1. Introduction

Complementary to the diversified research on formal education, there is a growing body of research that studies structures and practises of the private tutoring industry. In the literature, these forms of supplementary education are also known as private supplementary tutoring (PST) or “shadow education” [

1] and have been proven as a global phenomenon [

2]. Shadow education is commonly defined as commercially provided learning activities in academic subjects delivered outside school hours offering educational services for students to better perform at school and/or increase their chances of passing high-stakes exams [

1,

3]. Therefore, PST is closely related to public schools and often mirrors core elements, such as the curriculum or ways of teaching [

1,

3,

4,

5]. However, Gupta [

6] points out that “‘shadowing’ is not a neutral process, it is executed tactically and strategically with an aim to provide private tutoring a valued, legitimised, and competitive space” [

6] (p. 394). Educational scientists also elaborated on how the national and regional particularities of PST programmes vary in different geographical contexts (see, e.g., [

6,

7,

8,

9]). Other researchers revealed that a critique of formal schooling often serves to emphasise the need to provide PST (e.g., [

10,

11]).

It has also been shown that especially in competitive education systems and at selective transitions, PST is particularly popular, as parents often understand private tutoring as a strategy to support their child’s school success (e.g., [

5,

12,

13,

14]). Closely related to this is the criticism of PST that it exacerbates social inequalities, because socio-economically privileged families can more easily afford the costs of PST than less privileged families [

4,

5,

15,

16].

This paper connects to the international debates concerning the complex entanglements between public education and supplementary education. By using a case study from Zurich (Switzerland), our study focuses on a particular segment of the supplementary education market, namely preparation courses that promise to professionally prepare students for the transition to the most academically challenging secondary school track. This school track, called

Gymnasium, is attractive for students because its graduates are the only ones that are entitled direct access to university education. However, to be admitted to

Gymnasium in the first place, students are required to have good marks and pass a highly selective standardised central entrance examination (CEE). It has been argued elsewhere that this highly restrictive entrance policy of

Gymnasium feeds a private education market offering CEE preparation programmes to students [

17]. For these educational entrepreneurs, the term “edupreneurs” has also been established in the relevant literature to mark the increasing application of economic logics enacted by headmasters, private tutors, or companies marketing PST and/or learning technologies [

18,

19].

The purpose of this paper is to analyse a particular facet of the marketing strategies of edupreneurs who offer a range of CEE preparation programmes via their homepages. Established definitions of the term “marketing strategies” in the academic literature normally refer to patterns of decision-making that frame crucial organisational choices about its products, markets, marketing activities, and the resources available for marketing. The aim of such strategies is to enable an organisation to create, communicate, and deliver products that provide value to customers [

20,

21]. Entrepreneurs offering the services of private higher education institutions, for example, apply as elements of such marketing strategies “strategic location, quality of the offered products, attractive promotions, competitive prices, professional and human resources, effective and efficient processes, elegant organizational performance” [

22] (p. 107). Marketing strategies encompass a complex combination of market analysis, product development, business decisions, and targeted promotion and advertisement. It is important, therefore, to point out that this paper focuses on a particular aspect of edupreneurs’ marketing strategies. Accordingly, the research question of this paper is as follows: how do edupreneurs promote their services on their websites to families with children who prepare for the CEE?

In the remainder of the paper, we discuss the relevant literature on PST, using a website analysis of edupreneurs and “geographies of marketization” as our conceptual approach (

Section 2). We next describe the educational landscape in the canton of Zurich (

Section 3). Then, we explain the methodological approach of our study (

Section 4). In

Section 5, we present two main findings. First, we elucidate that private CEE preparation courses in Zurich are advertised as a market solution that compensates for what public schools do not adequately offer, but which is required by the most demanding school track within the education system. Second, we show how edupreneurs’ websites use rational and emotional arguments to convince parents of the normality of and need for courses for their

Gymnasium-aspiring children. In the concluding discussion (

Section 6), we summarise how the findings relate back to our conceptual approach, complement existing debates within the PST literature, and why we would argue that selective educational transitions have much wider relevance for educational policy and society here and elsewhere.

2. Edupreneurs’ Marketization of PST

The aim of PST is to help pupils perform better at school. The tutoring programmes generally attempt to fill knowledge gaps and have positive effects on the students’ academic performance. Other programmes are installed for more specific outcomes, such as passing high-stakes entrance tests or final examinations [

1,

4,

23]. The offered programmes show a wide range of variation, from one-to-one tutoring to private tuition in small or large groups to distance learning courses [

8].

The demand for PST is repeatedly framed as arising from increasingly competitive and selective education systems and national education policies that hold parents responsible for the success of their children’s educational careers [

23]. In such contexts, being involved in children’s education is increasingly seen as a practise of good parenting [

24,

25]. This is also reflected in parental practises of purchasing and choosing appropriate supplementary learning activities for one’s child (e.g., [

5,

13,

23]). Indeed, many parents and children consider the academic inputs provided by PST as an essential resource for success in their selective education system [

5,

8]. Therefore, purchasing PST is not only understood to be support for weaker students but especially as support for good students who wish to prepare for competitive and high-stakes assessments. These students are eager to win the competition for one of the limited school places in academically selective schools [

5,

23,

26,

27]. Holloway et al. point out that parents in neighbourhoods where the use of PST is high “are repeatedly exposed to tuition through parenting networks, children’s peer groups, local advertising and high-street tuition businesses, and these encounters can ensure tuition emerges in the locality as an unremarkable, everyday practice” [

23] (p. 7). This “normalisation” [

23] (p. 7) of the use of PST, they argue, leads other parents to also use tutoring, as they do not want to be the ones who withhold something from their child and disadvantage them in this way. Phillippo et al. [

27], using data from Chicago, demonstrate that children from wealthy families take it for granted that they will receive PST to prepare for high-stakes exams. At the same time, however, children from working-class families are often unaware that such services even exist [

27]. For these reasons and, in particular, because socioeconomically privileged families can more easily afford the costs of PST compared to less privileged families [

5,

16], it is argued that PST can undermine “the meritocratic logic and equity principles of education systems” [

28] (p. 553) and exacerbate social inequalities. Drawing on data from Australia, Doherty and Dooley [

28] refer to the purchase of PST as an “insurance strategy” by parents to secure academic status in a competitive education system (see also [

13,

29,

30]). The mentioned parental practises are in certain social and cultural contexts combined with a loss of trust in public education by parents or result in students prioritising private tutoring to school [

5,

14,

15,

31]. These and other arguments are used to explain the growth of the PST market (see [

1,

3]).

Scholars with a particular interest in the supply side draw on websites as rich and accessible databases to analyse edupreneurs’ marketing strategies [

29]. Kozar, for example, argues that websites are used by educational institutions and PST entrepreneurs as a strategic tool “for positioning and differentiating themselves on the educational market, building legitimacy and attracting students” [

29] (p. 357). Yung and Yuan [

32], focusing on the self-presentation of English language tutors in Hong Kong on websites, observe that due to the commercial nature of shadow education, the analysis of these websites “can reflect the specific social expectations associated with shadow education” [

32] (p. 155). Chang, who examines the self-presentations of after-school programmes offering supplementary English education in Taiwan, goes further. He argues that the “multiple self-presentations” only gain credibility through the interplay of multiple social discourses, such as discourses about the role of English in Taiwanese society, teaching methods, and mainstream education [

33]. The reason why Chang, Kozar, Yung and Yoan, along with other researchers primarily chose the websites of various educational institutions and PST entrepreneurs as their data corpora is that it may be very challenging to access data on shadow education in particular geographical and social contexts. Websites not only provide a rich and accessible data corpus but also encapsulate a wide range of actors, voices, and narratives from which wider conclusions can be drawn in terms of the interrelation of public and shadow education, the general acceptance of PST in society, or the economic significance of the PST industry in a particular geographical context.

Various studies have shown that educational reforms, political decisions about PST funding and school regulations in general, parental trust in mainstream education, and the extent of academic competition in an education system can influence the acceptance of PST [

13,

28,

33,

34,

35]. Doherty and Dooley [

28] explain that the social acceptance of PST in Australia has changed over time. They illustrate how this process has involved both clever marketing by the PST industry and legitimising narratives in school newsletters that present PST is an ally of schools.

In Switzerland, very little research has examined private CEE preparation courses in particular or private supplementary tutoring (PST) in general. However, we know from international comparative studies based on PISA data that Switzerland is one of the countries in which the proportion of students taking part in PST is significantly below average [

36]. And the quantitative studies by Moser et al. [

12] and Hof and Wolter [

37] indicate that children from socioeconomically privileged families make greater use of PST, especially before educational transitions. As a matter of fact, there are neither official data nor estimates available on the number, scale, or growth of CEE preparation course providers in Switzerland or Zurich, respectively. For Zurich, Moser at al. [

12] have shown that it is students from upper- and middle-class families with good and very good school marks who are most likely to attend costly private preparation courses for the CEE, which in fact further increase their chances of passing the CEE [

12].

In line with international research on PST discussed above, we also consider private providers’ websites as more than sources of information for parents about possible services. The presentations on the websites should be taken as temporary snapshots of market actors in Zurich and elsewhere, which are subject to permanent adaptation and re-creation. Following our understanding of websites as complex agents of edupreneurs’ market activities, we suggest that a performative understanding of markets is most appropriate. Therefore, we are conceptually inspired by “geographies of marketization” [

38,

39], which promote replacing the rather static idea of “the” market as an entity with the more dynamic understanding of markets as forms of “incomplete and nonlinear” marketizations [

39] (p. 125). Studies on neoliberal school reforms in the U.S., for example, have used this approach to critically assess the entanglement of the private charter school market with the governance practises of public education representatives [

40] and the reciprocal influence of politicians, philanthropists, and corporations, as well as “non-elites”, such as parents and local communities [

41]. Theoretically, “geographies of marketization” draw on Michel Callon’s longstanding work on “markets in the making” [

42,

43]. We identify the strengths of the “geographies of marketization” approach not only in its account for the performativity of markets but also in its ability to capture the inconsistency of diverse actors, which are entangled in “struggles between antagonistic rationalities” [

39] (p. 131). These struggles are particularly interesting because they indicate opportunities for contestation and resistance to market activities and actors without drawing a sharp line between state and market [

17,

40,

41]. This is highly important for our study because we analyse the market niche of edupreneurs offering CEE preparation courses, which as a field sits at the interface between public and private education.

From the “geographies of marketization” debate, we choose the key terms “problematization” and “commodification” because they enable us to capture the performativity of this private educational market [

24,

25]. In a nutshell, problematization is the formulation of a problem and its subsequent translation into an economic opportunity. Problematization involves constructing a sharp line between the (problem-overdrawn) state and the (problem-solving) market, where the state vs. market binary is hard to uphold upon closer inspection. Problematization helps us to capture the arguments, rationalities, and inconsistencies with which the edupreneurs create their own market necessity. In other words, which arguments are used by the actors to explain the market niche or gap that they offer to fill? In our case study, we are interested in the ways that edupreneurs justify the need for CEE preparation courses. Commodification is the transformation of goods into tradable objects and services that are constructed by emphasis, e.g., particular qualities (see [

17] for a more detailed elaboration). Commodification puts a specific focus on the products and services of the edupreneurs, pointing out what customers receive when buying a certain product or service. We shed light on the features and qualities of the CEE preparation courses that are offered on the edupreneurs’ homepages.

In line with this approach, we understand educational markets as “contingent outcomes of the articulation of diverse market and non-market logics” [

39] (p. 133). We illustrate the complex entanglements of public and private spheres that are attached to edupreneurs’ marketing strategies of their CEE preparation courses. The two key terms, problematization and commodification, are used as conceptual entry points to elaborate a deeper understanding of our data set. However, problematization and commodification are closely entangled with each other, where problematization lays the foundation for commodification. Using both terms for our analysis provides insights into the diverse ways that products and services are promoted by edupreneurs to potential customers.

3. Educational Landscape in the Canton of Zurich

With the exception of the canton of Ticino, all cantons in Switzerland have early tracking systems with a selective transition from primary school to secondary school after grade 6, where students are placed on different secondary school tracks according to their academic ability. Since the governance of education is the responsibility of the 26 cantons, each cantonal department of education regulates school transitions autonomously. Consequently, the rules for the transition to

Gymnasium, the most academically demanding secondary school track, vary widely between the cantons. Where some rely on a recommendation report by teachers and/or school grades, others have strict entrance tests or use a combination of selection procedures (see [

44] for a comparative analysis of transition systems in different cantons and [

45,

46] for a particular focus on educational inequalities).

In the canton of Zurich, students can transfer to

Gymnasium either at the end of primary school in year 6 (long-term

Gymnasium) or after their second or third year in a lower-level secondary school track in year 8 or 9 (short-term

Gymnasium). The selection for

Gymnasium relies on school grades and the highly selective CEE. Each year, students with good and very good marks in years 6 and 8/9 enrol for the CEE in the canton of Zurich. In year 6, about 30 per cent of the year enrol for the test and in year 8, some 20 per cent, less so in year 9 [

41]. Even though most of the aspiring students taking the CEE each year are estimated to have undergone intensive preparation, about half of them fail the test, resulting in about 15 per cent in year 6 and less than 10 per cent both in years 8 and 9 [

47]. The intention of this entrance test is to select the most gifted students for

Gymnasium [

48].

It is clear to students and their parents that if they want to pass this formal assessment, they need to be well prepared. The demand for test preparation is met by a rich supply of CEE preparation courses [

17]. Over the years, a complex market has emerged with two main groups of stakeholders. One important group is the state-funded school, which offers CEE preparation courses free of charge. A second important group comprises edupreneurs, which offer CEE preparation courses varying from intensive study weeks during school holidays to 14-week courses covering all exam areas and costing several thousand euros [

49] (in addition to these two main actors, very few nonprofit initiatives offer intensive free CEE preparation for selected children from socially disadvantaged backgrounds (see [

50])). The courses offered by edupreneurs are not entirely uncontroversial in politics. Left-wing and centre parties argue that many families cannot afford such courses and that these courses therefore contribute to exacerbating social inequalities (e.g., [

51]).

Generally, after year 6, the vast majority of students does not attend

Gymnasium but a lower-level secondary school (years 7–9), which primarily prepares them for vocational education and training (VET). After VET, the educational pathway may be continued with vocational tertiary education or at a university of applied sciences [

52]. For this reason and relating to the national level, the proportion of young adults (25–34 years) with tertiary education (52%) is slightly above the OECD average of 47% [

53], although only a minority of all students attend

Gymnasium.

4. Compiling and Analysing the Data

The data corpus consists of the websites of 34 edupreneurs offering CEE preparation courses in Zurich. To compile our corpus, we first performed a systematic search on

www.google.com URL access on 9 December 2021. This search consisted of the following German key words and combinations: “

Gymivorbereitungskurse (i.e., CEE preparation course) AND

Zürich”, “

Lernstudio (i.e., learning centre) AND

Zürich”, “

Gymnasium AND

Vorbereitungskurs AND

Zürich”, “

ZAP AND

Gymnasium AND

Kurs (i.e., course)” (

ZAP is the German equivalent of CEE). The top 50 search results were screened in detail. We identified 34 edupreneurs offering CEE preparation courses in small groups, some of which (14) also provided one-to-one tutoring to prepare for the CEE in the city of Zurich. Only one edupreneur offered the option of booking an online course. All of the edupreneurs had at least one location with rooms or a PST centre of their own in Zurich where the courses were taught in person. The majority of edupreneurs (31) provided all-year supplementary support for school subjects or professional language training and in addition to that, also offered CEE preparation courses. Only a minority of edupreneurs (3) specialised in CEE preparation courses only. According to the local commercial register, some of these edupreneurs were established at the end of the 1990s. Since 2010, newly founded suppliers have entered the market each year, though some of these may not have survived. Most websites provide some information on their teachers, ranging from single edupreneurs to companies with about 80 teachers. Of the 34 identified edupreneurs offering CEE preparation courses, we extracted all homepages and websites that were related to their CEE preparation offers in January 2022 and imported them into MAXQDA2020 in pdf format. In total, we extracted and analysed 166 webpages, all of which were in German. The 34 edupreneurs were anonymized by assigning them name codes from L1 to L34.

For the analysis of the extracted websites, we used a thematic analysis and its different phases [

54,

55]. Our guiding question was “How do the edupreneurs promote their services on their websites to families with children who prepare for the CEE?” and our analysis was conceptionally informed by the two key terms, problematization and commodification, derived from “geographies of marketization” (see

Section 2).

We used MAXQDA to organise the data corpus through initial coding. First, we divided the websites of the first ten edupreneurs between the two authors so that each author individually coded the websites of five edupreneurs, focusing on the way in which the CEE preparation courses were promoted. In doing so, we developed inductive codes (e.g., having fun at CEE-prep courses) and deductive codes (e.g., public school to not have enough time to prepare students for the CEE). After the initial coding of the first ten edupreneurs’ websites, we discussed all developed codes and combined these codes with further deductive codes derived from the relevant literature and agreed on a coding scheme. In the next step, we divided all the extracted webpages of the remaining 24 edupreneurs between the two authors. Both authors coded about half of the data accordingly. We also worked iteratively in this phase of initial coding so that the coded data were discussed several times between the two authors, new developed inductive codes were integrated, and previously coded data were recoded (total of 166 websites of the 34 edupreneurs). Subsequently, we generated initial themes. After some revisions of these initial themes (e.g., the initial theme “children need special support” was rejected as a separate theme and the associated codes were later attached to other sub-themes because as a theme, it was not clearly distinguishable from other themes and sub-themes), we identified two prominent themes that recur in edupreneurs’ website articulations. It is important to note that “themes are typically developed from multiple codes that identify different facets of the meaning focus of a theme” [

55] (p. 55). Our two dominant themes can be described as follows: in marketing their own courses, a reference to public education is established (theme 1, discussed in

Section 5.1) and the high quality of their services is emphasised (theme 2, discussed in

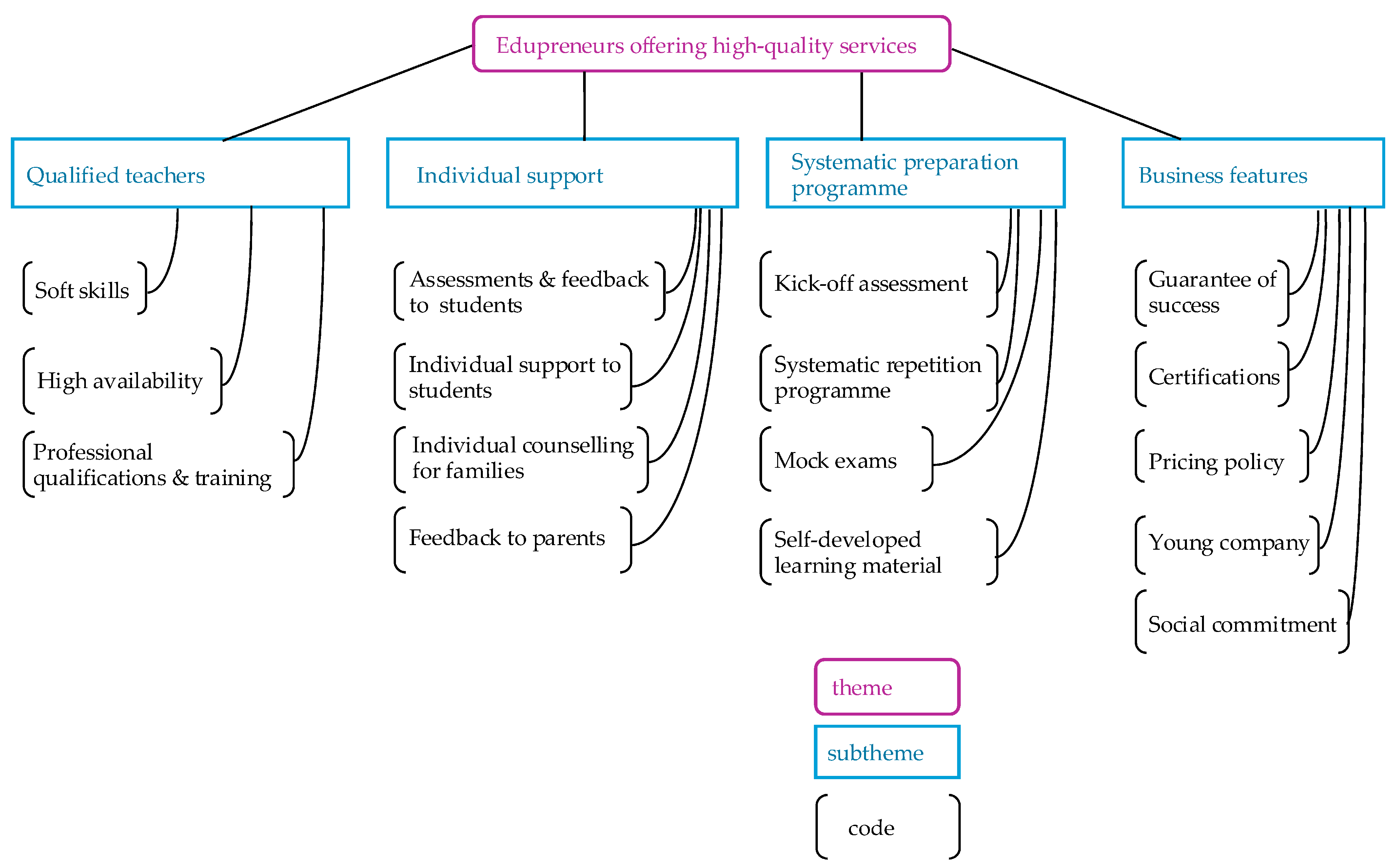

Section 5.2). The two themes are outlined in the following sections.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This study has examined the research question of how edupreneurs promote their services on their websites to families with children who prepare for the CEE. Methodically, we used a thematic analysis of the websites of private edupreneurs of CEE preparation programmes in Zurich. Drawing conceptually on “geographies of marketization”, the two key terms “problematization” and “commodification” guided the analysis of our data. Problematization helped us to elaborate on the arguments and (ir-)rationalities with which the edupreneurs highlight the gap and create a market niche for which they offer a solution (

Section 5.1). Closely entangled with problematization, commodification captures the features and qualities of the CEE preparation courses that the edupreneurs promoted on their homepages (

Section 5.2). We identify as the main result of our homepage analysis that public schools do not adequately equip students for passing the CEE and they need additional professional preparation, which is offered by edupreneurs.

In discussing our findings, we would like to offer three arguments that may advance the existing research on PST, edupreneurs, and selective school transitions. First, drawing on problematization, we illustrated how the edupreneurs identified a gap for which the public education system is responsible, and we elaborated on how they exploited this gap to market their courses. Our findings showed that edupreneurs’ marketing referred particularly to two sub-themes. One was the presentation of the CEE as a selective hurdle that had been installed by the public education system; the other one was that CEE preparation by public schools was insufficient. Educational researchers (e.g., [

13,

56]) argue that in education systems with high-stakes testing, parents try to overcome the tension between different schools’ levels of learning requirements by purchasing private tutoring. In short, parents are trying to compensate for an omission within the public education system by buying the services of edupreneurs. Our case study demonstrated that school access hurdles within the educational system provide a market niche for edupreneurs who offer commodified solutions to aspirational families. By emphasising the high selectivity of the CEE, the edupreneurs implicitly present the cantonal education system as responsible for the need for preparation courses in the first place. We could conclude that this would equip the edupreneurs with the argument that they cannot be held responsible for a thriving educational market that increases the advantages of the already privileged.

Second, the CEE preparation courses were promoted to high-performing students who tried to increase their chances for passing the CEE by booking a preparation course. In line with commodification, we showed how edupreneurs’ websites used rational and emotional arguments to convince parents of the need for courses for their aspirational children. Edupreneurs’ marketing strategies presented factual and rational appeals, such as outstanding teachers, individual learning opportunities, systematic preparation programmes, and institutional obstacles. In addition, many edupreneurs advertised that their teachers are empathetic, understanding, and patient coaches, thereby also capitalising on individualised emotional appeals for students. This argument adds a new aspect to existing research, which found “rational appeals” to be predominant within the PST market targeting high-stakes testing but “emotional appeals” to be widespread when addressing students with learning deficits [

10,

33,

56].

Third, the international literature is strong in analysing the general trends and local particularities of PST in the context of formal education. Some of these studies have emphasised that taking PST in addition to long school days burdens students and menaces their wellbeing (e.g., [

2,

13]). Our study contributes to this research by elaborating on students’ agency within comprehensive preparation programmes, which balance teaching for the test in small groups with offering individual support. Edupreneurs’ websites portrayed their CEE courses as providing young people with opportunities to gain agency and self-confidence by learning the right contents and completing sufficient exercises. However, the limited agency that students were granted within these programmes contradicts the fact that they are individually held accountable for succeeding or failing the CEE.

Our study of edupreneurs’ websites is an initial step to show how compensating for and commodifying an educational gap feeds a flourishing PST market. This market depends on selective regulations for which the government takes full responsibility, including the power to introduce change. No matter whether political majorities advance changes to education, we consider it important for educational research to continue to critically assess changes in the entanglement between formal schooling and shadow education on local and global scales. Where our data were drawn from a local case study in Zurich, the overall issues have much wider relevance for educational policy and society. Particularly in societies with highly selective education systems, PST is seen as a requirement for students to succeed in their school careers (e.g., [

5,

8,

13,

23,

28]). To counter increasing social inequalities, schools may offer comprehensive and free-of-cost learning support [

17]; yet by this, schools are running the risk of mimicking an arms race in education. In our view, it is important to ask why societies tend to hold on to educational structures that prioritise the needs of the system over the needs of the children. Thinking about education differently would also mean starting a critical public debate if and how selective education systems can be reconciled with educational justice.