Abstract

Globally, education systems are faced with dual workforce crises: a shortage of teachers and a lack of affordable housing. Attracting and retaining teachers through improved renumeration, working conditions, and quality preparation have been central. However, initiatives to attract and retain teachers mean little if the workforce cannot find appropriate (quality and affordable) housing within commuting distance to their workplaces. The present study undertakes a scoping review of research on the intersection of housing and the school education workforce. Specifically, we examine the volume, variety, and characteristics of evidence through the question of ‘What empirical studies have been published on the relationship between housing and the school education workforce?’ Online databases were used to identify 23 studies published in 2000–2024 from Australia, China, England, Kenya, Malaysia, New Zealand, Tanzania, Uganda, the UK, and the USA. Publications drew on a range of methods and housing was rarely the focal unit of analysis. This study finds that beyond establishing unaffordability through salary and housing costs ratios, and the peripheral inclusion of housing issues in studies, there is insufficient published peer reviewed evidence available to purposefully inform and measure interventions. Greater interdisciplinarity is required in research to highlight the complexity of issues at the intersection of housing (availability, affordability, and distance from workplaces) and workforce distribution. More rigorous data should be collected to support robust reporting on the state of housing for the school education workforce to deliver the type of evidence necessary to develop targeted and tailored interventions to improve outcomes for the workforce and ultimately students.

1. Introduction

On a global scale, the school education workforce is experiencing concurrent crises—a teacher shortage, coupled with housing unaffordability in many cities and regions. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [1] modeling indicates a global shortfall of 44 million teachers by 2030. At the same time, post-2008 global financial crisis megatrends of accelerated (re)urbanization of capital and people, the provision of cheap credit, and the rise of intra-society inequities has led to an international housing crisis [2]. For those attracted to and retained in teaching (as with other essential workers), salaries have not kept up within inflation and heated housing markets mean that some schools—including those in housing market areas that are desirable to higher income households—may be experiencing difficulties in finding staff [3,4,5].

In many parts of the world, the urgency and scale of the teacher shortage has meant greater attention to the attraction of people to the profession and within-school working conditions as explainers of workforce performance and retention, e.g., [6,7]. However, initiatives to attract and retain teachers mean little if teachers cannot afford to live within commuting distance of their workplace. Despite this, workforce distribution, housing affordability, and transportation costs, factors central to the accessibility of schools, remain a policy blind spot. It is unclear what kind of information is available to governments, school systems, professional associations, teachers’ unions, educators, and related industries (e.g., banks, superannuation firms) about the intersection of housing and the school education workforce. For that reason, a scoping review was conducted to systematically map the research on the topic to identify any existing gaps in knowledge and chart a path for further research.

Identifying 23 studies referring to housing and the school teaching workforce, we found that overall, a lack of robust evidence on teacher housing interventions beyond pointing out the unaffordability of many locations poses a significant challenge for government, industry representatives and advocacy organizations, schools, and even educators. Based on the limited identified literature in this study, there is insufficient evidence that a systematic review is required. The topic of housing is more likely to come up as an additional issue or tangent when studying another issue for educators or districts. We argue that greater targeted and tailored studies, possibly interdisciplinary, are required to understand the intersection of housing and the school education workforce and deliver the breadth of data and evidence required to develop effective interventions. The political, economic, and cultural capital necessary to deliver the scale—both volume and geographic spread—of housing that the school education workforce requires is substantial. Existing work on the topic has laid the foundations, but more work needs to be conducted and quickly if nations are to avoid the prospect of schools without teachers solely because they are inaccessible.

2. Materials and Methods

This paper reports on a scoping study, an approach made popular by Arksey and O’Malley [8], and extended by many others, e.g., [9,10,11]. Scoping reviews can be conducted to meet various objectives, including examining the volume, variety, and characteristics of evidence on a topic, determining the value of undertaking a systemic review, summarizing findings from a body of knowledge that is heterogeneous in methods or interdisciplinary, or identifying gaps in the literature. In this paper, our goal was to examine the volume, variety, and characteristics of evidence through the question of ‘What empirical studies have been published on the relationship between housing and the school education workforce’? Our protocol was drafted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis protocols extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist [12], which was revised by the research team.

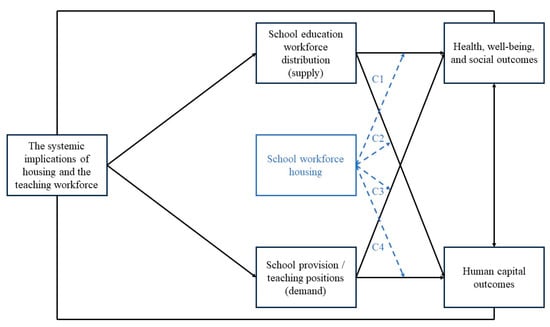

Peer-reviewed journal articles were included if they were published in the period 2000–2024, written in English, were either conceptual or empirical, and described their conceptualization of the relationship between housing and the school education workforce. To the best of our knowledge there are no prior review studies of the topic, including in the time prior to our sampling (pre-2000). There were no limitations on data types (e.g., quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods) to ensure maximum diversity in the corpus. Papers were excluded if they did not fit into the conceptual framework of the review or focused on generic essential worker housing without mentioning teachers or school-based educators. In seeking to understand the interplay of housing and the school education workforce, we conceptualized the relationships (a priori) as depicted in Figure 1. We see the distribution of the school education workforce (supply) and the number of teaching positions to be filled (demand) to be the orthodox input variables. Social, economic, cultural, health, well-being, and human capital development are applied as outcome variables. As distribution is geospatial, we consider housing and transportation to link supply and demand (blue box and dashed lines) with an effect on outcomes.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for establishing the underlying generative assumptions of research identified in the review (source: authors).

To identify potentially relevant research, the following databases were searched from 2000 through to the time of study (January 2024): EBSCO, ProQuest, and Scopus. The search strategies were drafted by a team member, LM, in collaboration with an experienced research librarian at UNSW Sydney. Further refinement was undertaken through team discussion. Final syntax for the respective databases can be found below.

EBSCO: TI (“housing*” OR “housing affordability” OR “affordable housing” OR “workforce housing” OR “teacher housing” OR “key worker housing” OR “essential worker housing”) AND (“teacher*” OR “educator*” OR “school education workforce” OR “key worker*” OR “essential worker*”)) OR AB (“housing*” OR “housing affordability” OR “affordable housing” OR “workforce housing” OR “teacher housing” OR “key worker housing” OR “essential worker housing”) n5 (“teacher*” OR “educator*” OR “school education workforce” OR “key worker*” OR “essential worker*”).

PROQUEST: title ((“housing*” OR “housing affordability” OR “affordable housing” OR “workforce housing” OR “teacher housing” OR “key worker housing” OR “essential worker housing”) AND (“teacher*” OR “educator*” OR “school education workforce” OR “key worker*” OR “essential worker*”)) OR abstract ((“housing*” OR “housing affordability” OR “affordable housing” OR “workforce housing” OR “teacher housing” OR “key worker housing” OR “essential worker housing”) n/5 (“teacher*” OR “educator*” OR “school education workforce” OR “key worker*” OR “essential worker*”)).

SCOPUS: TITLE ((“housing*” OR ”housing affordability” OR ”affordable housing” OR ”workforce housing” OR ”teacher housing” OR ”key worker housing” OR ”essential worker housing”) AND (”teacher*” OR ”educator*” OR ”school education workforce” OR ”key worker*” OR ”essential worker*”)) OR ABS ((“housing*” OR ”housing affordability” OR ”affordable housing” OR ”workforce housing” OR ”teacher housing” OR ”key worker housing” OR ”essential worker housing”) W/5 (”teacher*” OR ”educator*” OR ”school education workforce” OR ”key worker*” OR ”essential worker*”)).

The final search results were exported into EndNote. As a robustness check, major publishing houses (Elsevier, Springer, Taylor and Francis, Emerald, and Wiley—using the same or platform-sensitive search syntax) were searched for additional articles. A final check was conducted using Google Scholar (“teacher housing” AND ‘teacher shortage”), ResearchGate (“teacher housing” AND “teacher shortage”), and citation tracking.

To increase consistency among reviewers, prior to commencing the review, two reviewers screened the same five publications, discussed the results, and amended the screening and data extraction approach before commencing this review. Two reviewers, LM and SE, worked independently in each phase of the review before coming together to discuss results and continuously update the approach in an iterative process. To demonstrate the rigor and effectiveness of this process, a measure of inter-rater reliability was employed. Moving beyond a mere percentage of agreement, Cohen’s [13] kappa (κ), a well-recognized benchmark for inter-rater reliability with nominal categories and two raters, was used. The cohen_kappa_score() function from sklearn library (scikit-learn, 1.4.0 module) in Python 3.12 was used to calculate the value, with reviewers operating at a κ = 0.79 level of agreement. This is a ‘substantial’ level of agreement between raters [14,15]. Disagreements were resolved on study selection and data extraction by consensus following discussion between reviewers.

A data-charting form was jointly developed by two reviewers, LM and SE, and checked by team members CG, KCM, and CJP to determine which variables to extract. The reviewers charted the data tool designed for this study. The tool captured the relevant information on key study characteristics (source, year, country, aim, unit of analysis, design, methods, data source, sampling, sample size, measures, timeframe, casual logic, key findings). To establish the underlying generative assumption (causal logic) of the intersection of housing and the school education workforce, the two reviewers coded independently, before meeting to discuss any disagreements. Any unresolved coding was adjudicated by a third reviewer from the team.

Our focus on the existing evidence and the underlying assumptions of knowledge claims meant we aimed to concurrently explore the content and quality of reporting of published research. To establish quality, we drew on the Nature portfolio reporting summary checklist for the behavioral and social sciences (https://www.nature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-Apr-2023-flat.pdf, accessed on 10 March 2024) as a benchmark. This checklist was created for the purpose of improving the reproducibility of the work published in Nature and providing a structure for consistency and transparency in (social) science. Our dual focus on content and quality of reporting allowed us to generate a descriptive and explanatory synthesis of the existing knowledge base on the intersection of housing and the school education workforce and chart a path forward for research.

3. Results

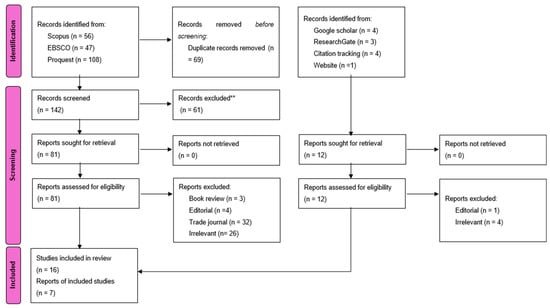

After duplicates were removed, a total of 142 records were identified from the searches of electronic databases (EBSCO, Proquest, and Scopus). Based on an assessment of the title and abstract, 61 were excluded, with 81 full-text articles to be retrieved and assessed for eligibility. Of these, 65 were excluded for the following reasons: 32 were in trade journals rather than scholarly outlets, 26 were deemed irrelevant, and 7 were not considered to be original empirical research (e.g., editorials, book reviews). The remaining 16 studies were considered eligible for this review. Supplementing these 16, a further 12 studies were identified in the robustness check. After 5 were excluded (irrelevant or editorial), 7 were added. The final total of records included in this review was 23 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PRISMA extension for scoping reviews diagram (source: [16]).

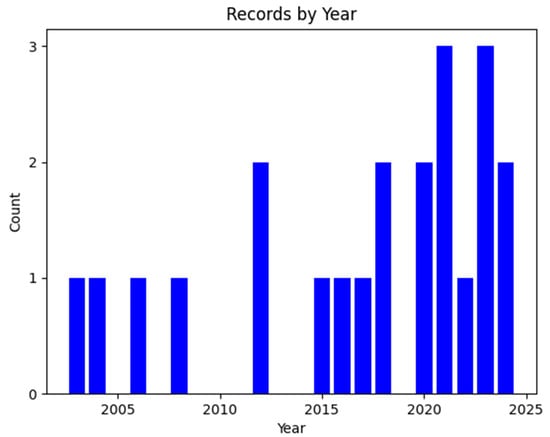

Of these 23 studies, nine different countries were represented, the USA (n = 5), UK/England (n = 4), Australia (n = 3), Uganda (n = 3), New Zealand (n = 2), Tanzania (n = 2), China (n = 2), and single studies from Kenya and Maylasia. Fourteen focused exclusively on teachers (61%), while the other 39% (n = 9) used the broader key/essential workers and mentioned teachers. There has been an uptick in papers in the last seven years, although no year featured more than three papers (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Records by year (source: authors).

Mindful of the limitations of conflating outlet ranking with the quality of individual papers, using the international ranking quartiles of Scimago Journal and Country Rank (https://www.scimagojr.com/, accessed on 10 March 2024), and taking the highest rank in any discipline for interdisciplinary coded journals, of the 20 identified journal articles (excluding the three reports), 40% (n = 8) appeared in quartile one journals, 15% (n = 3) in Q2, 10% (n = 2) in Q3, 5% (n = 1) in Q4, and 30% (n = 6) in unranked outlets.

While a small number of papers had explicit aims of investigating housing affordability and teachers, e.g., [3,17,18], in most studies, issues of housing and the school education workforce were peripheral to other matters. These included reducing or optimizing staff movements [19,20]; how best to use land or existing buildings [21,22,23]; how infrastructure (including housing) impacts identity, commitment to the profession, or working conditions [24,25,26,27]; or were aimed at all key/essential workers, of which teachers are a sub-category [4,5,28,29,30,31,32,33]. A few outlier examples included linking housing to broader land use [34], purchasing decisions [35], or advocating for a particular type of construction to address the lack of housing issue [36]. A single paper sought to link housing with teacher performance [18].

The research design of studies fell into two overarching categories, surveys of large areas (e.g., states, nations, n = 4) or the most common approach being case studies of specific regions or initiatives (n = 19). The corresponding sampling approach was frequently purposive, even if not explicitly named as such, with single examples of stratification [19] or randomization [35]. There is a relatively even spread of method orientations across quantitative (n = 8), qualitative (n = 8), and mixed-method (n = 6) approaches. The use of large-scale publicly available data was a common feature (n = 9), as with interviews or focus groups (n = 9) and to a lesser extent questionnaires (n = 4), and archival or historical analysis (n = 2). Sample sizes varied from many data points over an extended period, from the analysis of publicly available data through to interviewing two teachers. As a result, calculating an aggregated mean is not useful.

One of the more concerning issues with the identified studies is the under-reporting of methodological details (as per the Nature checklist). In a few cases, it was unclear what methods were used (n = 2), and in many others, the exact n was not reported (n = 12), nor were the specific measures or assumptions articulated. Sometimes, the description of the analytical work was limited to ‘thematic analysis’ or ‘inductive analysis’, with no explicit articulation of data reduction strategies. Overall, the disclosure of the study description, research sample, sampling strategy, data collection, timing, data exclusions, non-participation, and randomization (as per the Nature portfolio reporting checklist) was poorly documented—possibly linked to the quality of outlet observation.

Despite some papers tracking affordability over time or commuting distance, studies were more focused on description rather than explanation/prediction. They would describe often dire situations of unaffordability of housing but provide little, if any, explanation of how things came to be or what can be done apart from making more housing available. Large-scale surveys of cost and salary ratios demonstrated the increasing unaffordability of specific areas but had few, if any, evidence-based mechanisms for addressing the issues. Case studies of specific initiatives or examples described the impact of those on local populations with little consideration of the scalability of such reforms.

Heterogeneity in the study aims makes it difficult to aggregate any measures or synthesize outcomes and findings. Housing affordability measures, such as the ratio of indicative salary to mean or median housing costs in an area, were common (n = 7). Other than the use of large-scale data, the under-reporting of conceptual and instrument (including interview/focus group schedules) development coupled with minimal (if any) information on data reduction and analysis poses a significant threat to the credibility of research on the topic.

Although it is difficult to parse workforce well-being and performance, our conceptual framework sought to identify the underlying generative assumptions between major constructs (input variables of workforce distribution and school provision) and output variables (workforce well-being or performance) as moderated by housing and transportation costs. Studies could be coded against multiple categories. The two dominant logics in the identified studies (see Table 1) are that greater workforce distribution (meaning further commutes) or sub-optimal accommodation has a negative impact on workforce well-being (n = 13), and the provision of schooling is compromised when the workforce cannot find affordable housing nearby (n = 8).

Table 1.

Causal logics present in the identified studies (source: authors).

There is a diverse range of findings presented in the identified studies. The unaffordability of areas for teachers, as with other essential workers, especially in high demand locations, is not new—although the gap may be widening. Transparency in the data sources and the analysis of housing costs and salaries make this type of study the most robust evidence available on the intersection of housing and the teacher workforce. Reporting based on as little as a single item in a previously unvalidated questionnaire, a small number of targeted interviews, or advocating for initiatives or products without any formal evaluation or longitudinal analysis of impact are not considered high-quality evidence.

In sum, the intersection of housing and the teacher workforce remains a peripheral issue in the knowledge base of education. Apart from large-scale surveys of housing cost and salary ratios, housing is more likely to come up tangentially in studies, meaning there are few robust metrics or concepts to inform interventions. Conceptually, housing is most often conceived as having an indirect effect on school provision and outcomes through workforce well-being. To this point, there are no empirically validated measures beyond the ratios of salary to housing costs, and transportation costs to access schools in unaffordable markets are largely overlooked. The reporting of analytical approaches has not always been at the level of detail expected, limiting robustness and not providing the level of evidence required by policy makers.

4. Discussion

In this scoping review, we identified 23 studies investigating the intersection of housing and the school education workforce published between 2000 and 2024. Our findings indicate a paucity of research specifically focusing on housing or evaluating the impact of initiatives. What was more likely were large-scale surveys of publicly available data to highlight unaffordability, e.g., [3,4,5,28,29], or small-scale case studies of specific initiatives using interviews, focus groups, or participant observation, e.g., [21,22,23]. Although important and feasible, these data generation or curation strategies only partially address the need for viable options for addressing the dual crises of housing affordability and the teacher shortage.

The number of studies considering housing has increased (see Figure 3), although it remains relatively low given the volume of the literature on education produced annually. Across this emerging body of evidence, there is consensus on the need for systemic-level reforms capable of reducing massive economic and wellbeing inequities and multi-generational damage to workforce prosperity. Existing models, those responsible for current practice, will only be replaced if there is a viable alternative. Based on the evidence identified in this scoping study, constructing a feasible alternative is problematic. In many countries grappling with the expansion of access to education for their populations, there are many confounding variables creating noise in the data. The availability of quality housing in some cases is about stock and the need for a greater number of dwellings in locations. Elsewhere, the issue is about the affordability of housing. In both cases, the disciplinary knowledge required to understand the complexity of these issues is beyond education. Urban science (geography, city planning, and demography), transport modeling, and housing economics (e.g., house prices) would be of assistance in identifying crucial policy issues and reducing noise in the data. Furthermore, interdisciplinary analysis of the intersection of housing and the school education workforce will be foundational to generating policy concepts (e.g., workplace accessibility) and establishing parameters and measures for targeted and tailored interventions. Without an approach to providing viable alternatives and the mechanisms through which they can be achieved, there is unlikely to be any change in existing practices.

Teachers are required for schools to function. Access to high-quality and affordable housing within commuting distance of work is important for teacher well-being [19,21,24,25], can be a drawcard for attracting people to hard-to-staff schools [20], and is important for regional or community development [22,23,34]. There is ample evidence that salaries are not keeping up with rising housing costs [3,4,5,27,28,29]. The provision of or access to housing is part of teachers’ working conditions [26] and this makes it fundamental to governments’ and school systems’ responses to the teacher shortage.

A report [17] and accompanying handbook [37] from the Center for Cities + Schools (UC Berkeley), cityLAB (UCLA), and the Terner Center for Housing Innovation (UC Berkeley) have provided substantial advice for school boards, administrators, and community members to advocate for and advance the development of education workforce housing on underutilized school land in California. What they highlight, however, is the interdisciplinarity that is required to understand the intersection of housing and the school education workforce and the breadth of data and evidence required to develop effective interventions. The issues of how to deliver the scale of housing required to accommodate teachers (without forcing them into teacher housing), particularly in cities, and the necessary capital for such a large scale (both in number and geographic spread) are substantial. The economic modeling of such projects and the policy and legislative requirements built on the provision of schooling for a population are further considerations. The existing interdisciplinarity in the knowledge base, as evidenced in this scoping study, is more about not quite fitting any one discipline than it is a comprehensive description of what is happening and what needs to be done to address the complexity of housing and the school education workforce.

5. Limitations

As with all projects, this scoping study is not without limitations. First, a review is only as good as the studies available on the topic. Inconsistent quality of reporting and heterogeneity in focus has diluted the strength of what can and what cannot be said about the intersection of housing and the school education workforce. It is, at this point, difficult to aggregate key measures or indices to build a cohesive and persuasive argument for policy makers.

Analytically, the intersection of housing and the teacher workforce is arguably a sub-set within a broader discussion of key or essential workers. The difficulties in parsing teachers within generic key or essential worker research was problematic. Unless teachers were explicitly mentioned, we had to exclude studies. At the same time, housing often came up as a peripheral issue in studies and the implications were not explored in any depth. As a result, there is a blurring of the boundaries of analytical categories that will only be sorted through a greater critical mass of studies and the development of clearly identified and acknowledged concepts.

Finally, the core work of this scoping study was undertaken during a summer internship awarded to LM. To make it feasible for such a post, decisions regarding scale and scope needed to factor in the limitations of time. While further work was conducted to translate the data generated into this manuscript, the time is a limitation.

6. Conclusions

Housing the school education workforce is an educational issue. For the effective functioning of school systems, it should be viewed as necessary infrastructure with ‘an adequate supply assured through planning and implementation just as communities assure the availability of adequate retail, office, industry, schools, or streets’ [38]. The lack of robust evidence on teacher housing interventions—beyond pointing out the unaffordability of many locations—appears to pose a significant challenge for governments, systems, schools, and educators. Based on this scoping study, there is minimal, if any, evidence that undertaking a systematic review of the topic would be appropriate or necessary. Put simply, there is insufficient evidence to guide the nature of educator housing interventions. There is also limited evidence to describe the experiences of teachers on the lack of housing—a vital component of the complexity of housing interventions and an integral part of any implementation and evaluation of interventions. As a result, there is a need for high-quality interdisciplinary research blending education and urban science, transport modeling, and housing economics, among others, to determine what type of interventions are feasible and may be of benefit for the school education workforce and to help guide governments and systems on how best to deliver them. Research using geospatial analysis to demonstrate workforce distribution, integrated with location-sensitive housing and transportation costs over time, can be used to inform policy interventions and predict forthcoming issues when combined with population projections. With research indicating that it can take a decade from decisions to the delivery of large-scale infrastructure projects for teacher housing [17], the window is quickly narrowing to prevent the prospect of schools without teachers solely because housing made them inaccessible.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M. and S.E.; methodology, L.M. and S.E.; formal analysis, L.M. and S.E.; investigation, L.M.; resources, S.E.; data curation, L.M. and S.E.; writing—original draft preparation, S.E. and L.M.; writing—review and editing, C.G., K.M. and C.J.P.; visualization, S.E.; supervision, S.E.; project administration, L.M.; funding acquisition, S.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research reported in this paper was partially funded by a Gonski Institute for Education Summer Internship for LM to work with SE. The funder has no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No applicable as this study did not involve human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UNESCO. The Teachers We Need for the Education We Want: The Global Imperative to Reverse the Teacher Shortage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wetzstein, S. The global urban housing affordability crisis. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 3159–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eacott, S. The systemic implications of housing affordability for the teacher shortage: The case of New South Wales, Australia. Aust. Educ. Res. 2024, 51, 733–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, C.; Nasreen, Z.; Gurran, N. Housing key workers: Scoping challenges, aspirations, and policy responses for Australian cities. In AHURI Final Report; University of Sydney: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, C.; Nasreen, Z.; Gurran, N. Tracking the Housing Situation, Commuting Patterns and Affordability Challenges of Essential Workers; University of Sydney and Hope Housing: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Madalińska-Michalak, J. The Erosion of Teachers’ Salaries and its Impact on the Attractiveness of the Teaching Profession in Europe. Seminar 2023, 29, 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, M.; McGrath-Champ, S.; Wilson, R. Teacher attributions of workload increase in public sector schools: Reflections on change and policy development. J. Educ. Change 2023, 24, 971–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Colquhoun, H.; Garritty, C.M.; Hempel, S.; Horsley, T.; Langlois, E.V.; Lillie, E.; O’Brien, K.K.; Tunçalp, Ö.; et al. Scoping reviews: Reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Baxter, L.; Tricco, A.C.; Straus, S.; Wickerson, L.; Nayar, A.; Moher, D.; O’Malley, L. Advancing scoping study methodology: A web-based survey and consultation of perceptions on terminology, definition and methodological steps. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E. Measurement reliability and agreement in psychiatry. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 1998, 7, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Cities + Schools, cityLAB, and Terner Center for Housing Innovation. Education Workforce Housing in California: Developing the 21st Century Public School Campus; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Justus, T. Relationship Between Teacher’ Housing And Performance In Primary Schools In Kamwezi Sub County, Rukiga District, Uganda. Metrop. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 2024, 3, 369–378. [Google Scholar]

- Ariko, C.O.; Othuon, L.O.A. Minimizing teacher transfer requests: A study of Suba district secondary schools, Kenya. Int. J. Educ. Adm. Policy Stud. 2012, 4, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Guilin, Y. Teacher Exchange and Rotation is Not Equivalent to Partner Assistance. Chin. Educ. Soc. 2018, 51, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellery, P.J.; Ellery, J.; Borkowsky, M. Toward a Theoretical Understanding of Placemaking. Int. J. Community Well-Being 2021, 4, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, I. Community participation as a tool for conservation planning and historic preservation: The case of “Community As A Campus” (CAAC). J. Hous. Built Environ. 2018, 33, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, I. Repurposing a historic school building as a teacher’s village: Exploring the connection between school closures, housing affordability, and community goals in a gentrifying neighborhood. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2020, 13, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrent, G. School infrastructure as a predictor of teacher identity construction in Tanzania: The lesson from secondary education enactment policy. Afr. Stud. 2020, 79, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkumbo, K.A. Teachers commitment to, and experience of, the teaching profession in Tanzania: Findings of focus groups research. Int. Educ. Stud. 2012, 5, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namara, R.B.; Kasaija, J. Teachers’ Protest Movements and Prospects for Teachers Improved Welfare in Uganda. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2016, 4, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Singleton, E.; Roberts, T. The Impact of Teacher Pay on Teacher Poverty: Teacher Shortage and Economic Concerns. Curr. Urban Stud. 2023, 11, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, N. Assessing the need for key-worker housing: A case study of Cambridge. Town Plan. Rev. 2003, 74, 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, N.; Monk, S. Job-Housing Mismatch: Affordability Crisis in Surrey, South East England. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2006, 38, 1115–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raco, M. Key Worker Housing, Welfare Reform and the New Spatial Policy in England. Reg. Stud. 2008, 42, 737–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Xiong, C.; Cheung, K.S.; Filippova, O. Understanding the Spatial Effects of Unaffordable Housing Using the Commuting Patterns of Workers in the New Zealand Integrated Data Infrastructure. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Cheung, K.S.; Filippova, O. Spatial Mismatch and Housing Affordability of Key Workers: Evidence from Auckland. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2024, 150, 04023053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, F.N.; Hearne, R. Housing for essential service workers during an oil boom: Opportunities and policy implications. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2017, 32, 755–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Sheng, T.; Shi, X.; Fang, B.; Lu, X.; Zhou, X. The Relationship between Housing Price, Teacher Salary Improvement, and Sustainable Regional Economic Development. Land 2022, 11, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.; Syed Mohamad, S.F. Factors Influencing the Purchase Decision of Affordable Housing Among Middle Income Earner: A Case Study of School teachers in Malaysia. Malays. J. Sci. Health Technol. 2020, 7, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, A.; Todd, S. New developments for key worker housing in the UK. Struct. Surv. 2004, 22, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- cityLAB. Education Workforce Housing in California: The Handbook; cityLAB, University of California: Los Angeles CA, USA, 2022; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Kushner, J.A. Affordable Housing as Infrastructure in the Time of Global Warming. Urban Lawyer 2010, 42/43, 179–221. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).