Examining the Influence of Secondary Math and Science Teacher Preparation Programs on Graduates’ Instructional Quality and Persistence in Teaching

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Literature

2.1. Research into Features of Teacher Preparation Programs

2.2. Teaching Quality Understood as Instructional Rigor

2.3. Teacher Persistence

- (1)

- Stayers: describes current K-12 classroom teachers at a specific school.

- (2)

- Leavers: describes K-12 teachers who have left the classroom.

- (3)

- Movers: describes current K-12 teachers who move schools.

3. Research Questions

- (1)

- and the quality of novice teachers’ math and science instruction (as measured by the rigor of their planning and enactment)?

- (2)

- and their graduates’ persistence in teaching?

4. Methods

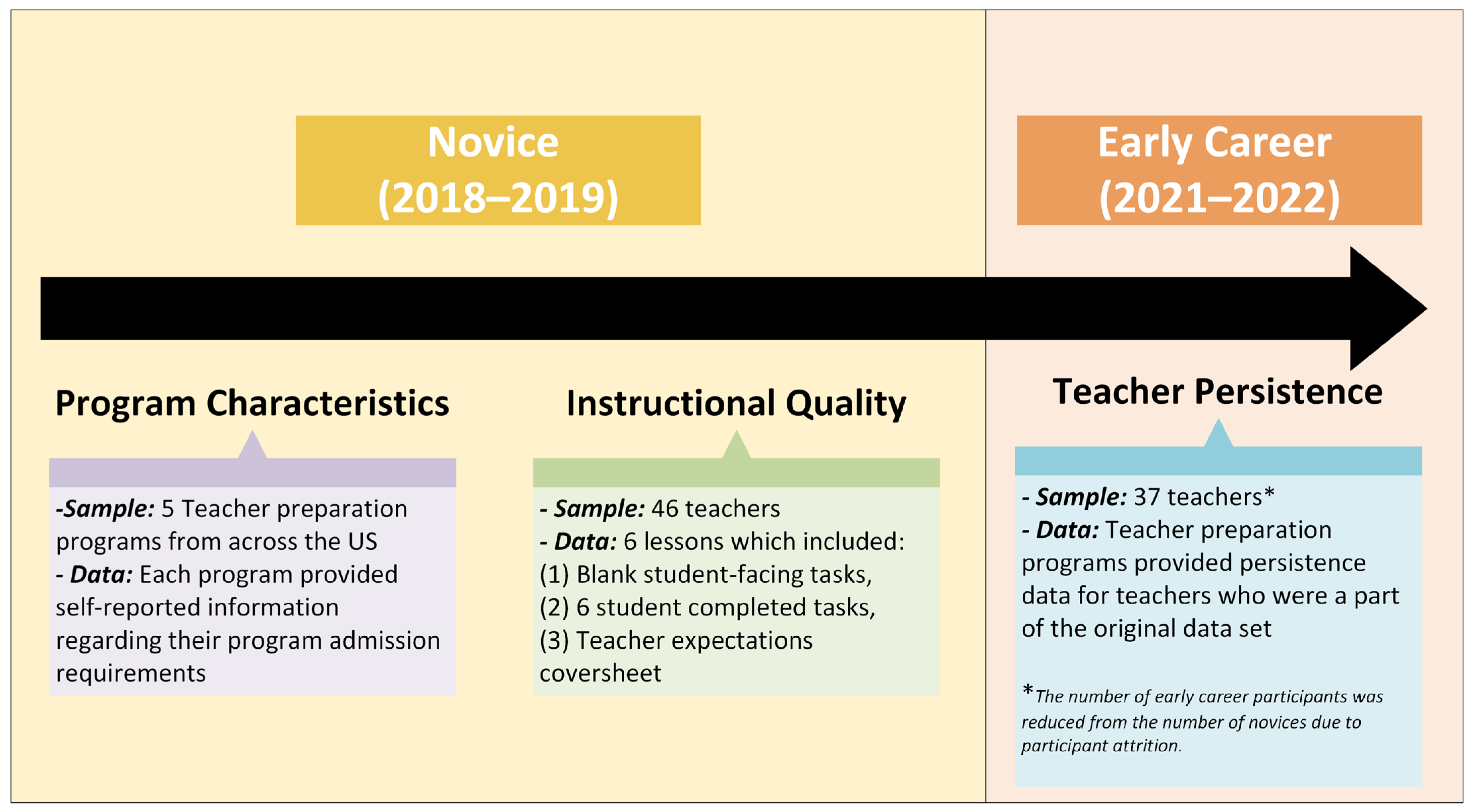

4.1. Programs and Participants

4.2. Data Sources and Analysis

4.2.1. Teacher Preparation Program Structure

4.2.2. Instructional Quality

Instructional Quality Data

- (1)

- The potential of rigor as designed.

- (2)

- The rigor with which the task was implemented (as the task was assigned and assessed).

- (3)

- The rigor is found in the kind and level of thinking teachers expect of their students.

- cover sheet that described the teacher’s goals and expectations for students learning from the task,

- The assigned task (or the student-facing work),

- Six examples of student work on the task, along with the teacher’s assessment of the quality of their work (including two from students who excelled at the task, two who adequately completed the task, and two who underperformed on the task) and teacher evaluations and comments on the student work.

| Rubric | Description | Data |

|---|---|---|

| R-1: Potential of the Task | Explores the potential of a task for engaging students in different kinds and levels of thinking in science or math, allowing for differentiation between tasks regarding the disciplinary activities that students engage in. | Instructional task assigned to students (i.e., worksheets and problems in texts). |

| R-2: Implementation of the Task | Explores the level and kind of thinking a majority of the students engaged in as they completed the task, highlighting instructional factors that maintain or reduce students’ thinking throughout implementation. | Artifacts of students’ work on the assigned task (differentiated by the teacher—2 low, 2 medium, and 2 high). |

| R-3: Teacher’s Expectations | Explores the degree of rigorous thinking that science and math teachers expect from students throughout the lesson and in assignments. | Coversheet, which included teachers’ directions to students and grading expectations, including any rubric they shared with the students. |

Instructional Quality Data Analysis

- Rubric 1, or Potential of the Task: describes the potential demand of the task on students’ thinking (R-1 Potential).

- Rubric 2, or Implementation of the Task: describes the level and kind of thinking required from students as they complete the assigned task (R-2 Implementation).

- Rubric 3, or Teacher’s Expectations: describes the degree of rigorous thinking teachers expect from students as they complete the task (R-3 Expectations).

- Absent (no math or science activity required)—students are not engaged in math or science activity.

- Low—students use memorized procedures, formulas, or definitions, or where students are engaged in a preset procedure to arrive at an answer.

- Moderate—students are asked to engage in complex thinking but are not expected to describe it.

- High—students engage in exploring and understanding the nature of math or science.

4.2.3. Teacher Persistence

- (1)

- Active: teachers in this category are current teachers in K-12 teaching positions.

- (2)

- Reserve: Teachers are not currently teaching in K-12 settings and can be separated into those taking a break in service and those who have begun providing advancement to the education field. Teachers taking a break in service see the break as temporary and intend to return to the same or a similar position. Those teachers providing advancement to the education field have joined an education-related position for which teacher certification has value (e.g., administration, higher education, or informal education).

- (3)

- Attritted: teachers leaving the profession with no intent to return.

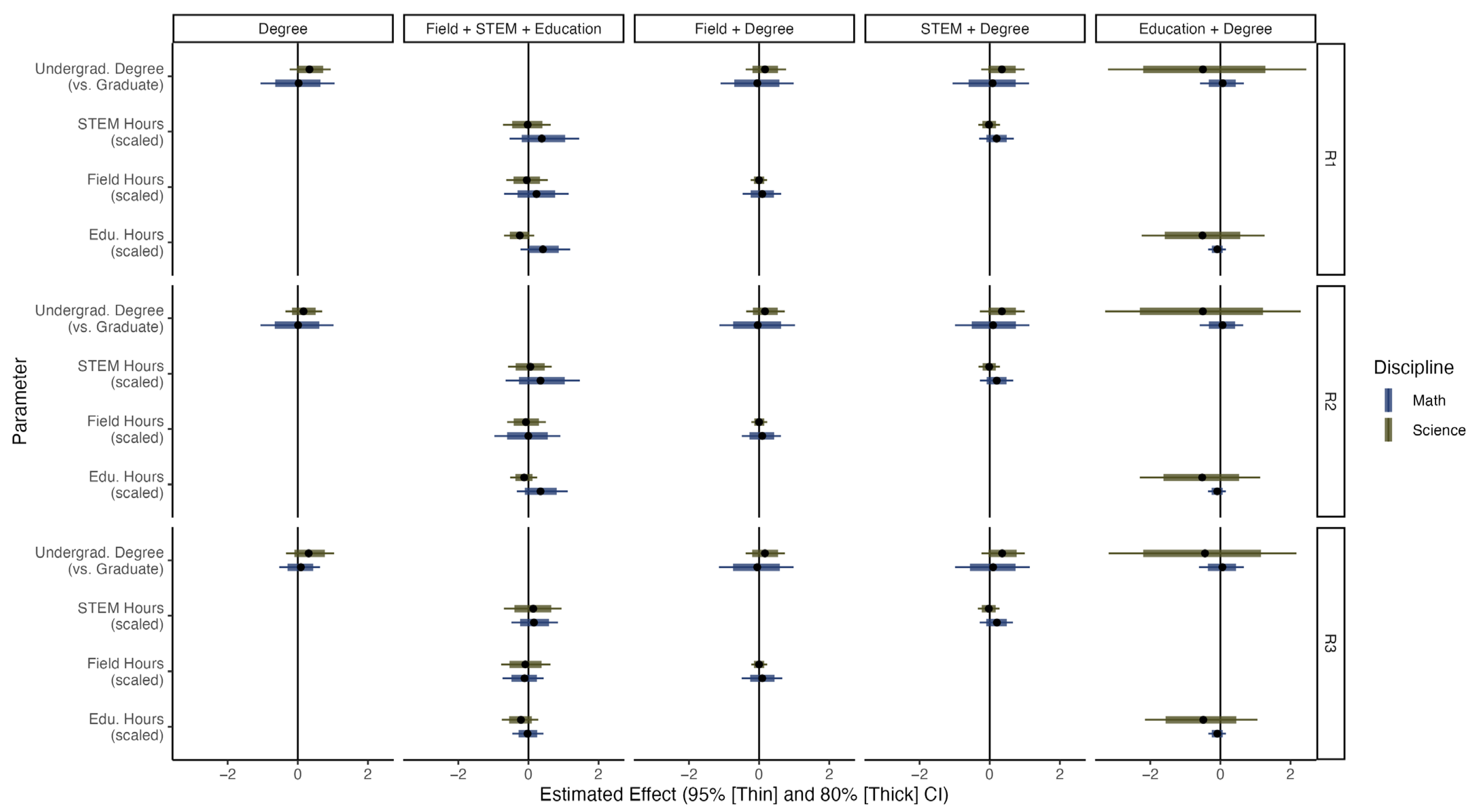

4.2.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Findings

5.1. Teacher Preparation Program Characteristics

5.2. Teacher Preparation Program and Instructional Rigor

5.3. Teacher Persistence

5.4. Modeling Influence of Program Structure on Teacher Persistence

5.5. Structure on Teachers’ Instructional Rigor

6. Discussion

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions and Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Characteristics of Preparation Program Interview Protocol |

|

Appendix B. Example IQA- Categories for a Math Task Set

| Rubric | Category of Academic Rigor | Score Descriptor | Coder’s Comments |

| R1 | Moderate | Apply Procedures: The task has the potential to engage students in complex thinking (such as finding relations, analyzing information, and generalizing to a broader idea), but the task does not ask for students’ reasoning. The emphasis follows a prescribed procedure for sensemaking, but without explanation of reasoning. | The task asks students to create multiple representations, but not to explain the connection between them. In addition, students are asked to interpret which is the better deal, but are then led step-by-step on how to determine that. |

| R2 | Low | Rote/Procedural: Students’ work indicated that they engaged with the task at a procedural level, applying prescribed procedures to provide the correct answer, showing steps, or students reproduced memorized information (facts, rules, formulas, or definitions). | Most of the student work was uniform in nature and at the procedural level. |

| R3 | Low | Rote/Procedural: Teachers’ expectations focused on student learning, but not complex thinking (e.g., expecting use of a specific problem-solving strategy, or expecting short answers based on memorized facts, rules, or formulas), or teacher expectations were not focused on mathematics (i.e., following directions, neat work, and student effort). | Teachers’ expectations focused on students’ completion of work. |

Appendix C. Example IQA-SAR Categories for a Science Task Set

| Rubric | Category of Academic Rigor | Score Descriptor | Coder’s Comments |

| R1 | Moderate | Learning About: The task has the potential to engage students in complex thinking and high-level cognitive processes (such as finding relations, analyzing information, an dgeneralizing to a broader idea), but science content or scientific practices are forefronted. The emphasis is on learning about science content or practices. | Task asked students to use multiple representations to show their work and correct answers, but did not ask students to make connections between them. |

| R2 | Low | Rote/Procedural: Students’ work indicated engagement in procedures that led them to complete the task without knowing (or needing to know) why and how the script led to that answer, and indicated students’ use of skills/mechanics associated with the practices or students reproduced memorized information (facts, rules, formulas, or definitions). | Majority of students used the same procedure following a template that the teacher said they discussed in class. |

| R3 | Low | Rote/Procedural: Teachers’ expectations focused on student learning, but not complex thinking (e.g., correct use of prescribed procedure), or teachers’ expectations were not focused on science activity (i.e., following directions, neat work, and student effort). | Teacher expected students to use the specific procedure discussed in class to show their work and correct answers. |

Appendix D. Interview Protocol for Teacher Persistence

- Personal

- ◦

- Why did you choose to become a teacher initially?

- ◦

- What are some of the things you enjoy or find satisfying about being a teacher?

- ◦

- What are some of the things about being a teacher that you don’t enjoy or that you don’t find satisfying?

- ◦

- Where did you complete your early years in teaching? Are you still there?

- ◦

- How long do you plan to continue to teach?

- ◦

- Have you considered leaving your school? The profession?

- ◦

- What would get you to stay? Or what prompted you to leave?

- Program

- ◦

- What role do you think your program played in the type of mathematics/science instruction you currently use with your students?

- ◦

- Also, what was your opinion of this image of ideal mathematics/science teaching that you observed?

- ◦

- What role do you think your program played in the fact that you have continued to remain a teacher/that you left teaching?

- Contextual factors

- ◦

- Why did you choose to teach in a high-needs school?

- ◦

- How long do you foresee teaching in a high-needs school?

- ◦

- What are your reasons for continuing to teach in/leaving a high-needs school?

- ◦

- What factors will influence how long you continue teaching in a high-needs school?

- ◦

- Was there one thing that has convinced you to stay teaching in a high-needs school?

- ◦

- Think about your current school environment…

- ▪

- Classroom autonomy is the freedom that teachers have in choosing textbooks, instructional techniques, classroom discipline, and grading policies. How would you describe the autonomy you were given in your classroom? (SLM)

- ▪

- How would you describe the administrative support that you were given at your school/schools? (SLM)

- ▪

- How would you describe the behavioral climate in your classroom? At your school? (SLM)

- ▪

- Describe what your relationships at school looked like with your students.

- How well did you get to know your students?

- ◦

- If you knew them well, how did you build that knowledge/familiarity?

References

- Aaronson, D.; Barrow, L.; Sander, W. Teachers and Student Achievement in the Chicago Public High Schools. J. Labor Econ. 2007, 25, 95–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivkin, S.G.; Hanushek, E.A.; Kain, J.F. Teachers, Schools, and Academic Achievement. Econometrica 2005, 73, 417–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockoff, J.E. The impact of individual teachers on student achievement: Evidence from panel data. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, L.M.; Smith, T.M.; Phillips, K.J. Linking student achievement growth to professional development participation and changes in instruction: A longitudinal study of elementary students and teachers in Title I schools. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2013, 115, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekmekci, A.; Serrano, D.M. The Impact of Teacher Quality on Student Motivation, Achievement, and Persistence in Science and Mathematics. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, H.; Grossman, P. Learning from Teacher Observations: Challenges and Opportunities Posed by New Teacher Evaluation Systems. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2013, 83, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council Of Chief State School Officers & National Governors’ Association. Common Core State Standards Initiative. United States. 2011. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/lcwaN0010852/ (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- National Research Council. Next Generation Science Standards: For States, By States; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Primo, M.A.; Shavelson, R.J.; Hamilton, L.; Klein, S. On the evaluation of systemic science education reform: Searching for instructional sensitivity. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2002, 39, 369–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.K.; Ball, D.L. Policy and practice: An overview. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 1990, 12, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banilower, E.R.; Smith, P.S.; Malzahn, K.A.; Plumley, C.L.; Gordon, E.M.; Hayes, M.L. Report of the 2018 NSSME+; Horizon Research, Inc.: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Reiser, B.J. What professional development strategies are needed for successful implementation of the Next Generation Science Standards. In Proceedings of the Invitational Research Symposium on Science Assessment; ETS Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Marín Blanco, A.; Bostedt, G.; Michel-Schertges, D.; Wüllner, S. Studying teacher shortages: Theoretical perspectives and methodological approaches. J. Pedagog. Res. 2023, 7, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluk, S. Addressing the Teacher Exodus via Mobile Pedagogies: Strengthening the Professional Capacity of Second-Career Preservice Teachers through Online Communities of Practice. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Lam, C.B.; Bruno, P. Is There a National Teacher Shortage? A Systematic Examination of Reports of Teacher Shortages in the United States; Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University: Providence, RI, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Will, M. What will teacher shortages look like in 2024 and beyond: A research weighs in. Education Week, 21 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, D.S.; Kraft, M.A.; Christian, A.; Candelaria, C.A. Teacher Shortages: A Unifying Framework for Understanding and Predicting Vacancies; Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University: Providence, RI, USA, 2022; pp. 22–684. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes, S.Q.; Bloom, M.A. The Intricacies of the STEM Teacher Shortage. Electron. J. Res. Sci. Math. Educ. 2023, 27, i–vii. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, R.; May, H. Recruitment, Retention and the Minority Teacher Shortage; CPRE Research Report #RR-69; Consortium for Policy Research in Education: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, R.; Perda, D. How high is teacher turnover and is it a problem. In Proceedings of the Consortium for Policy Research in Education; University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, P.; Loeb, S. Taking Stock: An Examination of Alternative Certification; Harvard Education Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marder, M. Teacher shortages and the decline of secondary teacher production. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of UTeach STEM Educators Association; UTeach Institute: Austin, TX, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stroupe, D.; Gotwals, A.; Christensen, J.; Wray, K.A. Becoming Ambitious: How a Practice-based Methods Course and “Macroteaching” Shaped Beginning Teachers’ Critical Pedagogical Discourses. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2022, 6, 683–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroupe, D.; Hammerness, K.; McDonald, S. Preparing Science Teachers through Practice-Based Teacher Education; Harvard Education Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Education, Office of Postsecondary Education. Meeting the Highly Qualified Teachers Challenge: The Secretary’s Annual Report on Teacher Quality; US Department of Education, Office of Postsecondary Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Education. Higher Education Act Title II Reporting System; Office of Postsecondary Education: 2019–2020.

- US Department of Education. National Teacher and Principal Survey (NTPS); Public School Teacher Data File; National Center for Education: 2020–2021.

- Darling-Hammond, L. Keeping good teachers: Why it matters, what leaders can do. Educ. Leadersh. 2003, 60, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Van Overschelde, J.P.; Wiggins, A.Y. Teacher Preparation Pathways: Differences in Program Selection and Teacher Retention. Action Teach. Educ. 2020, 42, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, J.S.; Tatto, M.T. Designs for initial teacher preparation programs: An international view. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2000, 33, 493–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Commission on Teaching & America’s Future. No Dream Denied: A Pledge to America’s Children; National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kee, A.N. Feelings of Preparedness Among Alternatively Certified Teachers. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 63, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S.; Stephenson, J. Does classroom management coursework influence pre-service teachers’ perceived preparedness or confidence? Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 28, 1131–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronfeldt, M. Links among Teacher Preparation, Retention, and Teaching Effectiveness. Evaluating and Improving Teacher Preparation Programs; National Academy of Education Committee on Evaluating and Improving Teacher Preparation Programs: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelis, K.J.; Wall, A.F.; Che, J. The Impact of Preservice Preparation and Early Career Support on Novice Teachers’ Career Intentions and Decisions. J. Teach. Educ. 2013, 64, 338–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldhaber, D.; Cowan, J. Excavating the Teacher Pipeline. J. Teach. Educ. 2014, 65, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dove, M.K. Teacher attrition: A critical American and International education issue. Delta Kappa Gamma Bull. 2004, 71, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, R.; Merrill, L.; May, H. What are the Effects of Teacher Education and Preparation on Beginning Teacher Attrition? Research Report [#RR-82]; Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, D.N.; Sass, T.R. Teacher training, teacher quality and student achievement. J. Public Econ. 2011, 95, 798–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M. Eight Questions on Teacher Preparation: What Does the Research Say? Education Commission of the States and the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Educational Research and Improvement: Denver, CO, USA, 2003.

- Schmidt, W.H.; Cogan, L.; Houang, R. The role of opportunity to learn in teacher preparation: An international context. J. Teach. Educ. 2011, 62, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.J.; Grossman, P.L.; Lankford, H.; Loeb, S.; Wyckoff, J. Teacher preparation and student achievement. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 2009, 31, 416–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, G.T.; Campbell, S.L.; Thompson, C.L.; Patriarca, L.A.; Luterbach, K.J.; Lys, D.B.; Covington, V.M. The Predictive Validity of Measures of Teacher Candidate Programs and Performance. J. Teach. Educ. 2013, 64, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, C. University-Based Teacher Preparation and Middle Grades Teacher Effectiveness. J. Teach. Educ. 2016, 68, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleickmann, T.; Richter, D.; Kunter, M.; Elsner, J.; Besser, M.; Krauss, S.; Baumert, J. Teachers’ content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge: The role of structural differences in teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 2013, 64, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronfeldt, M.; Matsko, K.K.; Nolan, H.G.; Reininger, M. Three Different Measures of Graduates’ Instructional Readiness and the Features of Preservice Preparation That Predict Them. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 72, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissim, Y.; Danial-Saad, A. The Resilient Teacher: Unveiling the Positive Impact of the Collaborative Practicum Model on Novice Teachers. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngs, P.; Qian, H. The influence of university courses and field experiences on Chinese elementary candidates’ mathematical knowledge for teaching. J. Teach. Educ. 2013, 64, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronfeldt, M.; Reininger, M. More or better student teaching? Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 28, 1091–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colley, C.; Windschitl, M. Rigor in elementary science students’ discourse: The role of responsiveness and supportive conditions for talk. Sci. Educ. 2016, 100, 1009–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.; Hagenah, S.; Kang, H.; Stroupe, D.; Braaten, M.; Colley, C.; Windschitl, M. Rigor and responsiveness in classroom activity. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2016, 118, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windschitl, M.; Thompson, J.; Braaten, M.; Stroupe, D. Proposing a core set of instructional practices and tools for teachers of science. Sci. Educ. 2012, 96, 878–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofianidis, A.; Kallery, M. An Insight into Teachers’ Classroom Practices: The Case of Secondary Education Science Teachers. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekkumru-Kisa, M.; Kisa, Z.; Hiester, H. Intellectual work required of students in science classrooms: Students’ opportunities to learn science. Res. Sci. Educ. 2021, 51, 1107–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boston, M.D.; Smith, M.S. Transforming secondary mathematics teaching: Increasing the cognitive demands of instructional tasks used in teachers’ classrooms. J. Res. Math. Educ. 2009, 40, 119–156. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, W. Academic work. Rev. Educ. Res. 1983, 53, 159–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebert, J.; Wearne, D. Instructional Tasks, Classroom Discourse, and Students’ Learning in Second-Grade Arithmetic. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1993, 30, 393–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.K.; Grover, B.W.; Henningsen, M. Building student capacity for mathematical thinking and reasoning: An analysis of mathematical tasks used in reform classrooms. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1996, 33, 455–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekkumru-Kisa, M.; Stein, M.K.; Schunn, C. A framework for analyzing cognitive demand and content-practices integration: Task analysis guide in science. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2015, 52, 659–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, M.; O’Shea, A. The role of task classification and design in curriculum making for preservice teachers of mathematics. Curric. J. 2020, 31, 436–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.K.; Smith, M.S.; Henningsen, M.A.; Silver, E.A. Implementing Standards-Based Math Instruction: A Casebook for Professional Development; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.-E.; Hwang, S.; Yeo, S. Preservice Teachers’ Task Identification and Modification Related to Cognitive Demand. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2023, 22, 911–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Windschitl, M.; Stroupe, D.; Thompson, J. Designing, launching, and implementing high quality learning opportunities for students that advance scientific thinking. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2016, 53, 1316–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munter, C.; Correnti, R. Examining Relations between Mathematics Teachers’ Instructional Vision and Knowledge and Change in Practice. Am. J. Educ. 2017, 123, 171–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boston, M. Assessing instructional quality in mathematics. Elem. Sch. J. 2012, 113, 76–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odden, T.O.B.; Russ, R.S. Defining sensemaking: Bringing clarity to a fragmented theoretical construct. Sci. Educ. 2019, 103, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windschitl, M.; Calabrese Barton, A. (Eds.) Rigor and Equity by Design: Locating a Set of Core Teaching Practices for the Science Education Community; American Educational Research Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 1099–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Tekkumru-Kisa, M.; Schunn, C.; Stein, M.K.; Reynolds, B. Change in thinking demands for students across the phases of a science task: An exploratory study. Res. Sci. Educ. 2019, 49, 859–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekkumru-Kisa, M.; Ackil-Okan, O.; Kisa, Z.; Southerland, S. Exploring science teaching in interaction at the instructional core. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2023, 60, 26–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Kim, J.W.; Mo, Y.; Walker, A.D. A review of professional learning community (PLC) instruments. J. Educ. Adm. 2022, 60, 262–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekkumru-Kisa, M.; Preston, C.; Kisa, Z.; Oz, E.; Morgan, J. Assessing instructional quality in science in the era of ambitious reforms: A pilot study. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2021, 58, 170–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Wei, R.C.; Andree, A.; Richardson, N.; Orphanos, S. Professional Learning in the Learning Profession: A Status Report on Teacher Development in the United States and Abroad; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Podolsky, A.; Kini, T.; Darling-Hammond, L. Does teaching experience increase teacher effectiveness? A review of US research. J. Prof. Cap. Community 2019, 4, 286–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L. President Obama and education: The possibility for dramatic improvements in teaching and learning. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2009, 79, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMonte, J. The Leaky Pipeline: Why Don’t New Teachers Return? 2016. Available online: https://www.air.org/resource/blog-post/leaky-pipeline-why-dont-new-teachers-teach (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Wright, D.S.; Balgopal, M.M.; Sample McMeeking, L.B.; Weinberg, A.E. Developing resilient K-12 STEM teachers. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2019, 21, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, R.; May, H.; Collins, G.; Fletcher, T. Trends in the Recruitment, Employment and Retention of Teachers from Under-Represented Racial-Ethnic Groups, 1987 to 2016; Chapter in The AERA Handbook of Research on Teachers of Color; American Educational Research Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, T. Teacher Shortage Is “Real and Growing, and Worse than We Thought. 2019. Available online: http://neatoday.org/2019/04/03/how-bad-is-the-teacher-shortage (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Boyd, D.; Grossman, P.; Lankford, H.; Loeb, S.; Wyckoff, J. Who Leaves? Teacher Attrition and Student Achievement; NBER Working Paper No. w14022; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Texas, E. Texas Educator Preparation Pathways Study: Developing and Sustaining the Texas Educator Workforce; University of Texas at Austin College of Education: Austin, TX, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pressley, T. Factors Contributing to Teacher Burnout During COVID-19. Educ. Res. 2021, 50, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, E.D.; Woo, A. Job-Related Stress Threatens the Teacher Supply: Key Findings from the 2021 State of the U.S. Teacher Survey; Rand Corperation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bang, M.; Warren, B.; Rosebery, A.S.; Medin, D. Desettling expectations in science education. Hum. Dev. 2013, 55, 302–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madkins, T.C.; Morton, K. Disrupting Anti-Blackness with Young Learners in STEM: Strategies for Elementary Science and Mathematics Teacher Education. Can. J. Sci. Math. Technol. Educ. 2021, 21, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Doyle, D. Justice-centered science pedagogy: A catalyst for academic achievement and social transformation. Sci. Educ. 2017, 101, 1034–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, R. Is There Really a Teacher Shortage? 2003. Available online: https://www.gse.upenn.edu/pdf/rmi/Shortage-RMI-09-2003.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Kennedy, M.M. Attribution Error and the Quest for Teacher Quality. Educ. Res. 2010, 39, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver-Thomas, D.; Darling-Hammond, L. The trouble with teacher turnover: How teacher attrition affects students and schools. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2019, 27, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, D.B.; Carletta, L.; Patzelt, S.P.; Ahmed, K. (Eds.) Making Sense of Science Teacher Retention: Teacher Embeddedness and Its Implications for New Teacher Support; American Association for the Advancement of Science: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; pp. 275–319. [Google Scholar]

- Kukla-Acevedo, S. Leavers, movers, and stayers: The role of workplace conditions in teacher mobility decisions. J. Educ. Res. 2009, 102, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Vasquez, C.; Carrasco, D.; Tapia-Ladino, M. Teacher mobility: What is it, how is it measured and what factors determine it? A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, D.B.; Patzelt, S.P.; Ahmed, K.M.; Carletta, L.; Gaynor, C.R. Portraying secondary science teacher retention with the person-position framework: An analysis of a state cohort of first-year science teachers. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2022, 59, 1235–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.; Sammons, P.; Gorgen, K. Successful School Leadership; Education Development Trust: Reading, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Travis, J.A.; Southerland, S.A.; Tekkumru-Kisa, M. Investigating Relationships between STEM Teacher Preparation, Instructional Quality, and Teacher Persistence. August 2017–July 2023, 1,399,709.00.

- Tekkumru-Kisa, M.; Stein, M.K.; Doyle, W. Theory and research on tasks revisited: Task as a context for students’ thinking in the era of ambitious reforms in mathematics and science. Educ. Res. 2020, 49, 606–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran-Smith, M. The Problem of Teacher Education. J. Teach. Educ. 2004, 55, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, S. What Keeps Teachers Going; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bürkner, P.-C. brms: An R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhemer, D.; Schellinger, J.M.; Southerland, S. Examining the Interaction Between Preparation Programs, Instructional Rigor, and Math and Science Teachers’ Persistence in Teaching. Presented at the 2023 AAAS Noyce Summit, Washington, DC, USA, 26–28 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sutcher, L.; Darling-Hammond, L.; Carver-Thomas, D. Understanding teacher shortages: An analysis of teacher supply and demand in the United States. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2019, 27, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Program Location | Teachers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reform-Based Math Standards (i.e., Common Core) | Reform-Based Science Standards (i.e., NGSS) | Math | Science | Total | |

| East Coast | Adapted | No | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Intermountain West | Yes | Adapted | 7 | 10 | 17 |

| Northeast | Yes | Adapted | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Southeast | Adapted | Adapted | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| West Coast | Yes | Yes | 4 | 11 | 15 * |

| Total: 46 | |||||

| Rubric and Data | Category of Rigor | Math Descriptor | Science Descriptor |

|---|---|---|---|

| R1 Academic Rigor in Task Potential (Task) | High | Problem Solving: The task has the potential to engage students in exploring and understanding the nature of mathematical concepts, procedures, and/or relationships (that is, using complex, non-algorithmic thinking), and students must provide their reasoning. The task suggests no approach or pathway; thus, it requires wrestling with ambiguity for its resolution. | Figuring Out: The task has the potential to engage students in sensible versions of the actual intellectual work of science—requiring students to develop explanations through the use of three dimensions of science (disciplinary core ideas, crosscutting concepts, and scientific practices). The task requires wrestling with ambiguity to create this explanation. |

| Moderate | Apply Procedures: The task has the potential to engage students in complex thinking (such as finding relations, analyzing information, and generalizing to a broader idea), but the task does not ask for students’ reasoning. The emphasis is on following a prescribed procedure for sensemaking but without an explanation of reasoning. | Learning About: The task has the potential to engage students in complex thinking and high-level cognitive processes (such as finding relations, analyzing information, and generalizing to a broader idea), but science content or scientific practices are forefronted. The emphasis is on learning about science content or practices. | |

| Low | Rote/Procedural: The potential of the task is limited: either to engaging students in using a specified procedure, or its use is evident or engages students in reproducing memorized information (facts, rules, formulas, or definitions.) | Rote/Procedural: The potential of the task is limited: either to engaging students in using a specified procedure, or its use is evident or engages students in reproducing memorized information (facts, rules, formulas, or definitions). | |

| Absent | Absent: The task requires no mathematical activity. | Absent: The task requires no scientific activity. |

| Rubric and Data | Category of Rigor | Math Descriptor | Science Descriptor |

|---|---|---|---|

| R2 Academic Rigor of Task Implementation (Student Work) | High | Problem Solving: Students’ work indicated that students were engaged in problem solving, as students were engaged in exploring and understanding the nature of mathematical concepts, procedures, and/or relationships (that is, using complex, non-algorithmic thinking), and explained their reasoning. Variation in students’ problem solving suggested that the procedures were not predetermined. | Figuring Out: Students’ work indicated that students were engaged in sensible versions of the actual intellectual work of science, and students drew on explanations using three dimensions of science (disciplinary core ideas, crosscutting concepts, and scientific practices) to develop explanations. Variations in students’ work indicated that students wrestled with ambiguity when creating this explanation. |

| Moderate | Apply Procedures: Students’ work indicated that students were engaged in problem solving, but students did not explain their reasoning. Uniformity of students’ work suggests that the procedures were prescribed. | Learning About: Students’ work indicated engagement in complex thinking, primarily focused on either science content or practices and an emphasis on knowing and understanding content or practices. | |

| Low | Rote/Procedural: Students’ work indicated that they engaged with the task at a procedural level, applying prescribed procedures to provide the correct answer, showing the steps, or students reproduced memorized information (facts, rules, formulas, or definitions). | Rote/Procedural: Students’ work indicated engagement in procedures that led them to complete the task without knowing (or needing to know) why and how the script led to that answer and indicated students’ use of skills/mechanics associated with the practices, or students reproduced memorized information (facts, rules, formulas, or definitions). | |

| Absent | Absent: Students’ work provided no evidence of mathematical activity. | Absent: Students’ work provided no evidence of scientific activity |

| Rubric and Data | Category of Rigor | Math Descriptor | Science Descriptor |

|---|---|---|---|

| R3 Academic Rigor of Teacher Expectations (Cover Sheet) | High | Problem Solving: The majority of the teachers’ expectations were for students to engage with the high-level demands of the task, such as using complex thinking and/or exploring, and understanding mathematical concepts, procedures, and/or relationships. | Figuring Out: The majority of the teachers’ expectations were for students to engage in sensemaking, using the SEP, DCI, and CCC together in the service of explaining (i.e., figuring out) a phenomenon (i.e., productive engagement in practices was indicated in the teachers’ expectations). |

| Moderate | Apply Procedures: The teacher expected students to engage in complex mathematical thinking, but scaffolds were provided that lessened the demand on student thinking. | Learning About: The majority of teacher expectations were for students to engage in complex thinking, but either science content or scientific practices were forefronted. The emphasis was on learning about content or practices. | |

| Low | Rote/Procedural: Teacher expectations focused on student learning but not on complex thinking (e.g., expecting the use of a specific problem-solving strategy, and expecting short answers based on memorized facts, rules, or formulas), or teacher expectations were not focused on math (i.e., following directions, neat work, and student effort). | Rote/Procedural: Teacher expectations focused on student learning, but not on complex thinking (e.g., correct use of the prescribed procedure), or teacher expectations were not focused on science activity (i.e., following directions, neat work, and student effort). | |

| Absent | Absent: No teacher expectations for student work were found. | Absent: No teacher expectations for student work were found. |

| Employment Status | Description |

|---|---|

| Active | Current K-12 teachers |

| Enhancers | Current K-12 teachers who have taken on additional responsibilities that enhance their school or district (e.g., PLC leader, curriculum designer, mentor teacher, etc.) |

| Advancers | Former K-12 teachers who are employed in education-related positions where teacher certification has value (e.g., administration, higher education, or informal education) |

| Attritted | Former K-12 teachers who are no longer employed in the educational profession |

| Program Location | Degree Level | Requirements | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| East Coast * | Undergraduate |

| Rigorous instruction |

| Intermountain West | Undergraduate |

| Culturally relevant pedagogy/Culture of care |

| Northeast | Master of Arts in Teaching (MAT) |

| Culturally relevant pedagogy |

| Southeast | Post-baccalaureate |

| None listed |

| West Coast | Post-baccalaureate |

| Culturally relevant pedagogy/Social justice |

| Program Location | Degree Level | Field Hours (Early Field and Student Teaching) | Education Course Hours | Math and Science Content Course Hours * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF | ST | ||||

| East Coast * | Undergraduate | 150 | 465 | 42 | 48 |

| Intermountain West | Undergraduate | 160 | 640 | 33 | 90 |

| Northeast | Postgraduate | 90 | 450 | 36 | Math and science degree required for admission |

| Southeast | Postgraduate | 200 | 0 | 39 | 23 h of math and science recommended for admission |

| West Coast | Postgraduate | 160 | 640 | 37 | Math and science degree required for admission |

| Preparation Program | Instructional Quality (Rigor Categories) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Degree Level | R1-Potential | R2-Implementation | R3-Expectations | |||

| Mode | Range | Mode | Range | Mode | Range | ||

| Math | |||||||

| East Coast * | Undergraduate | Low | Low–High | Low | Low–High | Low | Absent–High |

| Intermountain West | Undergraduate | Low | Low–High | Low | Low–High | Low | Absent–High |

| Northeast | Postgraduate | Low | Low–High | Low | Low–High | Low | Low–High |

| Southeast | Postgraduate | Low | Low–Moderate | Low | Low–Moderate | Low | Low–Moderate |

| West Coast | Postgraduate | High | Low–High | Low | Low–High | Low | Low–High |

| Science | |||||||

| Intermountain West | Undergraduate | Moderate | Absent–High | Low | Absent–High | Moderate | Absent–High |

| Northeast | Postgraduate | Moderate | Low–High | Moderate | Low–Moderate | Moderate | Low–High |

| Southeast | Postgraduate | Moderate | Low–High | Low | Low–High | Moderate | Low–Moderate |

| West Coast | Postgraduate | Moderate | Low–High | Low | Low–High | Moderate | Low–High |

| Teacher Preparation Program | Teacher Persistence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active | Enhancers | Advancers | Attritted | |

| Undergraduate | ||||

| Intermountain West n = 17 | ~71% (12) | ~6% (1) | ~12% (2) | ~12% (2) |

| East Coast * n = 5 | 20% (1) | 0% (0) | 20% (1) | 60% (3) |

| Undergraduate Total: n = 22 | 59% (13) | 5% (1) | 14% (3) | 23% (5) |

| Postgraduate | ||||

| West Coast ** n = 6 | ~25% (1) ** | 50% (4) ** | 25% (1) ** | 0% (0) |

| Northeast n = 6 | 100% (6) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Southeast n = 3 | 100% (3) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Graduate Total: n = 15 | ~67% (10) | ~27% (4) | ~7% (1) | 0% (0) |

| Total: n = 37 | ~62% (23) | ~14% (5) | ~11% (4) | ~14% (5) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rhemer, D.M.; Rogers, W.; Southerland, S.A. Examining the Influence of Secondary Math and Science Teacher Preparation Programs on Graduates’ Instructional Quality and Persistence in Teaching. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 506. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050506

Rhemer DM, Rogers W, Southerland SA. Examining the Influence of Secondary Math and Science Teacher Preparation Programs on Graduates’ Instructional Quality and Persistence in Teaching. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(5):506. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050506

Chicago/Turabian StyleRhemer, Danielle Marie, Will Rogers, and Sherry Ann Southerland. 2024. "Examining the Influence of Secondary Math and Science Teacher Preparation Programs on Graduates’ Instructional Quality and Persistence in Teaching" Education Sciences 14, no. 5: 506. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050506

APA StyleRhemer, D. M., Rogers, W., & Southerland, S. A. (2024). Examining the Influence of Secondary Math and Science Teacher Preparation Programs on Graduates’ Instructional Quality and Persistence in Teaching. Education Sciences, 14(5), 506. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050506