Using Technology-Supported Approaches for the Development of Technical Skills Outside of the Classroom

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Simulation Design

2.2. Learning Environment

2.3. Acceptability and Feasibility

3. Results

3.1. Conceptual Framework for the Design and Integration of a Take-Home Simulation

3.2. Using the Framework to Prototype a Take-Home Suturing Simulation

3.2.1. Simulation Design

- Clinical domain: appropriate and safe administration of the local anaesthetic; safe and appropriate use of suturing instruments; appropriate tissue handling, suture placement to relocate tissues and promote healing; suture handling and knot tying; and appropriate levels of infection control and sharps protection.

- Knowledge domain: understanding of the local anaesthetic agents, along with its indications and contraindications; understanding of the local anatomy; a critical understanding of the aims of the suturing technique and how adapt it to the current circumstances; and an understanding of the suture material and its selection.

- Communication domain: ability to effectively communicate with a dental nurse and the patient to ensure effective procedure delivery as well as manage any anxiety; confirm consent; and write up the case notes.

- Management and Leadership: ability to work effectively and lead the team and mitigate for human factors.

- Professionalism: ability to take responsibility for the procedure and its outcome; identify any on-going personal developmental needs.

- Clinical domain: the mechanics of tying a knot and moving the hands—demonstrating the safe and appropriate use of suturing instruments; appropriate tissue handling and suture placement to relocate tissues and promote healing; suture handling and knot tying; and appropriate levels of infection control and sharps protection [63].

- Knowledge domain: a critical understanding of the aims of the suturing technique and some insight into the ability to adapt it to the current circumstances; and an understanding of the suture material and its selection.

- Professionalism: ability to identify any on-going developmental needs and address them through deliberate practice.

- Simulation 1—Provide learning support over key knowledge aspects, highlighting to learners the links to the real-world task, e.g., relationships between suture handling, knot tying, and placement, as well as tissue blood supply and healing. The simulation was carefully designed to require a focus on the identified threshold skills and minimise the cognitive load by requiring learners to practice the simplest form of suturing. The interpretation use argument [40] indicated that the scoring approach (see later) would be appropriate to demonstrate the areas identified in the clinical, knowledge, and professional domains, meaning that at the point of demonstrating performance consistency, learners would show evidence of having gained the required skills and being ready to move to the next simulation.

- Simulation 2—Increase the difficulty of the suture placement by limiting access to the suture site using a simple physical barrier (a plastic cup with the bottom cut off), focusing again on the identified threshold skills. The interpretation use argument [40] indicated that this limited level of generalisability, combined with the scoring approach and growing longitudinal data, would show evidence of having gained the required skills and being ready to move to the next simulation.

- Simulation 3—Introduce new suturing techniques that again increase the stretch in the identified threshold skills. The interpretation use argument [40] indicated that this increased level of generalisability, combined with the scoring approach and growing longitudinal data, would show evidence of having gained the required skills and being ready to move to the next simulation.

- Simulation 4—In a simulation suite, move to placing sutures in a phantom head that limits access and has more realistic soft tissues; increase stretch through altering suture location and type. The interpretation use argument [40] indicated that this increased level of generalisability, combined with more sophisticated evidence of extrapolation, the scoring approach, and growing longitudinal data, would show evidence of having gained the required skills and being ready to move to the next simulation.

- Simulation 5—Introduce suture placement on a real patient, commencing with simple and moving to more complex.

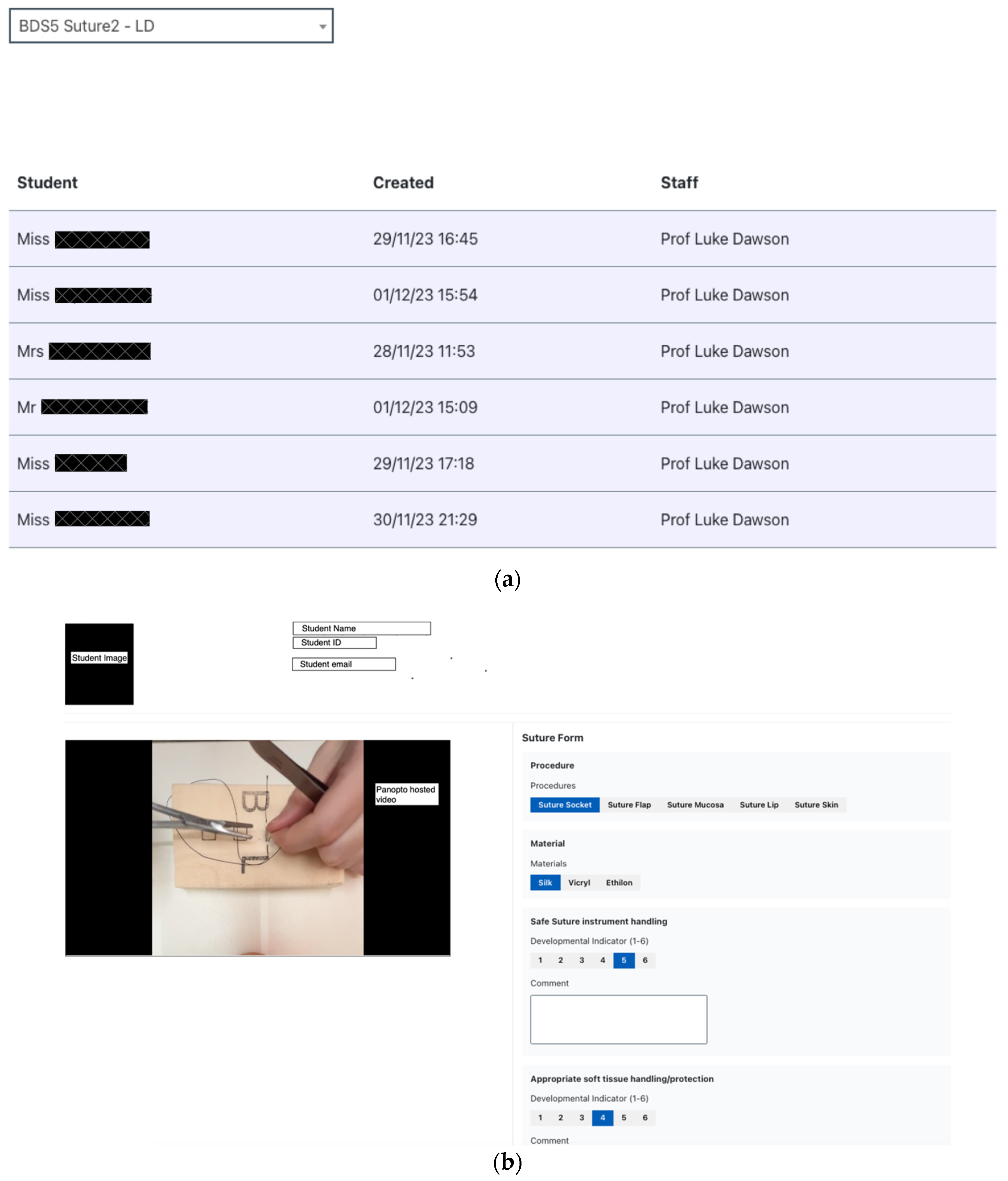

3.2.2. Learning Environment

3.2.3. Acceptability and Feasibility

- Learner engagement was, and continues to be, very high.

- The approach has significantly increased the deliberate practice/feedback opportunities compared to the existing pre-COVID-19 system.

- The approach has significantly increased the complexity of opportunities compared to the existing pre-COVID-19 system.

- Learner feedback has been highly supportive, and anecdotal feedback indicated that a significant number believed their confidence with respect to suturing had increased; further detailed work is needed.

- Staff compliance was universally high, and there we no issues with providing feedback, which only took a few minutes per student due to the integrated design of the web portal. This included watching the uploaded video that was normally 1–2 min long.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mason, W.T.M.; Strike, P.W. Short Communication See One, Do One, Teach One‚ Alas This Still How It Works? A Comparison of the Medical and Nursing Professions in the Teaching of Practical Procedures. Med. Teach. 2003, 25, 664–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, M.; Irby, D.M.; Reznick, R.K.; MacRae, H. Teaching Surgical Skills—Changes in the Wind. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 2664–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaghie, W.C.; Issenberg, S.B.; Cohen, E.R.; Barsuk, J.H.; Wayne, D.B. Does Simulation-Based Medical Education With Deliberate Practice Yield Better Results Than Traditional Clinical Education? A Meta-Analytic Comparative Review of the Evidence. Acad. Med. 2011, 86, 706–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, D.A.; Hamstra, S.J.; Brydges, R.; Zendejas, B.; Szostek, J.H.; Wang, A.T.; Erwin, P.J.; Hatala, R. Comparative Effectiveness of Instructional Design Features in Simulation-Based Education: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med. Teach. 2013, 35, e867–e898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, E.; Janssens, S.; McLindon, L.A.; Hewett, D.G.; Jolly, B.; Beckmann, M. Improved Laparoscopic Skills in Gynaecology Trainees Following a Simulation-training Program Using Take-home Box Trainers. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 59, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motola, I.; Devine, L.A.; Chung, H.S.; Sullivan, J.E.; Issenberg, S.B. Simulation in Healthcare Education: A Best Evidence Practical Guide. AMEE Guide No. 82. Med. Teach. 2013, 35, e1511–e1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, J.L.; Østergaard, D.; LeBlanc, V.; Ottesen, B.; Konge, L.; Dieckmann, P.; Vleuten, C.V. der Design of Simulation-Based Medical Education and Advantages and Disadvantages of in Situ Simulation versus off-Site Simulation. BMC Med. Educ. 2017, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GDC General Dental Council. Preparing for Practice; GDC: London, UK, 2015.

- GDC General Dental Council. Standards for Education; GDC: London, UK, 2015.

- Issenberg, S.B.; Mcgaghie, W.C.; Petrusa, E.R.; Gordon, D.L.; Scalese, R.J. Features and Uses of High-Fidelity Medical Simulations That Lead to Effective Learning: A BEME Systematic Review. Med. Teach. 2005, 27, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todsen, T.; Henriksen, M.V.; Kromann, C.B.; Konge, L.; Eldrup, J.; Ringsted, C. Short- and Long-Term Transfer of Urethral Catheterization Skills from Simulation Training to Performance on Patients. BMC Med. Educ. 2013, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, S.; Bridges, S.M.; Burrow, M.F. A Review of the Use of Simulation in Dental Education. Simul. Healthc. J. Soc. Simul. Healthc. 2015, 10, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willaert, W.I.M.; Aggarwal, R.; Herzeele, I.V.; Cheshire, N.J.; Vermassen, F.E. Recent Advancements in Medical Simulation: Patient-Specific Virtual Reality Simulation. World J. Surg. 2012, 36, 1703–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler-Schwartz, A.; Bissonnette, V.; Mirchi, N.; Ponnudurai, N.; Yilmaz, R.; Ledwos, N.; Siyar, S.; Azarnoush, H.; Karlik, B.; Maestro, R.F.D. Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education: Best Practices Using Machine Learning to Assess Surgical Expertise in Virtual Reality Simulation. J. Surg. Educ. 2019, 76, 1681–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saud, L.M. The Utility of Haptic Simulation in Early Restorative Dental Training: A Scoping Review. J. Dent. Educ. 2021, 85, 704–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Lucock, M. The Mental Health of University Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Online Survey in the UK. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adedoyin, O.B.; Soykan, E. Covid-19 Pandemic and Online Learning: The Challenges and Opportunities. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 31, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlburg, D.A. COVID-19 and UK Universities. Political Q. 2020, 91, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ironsi, C.S. Navigating Learners towards Technology-Enhanced Learning during Post COVID-19 Semesters. Trends Neurosci. Educ. 2022, 29, 100189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, D. A Six-Step Approach to Curriculum Development. In Curriculum Development for Medical Education a Six-Step Approach; Thomas, P., Kern, D., Hughes, M., Chen, B., Eds.; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2009; pp. 5–9. ISBN 9780801893667. [Google Scholar]

- Khamis, N.N.; Satava, R.M.; Alnassar, S.A.; Kern, D.E. A Stepwise Model for Simulation-Based Curriculum Development for Clinical Skills, a Modification of the Six-Step Approach. Surg. Endosc. 2016, 30, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weick, K.E. Theory Construction as Disciplined Imagination. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 516–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, E. Designing Conceptual Articles: Four Approaches. AMS Rev. 2020, 10, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macluskey, M.; Hanson, C. The Retention of Suturing Skills in Dental Undergraduates: Retention of Suturing Skills. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2011, 15, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macluskey, M.; Durham, J.; Balmer, C.; Bell, A.; Cowpe, J.; Dawson, L.; Freeman, C.; Hanson, C.; McDonagh, A.; Jones, J.; et al. Dental Student Suturing Skills: A Multicentre Trial of a Checklist-Based Assessment: Dental Student Suturing Skills. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2011, 15, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safir, O.; Williams, C.K.; Dubrowski, A.; Backstein, D.; Carnahan, H. Self-Directed Practice Schedule Enhances Learning of Suturing Skills. Can. J. Surg. 2013, 56, E142–E147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Fugill, M. Defining the Purpose of Phantom Head. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2013, 17, e1–e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellaway, R.H.; Kneebone, R.; Lachapelle, K.; Topps, D. Practica Continua: Connecting and Combining Simulation Modalities for Integrated Teaching, Learning and Assessment. Med. Teach. 2009, 31, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978; ISBN 0674576292. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, D.; Bruner, J.S.; Ross, G. The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1976, 17, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, K.A. An Expert-Performance Perspective of Research on Medical Expertise: The Study of Clinical Performance. Med. Educ. 2007, 41, 1124–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, K.A. Deliberate Practice and the Acquisition and Maintenance of Expert Performance in Medicine and Related Domains. Acad. Med. 2004, 79, S70–S81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrowski, A.; Park, J.; Moulton, C.; Larmer, J.; MacRae, H. A Comparison of Single- and Multiple-Stage Approaches to Teaching Laparoscopic Suturing. Am. J. Surg. 2007, 193, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brydges, R.; Carnahan, H.; Rose, D.; Rose, L.; Dubrowski, A. Coordinating Progressive Levels of Simulation Fidelity to Maximize Educational Benefit. Acad. Med. 2010, 85, 806–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aul, K.; Ferguson, L.; Bagnall, L. Students’ Perceptions of Intentional Multi-Station Simulation-Based Experiences. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2021, 16, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paas, F.; Renkl, A.; Sweller, J. Cognitive Load Theory and Instructional Design: Recent Developments. Educ Psychol 2003, 38, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.H.F.; Land, R. Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knoweldge: Linkages to Ways of Thinking and Practising within the Disciplines. In Improving Student Learning—Ten Years On; Rust, C., Ed.; Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Massoth, C.; Röder, H.; Ohlenburg, H.; Hessler, M.; Zarbock, A.; Pöpping, D.M.; Wenk, M. High-Fidelity Is Not Superior to Low-Fidelity Simulation but Leads to Overconfidence in Medical Students. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva, K.W.; Bordage, G.; Campbell, C.; Galbraith, R.; Ginsburg, S.; Holmboe, E.; Regehr, G. Towards a Program of Assessment for Health Professionals: From Training into Practice. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2015, 21, 897–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M.T. Validating the Interpretations and Uses of Test Scores: Validating the Interpretations and Uses of Test Scores. J. Educ. Meas. 2013, 50, 1–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.A.; Brydges, R.; Ginsburg, S.; Hatala, R. A Contemporary Approach to Validity Arguments: A Practical Guide to Kane’s Framework. Med. Educ. 2015, 49, 560–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, L.J.; Fox, K.; Jellicoe, M.; Adderton, E.; Bissell, V.; Youngson, C.C. Is the Number of Procedures Completed a Valid Indicator of Final Year Student Competency in Operative Dentistry? Brit. Dent. J. 2021, 230, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, D.A.; Artino, A.R. Motivation to Learn: An Overview of Contemporary Theories. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Perceived Self-Efficacy in Cognitive Development and Functioning. Educ. Psychol. 1993, 28, 117–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Exercise of Personal and Collective Efficacy in Changing Societies. In Self-Efficacy in Changing Societies; Cambridge University: New York, NY, USA, 1995; p. 3. ISBN 0521474671. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, P.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Parker, P.; Kingsford-Smith, A.; Zhou, S. Cognitive Load Theory and Its Relationships with Motivation: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 36, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Attaining Self-Regulation: A Social Cognitive Perspective. In Handbook of Self-Regulation; Boekaerts, M., Zeidner, M., Pintrich, P.R., Eds.; Part I: General Theories and Models of Self-Regulation; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 13–39. ISBN 978-0-12-109890-2. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C.S. The Development of Ability Conceptions. In Development of Achievement Motivation; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 57–88. ISBN 9780127500539. [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe, A.; Johnson, S. Thanks, but No-Thanks for the Feedback. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2016, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, L.; Fox, K. Can Assessment Be a Barrier to Successful Professional Development? Phys. Ther. Rev. 2017, 21, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, K. “Climate of Fear” in New Graduates: The Perfect Storm? Br. Dent. J. 2019, 227, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, D.J.; Dick, D.M. Formative Assessment and Self-regulated Learning: A Model and Seven Principles of Good Feedback Practice. Stud. High. Educ. 2006, 31, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, B.; Arutiunian, A.; Micallef, J.; Sivanathan, M.; Wang, Z.; Chorney, D.; Salmers, E.; McCabe, J.; Dubrowski, A. From Centralized to Decentralized Model of Simulation-Based Education: Curricular Integration of Take-Home Simulators in Nursing Education. Cureus 2022, 14, e26373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vleuten, C. The Assessment of Professional Competence: Developments, Research and Practical Implications. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 1996, 1, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vleuten, C.; Schuwirth, L. Assessing Professional Competence: From Methods to Programmes. Med. Educ. 2005, 39, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Vleuten, C.P.; Schuwirth, L.W.; Driessen, E.W.; Dijkstra, J.; Tigelaar, D.; Baartman, L.K.; van Tartwijk, J. A Model for Programmatic Assessment Fit for Purpose. Med. Teach. 2012, 34, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heeneman, S.; de Jong, L.H.; Dawson, L.J.; Wilkinson, T.J.; Ryan, A.; Tait, G.R.; Rice, N.; Torre, D.; Freeman, A.; Vleuten, C.P.M. van der Ottawa 2020 Consensus Statement for Programmatic Assessment-1. Agreement on the Principles. Med. Teach. 2021, 43, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torre, D.; Rice, N.E.; Ryan, A.; Bok, H.; Dawson, L.J.; Bierer, B.; Wilkinson, T.J.; Tait, G.R.; Laughlin, T.; Veerapen, K.; et al. Ottawa 2020 Consensus Statements for Programmatic Assessment-2. Implementation and Practice. Med. Teach. 2021, 43, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, L.; Mason, B.; Bissell, V.; Youngson, C. Calling for a Re-Evaluation of the Data Required to Credibly Demonstrate a Dental Student Is Safe and Ready to Practice. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2016, 21, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Darzi, A.; Bann, S.D.; Butler, P.E. Suturing: A Lost Art. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2002, 84, 278–279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Govaerts, M.; Vleuten, C.P. Validity in Work-based Assessment: Expanding Our Horizons. Med. Educ. 2013, 47, 1164–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, S.C.; Scaffidi, M.A.; Khan, R.; Garg, A.; Al-Mazroui, A.; Alomani, T.; Yu, J.J.; Plener, I.S.; Al-Awamy, M.; Yong, E.L.; et al. Progressive Learning in Endoscopy Simulation Training Improves Clinical Performance: A Blinded Randomized Trial. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2017, 86, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, X. Stories as Case Knowledge: Case Knowledge as Stories. Med. Educ. 2001, 35, 862–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biggs, J. Enhancing Teaching through Constructive Alignment. High Educ. 1996, 32, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, L.; Mason, B.; Balmer, C.; Jimmieson, P. Developing Professional Competence Using Integrated Technology-Supported Approaches: A Case Study in Dentistry; Fry, H., Ketteridge, S., Marshall, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, L.; Mason, B. Developing and Assessing Professional Competence: Using Technology in Learning Design. In For the Love of Learning: Innovations from Outstanding University Teachers; Bilham, T., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; p. 135. [Google Scholar]

- Mushtaq, F.; Williams, M.; Ahmed, B. Simulation-Based Dental Education: An International Consensus Report. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Question | Description |

|---|---|

| Safe suture instrument handling | The ability to use of all instruments, including suture needles, safely |

| Appropriate soft tissue handling/protection | The ability to protect the soft tissues from harm and handle them with reference to the blood supply to facilitate healing |

| Appropriate bites of tissue | The ability to take equal and perpendicular bites of tissue to help ensure equal tension across the wound |

| Appropriate knot tension | The ability to tighten the knot to the appropriate level to ensure effective healing or haemorrhage control |

| Appropriate knot position | The ability to place the knot buccally |

| Appropriate wound edge apposition | The ability to ensure adequate wound edge apposition |

| Ability to remove a suture | The ability to remove a suture, ensuring that no residual is left in the wound and the wound is not infected by the unnecessary transit of suture through the wound that has been exposed to the oral environment |

| Management of suture complication | The ability to demonstrate a systematic understanding of the risks and complications of the procedure, with recognition |

| Procedural knowledge | The ability to demonstrate, through action, that they possess the appropriate knowledge of the steps required to safely undertake the procedure in question |

| DI | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | UNABLE to do this. Has caused harm or does not seek essential guidance. |

| 2 | UNABLE to do this independently at present. Largely demonstrated by tutor. |

| 3 | UNABLE to do this independently at present but able to complete, to the required quality, with significant help, either procedural or by instruction. |

| 4 | ABLE to do this partially independently at the required quality but requires minor help with aspects of the skill, either procedural or through discussion. |

| 5 | ABLE to do this independently at the required quality. This may include confirmatory advice from the tutor where the student seeks appropriate assurance. |

| 6 | ABLE to meet the outcome independently, exceeding the required quality. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McKernon, S.L.; Adderton, E.A.; Dawson, L.J. Using Technology-Supported Approaches for the Development of Technical Skills Outside of the Classroom. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030329

McKernon SL, Adderton EA, Dawson LJ. Using Technology-Supported Approaches for the Development of Technical Skills Outside of the Classroom. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(3):329. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030329

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcKernon, Sarah L., Elliot A. Adderton, and Luke J. Dawson. 2024. "Using Technology-Supported Approaches for the Development of Technical Skills Outside of the Classroom" Education Sciences 14, no. 3: 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030329

APA StyleMcKernon, S. L., Adderton, E. A., & Dawson, L. J. (2024). Using Technology-Supported Approaches for the Development of Technical Skills Outside of the Classroom. Education Sciences, 14(3), 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030329