“Bye-Bye Germs”: Respiratory Tract Infection Prevention—An Education Intervention for Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Does the Germ’s Journey educational workshop increase children’s understanding of pathogens and respiratory tract illness?

- Does the Germ’s Journey educational workshop give children a greater understanding of pathogen transmission?

- Does the Germ’s Journey educational workshop improve children’s understanding of infection prevention methods?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instrumentation

2.2.1. Pre- and Post-Questions to Assess Children’s Learning

2.2.2. Semi-Structured Interviews with Teachers

2.3. Procedure—Pedagogic Learning Design

2.3.1. Intervention Workshop Activities

2.3.2. Whole-Class Activities

2.3.3. Carousel Activities

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

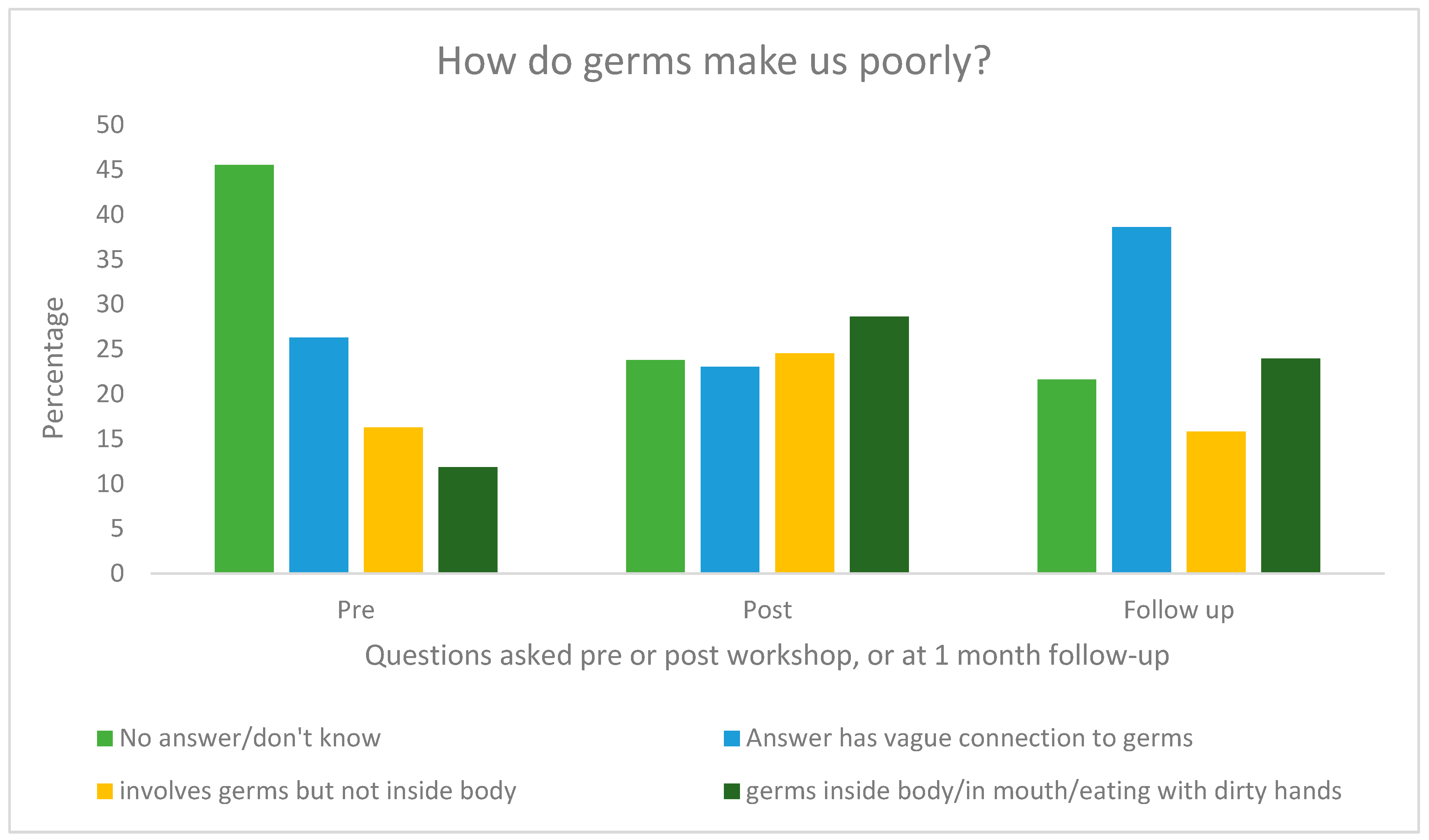

3.1. Children’s Understanding of Pathogens and Transmission

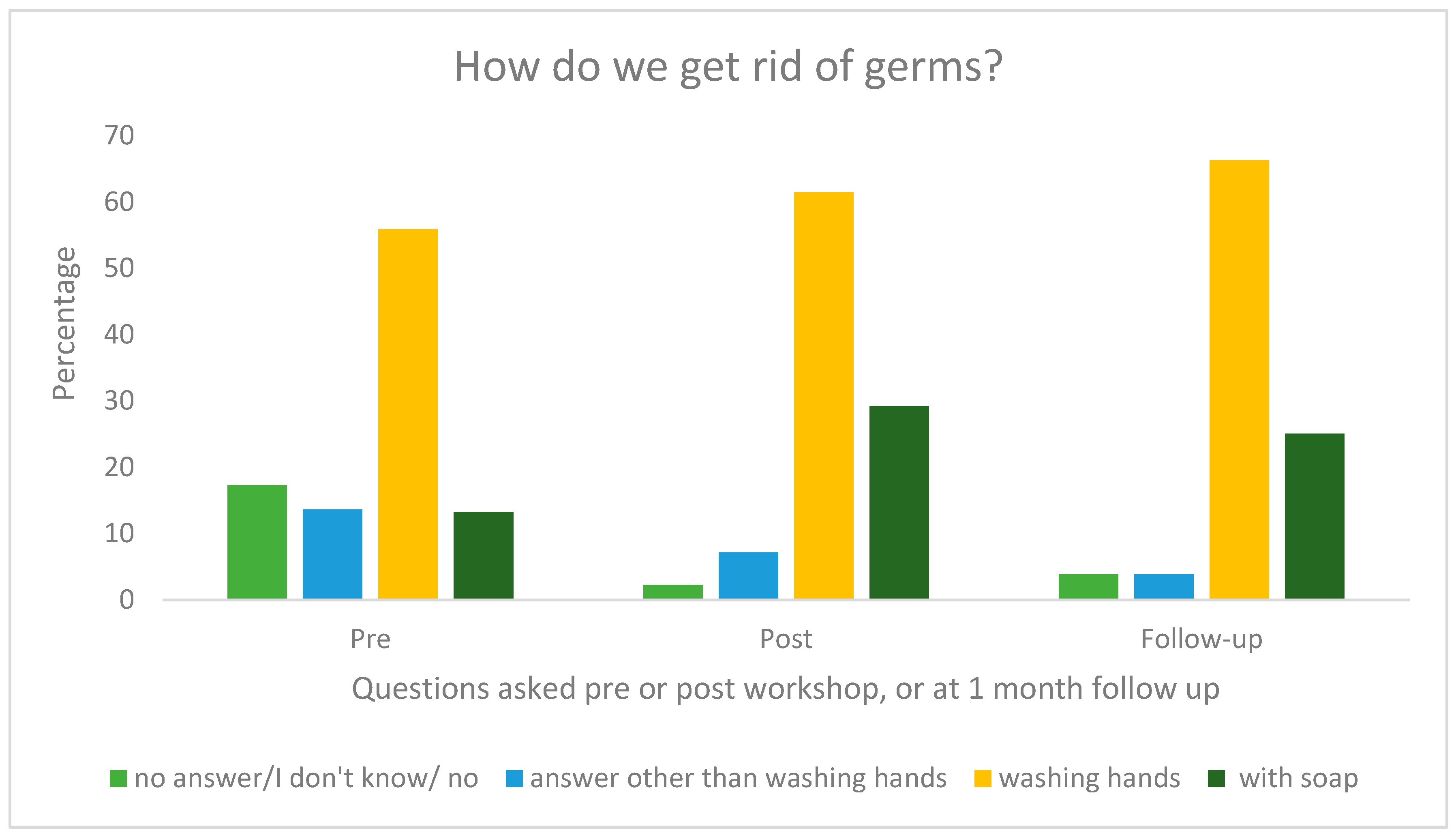

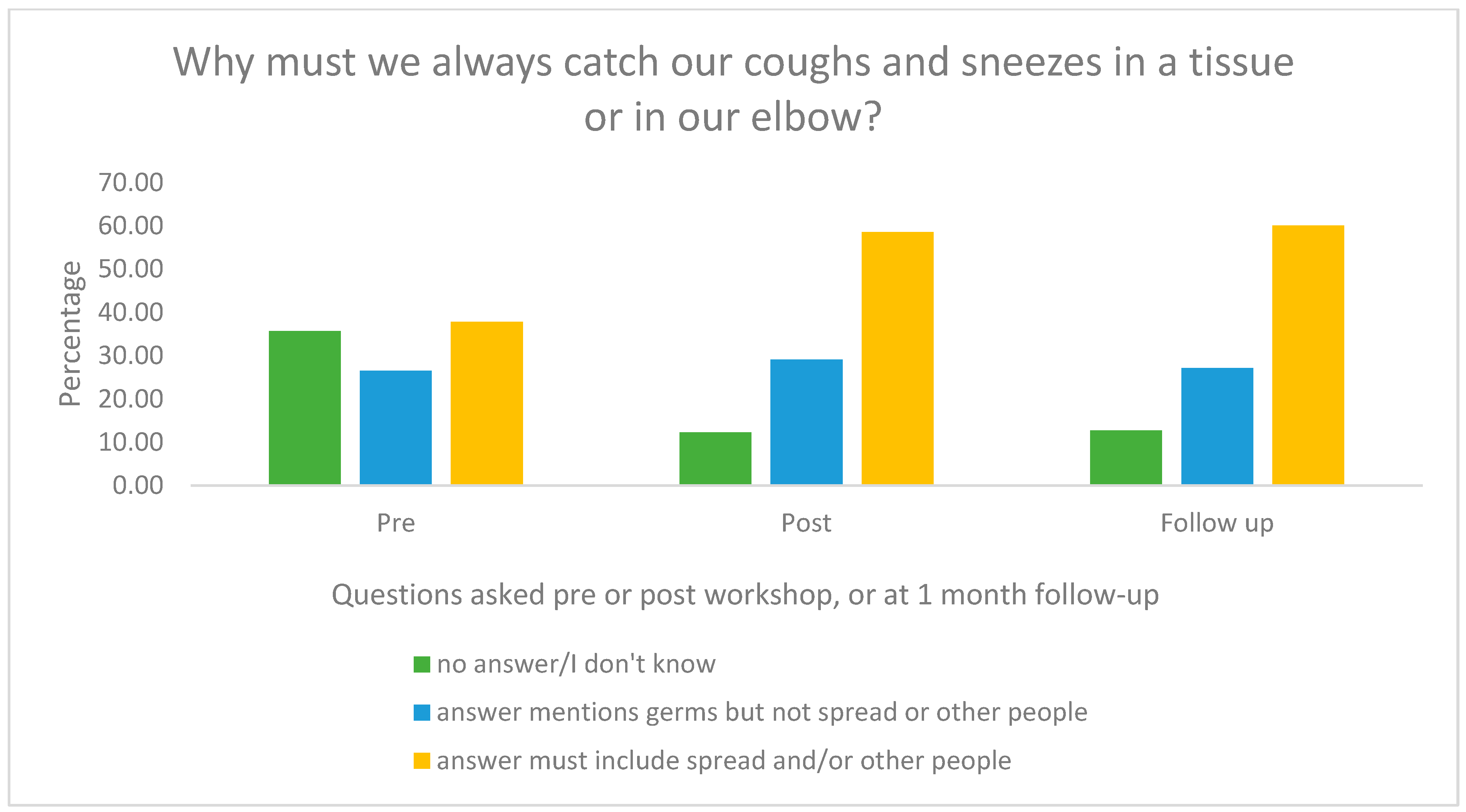

3.2. Children’s Understanding of Respiratory Tract Illness and Infection Prevention Methods

3.3. Teachers’ Semi-Structured Interview Findings

3.3.1. Abstract Concepts—Invisible Pathogens

3.3.2. Embedding the Topic of Infection Prevention from an Early Age

3.3.3. Behavioural Change

4. Discussion

4.1. Children’s Understanding of Pathogens and Transmission

4.2. Children’s Understanding of Respiratory Tract Illness and Infection Prevention Methods

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Workshop Brief/Lesson Plan for Teachers

| Activity | Description | Length |

|---|---|---|

| Book Reading | The whole class will sit and watch a video of the book’s illustrator reading the Bye Bye Germs book. | 10 m |

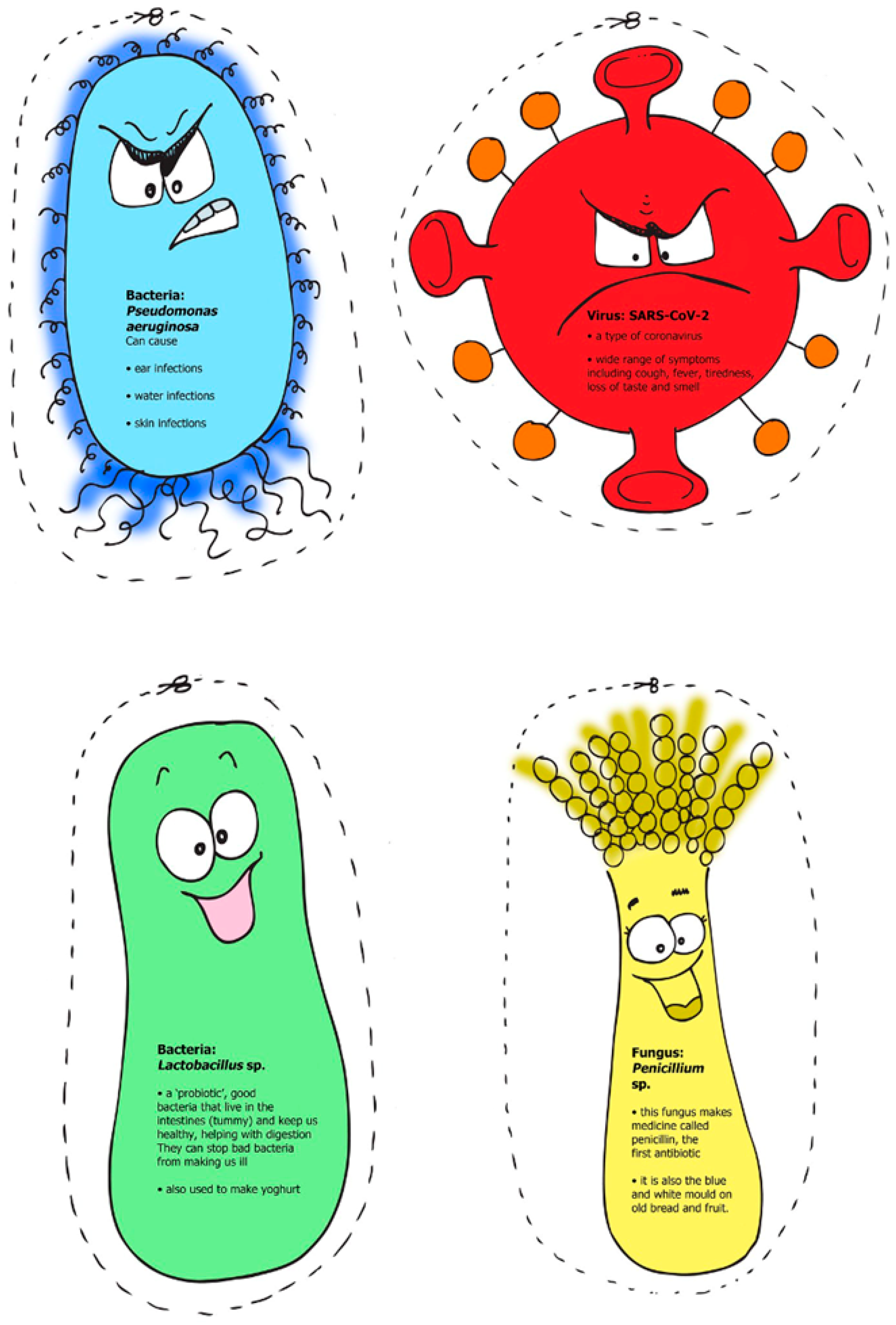

| Hunt the Germ | Cartoon images of bacteria and viruses with faces to be hidden around the classroom. Children hunt in groups to find a picture of the hidden germ and come back as a whole class with the picture when they have found one. Germs will be either “good” or “bad” and the leader will read the fact about the germ and discuss with the children why they’re either “good” or “bad”. | 10 m |

| Giant Germs | Following on from the previous activity, the leader, using attractive-looking microbe plush toys, will explain how invisible germs on hands and in coughs and sneezes can be spread all around us. Germs come in all shapes and sizes but are all very small and can only be seen with special equipment. We will use giant microbe toys to show variations in germs (SARS-CoV-1 and -2, Pseudomonas, Staph aureus and MRSA). The activity will discuss bacteria and viruses and “good” and “bad” germs. Good germs help us to make bread, yoghurt and medicine. Some good germs live inside us to help us to digest our food, and they can stop bad germs. Bad germs make us feel ill. Bacteria can live outside the body; viruses must be right inside us before they can make more viruses. | 5–10 Total: 25–30 m |

| Activity | Description | Length |

|---|---|---|

| Draw a Germ | Video tutorial. The artist of the book teaches children how to draw their own versions of the germs in the book, with the children drawing as they are taught. | 10 m |

| Pepper in bowl and Paint on Gloves | (a) Video/demonstration: a large bowl of water with pepper flakes and a separate bowl of soap so children can try for themselves. (b) Video/demonstration of correct handwashing using paint on gloves: which bits of the hands have been missed? Children will mimic hand actions during with the demonstration. | 10 m |

| Glo-Gel | Children cover their hands with glo-gel (“germs”), see “germs” under an ultraviolet lamp, wash their hands and check to see how much gel is still visible. Children are told the correct way to wash their hands in order to remove the gel/germs. | 10 m |

| Cut and Stick | A worksheet including a classroom scene, in which children cut and stick pictures of germs and place them in areas of a classroom scene where they think the germs are “hiding”. Children can instead circle the areas in the classroom scene, rather than cutting and sticking, if preferred. | 10 m Total: 40 m |

References

- Government UK. Build Back Better: Our Plan for Growth. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/build-back-better-our-plan-for-growth (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- Behl, A.; Nair, A.; Mohagaonkar, S.; Yadav, P.; Gambhir, K.; Tyagi, N.; Sharma, R.K.; Butola, B.S.; Sharma, N. Threat, challenges, and preparedness for future pandemics: A descriptive review of phylogenetic analysis based predictions. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2022, 98, 105217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D. What do We Know about COVID-19 and Children? BMJ 2023, 380. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/380/bmj.p21 (accessed on 29 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M.D.; Escobar, G.J.; Lu, Y.; Schlessinger, D.; Steinman, J.B.; Steinman, L.; Lee, C.; Liu, V.X. Risk of Severe COVID-19 Infection among Adults with Prior Exposure to Children. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2204141119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, S. Massachusetts General Hospital Researchers Show Children Are Silent Spreaders of Virus That Causes COVID-19. Massachusetts General Hospital. 2020. Available online: https://www.massgeneral.org/news/press-release/massachusetts-general-hospital-researchers-show-children-are-silent-spreaders-of-virus-that-causes-covid-19 (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- Mohanty, M.C.; Taur, P.D.; Sawant, U.P.; Yadav, R.M.; Potdar, V. Prolonged fecal shedding of SARS-CoV-2 in asymptomatic children with inborn errors of immunity. J. Clin. Immunol. 2021, 41, 1748–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Odd, D.; Harwood, R.; Ward, J.; Linney, M.; Clark, M.; Hargreaves, D.; Ladhani, S.N.; Draper, E.; Davis, P.J.; et al. Deaths in children and young people in England after SARS-COV-2 infection during the first pandemic year. Nat. Med. 2021, 28, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, J.L.; Harwood, R.; Smith, C.; Kenny, S.; Clark, M.; Davis, P.J.; Draper, E.S.; Hargreaves, D.; Ladhani, S.; Linney, M.; et al. Risk factors for PICU admission and death among children and young people hospitalized with COVID-19 and pims-TS in England during the first Pandemic Year. Nat. Med. 2021, 28, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, J.M.; Pittet, D. Guideline for hand hygiene in health-care settings: Recommendations of the healthcare infection control practices advisory committee and the HICPAC/Shea/apic/idsa hand hygiene task force. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 2002, 23, S3–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care. 2009. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241597906 (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Department of Health and Social Care. Public Information Campaign Focuses on Handwashing. GOVERNMENT.UK. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/public-information-campaign-focuses-on-handwashing (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Allegranzi, B.; Tartari, E.; Pittet, D. ‘Seconds save lives—Clean your hands’: The 5 may 2021 World Health Organization’s Save Lives: Clean Your Hands Campaign. Int. J. Infect. Control. 2021, 17, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, A.E.; Coulborn, R.M.; Perez, V.; Larson, E.L. Effect of Hand Hygiene on Infectious Disease Risk in the Community Setting: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 1372–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren-Gash, C.; Fragaszy, E.; Hayward, A.C. Hand hygiene to reduce community transmission of influenza and acute respiratory tract infection: A systematic review. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2012, 7, 738–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.M.; Chakraborty, R.; Brown, S.; Sultana, R.; Colon, A.; Toor, D.; Upreti, P.; Sen, B. Association between handwashing behavior and infectious diseases among low-income community children in Urban New Delhi, India: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luby, S.P.; Agboatwalla, M.; Feikin, D.R.; Painter, J.; Billhimer, W.; Altaf, A.; Hoekstra, R.M. Effect of handwashing on Child health: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005, 366, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randle, J.; Metcalfe, J.; Webb, H.; Luckett, J.; Nerlich, B.; Vaughan, N.; Segal, J.; Hardie, K. Impact of an educational intervention upon the hand hygiene compliance of children. J. Hosp. Infect. 2013, 85, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittleborough, C.R.; Nicholson, A.L.; Young, E.; Bell, S.; Campbell, R. Implementation of an educational intervention to improve hand washing in primary schools: Process evaluation within a randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.; Dreibelbis, R.; Aunger, R.; Deola, C.; King, K.; Long, S.; Chase, R.P.; Cumming, O. Child’s play: Harnessing play and curiosity motives to improve child handwashing in a humanitarian setting. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2019, 222, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, B.; Rebar, A.L. Habit formation and behavior change. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fináncz, J.; Podráczky, J.; Deutsch, K.; Soós, E.; Bánfai-Csonka, H.; Csima, M. Health Education Intervention Programs in Early Childhood Education: A Systematic Review. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Investing in High-Quality Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC). 2012. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/school/48980282.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- Vandenbroeck, M.; Lenaerts, K.; Beblavý, M. Benefits of Early Childhood Education and Care and the Conditions for Obtaining Them; EENEE Analytical Report No. 32. Prepared for the European Commission; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/20810 (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- Ansari, A.; Pianta, R.C.; Whittaker, J.V.; Vitiello, V.E.; Ruzek, E.A. Starting Early: The Benefits of Attending Early Childhood Education Programs at Age 3. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 56, 1495–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaeta, M.L.; Cavazos, J.; Cabrera, M.d.R.; Rosário, P. Fostering Oral Hygiene Habits and Self-Regulation Skills: An Intervention With Preschool Children. Fam. Community Health 2018, 41, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fastring, D.; Keel, K.; Colby, D.; Conner, J.M.; Hilbert, A. Head Start Centers Can Influence Healthy Behaviors: Evaluation of a Nutrition and Physical Activity Educational Intervention. J. Sch. Health 2019, 89, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, J.; Kim, G.; Lim, H.; Carvajal, N.A.; Lloyd, C.W.; Wang, Y. A kindergarten-based child health promotion program: The Adapted National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Mission X for improving physical fitness in South Korea. Glob. Health Promot. 2019, 26, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Dwyer, M.V.; Fairclough, S.J.; Ridgers, N.D.; Knowles, Z.R.; Foweather, L.; Stratton, G. Effect of a school-based active play intervention on sedentary time and physical activity in preschool children. Health Educ. Res. 2013, 28, 931–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.E.; Palmer, K.K.; Webster, E.K.; Logan, S.W.; Chinn, K.M. The Effect of CHAMP on Physical Activity and Lesson Context in Preschoolers: A Feasibility Study. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 2018, 89, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga-Pontes, C.; Simões-Dias, S.; Lages, M.; Guarino, M.P.; Graça, P. Nutrition education strategies to promote vegetable consumption in preschool children: The Veggies4myHeart project. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Droog, S.M.; Buijzen, M.; Valkenburg, P.M. Enhancing children’s vegetable consumption using vegetable-promoting picture books. The impact of interactive shared reading and character-product congruence. Appetite 2014, 73, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindler, J.M.; Corbett, D.; Forestell, C.A. Assessing the effect of food exposure on children’s identification and acceptance of fruit and vegetables. Eat. Behav. 2013, 14, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kobel, S.; Wirt, T.; Schreiber, A.; Kesztyüs, D.; Kettner, S.; Erkelenz, N.; Wartha, O.; Steinacker, J.M. Intervention Effects of a School-Based Health Promotion Programme on Obesity Related Behavioural Outcomes. J. Obes. 2014, 2014, 476230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornilaki, E.N.; Skouteris, H.; Morris, H. Developing connections between healthy living and environmental sustainability concepts in Cretan preschool children: A randomized trial. Early Child Dev. Care 2021, 192, 1685–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, A.E.; Hennink-Kaminski, H.; Moore, R.; Burney, R.; Chittams, J.L.; Parker, P.; Luecking, C.T.; Hales, D.; Ward, D.S. Evaluating a child care-based social marketing approach for improving children’s diet and physical activity: Results from the Healthy Me, Healthy We cluster-randomized controlled trial. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 7, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiseman, N.; Harris, N.; Lee, P. Lifestyle knowledge and preferences in preschool children: Evaluation of the Get up and Grow healthy lifestyle education programme. Health Educ. J. 2016, 75, 1012–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, S.; Laird, K.; Younie, S. Interactive Health-Hygiene Education for Early Years: The Creation and Evaluation of Learning Resources to Improve Understanding of Handwashing Practice. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2019, 27, 374–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, S.; Laird, K.; Younie, S. Children and Handwashing: Developing a Resource to Promote Health and Well-Being in Low and Middle Income Countries. Health Educ. J. 2019, 79, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, S.; Younie, S.; Williamson, I.; Laird, K. Evaluating Approaches to Designing Effective Co-Created Hand-Hygiene Interventions for Children in India, Sierra Leone and the UK. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younie, S.; Mitchell, C.; Bisson, M.-J.; Crosby, S.; Kukona, A.; Laird, K. Improving Young Children’s Handwashing Behaviour and Understanding of Germs: The Impact of a Germ’s Journey Educational Resources in Schools and Public Spaces. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, L. The benefits and challenges of multisite studies. AACN Adv. Crit. Care 2009, 20, 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, E.K.; Slemon, A.; Haines-Saah, R.J.; Oliffe, J. A guide to multisite qualitative analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2018, 28, 1969–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DfE. The National Curriculum in England; Department for Education: London, UK, 2013.

- DfE. Statutory Guidance: Physical Health and Mental Wellbeing (Primary and Secondary). GOVERNMENT.UK. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/relationships-education-relationships-and-sex-education-rse-and-health-education/physical-health-and-mental-wellbeing-primary-and-secondary (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Bruner, J. The Process of Education; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Thought and Language; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Pearson FT Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, N.; Danechi, S. Coronavirus and Schools—House of Commons Library. Coronavirus and Schools. 2022. Available online: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8915/ (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Rotter Julian, B. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 1966, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, M.; Younie, S. Education for All in Times of Crisis—Lessons from COVID-19; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Church of England Academy Trust | Community School | Community School | Community School | Roman Catholic Academy Trust | England National Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Ages | 4–11 | 3–11 | 3–11 | 3–11 | 3–11 | |

| No. of pupils | 207 | 462 | 707 | 487 | 249 | |

| No. of groups in Year 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Class size | 28 | 3 × 30 | 3 × 30 | 2 × 30 | 25 | |

| SEN support | 5.6% | 6.7% | 8.3% | 13.4% | 30.9% | 14.6% |

| Free School Meals | 7.9% | 3.7% | 15.3% | 44.1% | 43.4% | 23.5 |

| Not English first language | 9.3% | 3.2% | 97.2% | 30% | 36.9% | 20.9% |

| OFSTED | 2016: Good | 2018: Good | 2017: Good | 2014: Outstanding | 2018: requires improvement | |

| ** Index of multiple deprivation Score (2019) | 29,438 D9 | 32,607 D10 | 9221 D3 | 5039 D2 | 5112 D2 |

| Question: | Individual Score Criteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 1: “How do germs make us poorly?” | Child said, “I don’t know,” did not give an answer or gave an answer that did not involve germs or handwashing | Answers had a connection to germs or hand washing | Answer involved germs or not washing hands, but did not state “inside body” | Answers that included “inside body”, “in mouth”, and/or “eating with dirty hands” |

| 2: “Where do germs live?” | Child said “I don’t know” or gave no answer | Child suggested an area that could be contaminated | N/A | N/A |

| 3: “Can we get germs from coughs and sneezes?” | Child answered “no” | Child answered “yes” | N/A | N/A |

| 4: “How do we get rid of germs?” | Child said “I don’t know” or gave no answer | Child gave an answer other than “washing hands” | Answer included washing hands | Answer included “washing hands with soap” |

| 5: “Why must we always catch our coughs and sneezes in a tissue or in our elbow?” | Child said “I don’t know” or gave no answer | Answer mentions germs but does not mention the spread/transmission of germs or other people | Answer included the spread of germs to other people | N/A |

| Pupils’ Answers | Score | Pre | Post | Follow-Up | % Change between Pre- and Post-Workshop | % Change Between Pre-Workshop and Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No answer/did not know | 0 | 43.59% (119) | 10.82% (29) | 12.31% (32) | 32.77% decrease | 31.28% decrease |

| Answer includes contaminated areas | 1 | 56.41% (154) | 89.18% (239) | 87.69% (228) | 32.77% increase | 31.28% increase |

| Pupils’ Answers | Score | Pre-Workshop | Post-Workshop | Follow-Up | % Change between Pre- and Post-Workshop | % Change between Pre-Wokshop and Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | 0 | 18.79% (28) | 10.97% (17) | 13.42% (20) | 7.82% decrease | 5.37% decrease |

| Yes | 1 | 81.21% (121) | 89.03% (155) | 86.58% (129) | 7.82% increase | 5.37% increase |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Younie, S.; Crosby, S.; Firth, C.; McNicholl, J.; Laird, K. “Bye-Bye Germs”: Respiratory Tract Infection Prevention—An Education Intervention for Children. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030302

Younie S, Crosby S, Firth C, McNicholl J, Laird K. “Bye-Bye Germs”: Respiratory Tract Infection Prevention—An Education Intervention for Children. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(3):302. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030302

Chicago/Turabian StyleYounie, Sarah, Sapphire Crosby, Charlie Firth, Johanna McNicholl, and Katie Laird. 2024. "“Bye-Bye Germs”: Respiratory Tract Infection Prevention—An Education Intervention for Children" Education Sciences 14, no. 3: 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030302

APA StyleYounie, S., Crosby, S., Firth, C., McNicholl, J., & Laird, K. (2024). “Bye-Bye Germs”: Respiratory Tract Infection Prevention—An Education Intervention for Children. Education Sciences, 14(3), 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030302