3.2.1. Collaboration

The teachers at the school under study now meet every two weeks to manage the learning process of all the students in a given year in interdisciplinary teams, whereby the core curriculum management unit is no longer the subject departments but the educational teams, as a means of promoting more interdisciplinary work. The results of the questionnaires administered to the teachers (

n = 54) illustrate that their perceptions of the dynamics of the work they do are very positive, as shown in

Table 4.

Observations, interviews, focus groups and the analysis of meeting memos provided us with a better understanding of how these collaborative dynamics are interknit within these teams.

As far as collaborative curriculum management is concerned, although the educational teams are interdisciplinary, it is clear that the work continues to be carried out in an essentially disciplinary dynamic, with only occasional moments of interdisciplinary planning, as confirmed by one of the educational team coordinators (C):

“Everyone works on a given document to the best of their ability, but it’s still done within the scope of their subject with regard to their pupils.”

(C2)

In the area of collaborative student management, each teacher felt responsible for all the students’ learning processes, as one teacher (T) said, and were free to form flexible groups of students, but only in two of the educational teams, the seventh and ninth grades, due to work distribution constraints, as the principal (P) explained. Moreover, they felt that this form of management placed an excessive focus on the students with the most difficulties.

“Prior to working in the educational team, I was responsible for the classes I taught. Now, I feel responsible for all the fifth-graders, which is the educational team I belong to…”

(T1)

“First of all, it’s a question of drawing up timetables. It’s very difficult to draw up timetables that are well-balanced, both for the class and the students, and for the teacher. That’s why we can only work with two school years.”

(P)

Regarding the production of documents, various documents were drawn up together, including plans, recovery plans, meeting memos and curricular specifications, but they had little time to collaborate on teaching materials.

“With regard to the production of teaching materials, I think this part was missing.”

(T3)

Therefore, we have seen an investment in plans, in a more bureaucratic approach, but we have also noticed a lack of time for planning teaching activities and the production of didactic materials in a joint manner, which may have hindered the collaborative management of the curriculum, as well as the implementation of interdisciplinary projects with the use of more active methodologies.

The teachers in the educational teams also had the opportunity to make joint decisions regarding the group of students comprising Class Plus, the transversal strategies for remedial students—the students to be given educational support, tutoring or mentoring. However, their efforts to increase flexibility were limited by their impotence to adjust timetables or curricula during the teaching cycle. In addition, they were still very much tied to the annual planning of subjects and essential learning, which is assessed in external tests.

“However, the team should have more autonomy to manage their work, to draw up timetables, curricula and more flexible groups of pupils, which are still very restricted and are a major constraint to effective curricular flexibility.”

(C2)

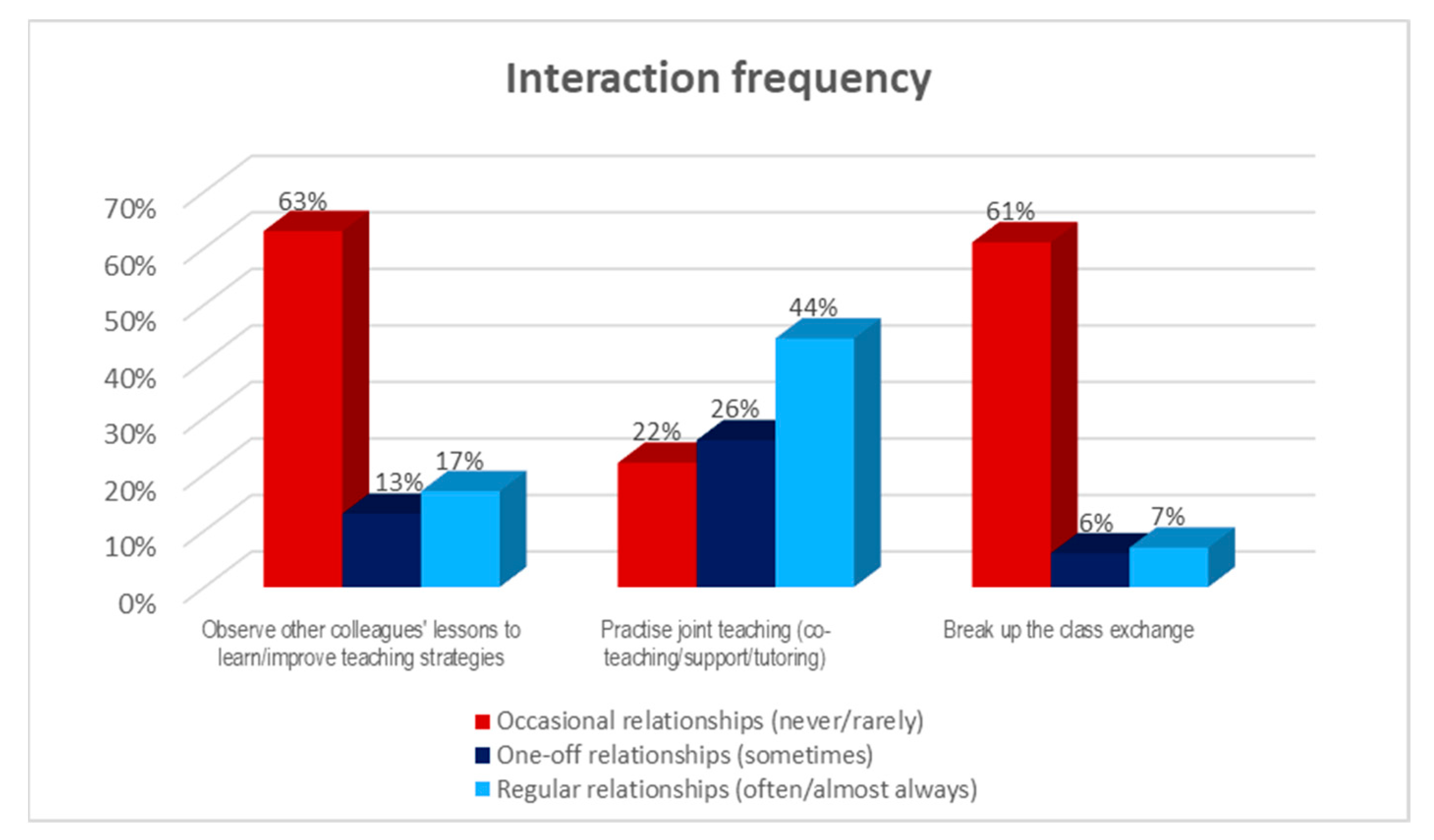

With regard to sitting in on colleagues’ lessons, as we have seen previously, this is not a common practice at the school. However, a certain amount of co-teaching does exist, which has been viewed in a very positive light, as this has enabled teachers to learn new strategies and new ways of dealing with students, more individualized support for students, enhanced management of time and the classroom environment, as well as the exchange of roles between assistant teachers and lead teachers.

“The assistant teacher, who is closer to the students, encourages them to participate orally and to ask questions, which is very important in the students’ learning process, in addition, of course, to the class being managed differently. We have another teacher in the classroom.”

(T1)

“Of course, if we’re there, we’re learning, aren’t we? As T5 said earlier, it’s just another class, […] we’re learning our colleagues’ strategies, we sometimes don’t even think about them, do we? It’s just like that. And the way we react to certain problems…”

(T2)

The collaborative dynamics between the teachers were also characterized by an evaluation of the functioning of Class Plus, of indiscipline in the different classes and by an analysis of formative assessment: diagnosis of weaknesses and analysis of student progress.

“As for assessment, there is constant reflection on the data arising from formative assessment. We try to understand what is behind the failure of some students…but there is always a tendency to blame the lack of work and autonomy of the students, the lack of support from families and we don’t address teaching practices head-on.”

(C2)

We also realized that the analysis of data was very much focused on the students with the most difficulties and their attitude, and there was rarely any reflection on the teaching practices that might be promoting or hindering these students’ learning. In fact, the remediation strategies, both at a disciplinary level and in a more transdisciplinary way, aimed at changing the student’s attitude without directly implying a review or reformulation of the teaching practices used in the classroom.

As for the sharing of knowledge and practices, although we have seen information on all the students shared in a given year, we still notice certain difficulties on the part of some teachers in sharing good practices or knowledge acquired in other training experiences.

“I think the open sharing of good practices is starting to happen, but it’s not exactly widespread yet.”

(C1)

“Others do, but they always focus on the student’s behavior and not on the teacher’s strategies. It’s difficult, you know…”

(C2)

This brief description of the collaborative dynamics of the educational teams reveals that most of the time dedicated to team meetings was spent discussing official issues with the other teachers, namely the following: compliance with the programs, the planning and assessment tools to be used and reflections on the formative assessment of students. However, teachers rarely shared their personal practices—their way of approaching difficult content—by drawing on their experience to exchange knowledge with colleagues. Furthermore, the reflections carried out rarely invaded the privacy of the classroom and each other’s practices. We also saw constant reflection on the data arising from formative assessments, striving to understand what is behind the failure of some students; however, this reflection was marked by a tendency to blame the failure on the students’ lack of work and autonomy, and on a lack of support from their families.

Hence, there seem to be a number of dynamics in educational teams that are favoring collaboration between teachers, with a gradual increase in interdependence and collectivity. However, it seems that teachers’ learning may be limited in these teams due to a lack of critical analysis of the problems of practice, as Wedder-Weiss et al. [

55] and Chua et al. [

21] also concluded. Indeed, learning in PLCs involves deep reflection on what is being done, on why and how it may be contributing to the problems faced by children in their learning and checking whether the actions reviewed make a positive difference to the students. Therefore, we conclude that in order to create individual and collective knowledge, these educational teams need to reinforce the extent of their tacit knowledge based on observation, but fundamentally based on a reflective dialogue that enables them to understand what has been observed [

4].

3.2.2. Collegiality

According to a preliminary analysis based on the questionnaire survey administered to the teachers (

n = 54), they seem to believe there is a working culture in the educational teams that encourages solidarity, cooperation, mutual assistance and mutual respect among its members, as illustrated in

Table 5.

However, a more in-depth analysis, based on the observations made at the meetings of the educational teams and the interviews and focus groups, led us to realize that there is a core group of teachers in the teams that support, encourage and help each other; however, we noticed the existence of a fringe of teachers, more specifically those that experience difficulties working with more complex content or dealing with classes, who felt embarrassed to share their weaknesses and expose their vulnerability.

“This mutual support does and doesn’t exist, unfortunately. Unfortunately, I think it exists among those who don’t need it as much and it doesn’t exist among certain people who would probably benefit from it enormously.”

(C1)

Therefore, it seems that the teachers showed confidence in their team generally speaking, but this confidence was not tested by confronting difficulties or less consistent and effective practices, or by openly sharing everything that happened in the classroom. Not all the teachers felt confident enough to acknowledge their weaknesses and preferred not to reveal them.

“The working environment is positive, because everyone is very respectful of each other’s glass enclosure, no-one encroaches on each other’s space, and nothing is questioned...In this sense, everything works well, there seems to be trust. […] When there are problems, teachers in difficulty still don’t have the courage to open up to their colleagues. You have to remember that teacher evaluation requires this…you have to hide your weaknesses and not open up too much. In this sense, it seems to me that there is no consistent, solid trust.”

(C2)

We found that most teams enjoyed a good working environment; however, the standoffish attitude of the teachers that were unwilling to engage in collaborative dynamics sometimes led to them failing to show mutual respect for their colleagues, striking up parallel conversations and permanently disagreeing with every idea put forward.

“While this debate was going on, the three teachers […] continued with their parallel conversations, paying very little attention to what was being discussed at the meeting.”

(Field diary note)

As a result, it seemed to us that not all the members of the team were on the same page when it came to meeting their common goals. There is a core group of teachers who have provided the work carried out with cohesion and consistency, but there are still teachers marked by a professional culture of individualism that end up undermining the team’s professional cohesion and, consequently, the work of co-creation.

“[…M]isaligned teachers still exist, and come to meetings because they’ve been invited in advance by the principal, behave like employees, only attend so they’re not registered as absent and who add little to the conclusions drawn or to the decisions being made.”

(Field diary note)

Along the lines of Ismail et al. [

6] and Zhang et al. [

60], we can see that this lack of individual and collegial commitment on the part of some teachers, their lack of understanding of the concept of PLCs and their lack of a collaborative professional culture may be hindering the effective functioning of the teams, insofar as a sense of belonging and professional and social cohesion among teachers is fundamental to enabling them to hold open discussions in order to improve and strengthen pedagogical practices in the classroom [

61]. Moreover, teacher commitment and motivation are two of the determining variables of educational change [

62].

3.2.3. Leadership

The creation of the educational teams gave rise to a new middle management structure, the year coordination, carried out by the educational team coordinators. We will focus our attention on the actions of these middle leaders in order to understand the effect they have on promoting collaborative work among teachers and on their professional development. As illustrated in

Table 6, the teachers’ perceptions of the performance of the educational team coordinators are very positive.

To analyze and interpret this data, we based our research on the dimensions of effective leadership according to Bolivar [

42]: setting goals and expectations; ensuring an appropriate context and the necessary support (providing intellectual stimulation); promoting and participating in teachers’ professional development, evaluating them through regular classroom visits and providing feedback.

According to the perception of the majority of the teachers, in accordance with the data in

Table 6, it seems that the educational team coordinators ensured a suitable scenario for collaboration and the necessary support for the teachers, as they regularly created and clarified common work goals, helped to clarify doubts and shared relevant information. They also tried to stimulate the teachers intellectually, taking their opinions and suggestions into account, promoting moments of reflection and collective decision-making, integrating, and valuing the group’s different standpoints and perspectives.

Observing educational team meetings and interviewing the coordinators and teachers enabled us to see that the educational team coordinators were concerned with promoting a set of collaborative dynamics based on the definition of common goals to be achieved and common strategies to achieve them.

“Yes, what was defined at the beginning of the educational team’s work was to accompany and make sure that all the students concluded the year successfully.”

(C2)

“Recovering lost learning, everyone on the road to the educational success of the students, of every student, right from the start of the year, that was the goal.”

(T2)

Furthermore, we noticed that the coordinators were keen to promote collaboration between the members of the team, striving to involve everyone in the dialogue, sharing the structure of the memo on Drive beforehand, in order to guide the preparation of colleagues and to promote their participation, as well as sharing a set of relevant data to promote reflection and monitoring of the students’ results and learning.

“As the person in charge, I take stock of the results in good time and present them to the team, and we all discuss them together.”

(C1)

However, the discussions focused largely on the most unsuccessful students, and we did not see any concern on the part of the coordinators in triggering an analysis—a confrontation of the teaching practices that could be at the root of this failure, which was usually attributed to external causes.

“Over the course of all the educational team meetings we observed, difficulties in getting certain students to develop were undoubtedly shared, but the focus was always on the lack of family support, their lack of autonomy, their lack of organization, their lack of interest. At no time did the discussions lead to an analysis of the classroom practices that might be the cause of the student’s lack of interest.”

(Field diary note)

We also found that not only did the educational team coordinators fail to address the practices implemented in the classroom during the meetings, but they also did not supervise these practices either, as it is not their job to observe their colleagues’ lessons. Thus, as in Leithwood’s [

63] findings on the performance of department coordinators, it seems that the educational team coordinators also find the activity of evaluating and reviewing the work of their team’s teachers embarrassing, avoiding addressing some of the practices implemented, as well as difficult questions, and concentrating their efforts on verifying compliance with previously defined plans. This approach may also be limiting teachers’ deep learning, which, on the contrary, involves the desire and courage to reflect and examine in order to improve practices. However, egalitarian, autonomous standards, high levels of work-related pressure on teachers and the risk of dropping out or resistance make leadership for deep learning highly complex [

64].

3.2.4. Professional Value

However, this fragile dialogical reflection, a lack of investigative capacity, a certain lack of trust and professional cohesion and a tenuous role for middle leadership in promoting a change in teachers’ mentality may be acting as obstacles to the promotion of teachers’ professional value, or in other words, to changing the way in which they view teaching, their positive behavior and the way they teach.

Indeed, the mentality of these teachers still seems very balkanized, focused on their specific knowledge of each discipline and not very open to interdisciplinarity and collaboration with colleagues from other disciplines.

“Now, in order to ensure students are better prepared, we need to change the way teachers think, stop them from thinking in terms of their area, from thinking exclusively about their subject area, their classroom and their class, and to start thinking about a year of schooling, thinking in a transdisciplinary manner and in such a way that the contents of their subject area make sense in other subject areas.”

(P)

Moreover, a persistent mentality of insecurity exists, which may explain a certain lack of confidence and a fear of experimenting, rehearsing, and failing—essential processes in individual and collective learning.

“You have to get to grips with it, you have to try it, you have to fail, you have to live it all…so that you can grow in the profession.”

(C1)

Teachers are still marked by an individualistic mentality, blocked by the idea that the teacher is a transmitter of knowledge, who knows what they can and should do in their classroom to resolve their students’ problems, preferring to stay in their comfort zone and manage their personal affairs. Indeed, a closed and passive mentality persists, with little receptiveness to sharing weaknesses, confronting practices and criticizing colleagues. This perspective leads teachers to opt for a passive role, not actively engaging in the work dynamics and waiting for orders from leaders on how to proceed, from a continuously and highly bureaucratic perspective.

“They still think that being a teacher means preparing lessons, teaching subjects, filling in tables and little else…Collaborative work and joint thinking are not part of their job description, not least because they are capable of resolving the problems that arise in their classrooms.”

(C2)

We also see a mentality marked by a lack of ethical and moral commitment: it seems that everyone is responsible, but no one takes responsibility for failures.

“[…T]here’s a tendency to blame the lack of work and autonomy on the students, the lack of support from families, and the teaching practices aren’t tackled head-on. Everyone is in their own little bubble and it’s very difficult to approach them in this way…”

(C2)

Therefore, it seems to us that teachers’ deep learning is being blocked by the persistence of a fossilized, closed, individualistic, balkanized, conformist mentality, marked by insecurity and mistrust. However, according to Lund [

23], changing teachers’ mindsets and practices implies that their habitual thoughts and actions are examined and called into question, which only happens, on the one hand, when every member opens up their mind and is willing to be criticized [

5] in a logic of understanding, empowerment and support. On the other hand, this reflection cannot and should not be exclusively technical or instrumental, i.e., focused, as was the case in the educational teams studied, on the students’ results. On the contrary, it must be much broader, including moral, emotional and political aspects of teaching, and much deeper, touching on the beliefs and representations teachers have of themselves and of teaching. Without this critical and in-depth character, reflection runs the risk of being a mere procedure, a method or a confrontational strategy that perpetuates the status quo, and which can contribute to the devaluation of a teacher’s professionalism [

65].

In this way, this reserved and tendentiously closed mentality typical of some teachers can explain the negative and passive attitude of some towards participating in educational teams, their lack of ethical and moral commitment, which is one of the major inhibitors of collaborative PLC practices [

60,

66], and the affirmation of a teacher’s professionalism [

62].

3.2.5. Focus on Student Learning

The basic principle of a PLC is to improve student learning by improving teaching practices. It therefore seems relevant to us to demonstrate how belonging to an educational team has affected the pedagogical activities themselves. To do this, we will base ourselves not only on the three basic functions of the school, instruction, socialization and stimulation [

67], reflected in the four pillars of education, learning to know, learning to do, learning to live together and learning to be [

68], but also in the data resulting from the students’ evaluation of the quality of teaching, the classroom environment and the well-being and support of the teachers.

As far as instruction is concerned, based on lesson observations (

n = 12), we recorded the most frequently implemented practices and found that, as illustrated in

Table 7, the most frequent practices continue to be the methodologies of explanation and training [

69], operationalized through the presentation of content in interaction with the students and/or using PowerPoint (version 2401) and interactive platforms; the resolution of exercises using worksheets and activity books; individual and pair work. Our observations did not provide us with the opportunity to observe more active and exploratory methodologies such as project work, research work, experimental activities or the flipped classroom technique.

This data was confirmed by the students (S) in the focused discussion group. From their interventions, we can see that the methodologies of participation, production and experimentation are to their liking, as they consider them to be more motivating, more attention-grabbing and to allow for a better understanding of the content, but they have rarely been implemented by teachers.

“I liked the (experimental) classes. It was much more interesting…than sitting there for two hours listening to a teacher, not wishing to be disrespectful. I think there should be more classes like this over the year, because students are more interested in that than sitting there listening and nothing is happening.”

(S1)

Moreover, they also revealed that they enjoyed working in groups, but as there is still no culture of group work at the school, they sometimes confessed that they did not feel prepared to do so consistently and effectively.

“[…] We work more individually, but I think that, above all, we need to feel comfortable in the group we’re in and...to see that the whole group is working towards the same goal…If I feel comfortable, I’ll work in the group, but if I don’t, then I prefer to work individually.”

(S4)

Regarding the use of new technologies, we found that this was a regular practice on the part of both teachers and students, but although it served as an aid to pedagogical practices, it did not revolutionize them, or in other words it remained essentially at the service of the pedagogies of explanation and training.

“In addition to teachers using their platform to register students as absent, who often don’t attend, they use other platforms, such as Kahoot, to supposedly help students understand the subject in a practical way with online exercises.”

(S3)

We therefore conclude that, despite the use of new technologies and some very specific practices of exploration and research pedagogy, there is a weakness in the implementation of student-centered pedagogical approaches geared to promoting active learning and decision-making—with teaching based on specific problems and cases—and capable of promoting critical thinking, which is necessary to face the challenges of the future [

70].

Regarding assessment practices, the students confirmed that concerns have already arisen with regard to assessing different types of essential and transversal learning, using a variety of assessment techniques and instruments, as well as assessing not only the product, but also the process.

“I think it’s important for us to do this kind of work, because I don’t think tests alone will determine our grade, but what we do, what we work on over the year. I think these small assignments are important, above all, for us to improve our grade if we don’t get a good grade in the test or if the test went badly. In fact, I think it’s also a way for us to broaden our knowledge.”

(S4)

Regarding the feedback provided by the teacher, which is an indispensable tool if assessment is to be fully integrated into the learning process [

71], we found that although students regard understanding what they need to do to improve as important, thus providing an incentive for their progress, this is not a common practice at school, either. Oral feedback is more common, while written feedback is almost never given by teachers.

“Yes, I agree, and I think this conversation is important, because students sometimes become lost and don’t know what to do to improve, and this helps them to take a step forward.”

(S2)

“Most teachers just write down the grade (on written work) and don’t put anything in writing, so we don’t…We often don’t understand what we did wrong, or what we should try to innovate and improve.”

(S3)

This systematic lack of the use of feedback may be hindering assessment that serves every student’s learning, focusing on the learning process and understanding successes and failures [

72].

Moving on to the functions of socialization and stimulation, the questionnaire survey administered to the students (

n = 75) shows that the total score for each of these basic school functions, in their perception, is positive, as illustrated in

Table 8.

We also found through the focus group that these functions of socialization and stimulation have been leveraged by Class Plus, which, according to the students, has been the best innovative initiative at the school in recent years.

“I also agree. In my opinion, I believe that Class Plus was one of the best things that happened during the school year.”

(S8)

According to the eight students who took part in the focus group, this temporary and more homogeneous group of students led to an improvement in their sense of belonging, greater identification with their colleagues in the group and, consequently, greater well-being, a better working environment and a greater willingness to participate, collaborate and learn.

“[…] I think it helped create a good atmosphere, to ensure students are at the same level, which makes us look at each other without thinking that someone is at a different level than others, we’re all, as I say, in the same boat. And I think all this has led to a good atmosphere, to everyone having a good experience and improving their skills and grades.”

(S4)

We note that stimulation for learning was also promoted by the existence of Class Plus, where the homogeneity of the group made it easier for the teachers to adapt the instruction to their learning profile, which was also reflected in a greater predisposition for learning and, consequently, an improvement in learning, according to the students and to the teachers.

“I think it was a time when we were able to improve, perhaps even our grades, but above all we were able to improve our skills, especially in languages.”

(S4)

“[…] because we had more support, and we were able to understand the subject better and respond to the things we were asked correctly. Hence, we gained more confidence.”

(S7)

“[…] and the students with difficulties, and this happened in my class last year, which was a very good class, but which had two or three students with difficulties who were afraid to participate, because their classmates were so good that they were afraid of saying something silly, while in Class Plus they were with students with the same profile, the same level, and they realized that, after all, they weren’t the only ones and they started to enjoy participating and lost their fear, which was very, very positive.”

(T3)

“Of course, of course it will improve students’ learning. Yes, it’s a long-term project.”

(T2)

Therefore, it seems to us that a gradual shift is taking place from a paradigm of instruction and transmission, in which the act of educating appears as a formatting operation to a paradigm of learning, where students are seen as the center of educational activity, in which the dimensions of affection and help take on major importance. However, we are still a long way from the communication paradigm, where the focus is on students’ interaction with a given wealth of information, which is culturally valid and considered necessary for life in today’s societies [

73]. This slow change in practices is also proof that we are still facing emerging modes of collective professional practice at the level of educational teams, which need to be reinforced and made more consistent to enable teachers to develop deep learning, which happens in more advanced PLCs in which teachers have already adopted teaching methods that allow students to deal with their learning in an active and cooperative manner [

8].