Abstract

In the contemporary university environment, there is a growing trend towards the use of innovative pedagogical methods aimed at increasing student engagement and learner-centeredness. Despite this shift, traditional lecture formats continue to be used, particularly in large classes or language courses. This is largely due to the perceived efficiency and convenience of the traditional lecture format for both teachers and students. However, the limited interaction and communication inherent in traditional lectures can hinder student satisfaction and participation. To address this, the integration of an instant response system (IRS) into the classroom environment offers a promising solution. These systems, which leverage technology and anonymity, facilitate real-time feedback and active student participation without placing a significant burden on the instructor. This study examines the implementation of IRSs in Hindi language learning courses at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Seoul, focusing on their impact on student satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy at different levels of academic achievement. The findings reveal nuanced differences in perceptions and outcomes between high, average, and low achievers, highlighting the potential of IRSs to foster engagement and communication in diverse learner cohorts. Contrary to expectations, satisfaction levels did not consistently correlate with academic performance. In fact, middle achievers showed significant benefits. Qualitative findings further elucidate students’ experiences and highlight the importance of tailored approaches to maximize the effectiveness of IRSs. Overall, this research highlights the adaptability and effectiveness of IRSs in promoting active learning environments, and offers valuable implications for instructional design and pedagogical practice.

1. Introduction

A number of universities are currently trialing a variety of pedagogical approaches, including flipped learning [1,2], problem-based learning, and collaborative teaching, with the aim of enhancing students’ skills and providing learner-centered education. Nevertheless, despite these efforts, university courses continue to rely on the traditional lecture method of teaching. This is particularly evident in large lectures with a high number of students or language courses [3]. In these settings, traditional lectures are often preferred due to their perceived efficacy for efficient learning, which is influenced by a number of factors, including the subject matter, the size of the student population, and the educational environment [4]. However, the preference for traditional lectures may be influenced by the lecturers’ unilateral comfort or negative perceptions of new teaching methods [5,6]. Teachers may prefer traditional lectures due to their convenience, as methods such as flipped learning or problem-based learning (PBL) require significant preparation, including tasks such as video production and team management [6,7].

Nevertheless, traditional classroom management may result in diminished levels of student participation and satisfaction due to constrained communication and interaction between learners or between teachers and learners. Consequently, it is imperative to implement teaching methods that facilitate active interaction in large lectures or language classes, even in the absence of the extensive time and effort typically required for methods such as flipped learning.

The integration of various media and technologies into teaching and learning processes in the education sector has been facilitated by the proliferation of information and communication technologies and the widespread use of smart devices [8]. In order to improve the efficiency of education and create a learner-centered curriculum, numerous initiatives and research efforts are underway to encourage interaction between teachers and students. As part of ongoing efforts, there is a growing trend towards using instant response systems in the classroom. These systems capture student responses in real time, provide timely feedback, and encourage open expression by ensuring anonymity. Furthermore, in an educational setting where smartphones and the internet are prevalent, the instant response system offers the advantage of not requiring significant time or effort for teachers to prepare classes, and it is easily accessible to anyone. In order to align with contemporary trends and environments, it is essential to implement a classroom response system in language courses at the university.

2. Literature Review and Research Focus

A review of research on Korean college students’ perceptions of quality classes [9,10,11] reveals that such classes typically embody characteristics that foster learning motivation, student engagement, frequent instructor feedback, tailored instruction, fair evaluation, professorial expertise, and positive instructor–student relationships. These classes can be further categorized according to the following criteria: teacher passion, effective communication, diverse teaching methods, and the facilitation of student interaction and discussion. It is noteworthy that researchers frequently identify classes where instructors are adept at explaining content, promptly providing feedback, and leading engaging classes [12].

Consequently, an efficacious pedagogical approach to facilitate active communication, stimulate participation, and infuse classes with a sense of enjoyment, while concomitantly reducing the instructor’s workload, is the instant response system (IRS). Previous studies on the IRS or classroom response system (CRS) have primarily assessed satisfaction, learning outcomes, motivation, and participation. These studies have frequently demonstrated favorable perceptions of class quality and academic effectiveness [13,14,15]. Comparisons with traditional classes frequently indicate superior academic performance and knowledge retention among IRS participants [16,17], although some studies report no significant difference [18]. Nevertheless, the IRS facilitates learner-centered approaches and the efficient use of lecture time, fostering self-reflection and collaboration [19,20,21]. The advent of modern technology has made the IRS more accessible through mobile devices, rendering it an effective and convenient teaching tool. It enhances interaction, participation, satisfaction, and academic achievement [22,23].

In contrast to flipped learning and PBL, IRS-based classes prioritize learner engagement and communication, without imposing significant burdens on instructors. However, previous research has frequently failed to consider the potential for differences in learner satisfaction and effectiveness to vary according to variables such as academic achievement results or grades. Consequently, the objective of this study is to examine the disparities in IRS perceptions across different academic achievement levels and to assess the variations in satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy among different grade groups.

In contrast to traditional question-and-answer methods, the IRS provides a distinctive feedback mechanism in educational settings [24]. Conventional methodologies frequently result in passive participation and exclusion among students [25], whereas IRF (Initiation–Response–Feedback) actively engages all students, providing immediate feedback through anonymous quizzes and promoting collaborative learning [26,27]. In IRS environments, students are expected to assume a more active role in their learning, which may influence their participation and motivation based on their grades. This study poses research questions and hypotheses to investigate the effects of IRS-based classes at university.

- How does the IRS’s implementation in university language classes impact student satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy across different achievement levels? It is hypothesized that the IRS will increase satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy, with high achievers reporting the highest levels.

- Do students with lower grades have greater satisfaction with and participation in the IRS? It is hypothesized that lower-grade students will have higher satisfaction and participation in IRS activities compared to higher-grade students.

- What are the perceptions of students regarding the IRS based on their academic performance, as explored through qualitative interviews? It can be reasonably assumed that students’ perceptions of the IRS will vary based on their academic performance.

3. Research Context and Instrument

In recent times, mobile-based classroom response systems have been employed in a variety of educational settings, including those at the vanguard of the educational landscape. Illustrative examples include PingPong and Socrative. Socrative provides both a teacher app and a student app, enabling educators to create up to five quizzes in the form of multiple choice, true/false, and short answer at no cost. Subsequently, teachers can pose questions to students. In essence, any instructor proficient in keyboarding can readily access the program, create questions or problems, have students solve them immediately, share the results with students, and provide feedback.

In Hindi classes at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Seoul, we introduced the instant feedback approach using Socrative and encouraged students to discuss quizzes with their peers. The Elementary Hindi I and Intermediate Hindi I courses are 16-week courses with two-hour weekly sessions. The number of students enrolled in these courses is 38 and 27, respectively. The objective of the courses is to impart knowledge of the grammar and sentence structure of the Hindi language, with a view to facilitating communication and composition at each level. It is recommended that students engage actively in the learning process in order to create an engaging learning experience.

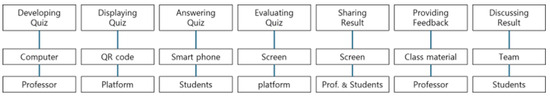

This study aimed to foster student engagement and active participation in the classroom, as well as to assess their understanding of the material. This approach enhanced the learning experience by encouraging enquiry, fostering discussions, and enabling a more profound exploration of the subject matter (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Instant Response System (IRS)-based Hindi classes’ flow.

The study aimed to investigate the potential variation in student motivation in relation to their academic performance. The students were divided into three groups based on their academic performance. Group A comprised students who had achieved an ‘excellent’ or ‘very good’ grade, Group B included students who had received a ‘good’ or ‘not bad’ grade, and Group C consisted of students who had been awarded a ‘bad’ or ‘fail’ grade (see Table 1). The academic scores were determined through evaluations conducted at the conclusion of the semester. Furthermore, academic achievement was evaluated through tests conducted at both the mid-term and the end of the final term.

Table 1.

Participant demographics.

The surveys (See Appendix A) were administered via the university’s Teaching Management System (TMS). The data were analyzed using the statistical software package SPSS 21 in order to investigate students’ perceptions of the IRS. The analysis included an examination of learners’ perceptions of satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy in correlation with their academic performance. The survey results, interpretations, and conclusions are presented in a clear and objective manner.

The results obtained from the SPSS software are derived from Welch’s independent samples t-tests, which assess the equality of means for different variables. The Welch’s tests indicate that all three variables exhibit statistically significant differences in means between the groups under study. This suggests that meaningful distinctions exist in the aspects under investigation (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Robust tests of equality of means.

4. Research Results and Discussion

This study not only presents the means and standard deviations of satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy based on academic performance scores, but also delves deeper into the implications of these findings. It is of paramount importance to comprehend the influence of academic performance on student perceptions if one is to design effective teaching strategies and foster a supportive learning environment.

To comprehensively analyze the relationship between academic performance and student satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy in Hindi classrooms, the study employed a one-way ANOVA. The statistical analysis permitted a detailed examination of the differences between the three distinct academic performance groups: High Achievers (Group A), Average Achievers (Group B), and Low Achievers (Group C). The results of the ANOVA demonstrated significant differences among the three groups for satisfaction (F(2, 62) = 6.379, p = 0.003), engagement (F(2, 62) = 3.979, p = 0.024), and self-efficacy (F(2, 62) = 5.241, p = 0.008).

These findings emphasize the necessity of considering individual academic performance levels when evaluating student experiences and perceptions in the classroom. It is possible that high achievers may have different needs and preferences compared to average or low achievers. Consequently, it is necessary to adopt a tailored approach in order to enhance satisfaction, engagement and self-efficacy across the board. Moreover, the identification of significant differences among these groups highlights the potential benefits of targeted interventions and support mechanisms to address specific challenges faced by students with varying levels of academic performance.

Furthermore, the study provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of teaching methods and classroom practices in promoting positive student outcomes. By examining the relationship between academic performance and student perceptions, educators can gain a deeper understanding of the factors influencing student satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy. This understanding can then inform the development of evidence-based instructional strategies and educational interventions. This comprehensive approach to student assessment and support contributes to the ongoing efforts to enhance the quality and effectiveness of language education in university settings.

4.1. Quantitative Findings

In order to identify significant differences among groups for each variable, namely satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy, multiple comparison tests were employed, including Scheffe, LSD, and Games–Howell as shown in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Analysis: overall results of S-E-S by academic achievement results.

Table 4.

Analysis of the result.

Subsequent analyses were conducted utilizing Scheffé’s and Games–Howell tests with the objective of delving deeper into the differences among the groups concerning satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy. The findings from these analyses provide insight into the subtle variations in student experiences and perceptions within the context of Hindi classrooms.

With regard to satisfaction, both Group A and Group B demonstrated significant differences in comparison to Group C (p = 0.171) and Group E (p = 0.000). The mean differences (M.D.) for A vs. C and B vs. A were 0.5000 (p = 0.171) and 0.8359 (p = 0.000), respectively, indicating notably higher satisfaction levels among Groups A and B in contrast to Groups C and A.

Moving to engagement, Group A demonstrated significantly higher levels compared to Groups C and E, with mean difference (M.D.) values of 0.2968 (p = 0.227) and 0.6470 (p = 0.007), respectively. Furthermore, a significant difference was observed between Group B and Group E (M.D. = −0.6470, p = 0.007), suggesting distinct engagement levels.

With regard to self-efficacy, Group B exhibited significant differences with Groups C (M.D. = 0.4802, p = 0.044) and A (M.D. = 0.7675, p = 0.003). Notably, a significant difference was observed between Group A and Group B (M.D. = −0.7675, p = 0.003). Nevertheless, no significant difference was observed between Groups C and A (p = 0.266).

The post hoc analyses revealed significant differences in satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy between specific pairs of groups, providing valuable insights into the nuanced variations across the study groups. These findings emphasize the necessity of considering individual differences and academic performance levels when designing instructional strategies and support mechanisms with the aim of enhancing student experiences and outcomes in language classrooms. Furthermore, these findings emphasize the necessity for the implementation of targeted interventions to address the diverse needs and preferences of students with varying levels of academic achievement.

The primary objective of this study was to examine the variations in students’ perceptions of the IRS across different academic achievement levels and to evaluate the levels of satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy among various grade cohorts. In order to facilitate student interaction and provide immediate feedback, the research team employed the use of mobile platforms such as Socrative.

The analysis of the survey data revealed significant differences in satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy among high achievers, average performers, and low achievers. Further investigation through subsequent analyses identified specific pairs of groups with notable differences, offering insights into the nuanced variations across academic performance tiers. These findings demonstrated the potential of the IRS to enhance learner engagement and communication within language learning contexts, emphasizing its adaptability and effectiveness across diverse student demographics.

4.2. Qualitative Insights

This study employed a mixed-methods approach, integrating quantitative survey analysis with qualitative interviews with students across a range of academic performance levels. To ensure gender diversity and to capture a comprehensive range of student experiences, one male and one female student from each academic performance group (low, average, and high performers) were selected for interviews. The validity of this approach is supported by the intention to identify potential differences in how male and female students, as well as students with different academic performances, perceive and interact with the IRS. By including both genders and various performance levels, we aimed to minimize bias and ensure a holistic understanding of the system’s impact. The interviews were semi-structured, allowing students to freely express their views while ensuring that key topics related to the IRS’s use were covered.

The primary objective was to gain a comprehensive understanding of students’ perceptions of the IRS based on their academic achievements.

Students in the lower-performing group expressed appreciation for the immediate feedback provided by the IRS, describing it as enjoyable and beneficial. Nevertheless, they demonstrated a reluctance to share incorrect answers on the screen, even when their responses remained anonymous. In contrast, students with average grades reported enhanced engagement and skill development through their interactions with the IRS. Moreover, they expressed a keen interest in extending this approach to other courses, indicating a positive reception towards the implementation of the IRS.

Conversely, students with higher grades perceived IRS quizzes as insufficiently challenging, which consequently limited their perceived benefit in improving learning outcomes. This perspective indicates a necessity for IRS activities to be adapted to accommodate the varying academic capabilities and preferences of students across different performance levels.

The integration of both quantitative and qualitative methodologies provided valuable insights into the multifaceted nature of students’ experiences with the IRS. The study’s ability to capture diverse perspectives has highlighted the potential benefits and challenges associated with the implementation of the IRS in educational settings. This has informed future instructional strategies and technology integration efforts.

4.3. Discussion

The objective of this study was to examine the perceptions of students with varying academic achievement levels (high, average, and low) regarding the use of the IRS in their Hindi language classes. The utilization of surveys and interviews led to the identification of several key findings.

Firstly, the survey results indicated notable discrepancies in satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy across the three academic achievement groups. In contrast to the hypothesis that high achievers would report the highest levels, average achievers exhibited higher levels of engagement and satisfaction. This indicates that the IRS had the most profound impact on the learning experience of average achievers, aligning with constructivist theories that emphasize active engagement and participation in the learning process.

Secondly, the hypothesis that students with lower grades would exhibit higher levels of satisfaction and participation in IRS activities compared to students in higher grades was not supported by the findings. While low achievers expressed appreciation for the immediate feedback provided by the IRS, they demonstrated discomfort with publicly sharing incorrect answers, which led to a reduction in satisfaction. This finding is consistent with Vygotsky’s social development theory, which emphasizes the importance of creating a supportive and non-threatening learning environment.

Thirdly, the qualitative interviews yielded further insights into the variations in perceptions based on academic performance. Low-achieving students indicated a need for increased anonymity, average achievers reported heightened engagement and skill development, and high achievers found the IRS quizzes insufficiently challenging. These findings are consistent with the principles of differentiated instruction, which advocate for the adaptation of educational tools to accommodate the diverse needs of students.

This study challenges previous research by demonstrating significant variability in the effectiveness and satisfaction with educational technology tools such as an IRS across different student groups. While the IRS had a positive impact on average achievers, it is necessary to make adjustments to ensure anonymity for low achievers and to provide more challenging content for high achievers. These findings underscore the importance of customizing educational technology based on individual student characteristics and achievement levels, in contrast with prior studies that did not account for these differences.

5. Conclusions and Research Limitations

The research examined the effectiveness of an instant response system (IRS) in Hindi language courses at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Seoul. The system’s departure from new methods such as flipped learning and PBL is highlighted by its focus on learner engagement and communication, without placing undue burden on instructors. The study aimed to ascertain whether there were any variations in perceptions of the IRS across different academic achievement levels, and to evaluate the levels of satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy among students in different grade cohorts. The research made use of mobile-based platforms such as Socrative to foster student interaction and prompt feedback. Findings from surveys conducted via the university’s TMS and analysed using SPSS 21 revealed notable differences in satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy among high achievers, average performers, and low achievers. Subsequent post hoc analyses revealed specific pairs of groups exhibiting significant distinctions in these variables, thereby providing insight into the nuances of variation across varying academic performance tiers. The study demonstrated the potential of the IRS to enhance learner engagement and communication within language learning environments, underscoring its adaptability and efficacy across diverse student demographics.

The study’s hypothesis and research questions were not supported by the findings. Students with lower grades did not exhibit higher scores in IRS satisfaction, class engagement, and self-efficacy compared to those with higher grades. Nevertheless, students in the mid-performance bracket demonstrated noteworthy outcomes across all metrics. Students with higher grades demonstrated interest in the IRS, yet their satisfaction levels did not reach the same heights as those of other groups. It is notable that the group with average grades displayed heightened levels of class participation, interest, satisfaction, and self-efficacy through the use of the IRS, indicating enhanced learning efficacy.

In order to gain further insight into the survey results, interviews were conducted with one male and one female student from each grade group. Students in the low-performing cohort found the IRS enjoyable and beneficial for immediate feedback. However, they expressed discomfort in sharing incorrect answers on the screen, even anonymously. Conversely, students with average grades noted increased class engagement and skill enhancement through the IRS, expressing a desire for its application in other courses beyond language studies. However, students with higher grades perceived the IRS quizzes and questions to be insufficiently challenging, limiting their perceived benefit in improving learning outcomes.

Consequently, the study employed both quantitative survey analysis and qualitative interviews with students across different grade levels to ascertain their perceptions of the IRS based on their academic performance. This approach provided valuable insights into the efficacy of the IRS and its potential for diverse learner groups.

One potential limitation of this study is its narrow focus on a specific language course within a single university context. This may restrict the applicability of the findings to broader language education settings. Moreover, the utilization of self-reported data from surveys and interviews may potentially introduce response bias and subjectivity. To address these limitations, future research could undertake longitudinal studies spanning various language courses and institutions. This would facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of the efficacy of the IRS across diverse contexts. Furthermore, the integration of objective measures of learning outcomes, such as standardized tests or performance assessments, could provide a more robust evaluation of the effectiveness of the IRS. Furthermore, an investigation into the role of instructor training and support in implementing IRS strategies may prove beneficial in enhancing their impact on learner engagement and communication. Finally, it is recommended that cultural factors and learner preferences be considered in the design and execution of IRS activities, in order to facilitate the creation of more tailored and effective language learning experiences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-J.K. and Y.-J.K.; methodology, T.-J.K.; data curation, Y.-J.K.; writing—original draft, T.-J.K.; writing—review and editing, T.-J.K. and Y.-J.K.; funding acquisition, Y.-J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Hankuk University of Foreign Studies: This work was supported by the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies in 2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions. Classes and surveys were conducted with student consent according to the research protocols approved by the university IRB.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the article, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Survey of Instant Response System-Based Class

- S1. I thoroughly enjoyed my involvement in the instant response system (IRS)-based class.

- S2. My interest in learning the foreign language increased through IRS-based classes.

- S3. By participating in the IRS-based class, I found it more interesting than the class without instant feedback.

- S4. I felt that IRS-based language classes were better than traditional general language classes.

- S5. The instructor actively conducted the IRS-based class.

- E1. I comprehended the objectives of the IRS-based class and actively engaged in the activities.

- E2. I was able to identify my lacking capabilities through IRS-based classes.

- E3. I was able to communicate smoothly not only with the instructor but also with other learners in the IRS-based class.

- E4. I strongly believe that IRS-based classes encourage students to participate in class actively and enthusiastically.

- E5. The anonymous nature of the IRS-based class empowered me to actively engage in asking and answering questions.

- S-E1. I learned more in IRS-based classes than in regular language classes.

- S-E2. I believe that IRS-based classes enhance the understanding of course content.

- S-E3. I was able to overcome my weak areas through IRS-based classes.

- S-E4. IRS-based classes helped me understand the views and levels of other learners.

- S-E5. I believe that IRS-based teaching is an effective teaching method in language classes as well.

References

- Zheng, L.; Bhagat, K.; Zhen, Y.; Zhang, X. The Effectiveness of the Flipped Classroom on Students’ Learning Achievement and Learning Motivation: A Meta-Analysis. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2020, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, T. A case study of PBL application in the online classes of Indian languages. Stud. Foreign Lang. Educ. 2022, 36, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostka, I.; Lockwood, R. What’s on the Internet for flipping English language instruction? Electron. J. Engl. A Second. Lang. 2015, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, H. The integration of a student response system in flipped classrooms. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2017, 21, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Strayer, J.F. How learning in an inverted classroom influences cooperation, innovation and task orientation. Learn. Environ. Res. 2012, 15, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.W.; Shen, P.D.; Lu, Y.J. The effects of problem-based learning with flipped classroom on elementary students’ computing skills: A case study of the production of ebooks. Int. J. Inf. Commun. Technol. Educ. 2015, 11, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Sands-Meyer, S.; Audran, J. The effectiveness of the student response system (SRS) in English grammar learning in a flipped English as a foreign language (EFL) class. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2019, 27, 1178–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, S.; Khera, O.; Getman, J. The experience of three flipped classrooms in an urban university: An exploration of design principles. Internet High. Educ. 2014, 22, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Kim, H. Defining a “Good Instruction”: The Qualitative Study of Undergraduate Students in Korea. J. Educ. Idea 2008, 22, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M. Students’ Perceptions of Good Teaching in Higher Education—An Essay-Review of College Students. J. Humanit. Stud. 2008, 35, 229–253. [Google Scholar]

- Im, S.; You, Y. A Critical Discourse Analysis on the ‘Quality College Classes’. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 34, 1079–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J. Perception and Effects of Classroom Response System Use. J. Educ. Technol. 2013, 29, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maikunis, G.; Panayiotidis, A.; Burke, L. Changing the nature of lectures using a personal response system. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2009, 46, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, D.M.; Collura, M.J. Evaluating the Effectiveness of a Personal Response System in the Classroom. Teach. Psychol. 2009, 36, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morling, B.; McAuliffe, M.; Cohen, L.; DiLorenzo, T.M. Efficacy of Personal Response Systems (“Clickers”) in Large, Introductory Psychology Classes. Teach. Psychol. 2008, 35, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, J. Clickers in the Large Classroom: Current Research and Best-Practice Tips. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2017, 6, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A. The wear out effect of a game-based student response system. Comput. Educ. 2015, 82, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison, S.; Wright, A.; Milner, R. Using clickers to improve student engagement and performance in an introductory biochemistry class. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2009, 37, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doucet, M.; Vrins, A.; Harvey, D. Effect of using an audience response system on learning environment, motivation and long-term retention, during case-discussions in a large group of undergraduate veterinary clinical pharmacology students. Med. Teach. 2009, 31, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.; Healy, A.; Kole, J.; Bourne, L. Conserving time in the classroom: The clicker technique. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. Sch. 2011, 64, 1457–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, K.; Crowley, M. Effective learning in science: The use of personal response systems with a wide range of audiences. Comput. Educ. 2011, 56, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, P.K.; Richardson, A.; Oprescu, F.; McDonald, C. Mobile-phone-based classroom response systems: Students’ perceptions of engagement and learning in a large undergraduate course. Int. J. Math. Educ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 44, 1160–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voelkel, S.; Bennett, D. New uses for a familiar technology: Introducing mobile phone polling in large classes. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2014, 51, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J.; Chin, K.; Williams, B. Using the flipped classroom to improve student engagement and to prepare graduates to meet maritime industry requirements: A focus on maritime education. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 2014, 13, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, C. Language, relationships and skills in mixed-nationality Active Learning classrooms. Stud. High. Educ. 2015, 42, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, J.M.; Coulthard, R. Towards an Analysis of Discourse: The English Used by Teachers and Pupils; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, S.; Sert, O. Mediating L2 learning through classroom interaction. In Second Handbook of English Language Teaching; Gao, X., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).