Assessing the Linguistic Creativity Domain of Last-Year Compulsory Secondary School Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Creativity and Its Role in Education

1.2. Towards Creativity Assessment Instruments: Which Facet of Creativity Is Evaluated?

1.3. Focusing on the Assessment of the Linguistic Domain of Creativity

- What is the creative performance, in the linguistic domain, of Spanish students in their last year of compulsory secondary school?

- Are there any differences according to the gender of students?

- Are the three linguistic creativity tasks (metaphor generation, naming unrelated words and alternate uses task) correlated?

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments and Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

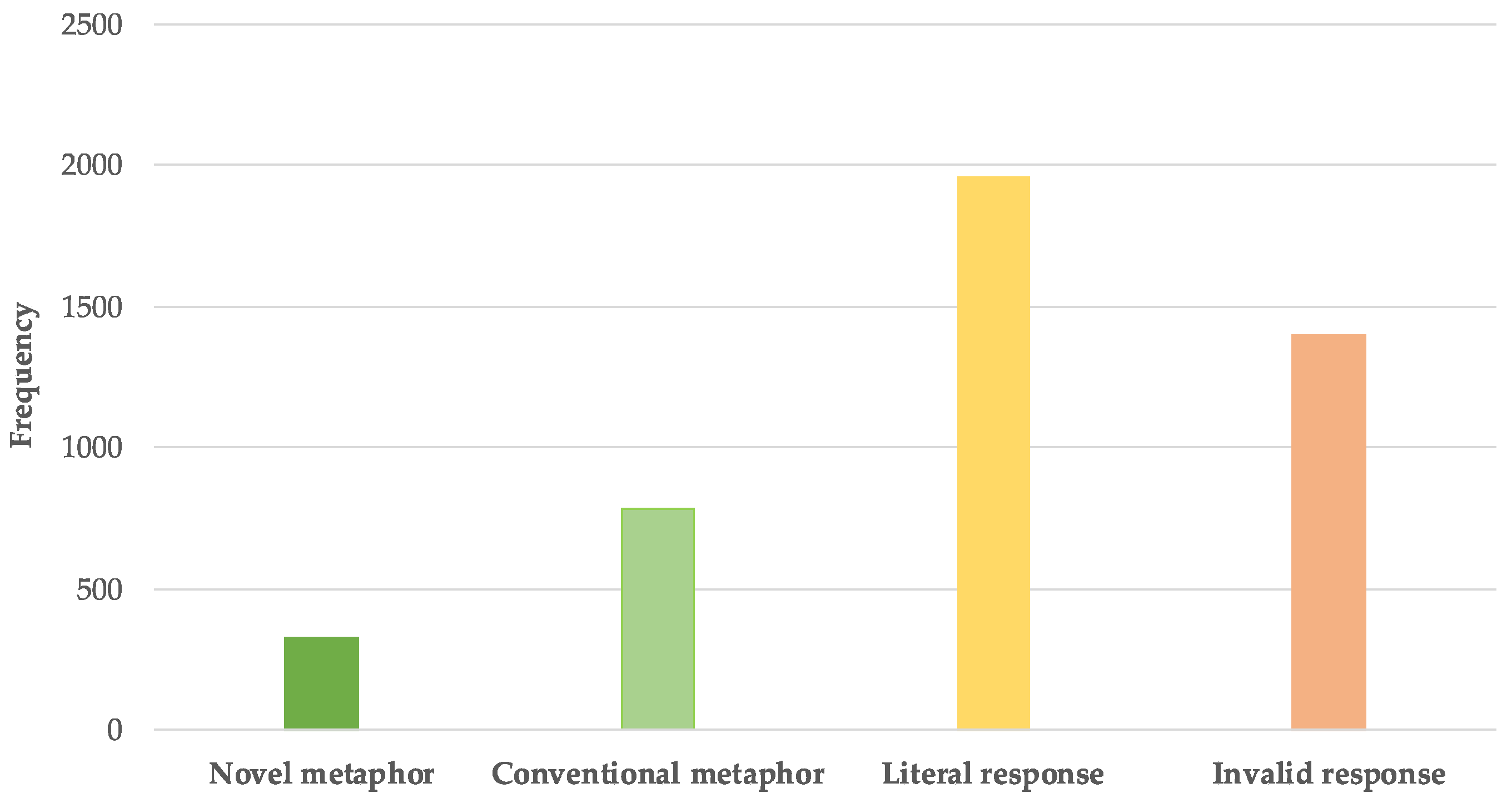

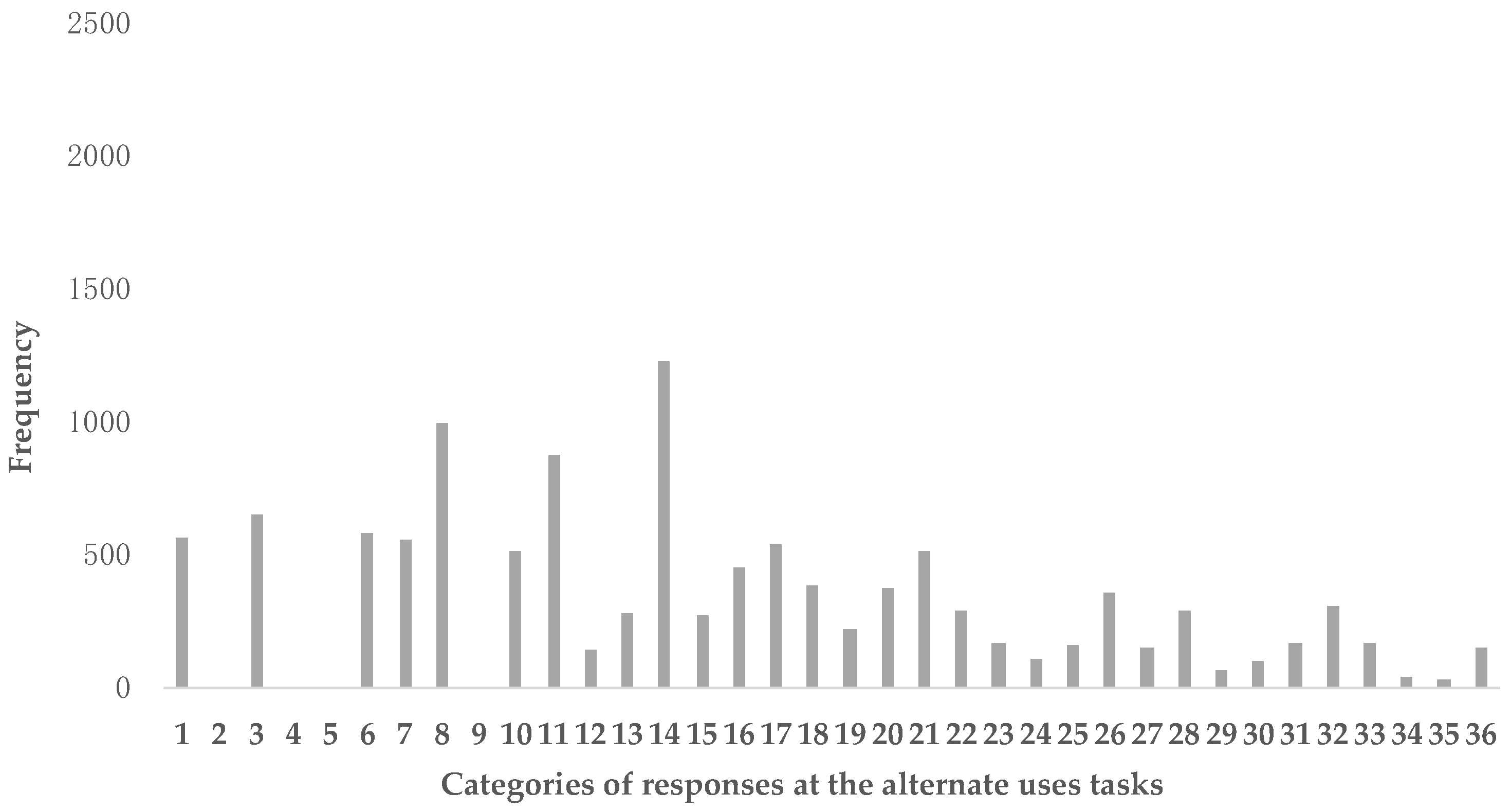

3.1. Divergent Thinking Tasks and Creative Metaphor Generation Performance

3.2. Differences According to Gender

3.3. Correlation between Divergent Thinking Tasks and Creative Metaphor Generation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category of Responses | Description of the Uses Proposed by Students |

|---|---|

| 1 | Blowing, smelling, slurping |

| 2 | Conduction |

| 3 | Playing, toys |

| 4 | Personal accessories |

| 5 | Storing |

| 6 | Attacking, weapons |

| 7 | Protecting, shelter, isolation |

| 8 | Holding |

| 9 | Scholarly uses |

| 10 | Sports |

| 11 | Construction |

| 12 | Sanitary and scientific uses |

| 13 | Looking into |

| 14 | General tools |

| 15 | Decoration |

| 16 | Home tools |

| 17 | Clothing |

| 18 | Grabbing, catching, dragging |

| 19 | Tying |

| 10 | Making noises |

| 21 | Travelling, transporting |

| 22 | Communication |

| 23 | Job tools (such as carpentry) |

| 24 | Molding |

| 25 | Floating |

| 26 | Indicating, lightening |

| 27 | Hiding |

| 28 | Recycling, change of state |

| 29 | Climbing, going up |

| 30 | Geometric assemblies |

| 31 | Connecting |

| 32 | Food |

| 33 | Body parts |

| 34 | Measuring |

| 35 | Magic or fantasy tools |

| 36 | Other uses not fitting in any of the above categories |

References

- Thornhill-Miller, B.; Camarda, A.; Mercier, M.; Burkhardt, J.M.; Morisseau, T.; Bourgeois-Bougrine, S.; Vinchon, F.; El Hayek, S.; Augereau-Landais, M.; Mourey, F.; et al. Creativity, Critical Thinking, Communication, and Collaboration: Assessment, Certification, and Promotion of 21st Century Skills for the Future of Work and Education. J. Intell. 2023, 11, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J.C.; Glaveanu, V.P. A Review of Creativity Theories: What Questions Are We Trying to Answer? In The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity, 2nd ed.; Kaufman, J.C., Sternberg, R.J., Eds.; Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, M.I. Creativity and culture. J. Psychol. 1953, 36, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runco, M.A.; Jaeger, G.J. The Standard Definition of Creativity. Creat. Res. J. 2012, 24, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbot, B.; Hass, R.W.; Reiter-Palmon, R. Creativity assessment in psychological research: (Re)setting the standards. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2019, 13, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guildford, J.P. Creativity. Am. Psychol. 1950, 5, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaveanu, V.P.; Hanchett-Hanson, M.; Baer, J.; Barbot, B.; Clapp, E.P.; Corazza, G.E.; Hennessey, B.; Kaufman, J.C.; Lebuda, I.; Lubart, T.; et al. Advancing Creativity Theory and Research: A Socio-cultural Manifesto. J. Creat. Behav. 2020, 54, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, J. Domain specificity and the limits of creativity theory. J. Creat. Behav. 2012, 46, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunavsky, A.; Poppenk, J. Neuroimaging predictors of creativity in healthy adults. Neuroimage 2020, 206, 116292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccia, M.; Piccardi, L.; Palermo, L.; Nori, R.; Palmiero, M. Where do bright ideas occur in our brain? Meta-analytic evidence from neuroimaging studies of domain-specific creativity. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, J.; Kaufman, J.C. Bridging generality and specificity: The amusement park theoretical (APT) model of creativity. Roeper Rev. 2005, 27, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batey, M.; Furnham, A. Creativity, intelligence, and personality: A critical review of the scattered literature. Genet. Soc. Gen. Psychol. Monogr. 2006, 132, 355–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romo, M.; Sanchez-Ruiz, M.J.; Alfonso-Benlliure, V. Creativity and personality across domains: A critical review. UB J. Psychol. 2017, 47, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. Four ways five factors are basic. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1992, 13, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Pillemer, J. Perspectives on the social psychology of creativity. J. Creat. Behav. 2012, 46, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, M. An analysis of creativity. Phi Delta Kappa 1961, 42, 305–310. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, J.C.; Beghetto, R.A. Beyond big and little: The four C model of creativity. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2009, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmetty, S.; Collin, K. Self-directed learning in creative activity: An ethnographic study in technology-based work. J. Creat. Behav. 2021, 55, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent-Lancrin, S.; González-Sancho, C.; Bouckaert, M.; De Luca, F.; Fernández- Barrerra, M.; Jacotin, G.; Urgel, J.; Vidal, Q. Fostering Students’ Creativity and Critical Thinking: What It Means in School; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tzachrista, M.; Gkintoni, E.; Halkiopoulos, C. Neurocognitive Profile of Creativity in Improving Academic Performance. A Scoping Review. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LOMLOE: Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de Diciembre, Por la Que Se Modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de Mayo, de Educación. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2020-17264 (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Wang, H.H.; Deng, X. The Bridging Role of Goals between Affective Traits and Positive Creativity. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, A.; Dikmen, S.; Karakaya, Y.E. Bibliometric Mapping of Research on Thinking Skills and Creativity in Education. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 2023, 9, 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H.T.; Hammond, J.A.; Grohman, M.G.; Katz-Buonincontro, J. Creativity measurement in undergraduate students from 1984–2013: A systematic review. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2019, 13, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwowski, M.; Han, M.H.; Beghetto, R.A. Toward dynamizing the measurement of creative confidence beliefs. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2019, 13, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, S.; Runco, M.A. Divergent thinking: New methods, recent research, and extended theory. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2019, 13, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, K.N.; Silvia, P.J. Ecological assessment in research on aesthetics, creativity, and the arts: Basic concepts, common questions, and gentle warnings. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2019, 13, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbot, B.; Said-Metwaly, S. Is There Really a Creativity Crisis? A Critical Review and Meta-analytic Re-Appraisal. J. Creat. Behav. 2021, 55, 696–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, H.; Reiter-Palmon, R.; Kaufman, J.C. Norming the Muses: Establishing the Psychometric Properties of the Kaufman Domains of Creativity Scale. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2021, 39, 680–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivisto, M.; Grassini, S. Best humans still outperform artificial intelligence in a creative divergent thinking task. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvia, P.J.; Winterstein, B.P.; Willse, J.T.; Barona, C.M.; Cram, J.T.; Hess, K.I.; Martinez, J.L.; Richard, C.A. Assessing creativity with divergent thinking tasks: Exploring the reliability and validity of new subjective scoring methods. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2008, 2, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Kerr, B.A.; Emler, T.E.; Birdnow, M. A Critical Review of Assessments of Creativity in Education. Rev. Res. Educ. 2022, 46, 288–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrance, E.P. Predictive validity of the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking. J. Creat. Behav. 1972, 6, 236–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaty, R.E.; Johnson, D.R. Automating creativity assessment with SemDis: An open platform for computing semantic distance. Behav. Res. Methods 2021, 53, 757–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbot, B. The dynamics of creative ideation: Introducing a new assessment paradigm. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runco, M.A. Commentary: Divergent thinking is not synonymous with creativity. Psychol. Aesthet. Create. Arts 2008, 2, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter-Palmon, R.; Forthmann, B.; Barbot, B. Scoring divergent thinking tests: A review and systematic framework. Psychol. Aesthet. Create. Arts 2019, 13, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runco, M.A.; Acar, S. Divergent thinking as an indicator of creative potential. Creat. Res. J. 2012, 24, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J.C.; Glaveanu, V.P.; Baer, J. The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity across Domains; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said-Metwaly, S.; Van den Noortgate, W.; Kyndt, E. Approaches to measuring creativity: A systematic literature review. Creat. Theor. Res. Appl. 2017, 4, 238–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomsky, N. The Reasons of State; Penguin: London, UK, 2003; p. 402. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, G. Two ideas of creativity. In Evidence. Experiment and Argument in Linguistics and Philosophy of Language; Hinton, M., Ed.; Peter Lang Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergs, A. What, if anything, is linguistic creativity. Gestalt Theory 2019, 41, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso-Benlliure, V.; Mínguez-López, X. Literary Competence and Creativity in Secondary Students. ReRev. Interuniv. Formación Profr. 2022, 97, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mednick, S.A. The associative basis of the creative process. Psychol. Rev. 1962, 69, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaty, R.E.; Kenett, Y.N.; Hass, R.W.; Schacter, D.L. Semantic memory and creativity: The costs and benefits of semantic memory structure in generating original ideas. Think. Reason. 2023, 29, 305–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.A.; Nahas, J.; Chmoulevitch, D.; Cropper, S.J.; Webb, M.E. Naming unrelated words predicts creativity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2022340118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKerracher, A. Understanding creativity, one metaphor at a time. Creat. Res. J. 2016, 28, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glucksberg, S.; McGlone, M.S.; Manfredi, D. Property attribution in metaphor comprehension. J. Mem. Lang. 1997, 36, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.A. Semantic memory: A review of methods, models, and current challenges. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2021, 28, 40–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenett, Y.N.; Faust, M. A semantic network cartography of the creative mind. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2019, 23, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levorato, M.C.; Cacciari, C. The creation of new figurative expressions: Psycholinguistic evidence in Italian children, adolescents and adults. J. Child Lang. 2002, 29, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melogno, S.; Pinto, M.A.; Levi, G. Metaphor and metonymy in ASD children: A critical review from a developmental perspective. Res. Autism. Spectr. Disord. 2012, 6, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winner, E.; McCarthy, M.; Gardner, H. The ontogenesis of metaphor. In Cognition and Figurative Language; Honeck, R.P., Hoffman, R.R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1980; pp. 341–347. [Google Scholar]

- Kasirer, A.; Mashal, N. Fluency or similarities? Cognitive abilities that contribute to creative metaphor generation. Creat. Res. J. 2018, 30, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraca, J.; Poveda, B.; Artola, T.; Mosteiro, P.; Sánchez, N.; Ancillo, I. Three Versions of a new test for assessing creativity in Spanish population (PIN-N, PIC-J, PIC-A). In Proceedings of the ECHA Conference, Paris, France, 22 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Artola, T.; Barraca, J.; Martín, C.; Mosteiro, P.; Ancillo, I.; Poveda, B. Prueba de Imaginación Creativa para Jóvenes; Hogrefe TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for Behavioral Sciences; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistic Using SPPS; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pont-Niclòs, I.; Martín-Ezpeleta, A.; Echegoyen-Sanz, Y. The Turning Point: Scientific Creativity Assessment and Its Relationship with Other Creative Domains in First Year Secondary Students. J. Pendidik. IPA Indones. 2023, 12, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedek, M.; Jauk, E.; Fink, A.; Koschutnig, K.; Reishofer, G.; Ebner, F.; Neubauer, A.C. To create or to recall? Neural mechanisms underlying the generation of creative new ideas. Neuroimage 2014, 88, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Kenett, Y.N.; Zhuang, K.; Liu, C.; Zeng, R.; Yan, T.; Huo, T.; Qiu, J. The relation between semantic memory structure, associative abilities, and verbal and figural creativity. Think. Reason. 2020, 27, 268–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A. Gender and creativity: An overview of psychological and neuroscientific literature. Brain Imaging Behav. 2016, 10, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.L.; Barbot, B. Gender differences in creativity: Examining the greater male variability hypothesis in different domains and tasks. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 174, 110661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, J.; Kaufman, J.C. Gender differences in creativity. J. Creat. Behav. 2011, 42, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artola, T.; Sastre, S.; Jiménez-Blanco, A.; Alvarado, J.M. Evaluación de las actitudes, motivación e intereses lectores en preadolescentes y adolescentes. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 19, 651–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.L.; Said-Metwaly, S.; Camarda, A.; Barbot, B. Gender differences and variability in creative ability: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the greater male variability hypothesis in creativity. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2023; advanced online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pifarré-Turmo, M.; Cujba, A.; Sanuy-Burgués, J.; Martí Ros, L. Evaluación del desarrollo de la creatividad en Secundaria con el Test PIC-J. In Proceedings of the VIII Congreso Internacional de Psicología y Educación, Alicante, Spain, 15–17 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, J. The importance of domain-specific expertise in creativity. Roeper Rev. 2015, 37, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.L.; Kaufman, J.C. Values across creative domains. J. Creat. Behav. 2021, 55, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappe, D.L.; Chiappe, P. The role of working memory in metaphor production and comprehension. J. Mem. Lang. 2007, 56, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowdle, B.F.; Gentner, D. The career of metaphor. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 112, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menashe, S.; Leshem, R.; Heruti, V.; Kasirer, A.; Yair, T.; Mashal, N. Elucidating the role of selective attention, divergent thinking, language abilities, and executive functions in metaphor generation. Neuropsychologia 2020, 142, 107458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenett, Y.N. What can quantitative measures of semantic distance tell us about creativity? Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2019, 27, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaty, R.E.; Johnson, D.R.; Zeitlen, D.C.; Forthmann, B. Semantic distance and the alternate uses task: Recommendations for reliable automated assessment of originality. Creat. Res. J. 2022, 34, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kenett, Y.N.; Hu, W.; Beaty, R.E. Flexible semantic network structure supports the production of creative metaphor. Creat. Res. J. 2021, 33, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; He, R.; Sun, J.; Ding, K.; Wang, X.; He, L.; Zhuang, K.; Lloyd-Cox, J.; Qiu, J. Common brain activation and connectivity patterns supporting the generation of creative uses and creative metaphors. Neuropsychologia 2023, 181, 108487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, H.B.; Lubart, T.I. Scientific creativity: Divergent and convergent thinking and the impact of culture. J. Creat. Behav. 2019, 53, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.; Martin, A.J.; Anderson, M.; Gibson, R.; Liem, G.A.; Sudmalis, D. Young people’s creative and performing arts participation and arts self-concept: A longitudinal study of reciprocal effects. J. Creat. Behav. 2018, 52, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J.C. Counting the muses: Development of the Kaufman Domains of Creativity Scale (K-DOCS). Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2012, 6, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisondo, R.C. Creative Actions Scale: A Spanish scale of creativity in different domains. J. Creat. Behav. 2021, 55, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, K.N.; Beghetto, R.A.; Kaufman, J.C. Creativity in the Classroom: Advice for Best Practices. In Homo Creativus; Lubart, T., Botella, M., Bourgeois-Bougrine, S., Caroff, X., Guegan, J., Mouchiroud, C., Nelson, J., Zenasni, F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root-Bernstein, R.; Root-Bernstein, M. People, Passions, Problems: The Role of Creative Exemplars in Teaching for Creativity, In Creative Contradictions in Education: Cross Disciplinary Paradoxes and Perspectives; Beghetto, R.A., Sriraman, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D. Creativity in Education: Teaching for Creativity Development. Psychology 2019, 10, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echegoyen-Sanz, Y.; Martín-Ezpeleta, A. Creativity and ecofeminism in teacher training. Qualitative analysis of digital stories. Profr. Rev. Currículum Y Form. Profr. 2021, 25, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Ezpeleta, A.; Fuster-García, C.; Vila-Carneiro, Z.; Echegoyen-Sanz, Y. Read to think creatively (COVID-19): Relationship between reading and creativity in teachers in training. Rev. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2022, 97, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Creativity Test | Min | Max | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naming unrelated words | 64.4 | 90.8 | 79.3 | 4.4 |

| Metaphor generation * | 1 | 25 | 11.2 | 4.6 |

| Alternate Uses Task (Total) * | 3 | 89 | 33.6 | 16.9 |

| Alternate Uses Task (Fluidity) * | 1 | 35 | 12.8 | 6.3 |

| Alternate Uses Task (Flexibility) * | 1 | 21 | 8.8 | 3.6 |

| Alternate Uses Task (Originality) * | 0 | 42 | 12.0 | 7.7 |

| Creativity Test | Gender | Mean | SD | z | p | g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naming unrelated words | Female | 79.08 | 4.17 | 0.94 | 0.34 | - |

| Male | 79.51 | 4.71 | ||||

| Metaphor generation * | Female | 11.76 | 4.65 | 2.40 | 0.01 ** | 0.11 |

| Male | 10.54 | 4.37 | ||||

| Alternate Uses Task (Total) * | Female | 36.75 | 17.07 | 3.60 | <0.001 *** | 0.17 |

| Male | 30.37 | 16.10 |

| Creativity Test | Naming Unrelated Words | Metaphor Generation | Alternate Uses Task |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naming unrelated words | 1 | 0.0108 * | 0.030 |

| Metaphor generation * | 0.108 * | 1 | 0.351 ** |

| Alternate Uses Task (Total) * | 0.030 | 0.351 ** | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pont-Niclòs, I.; Echegoyen-Sanz, Y.; Martín-Ezpeleta, A. Assessing the Linguistic Creativity Domain of Last-Year Compulsory Secondary School Students. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020153

Pont-Niclòs I, Echegoyen-Sanz Y, Martín-Ezpeleta A. Assessing the Linguistic Creativity Domain of Last-Year Compulsory Secondary School Students. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(2):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020153

Chicago/Turabian StylePont-Niclòs, Isabel, Yolanda Echegoyen-Sanz, and Antonio Martín-Ezpeleta. 2024. "Assessing the Linguistic Creativity Domain of Last-Year Compulsory Secondary School Students" Education Sciences 14, no. 2: 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020153

APA StylePont-Niclòs, I., Echegoyen-Sanz, Y., & Martín-Ezpeleta, A. (2024). Assessing the Linguistic Creativity Domain of Last-Year Compulsory Secondary School Students. Education Sciences, 14(2), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020153