Reflections on Initial Teacher Education and Theoretical Framing of Applied Pedagogical Knowledge with a Context-Consciousness: An International Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

“In the school where I did practice teaching, things happen very differently from what we learned in our studies. Quite honestly, I felt lost and am no longer sure that I want to become a teacher”.(Preservice teacher, South Africa)

2. Theoretical Framework and Methodology

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Methods

3. Findings: Voices from the Field

3.1. Preservice Teachers’ Narratives: Lived Experiences

3.1.1. Defective Professional Knowledge: Exploring Teaching Practices and the Gap between Theory and Practice

3.1.2. Restricted Professional Knowledge Limits Effective Learning in Practice

3.2. Development of Professional Knowledge during Preservice Teachers’ Teaching Practice

3.2.1. Mentoring Facilitates the Development of Context-Appropriate Professional Knowledge

3.2.2. An Enabling School Atmosphere/Culture Improves Preservice Teachers’ Professional Knowledge

3.3. School Mentors’ Narratives: Preservice Teachers’ Restricted Professional Knowledge

3.4. Mentoring “Unsound” Professional Knowledge of Preservice Teachers

3.5. Linking the Power of Knowledge to a Presence in the Classroom

3.6. Professional Identity Embedded in a Sound Professional Knowledge Base

3.7. Professional Knowledge Development beyond ITE through Collaboration

3.8. Ongoing Teacher Capacity Building

3.9. Critical Reflection on Practices: Implications for further Development of Professional Knowledge

School Leaders’ Reflections: Beginning Teachers’ Preparedness and Readiness

4. Discussion

4.1. Professional Knowledge

4.2. Professional Knowledge and an Enabling School Environment

4.3. Quality Mentoring

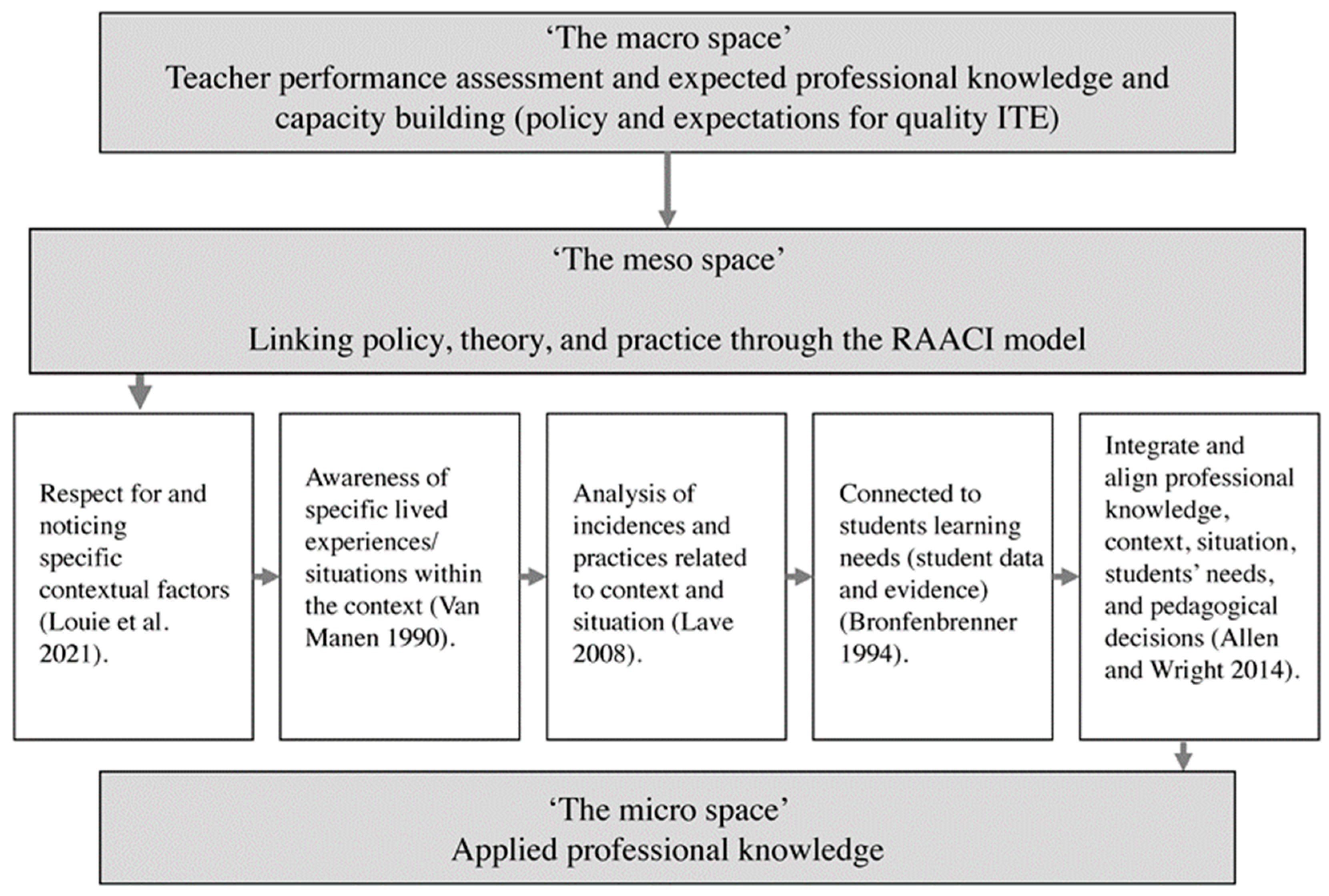

4.4. Professional Knowledge and Teacher Capacity Building: The RAACI Model

4.5. Professional Knowledge Development: Collaboration/Partnerships

5. Limitations of the Current Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cosgun, G.; Derin, A. Coaching Applications and Effectiveness in Higher Education; Hunaiti, Z., Ed.; IGI Global Publisher of Timely Knowledge: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 181–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, A.P.; Goosen, L. Handbook of Research on Reconceptualizing Preservice Teacher Preparation in Literacy Education; IGI Global Publisher of Timely Knowledge: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, L.; Klein, J.; Mayer, D. Early Career Teachers’ Perceptions of their Preparedness to Teach ‘Diverse Learners’: Insights from an Australian Research Project. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2017, 42, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). The Australian Professional Standards for Teachers; Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership: Melbourne, Australia, 2018; Available online: http://www.aitsl.edu.au/australian-professional-standards-for-teachers (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- South African Council for Educators. South African Council for Educators. Professional Teaching Standards. SACE. 12 October 2020. Available online: https://www.sace.org.za/assets/documents/uploads/sace_31561-2020-10-12-Professional%20Teaching%20Standards%20Brochure.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Smith, C. Why Should We Bother with Assessment Moderation? Nurs. Educ. Today 2012, 32, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group, TEMAG. Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers; Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group: Melbourne, Australia, December 2014. Available online: https://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/other/action_now_classroom_ready_teachers_accessible.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- Thiel, F.; Böhnke, A.; Barth, V.L.; Ophardt, D. How to Prepare Preservice Teachers to Deal with Disruptions in the Classroom? Differential Effects of Learning with Functional and Dysfunctional Video Scenarios. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2023, 49, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Akin, S.; Goodwin, A.L. Teacher Candidates’ Intentions to Teach: Implications for Recruiting and Retaining Teachers in Urban Schools. J. Educ. Teach. 2019, 45, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, L.T.; Le, T.T.; Henderson, F. Rite of Passage into the Teaching Profession? Australian Pre-Service Teachers’ Professional Learning in the Indo-Pacific through the New Colombo Plan. Teach. Teach. 2021, 27, 542–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran-Smith, M.; Boston College Evidence Team. Re-culturing Teacher Education: Inquiry, Evidence and Action. J. Teach. Educ. 2009, 60, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C. A Bourdieuian Analysis of Teachers’ Changing Dispositions towards Social Justice: The Limitations of Practicum Placements in Preservice Teacher Education. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2013, 41, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABC (Australian Broadcast Corporation) News. As Ministers Call for More People to Become Teachers, Some Are Still Struggling to Find a Permanent Job. ABC. 22 August 2022. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-08-22/teacher-job-insecurity-worker-shortage/101340174 (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Why South Africa Will Find It Hard to Break Free from Its Vicious Teaching Cycle. The Conversation. 7 January 2019. Available online: https://theconversation.com/why-south-africa-will-find-it-hard-to-break-free-from-its-vicious-teaching-cycle-108698 (accessed on 13 January 2019).

- Du Plessis, A.E. A Handbook for Retaining Early Career Teachers: Research-Informed Approaches for School Leaders; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Louie, N.; Adiredja, A.P.; Jessup, N. Teacher Noticing from a Sociopolitical Perspective: The Fair Framework for Anti-Deficit Noticing. ZDM Math. Educ. 2021, 53, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Manen, M. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J. Epilogue: Situated Learning and Changing Practice. In Community, Economic Creativity, and Organization; Amin, A., Roberts, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological Models of Human Development. In International Encyclopedia of Education, Volume 3, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 1994; Reprinted in Gauvain, M.; Cole, M. (Eds.); Readings on the Development of Children, 2nd ed.; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.M.; Wright, S.E. Integrating Theory and Practice in the Pre-Service Teacher Education Practicum. Teach. Teach. 2014, 20, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis Anna, E. Professional Support Beyond Initial Teacher Education: Pedagogical Discernment and the Influence of Out-of-Field Teaching Practices; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Du Plessis, A.E.; Cullinan, M.; Gramotnev, G.; Gramotnev, D.K.; Hoang, N.T.; Mertens, L.; Roy, K.; Schmidt, A. The Multilayered Effects of Initial Teacher Education Programs on the Beginning Teacher Workforce and Workplace: Perceptions of Beginning Teachers and their School Leaders. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 99, 101488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis Anna, E. Out-of-Field Teaching and Education Policy: Examining the Practice-Policy Phenomenon; Springer: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Beebe, J. Basic Concepts and Techniques of Rapid Appraisal. Hum. Organ. 1995, 54, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, D.J. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alhamdan, B.; Al-Saadi, K.; Baroutsis, A.; Du Plessis, A.; Hamid, O.M.; Honan, E. Media Representation of Teachers across Five Countries. Comp. Educ. 2014, 50, 490–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamberelis, G.; Dimitriadis, G. On Qualitative Inquiry: Approaches to Language and Literacy Research; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Durksen, T.L.; Klassen, R.M. The Development of a Situational Judgement Test of Personal Attributes for Quality Teaching in Rural and Remote Australia. Aust. Educ. Res. 2018, 45, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, J. What Expert Teachers Do: Enhancing Professional Knowledge for Classroom Practice; Allen & Unwin: Crow’s Nest, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Beijaard, D.; Meijer, P.C.; Verloop, N. Reconsidering Research on Teachers’ Professional Identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2004, 20, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, K.; Henderson, R. Engaging with Images and Stories: Using a Learning Approach to Develop Agency of Beginning ‘At Risk’ Preservice Teachers. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2008, 33, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daza, V.; Gudmundsdottir, G.; Lund, A. Partnerships as Third Spaces for Professional Practice in Initial Teacher Education: A Scoping Review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 201, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, J. Losing Our Way? Challenging the Direction of Teacher Education in Australia by Reframing it around the Socially Just School. Asia Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2013, 41, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P.; Passeron, J.-C. Introduction: Language and Relationships to Language in the Teaching Situation. In Academic Discourse: Linguistic Misunderstanding and Professorial Power; De Saint Martin, L.C., Ed.; Teese, R., Translator; Policy Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

| Research Lenses | Participants | Sample of Participants | Context | Demographic Information | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A South African Lens | Preservice teachers and their mentors | Final-year student teachers completing their practice teaching (narratives received, N = 4413; narratives with in-depth reflections and detailed information selected, n = 27) and the school-based mentors assigned to support them (narratives received, N = 2818; narratives selected with in-depth reflections and detailed information, n = 21) | Bachelor of Education (BEd) Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) (Senior phase, Further Education and Training [FET]). Preservice student teachers and mentors assigned to support them | Teacher education students; largest distance-education university in South Africa. Around 50% of all the teachers and school-based mentors are or were involved in this university. | Qualitative: narratives of preservice teachers’ and mentors’ experiences during professional placement |

| An Australian Lens (WA) | Practicing beginning teachers (within the transition phase to teaching) and their school leaders | Beginning teachers (n = 9) School leaders (n = 14) Education directors (n = 3) Assistant director (n = 1) Parents (n = 10) | Rural, remote, and metropolitan public and independent schools High schools Primary schools District and regional education offices | Western Australia (WA). | Qualitative: semi-structured one-on-one interviews |

| An Australian Lens (QLD) | Practicing beginning teachers (within the first 5 years of teaching) and their school leaders | Beginning teachers (survey respondents N = 1362; interview participants n = 38) School leaders (open-ended survey questions N = 763; interview participants n = 9) | Rural and metropolitan public and independent schools High schools Primary schools | Queensland (QLD). | Qualitative: surveys (open-ended questions) and semi-structured one-on-one interviews |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Du Plessis, A.E.; Dreyer, J. Reflections on Initial Teacher Education and Theoretical Framing of Applied Pedagogical Knowledge with a Context-Consciousness: An International Study. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050448

Du Plessis AE, Dreyer J. Reflections on Initial Teacher Education and Theoretical Framing of Applied Pedagogical Knowledge with a Context-Consciousness: An International Study. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(5):448. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050448

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu Plessis, Anna Elizabeth, and Johann Dreyer. 2024. "Reflections on Initial Teacher Education and Theoretical Framing of Applied Pedagogical Knowledge with a Context-Consciousness: An International Study" Education Sciences 14, no. 5: 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050448

APA StyleDu Plessis, A. E., & Dreyer, J. (2024). Reflections on Initial Teacher Education and Theoretical Framing of Applied Pedagogical Knowledge with a Context-Consciousness: An International Study. Education Sciences, 14(5), 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050448