Abstract

Elective home education is a significant aspect of the UK educational system, yet dedicated research on this topic is limited. This study, employing Appreciative Inquiry, explored the best practices perceived by 90 UK home-educating parents. It uncovered diverse strategies, emphasising the importance of resources such as technology, curricula, and collaborative efforts within home education co-operatives. Parents stressed the value of flexible learning environments and strong family commitment, envisioning a future with an enhanced home learning atmosphere and government and school support. They recommended concrete guidance for prospective home-educating parents, focusing on comprehensive child development. Ultimately, families aspired to shape a future for home education that prioritises enriched learning environments, broader societal recognition, and practical support for those embarking on the home education journey. The study’s findings have implications for children’s development, facilitating collaboration between homes and schools, as well as partnerships between families and educators.

1. Introduction

Elective home education has emerged as a prominent component of the UK’s educational landscape. Over the last two decades, home education has experienced remarkable growth in the country [1,2,3]. Some studies have also shown that even before the pandemic struck, there was an increasing number of parents choosing to educate their children at home in the UK [1,2,4].

Today, home-educated students constitute a substantial minority in the country. The post-pandemic 2021 survey conducted by the Association of Directors of Children’s Services (2021) [1] showed that in England alone, approximately 115,542 children and young people had been home educated at some point during the 2020/2021 academic year. In 2023, it was estimated that between 125,000 and 180,000 children were homeschooled across the four nations in the UK [5]. This constitutes approximately 1.38% to 1.98% of the 9,073,832 pupils attending schools in the country during the same academic year [6].

At present, as per section 7 of the 1996 Education Act in the UK, parents are obligated to ensure that their school-aged child receives “efficient full-time education… either by regular attendance at school or otherwise” [7]. Consequently, parents are permitted to choose to educate their children themselves. Therefore, just like home schoolers in other countries, UK families choose to educate their children at home for a diverse range of reasons [8,9,10,11], seek support from various sources [12], and explore multiple routes to higher education and career paths [13]. However, studies dedicated to this area of research are scarce, and there is a notable lack of studies describing how families engaged in home education in the UK facilitate their children’s learning. For example, many studies were conducted in the UK and much of the current research has been limited to parental motivations to home education, benefits of home educating, and how to start and sustain a home-education cooperative (co-op, i.e., collaborative groups of families working together toward shared goals, encompassing academics, social activities, arts, crafts, service work, and projects).

Furthermore, very few studies exist to inform UK parents on how to select a home-education model and identify various resources to best support their children. There is also a gap in the literature with regard to how home-educating parents utilise different resources and strategies to best equip their children for academic and social success and other areas of development. Against this backdrop, this research used a strength-based, solution-focused approach, the Appreciative Inquiry methodology, to look at what home-educating parents perceive to be best practices in their work with children. The study was conducted online through a questionnaire and follow-up face-to-face focus group interviews to gather qualitative data.

At this juncture, it may be helpful to provide a brief explanation of the key terms used in this study. The term “home education” refers to the practice of educating children in a learning environment led by parents/guardians rather than in a public or private school institution. In essence, parents/guardians take on the primary responsibility for their children’s education during traditional school hours, and this form of education is not necessarily confined to the home. While the term “home schooling” is widely employed in many other countries, as evidenced in the literature, for the purpose of this paper, the term “home education” is used interchangeably with “home schooling”.

2. Background

Reasons for home education vary as do attitudes within the home-educating population. Many parents choose to educate their children at home for pedagogical or ideological reasons, such as to provide a religiously oriented education (e.g., [3,14,15,16]). Others opt to remove their children from schools due to issues such as bullying, school refusal, and general dissatisfaction with school values and demands of learners ([2,11]. For example, Jolly and colleagues’ study found that most of the parents they observed implemented home education only after multiple failures to find a public school that they were satisfied with [17]. Some home-educating parents decided to opt for home education because their children who had additional learning needs were not able to fit into the mainstream school system [8,9].These parents desired to provide a better education, and they can implement a curriculum and learning environment that works specifically for their children [17,18]. In summary, home education certainly appears to provide an environment that encourages parents to exercise their autonomy in supporting their children’s learning and tailoring their education to individual needs.

Parental resources in support of home schooling encompass a diverse range of activities and programs [4,19]. For instance, families that home school now have the opportunity to engage with virtual learning settings and access a vast array of materials. Furthermore, additional resources encompass field trips, music classes, art programs, sporting activities, speech and debate competitions, and more [12,16,19]. When parents prepare and educate their children, these experiences may influence and instil confidence in them, suggesting the concept of an active child engaging with their environment (e.g., [4,14,16,19].

This perspective aligns with the notion that intervention, as suggested by Bronfenbrenner and Morris [20], can exert a positive influence on the trajectory, context, and outcomes of child development. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system theory, first introduced in 1979, serves as a foundational framework, emphasising the crucial consideration of broader environmental influences on a child’s development. These factors encompass elements like family, community, and societal influences, all of which play crucial roles in shaping a child’s educational journey.

In educational discourse, Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) [21] ecological model offers valuable insights into understanding the motivations behind families embarking on home-education journeys. It also holds the potential to provide a nuanced understanding of how families navigate transitions, particularly in the context of home schooling. This model can be applied by both home-educating families and education professionals to recognise and address the unique circumstances fostering children’s learning within the home-schooling environment.

In short, Bronfenbrenner’s theory (1979 [21]; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2007 [20]) posits that a child’s development is intricately influenced by multiple interacting systems, ranging from immediate microsystems (family and home environments) to larger macrosystems (societal and cultural contexts). Understanding these interconnected layers provides a comprehensive framework for promoting holistic and effective interventions in child development, particularly within the context of home education. Applying this lens to home schooling also allows researchers and educators to gain profound insights into the dynamic interplay of factors affecting a child’s learning and development within the unique context of home schooling.

3. This Study

The aim of this project was to use the Appreciative Inquiry methodology as the main vehicle for providing answers to the following research questions:

- How do home-educating families support their children’s education?

- What do home-educating parents perceive to be best practices in their work with children?

- What changes would families like to see for home education moving forward?

4. Methodology

In pursuit of capturing the perspectives of UK home-educating parents, a naturalistic paradigm was deliberately selected for this study. This choice was made with the intent of reconstructing the reality as perceived by individuals engaged in home education, thereby acknowledging and embracing their unique points of view [22,23]. The foundation guiding this approach to the research investigation was rooted in the principles recommended by Lincoln and Guba (1985) [23], who proposed that within social communities characterised by shared experiences, practices, and activities, an approximation of reality should be constructed to represent the shared understanding of the group [23].

To gain comprehensive insight into the experiences of home-educating families, a qualitative approach was employed. Recognising the significance of understanding the positive aspects of home education, along with uncovering the strengths and resources of home-educating families, the researcher chose the Appreciative Inquiry as the primary methodological framework. The utilisation of a positive psychology lens facilitates the exploration of valuable experiences as perceived by individuals. It involves identifying events that positively contribute to their personal development and contribute to maintaining a positive outlook in their daily lives [24].

In their seminal work, Cooperrider and Srivastva (1987) [25] asserted that groups and organisations alike are socially constructed realities influenced by the forms of inquiry. The efficacy of Appreciative Inquiry in educational research has been demonstrated through its emphasis on strengths to foster capacity building [26,27]. This perspective is relevant to the overarching goal of the research, which is centred on humanistic perspectives, holistic learning, and the intrinsic value of positive experiences.

The Appreciative Inquiry perspective begins with an examination of human strengths and positive individual qualities, exploring their connections with personal experiences, the construction of meaning, and overall functioning and development [26,27]. In this qualitative study, the researcher assumed the role of a human instrument, intending to bring forth the voices of the participants. This approach was deemed applicable in order to actively engage with and understand the lived experiences and perspectives of the participants.

Project Process. Ethical clearance (Ethics Reference UoL2022_10102) was obtained from the researcher’s institutional ethics committee before commencing the study. The research, covering design, participant recruitment text, questionnaire and interview protocol wording, participant information and consent, underwent review and approval by the ethics committee. Data collection and storage adhered to the institution’s standards and the Professional Code of Conduct of the British Educational Research Association (BERA). Informed consent was acquired from all participants, who were free to withdraw from the research at their discretion. All gathered information was treated as confidential. Focus group interviews were conducted with due respect and sensitivity.

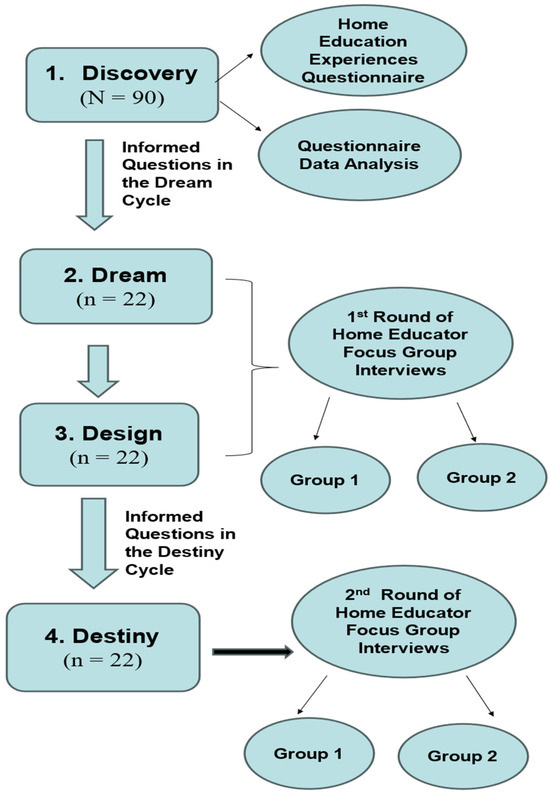

Presently, Appreciative Inquiry comprises four stages delineated as the 4-D cycle—namely, discovery, dreaming, design, and destiny [28]. The current research process was influenced by these four phases, cultivating a heightened awareness for the researcher in articulating study aims, developing instruments, and conducting a comprehensive analysis of the data. The process is summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research method and project process.

As the initial phase of the Appreciative Inquiry process, the primary objective of the Discovery stage was to utilise an online questionnaire to identify and recognise home-educating practices instrumental to student learning. This stage was also used to discern “high points” of the home-education context, as well as what the home-educating parents valued and enjoyed.

To achieve this, a twenty-four-item questionnaire was devised. To validate the questionnaire, three parents not involved in the main study were invited to review the pre-test questionnaire and provide constructive suggestions for improvement. These parents were randomly selected to capture a range of perspectives. Their feedback was integrated to enhance the clarity of the questionnaire for each pre-test participant. Following this, the refined questionnaire underwent additional examination by two field experts for further validation.

The demographic section, covering variables such as age and education, was followed by questions drawn from three widely used and cross-culturally validated surveys [19,29,30]. The following are examples of questions from the instrument: (a) “What do you consider to be the best practices in your work with your children?”, (b) “What types of resources do you have access to that are beneficial for teaching your child?”, and (c) “What other types of support do you receive from others, including family, friends, and other home educators?”.

The questionnaire (Appendix A), distributed through JISC Online Surveys, a secure platform endorsed by the intuition at the time of the study, was finalised and made available online. It required approximately 15 min to complete and included an optional section for volunteering in follow-up interviews. Participants could stay anonymous, providing contact details only if opting for an interview. For data security, responses were anonymised post interview contact, and all data were two-factor authenticated and password-protected.

Participants were recruited through social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, WhatsApp) through posts advertising the questionnaire, by contacting home-education co-ops, and by reaching out to community educational networks. To help potential participants understand the nature of the study, the participant recruitment text included a section explaining the study’s purpose and key terms (e.g., home education, best practices, co-ops). A total of 90 UK home-educating parents participated in the Discovery stage through the questionnaire, with none of them being carers, grandparents, or legal guardians.

Following the Discovery stage, two rounds of appreciative focus group interviews were conducted. The first round aimed to facilitate the Dream and Design stages and occurred two weeks after the completion of the online questionnaire. The interviews took place during a full-day gathering on a Saturday in November at a neutral location (i.e., a local community centre), involving 22 parents, each with over three years of experience in home education. These parents willingly accepted the invitation to partake in the interviews. The second round of focus group interviews centred on the final stage, Destiny, and took place one month after the completion of the Dream and Design stages. Once again, these interviews were conducted in the same community centre with the same participants; there was no attrition, but two participants arrived about 30 min late due to prior commitments.

To ensure that interviewees understood the research process used in the study, the Appreciative Inquiry methodology, as well as key terms such as best home-education practices and relevant examples, were presented before the interviews took place. A brief question-and-answer session was also allocated to clarify any questions that the participants had about the study. Please refer to Appendix B for the interview protocol.

To enhance the focus group discussions during both rounds of interviews, participants were divided into two groups. The researcher and an assistant each facilitated a small group consisting of 11 participants. The assistant, an experienced researcher in education, had received training in Appreciative Inquiry before the study.

In the Discovery stage (Stage 1), the basic themes elicited from the questionnaire were initially synthesised in the form of provocative proposals—affirmatively worded statements, rooted in past experiences of best practice, that challenge the way things currently work (Coghlan et al., 2003 [31]). These statements and other basic themes were then analysed further for organising and global themes. This provided an overview of participants’ perceptions of what constituted best home-education practices, which were used in the next phase: the Dream stage.

The objective of the focus group Interviews during the Dream stage was to extract comprehensive narratives, capturing intricate details of real-life events. The goal was to gather stories that would shed light on the participants’ perceptions of what constitutes best practices in parent-led education. The Dream phase facilitated participants in recalling and articulating the specific aspects of their experiences that they found enjoyable and valuable. This encompassed identifying events, activities, and interactions that significantly contributed to the overall richness of their educational encounters. Building upon the insights gleaned from the questionnaire data, participants envisioned crafting an optimal educational experience for their children as well as an expansive vision for an ideal future in education.

The propositions developed during the Dream phase were then incorporated into the Design phase. These propositions were prioritised and grounded in the reality of what has already been experienced and what may be experienced. In the interviews, participants were asked to formulate provocative propositions—concrete, detailed visions derived from insights gained about past successes; these proposals were then used to plan actions for Stage four: the Destiny stage.

The Destiny phase involved developing and implementing strategies based on what individuals identified as valuable. This fourth and final stage also included collecting information on the implementation of the actions identified in the Design stage.

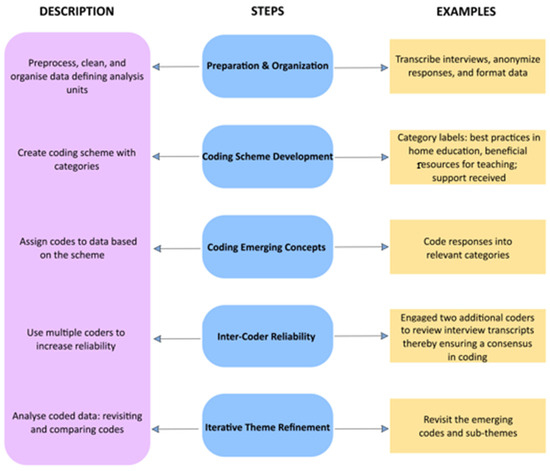

Data Analysis and Research Results. Focusing on participants’ qualitative responses, a content analysis—A recognised method for interpreting written/spoken communication—was applied to identify patterns and themes in their comments [32,33,34]. Following this method, the key steps (i.e., identifying analysis units, coding statements based on emerging concepts, clustering codes into themes, and iteratively refining these themes) for qualitative data analysis were conducted using the Nvivo software (NVivo 14), and Figure 2 provides a detailed overview of the analysis process.

Figure 2.

Content analysis process.

The focus group sessions were recorded using a computer recorder and subsequently transcribed verbatim, with verbatim comments from participants included throughout for illustrative purposes. To enhance the study’s reliability, the researcher engaged two additional coders to review the information gathered from the questionnaire and interview transcripts, ensuring a consensus in the coding.

The following sections present a summary of the findings from each of the 4-D stages, illustrating the systematic approach employed in collecting, analysing, and synthesising the data.

Discovery: Best Home-Education Practices. After analysing the data, five overarching themes emerged as effective home education practices that promoted learning:

- (a)

- Individualised Instruction: Participants consistently highlighted the importance of tailoring instruction to each child’s unique learning style and pace. One participant (Participant 16) eloquently expressed, “We always adapt the curriculum to suit our child’s interests, making learning more engaging and personalised”.

- (b)

- Sharing Instructional Responsibilities with Home-Education Co-ops: Collaborative efforts were evident in participants’ experiences with home-education co-ops. One parent (Participant 20) emphasised, “Being part of a co-op not only broadens the subjects covered but also fosters a sense of community”. This collaborative approach also enhances socialisation in the overall educational experience. A father (Participant 7) who was taking the lead in home educating his two children commented, “We work with other families who are like minded and we teach our children in a tailor-made way that does not undermine our values or take away our family time”.

- (c)

- Creating Conducive Learning Environments: The significance of creating optimal learning environments was a recurring theme. One participant (Participant 4) shared, “Our home learning centre offers a focused and comfortable study area; each child possesses their own ‘personal office’, contributing significantly to their learning experience”. A dedicated space for learning at home reflects an understanding of the importance of a conducive environment for focused study. This theme suggests that home education allows for the customisation of learning spaces, potentially minimising distractions and enhancing concentration.

- (d)

- Developing Close Parent-Child Relationships: Strong parent-child relationships are recognised as a foundational element for positive learning outcomes in home education. The ability to build a closer bond with children through home education facilitates open communication and a deeper understanding of their educational needs. A mother (Participant 2) conveyed that despite the significant challenges in home schooling, a sense of commitment played a role in coping with difficulties when teaching her son mathematics: “I often remind myself that my priority is to teach children, not just subjects”.

- (e)

- Family Commitment to Cultivating Values in Children: Participants emphasised the role of home education in instilling values. One quote reflected this sentiment, “Our commitment goes beyond academics; we see home education as an opportunity to actively shape our children’s character and instil important values” (Participant 17). The acknowledgment of the impact that family values have on a child’s overall development underscores the broader role of education in shaping character.

These key themes collectively highlight the multifaceted nature of effective home-education practices. The illustrative quotes provide a deeper understanding of each theme, highlighting the unique strengths inherent in home-education practices. As these narratives unfold, they consistently emphasise the significance of flexibility, collaboration, personalised environments, close relationships, and a holistic commitment—elements that collectively characterise effective home education.

Dream: Going Beyond the Status Quo And Formulating Visions/Describing Future Scenarios. As indicated earlier, this stage entailed the use of provocative propositions that aimed to promote further momentum in the inquiry. The findings from the Dream stage included the themes elicited from the questionnaire, which were summarised in the form of “provocative proposals”. To stimulate further discussion, the following prompts were provided during the focus group: (a) “What could have made your home-educating experience better?”, (b) “What is your favourite subject to teach, and why?”, (c) “What organisations do you turn to for support in your home-educating experience, and what kinds of supports do you find there?”, (d) “Do you use any services from local schools? If so, can you characterise your experience with those services?”, and (e) “In an ideal homeschool environment, what kinds of activities would effectively facilitate your child’s/children’s learning?” (e.g., activities promoting social/emotional learning, academic development, and physical development).

Five themes emerged from the participant input. (a) Parents expressed a desire to continue using beneficial resources for teaching, such as technology, science experiment sets, and packaged curricula developed by various home-education agencies and companies. (b) Parents were eager to find ways to foster deeper engagement with the subject matter. Although many of them had already been able to utilise their own knowledge and training background, along with support from private tutors and other family members, to aid their children. (c) They aspire to continue educating their children in a safe and supportive learning environment. (d) They expressed a hope to receive more support from like-minded individuals, including extended family members, churches, home-education co-ops, and friends. The final theme, strongly represented as parents spoke about their “dreams”, is evident in the comments below:

“As a father with 3 teenaged children, I have greater expectations; we not only seek an excellent education for our children but also aspire to nurture their holistic development, ultimately leading to a meaningful life. I hope more and more people will respect parents’ right to choose to educate their children themselves and to provide support.” (Participant 14)

“We have enrolled our children in various extracurricular classes. They have been taking piano lessons for more than 10 years and participate in national swimming and math competitions. Additionally, they participate in a chess club and a youth group. We are committed to doing all we can to cultivate academic and social success for our children.” (Participant 21)

“My efforts in home education would be more effective if my husband could fully support it; however, he still disagrees with the decision to homeschool. Hopefully, as he sees the growth and progress our daughter has been making since she left the local school, he will come on board too.” (Participant 19)

Design: Envisioning Results. As the interview progressed into the Design stage, participants were prompted to envision an ideal home-education practice that fosters their children’s learning. The following questions guided participants in brainstorming and designing an optimal future for home education: (a) “What are your dreams and long-term goals for your child’s education? Please briefly describe one or two future scenarios based on these dreams/goals.”, (b) “What do you believe needs to happen for your dreams and goals for your child’s education to materialise?”, (c) “Drawing from the meaningful situations you described earlier, what are the ways to enhance your home-schooling environment so that your child can have more of these meaningful learning experiences?”, (d) “Do you plan to continue implementing the “best practices” you described previously? How can these “best practices” be further improved, if at all?”, and (e) “What changes would you like to see for home education in the UK moving forward?”.

Participants were also encouraged to use stories for annotating the narratives if necessary. Sample stories, derived from the previous stages and the literature, were used to facilitate the process. Using these stories, participants discussed the opportunities, resources, and support they needed to shape their teaching to align with their own talents and their children’s needs.

After analysing the data, four themes surfaced as important results that participants envisioned having: (a) an improved learning environment at home; (b) home-education allowance and support from the government and local schools; (c) developing a subculture in society that cultivates virtues and sound values; and (d) concrete wishes for other parents who are planning to home educate their children.

This first theme emerged from parents’ concerns about the school environment. Parents expressed concern regarding the inflexibility of school academic programs. For example, one participant (Participant 17) emphasised the connection between learning and an optimal environment and what is needed to create such an environment:

“Our child has dyspraxia, and we discovered that schools do not provide the level of accommodation we desire for our child. For instance, during her time in schools, our child was frequently told that she could not do certain things because of her differences. As a result, we have firsthand experience in structuring our home environment to meet her learning needs. However, we do need additional resources to adapt physical education lessons, establish visual routines, and provide reminders.” (Participant 13)

Another parent commented the following:

“We are still in the process of acquiring what we need to create an individualized curriculum for our son, but at the moment, at least he gets to learn at his own pace. Using the mastery learning approach, we are no longer chained to the school schedule!” (Participant 7)

So, what changes would families like to see for home education in the UK moving forward? An analysis of the responses to this question revealed the second theme: support from the government and local schools. Many participants mentioned that many developed countries around the world offer a home-education allowance for parents who choose to opt out of the public school system without compromising home-education freedom. These parents expressed hope that the UK government would learn from other countries such as the USA and New Zealand. They believe subsidies from the government could be utilised to cover the costs of the curricula, supplies, and classes, among other expenses, significantly enhancing the quality of home education. Some parents also emphasised that, as residents of the country, they pay the same amount of taxes regardless of the school choice they make for their children, and therefore, they were “entitled to receive support for the education” of their children. Some parents expressed the desire for their children to be allowed to sit for national exams, such as A-levels, as private candidates without charge. They hope that local schools will make these exams, as well as other competitions, accessible to their children.

The third theme aligns with the existing literature, which noted that many parents expressed concerns about the social climate flourishing in mainstream schools (e.g., [3,15]). Some parents felt that the belief system promoted by public schools is at odds with theirs and undermines the values taught at home. Consequently, they wanted to take on the primary responsibility of imparting the skill sets and virtues that reflect values central to their family life. One parent highlighted the following:

“Parent-led education works for our son; now he gets to hang out with friends who are like-minded, is no longer being laughed at for what he believes, and our son is no longer bullied!” (Participant 16)

Regarding the fourth theme, participants recommended that parents who want to learn more about home education should be open-minded and not solely focus on their children’s academic performance. Instead, they may want to explore a wide range of activities or resources to facilitate their children’s holistic development (e.g., social, emotional, spiritual, physical, and academic). These participants also emphasised that parents should be aware that it is legal to home educate their children, “it is the right thing to do, and it is worthwhile” as one parent (Participant 2) said.

The following comments further illustrate these perspectives:

“Children can get a good education without school; our experience shows that home education enables our children to achieve their full potential. In fact, two of our children received offers from Russell Group universities and are now studying the courses of their first choice.” (Participant 6)

“God gave the children to us, not to the government. As parents, we have the responsibility and privilege to decide the best way to support, encourage, and educate our little ones.” (Participant 4)

“Home-educated students can have a vibrant and healthy social life. Our child has experienced increased social interactions since we withdrew him from school, benefiting from the additional free time. He particularly enjoys forming friendships with peers from his taekwondo class. Moreover, his relationships with us as parents, his siblings, and neighbours have noticeably improved. It is a common misconception that home education implies spending all the time at home, but this is certainly not true.” (Participant 5)

Interestingly, there were a few parents who were more enthusiastic about their views than other home educators, possibly because they perceive their choice and actions to be of great importance. For instance, some parents who feel called to homeschool their children were passionate about their role. These mothers reported that homeschooling helped lead them toward fulfilment and meaning. However, a small number (n = 4) advocated for an “open curriculum and goal-free” approach, embracing each day as it unfolds.

The Design stage was also a phase where participants planned for improvement by setting long-term goals, building on the previous two phases. The following are some of the goals that parents set: (a) setting up learning centres for home-educated students to ensure more children have access to sports activities, practical work, and science experiments; (b) organising home-education co-ops where parents can exchange lessons; (c) developing skills to run both face-to-face and online home-education networks; (d) raising society’s awareness by organising home-education conferences and student conventions so that more people and institutes will respect parents’ right to home school and provide support.

Destiny: Tracking the implementation of changes and reaching the goals in alignment with the vision and values. As indicated earlier, the primary objective of the Destiny stage was to inquire about the plan implementation and the outcomes. After one month had passed since the first focus group interviews, participants were reminded of the goals they had set previously. Participants were also asked to describe their experience with implementing the actions identified in the Design stage and to provide evidence of changes in their home-education practice. Again, participants were split into two groups and were asked to consider the following questions: (a) “What did we achieve since our last meeting?”, (b) “How will we know that we have achieved our goals?”, and (c) “What do we need to do next?”.

Though only one month had passed since the inception of the Destiny stage, the proactive and determined actions taken by the participants reflected their dedication and passion for enhancing their home-education practices. The following are the primary actions taken by these engaged parents: (a) contacting the local council for free access to public libraries; (b) writing to the Department of Education to request a home-education subsidy; (c) reaching out to local schools (both public and private ones) to request opportunities for their children to participate in sport and art activities; (d) enrolling in education courses, covering curriculum design, child development, and intentional community building; and (e) approaching local schools for opportunities for their children to sit for national examinations (e.g., A-levels/ECSE/Scottish Highers and Advanced Highers) as private candidates.

Unexpectedly, some participants expressed the positive impact of the Appreciative Inquiry approach and conveyed appreciation for their involvement in the study. They found the strength-based approach valuable in gaining deeper insights into their home education practices, while the solution-focused orientation provided them with momentum to make positive changes.

The Destiny phase posed the most significant challenges in the study, primarily because some of the goals set by participants during the Design stage had not yet materialised, and the project needed to conclude within a month. Despite these challenges, each of the research questions was adequately dealt with and answered.

5. Discussion

This study employed the Appreciative Inquiry approach to understand how home-schooling families support their children’s learning by strategically and creatively using various resources. The following sections address each of the research questions through the main themes derived from the data.

5.1. How Do Home-Educating Families Support Their Children’s Education?

Through the lens of Appreciative Inquiry, this research uncovered multifaceted strategies employed by home-educating families to support their children’s education. Participants reported utilising various resources to enhance their children’s learning, including technology, science experiment sets, and packaged curricula sourced from home-education agencies and companies. Beyond materials, some discovered the value of (a) establishing a personal study space that fosters a sense of safety and support for their children and (b) seeking additional assistance from like-minded individuals, including extended family members, churches, home-education co-ops, and friends. Parents also underscored the significance of their own knowledge, training background, and support from private tutors and family members as vital resources in aiding their children’s education.

5.2. What Do Home-Educating Parents Perceive to Be Best Practices in Their Work with Children?

Home-educating parents found that creating flexible learning environments tailored to each child’s needs was important. They emphasised the value of a strong family commitment to home education, fostering an environment where learning was embraced as a shared family value. Maintaining close and supportive relationships between parents and children was seen as crucial for a positive learning experience.

Collaborative efforts, particularly in the form of home-education co-ops, were highlighted in their experiences. These initiatives allowed families to work together, sharing resources and experiences, enhancing the educational journey for both parents and children. The sense of community and support within these co-ops were regarded as valuable aspects of home-education best practices.

5.3. What Changes Would Families Like to See for Home Education Moving Forward?

Families envisioned several changes for the future of home education, with recurring themes including (a) an enhanced learning environment at home: parents expressed a desire for an improved learning atmosphere within their homes, emphasising a conducive space that nurtures holistic development in children—covering social, emotional, spiritual, physical, and academic aspects; (b) government and school support: many families were keen on receiving home-education allowances and support from both the government and local schools and believed that formal recognition and assistance can contribute significantly to the success of home-education endeavours; (c) cultivating virtues and values in society: participants advocated for the development of a subculture in society that prioritises virtues and sound values and saw this as instrumental in creating an environment that aligns with the principles and goals of home education; and (d) concrete guidance for prospective home-educating parents: families offered suggestions for parents considering home education, recommending an open-minded approach. Rather than solely focusing on academic performance, they encouraged an exploration of diverse activities and resources to foster children’s comprehensive development. Emphasising the importance of awareness, participants highlighted that parents should be informed about the legality of home education.

In summary, families envisioned a future for home education that embraces an enriched learning environment, government and school support, a societal focus on virtues, and practical guidance for those embarking on the home-education journey.

6. Implications

The findings of the study have implications for policy, practice, and research in children’s development. They can be utilised to facilitate collaboration between homes and schools, as well as partnerships between families and professional educators. Furthermore, as an increasing number of families choose to home educate their children, these insights are relevant and beneficial to the home-education movement and education policy in the UK and beyond.

These findings serve as a basis for suggesting learning principles for a curriculum that holds the promise of offering students constructive learning experiences, fostering deeper and more holistic developments, and promoting intrinsic motivation. Moreover, this study reaffirms the existing home-schooling literature, highlighting that sharing instructional responsibilities with home-education co-ops and other families is an effective alternative to public education.

In addition, as mentioned earlier, studies on home education in the UK remain sparse. While much of the research on home-educating families focuses on parental motivational factors, few studies investigate the learning resources and strategies used by home-educating families. This study contributes to the literature by exploring what home-educating parents perceive as best practices in their work with children. The results can also be utilised to inform home-education scholars, advocates, and practitioners of strategies and affordances beneficial for home-education learning environments.

Another important implication of the study stems from the uniqueness of the research methodology. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first study on home education in the UK that utilised the Appreciative Inquiry method. As demonstrated in the literature, this study affirms that Appreciative Inquiry, as a proven, collaborative, strength-based approach, can effectively facilitate positive change and build capacity in learning environments both at home and school.

7. Limitations

As with other studies, there are limitations worthy of acknowledgment. This research was constrained by a limited participant pool from one country. Future studies should include diverse global samples for broader insights, explore the driving factors of home-education success, and track the development of home-educated students over time.

Secondly, as the Destiny stage represents an ongoing phase where participants consistently enact changes, closely monitor their progress, and actively participate in new dialogues and appreciative inquiries [34], the study could have been strengthened through an additional session with home schooling parents to clarify how progress would be tracked. Additionally, future research exploring home education through in-home observations may offer greater depth and insights. The consideration of potential social desirability bias in the questionnaires and interviews is also crucial.

8. Conclusions

In summary, despite its limitations, this study serves as a foundational step for extended research on home education, carrying important implications for home schoolers not only in the UK but also globally. Notably, there is significant potential to explore critical research questions concerning educational policies, home-education practices, environments, and other factors influencing the success of parent-led education. These questions deserve further exploration, presenting an exciting opportunity for future research in the field of home education.

Funding

This research has received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the UoL Human Ethics Committee (protocol code UoL2022_10102, approved on 24 November 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable to the public due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Online Questionnaire

Background

- Prior to home education what job did you do?

- Why did you decide to home educate?

Home Education Learning Environment, Practices & Resources

- 3.

- What type of home education model(s) have your children experienced? Please select all that apply.

- ○

- Private school-Home education partnership

- ○

- Home education co-op support group

- ○

- Home education where I am the primary educator

- ○

- Unschooling model where my child directs most, if not all, learning

- ○

- Other

- 4.

- Why did you choose to home educate your children using the model you mentioned above? Please select all that apply.

- ○

- Religious values

- ○

- Undesirable academic outcomes found elsewhere

- ○

- Undesirable social influences found elsewhere

- ○

- Safety of learning environment (drugs, gangs, etc.)

- ○

- Child with special needs

- ○

- Other (please indicate here___________________)

- 5.

- Who is most involved in facilitating the child’s learning?

- 6.

- What approach do you use?

- 7.

- What resources do you use?

- 8.

- What types of resources are beneficial for teaching your child?

- 9.

- What types of online resources are used to support home education? Please select all that apply.

- ○

- Websites recommended from a search engine

- ○

- Social media (Facebook, Twitter, etc.)

- ○

- Tutoring or self-paced curriculum

- ○

- Virtual academy

- ○

- Other

- 10.

- What do you perceive to be best practices in your work with your children?

- 11.

- How has home education affected the relationship between your child and the other members of your family?

- 12.

- Please describe two meaningful home school situations you and your child experienced and wanted more of.

- What happened? Who was involved? Why do you think you remember it?

- Did you and/or your child learn something? If so, what was it? How did you feel?

- 13.

- What do you like about your home education style?

- 14.

- What does a typical day or week look like for your home education schedule?

- 15.

- How do you help foster & cultivate learning for your child?

- 16.

- What other types of support do you receive from others, including family, friends, and other home educators?

- 17.

- Do you get pleasure from this work (i.e., home education) as well as feeling confident?

- 18.

- What do you think are the benefits of home education?

- 19.

- Are there any further comments you would like to make in relation to this research study?

Demographics

- 20.

- What is your sexual orientation?

- ○

- Bi

- ○

- Gay Man

- ○

- Gay Woman/Lesbian

- ○

- Heterosexual/Straight

- ○

- Prefer to self-describe: _______________________

- ○

- Prefer not to say

- 21.

- What is the post code of your address?

- 22.

- How many children do you home educate?

- ○

- 1

- ○

- 2

- ○

- 3

- ○

- 4

- ○

- 5 or more

- 23.

- How long have you home educated your children?

- ○

- This is my first year

- ○

- Between 2–3 years

- ○

- Between 4–5 years

- ○

- Between 6–7 years

- ○

- 8 years or more

- 24.

- Will you be happy to be contacted regarding taking part in an interview?

- ○

- Yes (if your answer is yes, please write down your email address here___________________ to allow me to contact you and I will email you the consent form for the interview)

- ○

- No

Appendix B. Focus Group Interview Protocol

The focus group interview contains the last three stages of the 4-D cycle (i.e., Discover, Dream, Design, and Destiny) of the Appreciative Inquiry process. The interview protocol was as follows:

- I.

- Discovery: discerning ‘high points’ of a context, what you value and discuss why situations are important. Questions provided in the online questionnaire.

- II.

- Dream: going beyond status quo and formulating visions and describing future scenarios.

- 1.

- What are your dreams and long-term goals for your child’s education?

- 2.

- Please briefly describe one or two future scenarios based on these dreams/goals.

- III.

- Design: Planning for improvement through setting goals, building on the previous two phases; formulating activities contributing to reaching the goals

- 3.

- What are your dreams and long-term goals for your child’s education?

- 4.

- What do you think needs to take place/to be done for your dreams and goals for your child’s education to come true?

- 5.

- Based on the meaning situations you described earlier, what are the ways to improve your home-school so that your child can experience more of these “meaningful home school situations”?

- 6.

- Will you continue to implement the “best practices” you described previously? What are the ways to further improve these “best practices”, if any?

- 7.

- Describe ways to improve the learning environment in your home.

- What kinds of activities or resources would you like to use to help facilitate your child’s social development?

- What kinds of activities or resources do you use to help facilitate your child’s academic development?

- What kinds of activities or resources do you use to help facilitate your child’s emotional development?

- What kinds of activities or resources do you use to help facilitate your child’s spiritual development?

- 8.

- What opportunities, resources, and support do you need to shape your teaching to align with your own talents and your children’s needs?

- 9.

- What changes would families like to see for home education in the UK moving forward?

- IV.

- Destiny: Tracking the implementation of changes and reaching the goals in alignment with the vision and values.

- 10.

- What did we achieve since our last meeting?

- 11.

- How will we know that we have achieved our goals?

- 12.

- What do we need to do next?

References

- Association of Directors of Children’s Services. Elective Home Education Survey Report 2021; Association of Directors of Children’s Services: Manchester, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, G.L. Elective Home Schooling in England: A Policy in Need of Reform? ERIC Number: ED608374; Bulgarian Comparative Education Society: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lees, H.E. Education without Schools: Discovering Alternatives; The Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T. Through the lens of home-educated children: Engagement in education. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2013, 29, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teachers To Your Home. Facts about Homeschooling in the UK: A Guide for Parents. 2023. Available online: https://www.teacherstoyourhome.com/uk/blog/home-schooling-in-the-ukaguideforparents#:~:text=In%202023%2C%20it%20was%20estimated,success%2C%20both%20academically%20and%20socially (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Department for Education. Schools, Pupils and Their Characteristics. 2023. Available online: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-pupils-and-their-characteristics (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- UK Legislation. Education Act Chapter I; The Stationery Office: London, UK, 1996. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1996/56/section/7 (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Forlin, C.; Chambers, D. Is a whole school approach to inclusion really meeting the needs of all learners? Home-schooling parents’ perceptions. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillie, S. Transition away from school: A framework to support professional understandings. Int. J. Educ. Life Transit. 2023, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, N.; Doughty, J.; Slater, T.; Forrester, D.; Rhodes, K. Home education for children with additional learning needs—A better choice or the only option? Educ. Rev. 2020, 72, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, C.; Baginsky, M.; Manthorpe, J.; Driscoll, J. Home education in England: A loose thread in the child safeguarding net? In Social Policy and Society; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, C. Home-School Learning Resources: A Guide for Home-Educators, Teachers, Parents, and Librarians; Facet: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, L. Widening access for home-educated applicants to higher education institutions in England. Int. J. Educ. Life Transit. 2023, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, B.D. Home schooling for individuals’ gain and society’s common good. Peabody J. Educ. 2000, 75, 72–293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ray, B.D. School Choice: Separating Fact from Fiction; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, B.D. Research Facts on Homeschooling. 2023. Available online: https://www.nheri.org/research-facts-on-homeschooling/ (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Jolly, J.L.; Matthews, M.S.; Nester, J. Homeschooling the gifted: A parent’s perspective. Gift. Child Q. 2012, 57, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.L. Getting to know homeschoolers. J. Coll. Admiss. 2016, 233, 40–43. Available online: http://www.nacacnet.org (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Sabol, J.M. Homeschool Parents’ Perspective of the Learning Environment: A Multiple-Case Study of Homeschool Partnerships. Ph.D. Thesis, Pepperdine University, Malibu, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P. The bioecological model of human development. In Handbook of Child Psychology, 6th ed.; Lerner, Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.; Guba, E. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cooperrider, D.L.; Avital, M. Introduction: Advances in Appreciative Inquiry—Constructive Discourse and Human Organization; Emerald Group: Bradford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cooperrider, D.L.; Srivastva, S. Appreciative inquiry in organizational life. In Research in Organizational Change and Development; Woodman, R.W., Pasmore, W.A., Eds.; JAI Press: Stamford, CT, USA, 1987; Volume 1, pp. 129–169. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, B. ‘One expertise among many’ working appreciatively to make miracles instead of finding problems. J. Nurs. Res. 2006, 11, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooperrider, D.I.; Whitney, D. Appreciative Inquiry: A Positive Revolution in Change; Berrett-Kochler: Oakland, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cooperrider, D.L.; Stavros, J.M.; Whitney, D.K. The Appreciative Inquiry Handbook: For Leaders of Change; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Noel, A.; Stark, P.; Redford, J. Parent and Family Involvement in Education, from the National Household Education Surveys Program of 2012 (NCES 2013-028); National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education: Washington, DC. USA, 2013.

- Ray, B.D. African American homeschool parents’ motivations for homeschooling and their Black children’s academic achievement. J. Sch. Choice 2015, 9, 71–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, A.T.; Preskill, H.; Catsambas, T. An overview of appreciative inquiry in evaluation. New Dir. Eval. 2003, 100, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 3rd ed.; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd ed.; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 8th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).