Abstract

Simulation-based learning experiences (SBLEs) are effective for teaching healthcare students clinical and communication skills. The current study assessed self-perceived clinical and communication confidence among dietetics students completing a series of four SBLEs (3 group, 1 individual) across nine months. Dietetics students were recruited in February 2023 prior to their first SBLE. Simultaneously through the academic year, students completed clinical and communication courses. Students were invited to complete an online, anonymous self-reported survey regarding confidence with nutrition care and communication prior to their first SBLE (Time 1), prior to their third SBLE (Time 2), and following their final SBLE (Time 3). The survey measured healthcare work experience and self-perceived confidence. Student confidence increased among 30 of the 38 indicators (p < 0.05). At Time 2 (following two group SBLEs), those with healthcare experience had higher confidence among 12 of the 39 items (p < 0.05). At Time 3 (following four simulation experiences) those with healthcare experience had higher confidence among just four of the 39 total items (p < 0.05). Cohort increases in confidence suggest that SBLEs, along with dietetics coursework, were critical in increasing confidence and students’ perceived ability to carry-out entry-level tasks of a dietitian. While student confidence increased across the cohort, SBLEs were particularly beneficial in leveling confidence between those with prior clinical experience and those without.

1. Introduction

Didactic programs in dietetics (DPDs) are the academic coursework programs that prepare graduates for entry into supervised practice or advanced degree programs. Together, experiences derived from the supervised practice, DPD programs, and/or graduate education programs prepare graduates as entry-level registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs) in the food and nutrition-related workforce. Before sitting for the credentialing exam to earn the RDN credential, students must complete required knowledge base (KRDNs) that can be gained during the DPD, as well as complete a set of core competencies (CRDNs) that are acquired during a supervised practice program or alternative supervised practice hours. A method used by educators to bolster student success and ensure student preparedness is experiential learning (EL) [1]. In the field of dietetics, EL can promote success among students by increasing comprehension and confidence in their ability to translate the knowledge gained in the classroom into real-world practice. The term EL was first coined in 1984 as a method of education that “combines experience, cognition, perception, and behavior” [1].

In dietetics, a primary goal of EL is the translation of didactic education and knowledge into real-world practice by framing learning as a process with distinct steps: acquisition, specialization, and integration [1]. EL activities are beneficial due to their effectiveness to accommodate different learning styles [1], as well as the documented impact, particularly in pre-health professional studies. In a large survey of faculty from U.S. universities, educators reported improvements in their students’ skills in critical thinking, communication, and problem solving when exposed to EL [2]. While the benefits of this method are well recognized, there are often barriers to implementation. For example, instructors have reported challenges related to time, class size, and lack of resources as obstacles to implementing EL in courses [2].

Simulation-based learning experiences (SBLE) are widely supported mechanisms for EL in clinical assessment, characterized by a high degree of realism [3,4,5]. In the late 20th century, SBLE started to be incorporated into standardized training for medical professionals, beginning with simulated training in resuscitation techniques [6]. The Healthcare Simulation Dictionary [7] defines SBLE as activities that “… allow participants to develop or enhance their knowledge, skills, and attitudes, or to analyze and respond to realistic situations in a simulated environment”. SBLE typically take place in a realistic healthcare setting such as a hospital room for a specific patient/case study using either a mannequin or a standardized patient actor [8]. These experiences are then reviewed between students and SBLE instructors. The benefits of instructor feedback and the ability to make mistakes without adverse consequences have been identified as key components of a successful SBLE [9].

Several studies have examined the effectiveness of SBLE in preparing students for real-world practice in a healthcare setting [3,4,10,11]. There have been documented successes in improving knowledge acquisition and critical thinking, both of which are key components of clinical reasoning, through the use of SBLE [12,13]. Repeated exposure to SBLE is also associated with significant gains in clinical and communication skills along with knowledge retention and implementation of technical and non-technical skills such as interdisciplinary collaboration [10,14]. Because of these benefits, SBLE have long been included in the training of new clinicians in various medical fields such as nursing, physical therapy, and medicine [13,15]. However, the practice is not as common in dietetics programs as it is in other healthcare fields [8]. Dietetics students are required to complete a minimum of 1000 h of supervised practice prior to taking a certification exam to become an RDN, but these hours are not solely dedicated to clinical hours as they are also divided among food service management and community nutrition rotations. Furthermore, many do not receive hands-on clinical experience as SBLE or otherwise in their DPD coursework [16].

The Council on Future Practice (CFP), a permanent organized body of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND), the world’s largest organization of nutrition and dietetics professionals, encourages the use of simulation in nutrition and dietetics education [17]. KRDNs and CRDNs can be acquired through SBLE, and SBLE can count towards alternative supervised practice hours. SBLE can additionally benefit future clinicians through interpersonal communication [18] and motivational interviewing skill development [19,20]. Motivational interviewing is a patient-centered counseling approach that uses techniques like empathy and the promotion of self-efficacy to help clients overcome ambivalence and make positive lifestyle changes [21]. This counseling technique has shown great promise as an intervention strategy for diet-sensitive conditions such as obesity and hypertension [22,23]. One study revealed that interpersonal counseling practice with standardized patients was beneficial to dietetics interns by increasing their awareness of counseling techniques, providing them with patient feedback, and increasing their self-confidence [24].

Research indicates that student perception of the learning experience and of their ability to achieve successful interdisciplinary relationships were improved following SBLE experiences. Additionally, it has been found that student self-efficacy and confidence were greatly improved through SBLE [16]. However, because SBLE is less common as a standard component of undergraduate dietetics programs, there have been fewer studies investigating its impact on dietetics students’ perceived preparedness to enter the field as RDNs.

The current study aimed to assess the impact of four successive nutrition care and communication focused SBLE over 9 months throughout upper-level dietetics undergraduate courses on students’ self-perceived confidence to perform technical skills of an entry-level dietitian. We hypothesized that students would experience greater self-confidence and self-reported ability to perform standard tasks of an RDN would improve, thus increasing student preparedness for an entry-level dietetics position.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted at one land-grant institution equipped with a complete medical center in one central location in the United States through the academic department housing the Didactic Program in Dietetics (DPD). The study was implemented in accordance with the Declaration of Helinski, and the protocol was approved at the university’s Institutional Review Board (#54475).

2.1. Sample

Study participants were recruited from a convenience sample of two required undergraduate dietetics degree courses across the 2023 academic semesters. For the study’s purposes, students were asked to complete an online, anonymous survey regarding their confidence with dietetics practice and communication skills and SBLE in their Medical Nutrition Therapy I and II (forwardly called MNT I and MNT II) courses. Students in the dietetics major take the MNT courses typically within their junior and senior years (years 3 and 4 of a 4-year undergraduate degree). The course curricula from MNT I builds into more advanced material in MNT II, and students participate in four SBLE experiences to enhance their clinical and transferable skills. During the second 16-week academic semester, along with MNT II, students concurrently enroll in a Counseling and Communication in Dietetics course. Throughout the counseling course, students learn and practice techniques surrounding nutrition communication such as motivational interviewing, behavior change theories (i.e., transtheoretical model) and developing and teaching groups. Simultaneously during these two academic semesters, students’ progress through their SBLE experiences initially as a part of groups to working individually on their culminating SBLE.

2.2. Simulation-Based Learning Experiences with Standardized Patients

Best practices of impactful SBLE included setting clear expectations and objectives, adopting a progressive approach, varying the experience, and providing meaningful and constructive feedback at multiple points of time [25,26]. In the current study, we implemented those best practices through various approaches to allow students to see their progression in expected skills from one SBLE to the next. The SBLE conducted at the Simulation Center, in collaboration with UK Chandler Hospital, provided an engaging and progressive learning experience for participating students. Each SBLE aimed to provide a real-world experience using standardized patient actors (SP) who are rigorously trained to portray a wide variety of clinical scenarios with diverse backgrounds.

Over nine months, each student engaged in a series of four SBLEs, designed to increase in complexity and challenge. These activities were structured to imitate real-world clinical scenarios, offering students a comprehensive understanding of diverse patients and conditions. Each SBLE began with a pre-brief, where students and the instructors discussed the scenario, objectives, and expectations. A detailed rubric was provided prior to the SBLE pre-brief that clearly outlined expectations for performance, offering clarity and structure that support the students’ understanding of what skills and knowledge are required for success. This pre-brief ensured that students had prepared and demonstrated critical thinking before beginning the SBLE. After the experience, a debrief was conducted to provide students with an opportunity to reflect on their performance, identify areas for improvement, and integrate feedback into future simulations [27,28].

Students were required to complete documentation on the patient and SBLE using the assessment, diagnosis, intervention, monitoring and evaluation (ADIME) documentation format after each experience. This documentation process encouraged students to assess patient needs, formulate appropriate interventions, and evaluate outcomes, mimicking the practices followed in clinical settings.

While each SBLE was unique, a common thread across all was the requirement for students to perform a nutrition-focused physical exam (NFPE). By consistently incorporating the NFPE into each simulation, students had the opportunity to hone their skills in conducting in-depth nutritional assessments and build confidence in their ability to perform the exam. Moreover, some SBLE integrated interdisciplinary teamwork, involving actors portraying roles such as registered nurses (RN), medical doctors (MD), and family members. This interdisciplinary approach enhanced the SBLE, exposing students to collaborative practice and emphasizing the importance of effective communication and teamwork in patient care.

2.3. Study Timeline

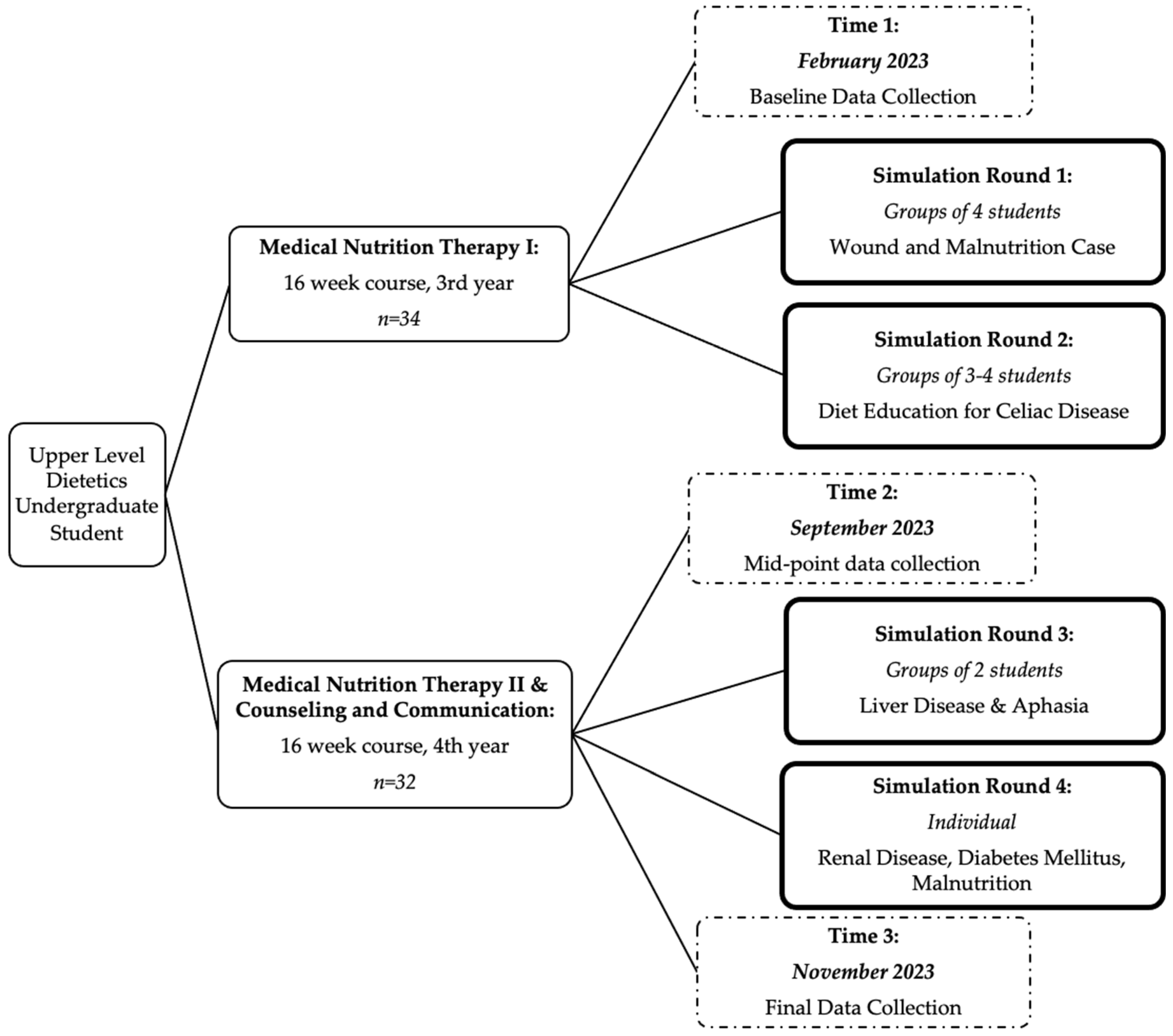

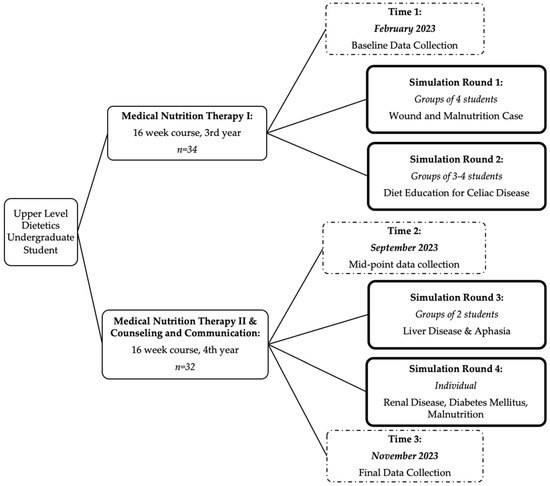

The data collection portion of this study took place outside of course-required assignments during the 2023 calendar year. To ensure students felt comfortable self-selecting to participate, email recruitment was completed by an outside researcher (DPD director) with no affiliation to the course. Each course instructor then encouraged students to complete the surveys through an announcement on course management sites and in class approximately three days following the initial email by the DPD director. The online survey for this study was delivered to students at three time points (Figure 1): (1) prior to their first SBLE in MNT I (time 1; February 2023), (2) prior to beginning MNT II/Counseling (time 2; September 2023), and (3) following final SBLE at the end of MNT II/Counseling (time 3; November 2023). For this timeframe (9 months), students would have completed zero simulations at time 1, two simulations at time 2, and four simulations at time 3. Descriptive survey items included class standing (just starting MNT I, just starting MNT II/Counseling, or just finished MNT II/Counseling), frequency of individual or group simulations they had participated in (range from 0–4), and if they had prior healthcare experience and length of experience (open response of months or years).

Figure 1.

Dietetics Student Simulation Study Overview and Timeline.

Survey tools were used to assess self-perceived confidence in ability as an entry-level RDN including the Perceived Readiness for Dietetics Practice questionnaire [29], a subsection of the Dietetics Confidence Scale (DCS) [30], and an adapted version of the MNT Simulation Evaluation Instrument (MNTSEI) [31]. The Perceived Readiness for Dietetics Practice questionnaire, developed by Farahat and colleagues, aims to measure student readiness for the dietetics profession based on competencies set forth by the Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics. The full Perceived Readiness for Dietetics Practice questionnaire contains 17 Likert item statements across 7 categories of (1) readiness to perform a dietetics role, (2) professional role, (3) communication, (4) patient interaction, (5) charting, (6) referral, and (7) self-reflection. Category 1 Likert item ranged from 1 (not ready) to 10 (very ready) and was used on a continuous scale for analysis. Category 2 Likert item ranged from 1 (not confident) to 5 (very confident) and was used on a continuous scale. Categories 3–7 Likert item ranged from 1 (not confident) to 4 (very confident) and was used on a continuous scale.

The Dietetics Confidence Scale subscale included was calculated from a Likert item scale from 1 (cannot do at all), midpoint of 5 (moderately can do), through 10 (can certainly do). The study’s version of the MNTSEI was adapted for use by two RDN instructors in the study’s implementing department. The original MNTSEI is a 15-item evaluation used by instructors to score student competency during real-time simulation activities. The current use of the MNTSEI was shortened to 9 items adapted for self-reflection by the student participants. Items were assessed on a Likert item scale from 1 (cannot do at all), midpoint of 5 (moderately can do), through 10 (can certainly do) and used on a continuous scale.

Optional open-ended questions were included to receive qualitative feedback regarding SBLE experiences. Four optional open-ended questions included, (1) “how did the simulation experience impact your confidence in providing clinical care?”, (2) “how did the simulation experience impact your confidence in providing patient counseling?”, (3) “how did the simulation experience impact your perceived readiness to serve as an entry-level dietitian?”, and (4) “what additional feedback would you like to add about the simulation experience and what recommendations do you have for improving the simulation experience in future semesters?”.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Basic descriptive variables were assessed by frequency. Means and standard deviations were calculated for continuous Likert scale items. Likert item continuous variables were also analyzed by one-way ANOVA for differences by time. Independent t-tests were used to assess differences by healthcare experience (yes/no), for each Likert item, at each time point. Differences were considered significant at p ≤ 0.05. Responses to the open-ended questions were summarized and provided in illustrative quotes based on the resulting themes from each question.

3. Results

Between 21 and 24 undergraduate student participants completed the survey at each time point (70.6% and 65.6% of total possible students, respectively) (Table 1). Self-reported length of healthcare experiences increased from baseline (starting MNT I) to final collection (completed MNT II/Counseling). By the end of the study, each student had engaged in 3 group simulations and 1 individual simulation.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the dietetics student study population.

Across most Likert items, participants’ readiness for the dietetics profession significantly increased across the study timeframe. Nine of 39 total items did not show significant increases among the cohort but remained relatively stable through each time point (Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4). Healthcare experience was also examined among each Likert item in each scale to assess if confidence in their skills in dietetics training was impacted by their experiences. At baseline, there were no significant differences among confidence for those with or without healthcare experience (p > 0.05).

Table 2.

Perceived readiness for dietetics practice (perceived readiness for dietetics practice outcomes.

Table 3.

Dietary confidence scale (DCS) subset outcomes.

Table 4.

Adapted medical nutrition therapy simulation evaluation instrument (MNTSEI) outcomes.

After MNT I (Time 1; following two group simulations), those with healthcare experience had higher confidence among 12 of the 39 items (Table 2) (all p’s < 0.05). At the final time point (completion of MNT II/Counseling course and four simulation experiences) those with healthcare experience had higher confidence among just four of the 39 total items (p < 0.05). These four items included, “applying leadership skills to achieve desired outcomes in various groups” (3.82 ± 0.20 vs. 4.50 ± 0.23; p = 0.0336), “referring clients and patients to other professionals and services when needs are beyond individual scope” (2.64 ± 0.21 vs. 3.38 ± 0.29; p = 0.0429), “obtain nutrition-focused physical findings” (7.73 ± 0.64 vs. 9.63 ± 0.74; p = 0.0039), and “identify appropriate nutrition-related markers to monitor/evaluate based on nutrition intervention” (7.82 ± 0.62 vs. 9.13 ± 0.69; p = 0.0336).

All markers of the DCS questionnaire (Table 3), except “look for something positive to acknowledge” and “see things from a client’s point of view”, significantly improved across time. The two nonsignificant statements were also the two highest starting averages among the group. Likewise, among the adapted MNTSEI (Table 4), “demonstrate proper hand hygiene” was the highest scored statement at baseline and remained high across time and saw no significant increase. Among the other MNTSEI there were significant increases in each over timepoint.

Finally, students were asked four optional open-ended questions regarding their thoughts on the simulation experiences. Though there was a lower response rate (8–13 responses for each question across all time points), similarities were identified among the responses (Table 5). Of question 1 responses (“how did the simulation experience impact your confidence in providing clinical care?”; n = 13 (61.9%)), eight students highlighted feeling more “confident” or “comfortable” with providing nutrition care. Two students mentioned that the simulations helped and gave them real life scenarios, while one participant mentioned it improved their abilities but realized they still are not where they want to be yet (post MNT II; Time 3).

Table 5.

High-fidelity simulation qualitative responses.

Among question 2 responses (“how did the simulation experience impact your confidence in providing patient counseling?”; n = 12; (57.1%)), all students identified that the simulation experience was beneficial in helping them feel confident in their counseling skills. Likewise, for question 3 (“how did the simulation experience impact your perceived readiness to serve as an entry-level dietitian?”; n = 11 (52.4%)), all were positive responses regarding their readiness following simulations. Responses ranged from agreeing that the simulations improved their skills or helped them feel more prepared on what to expect in their future career.

Finally, from question 4 responses (“what additional feedback would you like to add about the simulation experience and what recommendations do you have for improving the simulation experience in future semesters?”; n = 9 (42.9%)), two participants mentioned that the individual simulation experiences were viewed as more challenging but a better experience for building confidence and leadership skills. Likewise, two participants mentioned wishing there were more simulation experiences throughout their coursework with one indicating desire for all individual simulation opportunities rather than completing some as a group.

4. Discussion

Outcomes from this project demonstrated that, across three time points, SBLE experiences with DPD coursework increased students’ self-perceived confidence and self-perceived ability to perform the technical skills of an entry-level dietitian. This was found in students both with and without prior healthcare experience. These improved outcomes are similar to several other studies among simulation experiences in dietetics [29,32,33,34,35].

Unlike most studies of SBLEs for dietetics students, we considered prior healthcare experience in our data analyses. Though several baseline confidence items were significantly lower among students without healthcare work experience, ratings in confidence at the final measurement generally leveled out to equal perceived confidence between the groups. At baseline, those with healthcare work experience had significantly higher confidence among 12 of the 39 items, which decreased to only four of the 39 items at the final time point. Having healthcare experience seemed to benefit confidence in performing the following tasks: “applying leadership skills to achieve desired outcomes in various groups”, “referring clients and patients to other professionals and services when needs are beyond individual scope”, “obtain nutrition-focused physical findings”, and “identify appropriate nutrition-related markers to monitor/evaluate based on nutrition intervention”. Findings seem to indicate that the confidence level between those with and without prior healthcare experience aligns over time due to participating in SBLE. This could indicate a greater benefit of SBLE to those students who cannot acquire adequate clinical experience due to extenuating circumstances (i.e., COVID-19 precautions) or limited availability of such clinical opportunities.

SBLE allows students to increase their perceived ability to effectively perform the technical aspects of clinical dietetics. Results from this study support similar findings [13,15] that SBLE strengthens clinical reasoning and critical thinking. Collectively, students indicated their ability to effectively demonstrate counseling skills improved, which supports findings from past research on SBLE for dietetics students [16]. Buchholz and colleagues are one of the only studies, to our knowledge, that assessed both nutrition care and communication skills [36]. The researchers found that students completing undergraduate dietetics coursework and SBLE with standardized patients also significantly increased on 11 communication and collaboration performance indicators (i.e., using appropriate communication technique(s)) and eight nutrition-care performance indicators (i.e., obtaining and interpreting medical history) [36]. In the current study, students demonstrated continuous improvement in professional competencies and transferable skills—notably in charting, adaptability, negotiation, and cooperation. This continuous improvement supports the results of prior studies which have indicated that repeated simulation experiences over time lead to greater knowledge retention and improved technical skills [14]. Also, students seemed to benefit from transitioning from group to individual work over the four SBLEs. Specifically, students built their skills over time before providing care as an individual at the culminating SBLE. Beginning with group-based simulations encouraged collaboration while building initial confidence. As the experiences progressed and students demonstrated proficiency, a gradual transition to a smaller group SBLE and then a final individual simulation promoted autonomy and mastery by allowing students to apply their newly developed skills independently.

Findings from the current study show various confidence indicators did not significantly increase across time for the full cohort. Items such as “looking for something positive to acknowledge”, “seeing things from a client’s point of view”, and “demonstrating proper hand hygiene” were initially scored at a higher confidence rate, indicating students were already comfortable completing these skills prior to SBLE, and scores remained uniform across the time points. On the other hand, several indicators of confidence that were rated relatively low at Time 1 did not see significant changes such as “communication with dietitians or supervisors”, “communication with healthcare professionals”, and “demonstrating active participation in teams.” This is notable given that prior studies have supported SBLE as a successful tool for improving interdisciplinary teamwork [5]. In the present study, SBLE had actors who also served as the healthcare team (i.e., nurses) with whom the students have a brief interaction with during the experience. SBLE with SPs should be designed to coordinate care with other healthcare professionals such as registered nurses (RNs) or medical doctors (MDs). By exposing students to a variety of SBLE experiences, instructors can enhance students’ preparedness and confidence in addressing the complexities of dietetics practice. Finding deeper opportunities for students to practice communication with multidisciplinary teams or supervisors could be a beneficial addition to future SBLE or DPD coursework.

To note, “communicating with patients from diverse population (such as being familiar with various cultural foods and habits)” was a measure that began and remained lower on confidence rating for the participants across the four SBLEs. Over the course of the two semesters, students interacted with patients that had different ages, sex, backgrounds, and conditions exposing them to experiences that simulate scenarios typically encountered in clinical settings. However, continued emphasis is needed on teaching students how to effectively communicate with patients from diverse populations and cultural patterns to improve their confidence in diverse meal and nutritional patterns. Several non-dietetics fields, such as medical and nursing, have studied the use of culturally diverse simulation patients with success around cultural competence and care [37,38,39].

Finally, qualitative feedback from participants indicated that students report SBLEs as a valuable learning opportunity. Collectively, respondents indicated improvements across almost all measures in this study. From the qualitative findings, respondents specifically appreciated the ability to put their education into practice and to see their full potential as future clinical RDNs. Respondents shared a sense of pride and accomplishment since their final SBLE was completed individually where they could showcase their skills.

Providing comprehensive, consistent, and constructive feedback at various stages of the SBLE is critical for student development. In prior studies, students consistently noted the value in post-simulation debriefing sessions, often identifying it as the most valuable aspect of the simulation experience [14]. For example, students receive oral feedback both before and after each SBLE, allowing for real-time reflection and adjustment, and written feedback on rubrics, outlining strengths and areas for improvement. Additionally, to maximize the effectiveness, prior feedback from previous SBLE experiences should be revisited to track progress and recognize growth over time. This effectively reinforces students’ confidence and encourages continuous improvement. Integrating these strategies into SBLE environments can effectively enhance the confidence and preparedness of dietetics students, equipping them with the skills and knowledge needed for success in their future careers.

Limitations

While the study succeeded in explaining confidence building across SBLE and upper-level dietetics undergraduate courses, the methodology was not without limitations. It is important to note that, while we did see improvements in confidence toward dietetics practice skills, students were simultaneously enrolled in two MNT courses and one counseling course across the 9-month study period. Due to this, we cannot strictly parse out the effects of the SBLE, comparative to the standard increase in knowledge from the typical information gathering from the courses. Throughout the MNT courses, information and skills build upon each other from basic clinical content (i.e., obesity, diabetes) to higher level (i.e., liver disease, kidney disease). We can assume that a portion of the student’s confidence and readiness for the dietetics field could come from the course content alone. In this study, we utilized a convenience sample of students involved in MNT courses and completing SBLE experiences. As such, there was not a control group, and we had an overall small sample size. Future studies may benefit from a comparison of preparedness from a course only approach and a course and SBLE approach.

Among the questionnaire items, there are a few noted limitations as well. Due to the self-reported survey nature of this study, reliability of the data should be taken with caution due to self-reporting biases. Though we did see a natural, steady improvement in confidence, care should be taken when generalizing to other dietetics student populations. This should also be cautioned due to the difference in course content shared in MNT courses. Though courses that are part of an accredited dietetics program follow standardization for the skills and knowledge students should gain throughout a four-year program, instructor pedagogy and teaching-styles differ. Likewise, among these SBLE experiences, case study topics and assignment rubrics would differ by the program and are chosen at the instructor’s discretion.

Finally, within our survey measures, adaptations were made of the questionnaires. For the Perceived Readiness for Dietetics Practice tool, Likert scale for the “professional role” section of the Perceived Readiness for Dietetics Practice questionnaire was given on a scale of 1–5 rather than the intended 1–4 scale of “not confident” (1) to “very confident” (2). The published Likert item survey by Farahat and colleagues [29] has each item on a 1–4 scale. The 1–5 scale given to a portion of our survey was an oversight by investigators and should be corrected in future survey collection. Likewise, a subset of the DCS, and adaptation of the MNTSEI were used for this study to capture an accurate representation of what student skills were measured in the course and SBLE, as well as to reduce participant burden.

Overall, important considerations for future investigation should consider larger sample sizes, objective measures of skill (i.e., via instructor feedback and objective clinical skill assessment such as PSE statement/clinical charting and writing), and integration of controlling for confounding factors (i.e., course content and instructor pedagogy differences between institutions). Consideration of the impact that participating in SBLE could have on several key measures of DPD program success could warrant understanding. Such items include the impact of SBLE participation on the RDN credentialing exam pass rate and on eventual employer satisfaction with the entry-level practice readiness of graduates. Likewise, as DPD programs, and requirements for becoming a registered dietitian are changing to acquire a master’s level degree or higher, consideration should be taken of differing levels of confidence and abilities within graduate degree programs. Confidence and critical thinking skills should be increased in a graduate-prepared student, but they still have room for growth and improvement throughout their didactics courses. However, since not all graduate programs are clinically focused, it might still be appropriate to complete similar case studies with graduate students as basic knowledge and skills will still be necessary. Future studies should consider the use of SBLEs in graduate education and the varying levels of difficulty in case-study simulations. Finally, future research could identify if SBLE experience translates into greater student success at meeting CRDNs, most notably in Domain 3: clinical and customer services; development and delivery of information, products, services to individuals, groups, and populations. This type of future research could help build the support for SBLE to be considered an evidence-based instruction method that can be prioritized in undergraduate dietetics programs.

5. Conclusions

Academic institutions provide undergraduate instruction and learning opportunities to prepare students for professional careers. In this study, we utilized SBLE with dietetics students to learn and practice skills they would use in an entry-level clinical position. Across two academic semesters, students completed four simulation activities, three group simulations, and one final individual simulation experience. SBLEs were found to be an effective addition to classroom material in this study. These findings supported our hypothesis that students would experience greater self-confidence and that their perceived ability to perform standard tasks of an RDN would improve, thus increasing their preparedness for an entry-level dietetics position. Across these experiences, student participants self-reported higher readiness and confidence for their skills and abilities in the dietetics profession. While student confidence increased across the cohort, SBLEs were particularly beneficial in equaling the level of confidence in skills between those with prior clinical experience and those without.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.-P., E.C., D.B., A.S. and T.S.; Data curation, M.B.-P.; Formal analysis, M.B.-P.; Investigation, M.B.-P., L.B., D.B., A.S. and T.S.; Methodology, M.B.-P., E.C., D.B., A.S. and T.S.; Project administration, M.B.-P.; Writing—original draft, M.B.-P., E.C., L.B., D.B. and A.S.; Writing—review and editing, M.B.-P., E.C., L.B., D.B., A.S. and T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board (#54475).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon reasonable request to authors.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank student participants for their time and data for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; FT Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wurdinger, S.; Allison, P. Faculty perceptions and use of experiential learning in higher education. J. E-Learn. Knowl. Soc. 2017, 13, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, J.M.; Rossler, K. The how when why of high fidelity simulation. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, B.W.; Carter, O.B.-J.; Rudd, C.J.; Claxton, L.A.; Ross, N.P.; Strobel, N.A. Effects of Low- Versus High-Fidelity Simulations on the Cognitive Burden and Performance of Entry-Level Paramedicine Students: A Mixed-Methods Comparison Trial Using Eye-Tracking, Continuous Heart Rate, Difficulty Rating Scales, Video Observation and Interviews. Simul. Healthc. 2016, 11, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lateef, F. Simulation-based learning: Just like the real thing. J. Emergencies Trauma Shock 2010, 3, 348–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, P. The history of simulation in medical education and possible future directions. Med. Educ. 2006, 40, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lioce, L.; Lopreiato, J.; Downing, D.; Chang, T.; Robertson, J.; Anderson, M.; Diaz, D.; Spain, A.; Terminology; Group, C.W. Healthcare simulation dictionary. Rockv. MD Agency Healthc. Res. Qual. 2020, 2020, 20-0019. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, K.L.; Gutschall, M.D. The time is now: A blueprint for simulation in dietetics education. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 2, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry Issenberg, S.; McGaghie, W.C.; Petrusa, E.R.; Lee Gordon, D.; Scalese, R.J. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: A BEME systematic review. Med. Teach. 2005, 27, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, J.G.; Hafiz, A.H.; Eltohamy, N.A.E.; Gomma, N.; Al Jarrah, I. Repeated exposure to high-fidelity simulation and nursing interns’ clinical performance: Impact on practice readiness. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2021, 60, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Wong, T. High-fidelity simulation training programme for final-year medical students: Implications from the perceived learning outcomes. Hong Kong Med. J. 2019, 25, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapkin, S.; Levett-Jones, T.; Bellchambers, H.; Fernandez, R. Effectiveness of patient simulation manikins in teaching clinical reasoning skills to undergraduate nursing students: A systematic review. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2010, 6, e207–e222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, P. Effects of an experiential learning program on the clinical reasoning and critical thinking skills of occupational therapy students. J. Allied Health 2010, 39, 280–286. [Google Scholar]

- E J, S.K.; Purva, M.; Chander, M.S.; Parameswari, A. Impact of repeated simulation on learning curve characteristics of residents exposed to rare life threatening situations. BMJ Simul. Technol. Enhanc. Learn 2020, 6, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter Beest, H.; van Bemmel, M.; Adriaansen, M. Nursing student as patient: Experiential learning in a hospital simulation to improve empathy of nursing students. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2018, 32, 1390–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, J.D.; McCarroll, C.S.; Nucci, A.M. High-fidelity patient simulation increases dietetic students’ self-efficacy prior to clinical supervised practice: A preliminary study. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2016, 48, 563–567.e561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kicklighter, J.R.; Dorner, B.; Hunter, A.M.; Kyle, M.; Prescott, M.P.; Roberts, S.; Spear, B.; Hand, R.K.; Byrne, C. Visioning report 2017: A preferred path forward for the nutrition and dietetics profession. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameg, K.; Howard, V.M.; Clochesy, J.; Mitchell, A.M.; Suresky, J.M. The impact of high fidelity human simulation on self-efficacy of communication skills. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2010, 31, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galal, S.; Vyas, D.; Mayberry, J.; Rogan, E.L.; Patel, S.; Ruda, S. Use of standardized patient simulations to assess impact of motivational interviewing training on social–emotional development. Pharmacy 2018, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.P.; Cassalia, J.; Warunek, M.; Scherer, Y. Motivational interviewing training with standardized patient simulation for prescription opioid abuse among older adults. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2019, 55, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noonan, W.C.; Moyers, T.B. Motivational interviewing. J. Subst. Misuse 1997, 2, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M.; Mottershead, T.; Ronksley, P.; Sigal, R.; Campbell, T.; Hemmelgarn, B. Motivational interviewing to improve weight loss in overweight and/or obese patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Xu, N.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Guo, A. The effects of motivational interviewing on hypertension management: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2023, 112, 107760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, B.W.; Duellman, M.C.; Smith, T.J. Nutrition-based standardized patient sessions increased counseling awareness and confidence among dietetic interns. Top. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 24, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, A.E.; Boese, T.; Gloe, D.; Lioce, L.; Decker, S.; Sando, C.R.; Meakim, C.; Borum, J.C. Standards of best practice: Simulation standard IV: Facilitation. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2013, 9, S19–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lioce, L.; Meakim, C.H.; Fey, M.K.; Chmil, J.V.; Mariani, B.; Alinier, G. Standards of best practice: Simulation standard IX: Simulation design. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2015, 11, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.; Tori, K. Best practice recommendations for debriefing in simulation-based education for Australian undergraduate nursing students: An integrative review. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2017, 13, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sittner, B.J.; Aebersold, M.L.; Paige, J.B.; Graham, L.L.; Schram, A.P.; Decker, S.I.; Lioce, L. INACSL standards of best practice for simulation: Past, present, and future. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2015, 36, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farahat, E.; Rice, G.; Daher, N.; Heine, N.; Schneider, L.; Connell, B. Objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) improves perceived readiness for clinical placement in nutrition and dietetic students. J. Allied Health 2015, 44, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buttenshaw, K.; Ash, S.; Shakespeare-Finch, J. Development and validation of the Dietetic Confidence Scale for working with clients experiencing psychological issues. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 74, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaii-Waite, S. Medical Nutrition Therapy Simulations; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea, M.-C.; Reeves, N.E.; Bialocerkowski, A.; Cardell, E. Using simulation-based learning to provide interprofessional education in diabetes to nutrition and dietetics and exercise physiology students through telehealth. Adv. Simul. 2019, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, H.H.; Cameron, J.; Wiesmayr-Freeman, T.; Swanepoel, L. Perceived benefits of a standardized patient simulation in pre-placement dietetic students. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, T.; Moritoshi, P.; Sato, K.; Kawakami, T.; Kawakami, Y. Effect of simulated patient practice on the self-efficacy of Japanese undergraduate dietitians in nutrition care process skills. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, S.; Davidson, Z. An observational study investigating the impact of simulated patients in teaching communication skills in preclinical dietetic students. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 29, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, A.C.; Vanderleest, K.; MacMartin, C.; Prescod, A.; Wilson, A. Patient simulations improve dietetics students’ and interns’ communication and nutrition-care competence. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.R.; Gianola, M.; Perry, J.M.; Losin, E.A.R. Clinician–patient racial/ethnic concordance influences racial/ethnic minority pain: Evidence from simulated clinical interactions. Pain Med. 2020, 21, 3109–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T. An Innovative Educational Strategy to Influence Cultural Competence Utilizing Clinical Simulation with Diverse Standardized Patients. Ph.D. Thesis, Carlow University, Pittsburgh, PE, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Karnitschnig, L.M.; Eddie, R.; Schwartz, A.L. Applying diversity principles and patient-centered, cultural curriculum through simulation and standardized patient actors. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2023, 77, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).