The Mental Well-Being and Inclusion of Refugee Children: Considerations for Culturally Responsive Trauma-Informed Therapy for School Psychologists

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.1.1. Migration Experiences That Trigger Poor Mental Health

1.1.2. Rates of Mental Health Difficulties Refugee Children

1.2. Framework: Culturally Responsive Therapy

- CRT requires cultural humility: It compels therapists to reflect on their cultural biases and practice cultural flexibility and humility. Cultural flexibility and humility are the attitudes that precede the practice of CRT. Cultural competence involves flexibility—an ability to understand the child or family’s experience from their frame of reference rather than from one’s own [45]. Cultural humility is the life-long commitment to personal reflexivity and the self-critique of one’s culture and enables medical service providers to develop non-authoritarian relationships with their clients [46]. Culturally responsive school psychology has an ethos of cultural reflexivity where cultural flexibility and humility are practised.

- CRT is radical: It challenges dominant and exclusive knowledge systems and highlights the importance of indigenous ways of being [38]. Therefore, CRT is inclusive and can potentially revolutionise school psychology to benefit diverse learners.

- CRT gives prominence to indigenous cultures: Responsive therapists are lifelong learners who commit to learning about their client’s cultures (author, 2020) [47] and seek proactive opportunities to acquire cultural knowledge (Parekh et al., 2014) [42]. They are also mindful of within-group variations and honour how each family culturally identifies [47]. They can locate family indigenous cultural norms, customs, and practices by asking. School psychologists honouring indigenous knowledge can maximise cultural healing practices that are natural to refugee learners.

- CRT is accountable to the needs of stakeholders [41]. Meeting the needs of families as they state them creates an atmosphere of accountability that benefits refugee families [42]. A responsive therapist is accountable because they put their cultural knowledge into practice. As previously stated, migrant children are underrepresented in mental health services [17], and for many refugee children, consultation with a mental health practitioner may be a novel experience; accountability can increase trust and respect in the therapeutic relationship. Rapport, respect, and mutual understanding may increase therapy interest and retention among refugee families.

- CRT is collaborative [47]: Refugee families often present with urgent physical and economic needs that cause them emotional distress. While assisting refugees in acquiring material and financial resources may not be within the scope of practice for psychologists, therapists should not ignore or disregard learners’ material and economic needs. Continuing with psychotherapy with learners who do not have their basic needs met is possibly counterproductive. School psychologists can collaborate with refugee agencies that provide material and financial services to refugee families to assist learners in getting their basic needs fulfilled. Thus, therapists need to establish a strong network of collaboration with agencies that provide various services to refugee families [47].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Sample

2.2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- Refugee children who had experienced open war and were displaced as a result of violent conflict.

- Refugee children participating in family or individual trauma-informed psychological therapy.

- Psychologists and therapists providing family therapy to refugee children.

- Expert discussions on refugee children’s experiences of pre-migration, migration, and post-migration traumatic stressors.

2.2.3. Search Criteria

2.3. Data Analysis

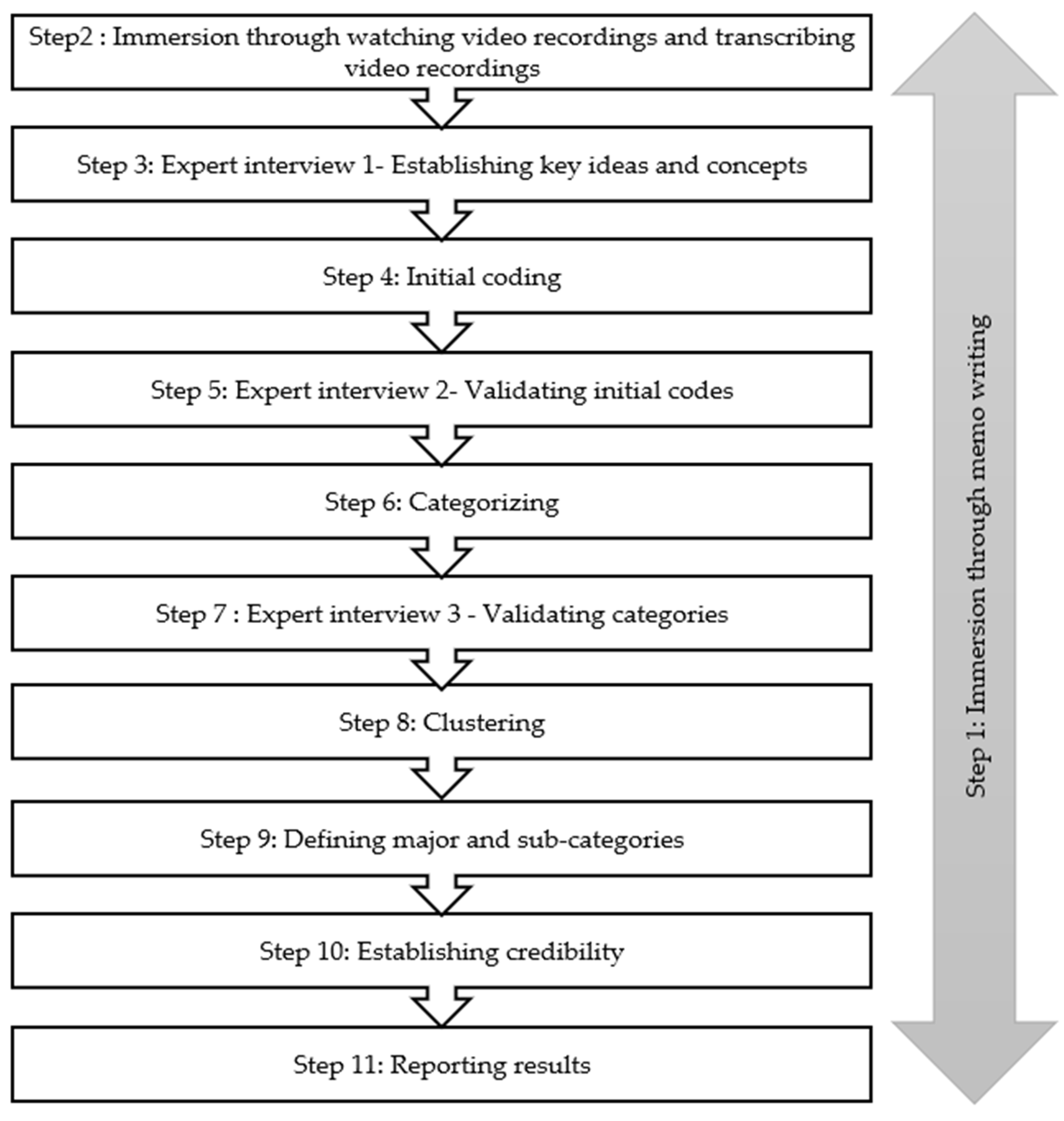

Analysis Procedure

- Immersion through memos. The researcher used memos to conceptualise and theoretically link emerging themes.

- Immersion through watching and transcribing video recordings. The researcher watched the video materials several times to become familiar with the data and then transcribed the video materials into written documents.

- Expert interview 1—Establishing key ideas and concepts. This expert was considered an extension of the literature on psychotherapy with refugee families because the literature on this topic is lacking, and they assisted the researcher in defining key ideas and concepts.

- Initial coding. Initial coding was conducted through word-by-word and line-by-line coding.

- Expert interview 2—Validating initial codes. The second expert validated the emerging initial codes.

- Categorising. Initial codes were compared to each other and then conceptually organised into categories.

- Expert interview 3—Validating categories. The third expert validated emerging categories.

- Clustering. Major and sub-categories were organised into meaningful units to create conceptual clusters.

- Defining major and sub-categories. The definitions of the categories were constructed as an ongoing process from initial coding to clustering. In this step, emerging definitions were solidified.

- Establishing credibility. Three senior researchers ensured the study’s credibility by analysing the audit trail.

- Reporting results. Findings are reported in major categories. Exemplar quotations from the transcripts are given to substantiate the reported categories.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

- Theme 1: Children are not spared from war trauma.

I was terrified. I didn’t know what was happening. I saw everyone running, and I had no idea why. Everyone was screaming. When war broke out in my region, we were taken to a stadium, it was a soccer stadium. I stayed there for about four days. There were so many people and lots of disease and massacring. Then things went bad to the very worst. The weather was awful. It was raining, and blood flowed everywhere. We were swimming in blood; there were so many wounded. That has stayed with me; it won’t go away…. At five, I had no idea what a massacre was. (Ampersand Film & Video Tape Productions, 2005, 00:10:53)

Some children have never known peace. They have faced violence since birth. They move from one refugee camp to another until they arrive in Canada. For these children, the conflict remains within, and it’s still active. (Multimedia Group of Canada, 2000, 00:02:17)

Often, we have this myth or belief that now that they are in the U.S., life is fine. It’s just everyday challenges, but some of the things we have to remember are, first, how the pre-migration experiences impact the post-migration. (American Psychological Association, 2009, 00:00:22.11)

- Theme 2: Children live in perpetual fear and anxiety.

Soldiers scare me when they shoot. When they shoot real bullets, I am scared one of the bullets might hit my brothers or sisters. (Ampersand Film & Video Tape Productions, 00:16:03)

She wakes up in the middle of the night crying. She has nightmares about tanks crushing us. They will raze the house while we’re asleep, crushing us, and no one will know. (Ampersand Film & Video Tape Productions, 2005, 00:06.25)

Ahmed is 21. He lives with his family in Rafah. A year ago, during an incursion by the Israeli army, he was hit in the chest by two bullets fired from a tank turret. He was plunged into a four-month coma but eventually awoke and survived. (Ampersand Film & Video Tape Productions, 2005, 00.02.55)

Among children, post-traumatic stress disorders generally manifest themselves as anxiety attacks, difficulty concentrating, loss of interest in everyday activities, trouble in school, fatigue, insomnia, nightmares, and aggression. Such symptoms can appear months or years after the trauma, the memory of which is triggered by a simple sensory event. (Multimedia Group of Canada, 2000, 00:24:42)

- Theme 3: War-related violence ignites aggressive behaviours in children.

In war situations, violence is constantly reactivated by events, of course. This is particularly important in children. How do they grow up in violence without that violence becoming an integral part of them? (Ampersand Film & Video Tape Productions, 2005, 00:30:24)

All the anger and sadness they were exposed to ends up manifesting itself as destructiveness. The anger they carry inside must not become self-destructive or destructive to others through anti-social behaviour. (Multimedia Group of Canada, 2000, 00:25:56)

The most damaging traumas are those arising from human violence. The psychological repercussions are always more significant in such cases. The capacity to trust others is deeply affected. (Multimedia Group of Canada, 2000, 00:11:33)

4. Discussion

4.1. Considerations for Culturally Responsive School Psychology

4.2. Study limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations High Council for Refugees (UNHCR). Global Appeal Report 2021. 2021. Available online: https://reporting.unhcr.org/globalreport2021 (accessed on 26 December 2023).

- United Nations High Council for Refugees (UNHCR). Global Trends Forced Displacement in 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/global-trends-report-2022 (accessed on 26 December 2023).

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Child Displacement and Refugees. 2022. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-migration-and-displacement/displacement/ (accessed on 31 December 2023).

- Walker, A. Transformative Potential of Culturally Responsive Teaching: Examining Preservice Teachers’ Collaboration Practices Centering Refugee Youth. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Olivo, S.M. Introduction to Special Issue: Culturally Responsive School-Based Mental Health Interventions. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 2017, 21, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Narasiah, L.; Munoz, M.; Rashid, M.; Ryder, A.G.; Guzder, J.; Hassan, G.; Rousseau, C.; Pottie, K. Common Mental Health Problems in Immigrants and Refugees: General Approach in Primary Care. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2011, 183, E959–E967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Rights Watch. World Report 2019: Events of 2018. 2019. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019 (accessed on 31 December 2023).

- Osokina, O.; Silwal, S.; Bohdanova, T.; Hodes, M.; Sourander, A.; Skokauskas, N. Impact of the Russian Invasion on Mental Health Of Adolescents in Ukraine. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 62, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizkalla, N.; Mallat, N.K.; Arafa, R.; Adi, S.; Soudi, L.; Segal, S.P. “Children are not Children Anymore; They are a Lost Generation”: Adverse Physical and Mental Health Consequences on Syrian Refugee Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2020, 17, 8378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bemak, F.; Chung, R.C.Y. Refugee Trauma: Culturally Responsive Counseling Interventions. J. Couns. Dev. 2017, 95, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vossoughi, N.; Jackson, Y.; Gusler, S.; Stone, K. Mental Health Outcomes for Youth Living in Refugee Camps: A Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2018, 19, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, C.; Frost, R.; Sherwood, L.; Shevlin, M.; Hyland, P.; Halpin, R.; Murphy, J.; Silove, D. Post-Migration Factors and Mental Health Outcomes in Asylum-Seeking and Refugee Populations: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2020, 11, 1793567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, L.; Liamputtong, P. Acculturation Stress and Social Support for Young Refugees in Regional Areas. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 77, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiser, M.; Hou, F. Predictors of Positive Mental Health Among Refugees: Results from Canada’s General Social Survey. Transcult. Psychiatry 2017, 54, 675–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, M.; Reed, V.R.; Panther-Brick, C.; Stein, A. Mental Health of Displaced and Refugee Children Resettled in High-Income Countries: Risk and Protective Factors. Lancet 2012, 379, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasser, L.R. Addressing Mental Health Concerns in Refugees and Displaced Populations: Is Enough Being Done? Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2022, 15, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubi, E.; Sjöqvist, H.; Viksten-Assel, K.; Bäärnhielm, S.; Dalman, C.; Hollander, A.-C. Mental health service use among migrant and Swedish-born children and youth: A register-based cohort study of 472,129 individuals in Stockholm. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filler, T.; Georgiades, K.; Khanlou, N.; Wahoush, O. Understanding Mental Health and Identity from Syrian Refugee Adolescents’ Perspectives. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 764–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Haintz, G.L. Influence of the Social Determinants of Health on Access to Healthcare Services among Refugees in Australia. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2018, 24, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCleary, J.S. The Impact of Resettlement on Karen Refugee Family Relationships: A Qualitative Exploration. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2017, 22, 1464–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, N.; Hameed, S.; Acarturk, C.; Deniz, G.; Sheikhani, A.; Volkan, S.; Örücü, A.; Pivato, I.; Akıncı, İ.; Patterson, A.; et al. Prevalence of Common Mental Disorders Among Syrian Refugee Children and Adolescents in Sultanbeyli District, Istanbul: Results of a Population-Based Survey. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodes, M. Editorial Perspective: Mental Health of Young Asylum Seekers and Refugees in the Context of COVID-19. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 190–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauhanen, L.; Wan Mohd Yunus, W.M.A.; Lempinen, L.; Peltonen, K.; Gyllenberg, D.; Mishina, K.; Gilbert, S.; Bastola, K.; Brown, J.S.; Sourander, A. A Systematic Review of the Mental Health Changes of Children and Young People Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 32, 995–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Qi, H.; Liu, R.; Feng, Y.; Li, W.; Xiang, M.; Cheung, T.; Jackson, T.; Wang, G.; Xiang, Y.T. Depression, Anxiety and Associated Factors Among Chinese Adolescents During The COVID-19 Outbreak: A Comparison of Two Cross-Sectional Studies. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Kaman, A.; Erhart, M.; Devine, J.; Schlack, R.; Otto, C. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Quality of Life and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents in Germany. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 31, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedzwiedz, C.L.; Green, M.J.; Benzeval, M.; Campbell, D.; Craig, P.; Demou, E.; Leyland, A.; Pearce, A.; Thomson, R.; Whitley, E.; et al. Mental Health and Health Behaviours Before and During the Initial Phase of the COVID-19 Lockdown: Longitudinal Analyses of the UK Household Longitudinal Study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2021, 75, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackmore, R.; Gray, K.M.; Boyle, J.A.; Fazel, M.; Ranasinha, S.; Fitzgerald, G.; Misso, M.; Gibson-Helm, M. Systematic Review, and Meta-Analysis: The Prevalence of Mental Illness in Child and Adolescent Refugees and Asylum Seekers. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, L.R.F.; Büter, K.P.; Rosner, R.; Unterhitzenberger, J. Mental Health and Associated Stress Factors in Accompanied and Unaccompanied Refugee Minors Resettled in Germany: A Cross-Sectional Study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2019, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasıroğlu, S.; Çeri, V.; Erkorkmaz, Ü.; Semerci, B. Determinants of Psychiatric Disorders in Children Refugees in Turkey’s Yazidi Refugee Camp. Psychiatry Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 28, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slone, M.; Mann, S. Effects of War, Terrorism and Armed Conflict on Young Children: A Systematic Review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2016, 47, 950–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayuphan, J.; Sangthong, R.; Hayeevani, N.; Assanangkornchai, S.; McNeil, E. Mental Health Problems from Direct Vs Indirect Exposure to Violent Events Among Children Born and Growing Up in a Conflict Zone of Southern Thailand. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020, 55, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geltman, P.L.; Augustyn, M.; Barnett, E.D.; Klass, P.E.; Groves, B.M. War Trauma Experience and Behavioral Screening of Bosnian Refugee Children Resettled in Massachusetts. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2002, 21, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, R. Child Refugees, Trauma and Education: Interactionist Considerations on Social and Emotional Needs and Development. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2009, 25, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowling, M.M.; Anderson, J.R. The Effectiveness of Therapeutic Interventions on Psychological Distress in Refugee Children: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 79, 1857–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipalo, E. Is Trauma Focused-Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) Effective in Reducing Trauma Symptoms among Traumatized Refugee Children? A Systematic Review. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2021, 14, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, K.; Spencer, A. A Full Systematic Review on the Effects of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Mental Health Symptoms in Child Refugees. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2021, 23, 624–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, J.J.; Gale, J.E.; Bacigalupe, G. The Discourse of Race and Culture in Family Therapy Supervision: A Conversation Analysis. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2001, 23, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancis, J.R. Culturally Responsive Practice. In Culturally Responsive Interventions: Innovative Approaches to Working with Diverse Populations; Ancis, J.R., Ed.; Brunner-Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 2–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, D.E.; Kredlow, M.A.; Bui, E.; Pollack, M.H.; Hofmann, S.G. Treatment Change of Somatic Symptoms and Cultural Syndromes Among Cambodian Refugees with PTSD. Depress. Anxiety 2012, 29, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrow, Y.; Pajak, R.; Specker, P.; Nickerson, A. Perceptions of mental health and perceived barriers to mental health help-seeking amongst refugees: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 75, 101812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seponski, D.M.; Lewis, D.C.; Megginson, M.C. A Responsive Evaluation of Mental Health Treatment in Cambodia: Intentionally Addressing Poverty to Increase Cultural Responsiveness in Therapy. Glob. Public Health 2014, 9, 1211–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, H.B.; Murray, K.; Barrett, C. Understanding the Mental Health of Refugees: Trauma, Stress, and the Cultural Context. In The Massachusetts General Hospital Textbook on Diversity and Cultural Sensitivity in Mental Health; Parekh, R., Ed.; Human Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 165–187. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar, A.; De Shazer, S. Solution-focused Therapy: Toward the Identification of Therapeutic Tasks. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 1987, 13, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Shazer, S. Clues: Investigating Solutions in Brief Therapy; W.W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Clauss-Ehlers, C.S.; Serpell, Z.N.; Weist, M.D. Introduction: Making the Case for Culturally Responsive School Mental Health. In Handbook of Culturally Responsive School Mental Health: Advancing Research, Training, Practice, and Policy; Clauss-Ehlers, C.S., Serpell, Z.N., Weist, M.D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Tervalon, M.; Murray-Garcia, J. Cultural Humility Versus Cultural Competence: A Critical Distinction in Defining Physician Training Outcomes in Multicultural Education. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 1998, 9, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somo, C.M. Trauma-Informed Family Therapy: Considerations for The Systemic Treatment of Trauma in Refugee Communities. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA.

- Roller, M.R. A Quality Approach to Qualitative Content Analysis: Similarities and Differences Compared to Other Qualitative Methods. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2019, 20, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Widermuth, B.M. Qualitative Analysis of Content. In Applications of Social Research Methods to Questions in Information and Library Science, 2nd ed.; Wildermuth, B.M., Ed.; Libraries Unlimited: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 159–176. [Google Scholar]

- Ampersand Film and Video Tape Productions. After the Outrage: Violence, Trauma, and Recovery, Ampersand Film & Video Tape Productions & Films Media Group: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2005; ISBN 978-1-62290-222-4.

- Multimedia Group of Canada. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: When the Memories Won’t Go Away; Multimedia Group of Canada: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2000; ISBN 978142137145-0. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Series V-Multicultural Counseling: Working with Immigrants; APA Videos: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-4338-0369-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ochberg, F.; Panos, A. Living with PTSD: Lessons for Partners, Friends and Supporters; Psychotherapy.net/videos: Radnor, PA, USA, 2012; ISBN 1-60124-300-6. [Google Scholar]

- VoicesAcademy. Interpreting for Refugees in Social Service Encounters. 2014. Available online: https://voicesacademy.com/interpreting-for-refugees-in-social-service-encounters/ (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- Slutskaya, N.; Game, A.M.; Simpson, R.C. Better Together: Examining the Role of Collaborative Ethnographic Documentary in Organizational Research. Organ. Res. Methods 2018, 21, 341–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skilling, K.; Stylianides, G.J. Using Vignettes in Educational Research: A Framework for Vignette Construction. Int. J. Res. Method. Educ. 2020, 43, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.G. The Ethics of Internet Research. Online J. Nurs. Inform. 2012, 16, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Morina, N.; Nickerson, A. (Eds.) Mental Health of Refugee and Conflict-Affected Populations: Theory, Research and Clinical Practice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ratts, M.J. Multiculturalism, and Social Justice: Two Sides of the Same Coin. J. Multicult. Couns. Dev. 2011, 39, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Video Reference | Video Information | Helping Professional’s Biography (at the Time of Recording) |

|---|---|---|

| Ampersand Film & Video Tape Productions, & Films Media Group [50]. | Documentary film 56 min recording Retrieved from Films on Demand, a part of the University of Georgia video archives. | Dr. Christian Lachal is a psychoanalyst and ethnopsychiatrist who, at the time of filming the documentary, was the head of the mental health programme at Medecins Sans Frontieres. Dr. Cecile Rousseau is a psychologist who has worked with refugee families from Asia and has extensive experience working with refugee children and their families. |

| Multimedia Group of Canada [51]. | Documentary film 53 min recording Retrieved from the University of Georgia library video archives. | Lieutenant Commander Sylvain Landry is a war/veteran’s psychiatrist and the Operational Trauma and Stress Support Center director. Cécile Rousseau is a psychiatrist working with refugee children at a children’s hospital. Déogratias Bagilishya is a psychologist working with refugee children at a children’s hospital. Louise Gaston is a psychologist and the director of Traumatys. Danielle Dion is an art therapist working with survivors of sexual abuse. Danielle Droplet is a social worker working with survivors of domestic violence. |

| American Psychological Association [52]. | Instructional video 100 min recording Sourced from the APA video database. | Dr. Rita Chi-Ying Chung is a licensed marriage and family therapist and a professor in counselling and development at the College of Education and Human Development at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia. |

| Frank Ochberg & Angie Panos [53]. | Instructional video 18 min of recording Retrieved from the University of Georgia Library. | Dr. Angelea Panos holds a Ph.D. in clinical psychology. She is a licensed marriage and family therapist and a licensed clinical social worker. Dr. Frank Ochberg is a psychiatrist, the former Associate Director of the National Institute of Mental Health, and a member of the team that wrote the medical definition of Traumatic Stress Disorder. |

| VoicesAcademy [54]. | Educational video 68 min recording Retrieved from Video file https://voicesacademy.com/interpreting-for-refugees-in-social-service-encounters/ (accessed on 16 December 2023). | Ms. Kathleen To is a licensed clinical social worker with extensive refugee resettlement programme experience. |

| CRT Principles | CRT Integration in Therapy |

|---|---|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Somo, C.M. The Mental Well-Being and Inclusion of Refugee Children: Considerations for Culturally Responsive Trauma-Informed Therapy for School Psychologists. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 249. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030249

Somo CM. The Mental Well-Being and Inclusion of Refugee Children: Considerations for Culturally Responsive Trauma-Informed Therapy for School Psychologists. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(3):249. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030249

Chicago/Turabian StyleSomo, Charity Mokgaetji. 2024. "The Mental Well-Being and Inclusion of Refugee Children: Considerations for Culturally Responsive Trauma-Informed Therapy for School Psychologists" Education Sciences 14, no. 3: 249. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030249

APA StyleSomo, C. M. (2024). The Mental Well-Being and Inclusion of Refugee Children: Considerations for Culturally Responsive Trauma-Informed Therapy for School Psychologists. Education Sciences, 14(3), 249. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030249