Bridging Theory and Practice: Using Goal Systems to Spark Professional Dialogue and Develop Personal Theories

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

- A better and explicit understanding of the student teacher, with respect to their own goal–means relations (level 1)?

- A more thorough awareness of the theoretical notions that may explain or underly these goal–means relations (level 2)?

- A more transformative use of theory in professional dialogues about these goal–means relations to foresee and hypothesize potential new practices (level 3)?

3. Methods

3.1. Context and Cases

3.2. Data Collection

- GSRs and mentor notes: the GSRs made by the student teachers were collected and digitalized as well as the mentors’ notes about the GSRs of their students in preparation for their mentoring conversations;

- Video recordings and transcripts: the mentor–student teacher conversations were videorecorded (case 1: 19′; case2: 16′; case3: 15′) and all relevant parts of the recordings were transcribed;

- Reflections of student teachers: the student teachers were asked to reflect on creating the GSR and on the mentoring conversations. Written reflections of ST2 and ST3 were collected in the week after the mentoring conversation took place (digital, Google Form). They were asked to score three short statements on the perceived usefulness of the GSR in the mentoring situation (1–5, certainly not–definitely) and to explain their scores. ST1 reflected briefly with her mentor on the mentor conversation at the end of the conversation in response to an open question (audio).

- Reflections of mentors: M2’s written reflection was collected the week after the conversation took place (digital, Word doc). She was asked to score 3 short statements on the usefulness of the GSR tool (1–4, certainly not–definitely) and to explain her scores. M1 and M3 reflected on the conversation and their mentoring practices when they analyzed the videotapes of each other’s conversation. They discussed this with the researchers (author 1, 3 and 4), who made notes (researchers notes). M3 additionally made notes in a log he kept. In the analysis, we examined how the mentors perceived the GSR as either facilitating or hindering the reflection process of their student teachers.

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

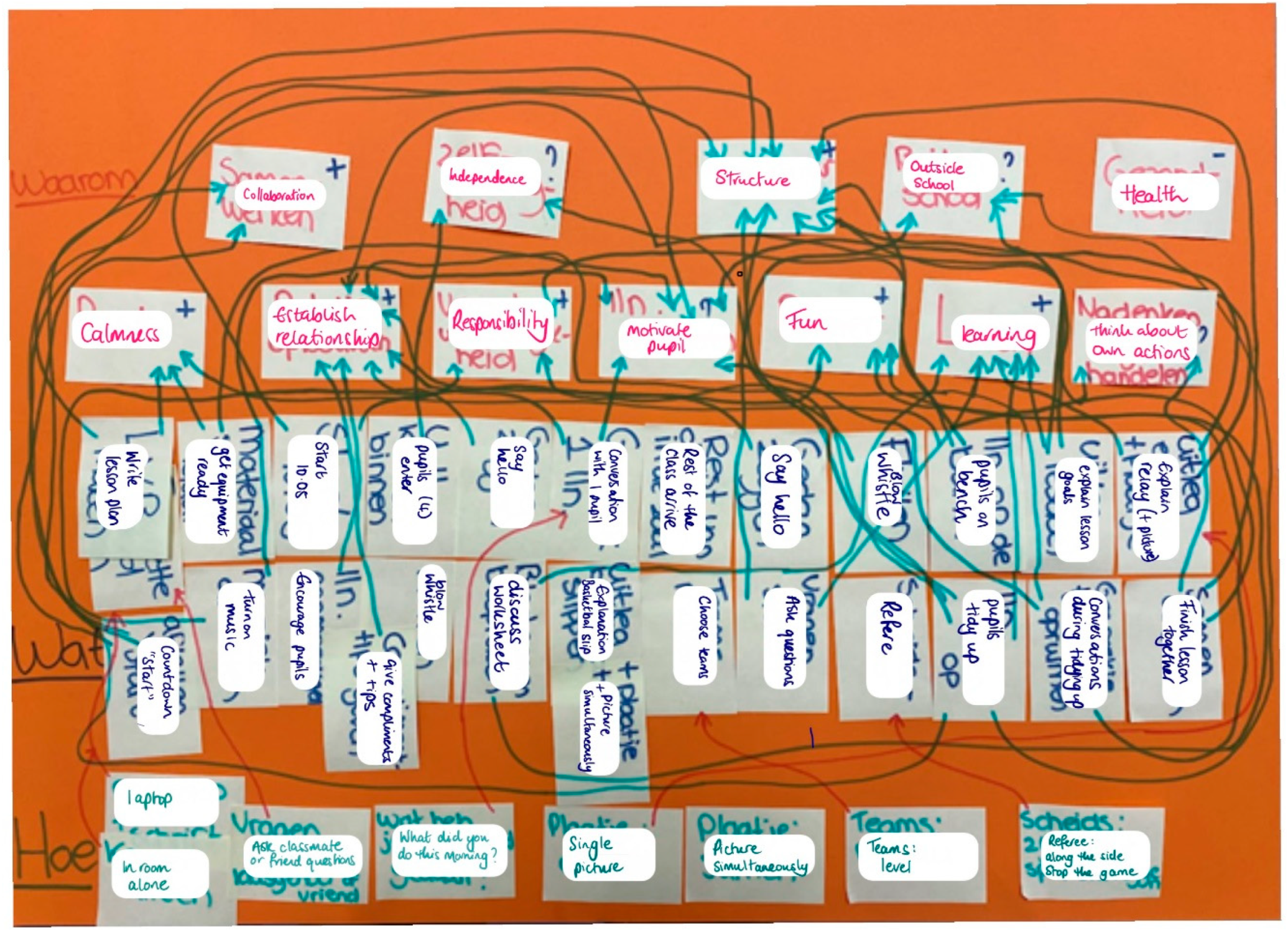

4.1. Case 1: How the Urge to ‘Control’ Shapes Practice (Level 2)

- M1:

- Well, I’ve studied it [points at GSR] a bit and formulated some questions. What I actually liked is that you immediately dig deep.

- ST1:

- Really? (surprised)

- M1:

- Yes, quite. Well, you might be able to go even deeper, but for a first-year, youranalysis is quite in-depth.

- ST1:

- Okay (a bit bewildered), I actually found it quite superficial.

- M1:

- Why did you find it superficial?

- ST1:

- Because I really have the feeling that I can dig deeper into the material. But, ofcourse, I haven’t covered everything yet at the institute.

- M1:

- Do you find that challenging?

- ST1:

- What?

- M1:

- Find it challenging to go that extra layer deeper.

- ST1:

- Yes.

- M1:

- Well, I think, [reads aloud from the GSR] ‘it motivates me’; ‘it motivates the stdents’; ‘building a relationship with the students’, that you already go quite in-depthinto why you do it this way. Of course, you can still think about it further.

- ST1:

- Yes.

- M1:

- I notice that you really want to do everything perfectly. Do you recognize thatyourself?

- ST1:

- I am extremely? perfectionistic, yes [laughs] and very strict with myself.

- M1:

- So, what I hear as well, you mentioned being perfectionistic, [reads aloud from the GSR] ‘keeping street culture out’, and what I also see is [reads aloud] ‘what is going well, support, structure’. I see these things a lot. Apparently, structure and control are important to you. Do you also know why this is so important for you?

- ST1:

- For me?

- M1:

- For you, yes

- ST1:

- Um, I don’t know, I think it has a bit to do with myself. I am really a control freak in everything I do.

- M1:

- smiles

- ST1:

- I just really want to have control because, if I do not have control, then…. I was…..let’s say, hurt quite a bit outside of school, things in the past.

- M1:

- Yes

- ST1:

- So I am afraid—yeah, they won’t hurt me here, I think—but if I just have control, then I do what I do, and no one can hurt me.

- M1:

- At least you’ve done what is right?

- ST1:

- Yes, yes

- M1:

- Because you’re afraid of being hurt

- ST1:

- Yes, I cannot deal with that very well [laughs shyly]

- M1:

- Yes, but it’s good that you know that about yourself.

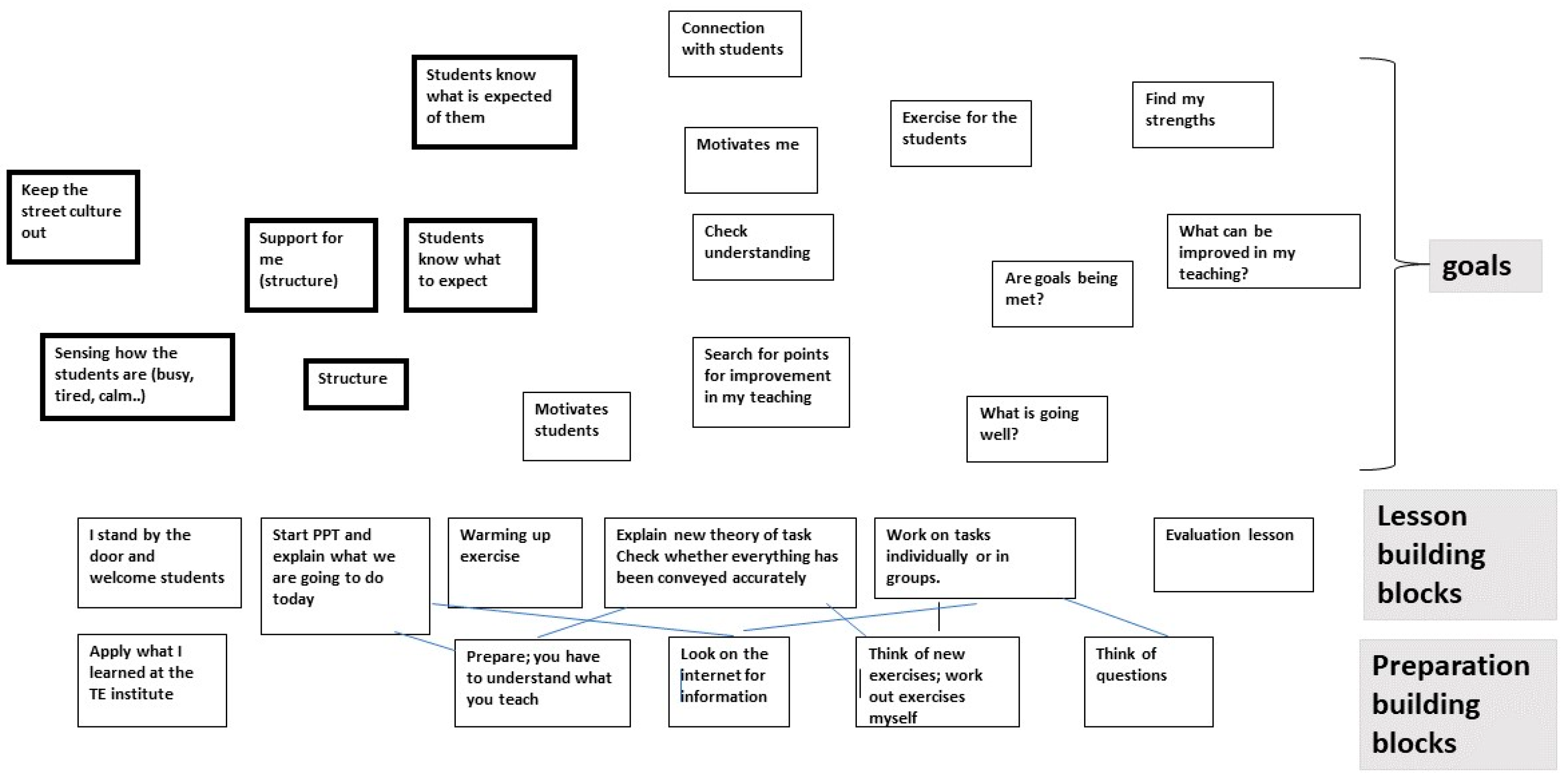

4.2. Case 2 about the Importance of Explicating Implicit Routines (Level 1) and Underlying Beliefs (Level 20)

- M2:

- I find it so nice that this comes out. Because what was on my mind when I saw the picture of your lesson, and now I’m going to grab mine [grabs GSR]. For example, I see here in your GSR ‘seeing every student’ under relationship, and then I think, hey, I think you do that not only by standing at the door and giving students time to settle, but you do that much more often in your lesson.

- ST2:

- Yes.

- M2:

- But I don’t see it [in the GSR picture].

- ST2:

- No, no. It happens naturally.

- M2:

- So basically, you’re saying it happens naturally.

- ST2:

- It’s almost like stating the obvious, that you see a student.

- M2:

- Yes, for you it’s stating the obvious. But someone who sees this [points at GSR] and doesn’t know you, what might they think then?

- ST2:

- Yes, yes. They might think that everything is very [gestures delimited parts] this is it.

- M2:

- Yes, I think someone who doesn’t know you might think, oh, does she only think to work on the relationship here, while I’ve seen your lessons and I know that you work on the relationship at many moments. So basically, I would like to ask you, could you consider on which other moments you also work on the relationship, and could you make those connections? And I’ve noticed that with several post-its, that you work on it at many more moments but that you’re not consciously aware of it anymore

- ST2:

- Yes, I even found that in mentoring interns, where with some you’d say, ‘yes, they have that so naturally in their interactions with students.’ And then with others, I sometimes found it quite difficult to offer guidance like, ‘try it this way or that way.’

- M2:

- And how important is it for an intern, in this case, you being my intern, how important is it for someone who is learning to be aware of that?

- ST2:

- Yes, um, it is important that you also know it.

- Next,

- similar to case 1, the specific ‘why is that important to you’ inquiry in the first utterance of M2 prompts a reflective professional dialogue that helps ST2 connect seeing every student to creating a safe environment for learning.

- M2:

- And then I become curious. From which standpoint do you set certain goals? For example, ‘seeing every student’, now that comes from your belief that safety is important. But there’s something there again, Why is that important?

- ST2:

- Because I think that if you feel safe, that’s when you start to learn. Because that’s how it works for me too.

- M2:

- Okay.

- ST2:

- And of course, I’m new here in the team. I feel very safe here, So then I can also move forward. If that’s not the case, I think it’s very unpleasant.

- M2:

- So you’re saying safety is important for students to learn. You’re also saying safety is important for myself to work well.

- ST2:

- Yes, yes.

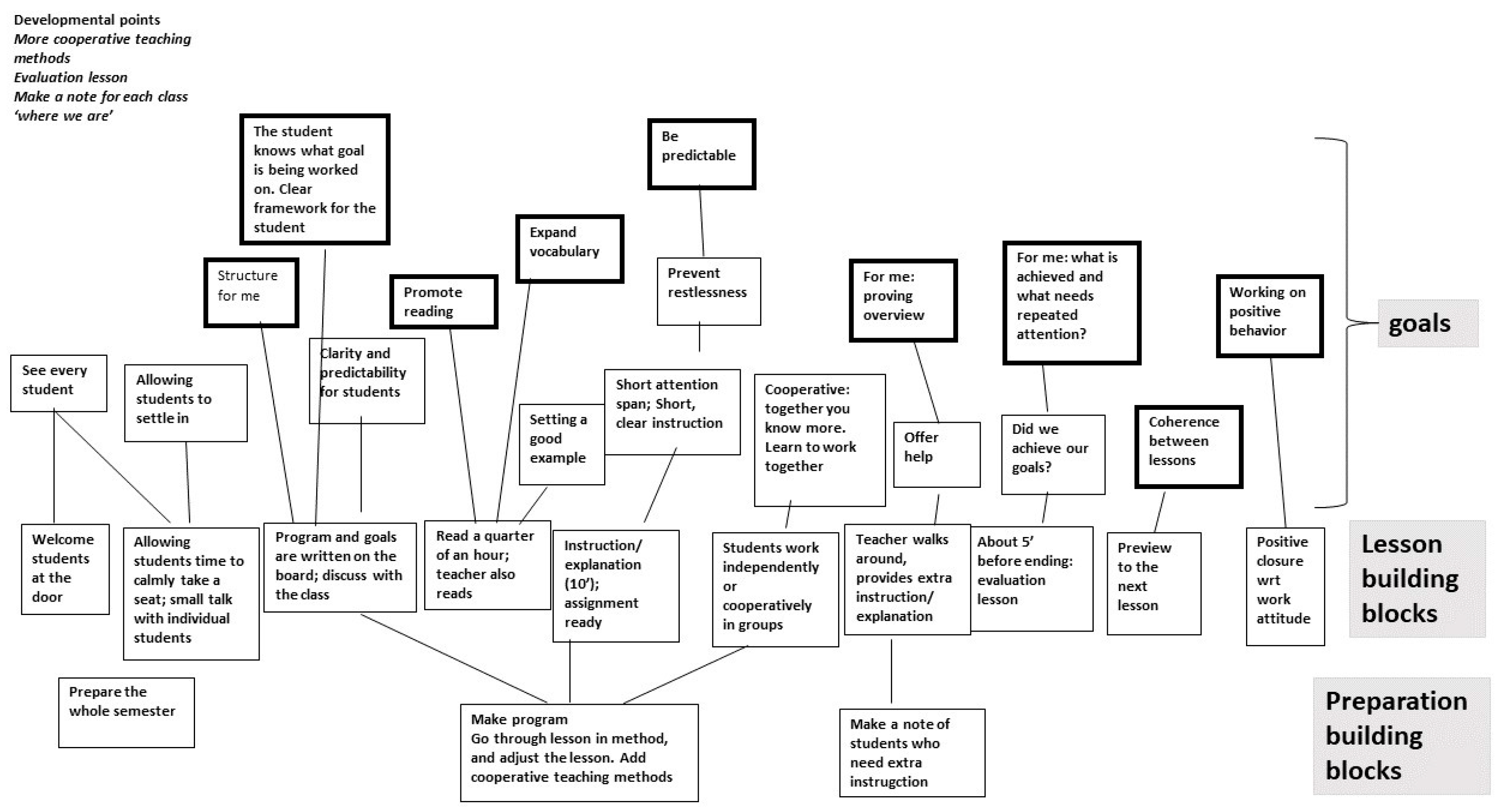

4.3. Case 3 about Central Beliefs and Implicit Higher Identity Goals

- M3:

- My first question is how did you like it, making your GSR?

- ST3:

- Eeh, it makes you aware of what you do, or do the most. What you consider important. All those lines and a lot of lines going to one thing. And less [lines] to another thing. Well, the many lines that is what I evidently find important. Yeah, I found that out through this.

- M3:

- Without delving too deeply into it [pointing to GSR], based on what you see here now. What has stuck with you, like, oh yes, that really stayed with me?

- ST3:

- Yes, well, actually what I find really important. If I may mention that... Structure, because there are a lot of threads leading to that. Apparently, I incorporate that a lot in my lessons. Well, I didn’t know that. Or perhaps unconsciously, yes, but.

- M3:

- You have now made that more conscious for yourself

- ST3:

- Yes

- M3:

- And did this already lead to any changes?

- ST3:

- Yes, you also handle it more consciously, like, ‘Oh, there I go again.’ Like, see I am putting them [the students] back on the bench again.

- M3:

- Yes, it also stood out to me when I looked at it. My question is, why is structure important to you?

- ST3:

- Uhm, I think it brings more calm, I guess. Um, yes, structure ensures that students know what to expect. Yes, I think building upon the lesson from there. Yes, you obviously start with it at the beginning of the school year, like ‘this is what happens in the lesson’.

- M3:

- Yes, and that building upon continues when there’s a good structure in

- ST3:

- Yes

- M3:

- Can we then say that structure is a kind of tool for you?

- ST3:

- Yes

- M3:

- So, that’s actually quite an insightful observation. So, that structure is actually a ‘prerequisite for teaching for me’

- ST3:

- Yes exactly

- [a similar dialogue around ST3’s central goal ‘reflection’ unfolds]

- M3:

- You indicate you don’t have much idea about the pupils outside school.

- ST3:

- Yes that’s true

- M3:

- You have placed it in your GSR as important. Can you describe the ideal situation outside school? And the second question: wat is your role in this?

- ST3:

- What I see as an idea situation, is that they (the pupils) do something in the lesson and then they go and do it with their friends when they leave school. Actually, especially that, that they take something from the PE lesson which they can also do at home or with friends. What was your second question?

- M3:

- What is your role in this?

- ST3:

- mm I don’t really know, that’s why I’ve drawn a question mark. How can I, really…. Show them that they can do it (at home or with friends).

- M3:

- Yes, but if I refer back to my first question, why is it so important that the pupils take something from your lesson which they can do in their own time?

- ST3:

- eerrrr that’s about exercising for your whole life.

- M3:

- Really? Is that something important to you?

- ST3:

- Yes, yes. It would be nice if they could do something in the lesson and think oh that was really cool. And then you speak to them later and they say oh yeah that’s what we did in that lesson

- M3:

- And what more does it mean to you exercising for life, what do you hope to achieve with it?

- ST3:

- Yeah that they move and exercise!

- M3:

- Yes, and why?

- ST3:

- Because its good for you, it’s healthy!

- M3:

- Yes, yes so you want to create healthy people in the world.

- ST3:

- Yes

- M3:

- And apart from being healthy, are there any other things? Apart from health?

- ST3:

- Well, yes, its also about how you treat each other, taken others into consideration. How you deal with winning and losing.

- M3:

- Yes exactly. All those skills, you hope because you teach that during the lessons, that they take that away from the lessons, because it’s good or them.

- ST3:

- Yes, and that’s its not just in the PE lesson.

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buitink, J. What and How Do Student Teachers Learn during School-Based Teacher Education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2009, 25, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijaard, D.; Verloop, N. Assessing Teachers’ Practical Knowledge. Stud. Educ. Eval. 1996, 22, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaranen, K.; Pitkaniemi, H.; Stenberg, K.; Karlsson, L. An idealistic view of teaching: Teacher students’ personal practical theories. J. Educ. Teach. 2016, 42, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, D. Bridging the gap between research and practice. Camb. J. Educ. 2005, 35, 357–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Reeve, J.; Deci, E.L. Engaging students in learning activities: It is not autonomy support or structure but autonomy support and structure. J. Educ. Psych. 2010, 102, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Sierens, E.; Goossens, L.; Soenens, B.; Dochy, F.; Mouratidis, A.; Aelterman, N.; Haerens, L.; Beyers, W. Identifying configurations of perceived teacher autonomy support and structure: Associations with self-regulated learning, motivation and problem behavior. Learn. Instruct. 2012, 22, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjölie, E. The role of theory in teacher education: Reconsidered from a student teacher perspective. J. Curr. Stud. 2014, 46, 729–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korthagen, F.; Kessels, J. Linking theory and practice: Changing the pedagogy of teacher education. Edu. Res. 1999, 28, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pols, W. Wijsheid van de praktijk: Over het stille weten in de onderwijspraktijk. Practical wisdom: About tacit knowledge in educational practice. Tijd. Voor Lerarenop. 2009, 30, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, M.; Kazemi, E.; Schneider Kavanagh, S. Core Practices and Pedagogies of Teacher Education A Call for a Common Language and Collective Activity. J. Teach. Educ. 2013, 64, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. Positive emotions. In Handbook of Positive Psychology, 2nd ed.; Snyder, C.R., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 120–134. [Google Scholar]

- Isen, A.M. Positive affect, cognitive processes, and social behavior. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 47, 1206–1217. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, F.; de Hullu, E.; Tigelaar, D. Positive experiences as input for reflection by student teachers. Teach. Teach. 2008, 14, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L. Constructing 21st-century teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 2006, 57, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P.; Hammerness, K.; McDonald, M. Redefining teaching, re-imagining teacher education. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2009, 15, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbroek, H.B.; Kaal, A.A.; Dönszelmann, S. A motivational perspective on learning core practices. The case of a Dutch Teaching Education program. In Core Practices in Teacher Education: A Global Perspective; Grossmann, P., Fraefel, U., Eds.; Harvard Educational Publishing Group: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Westbroek, H.B.; Janssen, F.; Doyle, W. Perfectly Reasonable in a Practical World: Understanding Chemistry Teacher Responses to a Change Proposal. Res. Sci. Educ. 2017, 47, 1403–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, F.J.J.M.; Westbroek, H.B.; Doyle, W.; van Driel, J.H. How to Make Innovations Practical. Teach. Col. Rec. 2013, 115, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, F.; Westbroek, H.B.; Doyle, W. Practicality studies: How to move from what works in principle to what works in practice. J. Learn. Sci. 2015, 24, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieringa, N.; Janssen, F.J.J.M.; Van Driel, J.H. Het Gebruik van doelsystemen om de interpretatie en implementatie van concept-contextonderwijs door biologiedocenten te begrijpen [using goal systems for understanding how biology teachers interpret and implement context-based biology education. Ped. Stud. 2013, 90, 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Westbroek, H.B.; Jongejan, W.; Kaal, A.A.; de Vries, B. Research Literacy in Initial Teacher Education: The Development of Personal Theories. In Developing Teachers’ Research Literacy: International Perspectives; Boyd, P., Szplit, A., Zbróg, Z., Eds.; Libron: Kraków, Poland, 2021; pp. 113–137. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, F.J.J.M.; Grossman, P.; Westbroek, H.B. Facilitating Decomposition and Recomposition in Practice-Based Teacher Education: The Power of Modularity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 51, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbroek, H.; de Vries, B.; Jongejan, W.; Kaal, A.; Pauw, I. Opleiden voor de toekomst: Hoe praten over onderzoek professionele ruimte creëert [Educating for the future: How critical dialogue about educational research enhances student teachers’ professional space]. Tijd. Voor Lerarenopleid. 2018, 39, 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Westbroek, H.B.; Kaal, A.A. Het Maken van een Doelsysteem Representatie als Basis Voor Reflectie [Creating a Goal System Representation as a Starting Point for Reflection]. Paper Presented at the Annual Onderwijs Research Dagen, Antwerpen, Belgium, 28–30 June 2017. Available online: https://www.uantwerpen.be/nl/overuantwerpen/faculteiten/antwerp-school-of-education/projecten-en-studiedagen/onderwijs-research-d/ (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Clarke, A.; Triggs, V.; Nielsen, W. Cooperating teacher participation in teacher education: A review of the literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 2014, 84, 163–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffield, S. Safety net or free fall: The impact of cooperating teachers. Teach. Devel. 2006, 10, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeichner, K. Rethinking the connections between campus courses and field experiences in college-and university-based teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 2010, 61, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ginkel, G.; Van Drie, J.; Verloop, N. Mentor teachers’ views of their mentees. Ment. Tut. Partner. Learn. 2018, 16, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orland-Barak, L.; Wang, J. Teacher mentoring in service of preservice teachers’ learning to teach: Conceptual bases, characteristics, and challenges for teacher education reform. J. Teach. Educ. 2021, 72, 86e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Odell, S.J. Mentored learning to teach according to standards based reform: A critical review. Rev. Educ. Res. 2002, 72, 481–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, W.; Weisling, N. Challenges and complexities of developing mentors’ practice: Insights from new mentors. Int. J. Mentor. Coach. Educ. 2018, 7, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, A. Professional self-understanding as expertise in teaching about teaching. Teach. Teach. 2009, 15, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, F.; Westbroek, H.B.; Borko, H. The indispensable role of the goal construct in understanding and improving teaching practice. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S. Self-awareness. In Handbook of Self and Identity; Leary, M.R., Tangney, J.P., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 50–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wieringa, N.; Janssen, F.J.J.M.; Van Driel, J.H. Biology teachers designing context-based lessons for their classroom practice—The importance of rules-of-thumb. Inter. J. Sci. Educ. 2011, 34, 2437–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M.M. Attribution Error and the Quest for Teacher Quality. Educ. Res. 2010, 39, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. The Sciences of the Artificial, 3rd ed.; MIT Press: Cambrige, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; Salmon, H., Perry, K., Koscielak, K., Barett, L., Hutchinson, A., Eds.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Czerniawski, G.; Guberman, A.; MacPhail, A.; Vanassche, E. Identifying school-based teacher educators’ professional learning needs: An international survey. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.; Sumara, D.J. Cognition, complexity, and teacher education. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1997, 67, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessen, T.; Abma, T.; Widdershoen, G.; Van der Vleuten, C. Contemporary epistemological research in education. Theory Psych. 2009, 18, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice. Learning, Meaning and Identity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Akkerman, S.F.; Meijer, P.C. A dialogical approach to conceptualizing teacher identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2011, 27, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korthagen, F.A.J. Een softe benadering van reflectie helpt niet [a soft approach to reflection does not help]. Tijd. Voor Lerarenop. 2014, 35, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C. Double-loop learning: A concept and process for leadership educators. J. Lead. Educ. 2002, 1, 68–71. [Google Scholar]

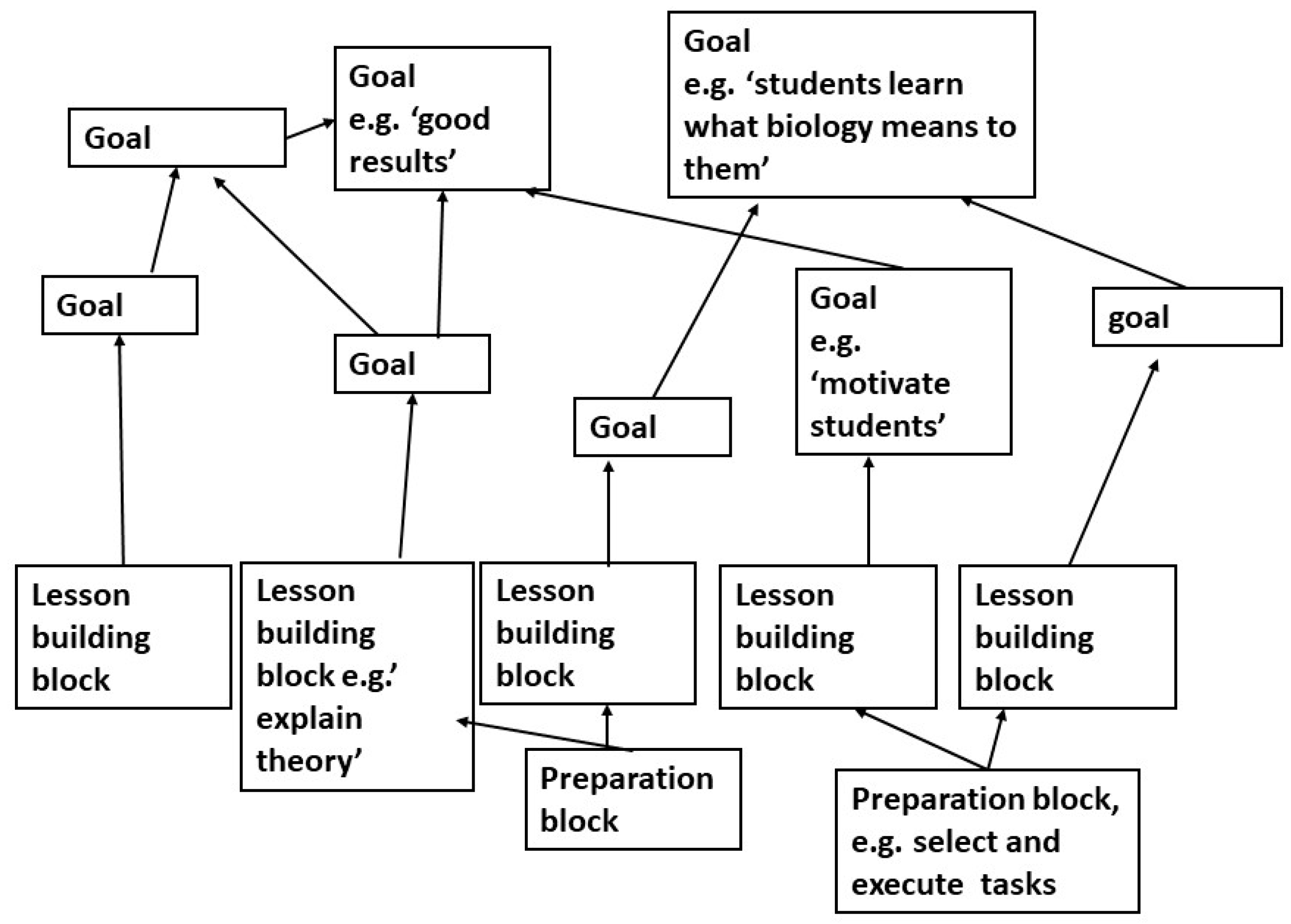

| Creating the WHAT row (‘recreating the lesson scenario’) | |

| Step 1 | Think of a typical lesson that is representative of your teaching approach |

| Step 2 | What do you first in your lesson? What do you do after that? And after that? Divide the lesson into activities (building blocks) and put them into chronological order. Write each activity on a separate piece of paper to make a row. |

| Creating the HOW row (‘looking at the preparation’) | |

| Step 1 | How do you prepare for each activity? Write each action on a separate piece of paper and create a new row underneath. |

| Step 2 | Connect each action (how) with an activity (what) or activities by drawing a line between them. |

| Creating the WHY row (‘looking at the underlying goals’) | |

| Step 1 | What do you hope to achieve with each activity? Why do you do it like that? Write down each goal you identify on a new piece of paper. Create a new row above the activities. |

| Step 2 | Connect these goals by drawing lines between the relevant action (how) or activity (what). |

| Step 3 | Look at your goals. Why do you find these important? Write down each reason or higher goal on a separate piece of paper and create a top row of higher order goals |

| Step 4 | Connect the higher order goals with the other relevant goals, building blocks or preparation by drawing lines between them. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Westbroek, H.; de Vries, B.; Kaal, A.; McDonnell, M. Bridging Theory and Practice: Using Goal Systems to Spark Professional Dialogue and Develop Personal Theories. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050458

Westbroek H, de Vries B, Kaal A, McDonnell M. Bridging Theory and Practice: Using Goal Systems to Spark Professional Dialogue and Develop Personal Theories. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(5):458. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050458

Chicago/Turabian StyleWestbroek, Hanna, Bregje de Vries, Anna Kaal, and Michelle McDonnell. 2024. "Bridging Theory and Practice: Using Goal Systems to Spark Professional Dialogue and Develop Personal Theories" Education Sciences 14, no. 5: 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050458

APA StyleWestbroek, H., de Vries, B., Kaal, A., & McDonnell, M. (2024). Bridging Theory and Practice: Using Goal Systems to Spark Professional Dialogue and Develop Personal Theories. Education Sciences, 14(5), 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050458