Digital Competence for Pedagogical Integration: A Study with Elementary School Teachers in the Azores

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

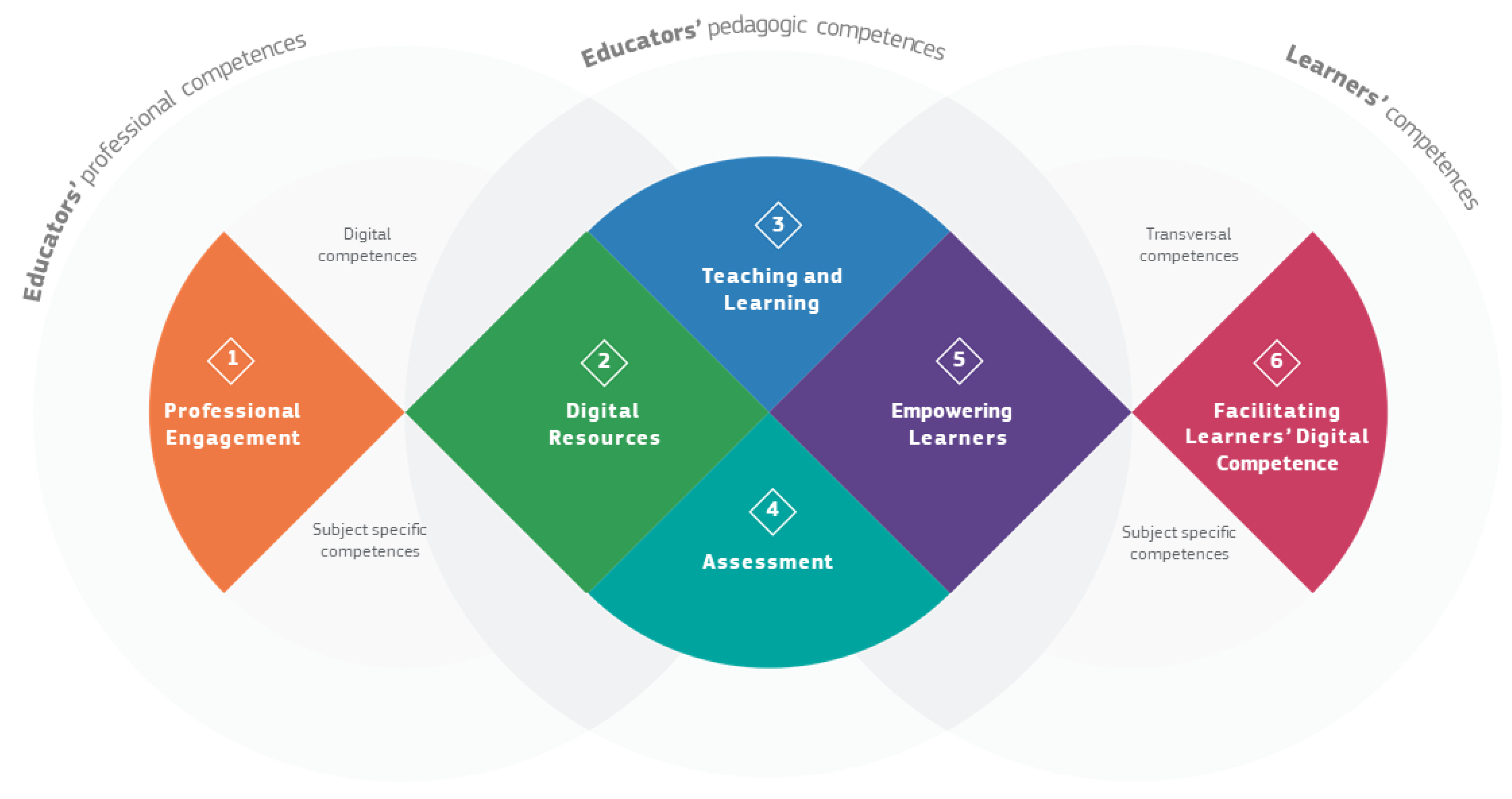

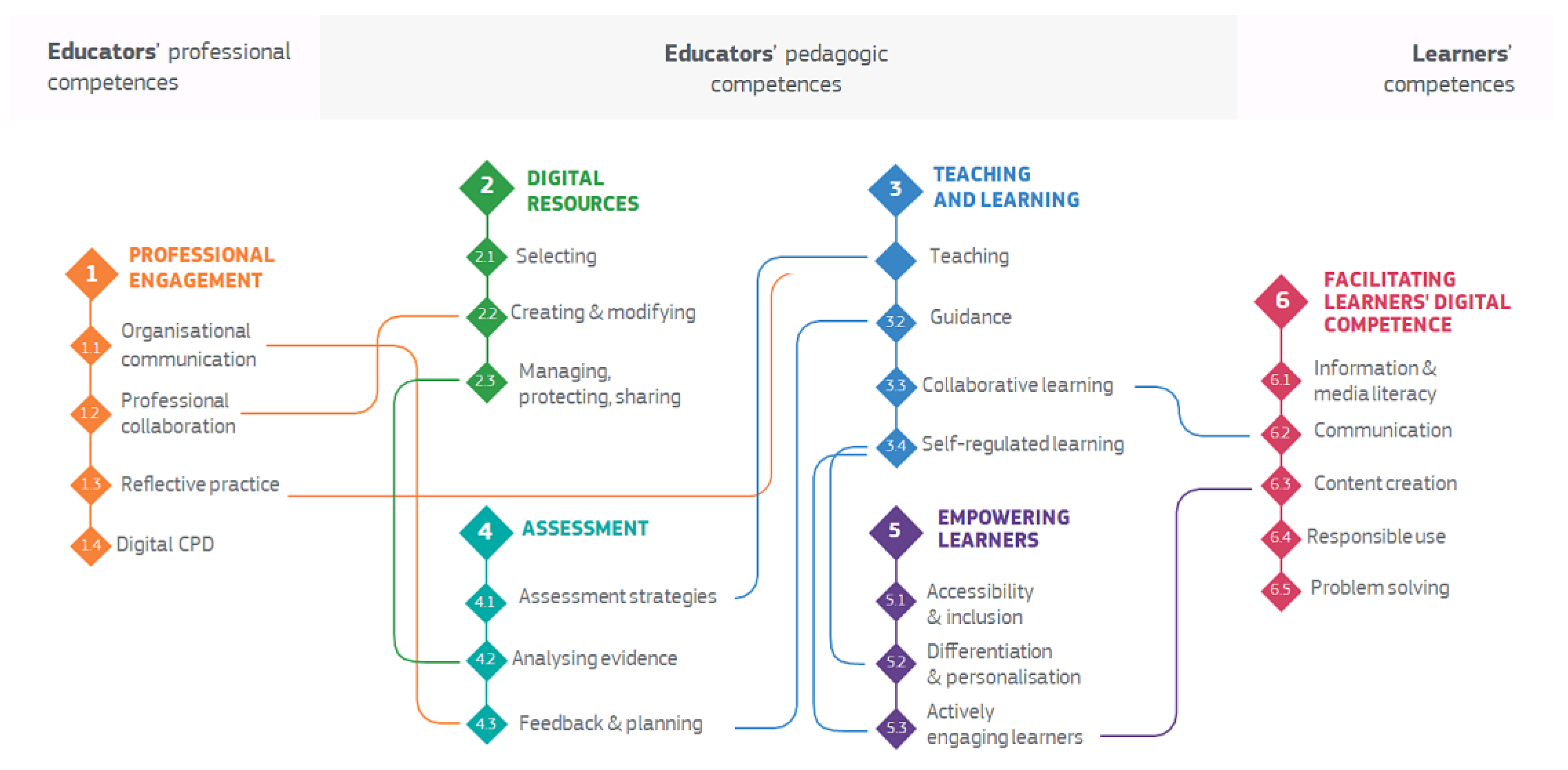

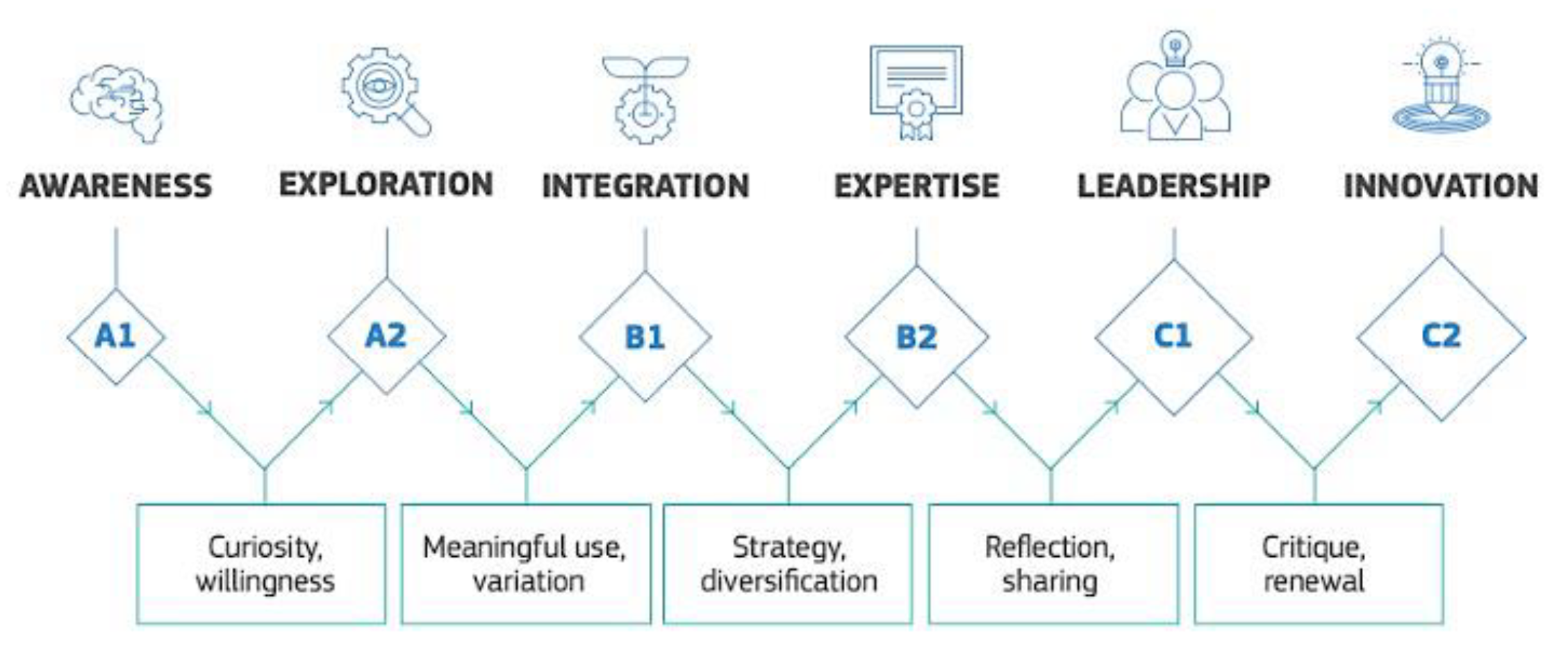

2.1. Digital Competence Benchmarks for Teachers

2.2. Teachers’ Digital Competences According to DigCompEdu

3. Materials and Methods

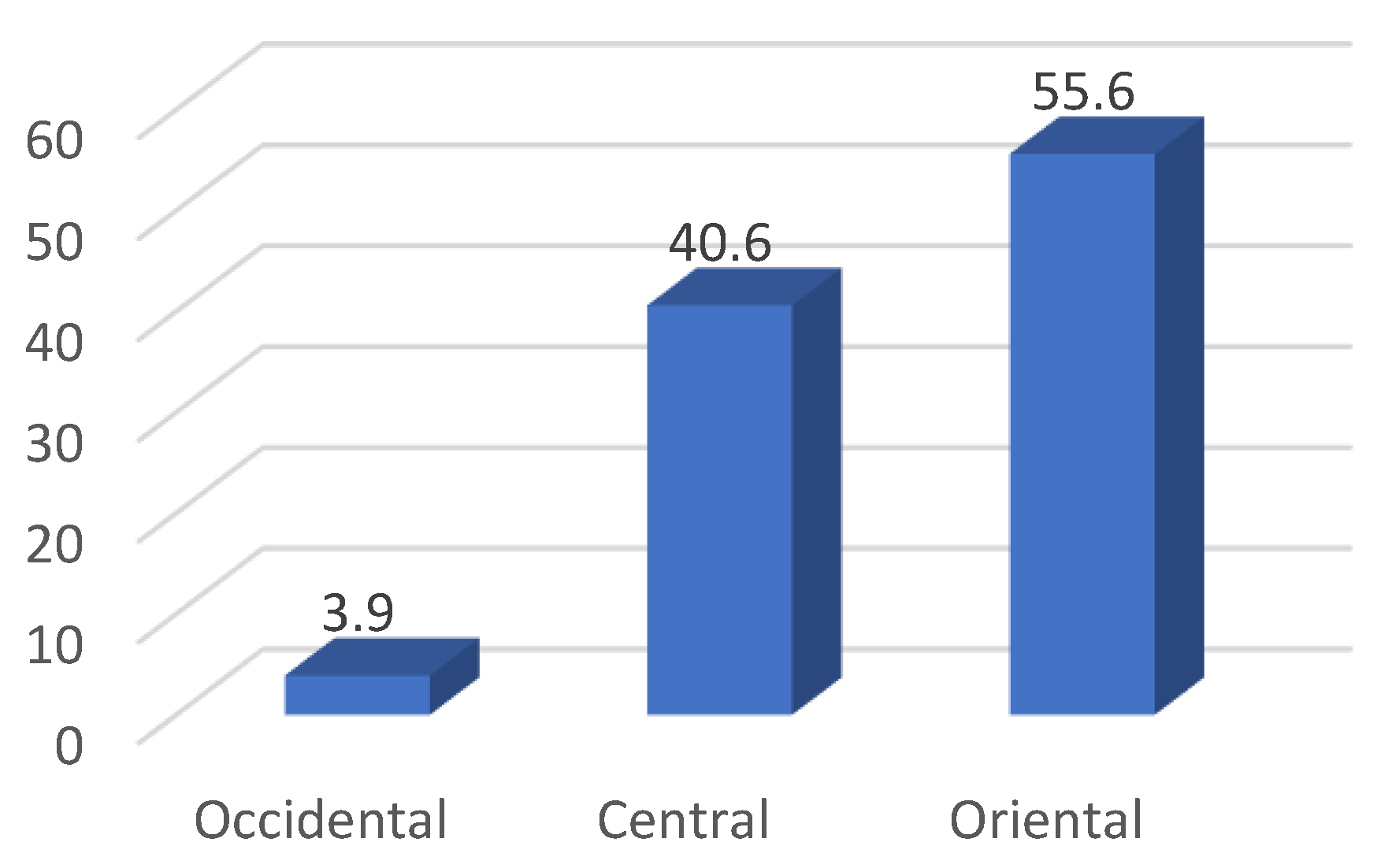

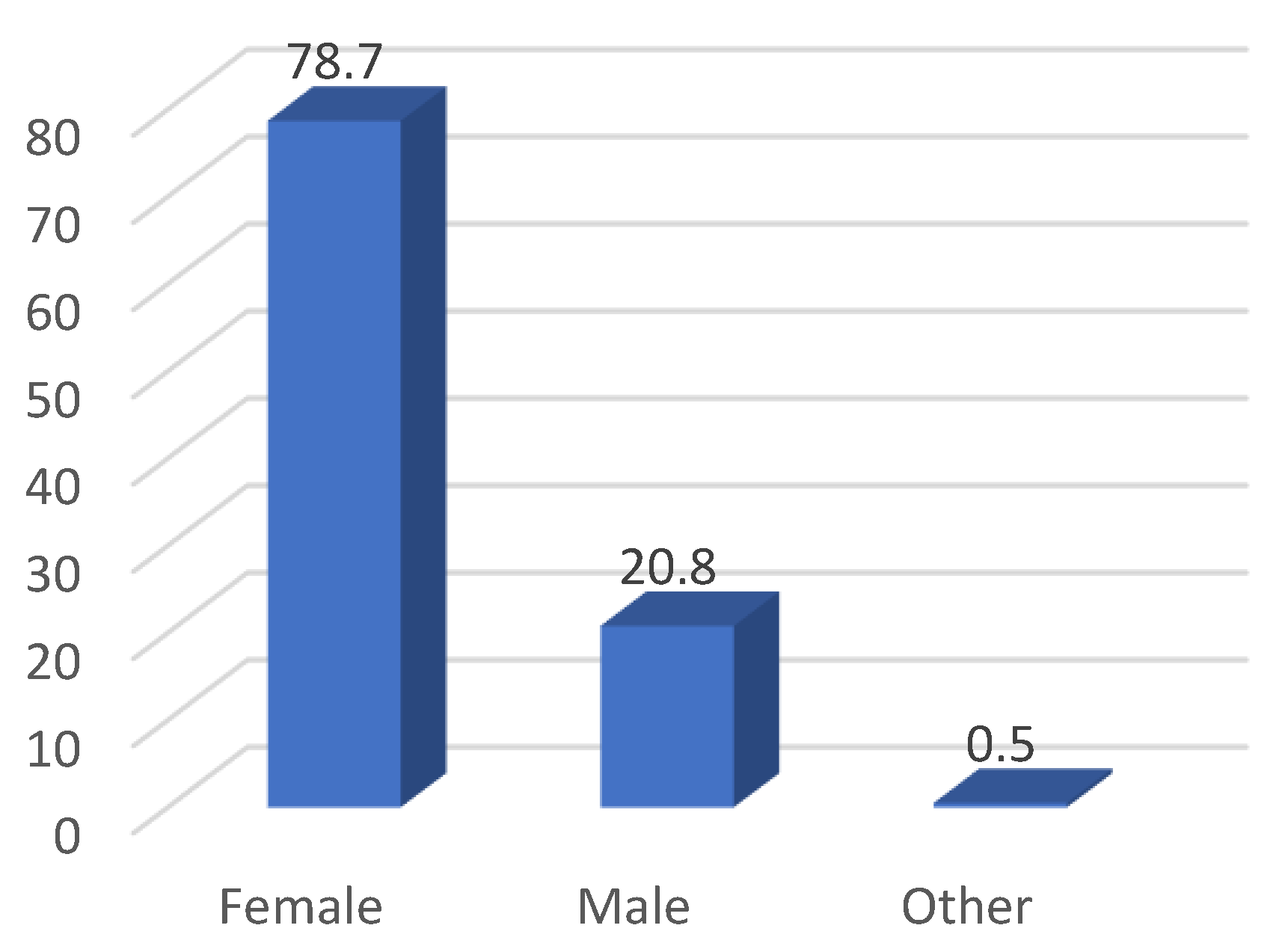

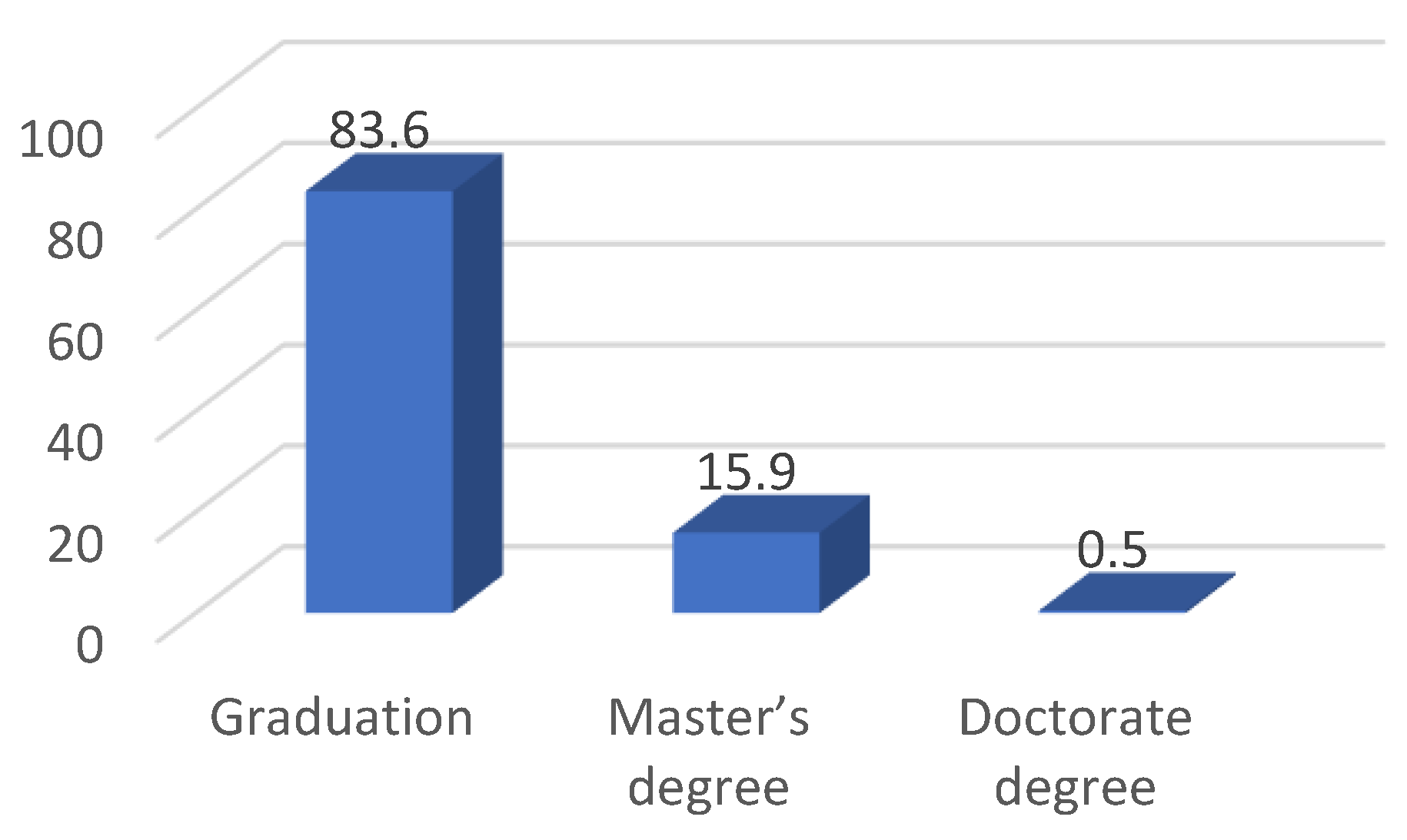

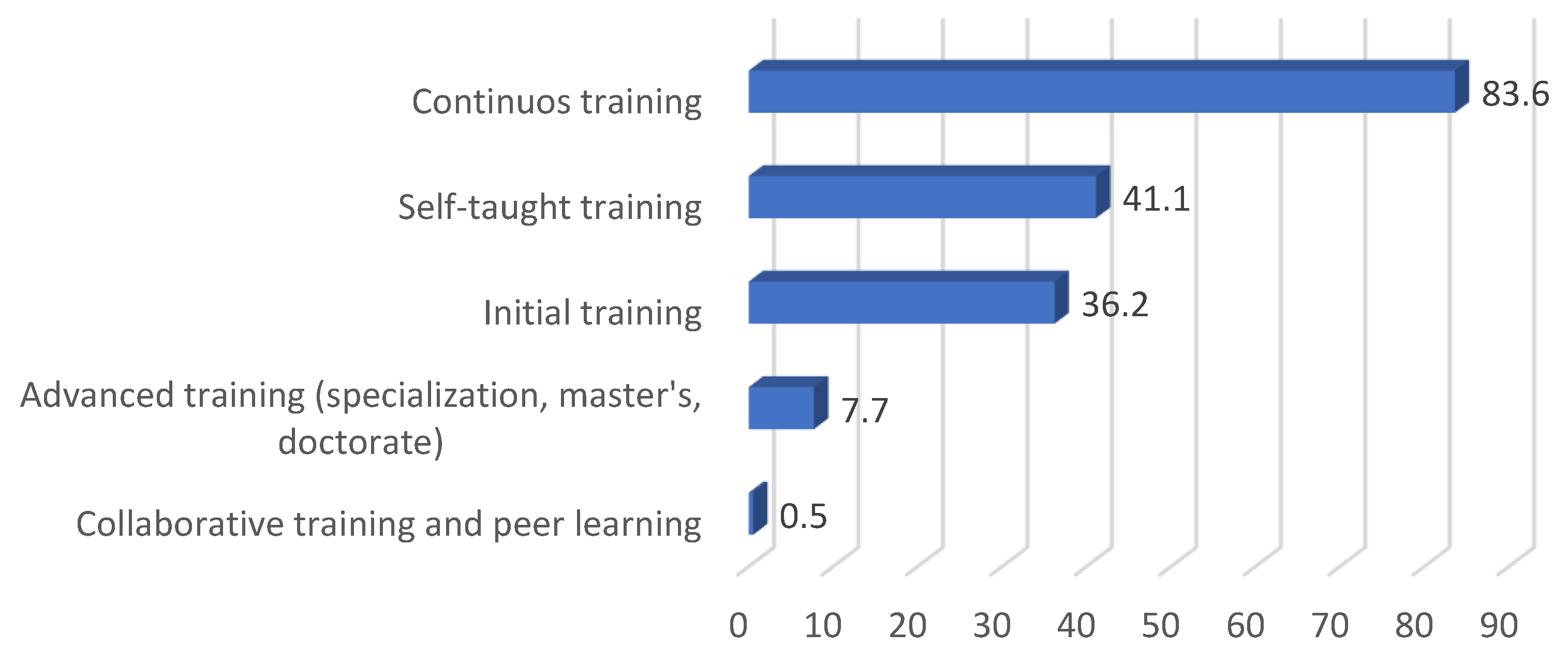

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instrument

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis Procedures

4. Presentation and Analysis of Results

4.1. Category (i) Selecting

4.2. Category (ii) Creating and Modifying

4.3. Category (iii) Managing, Protecting, and Sharing Digital Resources

4.4. Global Analysis

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- OECD. PISA 2018 Results (Volume VI). Are Students Ready to Thrive in an Interconnected World? PISA, OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture. Key Competences for Lifelong Learning; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2019; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/569540 (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Loureiro, A.C.; Osório, A.J.; Meirinhos, M. Competência Digital: Um estudo sobre as competências dos professores para a integração das TIC em contextos educativos [Digital Competence: A study on teachers’ competences for integrating ICT in educational contexts]. In Atas Book of the Challenges 2021: Desafios do Digital [Book of the Challenges 2021: Digital Challenges]; Universidade do Minho: Braga, Portugal, 2021; pp. 457–465. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1822/77709 (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Redecker, C. European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators: DigCompEdu; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2017; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/159770 (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- UNESCO. ICT Competency Framework for Teachers. Unesco Digital Library, 2018. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000265721 (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- ISTE Standards. International Society for Technology in Education. Available online: https://cdn.iste.org/iste-standards (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- INTEF. Common Digital Competence Framework for Teachers. Available online: https://aprende.intef.es/sites/default/files/2018-05/2017_1024-Common-Digital-Competence-Framework-For-Teachers.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Meirinhos, M.; Osório, A.J. Referenciais de competências digitais para a formação de professores [Digital competence benchmarks for teacher training]. In Atas Book of the Challenges 2019: Desafios da Inteligência Artificial na Educação [Book of the Challenges 2019: Challenges of Artificial Intelligence in Education]; Universidade do Minho: Braga, Portugal, 2019; pp. 1001–1016. Available online: https://www.nonio.uminho.pt/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/atas_ch2019_full.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Loureiro, A.C.; Meirinhos, M.; Osório, A.J. Competence Development for the Educational Integration of Digital Resources. In Proceedings of the EDULEARN21 Proceedings, 13th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, Online, 5–6 July 2021; pp. 11287–11296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presidência do Conselho de Ministros. Resolução do Conselho de Ministros n.o 30/2020. Plano de Ação para a Transição Digital [Council of Ministers Resolution 30/2020. Digital Transition Action Plan]. Diário da República, 20 April 2020. pp. 6–32. Available online: https://files.dre.pt/1s/2020/04/07800/0000600032.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Al Shabibi, A.; Al Shabibi, T. Teachers’ Training Needs for Digital Competences. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Arab Conference on Information Technology (ACIT), Muscat, Oma, 21–23 December 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Trindade, S.; Gomes Ferreira, A. Competências digitais docentes: O DigCompEdu CheckIn como processo de evolução da literacia para a fluência digital [Teachers’ digital competences: DigCompEdu CheckIn as a process of moving from literacy to digital fluency]. Icono 2020, 18, 162–187. Available online: https://icono14.net/ojs/index.php/icono14/article/download/1519/1704?inline=1 (accessed on 2 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Momdjian, L.; Manegre, M.; Gutiérrez-Colón, M. Digital competences of teachers in Lebanon: A comparison of teachers’ competences to educational standards. Res. Learn. Technol. 2024, 32, 3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelova, V.; Nikolova, A. The Digital Competence of Students Preparing to become Primary School Teachers—Perspectives for Development. TEM J. 2024, 13, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, V.G.; Tort, E.G.; Rodríguez, M.d.L.F.; Laverde, A.C. El profesorado de Educación Infantil y Primaria: Formación tecnológica y competencia digital [Pre-school and primary school teachers: Technological training and digital competence]. Innoeduca. Int. J. Technol. Educ. Innov. 2021, 7, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarr, O. Exploring and reflecting on the influences that shape teacher professional digital competence frameworks. Teach. Teach. 2024, 30, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andaluz-Delgado, S.; Ordoñez-Olmedo, E.; Gutiérrez-Martín, N. Assessment of Digital Teaching Competence in Non-University Education. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosseck, G.; Bran, R.A.; Tîru, L.G. Digital Assessment: A Survey of Romanian Higher Education Teachers’ Practices and Needs. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, V.M.; Méndez, V.G.; Chacón, J.P. Formación y competencia digital del profesorado de Educación Secundaria en España [Training and digital competence of secondary education teachers in Spain]. Texto Livre 2023, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerhofer-Parra, R.; González-Martínez, J. Percepciones docentes sobre las competencias digitales y su uso para el bienestar digital: Un análisis mixto sobre la ampliación del marco DigCompEdu [Teachers’ perceptions of digital competences and their use for digital well-being: A mixed analysis of the expansion of the DigCompEdu framework]. Edutec Rev. Electrónica Tecnol. Educ. 2024, 87, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Rodríguez, A.; Guillén-Gámez, F.D.; Cabero Almenara, J.; Gutiérrez-Castillo, J.J. Teacher Digital Competence in the education levels of Compulsory Education according to DigCompEdu: The impact of demographic predictors on its development. Interact. Des. Archit. J. 2023, 57, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fissore, C.; Floris, F.; Marchisio, M.; Rabellino, S.; Sacchet, M. Digital Competences for Educators in the Italian Secondary School: A comparison between DigCompEdu reference framework and the pp&s project experience. International Association for Development of the Information Society. Presented at the International Association for Development of the Information Society (IADIS), International Conference on e-Learning, Virtual, 21–23 July 2020. pp. 47–54. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED621788.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Benali, M.; Mak, J. A comparative analysis of international frameworks for Teachers’ Digital Competences. Int. J. Educ. Dev. Using Inf. Commun. Technol. 2022, 18, 122–138. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1377714 (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y. International Research Hotspots of Teachers’ Digital Literacy/Competence. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference of Educational Innovation Through Technology (EITT), Fuzhou, China, 15–17 December 2023; pp. 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekerle, C.; Daumiller, M.; Kollar, I. Using digital technology to promote higher education learning: The importance of different learning activities and their relations to learning outcomes. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2022, 54, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, A.C.; Meirinhos, M.; Osório, J.A. Competência Digital Docente: Linhas de orientação dos referenciais [Digital Teaching Competence: Guidelines for referential]. Texto Livre Ling. Tecnol. 2020, 13, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Research Centre, Institute for Prospective Technological Studies; Punie, Y.; Ferrari, A.; Brečko, B. DIGCOMP: A Framework for Developing and Understanding Digital Competence in Europe; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2013; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2788/52966 (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Bekiaridis, G.; Attwell, G. Supplement to the DigCompEDU Framework, 2024. Available online: https://aipioneers.org/supplement-to-the-digcompedu-framework/ (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Verdú-Pina, M.; Usart, M.; Grimalt-Álvaro, C.; Ortega-Torres, E. La competencia digital de alumnos y profesores en una red valenciana de escuelas cooperativas [Students’ and teachers’ digital competence in a Valencian network of cooperative schools]. Aloma Rev. Psicol. Ciències l’Eduació l’Esport 2023, 41, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, D. Science teachers’ conceptions of teaching and learning, ICT efficacy, ICT professional development and ICT practices enacted in their classrooms. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 73, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, L.; Esteve, F.; Adell, J. ¿Por qué es necesario repensar la competencia docente para el mundo digital? [Why is it necessary to rethink teaching competence for the digital world?]. RED-Rev. Educ. A Distancia 2018, 56, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lores Gómez, B.; Sánchez Thevenet, P.; García Bellido, M.R. La formación de la competencia digital en los docentes [Digital competence training of teachers]. Profr. Rev. Currículum Form. Profr. 2019, 23, 234–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Education Area. Digital Education Action Plan. 2020. Available online: https://education.ec.europa.eu/focus-topics/digital-education/action-plan (accessed on 6 February 2024).

| Age | N = 207 | % |

|---|---|---|

| less than 31 years | 6 | 2.9 |

| 31–40 years | 12 | 5.8 |

| 41–50 years | 104 | 50.2 |

| 51–60 years | 80 | 38.6 |

| over 60 years | 5 | 2.4 |

| Years of Active Teaching | N = 207 | % |

|---|---|---|

| less than 11 years | 28 | 13.5 |

| 11–20 years | 47 | 22.7 |

| 21–30 years | 88 | 42.5 |

| 31–40 years | 42 | 20.3 |

| over 40 years | 2 | 1 |

| Educational Stage | N = 207 | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1st Cycle | 72 | 34.8 |

| 2nd Cycle | 40 | 19.3 |

| 3rd Cycle | 87 | 42.0 |

| 1st and 2nd Cycles | 2 | 1.0 |

| 2nd and 3rd Cycles | 6 | 2.9 |

| Specialization in Digital Technologies and Education (Level) | N = 207 | % |

|---|---|---|

| specialization/graduate | 13 | 6.2 |

| master’s degree | 1 | 0.5 |

| doctorate | 0 | 0 |

| continuous training | 105 | 50.7 |

| none | 88 | 42.5 |

| Hours of Training in the Last 10 Years | N = 207 | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 33 | 15.9 |

| less than 51 | 96 | 46.4 |

| from 51 to 100 | 44 | 21.3 |

| from 101 to 150 | 14 | 6.8 |

| from 151 to 200 | 8 | 3.8 |

| from 201 to 250 | 6 | 2.9 |

| over 250 | 6 | 2.9 |

| Competence | (i) Select | (ii) Create and Modify | (iii) Share Digital Resources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of descriptors (questions) | 14 | 8 | 7 |

| Objectives | (i) identify, select, and effectively evaluate the resources best suited to their learning objectives and methodological approach | (ii) modify, add, and develop digital resources to support their practice | (iii) be aware of how to use and manage digital content responsibly |

| Descriptor/Question | Scale 1–6 (1 = Never Use/Do; 6 = Always Use/Do) Level A1 to C2 N = 207 (100%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (A1) | 2 (A2) | 3 (B1) | 4 (B2) | 5 (C1) | 6 (C2) | |

| 2.1. I rarely use the internet to find resources for teaching and learning | 25 (12.1) | 12 (5.8) | 24 (11.6) | 21 (10.1) | 48 (23.2) | 77 (37.2) |

| 2.2. I use simple internet search strategies to identify digital content relevant to teaching and learning. | 2 (1.0) | 9 (4.3) | 29 (14.0) | 32 (15.5) | 60 (29.0) | 75 (36.2) |

| 2.3. I use educational platforms that provide digital resources. | 2 (1.0) | 12 (5.8) | 27 (13.0) | 27 (13.0) | 48 (23.2) | 91 (44.0) |

| 2.4. I adapt my research strategies based on the results I get. | 1 (0.5) | 9 (4.3) | 28 (13.5) | 46 (22.2) | 55 (26.6) | 68 (32.9) |

| 2.5. Filter the results obtained to find resources appropriate to my goals. | 0 (0.0) | 11 (5.3) | 21 (10.1) | 31 (15.0) | 61 (29.5) | 83 (40.1) |

| 2.6. I evaluate the quality of digital resources based on criteria such as place of publication, authorship, comments from other users. | 4 (1.9) | 17 (8.2) | 24 (11.6) | 34 (16.4) | 50 (24.2) | 78 (37.7) |

| 2.7. I select resources that my students may find interesting, such as videos. | 1 (0.5) | 8 (3.9) | 13 (6.3) | 23 (11.1) | 64 (30.9) | 98 (47.3) |

| 2.8. I combine my research strategies to identify resources that I can modify and adapt. Example: Search and filter by license, file type, date, user comments, etc. | 10 (4.8) | 26 (12.6) | 32 (15.5) | 34 (16.4) | 57 (27.5) | 48 (23.2) |

| 2.9. I value the reliability of digital resources, their suitability for my group of students and the specific learning objective. | 2 (1.0) | 6 (2.9) | 17 (8.2) | 26 (12.6) | 57 (27.5) | 99 (47.8) |

| 2.10. I evaluate and make recommendations on the resources I use. | 13 (6.3) | 30 (14.5) | 29 14.0) | 50 (24.2) | 46 (22.2) | 39 (18.8) |

| 2.11. I use a variety of internet search sources. Example: collaborative platforms, digital resource repositories, etc. | 8 (3.9) | 22 (10.6) | 21 (10.1) | 40 (19.3) | 65 (31.4) | 51 (24.6) |

| 2.12. When I use the resources in the classes, I explain their origin and refer to any biases. | 18 (8.7) | 36 (17.4) | 36 (17.4) | 34 (16.4) | 41 (19.8) | 42 (20.3) |

| 2.13. I advise colleagues on internet research strategies, repositories, and resources appropriate to education. | 28 (13.5) | 37 (17.9) | 48 (23.2) | 44 (21.3) | 38 (18.4) | 12 (5.8) |

| 2.14. I organize my own repository of links to resources, duly annotated and classified, and share it with other colleagues. | 35 (16.9) | 44 (21.3) | 38 (18.4) | 38 (18.4) | 29 (14.0) | 23 (11.1) |

| Percentage of the weighted average according to competence levels | 13.2 | 5.2 | 11.1 | 10.2 | 23.1 | 37.2 |

| Descriptor/Question | Scale 1–6 (1 = Never Use/Do; 6 = Always Use/Do) Level A1 to C2 N = 207 (100%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (A1) | 2 (A2) | 3 (B1) | 4 (B2) | 5 (C1) | 6 (C2) | |

| 3.1. I use digital resources, but I do not modify them or create my own resources | 35 (16.9) | 50 (22.4) | 53 (25.6) | 36 (17.4) | 25 (12.1) | 8 (3.9) |

| 3.2. I use a software editor to create and modify content. Example: worksheets, proofs, presentations, spreadsheets. | 7 (3.4) | 15 (7.2) | 41 (19.8) | 34 (16.4) | 62 (30.0) | 48 (23.2) |

| 3.3. I create simple digital resources (e.g., presentations). | 10 (4.8) | 14 (6.8) | 27 (13.0) | 47 (22.7) | 62 (30.0) | 47 (22.7) |

| 3.4. I create digital resources (example: presentations) and integrate animations, links, multimedia and interactive elements. | 16 (7.7) | 27 (13.0) | 44 (21.3) | 40 (19.3) | 46 (22.2) | 34 (16.4) |

| 3.5. I make modifications to the digital learning resources I use to suit them to learning objectives. | 6 (2.9) | 12 (5.8) | 34 (16.4) | 48 (23.2) | 53 (25.6) | 54 (26.1) |

| 3.6. I create digital, complex and interactive learning activities, for example: online assessments (quizzes, forms, etc.), online collaborative learning activities (wikis, blogs), games and applications. | 43 (20.8) | 44 (21.3) | 36 (17.4) | 34 (16.4) | 30 (14.5) | 20 (9.7) |

| Percentage of the weighted average according to competence levels | 17.0 | 24.2 | 25.6 | 17.4 | 12.0 | 3.8 |

| Descriptor/Question | Scale 1–6 (1 = Never Use/Do; 6 = Always Use/Do) Level A1 to C2 N = 207 (100%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (A1) | 2 (A2) | 3 (B1) | 4 (B2) | 5 (C1) | 6 (C2) | |

| 4.1. Store and organize digital resources for my future use. | 2 (1.0) | 16 (7.7) | 32 (15.5) | 24 (11.6) | 56 (27.1) | 77 (37.2) |

| 4.2. I share educational content by sending attachments in an email or through links. | 18 (8.7) | 15 (7.2) | 36 (17.4) | 38 (18.4) | 55 (26.6) | 45 (21.7) |

| 4.3. I share educational content by linking or incorporating it into virtual learning environments, e.g., on a website or blog, staff or educational institution. | 73 (35.3) | 39 (18.8) | 25 (12.1) | 29 (14.0) | 27 (13.0) | 14 (6.8) |

| 4.4. I am aware that some resources distributed on the Internet are protected by copyright. | 1 (0.5) | 6 (2.9) | 15 (7.2) | 16 (7.7) | 36 (17.4) | 133 (64.3) |

| 4.5. I protect access to private content, e.g., exams, student reports. | 18 (8.7) | 19 (9.2) | 34 (16.4) | 10 (4.8) | 29 (14.0) | 97 (46.9) |

| 4.6. I compile comprehensive repositories of digital content and make them available to students or other educators by applying their licenses to resources. | 75 (36.2) | 40 (19.3) | 32 (15.5) | 18 (8.7) | 27 (13.0) | 15 (7.2) |

| 4.7. I keep the resources that I share digitally and allow others to comment on, classify and modify them. | 73 (35.3) | 36 (17.4) | 43 (20.8) | 19 (9.2) | 18 (8.7) | 18 (8.7) |

| Percentage of the weighted average according to competence levels | 1.1 | 7.7 | 15.4 | 11.6 | 27.0 | 37.2 |

| Competence | Teacher Self-Assessment % | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| (i) Select Have the competence to effectively identify, select, and evaluate the resources best suited to the learning objectives and methodological approach. | 13.2 | 5.2 | 11.1 | 10.2 | 23.1 | 37.2 |

| (ii) Create and modify Have the competence to modify, add, and develop digital resources to support teaching practice. | 17.0 | 24.2 | 25.6 | 17.4 | 12.0 | 3.8 |

| (iii) Managing, protecting, and sharing digital resources Be aware of how to use and manage digital content responsibly. | 1.1 | 7.7 | 15.4 | 11.6 | 27.0 | 37.2 |

| Total | 31.3 | 37.1 | 52.1 | 39.2 | 62.1 | 78.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loureiro, A.C.; Santos, A.I.; Meirinhos, M. Digital Competence for Pedagogical Integration: A Study with Elementary School Teachers in the Azores. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14121293

Loureiro AC, Santos AI, Meirinhos M. Digital Competence for Pedagogical Integration: A Study with Elementary School Teachers in the Azores. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(12):1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14121293

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoureiro, Ana Claudia, Ana Isabel Santos, and Manuel Meirinhos. 2024. "Digital Competence for Pedagogical Integration: A Study with Elementary School Teachers in the Azores" Education Sciences 14, no. 12: 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14121293

APA StyleLoureiro, A. C., Santos, A. I., & Meirinhos, M. (2024). Digital Competence for Pedagogical Integration: A Study with Elementary School Teachers in the Azores. Education Sciences, 14(12), 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14121293