Abstract

Used in higher education for many decades, seed grants are now beginning to be applied as a strategy to advance diversity, equity and inclusion goals, including rebuilding community post-pandemic. There is little research on the effectiveness of seed grants for such communal goals. This work is innovative in two key ways. First, these seed grants focus on promoting a strong sense of community at the institution rather than promoting individual investigators and research projects. Second, engaging students and staff as principal investigators (PIs) disrupts power structures in the academy. We present a systematic analysis of seed grant project reports (n = 45) and survey data (n = 56) from two seed grant programs implemented at the same institution. A diverse set of projects was proposed and funded. Projects had a positive impact on awardees and their departments and colleges. Seed grant program activities were successful at building community among awardees and recognizing individual efforts. Most noteworthy are the career development opportunities for graduate students, postdocs and staff, which are afforded by changes to PI eligibility. We conclude that seed grant programs have the potential for organizational learning and change around community building in higher education.

1. Introduction

When it comes to inclusivity-related goals, most higher education institutional change projects focus on closing achievement gaps among undergraduates and in baccalaureate degree attainment. There are now seed grant programs with inclusivity goals at a number of institutions, but research and evaluation results of these programs have not fully emerged, and program models vary substantially. We present an analysis of the impacts on individuals and many levels of the institution, from seed grant programs to promoting community transformation, where all members can experience belonging. This article describes two key innovations in university seed grant programs: (1) application to climate and inclusivity and (2) principal investigator (PI) eligibility requirements to engage students and staff in the process.

1.1. Organizational Change and the Need to Create Belongingness for All

Literature syntheses conclude that a welcoming higher education institutional environment that promotes community and belonging is an important component of providing equitable access to students [1,2]. COVID-19-related social distancing severely eroded community and belongingness in institutions of higher education [3,4]. Recent research has underscored the importance of community and belonging for student persistence to degree attainment [5,6,7,8]. Since community is so intimately tied to the culture of the many sub-organizations within a university, successful change efforts need to engage as many as possible in the process of transforming climate and building community [9,10].

Bensimon [9] emphasizes that institutional change requires engagement and inquiry from all members of the community. Organizational learning among faculty members, advisors and administrators is required for new viewpoints to take hold and result in deep changes within higher education institutions. Specific to racial achievement gaps among undergraduates, Bensimon argues for institutions and their actors to take up an equity frame. Such a perspective could shift focus to inequities perpetuated by the institution and its faculty and staff rather than attributing differences to the qualities of the students themselves, the latter of which is a deficit perspective [9].

Similarly, Robinson [11] notes that funding efforts to improve representation have increasingly focused on changing institutions rather than changing students through extracurricular interventions. She echoes Bensimon’s call for organizational learning and building a critical mass of individuals committed to removing barriers to the success of all students. Such change efforts must emphasize learning and skill development for staff and faculty at all levels, not just the students. In short, “change is a collective responsibility” [11] (p. 46).

In this vein, the seed grant programs described in this paper were designed around two learning organization conditions [12]: (1) new ideas are developed within the institution, and (2) these ideas lead to changes in how the institution operates. Those who are affected by programs (e.g., students) can have excellent ideas about ways their institution can be improved to serve them. As such, our seed grant programs seek to provide the infrastructure to support these ideas by providing awardees with funding, administrative support and professional development. Seed grant projects also provide an opportunity to pilot new initiatives. Impactful initiatives may lead to institutional change through recommendations to improve existing programs or the continuation of piloted programs [13]. Finally, such a grant program also elevates and recognizes work that is otherwise invisible, for example, helping students with homelessness or food insecurity, mentoring students and improving campus climate for marginalized students [14].

1.2. Seed Grants

Seed grants, mini-grants and micro-grants have been used in higher education for many decades to support the broader goals of institutions, often to launch the careers of early-career faculty and jumpstart research in new directions. Far fewer seed grant programs support communal goals directly. One seed grant program funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation ADVANCE program supported inclusivity goals by promoting the research success of women faculty and postdocs [15]. Such seed grants have been successful in spurring professional advancement for awardees, policies and procedures that benefitted other faculty, and possibly, spurring increases in the number of women faculty who were promoted or tenured [15]. A seed grant program for interprofessional education in a medical school initiated innovative educational practices to integrate into degree requirements and identified champions within the organization [13]. Yet, there are few archivally documented examples of the seed grant mechanism being applied toward community building and belongingness-related goals.

An internet search reveals that some institutions offer one-year seed grants similar to the programs described in this paper. These programs may be hosted at the institution or the college level. At the institutional level, seed grant programs are or have been hosted by offices such as the Provost [16], Vice Chancellor for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) [17], institution-wide DEI offices [18,19,20] and externally-funded grants [15,21]. Based on these sites, maximum award amounts typically range from US$1000–$5000 but can be as high as $15,000. Some programs are open to anyone who wishes to apply (students, staff, faculty), while others are open to only faculty and staff. Seed grant programs at the college level are less common. The University of Michigan College of Engineering’s DEI grant program is open to faculty only, with a maximum award amount of $15,000 [22].

In sum, community is important to belongingness, equity and access to higher education. Institutional change to rebuild community post-pandemic requires engagement from people at many levels of the organization. Seed grants are a promising practice for achieving such engagement and change, but there has not yet been literature describing seed grants so focused on climate and inclusivity goals nor with expanded PI eligibility requirements to engage students and staff as leaders in community transformation.

1.3. Research Questions

This article presents an analysis of evaluation data from two seed grant programs at the same institution to answer the following research questions:

- What types of people and projects, and from what units, are attracted to apply for community transformation seed grants?

- What is the impact of community transformation seed grants on their departments, units and colleges?

- What is the impact of community transformation seed grants on awardees?

- To what extent can a community transformation seed grant program build community among awardees?

- To what extent can community transformation seed grants signal the value of community and inclusiveness at an institution?

2. Materials and Methods

The two seed grant programs are built on each other. Feedback from the first cohorts of university-level seed grants informed the design, requirements and implementation of the college-level grants program. As such, program goals and data collection methods evolved over time.

2.1. Setting 1: University-Level Seed Grant Program

The university-level seed grant program ran for three academic years (2020–2021, 2021–2022, and 2022–2023). These seed grants addressed community building and inclusive practices in a variety of ways in units across the campus. Grantees were supported through monthly online community-building workshops and an in-person community fair with an interactive poster session and reception each November following the grant period.

Proposals were no longer than two pages and included descriptions of project rationale, outcomes, impact and metrics for evaluation. A budget was also included for the $3000–$5000 grants. The call for proposals stated that projects may include piloting new ideas, testing new initiatives or data collection on issues of interest. Topics could include but were not limited to improving graduate or undergraduate education, enhancing departmental culture, hiring and recruitment, faculty/staff promotion and retention, needs assessment, collaborating with campus resources and mentorship. Projects were required to be led by a faculty member but could have outcomes geared toward faculty, staff or students. Staff and students could serve on project teams. Following evaluation by a small 2–3-person committee of the provost’s office staff, the success rate was approximately 80%. Funding came from university budgets and local collaborations with other units across campus (i.e., college deans’ budgets). Upon award, funds were transferred to the PI’s home department.

2.2. Setting 2: College-Level Seed Grant Program

The college-level seed grant program was proposed in a grant application after the first successful year of the university-level program and implemented in December 2022 based on two years of experience administering the university-level seed grants within the college. The program ran for two years, and project reports from the first cohort are presented here.

The most significant change to the seed grant program structure was in principal investigator (PI) eligibility. We realized that given the reward system for faculty and STEM faculty in particular, simply broadening eligibility for seed grants would not result in the diversity of investigators desired to transform the climate at the institution. Thus, for the college-level program, faculty were prohibited from serving as PI. Faculty could collaborate with PIs, who were staff, postdocs and students.

To provide professional development support for non-faculty PIs, the college-level seed grant program staff created and shared a number of resources. The program’s website hosted a proposal template, and the program manager presented the template in detail at a pre-proposal information session. In addition to typical details about personnel, project plans and rationale, the template required proposals to include metrics for evaluation and anticipated project outcomes and impact. Community-building among grantees was not an explicit goal for this seed grant program.

Proposals were no longer than two pages, plus a budget of $3000–$5000 and literature citations. The seed grant program manager offered seven hours of office hours where applicants could ask questions and receive feedback on proposal drafts. Applicants were also provided with the scoring rubric ahead of time to use in preparing their proposals. The call for proposals stated that projects may include piloting new ideas, testing new initiatives or data collection on issues of interest. Topics could include but were not limited to improved support of undergraduate education, departmental climate, understanding of unique needs of different populations on campus, mentoring practices and student recruitment practices. Each proposal was reviewed by two reviewers, comprising undergraduate and graduate students, staff and faculty who had previously participated in relevant efforts. The application success rate was above 60%. A variety of topics in the highest-scoring proposals emerged naturally; thus, the program manager did not need to selectively award proposals to create diversity in topics. This seed grant program was funded by a U.S. National Science Foundation grant with the goal of broadening participation in engineering. Grant funds were centrally managed by a single administrative assistant who processed reimbursements, hourly pay appointments and purchases.

2.3. Program Goals

Data were originally collected for evaluation purposes from both programs, focusing on the following program goals:

- Impact of projects on departments, units and/or the college (both seed grant programs);

- Impact on awardees (college seed grant program only);

- Community building among awardees (university seed grant program only);

- Valuing community and inclusiveness-building efforts at the university (university seed grant program only).

2.4. Data Sources and Sample Size

Three main data sources were used to evaluate the seed grant program goals:

- University program: 33 final reports (for 52 awards) from the 2020 cohort and 2 final reports (of 40 awards) for the 2021 cohort;

- University program: 11-question survey about grant background and impact. The survey was completed by 56 participants out of the 294 faculty, staff, graduate students and external partners (duplicate individuals participating in multiple projects were not removed from these totals). Surveys were completed anonymously;

- College program: 10 of 11 projects in the first cohort gave consent to use proposals, final reports and posters for document analysis.

2.5. Data Analysis

For survey results, we report the means and frequencies of responses. For awarded projects’ proposals, final reports and posters from the end-of-program poster session, we conducted document analysis. Document analysis is a qualitative analysis approach that uses a systematic procedure for reviewing or evaluating documents [23]. This approach requires examining data (the documents) to elicit meaning. First, we categorized projects into categories of focus, aligning with the suggestions in the call for proposals and adding new categories as needed to capture all project foci. Then, using final reports (both programs), proposals and posters (college program), we followed Bowen’s [23] procedure for document analysis: “(1) skimming (superficial examination), (2) reading (thorough examination), and (3) interpretation”. This iterative process involves organizing information into categories related to the research questions and combines elements of content and thematic analyses [23]. Specifically, we organized data into categories aligning with the program goals listed in Section 2.3, namely impact on individuals, impact on organizations, community-building and valuing community-building and inclusivity efforts. Within these categories, we further compared and contrasted passages from different projects to arrive at the findings reported below.

3. Results

3.1. Awardee Characteristics, Project Topics and Scope

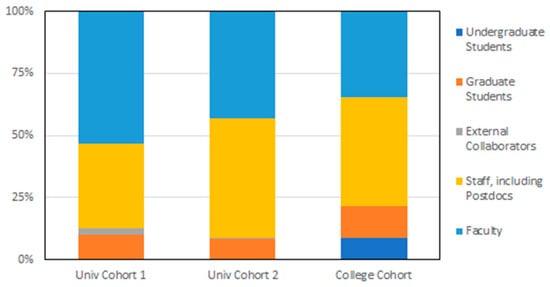

Figure 1 illustrates the increasing participation of staff and students in seed grants over time. University seed grant cohort 1 consisted of 52 projects with 160 team members, broken down as illustrated in the figure. University cohort 2 was 40 projects with 134 team members. College seed grant cohort 1 comprised 11 projects to 22 team members. Staff participation climbed from 34% to 45%, and graduate student participation went from 10% to 14%, with increasing opportunities for project leadership in the college-level seed grant program.

Figure 1.

Seed grant investigators for university cohort 1, university cohort 2 and college cohort 1. Evolving eligibility criteria reduced dominance by faculty and created opportunities for staff and students to lead community transformation projects.

Table 1 summarizes the categories represented by seed grants. Some grants were placed in multiple categories, so the totals in each column do not correspond to the number of grants. Among university grants, the most-addressed categories in 2020 were faculty development, department climate and undergraduate education. In 2021, departmental climate, undergraduate education and curriculum changes were the most addressed. College program seed grants represented a variety of approaches aligned with each seed grant project’s PIs’ lived experiences and areas of expertise. Student support programs were the most common and included a mentorship program, learning community, climate survey and recommendations report, and community-building event. Projects also impacted a range of community members in the college of engineering: six projects were department-specific, three were college-wide and one invited current community members as well as alumni. While it was a goal from the beginning to fund projects with a variety of foci and impacted populations, program staff were not expecting to receive proposals with such variety.

Table 1.

Seed grant categories.

3.2. Impact of Projects on Their Departments, Units and Colleges

Based on content analysis of proposals, reports, surveys and final posters, awardees describe the outcomes of the seed grant projects as overwhelmingly positive. In just one case, the unit described the experiment as failed but informative about what types of community-building activities may work in the future for employees of the unit.

The scope of university seed grant projects varied widely. Some final reports described multiple ongoing initiatives in a unit, while other final reports described their initiatives as complete or framed them as an information-gathering pilot for a future, larger project. Some reports differed substantially from the interim reports, indicating that the goals changed over time, perhaps to become more achievable. It should be noted that there is likely some selection bias in more successful projects submitting final reports. Only 63% of 2020 projects submitted final reports. Therefore, we can conclude that the university grants program had a generally positive impact on units across campus. The lack of a structured reporting template limited our ability to compare impacts across projects.

We learned to provide a more structured template for reporting on college program seed grant projects, as well as a strong emphasis in the program on awardees conducting their own detailed project assessments. We analyzed question two on the final reports (“What impact did your project have on [the college of engineering] community?”) as well as the projects’ posters, which were required to have a “Project Impact and Evaluation” section. Awardees created their own evaluation plans and instruments. The most common evaluation method was surveys (n = 8 projects). Surveys were drafted by seed grant team members, with the exception of one based on an existing survey. The two projects that did not use surveys either reported numbers of participants or were qualitative research projects involving interviews. Seven projects impacted a total of 147 people. One project completed a departmental climate survey, and another was a research project. It is difficult to determine how many people were impacted by these projects; however, they had 213 and 8 participants, respectively. These two projects resulted in recommendations reports for their department and the college of engineering. One project did not report its number of participants. All projects submitted final reports.

Two projects focused on undergraduate and graduate student support completed both pre- and post-program surveys for participants in their projects’ activities. Evaluation of the undergraduate mentoring program showed that participants had an increased sense of belonging in their department (from 4.7 to 5.3 out of 6) and increased “identity as an engineer” (from 5.21 to 6.86 out of 7). Evaluation of a graduate student retreat showed that afterward, students reported a greater ability to advocate for themselves, knowledge of strategies for conflict management and self-doubt, resources available at the institution, the meaning of self-empowerment, methods of self-empowerment and feelings that the university cares about supporting their needs. Neither project completed analyses to determine if these findings were statistically significant. Additional impacts from other projects include improved satisfaction as a graduate teaching assistant, an increase in sense of belonging, a likelihood to take another professional development course at the institution, increased interest in attending graduate school and providing undergraduate students with volunteer opportunities.

3.3. Impact on Awardees

The college-level grants program had an explicit goal of impact on awardees’ professional development. We evaluated the impact of participating in the seed grant program by analyzing question five on the seed grants’ final reports: “What impact did participating in the seed grant program have on you, personally, or other members of your team?” Five of the ten final reports described participation as professional development. The one undergraduate-led project described how participating in the program taught them about program management (creation, logistical challenges, timeline constraints) and “shaped me into a better leader”. One (of one) undergraduate student, one (of two) graduate students, two (of three) postdocs and one (of four) staff reported that leading a seed grant project was a professional development opportunity to teach them principal investigator (PI) skills such as writing a proposal, managing a project or research program, completing the IRB approval process, mentoring undergraduate students and conducting project evaluations. As one graduate student said,

“Participation in this project gave me my first real taste of what academia could be like. As the ‘PI’ of this project I learned, in a hands-on way, how to articulate my ideas via proposal and how to manage my own research program. This program was an incredible opportunity to grow as a researcher and is a real hallmark of my graduate education”.

One postdoc learned about the importance of interpersonal dynamics for successful inclusivity efforts and their future career, commenting, “This project helped me realize that getting interdepartmental cooperation and buy-in is quite difficult… Having the right people in place is critical to success. This has helped me grow as a future faculty member”. One staff member echoed the importance of faculty buy-in and found that their project “has encouraged further faculty participation in recruitment activities” and also shared that the project helped their department develop working relationships with minority-serving institutions in the state.

The college-level seed grant program had additional impacts on awardees’ academic and career plans. Awardees from four projects intend to publish conference or journal papers about their undergraduate recruitment or professional development projects, climate surveys and research findings. One awardee intends to submit a proposal for federal funding using preliminary data collected from their project on undergraduate student support. In the second year of the seed grant program (August 2024), awardees were invited to submit proposals that expanded upon their first year’s efforts. Three submitted proposals; all three were awarded funding. The awardee whose project was about broadening participation in professional development used the seed grant program as an opportunity to pilot a course, which they will further explore and fund through other mechanisms. Two awardees gained interest in engineering education or equity work in the college of engineering or, more broadly, in higher education.

Participating in the seed grant program also increased two awardees’ sense of connection to their department or community in the college of engineering. One postdoc felt their department-focused project “was a great way to get to know the department and the students”. One graduate student reported a “sense of belonging and community” after seeing others with a “shared interest in making [the college of engineering] community better for students”.

3.4. Community Building among Awardees

Community building among awardees was a goal of the university-level seed grant program, which we evaluated through survey data. Out of the 52 programs and 294 team members invited to complete the survey, there were 56 full responses and 3 partial responses. The 19% response rate is reasonable for an online survey, but there is likely a bias in who chose to respond. Thirty-four (59%) respondents attended most of the regular seed grantee meetings, with 22 (38%) attending a few and 2 (3.5%) attending none. Thirty-three (56%) attended the community poster session, and 26 (44%) did not attend.

The impact responses were mostly positive. Based on the survey responses, the university seed grant program assisted grantees with building a community that values inclusivity. When asked to consider their community building, grantees’ responses were positive (Q6, Table 2). They felt like they met people they would be interested in working with in the future (Q7, Table 2) and that they had meaningful conversations about DEI (Q8, Table 2). These items were among the most positive in the survey. We can conclude that seed grant community meetings and other program components are successful in building community among grantees.

Table 2.

University grant program survey responses. Response scale is 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. n = 56 to 58 responses.

3.5. Valuing Community and Inclusiveness-Building Efforts at the University

Recognizing community and inclusivity efforts was another goal of the university seed grant program. Survey responses are included in Table 2. The most positive response came when grantees were asked if they felt like they were contributing something bigger to the university, with a mean of 4.32 (strongly agree = 5; Q9, Table 2). When asked if the participants felt like their DEI efforts were valued across the university, responses were slightly less positive. Question 10 about feeling like the university values their DEI work had 11 (20%) strongly agree, 30 (54%) agree, 11 (20%) neither, 3 (5%) disagree and 1 (2%) strongly disagree responses. Question 11, asking if participating in the program increased their sense of belonging at the university, was answered 16 (29%) strongly agree, 22 (39%) agree, 16 (29%) neither, 2 (4%) disagree 0 and strongly disagree 0. These responses were the only means to fall below strongly agree (5) to agree (4), at 3.93 and 3.84, respectively (Table 2). While these responses were still largely positive, it is less realistic to expect that a seed grant program would influence how and whether employees feel their efforts are being valued overall at the institution. Nonetheless, the seed grants seem to have contributed to an increased sense of appreciation for community and inclusivity efforts on the part of the university administration. It is also difficult to decouple how the general flux with respect to the anti-DEI political climate that was emerging at the time of these surveys [24] affected the perception of the participants as to how others valued their work.

4. Discussion

This study has demonstrated the significant potential of seed grants for community transformation and professional development in higher education. The findings align with research recognizing that institutional change requires an asset-based approach, engaging faculty, staff and students at all levels of the organization [9,10]. A key innovation of the program was the inclusion of non-faculty principal investigators (PIs), which disrupted traditional power dynamics and broadened the participation of students. This inclusivity is essential for facilitating organizational change [11].

Building institutional capacity for change hinges on involving a diverse array of stakeholders, including students, staff and non-faculty researchers [12]. For an institution to operate as a true learning organization, the ideas generated for change must emerge internally, contributing to lasting shifts in how the institution functions [11,12]. The success of the college-level seed grant program, which prohibited faculty from serving as PIs, highlights the value of empowering non-traditional leaders in efforts toward institutional transformation.

4.1. Community Building

One of the primary goals of the seed grant programs was to strengthen the university’s research community with a particular focus on inclusivity. Our findings support Robinson’s [11] call for institutional learning, where the focus shifts from changing students to transforming institutional structures. The seed grant projects prioritized mentorship, departmental climate improvement and student support while recognizing and rewarding work that might have remained invisible within the institution [14]. As an example, an undergraduate mentoring program funded by a seed grant reported a significant increase in participants’ feelings of belonging and a stronger sense of identity as engineers, illustrating the positive influence of the seed grants on community engagement.

The involvement of staff and graduate students in these initiatives also underscores the importance of diverse contributors in building inclusive communities, helping to mend the fragmentation exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic [3,4]. However, achieving deep institutional change is a gradual process that requires sustained effort. Not all seed grant projects yielded immediate or measurable results, particularly those centered on community building. Some initiatives encountered logistical and institutional challenges, while others experienced changes in scope due to unforeseen obstacles.

4.2. Professional Development

Beyond their broader focus on programming, the seed grants were pivotal in providing professional development opportunities for participants, particularly students and staff. These opportunities empowered them to lead initiatives and fostered a sense of community rooted in inclusivity.

Graduate students and postdoctoral fellows reported that leading seed grant projects significantly enhanced their skills in project management, research design and navigating institutional systems, such as securing Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. One postdoctoral participant reflected on the complexities of obtaining interdepartmental cooperation and buy-in, noting that these experiences would inform their future academic career.

These outcomes of seed grants focused on building institutional capacity through organizational learning rather than exclusively targeting individual student interventions [11]. By involving non-faculty PIs, the seed grants have expanded professional growth and leadership opportunities, addressing a crucial gap in the development of staff and students. Additionally, some participants have begun to evolve their seed grant projects into larger, institution-wide initiatives, further showcasing the program’s ability to inspire and support long-term institutional change.

4.3. Challenges and Looking Ahead

Despite the program’s successes, the evolving political climate surrounding DEI in higher education [24] may have influenced participants’ perceptions of institutional support. While most respondents reported positive experiences and believed their work contributed to the institution’s broader goals, a few expressed uncertainty about whether their efforts were genuinely valued. This suggests that external political pressures may impact the perceived success of DEI initiatives within institutions. This is a particular challenge to DEI leaders whose positions are being eliminated to comply with anti-DEI legislation. The current dynamic climate for DEI in higher education [24] raises important questions about how and whether community-focused efforts can be sustained, both formally and informally, at public institutions in states where explicit focus on inclusivity is prohibited.

The implicit change strategy embedded in these seed grant programs was a grassroots approach with elements of both social cognition (i.e., organizational learning) and cultural change theories as classified by Kezar [10]. While the focus of program activities was to support investigators in executing their own chosen projects and to maintain motivation through recognition, the seed grant programs unleashed a great deal of energy among staff, students and faculty. Next-generation community and inclusivity seed grant programs might more explicitly address harnessing this energy toward institutional goals and priorities. For example, other seed grant mechanisms, such as those supporting faculty research, are frequently aligned to strategic priorities and favor projects that advance those priorities. One problem is that while diversity targets, e.g., representation among students, may be specific, how to get there may not be as clearly laid out in a strategic plan. After completing their own one-year seed grant projects, some grantees may be better motivated to focus on identifying and working on systemic issues. It is likely that some leadership and facilitation are required to ensure productive dialog and action. Nonetheless, the year-long process of selecting, supporting and reviewing reports from seed grantees may be a useful way for administrators to identify which actors at the university have developed the skills, knowledge and persistence to do the difficult work of deep institutional change.

4.4. Study Limitations

Response rates were reasonable for online surveys but low for a grant program for which recipients might be concerned about their eligibility to receive additional funds in the future. In this case, low response rates were likely indicative of some bias in that less complete or less successful projects and participants did not submit.

5. Implications

Based on the evidence collected and analyzed, we conclude that seed grant programs focused on inclusive community transformation can be successful in (1) a variety of units and levels across a campus, (2) providing professional development opportunities for staff and students, (3) community building among grantees and (4) demonstrating that the university values these efforts. Early iterations of the seed grant programs informed additional scaffolding provided to PIs and, importantly, a change to eligibility criteria that prevented faculty from dominating initiatives.

This study has identified several benefits of structuring a program in this way. First, by calling for and supporting ideas for community building and inclusivity that are generated from the communities that they impact, the program benefits from the awardees having knowledge of on-the-ground needs and what might be likely to work given participants’ time constraints and interests. As previously mentioned, this also led to a wide variety of project topics. Finally, rather than relying on core staff for all of the program ideas and implementation, such programs truly seeded a more diverse slate of initiatives than a smaller team of individuals could have created on their own.

The lessons learned from running these seed grant programs are relevant for those wishing to develop or improve similar programs at their own institutions. We recommend:

- Providing awardees with information about how to conduct program evaluations: Seed grant program participation is an opportunity for awardees to learn about how to conduct program evaluations on a project of interest. Also, as many awardees planned to continue their projects in some capacity, their future efforts would benefit from more robust evaluations. Program managers would benefit from detailed evaluation data when reporting back to funders (e.g., NSF, institutional leaders, private donors). In year two of the college program, we hosted a mini-workshop on program evaluation, and improved project evaluation conducted by awardees will aid in our own program evaluation;

- Developing infrastructure for administrative support prior to launching the program: For the centrally managed seed grant funds, clearer processes and timelines for spending and reimbursement were needed. We worked with our institution’s post-award research administrators to develop clear guidelines about what program expenses were allowed or disallowed on the external funding grant. We also now require all projects doing K-12 outreach to meet with the college of engineering’s outreach program coordinator;

- Requiring letters of support from external partners: One challenge and cause for delay in Year 1 projects was finding that working with partners outside of the institution can be challenging and take longer than anticipated. To mitigate this, proposals were required to submit letters of support if working with external partners (e.g., K-12 schools);

- Offering office hours: Office hours were very popular during the proposal submission phase of the project and contributed to awardees’ success, with many successful proposals having been submitted by people who attended office hours. For the majority of applicants for college-level seed grants (undergraduate students, graduate students, staff), this was the first time that they had submitted a proposal. Office hours were advertised as an opportunity to get questions answered, receive feedback on draft proposals and listen to others’ questions;

- Sharing reviewer comments: Reviewers had valuable feedback for applicants. For awarded projects, reviewers’ comments offered advice or ideas; for unawarded projects, they offered advice on how to improve the proposals for resubmission the following year;

- Building community among awardees: Building community among awardees was not the main goal of the college-level seed grants, but awardees suggested adding ways for future awardees to connect with each other and discuss their projects. Connecting grantees appears to be an important component of supporting inclusivity efforts.

6. Conclusions

The seed grant programs described in this paper have deeper implications for building inclusive communities in higher education. While it is understood that not all seeded projects will ultimately take root for a variety of reasons, by providing a small initial investment that engages “people on the ground”, this approach can identify potential initiatives that are ripe for growth and identify what additional investments in terms of time, monetary resources and infrastructure are necessary to see them bear fruit for the long term. Further, even for projects that do not ultimately grow into something larger, distilling and remembering lessons from ideas worth trying can provide insights into the creation and seeding of different initiatives in the same vein. Finally, such awards identify and recognize champions for ongoing efforts at the institution. We conclude that seed grants may be a change initiative with a relatively high return on investment, particularly when impacts on climate and individual investigators are considered.

Author Contributions

Project administration, G.C.F., D.W., L.C. and C.J.; methodology, G.C.F., M.B. and S.A.C.; formal analysis, S.A.C. and G.C.F.; investigation, S.A.C. and G.C.F.; resources, L.C. and C.J.; writing—original draft preparation, G.C.F., S.A.C. and M.B.; writing—review and editing, D.W., A.B., L.C. and C.J.; supervision, M.B. and A.B.; funding acquisition, C.J., L.C., G.C.F., A.B. and M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by U.S. National Science Foundation grant numbers 2217741 and 2347045.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Texas at Austin (00002550 was approved on 30 March 2022 and 00002998 on 10 June 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy concerns of the participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Palid, O.; Cashdollar, S.; Deangelo, S.; Chu, C.; Bates, M. Inclusion in practice: A systematic review of diversity-focused STEM programming in the United States. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2023, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterer, E.R.; Froyd, J.E.; Borrego, M.; Martin, J.P.; Foster, M. Factors influencing the academic success of Latinx students matriculating at 2-year and transferring to 4-year US institutions—Implications for STEM majors: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2020, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, M.; Linden-Carmichael, A.; Lanza, S. College students’ sense of belonging and mental health amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 70, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tice, D.; Baumeister, R.; Crawford, J.; Allen, K.-A.; Percy, A. Student belongingness in higher education: Lessons for Professors from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2021, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, G.M.; Cohen, G.L. A question of belonging: Race, social fit, and achievement. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, G.M.; Cohen, G.L. A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science 2011, 331, 1447–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedler, M.L.; Willis, R.; Nieuwoudt, J.E. A sense of belonging at university: Student retention, motivation and enjoyment. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2022, 46, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Museus, S.D.; Chang, T.-H. The impact of campus environments on sense of belonging for first-generation college students. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2021, 62, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensimon, E.M. Closing the achievement gap in higher education: An organizational learning perspective. New Dir. High. Educ. 2005, 131, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kezar, A. How Colleges Change: Understanding, Leading, and Enacting Change; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, T.N. The myths and misconceptions of change for STEM reform: From fixing students to fixing institutions. New Dir. High. Educ. 2022, 2022, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dill, D.D. Academic accountability and university adaptation: The architecture of an academic learning organization. High. Educ. 1999, 38, 127–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, R.; Moote, R.; Krolick, K.A.; Farokhi, M.R.; Ford, L.A.; Quinene, M.; Ratcliffe, T.A.; Rockne, M.; Zorek, J.A. A university-wide seed grant program accelerates interprofessional education through faculty and staff engagement. J. Interprofessional Care 2024, 38, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.M.; Kee, C. The invisible labor of diversity educators in higher education. SoJo J. 2021, 7, 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, M.; Mason, S.; Marchetti, C.; Dell, B.; Litzler, E.; Valentine, M. Reimagining Seed Grants for the 21st Century: Individual and Institutional Impacts of a Mini-Grants Program. Adv. J. 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Texas at Austin. Seed Grants for Actions that promote Community Transformation (ACT). Available online: https://provost.utexas.edu/initiatives/past-initiatives/seed-grants-for-actions-that-promote-community-transformation-act/ (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- University of Illinois. Broadening Inclusion Grant. Available online: https://diversity.illinois.edu/diversity campus-culture/broadening-inclusion-grant/ (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Michigan State University. Creating Inclusive Excellence Grants. Available online: https://inclusion.msu.edu/research/creating-inclusive-excellence-grants/index.html (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Loyola University Chicago. READI Innovation Fund. 2024. Available online: https://www.luc.edu/diversityandinclusion/missioninaction/readiinnovationfund/ (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Farmingdale State College. DEI Innovation Grant Program. Available online: https://www.farmingdale.edu/equity-diversity/2023-10-23-dei-innovation-grant-program.shtml (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Dell, E.; Mason, S.; Bailey, M.; Marchetti, C.; Valentine, M. Mirroring and Modeling an External Award Process: Structuring a Career Development Grants Program for Women at a Striving University. In Proceedings of the 2022 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 26–29 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- University of Michigan Engineering. DEI Faculty Grant. Available online: https://culture.engin.umich.edu/diversity equity-and-inclusion-dei-faculty-grant/ (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Bowen, G.A. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posselt, J.R. From Innovations to Isomorphism in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Efforts: Opportunities and Cautions for Higher Education. Change Mag. High. Learn. 2023, 55, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).