Life Skills in Compulsory Education: A Systematic Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Life Skills as a Complex Concept

1.2. Life Skills as an Individual and Social Phenomenon

1.3. Objectives

- What characterizes the empirical research on life skills in compulsory education?

- What are the purposes, explicit focus areas, methods, designs, and samples of the included studies?

- How are life skills defined in educational research?

- What specific definitions of life skills are used in educational research?

- Which perspectives of collectivism and individualism are visible in the definitions of life skills?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Methodological Approach

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2.1. Population

2.2.2. Concept

2.2.3. Context

2.2.4. Types of Evidence Sources

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Data Management and Study Selection Process

2.5. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

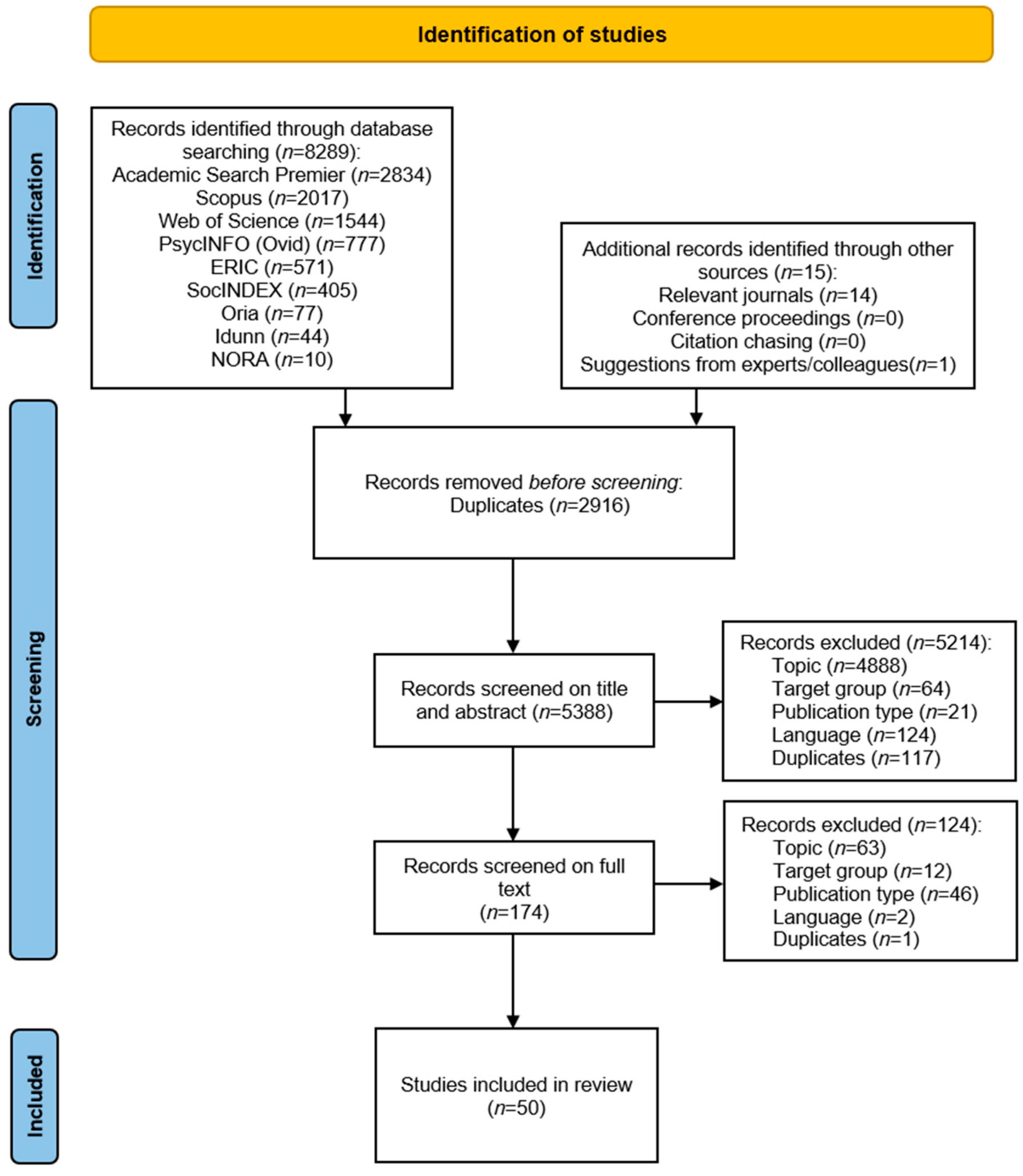

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

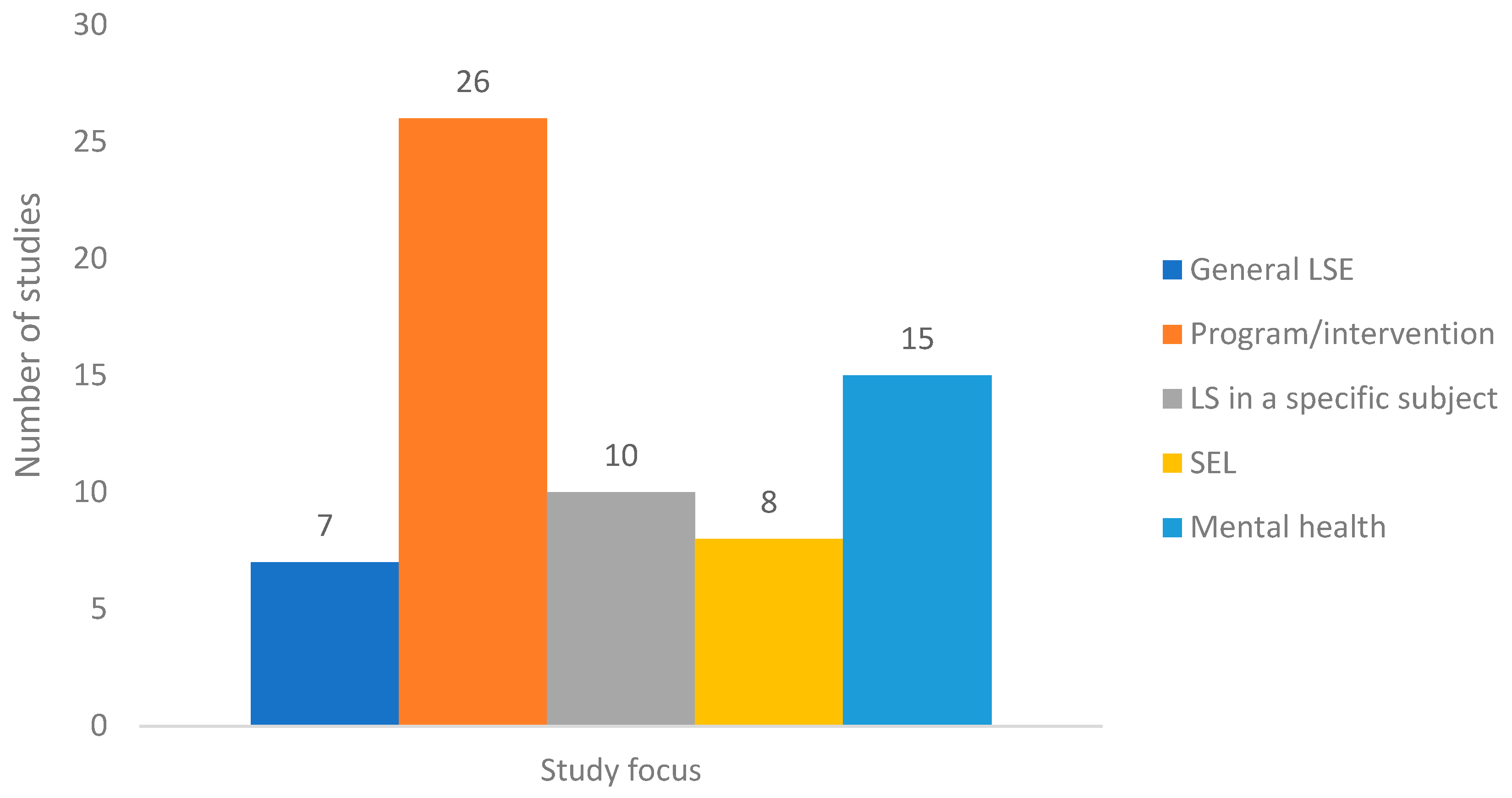

3.1.1. Study Purposes and Explicit Focus Areas

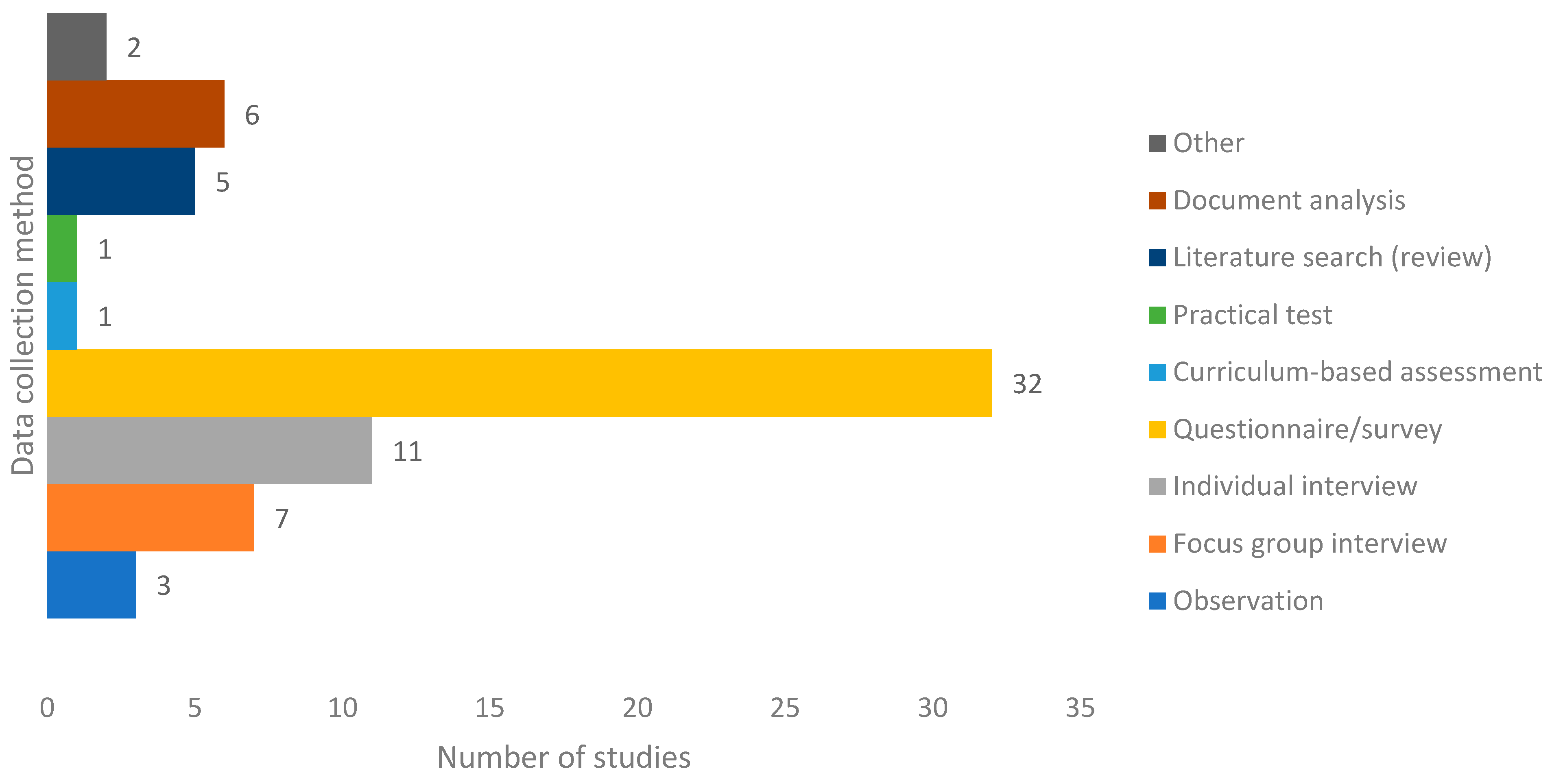

3.1.2. Methods Used in the Studies

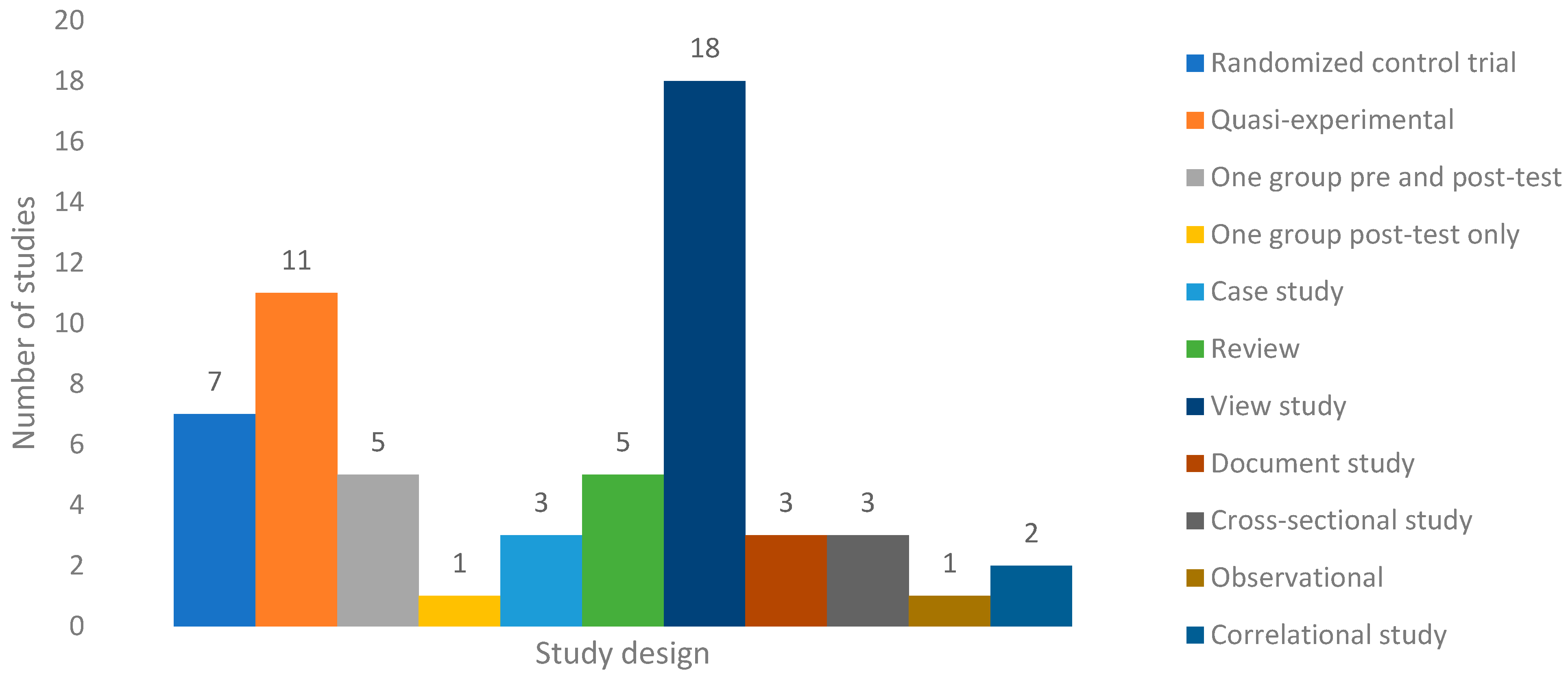

3.1.3. Study Designs

3.1.4. The Study Subjects

3.2. Thematic Analysis of Definitions of Life Skills

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of Main Findings

4.2. Characteristics of the Studies

4.2.1. Contextual Differences

4.2.2. Link between the Studies’ Focus Area, Purpose, and Methods

4.2.3. The Role of Age in Life Skills Education

4.3. Definitions of Life Skills

4.3.1. Lack of Definitions

4.3.2. Diverse, but Similar Definitions

4.3.3. Broad-Based Approach

4.3.4. A Call for a Clear and Updated Definition

4.3.5. Individualistic Perspectives

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions and Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Dupuy, K.; Bezu, S.; Knudsen, A.; Halvorsen, S.; Kwauk, C.; Braga, A.; Kim, H. Life Skills in Non-Formal Contexts for Adolescent Girls in Developing Countries. CMI Report Number 5; Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED586329.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Life Skills Education for Children and Adolescents in School, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/59117/WHO_MNH_PSF_93.7B_Rev.1.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- UNICEF. Comprehensive Life Skills Framework; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/india/media/2571/file/Comprehensive-lifeskills-framework.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- UNICEF. Global Framework on Transferable Skills; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/media/64751/file/Global-framework-on-transferable-skills-2019.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Furberg, A.; Rødnes, K.A.; Silseth, K.; Arnseth, H.C.; Kvamme, O.A.; Lund, A.; Sæther, E.; Vasbø, K.; Ernstsen, S.; Fundingsrud, M.W.; et al. Fagfornyelsen i Møte med Klasseromspraksiser: Læreres Planlegging og Gjennomføring av Undervisning om Tverrfaglige Tema [Subject Innovation in the Face of Classroom Practices: Teachers’ Planning and Implementation of Teaching on Interdisciplinary Topics]; University of Oslo: Oslo, Norway, 2023; Available online: https://www.uv.uio.no/forskning/prosjekter/fagfornyelsen-evaluering/publikasjoner/eva2020---rapport-6.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Nasheeda, A.; Abdullah, H.B.; Krauss, S.E.; Ahmed, N.B. A narrative systematic review of life skills education: Effectiveness, research gaps and priorities. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2019, 24, 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, M.; Kapur, S. Facets of life skills education—A systematic review. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2022, 31, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff, E.; Keller, R. Age-Specific Life Skills Education in School: A Systematic Review. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 660878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Global Evaluation of Life Skills Education Programmes; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.edu-links.org/sites/default/files/media/file/GLSEE_Booklet_Web.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Botvin, G.J.; Griffin, K.W. School-based programmes to prevent alcohol, tobacco and other drug use. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2007, 19, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botvin, G.J. The Life Skills Training Program as a Health Promotion Strategy: Theoretical Issues and Empirical Findings. Spec. Serv. Sch. 1985, 1, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education and Research. Core curriculum—Values and Principles for Primary and Secondary Education. 2017. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/53d21ea2bc3a4202b86b83cfe82da93e/core-curriculum.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Norwegian Children and Youth Council. Livsmestring i Skolen—For Flere små og Store Seire i Hverdagen [Life Skills at School—For More Small and Big Victories in Everyday Life]; Norwegian Children and Youth Council: Oslo, Norway, 2017; Available online: https://www.lnu.no/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/lis-sluttrapport-1.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Madsen, O.J. Livsmestring på Timeplanen: Rett Medisin for Elevene? [Coping with Life on the Schedule: The Right Medicine for Students?]; Spartacus: San Simeon, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brevik, L.M.; Gudmundsdottir, G.B.; Barreng, R.L.S.; Dodou, K.; Doetjes, G.; Evertsen, I.; Goldschmidt-Gjerløw, B.; Hartvigsen, K.M.; Hatlevik, O.E.; Isaksen, A.R.; et al. Å Mestre Livet i 8. Klasse. Perspektiver på Livsmestring i Klasserommet i sju fag. [Mastering Life in 8th Grade. Perspectives on Life Skills in the Classroom in Seven Subjects]; University of Oslo: Oslo, Norway, 2023; Available online: https://www.uv.uio.no/ils/forskning/prosjekter/educate/rapporter/educate_rapport-2_2023.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Straum, O.K. Klafkis kategoriale danningsteori og didaktikk: En nærmere analyse av Klafkis syn på danning som prosess med vekt på det fundamentale erfaringslag. [Klafki’s categorical Bildung theory and didactics: A closer analysis of Klafki’s view of Bildung as a process with emphasis on the fundamental layer of experience]. In Kategorial Danning og bruk av IKT i Undervisning [Categorical Bildung and Use of ICT in Teaching]; Fuglseth, K., Ed.; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 2018; pp. 30–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torjussen, L.P.S. Danning, dialektikk, dialog—Skjervheims og Hellesnes’ pedagogiske danningsfilosofi [Bildung, dialectics, dialogue—Skjervheims and Hellesnes’ educational philosophy of Bildung]. In Dannelse: Introduksjon til et Ullent Pedagogisk Landskap [Bildung: Introduction to a Vague Educational Landscape]; Steinsholt, K., Dobson, S., Eds.; Tapir Akademiske Forlag: Trondheim, Norway, 2011; pp. 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Breivega, K.M.R.; Rangnes, T.; Werler, T.C. Demokratisk danning i skole og undervisning [Democratic Bildung in school and teaching]. In Demokratisk Danning i Skolen: Tverrfaglige Empiriske Studier [Democratic Bildung in School: Interdisciplinary Empirical Studies]; Breivega, K.M.R., Rangnes, T.E., Eds.; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 2019; pp. 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohr, H. Kategorial danning og kritisk-konstruktiv didaktikk—Den didaktiske tilnærmingen hos Wolfgang Klafki [Categorical Bildung and critical-constructive didactics—The didactic approach of Wolfgang Klafki]. In Dannelse: Introduksjon til et Ullent Pedagogisk Landskap [Bildung: Introduction to a Vague Educational Landscape]; Steinsholt, K., Dobson, S., Eds.; Tapir Akademiske Forlag: Trondheim, Norway, 2011; pp. 163–175. [Google Scholar]

- Danielsen, A.G. Lærerens Arbeid med Livsmestring [The Teacher’s Work with Life Skills]; Fagbokforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ecclestone, K.; Hayes, D. The Dangerous Rise of Therapeutic Education; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, O.J. Life Skills and Adolescent Mental Health: Can Kids Be Taught to Master Life? Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Skarpenes, O. De unges problem: Individualisering og kvantifiseringskultur i skolen [The young people’s problem: Individualization and quantification culture in school]. Nytt Nor. Tidsskr. 2021, 38, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehring, D. The Routledge International Handbook of Global Therapeutic Cultures; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman, W.H., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Uthus, M. Presentasjonspresset—Et individuelt eller kollektivt ansvar? [Presentation pressure—An individual or collective responsibility?]. In Perspektiver på Livsmestring i Skolen [Perspectives on Life Skills in School], 2nd ed.; Fikse, C., Myskja, A., Eds.; Cappelen Damm Akademisk: Oslo, Norway, 2021; pp. 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ringereide, K.E.; Thorkildsen, S.L. Folkehelse og Livsmestring: Tanker, Følelser og Relasjoner [Health and Life Skills: Thoughts, Feelings, and Relationships]; Pedlex: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Darlington-Bernard, A.; Salque, C.; Masson, J.; Darlington, E.; Carvalho, G.S.; Carrouel, F. Defining Life Skills in health promotion at school: A scoping review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1296609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowling, J.; Jason, K.; Krinner, L.M.; Vercruysse, C.M.C.; Reichard, G. Definition and operationalization of resilience in qualitative health literature: A scoping review. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2022, 25, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2023. 2023. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1787/e13bef63-en (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Campbell, F.; Tricco, A.C.; Munn, Z.; Pollock, D.; Saran, A.; Sutton, A.; White, H.; Khalil, H. Mapping reviews, scoping reviews, and evidence and gap maps (EGMs): The same but different—The “Big Picture” review family. Syst. Rev. 2023, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMS Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munthe, E.; Bergene, A.C.; Braak D t Furenes, M.I.; Gilje, T.M.; Keles, S.; Ruud, E.; Wollscheid, S. Systematisk kunnskapsoppsummering utdanningssektoren [Systematic review of the education sector]. Nor. Pedagog. Tidskr. 2022, 106, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2021, 19, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, D.; Sunardi, S.; Gunarhadi, G.; Yusufi, M. Reviewing the Life Skills Activity Program for Children with Special Needs during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cypriot J. Educ. Sci. 2021, 16, 3240–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanious, R. A scoping review of life skills development and transfer in emerging adults. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, L.; Black-Hawkins, K.; Rouse, M. Achievement and Inclusion in Schools, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeie, G.; Fandrem, H.; Ohna, S.E. Hvordan Arbeide med Elevmangfold? Flerfaglige Perspektiver på Inkludering [How to Work with Student Diversity? Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Inclusion]; Fagbokforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, J.D.; McMullen, N. Evaluation of a teacher-led, life-skills intervention for secondary school students in Uganda. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 217, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormanci, Ü.; Kaçar, S.; Çepni, S. Investigating the Acquisitions in the Science Teaching Program in Terms of Life Skills. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 2022, 8, 70–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanta, P.; Deuri, S.P.; Sobhana, H. Importance of Life Skills Education among Adolescents. Indian J. Posit. Psychol. 2021, 12, 403–406. [Google Scholar]

- Aldenmyr, S.I. Handling challenge and becoming a teacher: An analysis of teachers’ narration about life competence education. Teach. Teach. 2013, 19, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulluhan, N.U. Social Problem-Solving Activities in The Life Skills Course: Do Primary School Students Have Difficulty Solving Daily Life Problems? Egit. Bilim-Educ. Sci. 2021, 46, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, P.; Karmalkar, S. Effect of life skills training program on psychological well-being of rural adolescents. J. Indian Acad. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 44, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Erduran Avci, D.; Kamer, D. Views of Teachers Regarding the Life Skills Provided in Science Curriculum. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2018, 77, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, N.J.; Tripathi, S. Life skills to be developed for students at the school level. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2023, 37, 1425–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemian, A.; Kumar, G.V. Enhancement of emotional empathy through life skills training among adolescents students—A comparative study. J. Psychosoc. Res. 2017, 12, 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Gim, N.G. Development of Life Skills Program for Primary School Students: Focus on Entry Programming. Computers 2021, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klomsten, A.T.; Uthus, M. En sakte forvandling. En kvalitativ studie av elevers erfaringer med å lære om psykisk helse i skolen [A slow transformation. A qualitative study of pupils’ experiences of learning about mental health in school]. Nord. J. Educ. Pract. 2020, 14, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, S.; Pereira, B.; Khandeparkar, P. Acceptability and feasibility of the Heartfulness Way: A social-emotional learning program for school-going adolescents in India. Indian J. Psychiatry 2022, 64, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemian, A.; Venkatesh, G.K. Evaluate the effectiveness of life skills training on development of autonomy in adolescent students: A comparative study. Indian J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 8, 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, M.; Njue, R.; Njue, J. Life skills training module in an Indian context: Effects and applications on youth. IAHRW Int. J. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2019, 7, 1193–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Hoy, W.K.; Adams, C.M. Quantitative Research in Education: A Primer; Sage Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Restad, F.; Mølstad, C.E. Social and emotional skills in curriculum reform: A red line for measurability? J. Curric. Stud. 2021, 53, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L.D. Age of Opportunity: Lessons from the New Science of Adolescence; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh-Lam, A.C.; Tran, T.H.; Tran, V.H.; Ly, M.T.; Tran, V.T. Life Skills Education from the Perspectives of Vietnamese Teachers and Educators. Int. J. Educ. Sci. 2020, 29, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-J.; Wu, W.-C.; Chang, H.-C.; Chen, H.-J.; Lin, W.-S.; Feng, J.Y.; Lee, T.S.-H. Effectiveness of a school-based life skills program on emotional regulation and depression among elementary school students: A randomized study. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Norwegian Reports. The School of the Future. Renewal of subjects and competences (2015: 8). Ministry of Education and Research. 2015. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/da148fec8c4a4ab88daa8b677a700292/en-gb/pdfs/nou201520150008000engpdfs.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social Learning Theory; Englewood Cliffs Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Students aged 5–16. | Children younger than 5 years old and students older than 16 years old. |

| Teachers teaching students between the ages of 5 and 16. | School staff members other than teachers or external professionals. | |

| Main concept: Life skills | Life skills within the areas of health, lifestyle, morals and values, identity, and social and emotional learning. | Life skills as basic skills. |

| Life skills with a main focus on diseases, disorders, reproductive health, sports, substance use, and violence. | ||

| Other concepts: Inclusion Diversity | Inclusion in terms of high-quality educational opportunity for everyone. | Inclusion in terms of children with special needs. |

| Diversity related to students’ backgrounds, values, interests, and aims. | Diversity in terms of a main focus on vulnerable groups (e.g., at-risk students, institutionalized children, and minority groups). | |

| Context | Compulsory education setting. | Non-compulsory education setting, such as early childhood education, upper secondary education, and higher education, outside of an education setting. |

| Design of study | Empirical studies. | Non-empirical studies, such as theoretical or conceptual papers without data. |

| Language | English and Norwegian. | Languages other than English and Norwegian. |

| Publication year | 2013–2023. | Publication date before 2013 and after 2023. |

| Publication type | Scientific peer-reviewed articles. | Publication types other than scientific peer-reviewed articles. |

| Age (Years) | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | >16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of studies | 2 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 18 | 19 | 22 | 23 | 15 | 11 |

| Definitions (n = 32) | Examples |

|---|---|

| WHO definition (n = 14) | “Life skills are abilities for adaptive and positive behavior, that enable individuals to deal effectively with the demands and challenges of everyday life.” [2] (p. 1) |

| Variations of WHO definition (n = 5) | “Life skills are the ones that are among the 21st-century skills and help us cope with daily life problems effectively.” [50] (p. 2) |

| UNICEF (n = 3) | “Life skills refer to a large group of psycho-social and inter-personal skills that can help people make informed decisions, communicate effectively and develop coping and self-management skills that may help them lead a healthy and productive life.” [51] (p. 1426) |

| Other sources (n = 4) | “Life skills are all of the vital skills that help people to deal with the difficulties that faced in their life and guide them in solving problems.” [45] (p. 71) |

| Own definition (n = 6) | “Life skills are essentially those abilities that help to promote mental well-being and competence in people as they face the realities of life.” [52] (p. 280) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hvalby, L.; Guldbrandsen, A.; Fandrem, H. Life Skills in Compulsory Education: A Systematic Scoping Review. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101112

Hvalby L, Guldbrandsen A, Fandrem H. Life Skills in Compulsory Education: A Systematic Scoping Review. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(10):1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101112

Chicago/Turabian StyleHvalby, Lone, Astrid Guldbrandsen, and Hildegunn Fandrem. 2024. "Life Skills in Compulsory Education: A Systematic Scoping Review" Education Sciences 14, no. 10: 1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101112

APA StyleHvalby, L., Guldbrandsen, A., & Fandrem, H. (2024). Life Skills in Compulsory Education: A Systematic Scoping Review. Education Sciences, 14(10), 1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101112