Abstract

This study investigates parents’ perceptions on school management practices for children with special educational needs in a small-sized Indonesian school. Data from surveys and interviews with 53 parents revealed overall positive attitudes toward classroom management and teacher care. However, concerns arose regarding teachers’ ability to support special needs students effectively, leading to hesitancy in collaborating for inclusive classrooms. To reorient parental perceptions to create conditions for successful inclusive education, effective communication strategies emphasizing teacher development and district-based support are crucial. Future research should focus on improving communication between parents to foster inclusive educational practices. These findings shed light on challenges and solutions for cultivating inclusive classroom environments in special education.

1. Introduction

Rooted in the Education for All framework initiated in Jomtien, Thailand in 1990, the Salamanca Statement emphasizes the core idea of inclusive schooling—where all children, regardless of difficulties or differences, learn together whenever possible [1]. A few years later, the Salamanca Conference of 1994 marked a pivotal moment, establishing the principle of education for all and providing guidelines for the inclusion of children and young people with special educational needs (SEN), also known as inclusive education [2].

In 2012, UNICEF similarly reaffirmed the right of children with special needs to education within regular school settings, aligning with the principles of the Salamanca Statement. In addition, the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities has been instrumental in driving policy changes toward inclusive education. This convention advocates for access to mainstream schools without discrimination, aiming to foster learning and well-being in inclusive environments [3].

To comply with those goals, in recent years, governments worldwide have increasingly recognized the importance of inclusive education for students with diverse needs [4] and have been tasked with making many changes to recognize these diverse needs by providing appropriate support through tailored curricula, teaching methods, and community partnerships. Across the Asia-Pacific region, extensive educational reforms are underway to integrate these learners into mainstream schools—educational institutions that primarily serve typically developing students without significant disabilities or special needs [5]. Despite global efforts, significant barriers persist in meeting these inclusive education goals [6], while there remains considerable variation among countries, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region [7,8,9].

Challenges impeding the success of inclusive education persist in many areas, stemming from various factors, encompassing socio-economic factors, school policies, and administrative systems, leading to inflexible environments and curricula [10,11,12,13]. Significant research has identified additional barriers, including a shortage of personnel with a background in special education or insufficient training in inclusive education [14,15,16,17]. Leadership vision, as noted by [18], can also play a pivotal role in steering or impeding education management toward inclusion, as seen in Malaysia and Thailand, where school leaders can either facilitate or impede effective inclusion processes [17,19].

Moreover, a scarcity of qualified teachers who have knowledge, understanding, and extensive field experience in providing inclusive education or caring for children with SEN is a phenomenon that leads to some schools refusing to include this group of children on the basis that teachers are ill equipped to teach them [20]. The deficiency results in an abundance of teachers lacking the knowledge and skills required for instructing students in an inclusive classroom is another problem contributing to the failure of the successful adoption of inclusive education principles in schools [21].

Although there are many factors that negatively impact the success of creating an environment suitable for inclusive education, this study specifically concentrates on the perception of parents of students with SEN toward the educational management of the school. In instances where the environment for inclusion and the preparedness of personnel to provide inclusive education are well established, challenges persist in achieving inclusive education. It is believed that when this perception does not align with the manifested reality, it is likely to impede the optimal progress of the thriving emergence of inclusive education, potentially rendering it not possible at all. The overarching goal of this study is to propose a strategy to reorient parental perceptions to create conditions for successful inclusive education.

1.1. The Problem

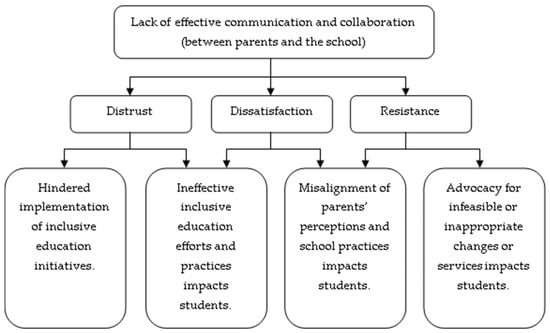

As mentioned above, one potential problem that could arise from this situation is the lack of effective communication and collaboration between parents and the school [22]. If parents’ perceptions of the school’s management and their understanding of inclusive education are misaligned with the actual practices and efforts of the school, it could lead to distrust, dissatisfaction, and resistance from parents [23]. This lack of alignment may hinder the school’s ability to effectively implement inclusive education initiatives and create a supportive environment for students both regular and with SEN [24]. In addition, it may also result in parents advocating for changes or services that may not be feasible or appropriate for the school to provide, further complicating the situation [25].

Several theories in the area of relationships define the term “relationship” as the activities directed toward establishing, developing, maintaining, and retaining successful relations [26,27,28]. These theories have also made it clear that good relationships with all stakeholders enhance efficiency and effectiveness. However, even though maintaining a good relationship seems easy, in reality, not all relationships are always good all the time.

The reason why maintaining good relationships or preventing conflicts in a relationship is not an easy task can derive from many reasons, one of them being differences in perceptions and values [29,30]. From an economic perspective, choosing to maintain or neglect a relationship is an economic decision that often involves weighing costs and benefits. This decision can vary based on individual beliefs about what is considered good and how to establish goodness. Individuals may prioritize self-interest or helping others, leading to differing moral judgments. Additionally, conflicts can arise in relationships when there are conflicts of interest, lack of transparency, favoritism, or nepotism, which can impact the perception of fairness and trust within the organization [31].

Likewise, in the context of schools as educational service providers and parents, maintaining positive and conflict-free relationships is not always easy [32]. Decisions to maintain or damage a good relationship between these two parties also involve weighing the costs and benefits, which means considering different approaches made by each party as an investment in the trust relationship. Less investment implies less confidence from the other side to reciprocate in a relationship. These decisions may vary based on individual beliefs about what constitutes an ideal norm for effective education as perceived by each party [33].

The debate between the interests of the school and the interests of the parents can shape ethical dilemmas [34]. The perception from parents that the school may prioritize the school’s reputation or academic outcomes over the well-being of their children, particularly those with SEN, while parents may prioritize the well-being and individual needs of their children with SEN over the academic standard and the rest of the student population, leads to conflicting interests. This can hinder the efficient promotion of a good relationship built on trust and inevitably obstruct the successful adoption of inclusive education principles. This tension between the school’s goals and the parents’ goals can lead to differing moral judgments and potential conflicts [35,36].

Moreover, ethical conflicts can arise in the relationship between schools and parents when there are concerns about transparency, favoritism, or nepotism within the educational system. For example, parents may feel distrustful if they perceive that certain students or families receive preferential treatment or if there is a lack of transparency in decision-making processes [36].

The intersection of educational decisions with ethical considerations can lead to varying interpretations of what is fair and just, contributing to potential conflicts in the relationship between schools and parents. Therefore, fostering open communication, transparency, and mutual respect is essential for building and maintaining positive relationships between these two stakeholders in the educational process [37]. Below, Figure 1 depicts the conditions for successful inclusive education, which stem from the simultaneous emergence of well-established school management of inclusive education for students with SEN and parental collaboration. Deviation from this condition occurs when parents misperceive that their children’s treatment does not meet expected standards and when there is a failure to communicate effectively from the school. This can result in resistance to further collaboration or complete distrust.

Figure 1.

Representation of potential problems and their consequences.

This figure illustrates how the lack of effective communication and collaboration between parents and the school can lead to various negative consequences, including distrust, dissatisfaction, and resistance from parents. These consequences can further impact the implementation of inclusive education initiatives and the overall environment for students, both regular and with SEN. Additionally, it may also result in parents advocating for changes or services that may not be feasible or appropriate for the school to provide.

Ultimately, the aim of this study is to understand the perceptions of parents of students with SEN studying in a small-sized regular school. The study seeks not only to comprehend the existing perceptions of parents but also to propose a strategy to reorient parental perceptions in order to create conditions for successful inclusive education. The main objectives of this study are: (1) to investigate the current perceptions of parents of students with SEN studying in a small-sized regular school toward school management of inclusive education practices, and (2) to identify the key factors contributing to potential misunderstandings between schools and parents regarding the implementation of inclusive education practices for students with SEN in small-sized regular schools.

1.2. Syllogistic Reasoning

In order to carry out the stated objectives and find answers for this study regarding the key factors that cause misunderstandings for parents regarding the management of inclusive education practices at schools for students with SEN, the selection of an approach deemed as the most appropriate way to find the answer was by built around practical syllogism [38].

The concept of practical syllogism originates from the field of philosophy, particularly in the realm of ethics and moral reasoning. It has its roots in the works of ancient Greek philosophers, most notably Aristotle, who extensively discussed syllogistic reasoning in his writings on logic and ethics [39]. Aristotle introduced the notion of syllogism as a form of deductive reasoning consisting of three propositions: a major premise, a minor premise, and a conclusion. Syllogistic reasoning was primarily applied in the domain of theoretical or logical inquiries to draw logical conclusions from given premises [40].

Later, philosophers such as Thomas Aquinas expanded upon Aristotle’s ideas and applied syllogistic reasoning to practical or moral decision-making, giving rise to the concept of practical syllogism. In this context, practical syllogism involves applying ethical principles or moral rules to specific situations to guide moral action or decision-making [41].

Suchanek [42] further developed the concept of practical syllogism within the context of ethical reasoning in business settings. He emphasized the importance of integrating ethical principles with practical considerations to address ethical dilemmas and make morally sound decisions in business practices.

In the context of the study on parental perceptions of schools’ management of inclusive education for students with SEN, practical syllogism can be used as an approach to finding answers by following these steps outlined in Table 1 below:

Table 1.

Practical syllogism structure in the context of parental perceptions of schools’ management of inclusive education for students with SEN.

By employing practical syllogism, the study can systematically analyze ethical dilemmas related to inclusive education and generate practical solutions that are ethically sound and contextually relevant. This approach helps ensure that the findings and recommendations of the study are grounded in both ethical principles and the realities of the specific educational context under investigation.

1.3. Ethical Principles

In the context of inclusive education, a fundamental ethical principle is the promotion of equality, fairness, and respect for diversity. Equality underscores the notion that every student, regardless of their abilities, background, or characteristics, should have equal opportunities to access education and participate fully in the learning process. Fairness in inclusive education refers to the fair treatment of every student, taking into account their individual needs, strengths, and challenges. It involves promoting justice and impartiality in educational practices, decision-making processes, and resource allocation to ensure that each student receives the support and opportunities they require to succeed [2]. On the other hand, respect for diversity highlights the value of recognizing and embracing the unique characteristics, experiences, and perspectives of every student [43,44].

This principle translates to providing equal opportunities for all individuals, regardless of their background, abilities, or differences [45]. Moreover, in the setting of schools and parents, these ethical principles serve as guiding values that inform and shape inclusive education practices, policies, and interactions within the school community [46]. By upholding these principles, educators, administrators, and stakeholders can foster a culture of inclusivity, equity, and respect that supports the holistic development and success of every student while simultaneously building trust relationships and reducing conflicts, i.e., avoiding deviation as a result of misperception and miscommunication [47,48].

1.4. Possible Misperceptions

Parental misperceptions of ideal practices of inclusive education rendered by schools can stem from various factors such as lack of clear communication between schools and parents regarding inclusive education policies, practices, and goals. When schools fail to effectively communicate their approach to inclusive education or provide updates on their efforts to accommodate students with SEN, parents may develop misperceptions or misunderstandings about the school’s commitment to inclusive practices [25]. In addition, these parental misperceptions may arise due to limited access to information or resources about inclusive education, especially when they are not adequately informed about the benefits of inclusive education or the strategies employed by schools to support students with SEN, they may rely on misconceptions or stereotypes about special education programs. This lack of awareness can lead to unrealistic expectations or concerns about the quality of education provided to their children [36].

In some settings, cultural or societal beliefs about disability and inclusion play crucial roles that can also influence parental perceptions of ideal practices in inclusive education. In some cultures, there may be stigma or misconceptions surrounding disabilities, leading parents to hold biased or negative views about inclusive education. These preconceived notions can hinder parents’ ability to fully support inclusive practices and collaborate effectively with schools [49].

Past experiences or interactions with schools may also shape parental perceptions of inclusive education. If parents have encountered barriers or challenges when advocating for their child’s inclusion in the past, they may be more skeptical or resistant to inclusive practices in their current educational setting. Conversely, positive experiences with inclusive education initiatives may foster greater trust and confidence in the school’s approach among parents [50].

In addition, numerous studies have identified circumstances that can lead to misunderstandings between schools and parents. Some highlights include the following.

de Boer, Pijl, and Minnaert [51] reported that one of the main concerns of parents of children with SEN is that their children would not have sufficient opportunities to participate in peer groups when studying in a regular school.

Göransson and Nilholm [52] analyzed research on inclusive education and found that there are four areas of potential misunderstanding regarding inclusive education being practiced in schools: (1) the placement of SEN students in regular classrooms, (2) provisions to meet the social and academic needs of SEN students, (3) provisions to meet the social and economic needs of all students, and (4) the inclusion of the creation of communities.

As Lindner et al. [53] examined the potential for promoting an inclusive process involving different actors—teachers, students, and parents, with or without SEN students—the findings revealed that sustainable inclusive development requires support at all levels from all stakeholders involved. Previous research has shown that parents of SEN children are more inclined toward inclusive education and perceive positive social effects and advantages for all students, compared to parents of children without SEN. In addition, parents of children without SEN tend to exhibit neutral attitudes toward inclusion [54]. Moreover, parents are more open to the inclusion of students with physical learning disabilities than those with behavioral disorders or intellectual disabilities [24].

Furthermore, engaging with parents to understand their views and needs would assist them in supporting their children, reflecting an approach that serves as a first step in creating more equitable partnerships between parents of children with SEN and professionals [55]. These findings offer crucial perspectives for social participation from various actors, thereby ensuring that the management of inclusive education caters to all needs [54]. Despite research on inclusive education primarily focusing on teachers’ attitudes, studies on parents’ attitudes or perceptions toward inclusive education remain scarce [24]. Thus, attention should be directed toward understanding parents’ perceptions of special education management in inclusive education [53].

To gain a better understanding of parents’ perceptions regarding special education management in inclusive settings, the research team opted for a single case study approach. This case study aims to illuminate the development of inclusive communities within regular schools, shedding light on the social processes and theoretical concepts at play [56]. Employing qualitative research methods for data collection, the study addresses the following research questions: (a) How do parents of students with SEN perceive the inclusive setting? and (b) Are there any variations in opinions among parents from different backgrounds? The insights gleaned from this investigation will prove invaluable for schools and educational institutions seeking to enhance inclusive education, thereby providing better support and opportunities for students with SEN within inclusive settings.

Insights obtained from the results of this study are particularly important as they contribute to the existing body of knowledge regarding perceptions that act as barriers to successful inclusive education. Furthermore, these insights enable the formulation of strategies to overcome these barriers. The goal is to achieve comprehensive and sustainable inclusive education in a thorough manner.

1.5. Unique Characteristics of Small-Sized Schools

Small-sized schools often possess unique characteristics that differentiate them from larger educational institutions. These characteristics can significantly impact the learning environment and the well-being of students. Consequently, parents of students attending small-sized schools may harbor negative perceptions, which may not always align with reality. When such misperceptions arise, they can undermine the progress of small-sized schools in creating conditions for successful inclusive education, potentially leading to unsuccessful management of inclusive education practices. These characteristics and reasons include:

- Limited resources—Small-sized schools typically have fewer financial resources and physical facilities compared to larger educational institutions. This limitation can hinder the maximization of teaching materials in several ways. For instance, small-sized schools may have a smaller budget allocated for purchasing teaching resources such as textbooks, educational tools, and technology equipment. As a result, parents may perceive that teachers may have limited access to a variety of materials needed to enhance the learning experience for students [24,50].

- Unclear guidelines on the assessment system—Ambiguities in the guidelines related to the assessment system can lead to challenges and inconsistencies in teaching and learning experiences within small-sized schools. The absence of clear direction on what and how to assess may cause parents to perceive that teachers might resort to generic or standardized assessments that inadequately measure students’ mastery of intended learning outcomes. This can result in substandard learning experiences. Parents of children with SEN, in particular, anticipate more attention and clarity regarding the assessment system [57,58]. When this misperception occurs, the impact is further magnified.

- The lack of specialized staff with sufficient background in caring for students with SEN—Specialized staff, such as special education teachers or support personnel, are crucial for providing individualized support to students with SEN. Without these professionals, parents are likely to perceive that small-sized schools may struggle to meet the unique requirements of students with SEN, hindering their educational progress [59,60,61].

- Limited understanding of inclusive education—Among parents, especially those with SEN, misunderstanding regarding inclusive education practices about how their children will be treated in regular schools causes concerns. Parents may harbor concerns about whether their children will receive appropriate support, accommodations, and acceptance within the school environment [25]. These concerns can impact parental perception s of the school’s ability to effectively manage inclusive education practices and may lead to apprehension or resistance toward inclusive schooling for their children [62].

- Anxiety about pushback from parents of regular students—Most parents who send their children to small-sized schools, which undoubtedly differ from larger schools, naturally harbor concerns about their children’s competitiveness, whether it pertains to advancing to higher educational levels or securing good employment opportunities later on [63]. This concern is particularly heightened among parents with children who have SEN. If the school fails to address this issue adequately, it may lead to parental views about the likelihood of opposition from parents of regular students. Consequently, parents with such perceptions may refrain from participating, disregard the school’s decisions regarding the direction of their children’s education, or, in extreme cases, opt to withdraw their children from school altogether [64].

- Lack of clear policies and preventative measures against bullying and emotional isolation [65]. The misperception about this topic can erode confidence in the school’s ability to provide a supportive and inclusive environment for all students. As a result, parents may become more cautious about sending their children to the school or may advocate for alternative educational options that they perceive as safer and more accommodating. In addition, if parents misunderstand the practices implemented by the school, they may lack confidence in the school’s ability to meet the needs of their children with SEN. This lack of confidence can lead to decreased parental involvement and collaboration with the school, hindering the development of a supportive and inclusive learning environment [62].

- Limitation regarding infrastructure—The physical environment, including inadequate facilities and a learning environment that lacks support facilities for students as well as teachers, poses concerns that are commonly seen among parents of students in small-sized schools. This particular issue arises from the belief that small-sized schools are not well equipped to facilitate learning in a diverse classroom [60].

These are some of the issues raised to provide an idea of how small-sized schools may create certain perceptions due to their special characteristics for parents. In some cases, this can affect their confidence and desire to participate in creating a relationship of mutual trust (invest in trust) between schools and parents. In addition, these special characteristics have been translated into research tools, as provided in the next section, to understand parents’ perceptions.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

For the design of this study, a non-experimental approach was employed, utilizing a predominantly qualitative research method, supplemented by some inferential statistical analysis in specific areas such as socio-economic identification and educational background. This approach aimed to gain insight into the backgrounds of the participants.

A structured survey questionnaire, developed by the researchers, served as the primary research instrument. It consisted of three sections: the first section collected background information about the participants, while the second section contained items aimed at exploring parents’ perceptions of the unique characteristics of small-sized schools that could influence their actions toward school management of inclusive education practices. This section included both closed and open-ended questions. The third section allowed participants to freely express their thoughts on any particular topic of interest. This design is similar to the approach used in research by Dimitrova-Radojchich and Chichevska-Jovanova in 2014 [66], which focused on parents’ attitudes toward inclusive education for children with disabilities.

Please note that for this study conducted in Indonesia, the instrument was initially prepared in English and sent to the Indonesian collaborating partner for translation into Bahasa Indonesia for use in interviewing parents. Subsequently, the results of the interviews were translated back into English to facilitate their incorporation into research reports and articles.

2.2. Sampling

The purposive sampling technique was used to obtain samples, drawn from parents of students with SEN on a voluntary basis, in a regular small-sized school where both regular students and students with SEN are enrolled in a classroom where both students with and without SEN study together, used as a case study. In addition, the school is reported to be well prepared for inclusive teaching, with a budget allocated sufficient to cater to classroom needs and adequately prepared personnel and support systems.

After the details of this study were explained, participants were informed of their right to stop or withdraw consent at any time, regardless of the stage. Once participants had agreed and provided written consent to the researchers, the interviewer proceeded with reading the questions. Participants were asked to select the options that corresponded best with their reality in Section 1. In Section 2, they were instructed to rate their responses based on their own judgment using a 5-point Likert rating scale questionnaire: 1 = strongly disagree (X̄ = 1.00–1.50), 2 = disagree (X̄ = 1.51–2.50), 3 = not certain (X̄ = 2.51–3.50), 4 = agree (X̄ = 3.51–4.50), and 5 = strongly agree (X̄ = 4.50–5.00). Finally, participants were invited to express their thoughts on their perceptions concerning the management of inclusive practices by the school based on their views and experiences, and they were encouraged to provide feedback or freely express their thoughts in Section 3.

2.3. Data Analysis

The collected data from the five-point rating scale survey questionnaire were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23.0 to compute the mean, standard deviation, and percentage. Additionally, the data obtained from the unstructured interviews were analyzed through content analysis, which involved collating relevant data for each theme. Subsequently, clear definitions were generated for each theme, and a report on the analysis was produced [67].

2.4. Reliability

The questionnaire’s internal reliability was measured at 0.688 using Cronbach’s Alpha. The second section comprised both closed and open-ended questions aimed at exploring barriers to inclusion. These questions were informed by previous discussions and drew on established literature. Notable works include Forlin’s 2010 [4] research, which emphasizes the need for reform in teacher education to better prepare teachers for inclusion. Florian’s 2011 [68] work focuses on inclusive education and the challenges and opportunities it presents in supporting students with disabilities. Loreman’s 2010 [8] research highlights the necessary outcomes for pre-service teachers in Alberta to effectively engage in inclusive education practices. Ainscow and Sandill’s 2010 [18] work delves into the role of organizational culture in the development of inclusive education systems. Lastly, Page et al.’s 2019 [69] research focuses on specific aspects, such as outcomes for pre-service teachers or the attitudes of parents toward inclusive education for children with disabilities.

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

The study was conducted in a small-sized school located in Surabaya, Indonesia. A total of 53 parents volunteered to participate in the study. Their children had various disabilities, including learning disabilities, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, hearing impairment, Down syndrome, and multiple disabilities. Regarding the educational backgrounds of the parents, 4 had lower secondary education (7.5%), 18 had higher secondary education (41.5%), 2 had vocational education (3.8%), 6 had a diploma (11.3%), 20 had a bachelor’s degree (37.7%), and 3 had a master’s degree (5.7%). Table 1 below shows the overall characteristics of participants based on their educational backgrounds. Table 2 displays the characteristics of participants according to their educational backgrounds.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants based on their educational backgrounds.

3.2. Parents’ Perception

In Section 2, participants were asked to assess their responses using a five-point Likert rating scale questionnaire. This scale ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), allowing participants to express their level of agreement or disagreement with each statement. The mean values (X̄) associated with each rating range provided further insight into the distribution of responses, with lower mean values indicating stronger disagreement and higher mean values indicating stronger agreement.

The provided Table 3 below encapsulates the responses of participants concerning various statements that delve into the inclusion of children with SEN in regular school classrooms. Each statement is accompanied by mean (X̄) and standard deviation (S.D.) values, which represent the average rating given by the respondents and the extent of variability in their responses, respectively. The summary of responses and explanations based on Table 3 are as follows:

- Children with disabilities should be included in regular classrooms (X̄ = 3.81, S.D. = 1.00): The mean value suggests a moderate level of agreement among participants, indicating an inclination toward the idea of inclusive classrooms.

- Children with disabilities cause problems and are a burden for the school children (X̄ = 3.64, S.D. = 0.79): Respondents, on average, displayed a moderate level of disagreement with this statement, suggesting a more positive attitude toward the role of children with disabilities in regular school settings.

- Children with disabilities benefit from regular school children (X̄ = 4.15, S.D. = 0.60): This statement received a higher mean, indicating a general consensus among participants that children with disabilities derive benefits from interacting with their regular peers.

- Regular school children gain benefit in social adjustment when studying with children with disabilities (X̄ = 3.85, S.D. = 0.60): Participants expressed a moderate level of agreement, suggesting a belief that inclusive settings positively influence the social adjustment of all children.

- Children with disabilities strengthen their social skills when studying with regular children (X̄ = 4.13, S.D. = 0.59): The higher mean suggests a general consensus among participants that inclusive environments contribute positively to the social skills development of children with disabilities.

- Inclusive school classrooms support development for children with disabilities only (X̄ = 3.08, S.D. = 1.02): This statement received a lower mean, indicating a tendency for participants to disagree with the notion that inclusive settings exclusively benefit children with disabilities.

- Children with disabilities should attend special education school (X̄ = 2.51, S.D. = 0.97): Respondents exhibited a lower level of agreement, suggesting a preference for inclusive education over special education settings for children with disabilities.

- Children with disabilities in regular school will be left out (nobody pays attention to them) (X̄ = 3.70, S.D. = 1.17): The mean suggests a moderate level of disagreement, indicating that participants do not strongly believe that children with disabilities would be neglected in regular schools.

- Regular school will lead children with disabilities to have lower self-esteem (X̄ = 3.68, S.D. = 0.96): Participants, on average, displayed a moderate level of disagreement, suggesting a belief that inclusive settings do not necessarily result in lower self-esteem for children with disabilities.

- Regular school children should have plans to help children with disabilities learn with regular students (X̄ = 3.64, S.D. = 0.68): The mean indicates a moderate level of agreement, reflecting a general sentiment among participants that proactive plans for inclusive education are beneficial.

- If children with disabilities join an inclusive classroom, teachers have to spend too much time with them, affecting the learning opportunities of regular students (X̄ = 3.58, S.D. = 0.75): Respondents, on average, displayed a moderate level of disagreement, suggesting a belief that inclusive education does not excessively burden teachers or hinder the learning opportunities of regular students.

- It is necessary for an organization to arrange a training program for personnel in regular schools so teachers can help children with disabilities (X̄ = 4.45, S.D. = 0.50): The higher mean indicates a strong agreement among participants, emphasizing the perceived importance of training programs to equip teachers for inclusive education.

- Children with disabilities should accept their fate by not being a burden for school (X̄ = 3.53, S.D. = 0.93): Participants exhibited a moderate level of disagreement, indicating a reluctance to endorse the idea that children with disabilities should accept their fate without being accommodated in school.

- If an organization provides learning materials and trained teachers for children with disabilities in school, our regular children should gain better development (X̄ = 4.40, S.D. = 0.69): The higher mean reflects a strong agreement among participants, underlining the belief that inclusive measures benefit the development of all school children.

Table 3.

Summary of parents’ perceptions about inclusive education practices.

Table 3.

Summary of parents’ perceptions about inclusive education practices.

| Issues | X̄ | S.D. |

|---|---|---|

| Children with disabilities should be included in regular classrooms. | 3.81 | 1.00 |

| Children with disabilities cause problems and are a burden for the regular school children. | 3.64 | 0.79 |

| Children with disabilities benefit from regular school children. | 4.15 | 0.60 |

| Regular school children gain benefit in social adjustment when studying with children with disabilities. | 3.85 | 0.60 |

| Children with disabilities strengthen their social skills when studying with regular children. | 4.13 | 0.59 |

| Inclusive school classrooms support development for children with disabilities only. | 3.08 | 1.02 |

| Children with disabilities should attend special education school. | 2.51 | 0.97 |

| Children with disabilities in regular school will be left out (nobody pays attention to them). | 3.70 | 1.17 |

| Regular school will lead children with disabilities to have a lower self-esteem. | 3.68 | 0.96 |

| Regular school children should have plans to help children with disabilities to learn with regular students. | 3.64 | 0.68 |

| If children with disabilities join an inclusive classroom, teachers have to spend too much time with them, which would affect the learning opportunities of regular students. | 3.58 | 0.75 |

| It is necessary for an organization to arrange a training program for personnel in regular schools, so teachers can help children with disabilities. | 4.45 | 0.50 |

| Children with disabilities should accept their fate by not being a burden for school. | 3.53 | 0.93 |

| If an organization such as a municipality or local government organization provides learning materials and trained teachers to help children with disabilities in school, our regular children should gain better development as well. | 4.40 | 0.69 |

In essence, the table serves as a detailed snapshot of the various perceptions held by participants regarding inclusive education practices. It offers valuable insights into the spectrum of opinions, ranging from areas of unanimous agreement to points of divergence among parents regarding the integration of children with disabilities into regular school environments. This comprehensive overview sheds light on the complex landscape of attitudes toward inclusive education, highlighting the nuances and intricacies inherent in navigating the inclusion of diverse learners in educational settings.

3.3. Open-Ended Questionnaire Insights

Based on the analysis of the open-ended questionnaire responses, three main themes emerged, revolving around the perceptions of parents, teachers, and the school environment. It was observed that parents with a lower secondary education background displayed a lack of clear understanding regarding the concept of inclusive education, as evidenced by their responses, which were often rated at uncertain levels. For instance, a parent of a child with multiple disabilities expressed concerns about their child’s potential for independence in a regular classroom, questioning how much support they would receive from teachers. They stated,

“I expect my child with special needs to learn to be independent, but I’m uncertain about how much support he can receive in a regular classroom. The regular teacher may not have sufficient time to provide the necessary training.”

Similarly, another parent of a child with autism highlighted the importance of teacher competence in inclusive classrooms, stating, “While I support the idea of learning in a regular classroom, I believe it’s essential for teachers to possess the necessary skills to effectively teach students with special needs”.

As for the other two parents with a background in lower secondary education, they expressed satisfaction with the school setting. One parent has a child with hydrocephalus, a brain condition involving fluid buildup, while the other has a child with high-functioning autism. One parent commented, “When sending a child with SEN to an inclusive school, parents must understand their child’s abilities to provide optimal support and meet their needs for development”. The other parent remarked, “In an inclusive classroom, SEN students don’t require excessive attention from the teacher”.

Some parents expressed support for having students with SEN in regular classrooms, as evidenced by positive perceptions on teachers’ knowledge and skills, the learning environment, and leadership. Their explanations during the interviews fell under these same themes. Here are some examples of their opinions.

On the issue of the learning environment: “When SEN students are in a regular classroom, they can socialize with regular students”. “Even though SEN students may seem unable to do things by themselves, they have the potential to learn within the classroom setting”. “The school environment doesn’t make children feel different from each other because the school creates a classroom where the children have a positive attitude towards SEN students”. “The school provides additional hours of therapy for children who need specific treatment”.

On the issue of teachers’ knowledge and skills: “Teachers pay attention to SEN students. They place learners according to their ability. The teachers understand the competence of the children”. “Teachers care about SEN students”.

However, there are also several concerns raised about the skill development of teachers. Parents express apprehension regarding the teachers’ knowledge and abilities to assist SEN students. Their viewpoints included: “The teachers lack sufficient skills to support SEN students”. They also suggested that “more shadow teachers are needed to assist regular teachers”. Some parents worried that “SEN students may disrupt the classroom if teachers lack the necessary skills to manage such situations”. They advocated for “improved training in academic and support skills for teachers to enhance their quality”. Furthermore, they emphasized the necessity for “training teachers adequately to manage an inclusive classroom”. Lastly, there was a call for “expert support to aid in the development of SEN students”.

Some parents expressed their appreciation for the presence of shadow teachers who assist in caring for SEN students in the classroom. “Shadow teachers are effective in looking after our children. The school should consider hiring more shadow teachers so that there is assistance available when teachers are occupied”.

As for the issue of leadership, parents did not extensively share their opinions on the school principal. One positive aspect highlighted by parents was, “The school-community relationship is well-established, allowing teachers and parents to communicate effectively”. However, some suggestions and comments were also provided, such as, “The principal should focus on the inclusion program within the school, as teachers may not have the authority to make decisions regarding support for SEN students; the principal should take the lead in decision-making”.

Some important messages emerged during the interviews, such as, “The school should focus on reducing instances of bullying, enhancing infrastructure for SEN students, and ensuring teachers have a deeper understanding of the children’s conditions”. These points were emphasized by a parent of a child with Down syndrome.

In terms of infrastructure, a parent of a child with a hearing impairment and ADHD commented that “there should be adequate facilities for SEN students”. Another suggestion was made related to tuition fees: “When schools accept SEN students at a lower cost, all children will have access to education, so SEN should be included in regular schools”.

In conclusion, the insights derived from the open-ended questionnaire analysis shed light on various dimensions of parents’ perceptions on inclusive education practices in the small-sized school setting. While many parents expressed support for the inclusion of students with SEN in regular classrooms, concerns were raised regarding teachers’ knowledge and skills in handling SEN students. The importance of infrastructure, leadership involvement, and efforts to reduce bullying were emphasized as critical elements for creating an inclusive and supportive learning environment. The diverse viewpoints presented by parents underscore the need for ongoing collaboration between schools and parents to address these concerns and enhance the effectiveness of inclusive education practices in small-sized schools.

4. Limitations of This Study

It is essential to acknowledge the limitations of this study. The research employed a case study approach and utilized purposive sampling to collect data from the survey. Consequently, due to the nature of the non-probability sampling method, the findings may not precisely represent the entire population of the country and cannot be generalized to the broader population, except for units of analysis with comparable characteristics. In addition, any biases observed in the findings may arise from the sampling approach itself rather than being intentional aspects of the study. Moreover, the translated questionnaire, presented in English, may not perfectly align with how it was addressed in Bahasa in the real context.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Based on the empirical findings, it is revealed that the major premise—shared value agreed upon by both the school and parents as an ideal mutual benefit, fostering a resistance-free relationship—is that all students, irrespective of their abilities, deserve equal opportunities for education and inclusion. This principle underscores the values of equality, fairness, and respect for diversity in education.

In reality, the minor premise reveals that there are still hindrances preventing schools from upholding the shared value agreed upon by both parties (major premise). These obstacles arise from various factors, including the legacy system in place that does not fully support the implementation of the school’s approach to inclusion, the challenges posed by students with SEN themselves, and the concerns or misconceptions of parents regarding the efficacy of inclusive practices due to poor communication.

Integrating both premises, the conclusion drawn from the ethical principle of equality and fairness in education is to implement strategies aimed at addressing parental concerns and enhancing the inclusivity of small-sized regular schools. This may entail providing additional support and resources for students with SEN, improving teacher training on inclusive practices, and fostering better communication between schools and parents to ensure the needs of all students are met. Table 4 below illustrates the practical syllogism structure based on research findings.

Table 4.

Practical syllogism structure based on empirical findings.

Based on the conclusion drawn from the study, actionable strategies can be developed to improve parents’ perceptions regarding the management of inclusive education practices for students with SEN in small-sized regular schools. Table 5 illustrates some sample of actionable strategies elaborated based on the conclusion from the practical syllogism structure include the following.

Table 5.

Sample of actionable strategies.

Next, based on the empirical findings, the parents’ overall perception suggested a predominantly positive outlook, especially regarding the advantages of having SEN students in a regular school, the improvement of social skills for SEN students in inclusive classrooms, and the positive influence on regular students. These aspects received high ratings (X̄ = 3.72, S.D. = 0.36) from the parents. This finding is consistent with prior research indicating a generally favorable attitude among parents toward inclusive education [51].

However, the item “SEN students should attend a special school” received an uncertain rating level. This suggests that some parents may lack a clear understanding of an inclusive setting but are more familiar with the concept of special education. This observation aligns with Yusuf et al.’s (2014) [61] findings that some parents do not have a clear understanding of inclusive education. Conversely, this study revealed that parents with higher educational backgrounds seemed to have a clearer grasp of an inclusive setting, as indicated by their higher agreement rate with the concept of an inclusive school. For parents who do not fully comprehend the meaning of inclusive education, concerns persist about how their children will be treated in regular schools.

Moreover, the above-mentioned finding was supported by the opinions of parents with a background in lower secondary education. They expressed concerns that their children might not receive enough help from teachers in a regular classroom due to the high number of students, whereas in a special education school, teachers exclusively focus on SEN students. This perception could stem from their familiarity with the special education school system, where they may believe that SEN students receive more personalized attention compared to an inclusive classroom. It is possible that inclusive education is a relatively new concept to them, as indicated in the studies by Poernomo (2016) [60] and Yusuf (2014) [61].

The most notable concern expressed by parents revolves around the perceived lack of teacher skills in assisting SEN students, a recurring issue in discussions on inclusive settings [4,8,20,69,70]. A significant finding in this study is the emphasis placed by parents of students with Down syndrome on the need for the school to address bullying. This underscores that, despite the majority of parents having a positive attitude toward including SEN students in regular schools, challenges persist within the school environment. This observation resonates with a Swedish case study survey, which reported that students with disabilities seldom or never had fun with friends and were vulnerable to bullying [71]. Previous research has also pointed out environmental and attitude barriers [64], indicating the presence of inclusion obstacles within the school.

This situation resonates with Göransson and Nilholm’s (2014) [52] assertion that a crucial aspect of research on inclusive education is for schools to strive toward creating cohesive communities. Facilitating communication between the school and the community can foster a deeper understanding of inclusive environments and mitigate barriers to inclusion. Lim and Cho (2019) [72] have highlighted that, in the modern era, mobile documentation offers an interactive means of communication between home and school. Given the significance of bullying and environmental concerns in this case study, leveraging mobile documentation could be a viable strategy to promote a positive atmosphere and enhance understanding of inclusive classrooms.

6. Concluding Remarks

This study discovered that parents of SEN students generally maintain a positive outlook toward inclusive education, with no notable disparities in perceptions observed among parents with varying educational backgrounds. Participants commonly expressed concerns regarding teachers’ proficiency in supporting SEN students and emphasized the importance of tackling bullying. However, certain areas may necessitate additional attention, particularly the enhancement of teachers’ knowledge and skills.

Some strategies recommended by Nel et al. (2014) [73] for implementing inclusive education involve establishing a district-based support team to aid teachers working in inclusive settings. This team may include professionals such as psychologists, counselors, therapists, and other health welfare workers. Implementing this proposal could help address current gaps and serve as an initial step toward fostering an inclusive environment within schools and classrooms. Additionally, such a support system could facilitate the provision of learning materials tailored to the educational needs of SEN students, especially those requiring specialized assistance.

Moreover, higher educational institutions should collaborate with schools to enhance teacher development, as the literature indicates that teachers’ attitudes and skills in inclusive/special education are crucial for successful inclusion. This case study is not exhaustive; it merely presents the current situation in an inclusive setting. Building on the findings from this study, future research should explore several issues: (1) the delivery of support services by various community resources and institutes, (2) identifying key functions to assist schools in addressing barriers to learning and fostering an inclusive environment, (3) investigating the attitudes of parents of regular students and regular students themselves toward inclusive education, (4) examining the contributions from local education and administrative support, and (5) exploring appropriate approaches for disseminating knowledge to parents about inclusive education.

Finally, based on the findings from this case study, future research should explore the following issues: the delivery of support services by various resources and institutes in the communities, identification of key functions to assist schools in addressing barriers to learning and establishing an inclusive environment, exploration of the attitudes of parents of regular students and regular students themselves toward inclusive education, contribution from local education and administrative support, investigation of appropriate approaches for the distribution and sharing of knowledge to parents concerning inclusive education, and consideration of alternative models such as mainstream education with separate support for severe cases of SEN students, which may provide reassurance to parents concerned about their children receiving adequate assistance beyond inclusive classrooms alone. These are possible areas for future research and policy development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.N. and N.K.; Methodology, P.N. and N.K.; Validation, N.K.; Formal analysis, P.N. and N.K.; Investigation, P.N. and N.K.; Data curation, P.N. and N.K.; Writing—original draft, P.N. and N.K.; Writing—review & editing, P.N. and N.K.; Project administration, P.N. and N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were not applicable due to this study was conducted in early 2019, predating the enforcement of the ‘Khon Kaen University Regulations on Human Research Requirements 2020’. Hence, actions taken before the regulation’s announcement cannot be retrospectively enforced. Additionally, since approval could only be granted before the study commenced, retrospective approval is impossible.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors claim no conflict of interest.

References

- Peters, S.J. Inclusive Education: An EFA Strategy for All Children; World Bank, Human Development Network: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. In Proceedings of the Adopted by the World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality, Salamanca, Spain, 7–10 June 1994; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. The Right of Children with Disabilities to Education; UNICEF Regional Office for Central and Eastern Europe and Commonwealth of Independent States (CEECIS): Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Forlin, C. Re-framing teacher education for inclusion. In Teacher Education for Inclusion: Changing Paradigm and Innovative Approaches; Forlin, C., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Forlin, C.; Lian, M.-G.J. (Eds.) Contemporary trends and issues in education, reform for special and inclusive education in the Asia-Pacific region. In Reform, Inclusion and Teacher Education: Towards a New Era of Special Education in the Asia-Pacific Region; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2008; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Breyer, C.; Lederer, J.; Gasteiger-Klicpeera, B. Learning and support of assistants in inclusive education: A transitional analysis of assistance services in Europe. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2020, 36, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M.; Booth, T.; Dyson, A. Improving Schools, Developing Inclusion; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Loreman, T. Essential inclusive education-related outcomes for Alberta preservice teachers. Alta. J. Educ. Res. 2010, 56, 124–142. [Google Scholar]

- Forlin, C. (Ed.) Responding to the need for inclusive teacher education. In Future Directions for Inclusive Teacher Education: An International Perspective; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ainscow, M.; Haile-Giorgis, M. Educational arrangements for children categorized as sharing special needs in Central and Eastern Europe. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2006, 14, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, E.; Nel, N. What counts as inclusion? Afr. Educ. Rev. 2012, 9, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, I.; Woodcock, S. Contesting the recognition of Specific Learning Disabilities in educational policy: Intra- and inter-national insights. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2014, 66, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulholland, M.; O’Connor, U. Collaborative classroom practice for inclusion: Perspectives of classroom teachers and learning support/resource teachers. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2016, 20, 1070–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlin, C. (Ed.) Diversity and its challenges for teachers. In Future Directions for Inclusive Teacher Education: An International Perspective; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012; pp. 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kantavong, P. A training model for enhancing the learning capacity of students with special need in inclusive classrooms in Thailand. In Future Direction for Inclusive Teacher Education: An International Perspective; Forlin, C., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012; pp. 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kantavong, P. Understanding inclusive education practices in schools under local government jurisdiction: A study of Khon Kaen Municipality in Thailand. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2017, 22, 767–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Noman, M.; Awang-Hashim, R. Exploring strategies of teaching and classroom practices in response to challenges of inclusion in a Thai school: A case study. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2016, 20, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M.; Sandill, A. Developing inclusive education systems: The role of organizational cultures and leadership. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2010, 14, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Martin, S.M. Assessing the needs of training on inclusive education for public school administrators. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2015, 19, 1229–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U.; Forlin, C.; Deppeler, J. Reforming Teacher Education for Inclusion in Developing Countries in the Asia-Pacific Region. Asian J. Incl. Educ. 2013, 1, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, L.; Linklater, H. Preparing teachers for inclusive education: Using inclusive pedagogy to enhance teaching and learning for all. Camb. J. Educ. 2010, 40, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rege, K.; Almeida, N. Effective communication facilitates partnering with parents: Perception of supervisors and teachers at preschool and primary school levels. OIDA Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 6, 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Nurse, L. Parental perception of inclusive education: Mothers’ narrative construct of the school space. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paseka, A.; Schwab, S. Parents’ attitudes towards inclusive education and their perceptions of inclusive teaching practices and resources. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2020, 35, 254–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swart, E.; Engelbrecht, P.; Eloff, I.; Pettipher, R.; Oswald, M. Developing inclusive school communities: Voices of parents of children with disabilities. Educ. Chang. 2004, 8, 80–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Berry, L.L.; Zeithaml, V.A. Perceived service quality as a customer-based performance measure: An empirical examination of organizational barriers using an extended service quality model. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1991, 30, 335–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambe, C.J.; Spekman, R.E.; Hunt, S.D. Alliance competence, resources, and alliance success: Conceptualization, measurement, and initial test. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2002, 30, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, D. Individuals, Interpersonal Relations, and Trust. In Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations, Electronic Edition; Gambetta, D., Ed.; Department of Sociology, University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 31–48, Chapter 3; Available online: https://philarchive.org/rec/GAMTMA (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Spann, S.J.; Kohler, F.W.; Soenksen, D. Examining parents’ involvement in and perceptions of special education services: An interview with families in a parent support group. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2003, 18, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennis, W.M.; Medin, D.L.; Bartels, D.M. The Costs and Benefits of Calculation and Moral Rules. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 5, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verger, A.; Moschetti, M. Education Policy Approach: Multiple Meanings, Risks and Challenges. Educ. Res. Foresight Work. Pap. 2017, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mendez, J.B.; Quark, A.A. Debating Equity through Integration: School Officials’ Decision-Making and Community Advocacy During a School Rezoning in Williamsburg, Virginia. Crit. Sociol. 2023, 49, 749–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousholt, D.; Juhl, P. Addressing Ethical Dilemmas in Research with Young Children and Families. Situated Ethics in Collaborative Research. Hum. Arenas 2023, 6, 560–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornby, G.; Lafaele, R. Barriers to parental involvement in education: An explanatory model. Educ. Rev. 2011, 63, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Zhu, X. Special education reform towards inclusive education: Blurring or expanding boundaries of special and regular education in China. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2016, 16, 994–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teise, K. Creating safe and well-organised multicultural school environments in South Africa through restorative discipline. Int. J. Educ. Sci. 2016, 13, 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, A. The Practical Syllogism and Incontinence 1. Phronesis 1966, 11, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, M.T. Aristotelian practical reason. Mind 1982, 91, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, A.R. The Practical Syllogism and Deliberation in Aristotle’s Causal Theory of Action. New Sch. 1981, 55, 281–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westberg, D. Right Practical Reason: Aristotle, Action, and Prudence in Aquinas; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Suchanek, A. Unternehmensethik. In Vertrauen Investieren; Mohr Siebeck: Tübingen, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Osttveit, S. Ten years after Jomtien. Prospects 2000, 30, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoninis, M.; April, D.; Barakat, B.; Bella, N.; D’addio, A.C.; Eck, M.; Endrizzi, F.; Joshi, P.; Kubacka, K.; McWilliam, A.; et al. All means all: An introduction to the 2020 Global Education Monitoring Report on inclusion. Prospects 2020, 49, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNESCO. Education for All 2000 Assessment: Global Synthesis; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- World Declaration on Education for All and Framework for Action to Meet Basic Learning Needs. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Education for All, & Meeting Basic Learning Needs, Jomtien, Thailand, 5–9 March 1990; Inter-Agency Commission: New York, NY, USA, 1990.

- Lawson, H.A. Pursuing and Securing Collaboration to Improve Results. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2003, 105, 45–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyudi, M.; Rugaiyah, R. Inclusive education: Cooperation between class teachers, special teachers, parents to optimize development of special needs childrens. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Stud. 2019, 1, 396–399. [Google Scholar]

- Kervick, C. Parents are the experts: Understanding parent knowledge and the strategies they use to foster collaboration with special education teams. J. Am. Acad. Spec. Educ. Prof. 2017, 62, 82. [Google Scholar]

- Kiling, I.Y.; Due, C.; Li, D.E.; Turnbull, D. A community model for supporting children with disabilities in Indonesia. Disabil. Soc. 2022, 37, 1523–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, A.; Pijl, S.J.; Minnaert, A. Attitudes of parents towards inclusive education: A review of the literature. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2010, 25, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göransson, K.; Nilholm, C. Conceptual diversities and empirical shortcomings—A critical analysis of research on inclusive education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2014, 29, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, K.-T.; Hassani, S.; Schwab, S.; Gerdenitsch, C.; Kopp-Sixt, S.; Holzinger, A. Promoting Factors of Social Inclusion of Students With Special Educational Needs: Perspectives of Parents, Teachers, and Students. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 773230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Krivec, K.; Bastič, M. Attitudes of Slovenian parents towards pre-school inclusion. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2020, 35, 696–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, R.S.; Molina, A.M.; Kozleski, E.B. Until somebody hears me: Parent voice and advocacy in special educational decision making. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 2006, 33, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Black-Hawkins, K. The Framework for Participation: A research tool for exploring the relationship between achievement and inclusion in schools. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2010, 33, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, J. Inclusive schooling: If it’s so good—Why is it so hard to sell? Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2015, 19, 530–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amka, A. Problems and challenges in the implementation of inclusive education in Indonesia. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2017, 7, 159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Poernomo, B. The implementation of inclusive education in Indonesia: Current problems and challenges. Am. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 5, 144–150. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, M.; Rachman, M. The development of inclusive education management model to improve principals and teachers’ performance in elementary schools. J. Educ. Dev. 2014, 2, 154–162. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, C. Experiencing an ‘inclusive’ education: Parents and their children with ‘special educational needs’. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2007, 28, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D. Child and parental mental health as correlates of school non-attendance and school refusal in children on the autism spectrum. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 3353–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmitadila; Widyasari; Prasetyo, T.; Rachmadtullah, R.; Nuraene, Y. The perception of parents toward inclusive education: Case study in Indonesia. People Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 62–79. [Google Scholar]

- Aubé, B.; Follenfant, A.; Goudeau, S.; Derguy, C. Public stigma of autism spectrum disorder at school: Implicit attitudes matter. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 51, 1584–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrova-Radojchich, D.B.; Chichevska-Jovanova, N. Parents attitude: Inclusive education of children with disability. Int. J. Cogn. Res. Sci. Eng. Educ. 2014, 2, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florian, L. Introduction: Mapping international developments in teacher education for inclusion. Prospects 2011, 41, 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.; Boyle, C.; McKay, K.; Mavropoulou, S. Teacher perspectives of inclusive education in the Cook Islands. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2019, 47, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U.; Michael, S. Parental Perspective About Inclusive Education in the Pacific. In Working with Families for Inclusive Education: Navigating Identity, Opportunity and Belonging; Scorgie, K., Sobsey, D., Eds.; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2017; pp. 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Magnússon, G.; Göransson, K.; Lindqvist, G. Contextualizing inclusive education in educational policy: The case of Sweden. Nord. J. Stud. Educ. Policy 2019, 5, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Cho, M.-H. Parents’ Use of Mobile Documentation in a Reggio Emilia-Inspired School. Early Child. Educ. J. 2019, 47, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, M.; Engelbrecht, P.; Nel, N.; Tlale, D. South African teachers’ views of collaboration within an inclusive education system. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2014, 18, 903–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).