Abstract

Background: Mixed-reality simulations (MRS) have been available for some time. However, teacher education programs in the United States are now introducing MRS as part of teacher training. Therefore, this study sought to determine teacher candidates’ perceptions of MRS and their possible benefits for education. Objectives: The purpose of this case study was to determine factors associated with a positive simulation experience, the simulation improvements or concerns, and what the teacher candidates learned from the live session. Methods: A qualitative methodological approach was employed. Feedback results were collected from 57 teacher candidates who participated in the MRS session, which were analyzed using an Excel document to identify the emergent themes. Results and Conclusions: The qualitative data revealed three themes: the real-life experiences were beneficial in acquiring pedagogical skills; the simulation was an effective training resource; and there was a need to improve the technology to ensure more realistic experiences. The simulation enables pre-service teachers to engage, think critically, and apply teaching skills with a small group of students. Conducting only one simulation was not enough to acquire knowledge on best teaching practices. Therefore, there is a need to implement additional MRS scenarios at the university level, so that teacher candidates can practice and feel confident teaching students in a safe environment.

1. Introduction

To acquire the pedagogical knowledge to teach in traditional face-to-face courses, teacher credential courses in the United States give teacher candidates classroom management and teaching skills using lectures, fieldwork, group activities, research papers, assignments, videos, discussion postings, and course textbooks. More recently, mixed-reality simulations (MRS), which are a combination of real and virtual environments that provide full, immersive teaching experiences, are being used as supplementary activities to further develop teaching skills.

This study gathered teacher candidates’ perceptions of MRS after they participated in a foundations course in September 2022.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 comprehensively reviews the use of MRS in teacher education programs, identifies its possible advantages for teacher education, and outlines the current study. Section 3 explains the study methods and instruments, Section 4 details and discusses the findings, Section 5 gives the limitations and suggests future research directions, Section 6 considers the implications of the findings, and Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Role of Mixed Reality Simulation in Teacher Education

As MRS is being included in many teacher education programs, there has been significant research into its efficacy and applicability [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Simulations re-create aspects of reality to gain new information, values, and cultural understanding or to develop a necessary skill for a profession [12]. Simulation-based training has also been a common tool in other professions; for example, simulations are used in the healthcare profession to acquire anatomical and surgical knowledge [13] and in other industries such as aviation to train pilots.

Simulations promote higher-order learning, critical thinking, and self-directed learning. As MRSs are ambiguous or open-ended, they encourage learners to contemplate the implications of the scenario, and, because they emulate real life, they can engage the interest of the students. MRS participants interact with a simulated environment that has real objects or individuals who engage with each other in real time [1]. In 2015, TLE TeachLivE, software designed for the educational development of pre-service teachers, began a working partnership with a company called Mursion [14]. Mursion has developed MRS for teacher candidate programs that allow them to interact with the Mursion-designed student avatars in classroom environments. The avatars respond to the teacher candidates’ questions and allow them to role-play student responses [15]. During the MRS, the teacher candidates can practice various teaching techniques, such as communication, making decisions in real time, managing student behavior, and testing different outcomes [16].

Additionally, MRS has served its purpose during the COVID-19 pandemic when many universities were suddenly disrupted from teaching face to face and had to quickly shift teaching styles to an online setting. The need to include MRS technology in various teacher education programs has enabled teacher candidates to learn, understand, and grow in the knowledge of classroom management and teaching during the pandemic. This type of practice-based technology program in teacher education requires scaffolded simulations whereby instructors decrease direct instruction as candidates become more competent in learning on their own with scaffolding tools such as MRS [17]. The use of MRS provides teacher candidates with necessary benefits in learning such as improved training transfer to real-world teaching scenarios [17].

2.2. Advantages of Mixed Reality Simulation

MRS can benefit teacher education programs by increasing the teacher candidates’ confidence and self-efficacy. In an MRS study on 13 pre-service teachers, 10 participants felt an improved level of confidence in their teaching in live classrooms and 9 felt more confident in handling difficult situations after receiving and dealing with unfavorable reactions from the avatar. Overall, the MRS helped prepare the pre-service teachers to handle challenging students in live classrooms [1].

Confidence levels have been found to increase in pre-service teachers who participate in MRS. For example, Piro and O’Callaghan [2] found that when pre-service teachers continued to interact with the MRS, they became more confident in speaking and utilizing the language needed for teaching. Ledger et al. [3] reported that pre-service teachers who had participated in MRS began to adopt questioning and direct instruction approaches in their teaching and concluded that their teaching confidence had increased because of the teaching strategies used during the MRS.

Another MRS advantage has been the pre-service teachers’ increased self-efficacy and their ability to achieve the desired student interest and learning results even for challenging and apathetic students [18]. A systematic study found that the MRS had increased the participants’ self-efficacy and understanding of how to teach. The pre-service teachers were also found to have developed an understanding of their professional teaching identities by dealing with the difficult behavioral management and lesson plan delivery situations in the MRS [11]. Peterson-Ahmad [4] also found that the self-efficacy in the teacher candidates increased with the rate of response opportunities they faced in the MRS, which led to a decrease in disruptive student behavior and an increase in on-task behavior. Gundel and Piro [5] also concluded that MRS could enhance self-efficacy through enactive learning and peer observation. The teacher candidates felt that they were able to assume the role of the teacher by problem solving and trying new teaching practices, and reported that watching their peers during the simulation helped strengthen their pedagogical skills. Generally, it has been found that when teacher candidates are given advanced opportunities to learn about teaching methodologies and practice different strategies and approaches, there is a greater chance that they will continue in the teaching profession [6].

Overall, the literature review revealed that MRS can successfully prepare teacher candidates to teach with confidence and self-efficacy and can equip and prepare them for real-life settings.

2.3. Mixed Reality Simulation Challenges

However, some challenges to using MRS have been found for beginning teacher candidates. The first challenge is for the teacher candidates to believe they are interacting with real students in a live classroom environment. Dieker et al. [7] noted that teacher candidates must suspend their disbelief during the simulations to enable the relevant learning to take place. In a case study conducted by Garland et al. [19], the few participants who had felt they were working with real students in a classroom were found to have enhanced their learning. However, suspension of disbelief has not always been successful. Dalinger et al. [1] found that two pre-service teachers involved in an MRS felt that the avatars looked ‘awkward’, ‘strange’, and ‘computer-generated’, and commented that ‘they look so fake’ and ‘robotic’ and that ‘it freaked me out’. In another mixed-methods design study, Hudson et al. [8] found that 11 out of 29 pre-service teachers felt that the MRS was unrealistic. Therefore, it can be difficult to convince teacher candidates that they are participating in an authentic environment, which can affect their teaching performances [1]. Participants may feel apprehensive and have difficulty connecting to the avatars as students. This limitation warrants further study and research, as this was also found in this study, with several teacher candidates saying that they were uncomfortable talking with the avatars. This is discussed in more detail in the findings section.

Another challenge during MRSs has been the presence of peers. Gordon et al.’s [11] systematic review found that teacher candidates had trouble learning from the experience when their peers were present, while the teacher candidates in Stavroulia et al.’s [9] study reported feeling stress, anxiety, confusion, embarrassment, and fear during the MRS, and Larson et al. [10] found that the teacher candidates experienced increased anxiety or nervousness because of a need to perform well in front of their peers. Larson et al. [10] concluded that teacher candidates needed more information about the avatars in advance and more frequent simulation practice to reduce their anxiety. Dalinger et al. [1] also found that some teacher candidates felt challenged, frightened, distracted, nervous, and hesitant when being watched by their peers during the MRS. As detailed in the Findings Section, this study also found that 29% of the teacher candidates (14 out of 49) felt that the technology needed to be more advanced so that the interactions between the avatars and teachers were more realistic.

MRS can cause teacher candidates to experience some level of discomfort [2]. Gordon et al. [11] reported that when teacher candidates observed their peers before engaging in the simulation, they felt better prepared about what to expect and how to interact during the simulation. Dalgarno et al. [20] reported that after watching their peers in the simulation, the teacher candidates became more conscious about how to interact and made them more willing to use direct instruction strategies, active learning, or questioning during the simulation [3].

Therefore, as previous studies have noted that teacher candidates can experience anxiety and self-consciousness when being watched by their peers during an MRS, further research on this aspect is necessary. One possible consideration could be to change the group setting MRS approach and another alternative could be to conduct the MRS with only the participant or co-participants present. What is evident from these previous studies is that the teacher candidates’ emotions need to be considered when using new technology. Therefore, teacher educator programs should ensure that new technologies such as MRS support a fruitful transition to the classroom [21] by fully preparing teacher candidates for the experience.

2.4. The Present Study

This case study was inspired by participating in a MRS at a conference hosted by the Branch Alliance for Educator Diversity or Branch Ed. The first author received funding from the Branch Alliance for Educator Diversity to participate in an MRS Summer Institute called Immerse, Imagine, Innovate: Teacher Educators Using MRS (MRS), in May 2022, which was held in Orlando, Florida. Around 20 university-level participants from the United States came to the three-day conference, at which they experienced elementary, secondary, and administrative avatar simulations.

At the end of the Summer Institute, the primary author was asked to develop a scenario for beginning teacher candidates enrolled in the foundation course at a private Christian university in Southern California. The first author designed a scenario called ‘What is in Your Heart’ for beginning teacher candidates to practice effective student communication.

Because few studies have been conducted on MRS and beginning teacher candidates, the first author sought to understand the perceptions of these beginning teacher candidates on the value of MRS in teacher training courses. Therefore, this study was conducted to determine the teacher candidates’ key takeaways, identify areas of improvement, and whether conducting teaching using avatars with learning differences assists in practicing and developing teaching practice knowledge.

3. Objectives

3.1. General Objectives

The overall aim of MRS in a teacher education program is to provide beginning teacher candidates with a learning tool that is designed to improve teaching skills. MRS is a technology that provides simulations of real-life situations where beginning teacher candidates can put their knowledge and teaching skills into current practice. Overall, the goal of MRS is to provide an immersive experience in which beginning teacher candidates can explore a virtual classroom environment that helps to educate participants.

3.2. Specific Objectives

There are several specific objectives of MRS. First, beginning teacher candidates will be able to interact with student avatars in a safe and controlled environment. Second, teacher candidates will be able to demonstrate the art of teaching by direct questioning, responding to avatars’ answers, and providing feedback. Third, teacher candidates will be able to identify the different behavioral characteristics of the five avatars and teach according to their differences. Fourth, teacher candidates will be able to demonstrate classroom management during the MRS scenario. Finally, teacher candidates who are not participating in MRS will be able to observe other teacher candidates and acquire new teaching strategies.

4. Methods

4.1. Procedures

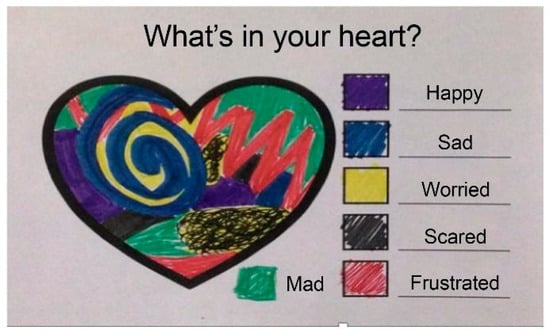

Before the simulation, the teacher candidates completed a ‘What is in Your Heart’ activity to understand the social–emotional learning (SEL) component of the foundation course (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

What’s In Your Heart?

In Figure 1, the colors denote the teacher candidates’ emotions. On the day of the simulation, all candidates were asked to bring their ‘What is in Your Heart’ activity to the simulation. First, the author gave a brief history of MRS, after which two teacher candidates took on roles as seventh-grade co-teachers and brought their completed ‘What is in Your Heart’ to the simulation, with the objective being to engage in an open discussion with the avatars about the ‘What is in Your Heart’ drawings.

The five avatars in the scenario had already learned about self-regulation, breathing techniques, and mindfulness from their co-teachers during Home Room and after lunch. The avatars were requested to independently complete the ‘What is in Your Heart’ activity after learning about SEL. The avatars, whose behaviors and responses were determined by a live actor or interactor, brought their activities and shared their emotions and colors with the co-teachers during the scenario. The live actor worked behind the scenes to view the teacher candidates as they participated in the simulation and responded as middle school students.

In Figure 2, the avatars were as follows: Savannah Boyd was an introvert who preferred working independently in a quiet setting; Dev Kapoor was an open-minded introvert who enjoyed bands and maths; Ava Russo was an extrovert, a rule follower and a quick thinker; Jasmine Walker was an introvert, loved science and history, and struggled with constructive criticism; and Ethan Mullen-Hardy had high energy, responded well to direct instructions, and was an adventurous learner. The avatar students’ biographical information was taken from the MRS Guidance Document provided by the Branch Alliance for Educator Diversity [22].

Figure 2.

Middle School Students as Avatars.

The MRS was set at a low-intensity level so that the avatars displayed few behavioral issues; that is, the avatars were generally compliant and responded to the teacher candidates with little to no pushback. A low-intensity level was seen to be more suited to the teacher candidates’ abilities as most had had little or no experience teaching students in a classroom. The MRS also had a medium-intensity level, which included non-compliance, talking out of turn, side talking, and potential power struggles [22], and a high-intensity level, which included frequent inappropriate behavior, such as cursing, power struggles, constant redirection, and constant disruptions [22].

Initially, the two teacher candidates took turns in front of a laptop computer connected to a projector head, which projected the simulation image onto a 90-inch display screen for all other participants to see. The teacher candidates were prompted to say ‘begin simulation’ before completing 10 min of co-teaching within the simulated classroom environment. As the teacher candidates did not have formal scripts, they began by introducing themselves, after which they moved to ask specific questions related to the ‘What is in Your Heart’ activity. The teacher candidates then discussed and interacted with the avatars in a fluid discussion by asking questions about the five avatar students’ feelings based on the color, sharing their perspectives, and probing for questions. At the end of the 10 min, the teacher candidates said ‘end simulation’, after which another two teacher candidates took their places in the MRS. The simulation was conducted for two days to enable all teacher candidates to participate.

4.2. Design and Participants

The purpose of this study was to explore the teacher candidates’ MRS experiences and perceptions of the simulated classroom and its applicability as a substitute for clinical and intern practices and teaching records.

This study sought to determine how the MRS experience could assist teacher candidates in communicating with diverse students and the benefits that could be gained from the experience. A qualitative research design was adopted. First, the teacher candidates’ comments and perceptions were collected, after which key themes were identified and analyzed.

Fifty-seven beginning teacher candidates were selected from one of the four September 2022 courses taught at a private Christian university. Approval was not needed for the study as ethical considerations had been considered beforehand. All selected teacher candidates were fully informed about the nature of the study and their participation was completely voluntary. No identifying information, such as names, ethnicity, gender, years of teaching, or ages was collected to ensure participant anonymity.

The participating teacher candidates were asked to complete three open-ended questions on a feedback form, all of which had been developed based on prior MRS research on education success and best practice factors. In Appendix A, the three questions on the feedback form were as follows:

- What were your positive experiences in the simulation?

- What concerns or recommendations do you have to improve the MRS?

- What did you learn from participating in this live session?

Before the study, these research questions had been compared to previous similar studies to ensure consistency and were deemed to be representative of what the study was trying to measure: the teacher candidates’ understanding and perceptions of MRS. This study was considered reliable as the results could be replicated under the same conditions.

All 57 participants were enrolled in the teacher education credentialing program, which is a private Christian undergraduate and graduate university located near Los Angeles in Southern California. The education faculty has teacher education programs designed for multiple subjects, single subjects, and education specialists. Most teacher candidates who enter the teaching credential program are pursuing a Master’s degree in education. Teacher candidates in the program are assigned to a regional center based on where they live, which allows them to take their teacher education courses either face to face or online.

The primary author co-taught a face-to-face foundation course to teacher candidates in September 2022 with a special education instructor. The 57 beginning teacher candidates, who were from one regional campus, planned to teach from kindergarten to 12th grade in public, private, or charter schools. Eleven or 19% of the teacher candidates were enrolled as education specialists to learn how to teach students with mild, moderate, or severe disabilities, 21 or 37% were pursuing multiple subject teaching credentials to teach at a TK–6th-grade level, and 25 or 44% were pursuing a single subject teaching credential to teach at 7th to 12th-grade levels. Eight or 14% were male and 49 or 86% were female. The age of the 57 teacher candidates ranged from 23 to 50 years. Teacher candidates in this study had experiences as substitute teachers, long-term substitute teachers, beginning intern teachers, or paraprofessionals. However, 28 or 50% of the teacher candidates had very little to no teaching experience. Twenty or 35% of teacher candidates had 1–3 years of teaching experience. Eight or 14% of teacher candidates had 3–5 teaching years of experience. Two or 0.03% of teacher candidates had 4–7 years of teaching experience. Funding was provided by the Branch Alliance for Educator Diversity to implement the Mursion MRS. There was no other stipend given to the participants or the co-teachers participating in this simulation research.

5. Data Collection and Analysis

5.1. Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis Process

This study employed a qualitative research approach to explore the perspectives and experiences of 57 beginning teacher candidates who attended a class embedded with MRS. The researchers asked them to answer three questions regarding their positive experiences with MRS, concerns about improving MRS, and their learning gains from using MRS. Data were collected through anonymous written feedback forms, allowing participants to express their views in an open-ended manner. The data analysis process followed a thematic analysis method, which is a widely used approach in qualitative research for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns or themes within data [23]. The written responses were first manually transcribed verbatim into a spreadsheet for data management purposes. The researchers then engaged in an iterative process of data familiarization, involving repeated readings of the entire dataset to immerse themselves in the depth and breadth of the content. During this phase, initial ideas and potential coding categories were noted. Next, the researchers systematically coded the data by assigning labels or codes to relevant segments of text that captured key concepts, phrases, or meanings [24]. This coding process was conducted inductively, allowing the codes to emerge from the data itself, rather than imposing predetermined categories. Codes were regularly compared and refined to ensure consistency and capture nuances within the data. The coded data were then collated into potential themes, which captured patterned meanings or experiences across the dataset [25]. Themes were reviewed and refined through an iterative process, ensuring they accurately represented the coded data and addressed the research questions. Finally, the researchers conducted a deeper analysis of the themes, exploring their relationships, interconnections, and potential hierarchies. Representative quotes and examples from the data were selected to illustrate and substantiate each theme.

5.2. Findings and Discussion

The findings were synthesized and presented in a narrative format, supported by data extracts and a quantitative summary of response frequencies or percentages where appropriate. The findings were summarized in a table, along with explanations, as presented in this paper. This integration of qualitative and quantitative elements provided a rich and nuanced understanding of the beginning teacher candidates’ experiences and perspectives. Throughout the analysis process, the researchers maintained a reflexive stance, acknowledging their positionality and potential biases, and employing strategies such as peer debriefing and member checking to enhance the trustworthiness and credibility of the findings.

The feedback from data analysis results for the first question are shown in Table 1. As can be seen, 29% (18 respondents) found that the MRS had provided a realistic teaching experience and 21% (13 respondents) stated that the MRS was an effective tool to practice student engagement and was useful in helping them stay on task. All 57 teacher candidates answered the first question; however, six candidates responded to two different themes, which is why the total in Table 1 is 63. The following comments were representative of each theme/category in Table 1:

Table 1.

Question #1: What were your positive experiences in the simulation?

- Theme 1: provided real experiences—‘The personalities were very realistic and similar to students I have previously encountered’.

- Theme 2: engaged positively with avatars—‘The engagement with students based on prompts that were specific seemed most successful’.

- Theme 3: avatars responded well—‘All students were able to give at least a simple answer and then a more complex answer with additional questions’.

- Theme 4: avatars represented diverse student characters—‘I felt that the students’ personalities and characteristics were pretty accurately portrayed’.

- Theme 5: good chance to practice questioning—‘The collaboration with specific students and the jumping of question to question’.

- Theme 6: comfortable for interaction—‘I feel more comfortable interacting with students now’.

Table 2 summarizes the areas to be improved based on Question 2. Eight candidates did not respond to Question 2. The reason why teacher candidates may not have answered the questions was that they wanted to avoid giving a direct response to the question, they might not have felt inclined to contribute a response, or too much effort is required of them to continue writing their thoughts. It was found that 13% of the teacher candidates wanted more students in the simulations and 10% wanted to see more students with different learning needs, such as English learners, at-promise, and/or gifted students.

Table 2.

Question #2: What concerns or recommendations do you have to improve the MRS?

Even though the teacher candidates thought there were some benefits to be gained from the simulation, they also identified some areas that needed improvements. The most critical area of improvement referred to the need for updated simulation technology (29%, 14 comments out of 49), as shown in the following responses.

‘Improve the graphics to make it clearer when a student is speaking’.

‘More physical abilities like giving a thumbs up or down to questions for quicker group reference abilities’.

‘I would like to see the mouths of the students for a more realistic feel’.

‘Giving students access to move. By allowing the boys to sit together would be more comfortable’.

‘The voices sounded a little off. They sounded too old for the students’.

The main area to be improved was to have more authentic interactions with the avatars (16% or 8 comments), as expressed in the following comments.

‘More direct interruptions from students would be a more real-life situation’.

‘Keep switching up the personalities of the students so they feel more realistic’.

‘Have a different response for students who don’t want to interact’.

Table 3 shows the responses to Question 3. While 16 teacher candidates did not respond to Question 3, 27% (11 candidates out of 41) felt it was effective for teacher education preparation training, 27% felt it was a fun, enjoyable activity, 26% (12 candidates) felt that the MRS was a powerful learning experience, 26% (12 candidates) felt it was a fun learning experience, 22% (9 candidates) thought the MRS was a great learning tool, 14% (6 candidates) agreed the MRS was effective in providing opportunities to engage with diverse students or avatars, and 6% (3 candidates) commented that they needed more training to interact with the avatars before they could engage in the simulation.

Table 3.

Question #3: What did you learn from participating in this live session?

The following comments were representative of each theme/category in Table 3:

- Theme 1: MRS provided an effective training opportunity—‘I would love to have this more throughout my journey’.

- Theme 2: enjoyed interacting with avatars—‘I enjoyed! I would definitely practice on my own with this simulation to create lesson plans’.

- Theme 3: MRS is an effective tool—‘I think this is an amazing tool that every teacher candidate should experience’.

- Theme 4: effective opportunity to engage with diverse students—‘Quite accurate personalities and responses from students based on my experience’.

- Theme 5: need more training—‘I liked the way we get to practice being a teacher before becoming a teacher’.

This study sought to explore the beginning teacher candidates’ perceptions of MRS to determine the successful elements, the areas that needed improvements, and their overall impressions of the experience.

Three main themes emerged from the analysis of the student responses: real-time teaching practice, positive teaching experiences, and recommendations for improvements, each of which is discussed in more detail in the following subsections.

5.3. Real-Time Teaching Practice

Following the MRS scenarios, whole group discussions were conducted at each regional center regarding the survey that was completed by teacher candidates. As a group, co-instructors reviewed the survey to discuss emergent themes. The first theme that emerged was real-time teaching practice. Eighteen participants out of 63 responses, or 28.6%, felt that the MRS provided real-life experiences that could benefit them as teachers, as evidenced by the following comments: ‘having a diverse group of students that are very realistic to what we might come across, in terms of personality’; ‘the teacher-student interactions and the students listening when talking had a real-life feel’; and ‘the experiences were genuine and felt like the real thing’.

The opportunity to practice their teaching skills, such as communicating, asking direct questions, and managing a small group of students, was found to be realistic by many of the participants. Comments included the following: ‘the things that went well were the questions that were asked and how engaged students were’; ‘the engagement with students based on the prompt that was specific seemed most successful’; ‘the simulation was cool and the interactions with the students and their comments were eye-opening. I have never seen anything like this before’; ‘all students were able to give at least a simple answer, and then a more complex answer with additional questioning’; and ‘teacher candidates were able to fail and learn from their mistakes’. The findings supported Donnelly et al. [26], which concluded that professional knowledge, confidence, and teaching skills could be gained from simulations.

The candidates felt that the guidance and suggestions they received from their course instructors to improve their teaching skills helped them better process their experiences, as evidenced by the following comments: ‘feedback between the co-teachers and students during the simulation [was helpful]’; and the ‘live feedback on classroom management was given to help me understand about teaching’. This finding was similar to the findings of Walters et al. [27], who reported that positive and corrective feedback on teaching skills allowed the teacher candidates to learn and improve as teacher candidates and also corresponded with the results from Gundel and Piro [5], who reported that social encouragement from the professor and peers ‘was important, huge and very helpful’.

Many teacher candidates felt that the simulation provided them with the opportunity to interact with the avatars in a realistic environment, as evidenced by the following comments: ‘the personalities were very realistic and similar to students I have previously encountered’; and ‘I felt that the students’ personalities and characteristics were pretty accurately portrayed’. These comments were similar to the findings of Huang et al. [28], who found that virtual reality simulations provided a first-hand experience that triggered student interest in acquiring and practicing classroom management skills.

5.4. Positive Teaching Experiences

During the whole group discussion, another emergent theme was discussed and that was how MRS was a positive teaching experience for teacher candidates. The participants’ comments on their MRS experiences indicated that they felt this was an effective training opportunity, as evidenced by the following comments: ‘the simulation is powerful and interesting’; ‘I enjoyed this experience because I felt like I learned how to actually teach. I have no experience in teaching, so this definitely gave me the confidence on how to practice for my career’; ‘[MRS] is a cool program that helps prepare you for the classroom experience. I am happy with it and want more simulations’; ‘candidates were able to have a chance to get the feel of the classroom before they experience student teaching’; ‘I think it’s a very good practice tool for first-time teachers’; and ‘this was a unique experience that helped ease into being in a classroom’.

In sum, the MRS allowed the teacher candidates to learn new skills, such as handling students, classroom management, and direct questioning, which was in line with Larson et al. [10], who found that after practicing with simulations, there was an increase in the understanding of behavioral management techniques and competence in handling students in the classroom.

Many participants agreed that the interactions with the avatar in the simulation were a fun experience that assisted them in learning emotionally, as evidenced by the following comments: ‘super awesome technology and very useful in preparing for any type of situation or response’; ‘if you have never been in the classroom, this is a great response to the different personalities in the classroom. A little creepy, but fun!’; ‘insightful and fun’; and ‘I absolutely enjoyed the simulation activity’. These comments were also reflected in the findings of Larson et al. [10], who found that the pre-service teachers appreciated participating in the simulations, felt engaged, and relished the experience, as well as the findings of Gundel and Piro [5], who found that the teacher candidates had felt engaged, had developed emotional growth, and had an increased level of comfort during the simulation. Therefore, these results indicated that the MRS was an effective tool for teacher candidates to gain new insights into classroom teaching skills.

5.5. Technological Challenges

Another emergent theme that was discussed during whole group discussion time following the MRS scenario was technological challenges. Fourteen out of forty teacher candidates, or 28.6%, indicated that the MRS technology needed to be upgraded to provide more realistic classroom experiences, as evidenced in the following comments: ‘improve on graphics to make it clearer when a student is speaking. The mouth movement was not in sync when the avatar was speaking at times’; ‘[I] would like to see the mouth for the students or a more realistic feel’; and ‘[the] avatars could be more realistic and could use different words more’. Lew et al. [29] also commented on the limitations of MRS technology, such as the avatar’s inability to speak at the same time and express emotions.

A few participants commented that the avatar movement was restricted, with some making the following suggestions: ‘having the simulations (students) give a thumbs up or so that new candidates can use that strategy during the simulation’; ‘more physical abilities like, give a thumbs up or down to questions for more group quick reference abilities’; and ‘give [the] students access to move. Allow the boys to sit together so they would be more comfortable speaking’. Larson et al. [10] also found that the avatars were unable to physically move out of their chairs and were ‘clunky’.

One participant felt that more students than five were needed in the MRS, another said that a wider range of students would be better, and several participants wanted a wider representation of students with diverse learning differences instead of using only extroverts or introverts, such as English language learners, students with disabilities, students on 504 plans or individualized education plans, foster students and gifted, homeless, low socio-economic or at-promise students.

6. Limitations and Future Research

While the results of this study confirmed findings in previous research, there were several limitations. First, as only one out of four teacher education program foundation classes participated, the results cannot be generalized; therefore, future MRS research should include an in-depth data analysis from all four foundation classes to provide more comprehensive findings. Second, as this was the first MRS to be implemented in the teaching credential course, implementing it in other teacher education program foundation courses could provide more detailed results. Further, only one MRS session was conducted; however, if two sessions were conducted, the first and second session perceptions could be compared. Third, only the low-intensity MRS was implemented; therefore, future research could assess and compare the teacher candidate perceptions of the medium and high-intensity levels. Finally, the technology limitation concerns of the teacher candidates are going to be shared with the Mursion developers to assist them in improving and upgrading the MRS technology.

7. Implications

The results from the case study suggest that more research is needed on MRS and its impact on teacher candidates in teacher credential programs. This includes and is not limited to finding out how teacher candidates have achieved or demonstrated a level of proficiency in establishing classroom management, implementing teaching strategies, and increasing teaching pedagogical skills. These results should be considered when looking at the efficacy of MRS in teacher credentialing programs. Faculty, chairs, and deans at the university level can determine the level of frequency and duration of MRS for teacher candidates to experience based on existing data or survey results. While previous research has focused on MRS in teacher education programs, these results show that teacher candidates highly benefited from technology, which enabled them to craft their teaching skills when implemented in a comfortable setting with the presence of their cohorts.

8. Conclusions

MRS is a cutting-edge technology that is shaping the future of teacher credential programs across the United States [1,11,19]. As evidenced in this study, MRS has the potential to assist teacher candidates in gaining classroom management skills, teaching strategies, and questioning techniques before entering a real classroom [2,15]. Based on beginning teacher candidates’ MRS experiences, the hope is to prepare the next generation of teacher candidates to make positive and meaningful impacts on their students. Overall, the MRS experience was found to be a positive and empowering experience that helped shape the teacher candidates’ pedagogical skills; however, there are still a few technological limitations.

9. Ethical Considerations

In this case study, no approval was needed for the study as ethical considerations were considered beforehand. All participants were fully informed about the nature of the study and their participation was completely voluntary. Consent was obtained from the participants verbally before the simulation began. Further, no identifying information such as names, ethnicity, gender, years of teaching, or age was collected or published, ensuring the anonymity of the participants. The authors took care to ethically conduct this study. Generally, class activities that involve standard educational practices such as surveys do not pose any risk to participants and are exempted from formal ethical review. Additionally, this research was a non-interventional study that involved surveys and ethical approval was not required because of national laws [30].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M.F. and H.L.; methodology, H.L.; software, H.L.; validation, I.M.F. and H.L.; formal analysis, H.L.; investigation, I.M.F.; resources, H.L.; data curation, H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, I.M.F.; writing—review and editing, I.M.F.; visualization, I.M.F.; supervision, I.M.F.; project administration, I.M.F.; funding acquisition, I.M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to ethical considerations were considered beforehand. All participants were fully informed about the nature of the study and their participation was completely voluntary.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The following three questions were asked following the MRS practice:

1. What is your positive experience with simulation?

2. What is your concern or recommendation to improve MRS?

3. What did you learn from participating in this live session?

References

- Dalinger, T.; Thomas, K.B.; Stansberry, S.; Xiu, Y. A mixed reality simulation offers strategic practice for pre-service teachers. Comput. Educ. 2020, 144, 103696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piro, J.S.; O’callaghan, C. Journeying towards the profession: Exploring liminal learning within mixed reality simulations. Action Teach. Educ. 2019, 41, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersozlu, Z.; Ledger, S.; Fischetti, J. Preservice teachers’ confidence and preferred teaching strategies using TeachLivE ™ virtual learning environment: A two-step cluster analysis. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2019, 15, em1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson-Ahmad, M. Enhancing pre-service special educator preparation through combined use of virtual simulation and instructional coaching. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundel, E.; Piro, J.S. Perceptions of self-efficacy in mixed reality simulations. Action Teach. Educ. 2021, 43, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, R.; Merrill, L.; May, H. Retaining teachers: How preparation matters. Educ. Leadersh. 2012, 69, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Dieker, L.A.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Lignugaris/Kraft, B.; Hynes, M.C.; Hughes, C.E. The potential of simulated environments in teacher education: Current and future possibilities. Teach. Educ. Spéc. Educ. J. Teach. Educ. Div. Counc. Except. Child. 2013, 37, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, M.E.; Voytecki, K.S.; Owens, T.L.; Zhang, G. Preservice teacher experiences implementing classroom management practices through mixed-reality simulations. Rural. Spéc. Educ. Q. 2019, 38, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavroulia, K.E.; Makri-Botsari, E.; Psycharis, S.; Kekkeris, G. Emotional experiences in simulated classroom training environments. Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 2016, 33, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, K.E.; Hirsch, S.E.; McGraw, J.P.; Bradshaw, C.P. Preparing preservice teachers to manage behavior problems in the classroom: The feasibility and acceptability of using a mixed-reality simulator. J. Spéc. Educ. Technol. 2020, 35, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ade-Ojo, G.O.; Markowski, M.; Essex, R.; Stiell, M.; Jameson, J. A systematic scoping review and textual narrative synthesis of physical and mixed-reality simulation in pre-service teacher training. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2022, 38, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, B.C.; Patterson, J. Cross-cultural simulations in teacher education: Developing empathy and understanding. Multicult. Perspect. 2005, 7, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, C.A.; Li, E.H.; Jimenez, D.E.; Milanaik, R.L. Augmented reality in medical education and training: From physicians to patients. In Augmented Reality in Education; Geroimenko, V., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2020; pp. 111–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, D.; Kick in’ It New School. A Cutting-Edge Classroom Simulator at UCF Is Helping Educators Become Better Teachers. Pegasus: The Magazine of the University of Central Florida. 2017. Available online: https://www.ucf.edu/pegasus/kickin-new-school/ (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Bradley, E.G.; Kendall, B. A review of computer simulations in teacher education. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2014, 43, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, D.; Ireland, A. Enhancing teacher education with simulations. TechTrends 2016, 60, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarles, J.; Lampotang, S.; Fischler, I.; Fishwick, P.; Lok, B. Scaffolded learning with mixed reality. Int. J. Syst. Appl. Comput. Graph. 2009, 33, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M.; Hoy, A.W. The differential antecedents of self-efficacy beliefs of novice and experienced teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2007, 23, 944–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, K.M.V.; Holden, K.; Garland, D.P. Individualized Clinical Coaching in the TLA TeachLivE Lab: Enhancing Fidelity of Implementation of System of Least Prompts Among Novice Teachers of Students With Autism. Teach. Educ. Spéc. Educ. J. Teach. Educ. Div. Counc. Except. Child. 2015, 39, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalgarno, B.; Charles Sturt University; Gregory, S.; Knox, V.; Reiners, T. Practising teaching using virtual classroom role plays. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2016, 41, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podolsky, A.; Kini, T.; Bishop, J.; Darling-Hammond, L. Solving the Teacher Shortage: How to Attract and Retain Excellent Educators; Learning Policy Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branch Alliance for Educator Diversity. MRS External Partners 2022: MRS Guidance Document. 2022. Available online: https://www.educatordiversity.org/ (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, D.; Fischetti, J.; Ledger, S.; Boadu, G. Using a mixed-reality microteaching program to support ‘at risk’ preservice teachers. In Work-Integrated Learning Case Studies in Teacher Education: Epistemic Reflexivity; Winslade, M., Loughland, T., Eady, M.J., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, S.M.; Hirsch, S.E.; McKown, G.; Carlson, A.; Allen, A.A. mixed-reality simulation with preservice teacher candidates: A conceptual replication. Teach. Educ. Spéc. Educ. J. Teach. Educ. Div. Counc. Except. Child. 2021, 44, 340–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Richter, E.; Kleickmann, T.; Richter, D. Comparing video and virtual reality as tools for fostering interest and self-efficacy in classroom management: Results of a pre-registered experiment. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2023, 54, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, S.; Gul, T.; Pecore, J.L. ESOL pre-service teachers’ culturally and linguistically responsive teaching in mixed-reality simulations. Inf. Learn. Sci. 2021, 122, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dove Press Limited. Research Ethics and Consent. 2024. Available online: https://www.dovepress.com/editorial-policies/research-ethics (accessed on 9 February 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).