Culturally Responsive Middle Leadership for Equitable Student Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

The New Zealand Context

2. Middle Leaders Championing Change

3. Culturally Responsive Pedagogy

4. Methodology

Data Analysis

- How do you define Māori student success?

- What teaching practices make a positive difference for Māori students at your school? What works?

- What evidence do you have that these practices have made a positive difference? How do you know they work?

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bassett, M. The role of middle leaders in New Zealand secondary schools: Expectations and challenges. Waikato J. Educ. 2016, 21, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capper, C.A. The 20th-year anniversary of critical race theory in education: Implications for leading to eliminate racism. Educ. Adm. Q. 2015, 51, 791–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, J.P. Intersectionality, colonizing education and the Indigenous voice of survivance. In Intersectionality of Race, Ethnicity, Class and Gender in Teaching and Teacher Education: Movement Toward Equity in Education; Carter, N.P., Vavrus, M., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Agosto, V.; Roland, E. Intersectionality and educational leadership: A critical review. Rev. Res. Educ. 2018, 42, 255–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics and violence against women of color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, T. Theories of Educational Leadership and Management, 3rd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, M.; James, C.; Fertig, M. The difference between educational leadership and the importance of educational responsibility. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2019, 47, 504–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education Strategies and Policies. 2024. Available online: https://www.education.govt.nz/our-work/overall-strategies-and-policies/ (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Highfield, C.; Woods, R. Recent middle leadership research in secondary schools in New Zealand: 2015–2022. N. Z. J. Educ. Stud. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Berryman, M.; Eley, E. Succeeding as Māori: Māori students’ views on our stepping up to the Ka Hikitia challenge. N. Z. J. Educ. Stud. 2017, 52, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusche, D.; Laveault, D.; MacBeath, J.; Santiago, P. OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: New Zealand 2011; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Highfield, C. Management, Leadership and Governance of Secondary Education (New Zealand). In Bloomsbury Education and Childhood Studies; Mutch, C., Tatto, M., Eds.; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. What Boards Do. Available online: https://www.education.govt.nz/school/boards-information/boards-of-schools-and-kura/what-boards-do/ (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Ministry of Education. Education and Training Act 2020. Available online: https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2020/0038/latest/LMS170676.html (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Wylie, C.; MacDowall, S.; Ferral, H.; Fellgate, R.; Visser, H. Teaching Practices, School Practices and Principal Leadership: The First National Picture 2017; NZCER: Wellington, New Zealand, 2018; Available online: https://www.nzcer.org.nz/system/files/TSP_Summary.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Siskin, L. Realms of Knowledge: Academic Departments In Secondary Schools; Routledge Falmer Taylor and Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, T. Interrogating orthodox voices: Gender, ethnicity and educational leadership. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2003, 23, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, D.; Miller, D.; Gambling, M.; Gough, G.; Johnson, M. As others see us: Senior management and subject staff perceptions of the work effectiveness of subject leaders in secondary schools. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 1999, 19, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetaraka, M. Myth-making: Ongoing impacts of historical education policy on beliefs about Māori in education. N. Z. J. Educ. Stud. 2022, 57, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskins, T.K.; Tocker, K.; Jones, A. Discouraging children from speaking te reo in schools as a strategic Māori initiative. MAI J. 2020, 9, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, R. Teaching to the North-East: Relationship-Based Learning in Practice; NZCER Press: Wellington, New Zealand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rubie-Davies, C.M. Becoming a High Expectation Teacher: Raising the Bar; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rubie-Davies, C.M. Teacher Expectations in Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, H.; Rubie-Davies, C.; Webber, M. Teacher expectations, ethnicity and the achievement gap. N. Z. J. Educ. Stud. 2015, 50, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahuika, R.; Berryman, M.; Bishop, R. Issues of culture and assessment in New Zealand education pertaining to Māori students. Assess. Matters 2011, 3, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. Ka Hikitia—Ka Hāpaitia: The Māori Education Strategy. Available online: https://www.education.govt.nz/our-work/overall-strategies-and-policies/ka-hikitia-ka-hapaitia/ka-hikitia-ka-hapaitia-the-maori-education-strategy/ (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Liu, S.; Hallinger, P. Principal instructional leadership, teacher self-efficacy and teacher professional learning in China: Testing a mediated-effects model. Educ. Adm. Q. 2018, 54, 501–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K. Department head leadership for school improvement. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2016, 15, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadok, A.; Benoliel, P. Middle-leaders’ transformational leadership: Big five traits and teacher commitment. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2023, 37, 810–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Jones, M.; Ismail, N.; Nguyen, D. Middle leaders and middle leadership in schools: Exploring the knowledge base (2003–2017). Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2019, 39, 255–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Riggio, R.E. Transformational Leadership, 2nd ed.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C.; Schon, D.A. Theory in Practice: Increasing Professional Effectiveness; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Breunig, M. Turning experiential education and critical pedagogy theory into praxis. J. Exp. Educ. 2005, 28, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergiovanni, T.J.; Starratt, R.J. Supervision Human Perspectives, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Carrington, S. Inclusion needs a different school culture. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 1999, 3, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory Pract. 1995, 34, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1995, 32, 465–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, G. Culturally responsive teaching in special education for ethnically diverse students: Setting the stage. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2002, 15, 613–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, G. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2nd ed.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Highfield, C.; Webber, M. Mana ūkaipō: Enhancing Māori engagement through pedagogies of connection and belonging. N. Z. J. Educ. Stud. 2021, 56, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, E.M.; Webber, M. Whāia te ara whetu: Navigating change in mainstream secondary schooling for Indigenous students. In Handbook of Indigenous Education; Smith, L., McKinley, E., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2018; pp. 1049–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penetito, W. Place-based education: Catering for curriculum, culture and community. N. Z. Annu. Rev. Educ. 2008, 18, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, M.; O’Connor, K. A fire in the belly of Hineāmaru: Using whakapapa as a pedagogical tool in education. Genealogy 2019, 3, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. Tū Rangatira: Māori Medium Educational Leadership; Huia Publishers: Wellington, New Zealand, 2010.

- Ministry of Education. Tātaiako: Cultural Competencies for Teaching Māori Learners; Ministry of Education: Wellington, New Zealand, 2011.

- Ministry of Education. Leading from the Middle—Educational Leadership for Middle and Senior Leaders; Learning Media Ltd.: Wellington, New Zealand, 2012.

- Ministry of Education. Ka Hikitia—Accelerating Success: The Māori Education Strategy 2013–2017; Ministry of Education: Wellington, New Zealand, 2013.

- Highfield, C.; Rubie-Davies, C. Middle leadership practices in secondary schools associated with improved student outcomes. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2022, 42, 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L. Culturally responsive leadership for community empowerment. Multicult. Educ. Rev. 2014, 6, 145–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.P.; Bottiani, J.H.; Bradshaw, C.P. Teachers’ structuring of culturally responsive social relations and secondary students’ experience of warm demand. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2023, 76, 102241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. The Future of Jobs Report 2023. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-of-jobs-report-2023/ (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Walkey, F.H.; McClure, J.; Meyer, F.; Weir, K.P. Low expectations equal no expectations: Aspirations, motivation and achievement in secondary school. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 38, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, O.; Wildy, H.; Shand, J. A grounded theory about how teachers communicated high expectations to their secondary school students. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2023, 39, 211–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabach, D.B.; Suárez-Orozco, C.; Hernandez, S.J.; Brooks, M.D. Future perfect? Teachers’ expectations and explanations of their Latino immigrant students’ postsecondary futures. J. Lat. Educ. 2018, 17, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, H.; Bosker, R.J.; van der Werf, M.P. Sustainability of teacher expectation bias effects on long-term student performance. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 102, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKown, C.; Weinstein, R.S. Modelling the role of child ethnicity and gender in children’s differential response to teacher expectations. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 159–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubie-Davies, C.M.; Hattie, J.; Hamilton, R. Expecting the best for students: Teacher expectations and academic outcomes. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 76, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutou, T. Kia Tū Rangatira Ai Survey; Unpublished Project Survey; University of Auckland: Auckland, New Zealand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stats, N.Z. Functional Urban Areas—Methodology and Classification. Available online: https://www.stats.govt.nz/methods/functional-urban-areas-methodology-and-classification (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Ministry of Education. Ministry Funding Deciles. Available online: https://parents.education.govt.nz/primary-school/schooling-in-nz/ministry-funding-deciles/ (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology: Vol. 2 Research Designs; Cooper, H., Camic, P.M., Long, D.L., Panter, A.T., Rindskopf, D., Sher, K.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Zealand Qualifications Authority. University Entrance. Available online: http://www.nzqa.govt.nz/qualifications-standards/awards/university-entrance/ (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- New Zealand Qualifications Authority. Report on 2020 NCEA, UE and NZ Scholarship Data and Statistics. Available online: https://www2.nzqa.govt.nz/about-us/news/report-on-2020-ncea-ue-and-nz-scholarship/ (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Bishop, R.; Berryman, M.; Wearmouth, J. Te Kotahitanga: Towards Effective Education Reform for Indigenous and Other Minoritised Students; NZCER Press: Wellington, New Zealand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hynds, A.; Meyer, L.H.; Penetito, W.; Averill, R.; Hindle, R.; Taiwhati, M.; Hodis, F.; Faircloth, S. Evaluation of He Kākano: Professional Development for Leaders in Secondary Schools (2011–2012): Final Report; Ministry of Education: Wellington, New Zealand, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. Kia Eke Panuku—Building on Success. Available online: https://nzcurriculum.tki.org.nz/System-of-support-incl.-PLD/School-initiated-supports/Professional-learning-and-development/Kia-Eke-Panuku-Building-on-Success (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Highfield, C.; Webber, M.; Woods, R. Te pā harakeke: Māori and non-Māori parent (whānau) support of culturally responsive teaching pedagogies. Aust. J. Indig. Educ. 2023, 52, 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulruf, B.; Hattie, J.; Tumen, S. The predictability of enrolment and first-year university results from secondary school performance: The New Zealand National Certificate of Educational Achievement. Stud. High. Educ. 2008, 33, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Timperley, H. Potential chokepoints in the National Certificate of Educational Achievement for attaining university entrance. N. Z. J. Educ. Stud. 2008, 43, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Webber, M.; Eaton, J.; Cockle, V.; Linley-Richardson, T.; Rangi, M.; O’Connor, K. Starpath Phase Three—Final report. Starpath Project; The University of Auckland: Auckland, New Zealand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Education Review Office. Education for All Our Children: Embracing Diverse Ethnicities. Available online: https://ero.govt.nz/our-research/education-for-all-our-children-embracing-diverse-ethnicities (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Davies, M.J.; Davies, M.; Foreman-Brown, G. Secondary teachers’ beliefs about the relationship between students’ cultural identity and their ability to think critically. J. Pedagog. Res. 2023, 7, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. Māori Language in Schooling. Available online: https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/maori-language-in-schooling (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Ministry of Education. Tau Mai Te Reo. Available online: https://www.education.govt.nz/our-work/overall-strategies-and-policies/tau-mai-te-reo/ (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Higgins, R. (7 July 2015). Ki wīwī, ki wāwā– Normalising the Māori Language. Inaugural Lecture, Victoria University of Wellington. Available online: https://www.wgtn.ac.nz/news/2015/07/importance-of-te-reo-revitalisation-highlighted (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Devine, N.; Stewart, G.T.; Couch, D. Including Māori language and knowledge in every New Zealand classroom. N. Z. J. Educ. Stud. 2021, 65, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seashore Louis, K.; Robinson, V. External mandates and instructional leadership: School leaders as mediating agents. J. Educ. Adm. 2012, 50, 629–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills Brown, M.; Williams, F.K. Culturally responsive leadership preparation and practices. In Handbook of Urban Educational Leadership; Khalifa, M.A., Witherspoon, A.N., Osanloo, D.A.F., Grant, C.M., Eds.; Rowan & Littlefield: Lanham, ML, USA, 2015; pp. 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Sinnema, C.; Meyer, F.; Le Fevre, D.; Chalmers, H.; Robinson, V.J. Educational leaders’ problem-solving for educational improvement: Belief validity testing in conversations. J. Educ. Change 2023, 24, 133–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, M.; Braun, A.; Ball, S. Where you stand depends on where you sit: The social construction of policy enactments in the (English) secondary school. Discourse Abingdon 2015, 36, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skerritt, C.; McNamara, G.; Quinn, I.; O’Hara, J.; Brown, M. Middle leaders as policy translators: Prime actors in the enactment of policy. J. Educ. Policy 2023, 38, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagno, A.E. (Ed.) The Price of Nice: How Good Intentions Maintain Educational Inequity; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A.J.; Thompson, P. Leading for success in flexi schools. Lead. Manag. J. Aust. Counc. Educ. Lead. 2023, 29, 64–74. [Google Scholar]

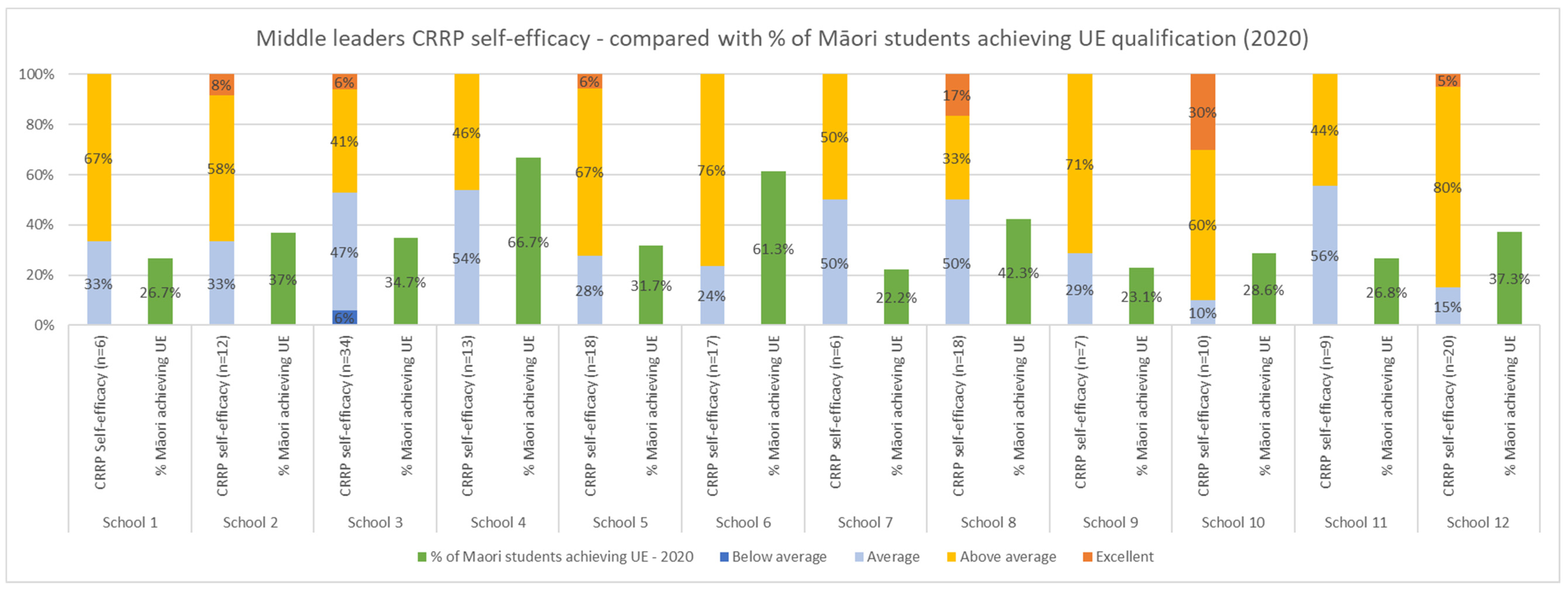

| School | Decile | % of Māori | # of ML Respondents | UE Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 54% | 6 | 26.7% |

| 2 | 5 | 20% | 12 | 33% |

| 3 | 7 | 18% | 34 | 34.7% |

| 4 | 8 | 14% | 13 | 66.7% |

| 5 | 6 | 30% | 18 | 31.7% |

| 6 | 6 | 27% | 17 | 61.3% |

| 7 | 5 | 39% | 6 | 22.2% |

| 8 | 4 | 53% | 18 | 42.3% |

| 9 | 4 | 55% | 7 | 23.1% |

| 10 | 7 | 18% | 10 | 28.6% |

| 11 | 5 | 40% | 9 | 26.8% |

| 12 | 5 | 40% | 20 | 37.3% |

| Gender | Main Ethnicity | Years Spent Teaching | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | Other | Pākehā | Māori | Pasifika 1 | Asian | Other | 3–8 | 9–14 | 15–20 | 21+ | ||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | ||

| Gender | M | 41.8 (71) | 39.2 (58) | 54.5 (6) | 66.7 (2) | 50 (2) | 75 (3) | 32.3 (10) | 48.5 (16) | 39.1 (18) | 45 (27) | ||

| F | 57 (97) | 59.4 (88) | 45.5 (5) | 33.3 (1) | 50 (2) | 25 (1) | 67.7 (21) | 48.5 (16) | 60.9 (28) | 53.3 (32) | |||

| Other | 1.2 (2) | 1.4 (2) | 3 (1) | 1.7 (1) | |||||||||

| Main ethnicity | Pākehā | 81.7 (58) | 90.7 (88) | 100 (2) | 87 (148) | 83.9 (26) | 87.9 (29) | 86.9 (40) | 88.4 (53) | ||||

| Māori | 8.5 (6) | 5.2 (5) | 6.4 (11) | 12.9 (4) | 6.1 (2) | 6.5 (3) | 3.3 (2) | ||||||

| Pasifika | 2.8 (2) | 1 (1) | 1.8 (3) | 2.2 (1) | 3.3 (2) | ||||||||

| Asian | 2.8 (2) | 2.1 (2) | 2.4 (4) | 3 (1) | 2.2 (1) | 3.3 (2) | |||||||

| Other | 4.2 (3) | 1 (1) | 2.4 (4) | 3.2 (1) | 3 (1) | 2.2 (1) | 1.7 (1) | ||||||

| Years spent teaching | 3–8 | 14.1 (10) | 21.6 (21) | 17.6 (26) | 36.4 (4) | 25 (1) | 18.2 (31) | ||||||

| 9–14 | 22.5 (16) | 16.5 (16) | 50 (1) | 19.6 (29) | 18.2 (2) | 25 (1) | 25 (1) | 19.4 (33) | |||||

| 15–20 | 25.4 (18) | 28.9 (28) | 27 (40) | 27.2 (3) | 33.3 (1) | 25 (1) | 25 (1) | 27.1 (46) | |||||

| 21+ | 38 (27) | 33 (32) | 50 (1) | 35.8 (53) | 18.2 (2) | 66.7 (2) | 50 (2) | 25 (1) | 35.3 (60) | ||||

| Survey Statement | % Middle Leaders (n = 170) |

|---|---|

| I ensure Māori students feel strong and safe in their cultural identity | 84 |

| I know when Māori students are achieving | 91 |

| Māori whānau (families) are made to feel welcome in my classroom | 77 |

| I treat Māori whānau (families) and Māori culture with respect | 98 |

| Māori whānau (families) are provided with opportunities to share their knowledge and experiences in my classroom | 56 |

| Māori students have multiple opportunities to succeed in my classroom | 92 |

| In my classroom, I know my Māori students and they know me | 88 |

| In my classroom, I respect the Māori students and they respect me | 95 |

| In my classroom, Māori students feel cared for | 94 |

| I know and teach the Māori history associated with where my school is based (e.g., hapū/iwi [tribal/local Māori] history) | 31 |

| Theme | Coded Responses | % of ML Comments (n = 170) |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion of culture and language 32% | Affirming/acknowledging culture | 11% |

| CRP—connect culture to learning | 12% | |

| Learn and use te reo to normalise use in the classroom | 5% | |

| Pronunciation of te reo and names | 4% | |

| Specific teacher actions/pedagogy 59% | Create positive relationships/get to know student/take an interest | 23% |

| Differentiated learning/assessment | 11% | |

| Be consistent/positive feedback/caring/patient/listen/use humour | 8% | |

| High expectations | 5% | |

| Respect student/believe in student/celebrate success | 5% | |

| One-on-one assistance | 3% | |

| Build a safe/inclusive learning environment for all/sense of belonging/feeling comfortable | 2% | |

| Set clear boundaries | 2% | |

| Whānau involvement 4% | Whānau connection/partnership | 4% |

| No response 5% | Blank or “I don’t know” | 5% |

| Theme | How Do You Define Māori Student Success? | % ML Comments (n = 170) |

|---|---|---|

| Achieving Success 46.4% | Academic, e.g., grades/NCEA credits | 24.0% |

| Holistic or general success, e.g., meeting own goals/pride in self/well-being | 19.6% | |

| Student is future-focused | 2.8% | |

| Student engagement factors 37.4% | Student feels comfortable in class and school/confident | 13.1% |

| Student is striving to be best they can be | 5.0% | |

| Student is engaged/enjoying school | 16.2% | |

| Student has positive relationships/leadership capability | 3.1% | |

| Cultural factors 10.6% | Student is proud of their culture | 2.2% |

| Māori students achieving success as Māori | 8.4% | |

| No response 5.6% | Blank or “I don’t know” | 5.6% |

| Theme | Coded Responses | % of ML Comments (n = 170) |

|---|---|---|

| Student experiencing success 29.4% | Academic success or progress/grades | 20.4% |

| Holistic success | 9% | |

| Student engagement 47.1% | Positive attitude/engagement | 23.9% |

| Improved attendance | 4.2% | |

| Students showing pride in culture/connecting culture to learning | 4.8% | |

| Positive student feedback | 14.2% | |

| Positive relationships 15.6% | Student–teacher relationship | 10.7% |

| Whānau connection/partnership | 4.8% | |

| No response 8% | Blank or “I don’t know” | 8% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Highfield, C.; Webber, M.; Woods, R. Culturally Responsive Middle Leadership for Equitable Student Outcomes. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 327. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030327

Highfield C, Webber M, Woods R. Culturally Responsive Middle Leadership for Equitable Student Outcomes. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(3):327. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030327

Chicago/Turabian StyleHighfield, Camilla, Melinda Webber, and Rachel Woods. 2024. "Culturally Responsive Middle Leadership for Equitable Student Outcomes" Education Sciences 14, no. 3: 327. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030327

APA StyleHighfield, C., Webber, M., & Woods, R. (2024). Culturally Responsive Middle Leadership for Equitable Student Outcomes. Education Sciences, 14(3), 327. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030327