution from municipal solid waste landfill on children’s non-specific immunity and respiratory health. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 236, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirvanimoghaddam, K.; Motamed, B.; Ramakrishna, S.; Naebe, M. Death by waste: Fashion and textile circular economy case. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 718, 137317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The environmental price of fast fashion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, L.R.; Birtwistle, G. An investigation of young fashion consumers’ disposal habits. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P.; Abbate, S.; Nadeem, S.P.; Garza-Reyes, J.A. Slowing the fast fashion industry: An all-round perspective. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 38, 100684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.; Li, M.; Lenzen, M. The need to decelerate fast fashion in a hot climate-A global sustainability perspective on the garment industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future. 2017. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/a-new-textiles-economy (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Bick, R.; Halsey, E.; Ekenga, C.C. The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. Environ. Health 2018, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kant, R. Textile dyeing industry: An environmental hazard. Nat. Sci. 2012, 4, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán-Arcos, S.; Pérez Martín, J.M.; Esquivel-Martin, T. Educación para la justicia ambiental: ¿Qué propuestas se están Realizando? RIEJS 2022, 11, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann, M.; Barth, M. Educators’ Competence Frameworks in Education for Sustainable Development. In Competences in Education for Sustainable Development. Critical Perspectives; Vare, P., Lausselet, N., Rieckmann, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 19–26. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-91055-6_3 (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Fernández Manzanal, R.; Hueto Pérez de Heredia, A.; Rodríguez Barreiro, L.; Marcén Albero, C. ¿Qué miden las escalas de actitudes? Análisis de un ejemplo para conocer la actitud hacia los residuos urbanos. Ecosistemas 2003, 11, 11–27. Available online: https://www.revistaecosistemas.net/index.php/ecosistemas/article/view/347 (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Marcén, C.; Fernández Manzanal, R.; Hueto, A. ¿Se pueden modificar algunas actitudes de los adolescentes frente a las basuras? Investig. En La Esc. 2002, 46, 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Banos-González, I.; Esteve, P.; Jaén, M.; Fortes, M.A. Secondary school students facing fashion consumption and disposal. In Proceedings of the 13th Conference of European Researchers in Didactics of Biology ERIDOB 2022, Nicosia, Cyprus, 29 August–2 September 2022; Available online: https://2022.eridob.org/images/pdfs/abstracts.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Goldman, D.; Alkaher, I.; Aram, I. “Looking garbage in the eyes”: From recycling to reducing consumerism- transformative environmental education at a waste treatment facility. J. Environ. Educ. 2021, 52, 398–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Education for the Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000252423?locale=es (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Rieckmann, M. Learning to transform the world: Key competencies in Education for Sustainable Development. In Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development; Leicht, A., Heiss, J., Byun, W.J., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018; pp. 39–59. [Google Scholar]

- González Reyes, L.; Gómez Chuliá, C. La competencia ecosocial en un contexto de crisis multidimensional. RIEJS 2022, 11, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinakou, E.; Donche, V.; Van Petegem, P. Teachers’ profiles in education for sustainable development: Interests, instructional beliefs, and instructional practices. Environ. Educ. Res. 2024, 30, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M. Implementing Sustainability in Higher Education: Learning in an Age of Transformation; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Timm, J.M.; Barth, M. Making education for sustainable development happen in elementary schools: The role of teachers. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 27, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E.J.; Lenglet, F. Sustainability citizens: Collaborative and disruptive social learning. In Sustainability Citizenship in Cities: Theory and Practice; Horne, R., Fien, J., Beza, B., Nelson, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Waltner, E.M.; Riess, W.; Mischo, C. Development and Validation of an Instrument for Measuring Students’ Sustainability Competence. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, A.; Wiek, A. Competencies for Advancing Transformations Towards Sustainability. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 785163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila Cutiño, Y.; Díaz Castillo, R.; Espinosa Cruz, L. La educación para el consumo sostenible de adolescentes y jóvenes. Didáctica Y Educ. 2020, 11, 42–51. Available online: https://revistas.ult.edu.cu/index.php/didascalia/article/view/1101 (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Román, R. Competencias de Sostenibilidad y Enfoques Pedagógicos para la Educación. Observatorio. Instituto para el Futuro de la Educación. 2021. Available online: https://observatorio.tec.mx/edu-news/competencias-de-sostenibilidad-y-enfoques-pedagogicos-educacion/ (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- García, M.R.; Junyent, M.; Fonolleda, M. How to assess professional competencies in Education for Sustainability? An approach from a perspective of complexity. Int. J. Sustain. Higher Ed. 2017, 18, 772–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, P.; Papanikolaou, A. Examining Pre-Service Teachers’ Critical Thinking Competences within the Framework of Education for Sustainable Development: A Qualitative Analysis. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. An application of hierarchical kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics 1977, 33, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Aboytes, J.G.; Nieto-Caraveo, L.M. Assessment of Competencies for Sustainability in Secondary Education in Mexico. In Sustainable Development Research and Practice in Mexico and Selected Latin American Countries, World Sustainability Series; Leal Filho, W., Noyola-Cherpitel, R., Medellín-Milán, P., Ruiz Vargas, V., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Sojo, M.C.; Krych, K.; Pettersen, J.B. Evaluating the current Norwegian clothing system and a circular alternative. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 197, 107109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteve-Guirao, P.; Banos-González, I.; García, M. The Interdependences between Sustainability and Their Lifestyle That Pre-Service Teachers Establish When Addressing Socio-Ecological Problems. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramm, J.; Steinhoff, S.; Werschmöller, S.; Völker, B.; Völker, C. Explaining risk perception of microplastic: Results from a representative survey in Germany. Global Environ. Chang. 2022, 73, 102485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdsall, S. Measuring student teachers’ understandings and self-awareness of sustainability. Environ. Educ. Res. 2014, 20, 814–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourn, D.; Kalsoom, Q.; Soysal, N.; Ince, B. Student Teachers’ Understanding and Engagement with Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in England, Türkiye (Turkey) and Pakistan; Development Education Research Centre Research Paper no. 23; UCL Institute of Education: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Valderrama-Hernández, R.; Alcántara Rubio, L.; Sánchez-Carracedo, F.; Caballero, D.; Serrate, S.; Gil-Doménech, D.; Vidal-Raméntol, S.; Miñano, R. ¿Forma en sostenibilidad el sistema universitario español? Visión del alumnado de cuatro universidades. Educación XXI 2020, 23, 221–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, G.T.; Stern, P.C. Environmental Problems and Human Behavior, 2nd ed.; Pearson Custom Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmi, N.; Arnon, S.; Orion, N. Transforming environmental knowledge into behavior: The mediating role of environmental emotions. J. Environ. Educ. 2015, 46, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinert, F.E. Concept of competence: A conceptual clarification. In Defining and Selecting Key Competencies; Rychen, D.S., Salganik, L.H., Eds.; Hogrefe & Huber Publishers: Göttingen, Germany, 2001; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, A.; Lehmann, S. The zero waste index: A performance measurement tool for waste management systems in a ‘zero waste city’. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza Rios, M.M.; Herremans, I.M.; Wallace, J.E.; Althouse, N.; Lansdale, D.; Preusser, M. Strengthening sustainability leadership competencies through university internships. Int. J. Sustain. Higher Ed. 2018, 19, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Borreguero, G.; Maestre-Jiménez, J.; Mateos-Núñez, M.; Naranjo-Correa, F.L. Analysis of Environmental Awareness, Emotions and Level of Self-Efficacy of Teachers in Training within the Framework of Waste for the Achievement of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, T.; Roofe, C.; Cook, L.D. Teachers’ perspectives on sustainable development: The implications for education for sustainable development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 1343–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaén, M.; Esteve, P.; Banos-González, I. Los futuros maestros ante el problema de la contaminación de los mares por plásticos y el consumo. REurEDC 2019, 16, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, T. Prepared to Teach for Sustainable Development? Student Teachers’ Beliefs in Their Ability to Teach for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shephard, K. Higher education for sustainability: Seeking affective learning outcomes. Int. J. Sustain. Higher Ed. 2008, 9, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, L. Universities, hard and soft sciences: All key pillars of global sustainability. In Global Sustainability and the Responsibilities of Universities; Weber, L.E., Duderstadt, J.J., Eds.; Economica: London, UK, 2012; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, C.; Mallon, B.; Smith, G.; Kelly, O.; Pitsia, V.; Martínez Sainz, G. The influence of a teachers’ professional development programme on primary school pupils’ understanding of and attitudes towards sustainability. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 1011–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vare, P.; Arro, G.; de Hamer, A.; Del Gobbo, G.; de Vries, G.; Farioli, F.; Kadji-Beltran, C.; Kangur, M.; Mayer, M.; Millican, R.; et al. Devising a Competence-Based Training Program for Educators of Sustainable Development: Lessons Learned. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).